Abstract

Introduction

With the lowest life expectancy in the Balkans, underlying causes of morbidity in Kosovo remain unclear due to limited epidemiological evidence. The goal of this cohort is to contribute epidemiological evidence for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases such as depression, hypertension, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease in Kosovo as the basis for policy and decision-making, with a spotlight on the relationships between non-experimental primary healthcare (PHC) interventions and lifestyle changes as well as between depression and the course of blood pressure.

Methods and analysis

PHC users aged 40 years and above were recruited consecutively between March and October 2019 from 12 main family medicine centres across Kosovo. The data collected through interviews and health examinations included: sociodemographic characteristics, social and environmental factors, comorbidities, health system, lifestyle, psychological factors and clinical attributes (blood pressure, height, weight, waist/hip/neck circumferences, peak expiratory flow and HbA1c measurements). Cohort data were collected annually in two phases, approximately 6 months apart, with an expected total follow-up time of 5 years.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approvals were obtained from the Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (Ref. 2018-00994) and the Kosovo Doctors Chamber (Ref. 11/2019). Cohort results will provide novel epidemiological evidence on non-communicable diseases in Kosovo, which will be published in scientific journals. The study will also examine the health needs of the people of Kosovo and provide evidence for health sector decision-makers to improve service responsiveness, which will be shared with stakeholders through reports and presentations.

Keywords: epidemiology, hypertension, depression & mood disorders, mental health, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

As the first prospective cohort covering different areas of Kosovo, the study will provide important evidence on the course of non-communicable diseases in a country with limited epidemiological evidence.

The longitudinal study design will allow us to observe changes in non-communicable diseases and their determinants over time in individuals and analyse the temporal sequence of changes, thus providing stronger evidence in investigating causal relationships.

Study results can be immediately applied in designing or adapting existing targeted behaviour change interventions by healthcare stakeholders.

This study is not population based due to the recruitment scheme in primary healthcare facilities, which limits its generalisability and may overestimate the prevalence of health conditions; however, healthy persons are included in the study because primary healthcare patients visit centres for an array of conditions including general check-ups.

Introduction

Burden of non-communicable diseases in Kosovo

The burden of disease in the Balkan region falls heaviest on Kosovo, suggested by a life expectancy of 72 years,1 which is lower than neighbouring countries such as Albania (78 years), Montenegro (77 years), Macedonia (76 years) and Serbia (76 years).1 It is a challenge, however, to get a better understanding of the main culprits of Kosovo’s disease burden due in part to limited epidemiological evidence given the country’s health information system is still in its initial developmental phase.2

Although it is well known that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the greatest contributor to health loss in the world, accounting for 61% (or 1.5 billion) of disability-adjusted life years (DALY), only a few estimates on NCDs in Kosovo are available. A national population-based study conducted in 2010 in Kosovo of adults over the age of 65 (n=1890) indicated that the most common self-reported NCDs were cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), with a prevalence of 63%, followed by stomach and liver disease (21%), then diabetes mellitus (DM; 18%).3

CVDs are a major health concern globally, accounting for 353 million DALYs (14.8% of all DALYs globally), over 471 million prevalent cases and 17.6 million deaths annually.4 The situation is dire in the Balkans, where the burden of CVDs is nearly double that of the global prevalence (27.7% of all DALYs for the Balkans). CVDs include coronary artery disease, cardiomyopathy, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, rheumatic heart disease, arrhythmias and endo/myocarditis. Acute CVDs events include myocardial infarctions and strokes. The Kosovo Agency of Statistics reports that CVDs were responsible for 57.9% of deaths in 2012; 18% of these occurring under the age of 60.5

Although CVDs are the principal causes of death worldwide, mental disorders are now among the leading causes of disability.4 Among mental disorders, depression is the most common with over 300 million prevalent cases worldwide (4.4% global prevalence).6 Depression results from a complex interaction of social, psychological and biological factors and is characterised by persistent sadness, loss of interest in activities a person normally enjoys and inability to carry out daily activities. People who have gone through adverse life events (unemployment, bereavement, psychological trauma) are more likely to develop depression as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD differs from depression in that the person must have experienced a traumatic event and experiences intense, disturbing thoughts and feelings related to their trauma that last long after the event has ended.

Depression and PTSD in Kosovo have been studied more extensively in the past two decades as a result of the scientific interest to study psychological effects following the war in the late 1990s. One nationally representative study (n=1161) of persons aged 15 years or older found that 41.7% had moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms and 41.6% had severe anxiety, measured by the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL).7 PTSD was present in 22% of respondents, measured by the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, and was predictive of suicidal ideation which was measured with a suicidal ideation index created using items from the General Health Questionnaire and HSCL.7 Other studies, which focused on specific regions of the country or specific subgroups, found a prevalence of depression which ranged from 29.7% to 66.5%.8–11 It is clear that depression is common in Kosovo, far exceeding the global average. Some interpret the high rates of depression as an aftermath to the stressful conditions following the war.12

In summary, CVD and depression are among the NCDs which cause the greatest burden to global health and may be important starting points for NCDs research in Kosovo.

NCD prevention and control in Kosovo

Primary healthcare (PHC) plays a key role in the prevention and control of CVDs and other NCDs.13 Primary prevention includes interventions which avert the occurrence of disease, whereas secondary prevention includes interventions which stop or slow the progression of disease once it has started.14 Many PHC interventions aim to reduce common risk factors of NCDs, such as smoking, physical inactivity and poor diet, in both healthy people and patients with NCDs. In Kosovo, the PHC system is divided into three tiers: each municipality has one main family medicine centre (MFMC), several family medicine centres (FMC) and several family medicine ambulantas (FMA). MFMCs, which formed the basis for the recruitment of the study participants, are the largest facilities at the highest level of PHC, which offer more services, staff and medical equipment and therefore have a higher patient flow compared with the second level FMCs and third level FMAs.

The Accessible Quality Healthcare (AQH) implementation project, which is funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and led by the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), started in 2016 and is now one of the prominent projects in Kosovo working within the PHC system. The AQH project has been devoted to working with local stakeholders to improve the quality of PHC in the public health sector through a health system strengthening approach, with a focus on the prevention of NCDs. The three project outcomes are as follows: (1) PHC providers deliver quality services that respond better to communities’ needs, (2) health managers improve their performance in guiding service delivery towards continuous quality improvement, and (3) the population improves its health literacy and is empowered to demand the right to quality services and better access to care.

Health systems strengthening interventions implemented by the AQH project in Kosovo are broad and complex. One of the AQH interventions for improvement of PHC services is the implementation of service packages (SPs). This intervention aims to improve the quality of care by setting standards that should be provided at PHC facilities, based on the WHO ‘Packages of Essential Non-Communicable Disease (PEN) Protocols,’15 which have been adapted to the Kosovo context by national experts. The SPs ensure a continuum of care with the family physician in a gatekeeper role, where patients who are at risk of developing diabetes or hypertension, or those who have already been diagnosed are referred to a health educator for one-to-one motivational counselling sessions to facilitate behaviour change. Behaviour change is facilitated through lifestyle medicine, which is ‘evidence-based practice of assisting individuals and families to adopt and sustain behaviours that can improve health and quality of life (QoL). Healthy behaviours could greatly influence future health and well-being, especially among patients with NCDs’.16 In the long run, improving the health of populations means that individuals, communities and organisations need to change their behaviour to become healthier.17 The principal modifiable risk factors for CVDs and other NCDs include: tobacco use, an unhealthy diet and physical inactivity (which together result in obesity), hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes.18 Prevention, management or reversal of the modifiable risk factors can be achieved through leading a healthier lifestyle.19

When considering the reduction of CVDs, the most damaging risk factor in terms of attributable DALYs is hypertension.4 Hypertension is defined as blood pressure of above 140/90 mm Hg according to the European Society of Cardiology.20 The prevalence of hypertension is available in a few Kosovar studies, but no data on hypertension control is yet available. One cross-sectional study (n=423, mean age 51 years) of two rural predominantly ethnic-Serb communities in Kosovo found a hypertension prevalence of 42%.21 Another cross-sectional study of PHC users (n=1793, mean age 51 years) in the capital city of Pristina found a prevalence of hypertension at 33.6% (39% in men and 29% in women).22 A third cross-sectional study in 20 villages with a mixture of ethnic-Serbs and ethnic-Albanians found a hypertension prevalence of 30.6% (mean age men=62 years, women=49 years).23

The state of other risk factors for CVDs in Kosovo is even less well known. Although one study showed that 18% of older adults self-reported a diagnosis of DM,3 it is suspected that DM is highly underdiagnosed in Kosovo, indicating a large diagnostic gap. For example, another population study (n=423) conducted in 2006 assessing the prevalence of kidney disease (a positive family history for Balkan Endemic Nephropathy, mild proteinuria, alpha 1-microglobulinuria, eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, anaemia, low specific gravity of urine and reduced kidney length) in adults aged 18 years and older living in 2 Serbian settlements in the municipality of Rahovec found that 13% of participants had a previous diagnosis of diabetes but 21% (n=89) still had a pathological glycaemia finding (fasting blood glucose >6.1 mmol/L).24 Although all residents aged 18 years and above in the two settlements were eligible to participate in the study, the methodology in recruitment was not specified. Some studies on physical activity are available on Kosovar adolescents,25 but no evidence is available for adults. Similarly, evidence on tobacco use in Kosovo has been focused on school children and adolescents. However, a recent publication on the WHO Stepwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) survey of persons aged 15–64 years conducted in 2010 (n=6400) showed that 37% of men and 20% of women in Kosovo smoke.26 The prevalence increased with age until it dropped at age 45. The results from the same STEPS survey on physical activity, diet and cholesterol have not yet been published. The AQH project conducted a population-based study in 12 municipalities, with the aim to collect primary data on project indicators for a baseline against which the impact of the project activities will be measured. The study found that 20.6% of respondents smoked, 15% had ever consumed alcohol and 46% did not meet WHO recommendations on physical activity.27

In summary, more information is needed about NCD risk factors in the context of Kosovo and the impact of current interventions aimed at their reduction for a better understanding of where to target PHC services.

Mental disorders and their relationship with hypertension

CVDs and mental disorders are among the most burdensome NCDs to global health. It is furthermore disconcerting that there is a well-established bidirectional relationship between CVDs such as coronary artery disease and mental disorders like depression.28 In PHC, the prevention of CVDs is a high priority. Thus, the relationship between depression and risk factors of CVDs such as hypertension is of great relevance for the public health sector. According to a meta-analysis of 41 cross-sectional studies,29 the prevalence of depression in patients with hypertension was much higher than in the general population (26.8% compared with 4.4%), suggesting that the two are strongly connected.

Potential mechanisms linking depression and hypertension

Some mechanisms have been proposed to explain how depression is linked to hypertension. First, people living with depression tend to have unhealthy lifestyles which include habits such as smoking, alcohol abuse and physical inactivity,30 all of which are risk factors for hypertension and CVDs. Second, depression can cause autonomic nervous system dysfunctions which activates sympathetic activities31 thereby elevating blood pressure. Insomnia and short sleep duration, which are typical symptoms of some forms of depression, have been found to significantly increase the risk of hypertension incidence.32 33 Little sleep can activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which raises blood pressure in the short term, and can lead to long-term structural adaptation that gradually reset the cardiovascular system to operate at an elevated pressure equilibrium. Finally, beyond its role in the aetiology of hypertension and CVDs, the presence of depression may also affect the treatment of hypertension. It was found that physicians were more cautious with augmenting antihypertensive treatment in people with depression34 because some antihypertensive medications have been found to cause or worsen depression.35 This means that depressed persons may be less likely to receive adequate treatment from their physician for their blood pressure. In another sense, depression is a risk factor for poor adherence to antihypertensive medication.36

The literature thus far explores the association of depression with three main facets of hypertension: the incidence of hypertension among those with previous normal blood pressure, the control of blood pressure among those with a previous diagnosis of hypertension and the course of blood pressure on a continuous scale.

Evidence on depression and hypertension incidence

The goal of primary prevention in PHC in terms of blood pressure is to prevent people from developing hypertension. According to a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, depression significantly increased the risk of incident hypertension (RR 1.42; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.86).37 However, authors cautioned that the limited number of longitudinal studies available may have impacted conclusions. It should also be noted that definitions of hypertension differed among studies, which included either high blood pressure measurement (with differing cut-offs such as ≥140/90 mm Hg or ≥165/95 mm Hg), prescribed antihypertensive medication, physician diagnosis, self-reported hypertension or a combination of these. The inverse relationship (hypertension as a risk factor for incident depression) was assessed in another meta-analysis, which did not find a significant association.38 One possible explanation is that hypertension is often asymptomatic, having less impact on QoL and thus depression when compared with more advance stages of CVDs.

Evidence on depression and hypertension control

The goal of hypertension control in secondary prevention is for people with hypertension to reduce and maintain their blood pressure at a normal level through lifestyle changes and/or adhering to prescribed medication. Uncontrolled hypertension is the persistence of high blood pressure after a diagnosis of hypertension, which is a risk factor for developing CVDs. Despite being of great relevance for secondary and tertiary prevention in the public health sector, few studies have assessed the effect of depression on the control of hypertension among patients with hypertension. Depression was found to be positively associated with uncontrolled hypertension in a small cross-sectional study (RR 15.5; 95% CI, not reported; n=40),39 and a case-control study’s adjusted model (RR 1.94; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.85; n=590).40 In a large retrospective cohort study (n=210 482), the authors found a significant association between depression and uncontrolled hypertension in their secondary analysis (OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.26).41

Evidence on depression and the course of blood pressure

Looking at blood pressure on a continuous scale is also of interest to better understand the magnitude depression can impact blood pressure. One cross-sectional study (n=2981) found that depressed subjects had lower mean systolic blood pressure than controls, and tricyclic antidepressant users had higher mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure.42 A recent longitudinal study in Germany (n=1887) also found that after 12 years of follow-up, a history of moderate major depressive disorder was associated with a decrease in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.43 Since depressive symptoms vary over time, this study was limited by its definition of depression (a lifetime history of depression) because conclusions about the relative effect of short-term and long-term depressive symptoms could not be made. The importance of evaluating depressive symptoms in parallel to blood pressure over time was noted in another longitudinal study in Norway,44 which also found that baseline depression predicted lower blood pressure at year 22, but further found that a high symptom level of depression and anxiety at baseline and year 11 was more strongly associated with a decrease in blood pressure at year 22, and associated with an even stronger decrease in blood pressure if there were high levels of symptoms at all three examinations.

Other emotional states such as anxiety and stress have overlapping symptomology with depression but are distinct negative emotional states. The independent associations between anxiety and stress with hypertension have been studied.

Evidence on anxiety and hypertension

According to the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), which differentiates the three emotional states, symptoms of anxiety include autonomic arousal (heart rate increase, mouth dryness, etc), skeletal muscle effects (trembling), feelings of panic, faintness or being terrified for no good reason.45 A meta-analysis which pooled 13 cross-sectional studies with 151 389 subjects found a significant positive association between anxiety and hypertension (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.62).46 Although significant publication bias was detected, the OR remained significant after trim and fill analysis (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.37). In the same meta-analysis, eight prospective studies on baseline anxiety and incident hypertension were pooled (n=80 146) and presented a HR by random effect model of 1.55 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.94) with strong heterogeneity (p<0.001, I2=84.6%) but no publication bias was detected (p=0.663). Although there are clear relationships, the mechanisms for them are not yet well understood.

Evidence on stress and hypertension

Symptoms of stress included in the DASS are difficulty relaxing, nervous arousal, getting easily upset or agitated, irritable/over-reactive and impatience.45 In a recent meta-analysis (n=5696) of 11 studies, domains of mental stress were defined as psychological stress, anxiety/depression or work stress.47 Two studies (n=622) looked at the association of mental stress on the risk of hypertension (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.49, I2=0%, p=0.33) and the other nine studies looked at the association of hypertension on the risk of mental stress (OR=2.69, 95% CI 2.32 to 3.11). The limitation of studies on stress and hypertension, as seen in the meta-analysis, are that they are few in numbers and have varying definitions of stress, which in some cases include depression and anxiety. Therefore, more studies are needed on the relationship between stress and hypertension, with a clear definition of stress as a distinct emotional state.

Mental healthcare in Kosovo

Supporting persons with mental illness in Kosovo is a challenge. This is because mental health services are only available on referral to a specialist, which may deter persons with mental illness from seeking care as it remains highly stigmatised in the country. Seeking professional support to address mental health problems is associated with ‘tremendous shame’ in the country; thus, support is rarely requested or is kept within the family circle.48 Indeed, only 15% of people who stated they needed help actually sought the help from a psychologist or psychiatrist due to fear of being stigmatised.11 If help for mental illness is sought outside the home, families often consult with traditional healers or local religious persons instead of mental health professionals.48

In summary, further research is needed to make sense of the inconsistencies in the literature between depression and the different facets of hypertension. Understanding potential mutual influences between depression and hypertension in Kosovo is highly relevant, as it could indicate the need for integrated mental health services in PHC, especially given that both depression and hypertension are common and standalone mental health services are stigmatised. Integrated mental health services have been found to be effective in another setting49 for more effective control of both depression and hypertension.

Objectives of the KOSCO study

The overarching goal of the 5-year KOSCO study is to contribute epidemiological evidence to the prevention and control of NCDs in Kosovo as the basis for policy and decision-making, which is currently lacking in the country. Specific objectives include:

To assess the prevalence and temporal change of NCDs such as hypertension, depression, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as well as the prevalence and temporal change of aetiological risk factors, disease control and underdiagnosis of these NCDs among PHC users.

To evaluate the longitudinal relationship of PHC non-experimental interventions such as motivational counselling sessions with adherence to healthy lifestyles (physical activity, nutrition, smoking, alcohol consumption), clinical measurements (blood pressure, BMI and HbA1c) and the stage of health behaviour change.

To assess the predictive association between depression and the course of blood pressure in adult PHC users living in Kosovo, as well as the mediators of the association.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This prospective 5-year longitudinal study of PHC users in Kosovo conducted follow-ups annually in two phases, spaced by approximately 6 months. Part 1 included an in-person interview and health examination, while part 2 included a telephone interview. Part 1 of baseline data collection began in March 2019 and part 2 began in October 2019. The second follow-up started in March 2020. Annual follow-ups during a 5-year cohort allows for potential mediation analysis.

Setting

The study was conducted in Kosovo, which is located in the centre of the Balkans and the newest independent state in Europe, although not accepted as such by all countries. It has a population of 1.8 million and is divided into 38 municipalities over a surface area of nearly 11 000 km2. The country has mainly rural settlements (62%), ethnic-Albanians with minorities of Serbian, Roma, Ashkali, Egyptian (RAE), Bosnians and Turkish ethnicities and has a male-to-female ratio of 1.06.5 Study sites included the 12 MFMCs from the following municipalities in Kosovo: Fushë Kosovë, Drenas, Gračanica, Gjakovë, Junik, Lipjan, Malishevë, Mitrovicë, Obiliq, Rahovec, Skënderaj and Vushtrri. There exists only one MFMC per municipality.

The study was embedded within the AQH project and the selection of municipalities was based on the project’s established stakeholder collaboration. The AQH project engaged with these municipalities based on nine indicators: RAE population as percentage of total population, per capita public expenditure, per capita total PHC financing, social welfare beneficiaries per 100 inhabitants, female lone parent as percentage of female population, doctors per 1000 inhabitants, nurses per 1000 inhabitants, total PHC visits per capita, diarrhoea per 1000 inhabitants and applying a convenience sample to ensure geographical clustering and representation of ethnic-Serbs.

Participants

The study population included adults aged 40 years or older who consulted healthcare services at one of the 12 study sites on the day of recruitment. Persons were excluded from participating in the study if (1) they had a terminal illness, (2) were not able to understand or respond to prescreening questions, (3) did not live in 1 of the 12 study municipalities or (4) live abroad for more than 6 months of the year. Patients exiting the 12 participating MFMCs were approached consecutively and screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from participants in a quiet room of the MFMC. Research nurses alternated municipalities in their study clusters each week of recruitment (Cluster 1: Gračanica, Drenas, Skënderaj. Cluster 2: Malishevë, Rahovec, Gjakovë, Junik. Cluster 3: Fushë Kosovë, Vushtrri, Mitrovicë. Cluster 4: Lipjan, Obiliq). Clusters were developed based on the proximity of municipalities to each other and the number of participants to be recruited per municipality to balance the workload of each research nurse.

Incentive

As a participant of the cohort, one was entitled to the following incentives: waived copayments of one health consultation and associated blood tests once per year, and an HbA1c test was free of charge to the participant on the day of each in-person interview.

Study preparation

Four research nurses were hired to conduct the data collection. They participated in a 3-day training certified by the Kosovo Nursing Chamber which covered standard operating procedures (SOP) to perform interviews and health assessments. One week prior to recruitment, research nurses and the field research coordinator visited all sites to meet and inform relevant staff about the study and ensure necessary on-site equipment was ready for use. A plan of the recruitment schedule, which rotated between study sites, was provided to all directors.

Patient and public involvement

Public stakeholder involvement in study design

Directors of the MFMCs were invited for meetings to discuss the study in October 2018 and in February 2019 (5 months and again 3 weeks prior to the launch of the recruitment of participants, respectively). In these meetings, the purpose and methods of the study were presented. Stakeholder feedback on logistical issues and health priorities in the regions were adapted into the protocol. For example, directors of PHC facilities asked to include data collection on respiratory health since their clinical experience indicated that it was a public health concern with lacking epidemiological evidence in the area. Considering the decentralised system, a signed agreement with all 12 directors of the MFMCs was established for their voluntary participation in the cohort.

Patient involvement in piloting the interview guide

The interview guide was piloted on a convenience sample of nine PHC patients from the MFMC in Obiliq. The questions were adapted according to patient feedback (eg, some questions were repetitive or not culturally appropriate, therefore removed). The first follow-up questionnaire was piloted on 42 cohort participants and the questionnaire was again modified based on feedback.

Variables and data collection

Interviews

The interview guide of the cohort addressed many objectives and was therefore lengthy. To reduce the risk of participant fatigue, the interview guide was divided into two parts, spaced by an interval of approximately 6 months. Part 1 of the interview was conducted in-person at the MFMC by a trained research nurse (approximately 30 min duration) and part 2 of the interview was conducted by telephone (approximately 20 min duration). Refer to table 1 for an overview of variables measured in each of the two parts of baseline data collection which are grouped by theme, and table 2 for a description of validated instruments used.

Table 1.

Overview of variables measured in participant interviews and health examinations

| Theme | Variables | Part 1: in-person interview | Part 2: telephone interview |

| Sociodemographic factors | Age, gender, marital status, residence, ethnicity, education level, occupation, household composition, income level, pension, health insurance | x | |

| Social and environmental factors | Social support, proximity to health services | x | |

| Health factors, block I | Health literacy, current diagnoses, family history, comorbidities, symptoms, self-care/health related self-efficacy, disability, sleep, medications, complications of CVDs | x | Repeat only: comorbidities, symptoms, complications of CVDs |

| Health factors, block II | Somatic symptoms | x | |

| Health system factors | Provider adherence to treatment protocol, healthcare utilisation, patient satisfaction with services | x | Repeat only: provider adherence to protocol, healthcare utilisation |

| Lifestyle behaviour, block I | Smoking, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity | x | x |

| Lifestyle behaviours, block II | Health behaviours and stages of change, Health specific self-efficacy | x | |

| Psychological factors, block I | Depression, anxiety, stress, resilience, post-traumatic stress disorder, quality of life | x | Repeat only: depression, anxiety, stress, quality of life. Add: previous diagnosis of mental illness |

| Psychological factors, block II | General self-esteem | x | |

| Health examination | Blood pressure, height, weight, waist/hip/neck circumferences, HbA1c, peak expiratory flow | x |

CVD, cardiovascular diseases.

Table 2.

Overview of validated instruments used in interviews

| Theme | Questionnaire | Description |

| Sociodemographic factors | None | |

| Social and environmental factors | Modified Medical Outcome Survey Social Support Scale (mMOS-SSS) | The mMOS-SSS is an 8-item measure of the availability of different kinds of social support scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from: 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The higher the total score, the more perceived support.55 |

| Health factors, part I | Self-report generated Charlson Comorbidity Index (SRG-CCI) | The SRG-CCI is an index consisting of 10 comorbidity categories and have associated weights ranging from 1 to 6 based on risk of mortality or resource use.56 The sum of all the weights results in a single comorbidity score for a patient. The higher the score, the more likely the predicted outcome will result in mortality or higher resource use. |

| Rose Angina Questionnaire (RAQ) | RAQ was developed to detect ischaemic heart pain (angina pectoris and myocardial infarction) for epidemiological field surveys.57 Angina pectoris is indicated by responses to seven questions and possible myocardial infarction is indicated by response to a single question. Five items have binary response options and three items are categorical. | |

| European Community Respiratory Health Survey II (ECRHS II) Main Questionnaire | A selection of 14 items from the ECRHS II Main questionnaire was included to assess respiratory symptoms. Items assess the presence of wheezing, tightness in chest, shortness of breath, cough and phlegm with binary responses.58 | |

| Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale | The MRC Dyspnea Scale was developed to categorise the level of disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.59 The scale has one item with five levels which range from ‘not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise’ to ‘too breathless to leave the house, or breathless when dressing/undressing’. | |

| Health factors, part II | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ15) | PHQ15 is a 15-item somatic symptom scale which measures the severity of somatisation in patients60. Items relate to 15 physical symptoms experienced in the past 4 weeks, with responses rated on a 3-point Likert scale 0 (‘not bothered at all’) to 2 (‘bothered a lot’). The summary score ranges 0–30 and classified as minimal (0–4); mild (5–9); moderate (10–14) and high (15–30) severity of somatic symptoms. |

| Health system factors | European Task Force on Patient Evaluations of General Practice Care (EUROPEP) | Europep is a 23-item questionnaire which measures patient satisfaction with primary healthcare services such as doctor–patient relationship; medical care; information and support; continuity and cooperation, and accessibility61. All items are aggregated into two dimensions: clinical behaviour (items 1–16) and organisation of care (items 17–23). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). |

| Lifestyle behaviour, part I | None | |

| Lifestyle behaviours, part II | Stages of Change Survey | The Stages of Change Survey assesses the stage of lifestyle change based on the stages of change model and has one item with five statements for each type of lifestyle behaviour (smoking, alcohol consumption, nutritional consultation, physical activity) which represent different stages of change. Participants must choose from the list of statements which most closely matches what they currently do.62 |

| Smoking Abstinence Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SASEQ) | SASEQ has six items with statements of various situations where one might be tempted to smoke and asks for the participant’s confidence level that they will not smoke.63 Response options are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from certainly (4) to certainly not (0). | |

| Health-Specific Self-Efficacy Scales (HSSES) | The HSSES assesses a person’s optimistic self-belief about being capable to resist temptations and to adopt a healthy lifestyle64. The question ‘How certain are you that you could overcome the following barriers?’ is followed by a list of barriers for each of the following lifestyle behaviours: nutrition (five items), physical exercise (five items) and alcohol consumption (three items). Response options range on a 4-point Likert scale from (1) very uncertain to (4) very certain. | |

| RAND-12 Health Status Inventory (RAND-12 HSI) | The RAND-12 HSI is a 12-item version of the RAND-36 HSI, which measures health-related quality of life.65 The RAND-12 HSI provides estimated scores on Physical Health, Mental Health and Global Health composites of the 36-item instrument. The RAND-12 HSI uses the item response theory (IRT) and oblique (correlated) factor rotations to generate the physical and mental health summaries.65 The composite scores range from 0 to 100, where a 0 score indicates the lowest level of health and 100 indicates the highest level of health. | |

| Psychological factors, part I | Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS-21) | Depression, anxiety and stress were measured using the DASS-21,45 66 a 21-item questionnaire consisting of three subscales, each containing seven items scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much), and multiplied by 2. The scores are classified as depression 0–9 (normal), 10–13 (mild), 14–20 (moderate), 21–27 (severe), ≥28 (very severe); anxiety 0–7 (normal), 8–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), 15–19 (severe) ≥20 (very severe); stress 0–14 (normal); 15–18 (mild), 19–25 (moderate), 26–33 (severe), ≥34 (very severe). |

| Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5) | PC-PTSD-5 is a 5-item screen designed for primary care settings. The first item assesses whether the respondent has had any exposure to traumatic events. If a respondent denies exposure, the PC-PTSD-5 is complete with a score of 0. However, if a respondent indicates that they have experienced a traumatic event over the course of their life, five additional items are asked regarding how that trauma exposure has affected them over the past month. Each item receives a binary score: 0 (no) or 1 (yes). The scores are classified as: ≤2 (improbable PTSD) and ≥3 (probably PTSD).67 | |

| Resilience Scale (RS-14) | RS-14 is a 14-item questionnaire that assesses individual resilience in a general population.68 Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores are categorised into very low (14–56), low (57–64), on the low end (65–73), moderate (74–81), moderately high (82–90) and high (91–98). | |

| Psychological factors, part II | Self-esteem (SE) | SE is a 1-item scale developed as an alternative to the Rosenberg self-esteem scale69. It is measured on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not true of me) to 7 (very true of me). |

| Health examination | Not applicable |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Data collection was divided into two parts: in-person interviews with health examination (part 1) and telephone interviews (part 2). Variables assessed are grouped by theme, and inclusion in part 1 and/or 2 is indicated with an ‘x’ or with comments.

Validated instruments used in each of the interview themes are described in the table. Questions developed by the study team and questions from non-validated questionnaires are not included in the table.

Physical examination

Immediately following the in-person interview, the research nurse performed a brief health examination of about 10 min.

Height (cm) and weight (kg) were measured using stadiometers and scales which were available at the MFMCs (various brands). The precision of scales was assessed regularly with a weight of 10 kg. Circumferences of the waist, hip and neck were measured using the SECA 201 measuring tape (Seca GmbH & Co. KG., Switzerland).

Peak expiratory flow (PEF) (L/min) was measured 3 times with 30 s pause between attempts, using the OMRON Peak Flow Meter PFM20 (Omron Healthcare, Switzerland). PEF predicted (%) was calculated as follows: estimated (measured) PEF/expected PEF. The expected PEF values were derived based on age, gender and height using the regression equation developed by Hankinson et al.50

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (in mm Hg) were measured three times, at least 3 min apart, after sitting quietly for about 10 min, using an M3 model Omron blood pressure monitor (Omron Healthcare, Switzerland). The research nurses placed the blood pressure cuff 2 cm above the elbow on the bare left upper arm (in the case of arteriovenous fistula, radiotherapy or removal of lymph nodes in the armpit of the left arm, the right arm was used) of the seated participant and elevated the arm on the table to the level of the fourth intercostal space.

Towards the end of the battery of tests, the research nurse accompanied participants to the laboratory of the MFMC for a finger-prick (non-invasive) glycated haemoglobin test (HbA1c, %). The HbA1c test was performed by an MFMC staffed laboratory technician who received training by the supplier on how to use the SUPER ID clinchem device (Dr. Müller Gerätebau GmbH, Germany).

Participants were given a ‘self-care passport’ at baseline, which was developed by local experts in collaboration with the AQH project. The research nurses transcribed the participants’ health examination results in the passport which also had additional space for participants to write blood pressure or blood glucose measurements taken at home. Participants were instructed that they will be recontacted in 6 months for a telephone interview.

Definitions of main variables by objective

Objective 1

Depression was defined as self-reported depression diagnosis by a healthcare professional and/or prescribed antidepressant medications and/or a DASS depression score of >13 (moderate to very severe depressive symptoms). Uncontrolled depression was defined as being diagnosed with depression and/or taking antidepressant medication yet having a DASS depression score of >13. Undiagnosed depression was defined as not being diagnosed with depression nor taking antidepressant medication yet having a DASS depression score of >13

Hypertension was defined as a self-reported hypertension diagnosis by a healthcare professional and/or prescribed antihypertensive medications and/or a blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mm Hg. Uncontrolled hypertension was defined as being diagnosed with hypertension and/or taking antihypertensive medication yet having a blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mm Hg. Undiagnosed hypertension was defined as not being diagnosed with hypertension nor taking antihypertensive medication yet having a blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mm Hg.

Diabetes was defined as a self-reported diabetes diagnosis by a healthcare professional and/or prescribed antidiabetic medications and/or an HbA1c measurement ≥6.5%. Uncontrolled diabetes was defined as being diagnosed with diabetes and/or taking antidiabetic medication yet having an HbA1c measurement ≥6.5%. Undiagnosed diabetes was defined as not being diagnosed with diabetes nor taking antidiabetic medication yet having an HbA1c measurement ≥6.5%.

COPD was defined as a self-reported COPD diagnosis by a healthcare professional and/or a PEF <80% predicted with breathlessness and/or cough symptoms for greater than 6 months. Uncontrolled COPD was defined as being diagnosed with COPD yet having a PEF <80% predicted. Undiagnosed COPD was defined as not being diagnosed with COPD yet having a PEF <80% predicted with breathlessness and/or cough symptoms for greater than 6 months. A PEF <80% predicted with respiratory symptoms (breathlessness or cough for greater than 6 months) was found to be an appropriate cut-off to detect COPD in the absence of spirometry.51

Lifestyle factors included: smoking (current smoker, ex-smoker, never smoker), meeting WHO recommendations for physical activity (at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or at least 75 min of vigorous-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or an equivalent combination of moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activity52), meeting WHO recommendations for fruit and vegetable intake (at least five portions (400 g) of fruits and vegetables per day53), binge drinking (consumption of ≥60 g of pure alcohol (six or more standard drinks) on at least one single occasion at least once in a month54), and BMI: weight (kg)/height (m2).

Objective 2

Motivational counselling sessions: are a non-experimental community intervention, where all patients being treated at a MFMC, FMC or FMA aged 40 or older with diabetes, hypertension or at risk for developing diabetes and/or hypertension are eligible to be referred by a doctor or nurse to the nearest health resource centre. There, the nurse provides one-on-one motivational counselling sessions on lifestyle changes based on the patient’s needs. Prior to rolling out this intervention, several preparatory steps were undertaken by the AQH project. First, health resource centres were established within MFMCs as a new location for nurses to provide motivational counselling sessions and other preventive services for management of NCDs. Furthermore, nurses from MFMCs completed several training sessions on motivational counselling. At the time of baseline, motivational counselling was offered in 5 of the 12 study sites (Fushë Kosovë, Gjakovë, Malishevë, Mitrovicë and Vushtrri), and a staggered introduction of the intervention to other study sites is anticipated. Attending a motivational counselling session was the main exposure, a dichotomous variable where participants answered yes or no to the question: ‘Have you ever participated in a motivational counselling session/health education session with a nurse in a health resource centre?’

Lifestyle factors were among the main outcomes, described under ‘objective 1’.

Clinical measurements were among the main outcomes, which were continuous variables that included blood pressure, BMI and HbA1c described under ‘physical examination’.

Stage of behavioural change was one of the main outcomes, an ordinal variable assessed using the Stages of Change Survey. For each lifestyle (smoking, nutrition, physical activity and alcohol consumption), participants were categorised into one of the following stages of change based on their responses: maintenance, action, preparation, contemplation and precontemplation.

Patient satisfaction and quality of care were predictors included in the secondary analysis. Patient satisfaction was a binary variable defined as an average EUROPEP score per item of ≥4. Quality of care was a continuous variable defined as the number of patient-reported healthcare provider actions completed from the list of recommendations in the PEN protocol during the participant’s last visit in a PHC centre.

Objective 3

Depression was the main exposure, a dichotomous variable defined under ‘objective 1’.

Change in blood pressure was the main outcome, which was the blood pressure (described under ‘physical examination’) from baseline subtracted from blood pressure at follow-up.

Hypertension incidence, uncontrolled hypertension and underdiagnosed hypertension are secondary binary outcomes described under ‘objective 1’.

Non-participants

Non-participants (patients approached who declined to participate or who did not meet inclusion criteria) were asked nine optional questions with the purpose to understand if participants differ from non-participants. The optional questions provided information on sex, age, education level, diagnosis of diabetes, lung disease, CVD, smoking status, weight, level of satisfaction with PHC services and reason for non-participation.

Data management

Data from in-person and telephone interviews were collected using Open Data Kit (ODK) software. Results from health examinations were also entered into ODK. Data quality was assured through (1) formulation of SOPs for all aspects of the study, (2) extensive and careful training of the study team according to the SOPs, (3) onsite supervision of field activities ensuring adherence to protocol and (4) regular monitoring and internal evaluation of data entry during the field visits. The ODK and STATA programmes kept track of all changes made to the data. All data were merged into a single database at the end of data entry using STATA V.15.1 (STATA Corporation).

Power calculation

Power calculation without local effects

The following is a power calculation for the longitudinal study of the association of change in blood pressure with depression in the case of a single homogenous population with the prevalence of depression d=40%. We denote the relative effect of the depression at baseline on the change of blood pressure at follow-up as tau. For a small effect tau=0.25, which under the normal distribution assumption corresponds to the shift from the median to the 60 percentile, and assuming a 20% loss to follow-up, we arrive at the minimal cohort size of 883 people for 90% power. The control for confounding variables will lead to a reduction of power, as will the discretisation of the blood pressure measurement to study hypertension as a binary outcome, and so we aim to recruit a total of 1000 patients into the cohort. The number of participants to be recruited by each MFMC was proportional to their mean number of medical visits in the months of June 2018 and October 2018.

Power in the presence of clustering

To take into account the potential local variation in the effect of depression on blood pressure, we performed explicit simulations to make sure that the study has sufficient power under a range of plausible scenarios. Specifically, we posited that the mean blood pressure can vary between the 12 municipalities (random effect with variance sigmaˆ2), and also that the effect of depression on blood pressure can be different in each municipality (random effect with variance rhoˆ2). The magnitudes sigma and rho of these local effects were tunable parameters of the simulation, as was the overall effect size tau. Preliminary analyses showed that the power of the study is driven by the relationship of tau and rho, and is not sensitive to sigma; this is because the municipality-level effect affects depressed and non-depressed people equally. Thus, we fixed sigma=tau in what follows.

For 18 combinations of plausible values of tau and rho, we simulated normal data on 800 participants (ie, the target cohort size minus 20% loss to follow-up) 10 000 times and computed the fraction of instances when the mixed regression model fitted on this synthetic data reported depression as a significant factor. This fraction can be interpreted as the statistical power of the study for the given tau and rho. The results of the simulations are reported in table 3 (rounded down to the nearest percent). We found that the study retains sufficient power for as long as the overall effect of depression dominates the local variation in that effect (that is tau is much greater than rho), which is likely. This requirement is progressively relaxed as the overall effect size grows.

Table 3.

Simulation of statistical power

| Tau=0.25 | Tau=0.30 | Tau=0.35 | Tau=0.4 | Tau=0.45 | Tau=0.5 | |

| Rho=0.1 | 80% | 91% | 97% | 99% | 99% | 99% |

| Rho=0.2 | 66% | 80% | 91% | 96% | 98% | 99% |

| Rho=0.3 | 49% | 65% | 77% | 87% | 93% | 97% |

The simulations did not take into account the loss of power due to adjustment for confounders.

Statistical analysis plan

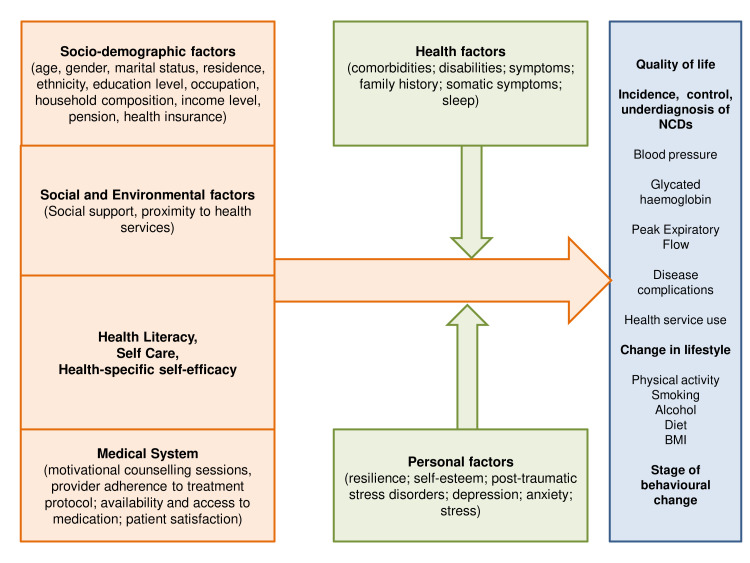

Figure 1 provides an overview of associations of interest for the cohort. Statistical methods are presented by objective.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised associations between variables under study. The hypothesised associations between outcome variables on the right, predictor variables on the left and mediating variables in the middle are represented in the figure. Sociodemographic factors, social and environmental factors, health literacy and self-care, as well as health system factors are thought to impact the outcome of quality of life, the incidence and control of chronic diseases and lifestyle change, and mediated by personal and health factors. BMI, body mass index; NCD, non-communicable disease.

Objective 1

The descriptive statistics of depression, hypertension, diabetes, COPD as well as the control and underdiagnoses of these diseases will be presented as follows: categorical variables will be presented as numbers and percentages. Normally distributed quantitative variables will be presented as mean and SD. Other quantitative variables will be presented as medians and IQRs. χ2 tests, t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests will be used for bivariate analysis where appropriate, such as to assess differences by age, gender or socioeconomic status (SES).

Objective 2

The main exposure of interest was attendance in motivational counselling sessions (non-experimental PHC intervention). In light of the absence of pure controls for this non-experimental intervention, comparisons will be made between those who chose to participate in the invention and those who did not within the same centre. The first outcome variable was stage of behaviour change, which was ordinal (maintenance, action, preparation, contemplation and precontemplation). Two approaches will be used: initially, the analysis will be done using ordinal regression, then the outcome variable will be split into two categories: (1) high motivation (maintenance, action, preparation) and (b) low motivation (contemplation and precontemplation) and logistic regression will be applied. The second outcome was adherence to the following aspects of healthy lifestyles: nutrition, physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking. Logistic regression analysis will be conducted for each lifestyle. For the third outcome (clinical measurements), a mixed linear regression model will be constructed for each outcome of interest: blood pressure, BMI and HbA1c. Comorbidities, physical ability, SES, living status and employment status are potential confounders and will be controlled for during data analysis. The intrinsic municipality and participant effects will be modelled with random effects. Potential effect modifiers include sex, age and social support. Self-efficacy will be considered as a potential mediator. Secondary analyses with predictors of patient satisfaction and quality of care will be conducted with logistic regression models.

Objective 3

The main outcome for this objective was change in blood pressure. Secondary outcomes included hypertension incidence, control and underdiagnosis. We will use an explanatory model with a focus on depression among predictor variables. Covariates systematically considered as confounders as well as effect modifiers in all models will be sex, age, urban/rural, ethnicity, education level and employment status. Additional covariates considered in some models include: smoking, alcohol, physical activity, obesity, family history, anxiety, stress, PTSD, resilience, social support, self-esteem, health literacy, healthcare seeking, patient satisfaction, comorbidity, sleep quality and duration, and medication. Antidepressant use and lifestyle factors will be assessed as a potential mediators.

Two approaches will be explored to assess the longitudinal association between depression and change in blood pressure.

Predictive perspective: a regression model will be constructed with the outcome of change in blood pressure from baseline (continuous). Baseline blood pressure will be adjusted for by including it as a covariate in the model. This model will allow predicting the future course of blood pressure, based on a set of variables observed at baseline. This model is of value for a provider perspective: based on what the provider observes at a specific point in time, what is the predicted course of blood pressure?

Change perspective: the effect of change in depression (predictor) on change in blood pressure (outcome) will be assessed with a repeated measures model. This model will allow assessing the parallel change in depression and blood pressure and in that sense takes cross-sectional short-term associations at baseline and follow-up into consideration.

Analyses with secondary outcomes of hypertension incidence, control and underdiagnosis will be conducted with logistic regression models. The secondary outcomes are relevant for primary and secondary prevention in PHC. Anxiety and stress will also be included as focal predictor variables in secondary analyses.

Strengths and limitations

Given the limited evidence on NCDs in Kosovo, the cohort is of great benefit for healthcare decision-makers which rely on health data. Results from this cohort study will provide an overall insight into the relationship between NCDs and their determinants through study objective 1. Considering that this study is assessing the longitudinal association of PHC interventions (such as delivery of motivational counselling sessions for behaviour change) in study objective 2, the scientific findings of this study can be applied in designing targeted behaviour change interventions. Behaviours affect morbidity, and extremely unhealthy behaviours may lead to mortality, therefore understanding what causes patients to do certain behaviours and what motivates them to change, provides information which could be useful for populations with similar characteristics.14 Further, understanding potential mutual influences between depression and hypertension could indicate the need for integrated mental health services in PHC for more effective control of both conditions,46 and will be addressed through objective 3.

Having embedded this cohort in an existing local implementation project, namely AQH which builds on strong partnerships with local stakeholders, greatly increased the ease of implementation and acceptability of this study. For example, the study population lives in mostly rural areas, with high levels of poverty and low levels of education which meant that there was little awareness of research and their benefits. Being embedded within the AQH project, which had established trust with municipalities, helped in the recruitment process. Further, given that the healthcare system is decentralised, getting directors of MFMCs from multiple municipalities on board to participate in the cohort study would normally be a long and complicated process, but was simplified since the directors had a longstanding relationship with the AQH project.

A pilot of the questionnaire with 9 PHC users aged 40 years and above conducted in March 2019 and in the MFMC of Obiliq and again in October 2019 with 42 cohort participants from various municipalities served to identify the understanding and flow of questions. Some questions were identified as inappropriate or irrelevant in the cultural context and were omitted. For example, the original PC-PTSD-5 questionnaire listed sexual abuse as an example of a traumatic event and this was considered offensive by one person in the pilot survey. Thus, the example was removed. One question asked if the participant had ever been diagnosed with a mental disorder by a physician. Local research nurses unanimously stated that this question was not culturally acceptable since it was not perceived well by the participants; therefore, it was removed from part 1 of the baseline data collection (initial contact with participants) and moved to part 2 to allow participants time to grow trust with research nurses. The PHQ asks questions about menstruation pain during intercourse, which were also culturally unacceptable and considered unpleasant to ask in an interview and a disclaimer statement was added before the items to preface the question. A question in the EUROPEP which assesses satisfaction with ‘getting through to the practice on telephone’ was removed as it is not common practice in Kosovo. Given that the average level of education in Kosovo’s older population is of primary school or lower, some instruments’ questions were abstract and difficult to understand by participants. In particular, respondents of the pilot survey noted that multiple questions in the RS-14 were difficult to understand, such as ‘I am friends with myself’ which was considered a Western ideal and ‘I keep interested in things’ often yielded participant questions like ‘what things?’ A debriefing with research nurses ensured that these questions were clarified with participants in a uniform way. It was confirmed through the pilot that the questionnaire was too lengthy, demonstrated by participants asking to end the interview before the end. It was decided to separate questions into two parts, asked with an interval of 6 months.

During the preparation period which involved site visits before the launch of recruitment, the first author learnt that lab hours were shorter than anticipated, which limited the amount of hours of recruitment (from 7:00 to 13:00). This meant that the original estimated recruitment timeline was extended from 3 months to 8 months. Further, participation rates were low, which extended recruitment time.

Due to the recruitment scheme in PHC facilities, the study is not population based. Thus, the study is limited in its generalisability as well as it may overestimate the prevalence of health conditions. However, patients visit MFMCs for an array of conditions as well as for general check-ups; thus, healthy persons are also included in the study. Providing participants incentives with free health consultations may bias towards participation of persons with chronic conditions, and thus may also overestimate the prevalence of NCDs and their determinants. The relevance of the study, in the absence of being entirely representative for Kosovo as a whole, lies in the longitudinal design; furthermore, it evaluates care and its perception and utilisation in a large number of relevant health service infrastructures. The findings will therefore be relevant and guiding for other similar structures in the country.

The non-randomised nature of PHC interventions mentioned in this study is a limitation in the interpretation of results regarding the effectiveness of interventions. But randomisation of interventions was not possible: centres offering the interventions were selected based on feasibility and interest of the MFMC staff to increase success of the pilot health centres, and the intervention is offered to all patients; therefore, exposure is self-selected.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approvals for the study were obtained from Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (reference number 2018-00994) on 11 December 2018 and the Kosovo Doctors Chamber (reference number 11/2019) obtained on 30 January 2019 and expiring on 31 December 2023. Before any data were collected, participants were asked for their verbal and written consent. To obtain consent, participants were informed that (1) their participation was voluntary, (2) they could withdraw from participation at any time and (3) non-participation would not have any negative effects. The participants were asked for additional consent whether, in the case a previously unrecognised medical problem was detected, they approve that qualified staff or the research team would inform them of the results and provide advice on what the participant should do next. SOP developed by the study team and approved by MFMC directors (who are physicians), were provided to research nurses to guide them in referring participants to appropriate care. Severe findings (systolic blood pressure ≥180 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥110) were referred immediately to emergency services in the MFMC. Participants were informed how the data will be used and that confidentiality is ensured as their data are coded. Potential risks and benefits of participation were also discussed with participants, and ample time was given to ask questions. Once consent was obtained, the research nurse proceeded to data collection.

Data protection

Data entry was done using a tablet (Samsung Galaxy Tab A, Samsung Group, Switzerland), where data were sent to a server and erased from tablets daily. Only participant identifiers, but not names of the participants were included in electronic health databases. HbA1c results were recorded in laboratories as per facility protocol with participant name, but not participant ID. Consent forms were kept in a locked file cabinet in Pristina, with restricted access to project personnel. Each participant has a code which is linked to their personal identifying data (PID) and a code linked to the study data (DID). The participant identifying information with PID is kept in one document stored by the Deputy Team Leader of the AQH project in Pristina, Kosovo. The DID, study data and key which links PID and DID are kept in a password-protected document with the principal investigator (NPH) in Basel, Switzerland.

Collaboration

The overall coordination of the cohort activities is the joint responsibility of the Board of Collaboration, which consists of two representatives from the University of Prishtina, two representatives of Swiss TPH and two representatives from National Institute of Public Health. Focus, content and protocols for follow-up assessments of the KOSCO study are approved by the Board of Collaboration.

Research questions assessed using cohort data will be published in scientific journals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The implementation of the cohort study protocol and prioritisation of study objectives would not be possible without the support of the Project Implementation Unit of the AQH project. Staff from 12 participating Main Family Medicine Centers (MFMCs) supported the study along with MFMC directors: Osman Maxhera (Fushë Kosovë), Kujtim Zarari (Gjakovë), Ismet Bogiqi (Drenas), Mirjana Dimitrijević (Gračanica), Ali Kuqi (Junik), Agim Krasniqi (Lipjan), Nuhi Morina (Malishevë), Fevzi Sylejmani (Mitrovicë), Haki Jashari (Obiliq), Jusuf Korenica (Rahovec), Fazli Kadriu (Skenderaj), Luljeta Zahiti-Preteni (Vushtrri). The KOSCO research nurses were instrumental in the success of recruitment and data collection: Tevide Bllaca, Arizona Igrishta, Selvete Zyberaj, Shqipe Agushi and Alma Stojanović.

Footnotes

Contributors: KAO: codeveloped and implemented the study protocol, coordinated and supervised data collection, will analyse and interpret data. NJ contributed to study objectives related to non-communicable diseases in Kosovo. SS contributed to study objectives related to mental health in Kosovo. MK conducted statistical power calculations and will supervise data analysis. MZ, QR, AB-K and JG contributed to the study objectives related to the evaluation of health service provision and to the integration of the study protocol within the AQH framework. NP-H developed the KOSCO cohort concept, study objectives and protocol, directed the implementation, data analysis and result interpretation. All authors read and approved the final protocol.

Funding: This work was supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). The first year of salary for the doctoral studies of KAO and the implementation and running costs of the cohort were funded by SDC, which is an agency in the federal administration of Switzerland and part of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, whom are responsible for coordinating Swiss international development projects in Eastern Europe. They are the core funders of the AQH implementation project in which the cohort is embedded. Local SDC representatives were responsible for approving the cohort budget and the study proposal. SDC contributed to the direction of study objectives. The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH) has internally funded the salary of KAO in the second and third years of the doctoral studies. Coauthors associated with Swiss TPH include KAO, JG, ABK, MZ and NPH and contributed to the study in various capacities, specified in authors’ contributions declaration. The Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship for Foreign Scholars and Artists was awarded to ABK for the time period of 2019-2022 (Reference number 2019.0234), which will fund her doctoral studies salary.

Competing interests: KAO, ABK and QR report personal fees from Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) during the conduct of the study. ABK reports grants from the Swiss Confederation during the conduct of the study.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approvals for the study were obtained from Ethics Committee Northwest and Central Switzerland (reference number 2018-00994) on 11 December 2018 and the Kosovo Doctors Chamber (reference number 11/2019) obtained on 30 January 2019 and expiring on 31 December 2023.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Bank Life expectancy at birth, total (years), 2017. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=XK-RS-AL-MK-ME [Accessed 22 Sep 2019].

- 2.Ahmeti M, Gashi M, Sadiku L, et al. Efficiency and effectiveness in implemention of unified and integrated health information system 2017;50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerliu N, Toçi E, Burazeri G, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic correlates of chronic morbidity among elderly people in Kosovo: a population-based survey. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:22. 10.1186/1471-2318-13-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation GBD results tool, 2016. Available: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool [Accessed 25 Jul 2018].

- 5.Kosovo Agency of Statistics Population by gender, ethnicity at settlement level, 2013. Available: http://ask.rks-gov.net/media/1614/population-by-gender-ethnicity-at-settlement-level.pdf [Accessed 30 May 2018].

- 6.Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001547. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel T, Rushiti F, Aghani F, et al. Suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress and suicide statistics in Kosovo 2009;19:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eytan A, Gex-Fabry M. Use of healthcare services 8 years after the war in Kosovo: role of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:638–43. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashdan TB, Morina N, Priebe S. Post-Traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and depression in survivors of the Kosovo war: experiential avoidance as a contributor to distress and quality of life. J Anxiety Disord 2009;23:185–96. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama R, Koyanagi A, Stickley A, et al. Social networks and mental health in post-conflict Mitrovica, Kosova. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1169. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shkcmbi F, Melonashi E, Fanaj N. Personal and public attitudes regarding help-seeking for mental problems among Kosovo students. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015;205:151–6. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringdal GI, Ringdal K. War experiences and general health among people in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo. J Trauma Stress 2016;29:49–55. 10.1002/jts.22074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Conference on primary health care. Declaration of Alma-Ata, 1978. Available: http://link.springer.com [Accessed 24 Jul 2018].

- 14.Clark DW, MacMahon B. Preventive medicine. little, brown, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Package of essential noncommunicable (Pen) disease interventions for primary health care in low-resource settings, 2010. Available: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/essential_ncd_interventions_lr_settings.pdf

- 16.Lianov L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA 2010;304:202–3. 10.1001/jama.2010.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somerville M, Kumaran K, Anderson R. Public health and epidemiology at a glance. Second edition Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2012. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Public+Health+and+Epidemiology+at+a+Glance%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9781118999325 [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Prevention of cardiovascular disease: guidelines for assessment and management risk of cardiovascular risk. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arena R, Guazzi M, Lianov L, et al. Healthy lifestyle interventions to combat noncommunicable disease-a novel nonhierarchical connectivity model for key stakeholders: a policy statement from the American heart association, European Society of cardiology, European association for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation, and American College of preventive medicine. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2097–109. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of cardiology and the European Society of hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of cardiology and the European Society of hypertension. J Hypertens 2018;36:1953–2041. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gorgieva GS, Stasević Z, Vasić S, et al. Screening of chronic diseases and chronic disease risk factors in two rural communities in Kosovo. Cent Eur J Public Health 2010;18:81–6. 10.21101/cejph.a3582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashani V, Hyska J, Roshi E. Socioeconomic determinants of hypertension in the adult population of transitional Kosovo 2013;5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markoglou NC, Hatzitolios AI, Savopoulos CG, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of hypertension in the civilians of Kosovo after the war. Cent Eur J Public Health 2005;13:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stasević Z, Gorgieva GS, Vasić S, et al. High prevalence of kidney disease in two rural communities in Kosovo and Metohia. Ren Fail 2010;32:541–6. 10.3109/08860221003706974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tishukaj F, Shalaj I, Gjaka M, et al. Physical fitness and anthropometric characteristics among adolescents living in urban or rural areas of Kosovo. BMC Public Health 2017;17:711. 10.1186/s12889-017-4727-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gashi S, Berisha M, Ramadani N, et al. Smoking behaviors in Kosova: results of steps survey. Zdr Varst 2017;56:158–65. 10.1515/sjph-2017-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Accessile Quality Healthcare Project. Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, and Behaviour: Non-Communicable Diseases, Child Health and Citizens’ Right to Health in Kosovo, 2016. Available: http://www.aqhproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/KAPB-Report-2016_English.pdf [Accessed 9 Sep 2019].

- 28.De Hert M, Detraux J, Vancampfort D. The intriguing relationship between coronary heart disease and mental disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2018;20:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Z, Li Y, Chen L, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients with hypertension. Medicine 2015;94:e1317 10.1097/MD.0000000000001317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonnet F, Irving K, Terra J-L, et al. Anxiety and depression are associated with unhealthy lifestyle in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2005;178:339–44. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koschke M, Boettger MK, Schulz S, et al. Autonomy of autonomic dysfunction in major depression. Psychosom Med 2009;71:852–60. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b8bb7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez-Mendoza J, Vgontzas AN, Liao D, et al. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration and incident hypertension: the Penn state cohort. Hypertension 2012;60:929–35. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Posner K, et al. Insomnia and sleep duration as mediators of the relationship between depression and hypertension incidence. Am J Hypertens 2010;23:62–9. 10.1038/ajh.2009.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moise N, Davidson KW, Chaplin W, et al. Depression and clinical inertia in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:818–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celano CM, Freudenreich O, Fernandez-Robles C, et al. Depressogenic effects of medications: a review. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:109–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eze-Nliam CM, Thombs BD, Lima BB, et al. The association of depression with adherence to antihypertensive medications: a systematic review. J Hypertens 2010;28:1785–95. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833b4a6f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng L, Chen D, Yang Y, et al. Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens 2012;30:842–51. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835080b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long J, Duan G, Tian W, et al. Hypertension and risk of depression in the elderly: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hum Hypertens 2015;29:478–82. 10.1038/jhh.2014.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubio-Guerra AF, Rodriguez-Lopez L, Vargas-Ayala G, et al. Depression increases the risk for uncontrolled hypertension. Exp Clin Cardiol 2013;18:10–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almas A, Patel J, Ghori U, et al. Depression is linked to uncontrolled hypertension: a case-control study from Karachi, Pakistan. J Ment Health 2014;23:292–6. 10.3109/09638237.2014.924047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elperin DT, Pelter MA, Deamer RL, et al. A large cohort study evaluating risk factors associated with uncontrolled hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2014;16:149–54. 10.1111/jch.12259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Licht CMM, de Geus EJC, Seldenrijk A, et al. Depression is associated with decreased blood pressure, but antidepressant use increases the risk for hypertension. Hypertension 2009;53:631–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.126698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Speerforck S, Dodoo-Schittko F, Brandstetter S, et al. 12-Year changes in cardiovascular risk factors in people with major depressive or bipolar disorder: a prospective cohort analysis in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019;269:565–76. 10.1007/s00406-018-0923-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]