Abstract

There are many examples of bioactive, disulfide rich peptides and proteins whose biological activity relies heavily on proper disulfide connectivity. Regioselective disulfide bond formation is a strategy for the synthesis of these bioactive peptides, but many of these methods suffer from a lack of orthogonality between pairs of protected cysteine (Cys) residues, efficiency, and high yields. Here, we show the utilization of 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide (PySeSePy) as a chemical tool for the removal of Cys-protecting groups and regioselective formation of disulfide bonds in peptides. We found that peptides containing either Cys(Mob) or Cys(Acm) groups treated with PySeSePy in TFA (with or without triisopropylsilane (TIS)) were converted to Cys-S–Se-Py adducts at 37 °C and various incubation times. This novel Cys-S–Se-Py adduct is able to be chemoselectively reduced by five-fold excess ascorbate at pH 4.5, a condition which should spare already installed peptide disulfide bonds from reduction. This chemoselective reduction by ascorbate will undoubtedly find utility in numerous biotechnological applications. We applied our new chemistry to the iodine-free synthesis of the human intestinal hormone guanylin, which contains two disulfide bonds. While we originally envisioned using ascorbate to chemoselectively reduce one of the formed Cys-S–Se-Py adducts to catalyze disulfide bond formation, we found that when pairs of Cys(Acm) residues were treated with PySeSePy in TFA, the second disulfide bond formed spontaneously. Spontaneous formation of the second disulfide is most likely driven by the formation of the thermodynamically favored diselenide (PySeSePy) from the two Cys-S–Se-Py adducts. Thus, we have developed a one-pot method for concomitant deprotection and disulfide bond formation of Cys(Acm) pairs in the presence of an existing disulfide bond.

Graphical Abstract

2,2´-Dipyridyl diselenide can deprotect Cys(Acm) and Cys(Mob) residues, converting them to a Cys-S–SePy adduct, which can then be chemoselectively reduced by ascorbate without reducing an existing disulfide bond. The chemoselective reduction of the S–Se bond by ascorbate has many potential applications. We showed the use of this deprotection scheme to synthesize guanylin, a human hormone that contains two disulfide bonds.

INTRODUCTION

There are many examples of bioactive, disulfide rich peptides and proteins such as the insulin superfamily1, 2, conotoxins3, 4, guanylin5, 6, designed peptide therapeutics7, apamin and analogs8,9, sarafatoxin10, cyclotides11,12, defensins13, elafin14, and atracotoxins15, 16, whose biological activity relies heavily on proper disulfide connectivity. Synthesis of these bioactive peptides and therapeutics relies upon methods for oxidative refolding or regioselective disulfide bond formation.17,18 Though many methods have been developed for regioselective disulfide bond formation, many of these methods suffer from a lack of orthogonality between pairs of protected cysteine (Cys) residues, efficiency, and high yields.19, 20

As has been reviewed extensively by Moroder using the Fmoc/But strategy of solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), pairs of S-trityl (S-Trt), S-methoxytrityl (S-Mmt), S-tert-butylmercapto (S-SBut), or S-2,4,6-trimethoxyphenylthio (S-Tmp) must be used to install the first disulfide bond in regioselective strategies involving orthogonal pairs of Cys-protecting groups.20–22 In the case of Cys(Trt) or Cys(Mmt) pairs, both protecting groups can be removed by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) used in the cleavage step from the solid support.23–26 In the case of Cys(SBut) or Cys(Tmp) pairs, thiol or phosphine reducing agents can be used for deprotection.25,26 In both cases, air-oxidation can then be used to install the first disulfide bond.

Common reducing agents lack chemoselectivity and must be avoided after formation of the first disulfide bond. For example, if a Cys(SBut) pair is used to install the first disulfide bond, then a Cys(Tmp) pair cannot be used later because reducing agents are required to remove the Tmp protecting group and these reducing agents would also disrupt the pre-existing disulfide bond.

We realized that this limitation might be overcome using chemistry recently developed by our group. We previously showed that the 2-thio(5-nitropyridyl) (5-Npys) protecting group could be removed chemoselectively from selenocysteine (Sec), but not Cys using ascorbate (Asc) in aqueous buffer at pH 4.5 as shown in Figure 1.27 Thus, reduction of a mixed aryl-selenosulfide bond by Asc is very facile, while the same reduction of a mixed aryl-disulfide bond by Asc is slow.

Figure 1: Removal of the 5-Npys group from Cys or Sec by ascorbolysis.

We previously found that Asc can reduce the Se–S bond of Sec(5-Npys) very easily, while the same reduction of the S–S bond of Cys(5-Npys) is very slow.27

This finding gave rise to the idea of developing a new selenium-containing deprotection reagent. Since 2,2’-dithiobis(5-nitropyridine) (DTNP) was used by our group previously for simultaneous deprotection/disulfide bond formation with a wide variety of Cys-protecting groups28–30, we reasoned that we may be able to use 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide (PySeSePy) or a substituted derivative, as a deprotection reagent. Use of PySeSePy to remove Cys-protecting groups would result in a mixed aryl-selenosulfide bond that could subsequently be removed by Asc as shown in Figure 2. Asc is a chemoselective reductant because it has been reported that it does not reduce peptide/protein disulfide bonds, or does so very slowly at neutral pH (and more slowly at acidic pH).31,32 As such it has been widely used in the so-called “biotin switch assay” to detect S-nitrosothiols in proteins.33–35

Figure 2: Proposed reduction of the S–Se bond of Cys(PySe) by Asc.

We found that reduction of Sec-Se–SPy with Asc was fast.27 In order to gain the same chemoselective advantage with Cys residues, we “switched” the position of sulfur and selenium through the use of PySeSePy and derivatives so as to create a Cys-S–SePy adduct.

We are aware of only two other reports of chemoselective reduction of disulfides in the literature. Both reports involve borohydride derivatives that can chemoselectively reduce aromatic disulfides preferentially over alkyl disulfides and are only compatible with organic solvents.36,37 Asc is gentle, highly soluble in aqueous buffer, and can chemoselectively reduce mixed aryl-selenosulfide bonds over typical disulfide bonds as illustrated in Figure 3. This is especially true at acidic pH (pH 4 to 5) where Asc is very effective at only reducing the Cys(PySe) adduct and not peptide disulfide bonds. At acidic pH, the pyridyl ring is protonated, activating the selenosulfide for attack. In addition, when pH = pKa = 4.21, half of the ascorbic acid in solution is present as the active enolate.

Figure 3: Advantage of chemoselective reduction of Cys(PySe) adducts by Asc compared to conventional reducing agents.

A) Conventional reducing agents such as thiols will reduce each S–S or S–Se bond as shown. B) Asc chemoseletively reduces the S–Se bond of Cys(PySe) adducts. Note that R represents a covalent modification of Cys that can be removed by typical reducing agents.

Herein, we report the utilization of PySeSePy as a chemical tool for the deprotection of some common Cys protecting groups with concomitant disulfide bond formation. We found that when treated with PySeSePy in TFA, peptides with Cys(Mob) and Cys(Acm) groups are converted to Cys(PySe). We then went on to reduce this resulting selenosulfide bond with Asc in buffer. Additionally, we show that PySeSePy can be utilized for the regioselective formation of disulfide bonds through the iodine-free synthesis of the human intestinal hormone, guanylin. Our PySeSePy technology was employed to form a second disulfide bond without reducing a pre-existing disulfide bond. The ability of Cys(PySe) residues to be reduced chemoselectively by Asc will undoubtedly find other future biotechnological applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Solvents for peptide synthesis and tetrahydrofuran for PySeSePy synthesis were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Fmoc-Cys(Acm)-OH, 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin SS (100–200 mesh), and 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate (HATU) for solid-phase synthesis were purchased from Advanced ChemTech (Louisville, KY). Fmoc-Cys(Mob)-OH was purchased from NovaBiochem (Burlington, MA). All other Fmoc-amino acids were purchased from RSsynthesis (Louisville, KY). L-Ascorbic acid (sodium salt), Triisopropylsilane (98%) and thioanisole (99%) scavengers, as well as selenium powder (200 mesh), 2-bromopyridyine (99%), and sodium borohydride for the synthesis of PySeSePy, were purchased from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, PA). Guanylin was purchased from CPC Scientific (Sunnyvale, CA). All other chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The HPLC system is from Shimadzu with a Symmetry® C18 −5 mm column from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA) (4.6 × 150 mm). Mass spectral analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems QTrap 4000 hybrid triple-quadrupole/linear ion trap liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (SciEx, Framingham, MA).

Peptide Synthesis.

Either Fmoc-Cys(Acm)-OH or Fmoc-Cys(Mob)-OH were used to synthesize model test peptides of sequence H-Pro-Thr-Val-Thr-Gly-Gly-Cys-Gly-OH (H-PTVTGGCG-OH). All peptides were synthesized on a 0.1 mmol scale using a glass vessel that was shaken with a model 75 Burrell wrist action shaker. For each batch, 300 mg of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin SS (100–200 mesh, AdvancedChemtech), was swelled in dichloromethane (DCM) for 30 min. The first amino acid was directly coupled to the resin using 2% N-methylmorpholine (NMM) in DCM, shaking for 1 h. The resin was then capped using 8:1:1 DCM:methanol:NMM. Subsequent amino acids were coupled (without preactivation) using 0.2 mmol of Fmoc-protected amino acid, 0.2 mmol of HATU coupling agent, and 2% NMM in dimethylformamide (DMF), shaking for 1 h. Between amino acid couplings, the Fmoc protecting group was removed via two 10 min agitations with 20% piperdine in DMF. Success of Fmoc removal steps and amino acid couplings were monitored qualitatively using a ninhydrin test.38 Removal of the final Fmoc protecting group completed the peptide synthesis. Peptides were cleaved from the resin via a 1.5 h reaction with a cleavage cocktail consisting of 96:2:2 TFA:TIS:water. Following cleavage, the resin was washed with TFA and DCM and the volume of the cleavage solution was reduced by evaporation with nitrogen gas. The peptide solution was then transferred by pipette into cold, anhydrous diethyl ether, where the peptides were observed to precipitate. Centrifugation at 3000 rpm on a clinical centrifuge (International Equipment Co., Boston, MA) for 10 min pelleted the peptide. Peptides were dried, then dissolved in a minimal amount of water:acetonitrile (80:20), lyophilized, and used without further purification.

Synthesis of 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide.

PySeSePy was synthesized following previously reported methods.39 Water (20 mL), in a round bottom flask containing 0.596 g (15.75 mmol) of sodium borohydride, was cooled on ice to 0 °C. To this, 92 mg (7.5 mmol) of elemental selenium was added with vigorous stirring. The reaction was warmed to room temperature and stirred for ~10 min. Another 92 mg (7.5 mmol) of elemental selenium was then added, the reaction warmed to 40 °C, and stirred until all selenium had dissolved (~35 min). A brown/red solution of disodium diselenide resulted, which was sealed with a rubber septum and purged under nitrogen gas. To the aqueous solution of disodium diselenide, 1.43 mL (15 mmol) of 2-bromopyridine in 40 mL of anhydrous THF was added under a flow of nitrogen gas, and refluxed for ~36 h. After reflux, a clear, dark yellow/green solution resulted. This solution was diluted with ~400 mL brine, extracted 8X with ethyl acetate, dried with magnesium sulfate, then concentrated via rotary evaporation to a thick orange oil. The resulting oil was column purified using 35 g silica and 80:20 hexane:ethyl acetate as the solvent. Yellow product was collected, concentrated, then dried, resulting in 952 mg of an orange solid (~49% yield). The correct product was verified via 1H- and 77Se- NMR and mass spectrometry.

Deprotection of Cys(Acm) and Cys(Mob) by 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide.

Lyophilized test peptide H-PTVTGGCG-OH, with either S-Acm or S-Mob protection on the Cys residue, was dissolved in cleavage cocktail consisting of either neat TFA, or TFA with addition of 2% TIS and/or 2% water, and the solution was divided into two aliquots. To one aliquot, 5-fold excess PySeSePy was added. Both aliquots were incubated either at room temperature, or in a 37 °C water bath for either 4 or 12 h. For all reactions, the final reaction volume was 1.0 – 1.5 mL and contained 1.7 – 2.5 mM peptide. After incubation, peptides were precipitated with cold diethyl either, pelleted via centrifugation (as described above), and dried using nitrogen gas. For purification; dried pellets were re-dissolved in minimal amounts of neat TFA, precipitated with cold ether, pelleted via centrifugation, and dried using nitrogen gas. Dried peptide pellets were then dissolved in water:acetonitrile (80:20), lyophilized, and analyzed without further purification.

Reduction of Cys(PySe) by ascorbate.

Lyophilized H-PTVTGGC(PySe)G-OH peptide (3 mg, 0.0035 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer pH = 4.5, and divided into two aliquots. To one aliquot, 5-fold excess (0.0177 mmol) L–ascorbic acid sodium salt was added, while buffer missing ascorbate was added to the control aliquot. Both aliquots were covered in foil, incubated for 4 h at 22 °C, then flash frozen and lyophilized. For purification; dried pellets were re-dissolved in minimal amounts of neat TFA, precipitated with cold ether, pelleted via centrifugation, and dried (all as described previously). Dried peptide pellets were then dissolved in water:acetonitrile (80:20), lyophilized, and analyzed without further purification.

Synthesis of guanylin.

Guanylin peptide of sequence H-Pro-Gly-Thr-Cys(Trt)-Glu-Ile-Cys(Acm)-Ala-Tyr-Ala-Ala-Cys(Trt)-Thr-Gly-Cys(Acm)-OH was synthesized on a 0.1mmol scale using standard solid phase peptide synthesis, as described above. The peptide was cleaved from the resin via a 1.5 h reaction with a cleavage cocktail consisting of 96:2:2 TFA:TIS:water. Following cleavage, the resin was washed with TFA and DCM and the volume of the cleavage solution was reduced by evaporation with nitrogen gas. The peptide solution was then transferred by pipette into cold, anhydrous diethyl ether, where the peptides were observed to precipitate. Centrifugation at 3000 rpm on a clinical centrifuge for 10 min pelleted the peptide. Guanylin peptide was dried, then dissolved in a minimal amount of water:acetonitrile (80:20), lyophilized, and used without further purification. The first disulfide bond between Cys4 & Cys12 was formed by dissolving 24 mg (0.015 mmol) of lyophilized peptide in 50 mL of 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer pH = 8.2, and stirred vigorously in a large round bottom flask for 40 h. Complete formation of the first disulfide bond was monitored qualitatively using Ellman’s regent. The reaction was frozen and lyophilized to remove water. The second disulfide bond (between Cys7 & Cys15) was formed by dissolving 5.6 mg (0.0035 mmol) lyophilized peptide in neat TFA, then divided into two aliquots. To one aliquot, 2.75 mg (0.00873 mmol) of PySeSePy, 20 μL of TIS, and 20 μL of water was added, then the reaction was filled to 1 mL with TFA. The second aliquot (control) was filled to 1 mL with neat TFA, then both aliquots were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. After incubation, excess TFA was blown off using nitrogen gas, and peptides were precipitated with cold diethyl ether, pelleted via centrifugation, and dried (all as described previously). Dried peptide pellets were then dissolved in water:acetonitrile (80:20), lyophilized, and analyzed without further purification.

Testing ability of ascorbate to reduce peptide disulfide bonds.

Guanylin synthesized in this study (lyophilized powder, (1.6 μmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 4.5. The sample was split into two aliquots, and five-fold excess ascorbate was added to one of the samples. To the other (control), no ascorbate was added. In addition, the guanylin standard (0.5 μmol, from CPC scientific) was dissolved in 1 mL of 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, and five-fold excess ascorbate was added. All samples were incubated at room temperature for 4 h, then flash frozen and lyophilized.

High Pressure Liquid Chromatography.

HPLC analysis of all samples was completed using a Shimadzu with a Symmetry® C18 5 μm column from Waters (4.6 × 150 mm). Aqueous and organic phases were 0.1% TFA in distilled, deionized water (buffer A) and 0.1% TFA in HPLC‐grade acetonitrile (buffer B), respectively. Beginning with 100% buffer A, buffer B was increased by 1% up to 50% over 50 min with a 1.4 mL/min gradient elution. Buffer B was then increased by 10% up to 100% over 5 min. This method was used for analysis of each sample. Peptide elution was monitored via absorbance at both 214 and 254 nm.

Mass Spectrometry.

Peptides were using an Applied Biosystems QTrap 4000 hybrid triple-quadrupole/linear ion trap liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer operating in positive ESI mode. Aliquots of peptide were injected into the sample loop with a guard column at 10 μL/min into a 100 μL/min mobile phase flow consisting of 50/50 water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Mass spectra were collected in linear ion trap mode, scanning from m/z 200–2000.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rationale.

As outlined in the Introduction, we sought out to develop a method to deprotect Cys residues using PySeSePy, with concomitant conversion to the Cys(PySe) adduct. We reasoned that the resulting S–Se bond of the Cys(PySe) adduct should be easy to reduce using Asc (especially at low pH), giving a chemoselective advantage to regioselective disulfide bond forming strategies that would also be free of the use of iodine as discussed below.

Synthesis of 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide.

PySeSePy is not commercially available. Thus, we began with the synthesis of PySeSePy by first reducing elemental selenium with sodium borohydride, then introducing 2-bromopyridine for a nucleophilic displacement reaction, using reported methodologies.39 The synthesis was completed giving 49% yield. Mass spectral (MS) analysis, 77Se-NMR, and 1H-NMR spectrograms of PySeSePy are given in Figure S1 and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information.

Use of 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide and ascorbate as a cysteine deprotection strategy.

With PySeSePy in hand, we went on to test its effectiveness as a deprotection reagent to convert Cys(Mob) to Cys(PySe). While we tested a variety of deprotection conditions, we found that quantitative deprotection of Cys(Mob) occurs using 5-fold excess PySeSePy after 4 h at 37 °C in TFA/water (98:2) as judged by the HPLC and MS analyses shown in Figure 4. A deprotection cocktail of TFA/TIS/water (96:2:2) for 4 h at 37 °C gave very similar results (data not shown). We note that in order for full deprotection of the Cys(Mob) peptide to be achieved, a reaction temperature at 37 °C is required. If the reaction is done at room temperature, 30% of the peptide remained protected as Cys(Mob) (data not shown).

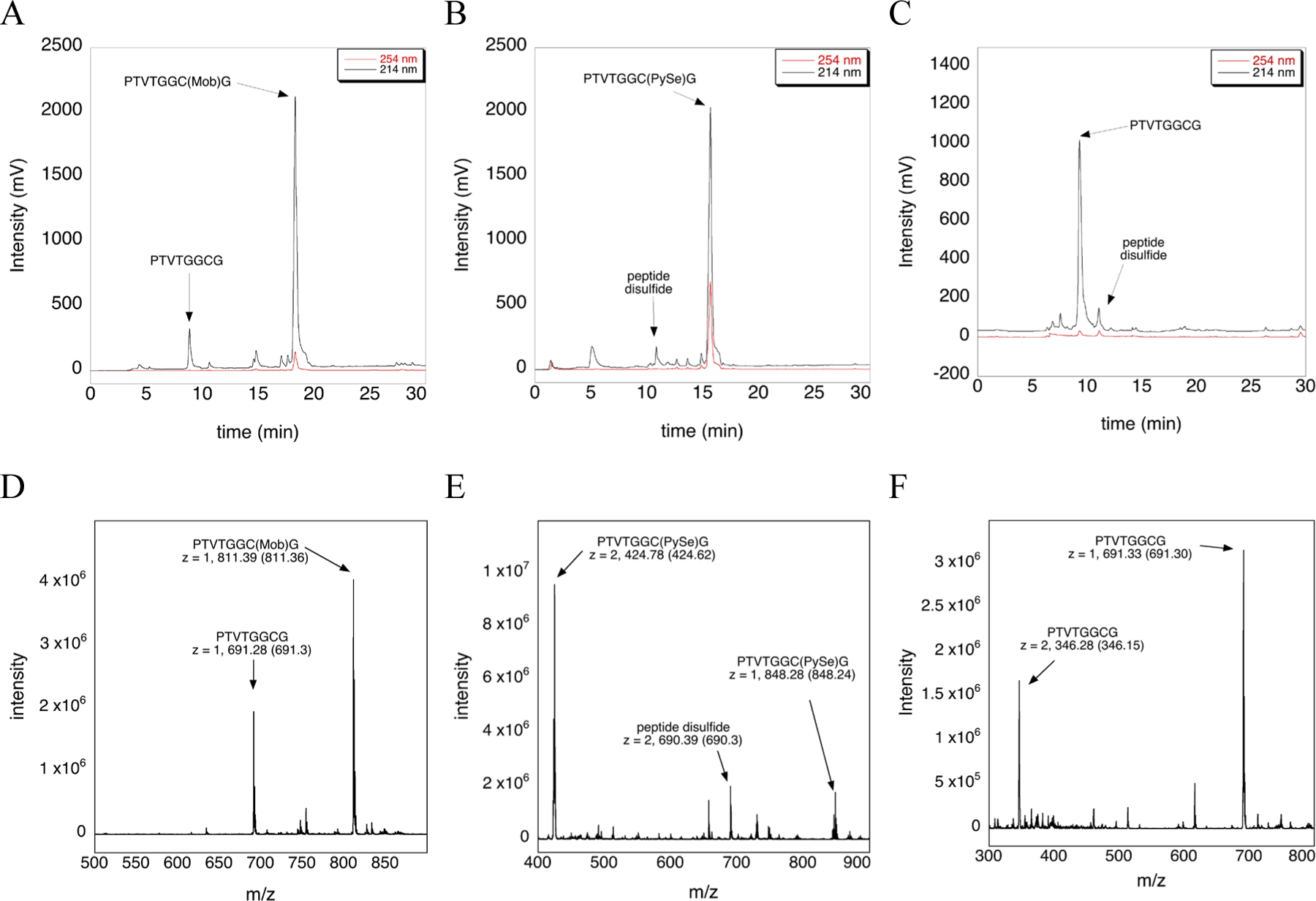

Figure 4: Deprotection of the Cys(Mob)-containing peptide using PySeSePy and Asc determined by HPLC and MS analyses.

A) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Mob)-containing peptide incubated in neat TFA for 4 h at 37 °C (control). B) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Mob)-containing peptide incubated in TFA/water (98:2) with 5-fold excess PySeSePy for 4 h at 37 °C. Quantitative conversion to the PySe-adduct is apparent. C) HPLC chromatogram of the peptide containing the Cys(PySe) adduct treated with 5-fold excess ascorbate in 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 4.5, for 4 h at room temperature. Panels D, E, and F are the mass spectra that correspond with panels A, B, and C, respectively. The arrow points to the observed m/z whereas the number inside the parentheses denotes the theoretical m/z value.

We then reduced the formed Cys(PySe) adduct with Asc. We found that the adduct could be reduced using 5-fold excess Asc in 100 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 4.5, after 4 h incubation at room temperature. The reduction of the Cys(PySe) adduct with Asc resulted in quantitative conversion to Cys-SH as shown in Figure 4C and 4F. Ascorbolysis of the S–Se bond may be achieved in a shorter time, but we did not test a shorter reaction condition.

We next turned our attention to the deprotection of Cys(Acm), which is significantly more difficult to deprotect than Cys(Mob). Deprotection of Cys(Acm) is commonly achieved by the use of iodine under acidic conditions with measures taken to suppress disulfide rearrangement.40–42 Our group showed that deprotection of Cys(Acm) could be achieved by using the gentle, electrophilic disulfide DTNP. However, the drawback to this method is that at least 20-fold excess DTNP and 2% thioanisole in TFA is required and deprotection was only achieved in 68% yield.29

We hypothesized that the deprotection of Cys(Acm) using PySeSePy could be achieved using similar conditions that were used above for the deprotection of Cys(Mob). We tested many conditions and found partial deprotection (~55%) using 5-fold excess PySeSePy in neat TFA at 37 °C for 12 h as judged by HPLC (Figure 5A). Interestingly we found that ~95% deprotection occurs under the same conditions, but with the addition of 2% TIS (Figure 5B). Our observation that TIS is required for deprotection agrees very well with our prior results in which we showed that addition of TIS to deprotection cocktails greatly enhances the removal of Mob and Acm groups from Cys.43,44 We found that TIS can directly reduce Cys(Acm) to Cys-SH in TFA at 37 °C for 12 h43, and this finding proved to be important in developing the deprotection of Cys(Acm) by PySeSePy.

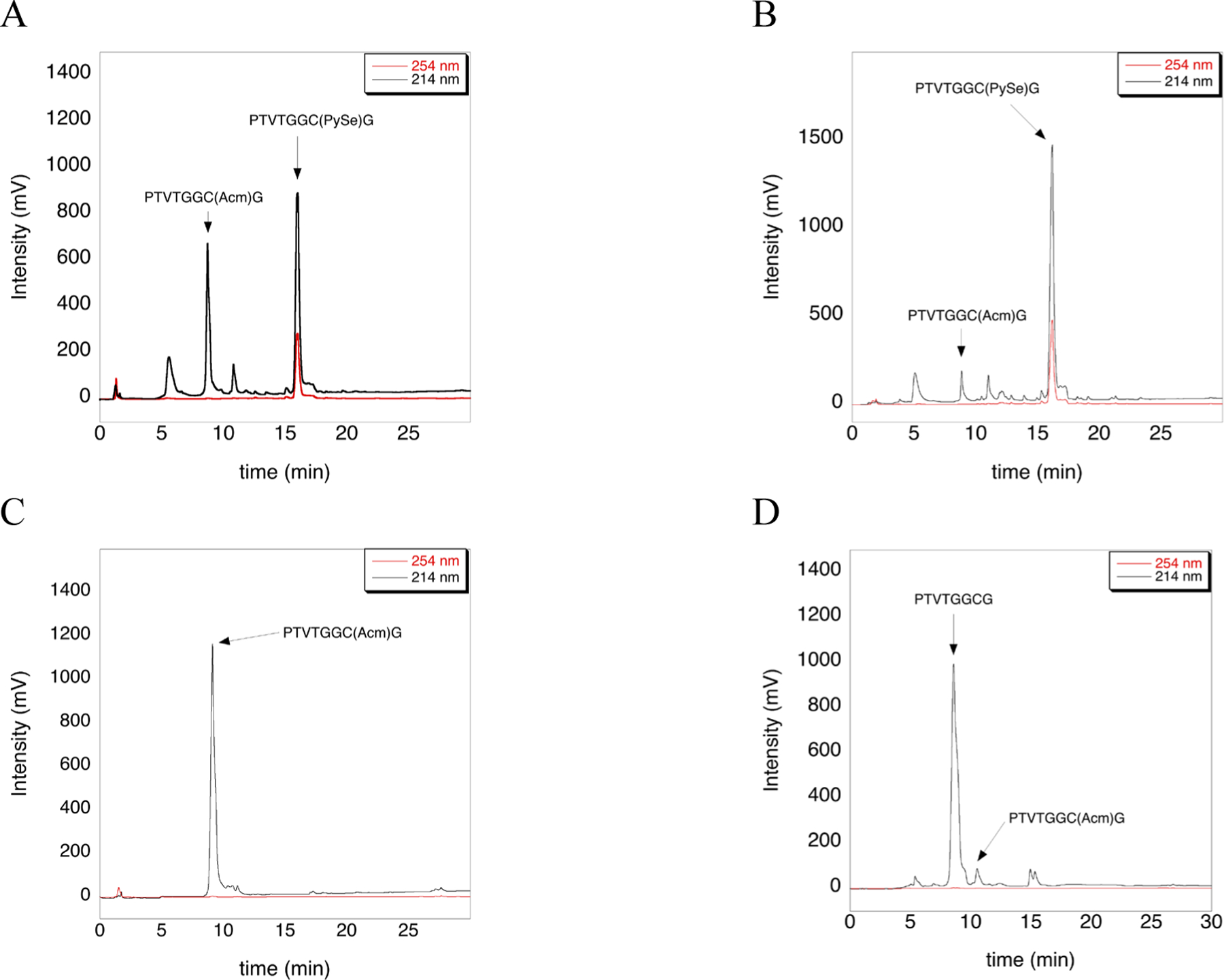

Figure 5: Deprotection of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide using PySeSePy and Asc determined by HPLC analysis.

A) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in neat TFA with 5-fold excess PySeSePy for 12 h at 37 °C. B) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in TFA/TIS (98:2) with 5-fold excess PySeSePy for 12 h at 37 °C. C) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in neat TFA for 12 h at 37 °C (control). D) HPLC chromatogram of the peptide containing the Cys(PySe) adduct treated with 5-fold excess ascorbate in 100 mM ammonium acetate pH 4.5, for 4 h at room temperature. The MS analysis that corresponds to each panel of Figure 5 is given in the Supporting Information as Figures S3.

TIS likely facilitates the deprotection of Cys(Acm) by PySeSePy by two different pathways. First, Cys(Acm) is partially deprotected by TIS to the free thiol which can then act as a nucleophile attacking the diselenide. Second, the protected S-atom of Cys(Acm) attacks the soft diselenide of PySeSePy in similar way as S-protected derivatives attack the soft disulfide bond of DTNP, resulting in deprotection.28 As before, we found that addition of Asc resulted in removal of the PySe-adduct (Figure 5D). The ability of the PySe to be easily reduced from Cys residues, resulting in a free thiol, will undoubtedly find utility in numerous applications including regioselective disulfide bond formation.

Because PySeSePy required slight heat (37 °C versus room temperature) in order for deprotection of both Cys(Mob) and Cys(Acm) to be complete, we decided to revisit the use of DTNP for the deprotection of Cys(Acm), as full deprotection was not achieved at ambient temperatures.29 We found that we were able to effect full deprotection of Cys(Acm) with a cocktail of 5 equivalents of DTNP dissolved in TFA/thioanisole (98:2) at 37 °C with a 12 h incubation time as shown by the HPLC analysis in Figure 6A and 6B. While the addition of TIS to the deprotection cocktail containing PySeSePy greatly enhanced the removal of Acm as shown by the results in Figure 5, addition of TIS to the cocktail containing DTNP resulted in breakdown of the Cys(5-Npys) adduct and the appearance of other unidentified products as shown by the HPLC chromatogram in Figure 6C. The breakdown of the Cys(5-Npys) adduct is most likely caused by reduction of this reactive disulfide bond by TIS. The identity of one of the side-products could be a TIS-(5-Npys) adduct.

Figure 6: Deprotection of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide using DTNP in the presence or absence of TIS determined by HPLC analysis.

A) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in neat TFA for 12 h at 37 °C (control). B) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in TFA/thioanisole (98:2) with 5-fold excess DTNP for 12 h at 37 °C. C) HPLC chromatogram of the Cys(Acm)-containing peptide incubated in TFA/thioanisole/TIS (96:2:2) with 5-fold excess DTNP for 12 h at 37 °C. The MS analysis that corresponds to panels 6A and 6B are given in the Supporting Information as Figure S4.

We note that we attempted to deprotect Cys(But), another popular S-protecting group, with PySeSePy, but we found the reaction to be ineffective. In our hands, we could only achieve less than 30% deprotection under the same conditions used to deprotect Cys(Acm).

Comparison of 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide with DTNP as a deprotection reagent.

Compared to DTNP, PySeSePy was not as effective as converting Cys(Mob) or Cys(Acm) to the corresponding pyridyl-adduct. For example, when our Cys(Mob)-containing peptide was treated with 5-fold excess PySeSePy for 4 h at room temperature in (96:2:2) TFA:TIS:water, about 45% of Cys(Mob) remained (Figure S5 of the Supporting Information). In contrast, nearly quantitative conversion of Cys(Mob) to Cys(5-Npys) was achieved when using 5-fold excess DTNP under the same conditions (Figure S6 of the Supporting Information). Similarly, PySeSePy was less effective at deprotecting Cys(Acm), which can be realized by directly comparing Figure 5B and 6B. Using similar conditions, 5%−10% of Cys(Acm) remained when using PySeSePy compared to when using DTNP in the deprotection cocktail.

There are two reasons for PySeSePy being less effective as a deprotection reagent compared to DTNP. First, the disulfide bond of DTNP is more electrophilic (“softer”) due to the presence of the p-nitro group on the aromatic ring. The p-nitro group polarizes the disulfide bond making it more reactive. Though we attempted synthesizing the p-nitro derivative of PySeSePy to increase its reactivity, attempts to obtain the compound in high yield and purity were unsuccessful. The second reason is that the redox potential of PySeSePy is much lower compared to DTNP, which means that diselenide bond formation is more favored compared to mixed disulfide bond formation.45 However, the advantage that PySeSePy has is that the mixed Cys-S–SePy adduct that is formed as a result of the deprotection reaction can be reduced by ascorbate in a chemoselective fashion, whereas the mixed Cys-S–S(5-Npys) adduct cannot.

Synthesis of guanylin using the 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide/ascorbate strategy.

Having showed that PySeSePy in combination with reduction by Asc was an effective method for removal of S-Mob and S-Acm protecting groups and resulting PySe-adduct, we next set out to demonstrate that this method could be used as part of an overall strategy for regioselective disulfide bond formation in a bioactive peptide containing multiple disulfide bonds. We chose the human intestinal peptide guanylin as our target.

Guanylin is a human hormone that regulates electrolyte and water transport in intestinal and renal epithelia.5,6 Guanylin is a 15-amino acid polypeptide that has two disulfide bonds. One between Cys4 and Cys12, and the second disulfide is between Cys7 and Cys15. Previously reported syntheses of guanylin utilized the Trt-group to protect Cys4 and Cys12, and Acm to protect Cys7 and Cys15.6,46 The first step of the synthesis utilized TFA to remove S-Trt groups, followed by air oxidation to form the first disulfide bond. Next, iodine oxidation was used to remove S-Acm from the second set of Cys residues, forming the second disulfide.6,46 However, iodine oxidation is cumbersome; the peptide must be dissolved in deoxygenated acetic acid/hydrochloric acid (4:1), resulting in a solution of pH 2, then incubated with 10–20 equivalents of iodine.6 Excess iodine is then reduced with sodium thiosulfate (or other quenching reagents such as activated charcoal or powdered zinc dust), and the peptide must be purified via HPLC.6,42 Such purification is necessary as iodine oxidation can result in disulfide bond scrambling,42,47 which leads to low yields of the desired peptide with correct disulfide pairing. Iodine oxidation can also modify oxidation-sensitive residues, such as methionine, tryptophan, and tyrosine.48–51 Rapid quenching of excess iodine after completion of the desired oxidation reaction can help to minimize the unwanted modification of Met, Trp, and Tyr.9, 42 However, these quenching reactions can result in undesired side products such as the formation of a peptide-thiosulfate adduct when sodium thiosulfate is used as the quenching reagent.52 Zhang and coworkers provide a detailed account of the cumbersome nature of working with iodine, and provide an alternative purification using ether precipitation.42

To improve the synthesis of guanylin without using iodine, we also synthesized guanylin with Cys4 and Cys12 with S-Trt protecting groups, and Cys7 and Cys15 with S-Acm protecting groups. During cleavage from the resin, both Trt protected Cys residues were converted to Cys-SH, and subsequent air oxidation provided the first disulfide bond (Figure 7A and 7B).

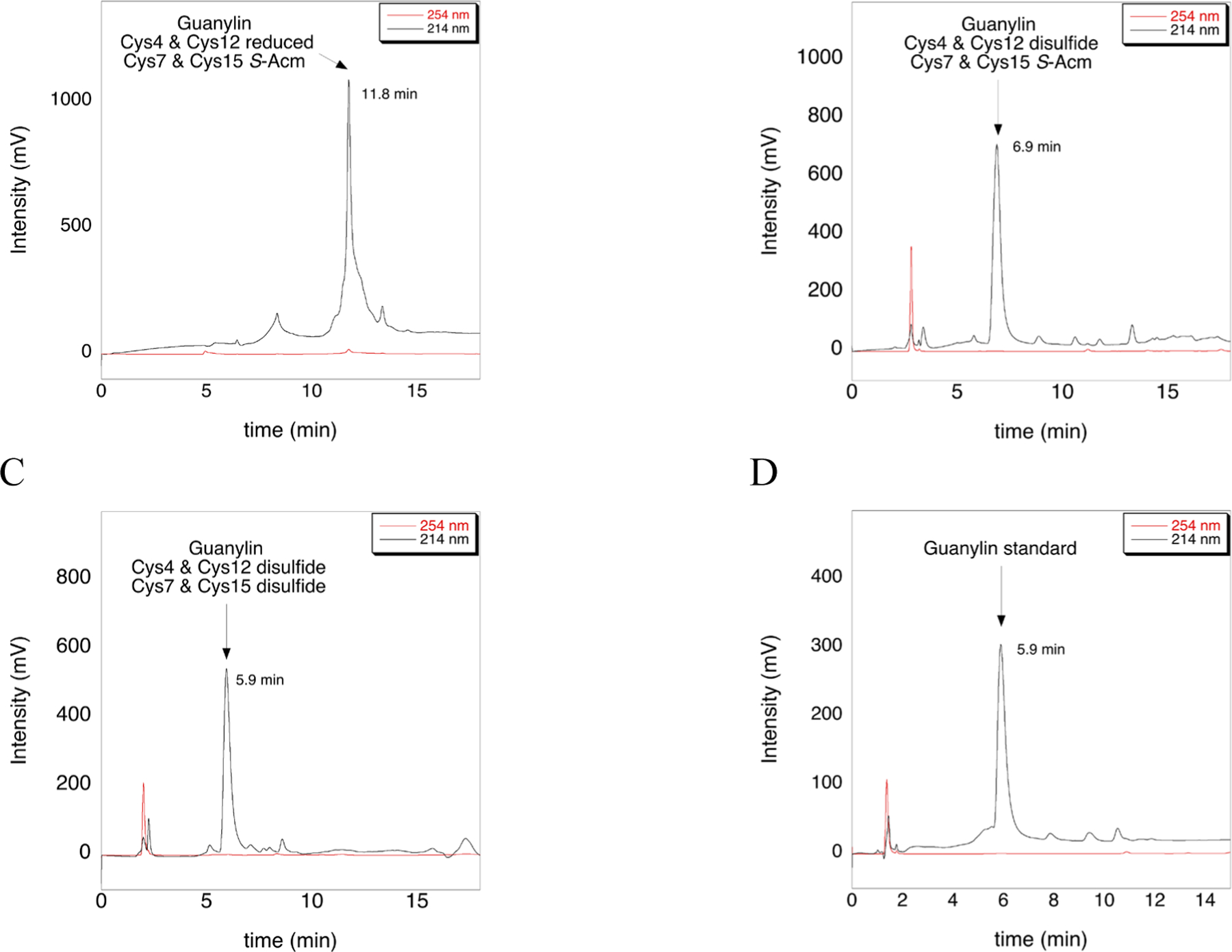

Figure 7: HPLC chromatograms of guanylin peptide at various stages of synthesis.

A) Crude guanylin peptide after cleavage from the resin with concomitant removal of S-Trt protecting groups. Cys4 and Cys12 are in the free thiol form, while Cys7 and Cys15 remain S-Acm protected. B) HPLC trace of the guanylin intermediate after the formation of the first disulfide bond between Cys4 and Cys12 using air oxidation. C) HPLC trace of the mature guanylin peptide after the formation of the second disulfide bond between Cys7 and Cys15 using 1 eq. of PySeSePy, incubated for 8 h at 37 °C. D) HPLC trace of the guanylin standard purchased from CPC Scientific. MS analysis that corresponds to Figure 7 can be found in the Supporting Information as Figure S7.

Our next step replaces the use of iodine with PySeSePy. We envisioned that we would form the second disulfide bond by first forming the Cys-S–Se-Py adduct, followed by addition of Asc to catalyze formation of the second disulfide without reduction of the first formed disulfide. However, we found that ascorbate reduction of the Cys-S–Se-Py adduct was not necessary. Instead, we found that when incubating guanylin with 1 equivalent of PySeSePy in 98:2 TFA:TIS for 8 h at 37 °C, the second disulfide bond formed spontaneously (Figure 7C). In this case, the propensity of PySeSePy to exist as the diselenide works in favor of disulfide bond formation. One can imagine that the two Cys-S–Se-Py adducts are close together in 3D-space in the partially folded peptide and that the two Se atoms spontaneously form a diselenide bridge with concomitant formation of the disulfide. This point is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Possible mechanisms for 2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide-mediated disulfide formation.

(A) Cys(PySe) adducts results after Acm removal with PySeSePy. Asc is a one-electron reducing agent53 that can reduce the Cys-S–SePy adduct, resulting in a Cys-thiolate and a PySe• radical. The ejected PySe• radical can then combine with another PySe• radical, reforming PySeSePy. The Cys-thiolate then undergoes SN2 attack onto the remaining Cys-S–SePy adduct to install the second disulfide bond. (B) An alternate mechanism has the PySe• radical formed after the reaction with Asc undergoing a SRN2 reaction54 with the remaining Cys-S–SePy adduct forming PySeSePy and a Cys-S• radical. The Cys-S• radical then can undergo a rapid radical recombination to form the second disulfide bond. (C) Experimentally, we found that disulfide bond formation was independent of the addition of Asc. In the partially folded intermediate, the two Cys(PySe) adducts are close together in 3D-space. We postulate that PySeSePy spontaneously forms as shown due to the low redox potential of the resulting diselenide.45 This thermodynamic driving force pushes disulfide bond formation to completion.

We confirmed the correct disulfide connectivity by HPLC (Figure 7C and 7D) by comparing our HPLC trace to that of commercially available guanylin. The peaks labelled in Figure 7 are confirmed by MS analysis (Figure S7 of the Supporting Information). Notably, there is a one-minute change in retention time between guanylin with only one disulfide bond formed (Figure 7B), and native guanylin with two disulfide bonds (Figure 7C and 7D). Thus, synthesis of guanylin was completed using orthogonal S-Trt and S-Acm groups, and PySeSePy to catalyze the formation of the second disulfide bond.

Test of Asc as a chemoselective reductant of selenosulfide bonds.

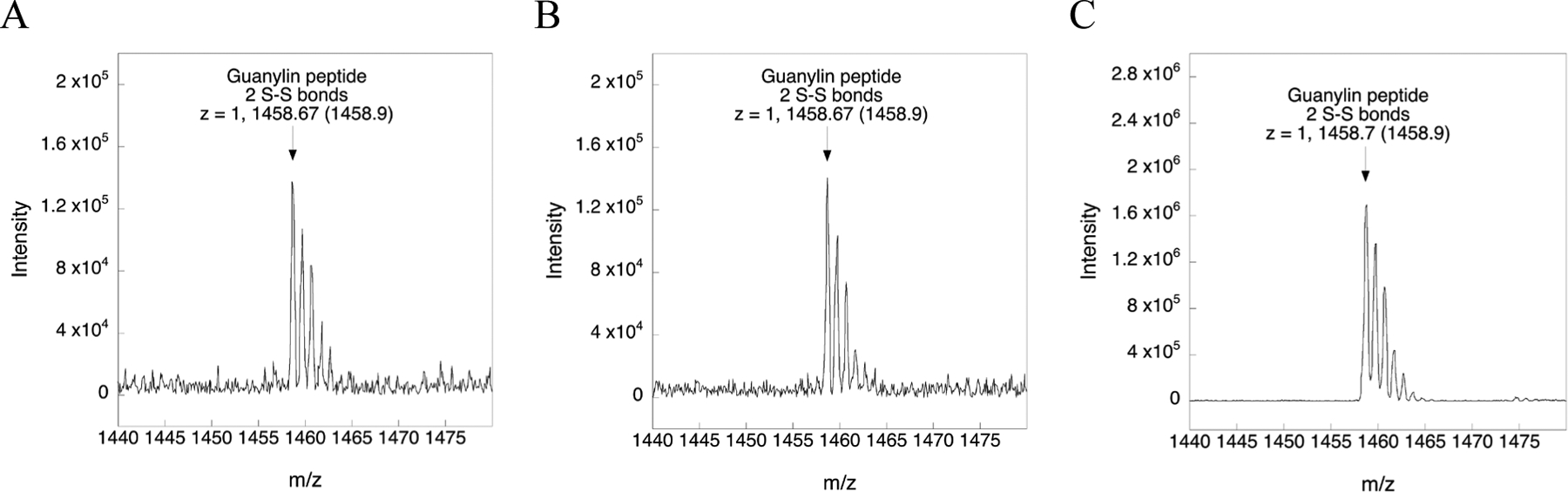

To show that Asc does not reduce disulfide bonds in the context of a folded peptide/protein under the acidic conditions used here to reduce a mixed Cys-S–SePy adduct, we tested whether 5-fold excess Asc would reduce guanylin at pH 4.5. Figure 9A–C shows the mass spectra of guanylin in buffer with or without 5-fold excess Asc at pH 4.5. Reduction should result in a gain of mass of either 2 or 4 daltons if Asc reduced one or both disulfide bonds of guanylin. The MS data in Figure 9 shows that 5-fold excess Asc does not reduce either disulfide bond at pH 4.5 after 4 h of incubation. Thus, Asc is a chemoselective reductant of Cys-S–SePy adducts.

Figure 9. Mass spectra of guanylin with and without Asc treatment at pH 4.5 for 4 h at room temperature.

A) Mass spectrum of the synthesized guanylin peptide incubated in 100 mM ammonium acetate at pH 4.5 without Asc (control). B) Mass spectrum of the synthesized guanylin peptide incubated in 100 mM ammonium acetate at pH 4.5 with 5-fold excess Asc. C) Mass spectrum of the commercially available guanylin peptide incubated in 100 mM ammonium acetate at pH 4.5 with 5-fold excess Asc. As is evident, there is no change in mass upon reduction with Asc under these conditions. For all samples, the arrow points to the observed m/z whereas the number inside the parentheses denotes the theoretical m/z value.

While PySeSePy has some significant advantages for regioselective disulfide bond formation as discovered here such as the use of Asc to chemoselectively reduce a selenosulfide bond and spontaneous disulfide bond formation from pairs of Cys-S–SePy adducts thermodynamically driven by formation of PySeSePy, we must note two disadvantages. First, PySeSePy is not commercially available and this will undoubtedly preclude its use for some users. We hope that PySeSePy will soon become commercially available, so as not to be a limiting factor. Second, like DTNP, PySeSePy remains as a contaminant in the peptide solution even after many washes with diethyl ether.

CONCLUSION

Herein, we report the use of PySeSePy as a new deprotection reagent for Cys(Acm) and Cys(Mob) residues after solid phase peptide synthesis. We found that upon incubation of these protected Cys residues with PySeSePy in TFA with scavengers for various lengths of time at 37 °C resulted in a stable Cys(PySe) adduct. This Cys(PySe) adduct was noticeably stable in TFA with TIS, while the Cys(5-Npys) that results from using DTNP is not. We also found that in the case of Cys(Acm), TIS scavenger is essential for deprotection using PySeSePy. In addition, the Cys(PySe) adduct can be chemoselectively reduced by Asc in buffer, as Asc is very slow to reduce unactivated disulfide bonds at pH 4.5. In addition, we show the utility of this new deprotection reagent for the regioselective formation of disulfide bonds in the synthesis of the human intestinal hormone guanylin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL141146 to RJH.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Acm

acetamidomethyl

- Ala or A

alanine

- Asc

ascorbate

- But

tert-butyl

- CDCl3

deuterated chloroform

- ESI

electron spray ionization

- Cys

cysteine

- Cys(5-Npys)

S-(2-thio(5-nitropyridyl))-L-cysteine

- Cys(PySe)

S-(selenopyridyl)-L-cysteine

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMF

N,N-dimethyl formamide

- DTNP

2,2’-dithiobis(5-nitropyridine)

- Fmoc

fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- Glu or E

glutamic acid

- Gly or G

glycine

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate

- HPLC

high pressure liquid chromatography

- Ile or I

isoleucine

- Mob

4-methoxybenzyl

- Mmt

methoxytrityl

- MS

mass spectrometry

- N2

nitrogen

- NMM

N-methyl morpholine

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- 5-Npys

2-thio(5-nitropyridyl)

- Pro or P

proline

- PySeSePy

2,2´-dipyridyl diselenide

- PySe

selenopyridyl

- rt

room temperature

- S

sulfur

- Se

selenium

- Sec or U

selenocysteine

- Sec(5-Npys)

Se-(2-thio(5-nitropyridyl))-L-selenocysteine

- SPPS

solid-phase peptide synthesis

- SBut

tert-butylmercapto

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- Thr or T

threonine

- TIS

triisoproprylsilane

- Tmp

2,4,6-trimethoxyphenylthio

- Trt

trityl

- Tyr or Y

tyrosine

- Val or V

valine

References

- 1.Chang SG, Choi KD, Jang SH & Shin HC Role of disulfide bonds in the structure and activity of human insulin. Mol cells. 2003;16(3):4117–4120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu F, Li P, Gelfanov V, Mayer J & DiMarchi R Synthetic advances in insulin-like peptides enable novel bioactivity. Acc. Chem. Res 2017;50(8):1855–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price-Carter M, Hull MS & Goldenberg DP Roles of individual disulfide bonds in the stability and folding of an ω-conotoxin. Biochemistry 1998;37(27):9851–9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehrmann J, Alewood PF & Craik DJ Structure determination of the three disulfide bond isomers of α-conotoxin GI: a model for the role of disulfide bonds in structural stability. J. Mol. Biol 1998;278(2):401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie MG, Fok KF, Kato J, Moore RJ, Hamra FK, Duffin KL & Smith CE Guanylin: an endogenous activator of intestinal guanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992;89:947–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klodt J, Kuhn M, Marx UC, Martin S, Rosch P, Forssmann W & Adermann K Synthesis, biological activity and isomerism of guanylate cyclase C‐activating peptides guanylin and uroguanylin. J. Pept. Res 1997;50:222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gongora-Benitez M, Tulla-Puche J & Albericio F Multifaceted roles of disulfide bonds. Peptides as therapeutics. Chem. Rev 2014;114(2):901–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shipolini R, Bradbyry AF, Callewaert GL, & Vernon CA The structure of apamin. Chem. Comm 1967;14:679–680. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreu D, Albericio F, Sole NA, Munson MC, Ferrer M & Barany G, in Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 35 Peptide Synthesis Protocols (Eds: Pennington MW and Dunn BM), Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ, 1994, Ch. 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aimoto S, Hojoh H, & Takasaki C Studies on the disulfide bridges of sarafotoxins. Chemical synthesis of sarafotoxin S6B and its homologue with different disulfide bridges. Biochemistry int. 1990; 21(6):1051–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craik DJ, Daly NL, Bond T, & Waine C Plant cyclotides: a unique family of cyclic and knotted proteins that defines the cyclic cystine knot structural motif. J. Mol. Biol 1999; 294(5):1327–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Göransson U, & Craik DJ Disulfide Mapping of the Cyclotide Kalata B1 Chemical Proof Of The Cyclic Cystine Knot Motif. J. Biol. Chem 2003;278(48):48188–48196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White SH, Wimley WC, & Selsted ME Structure, function, and membrane integration of defensins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 1995;5(4):521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsunemi M, Kato H, Nishiuchi Y, Kumagaye SI, & Sakakibara S Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of elafin, an elastase-specific inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm, 1992;185(3): 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XH, Connor M, Smith R, Maciejewski MW, Howden ME, Nicholson GM, … & King GF Discovery and characterization of a family of insecticidal neurotoxins with a rare vicinal disulfide bridge. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2000;7(6):505–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosengren KJ, Wilson D, Daly NL, Alewood PF, & Craik DJ Solution structures of the cis-and trans-Pro30 isomers of a novel 38-residue toxin from the venom of Hadronyche infensa sp. that contains a cystine-knot motif within its four disulfide bonds. Biochem., 2002;41(10):3294–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shabanpoor F, Hossain MA, Lin F & Wade JD Sequential formation of regioselective disulfide bonds in synthetic peptides with multiple disulfide bonds. Pept. Syn. App 2013;1047:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kudryavtseva EV, Sidorova MV & Evstigneeva RP Some peculiarities of synthesis of cysteine-containing peptides. Russ. Chem. Rev 1998;67:545–562. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moroder L & Musiol HJ Insulin‐a persistent synthetic challenge. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017;56(36):10656–10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulegue C, Musiol H-J, Prasad V & Moroder L Synthesis of cystine-rich peptides. Chim. Oggi 2006;24(4):24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moroder L, Musiol HJ, Götz M & Renner C Synthesis of single‐and multiple‐stranded cystine‐rich peptides. Biopolymers (Peptide Science). 2005;80:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moroder L, Besse D, Musiol HJ, Rudolph‐Böhner S & Siedler F Oxidative folding of cystine‐rich peptides vs regioselective cysteine pairing strategies. Biopolymers (Peptide Science) 1996;40:207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zervas L & Photaki I On cysteine and cystine peptides. I. New S-protecting groups for cysteine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1962;84(20):3887–3897. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlos K, Gatos D, Hatzi O, Koch N & Koutsogianni S Synthesis of the very acid‐sensitive Fmoc‐Cys (Mmt)‐OH and its application in solid‐phase peptide synthesis. Int. J. Protein Res 1996;47(3):148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houben Weyl Methods of Organic Chemistry Vol. E22a Synthesis of Peptides and Peptidomimetics (Goodman M, Felix Arthur, Moroder Luis, Toniolo Claudio, eds.) Thieme Stuttgart-New York, 2002, pp 384–413. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postma TM, Giraud M, & Albericio F Trimethoxyphenylthio as a Highly Labile Replacement for tert-Butylthio Cysteine Protection in Fmoc Solid Phase Synthesis. Org. Lett 2012;14(21):5468–5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ste.Marie EJ, Ruggles EL & Hondal RJ Removal of the 5‐nitro‐2‐pyridine‐sulfenyl protecting group from selenocysteine and cysteine by ascorbolysis. J. Pept. Sci 2016;22(9):571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris KM, Flemer S & Hondal RJ Studies on deprotection of cysteine and selenocysteine side‐chain protecting groups. J. Pept. Sci 2007;13(2), 81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroll AL, Hondal RJ & Flemer S Jr. 2,2’-Dithiobis(5-nitropyridine) (DTNP) as an effective and gentle deprotectant for common cysteine protecting groups. J. Pept. Sci 2012;18(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroll AL, Hondal RJ & Flemer S Jr The use of 2, 2′‐dithiobis (5‐nitropyridine)(DTNP) for deprotection and diselenide formation in protected selenocysteine‐containing peptides. J. Pept. Sci 2012;18(3):155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming JE, Bensch KG, Schreiber J & Lohmann W Notizen: Interaction of Ascorbic Acid with Disulfides. Z. Naturforsch 1983;38(9):859–861. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Colombo R, Milzani A & Rossi R Is ascorbate able to reduce disulfide bridges? A cautionary note. Nitric Oxide. 2008;19(3):252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P & Snyder SH Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat. Cell Biol 2001;3:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Keszler A, Broniowska KA & Hogg N Characterization and application of the biotin-switch assay for the identification of S-nitrosated proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2005;38(7):874–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forrester MT, Foster MW, Benhar M & Stamler JS Detection of protein S-nitrosylation with the biotin-switch technique. Free Radic. Biol. Med 2009;46(2):119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown HC, Nazer B & Cha JS Selective reduction of disulfides to thiols with potassium triisopropoxyborohydride. 1984. Dissertation. Perdue University, Lafayette, IN. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnamurthy S & Aimino D Rapid and selective reduction of functionalized aromatic disulfides with lithium tri-tert-butoxyaluminohydride. A remarkable steric and electronic control. Comparison of various hydride reagents. J. Org. Chem 1989;54:4458–4462. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser E, Colescott RL, Bossinger CD & Cook PI Color test for detection of free terminal amino groups in the solid-phase synthesis of peptides. Anal. Biochem 1970;34(2):595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun T, Jin Y, Qi R, Peng S & Fan B Post‐assembly of oxidation‐responsive amphiphilic triblock polymer containing a single diselenide. Macromol. Chem. Phys 2013;214(24):2875–2881. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamber B, Hartmann A, Eisler K, Riniker B, Rink H, Sieber P, & Rittel W The synthesis of cystine peptides by iodine oxidation of S‐trityl‐cysteine and S‐acetamidomethyl‐cysteine peptides. Helvetica Chimica Acta 1980;63(4):899–915. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veber D, Milkowski J,Varga S, Denkewalter R & Hirschmann R Acetamidomethyl. A novel thiol protecting group for cysteine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972;94(15):5456–5461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Lin F, Hossain MA, Shabanpoor F, Tregear GW & Wade JD Simultaneous post-cysteine (S-Acm) group removal quenching of iodine and isolation of peptide by one step ether precipitation. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther 2008;14(4):301–305. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ste. Marie EJ & Hondal RJ Reduction of cysteine‐S‐protecting groups by triisopropylsilane. J. Pept. Sci 2018;24(11), e3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenny KA, Ste. Marie EJ, Mose G, Ruggles EL & Hondal RJ Facile removal of 4‐methoxybenzyl protecting group from selenocysteine. J. Pept. Sci 2019:e3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Besse D, Siedler F, Diercks T, Kessler H & Moroder L The redox potential of selenocystine in unconstrained cyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1997;36(8)883–885. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauber T, Neudecker P, Rösch P & Marx UC Solution Structure of Human Proguanylin the role of a hormone prosequence. J. Biol. Chem 2003;278:24118–24124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hargittai B & Barany G Controlled syntheses of natural and disulfide‐mispaired regioisomers of α‐conotoxin SI. J. Peptide Res 1999;54(6):468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu F, Liu Q & Mezo AR An iodine-free and directed-disulfide-bond-forming route to insulin analogues. Org. Lett 2014;16(11):3126–3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sieber P, Kamber B, Riniker B & Rittel W Iodine Oxidation of S‐Trityl‐and S‐Acetamidomethyl‐cysteine‐peptides Containing Tryptophan: Conditions Leading to the Formation of Tryptophan‐2‐thioethers. Helv. Chim. Acta 1980;63(8):2358–2363. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamthanh H, Roumestand C, Deprun C & Menez A Side reaction during the deprotection of (S‐acetamidomethyl) cysteine in a peptide with a high serine and threonine content. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res 1993;41(1):85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Engebretsen M, Agner E, Sandosham J & Fischer PM Unexpected lability of cysteine acetamidomethyl thiol protecting group Tyrosine ring alkylation and disulfide bond formation upon acidolysis. J. Peptide Res 1997;49(4):341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kudryavtseva E, Sidorova M, Ovchinnikov M, Bespalova ZD & Bushuev V Comparative evaluation of different methods for disulfide bond formation in synthesis of the HIV‐2 antigenic determinant. Peptide Res.1997;49:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iyanagi T, Yamazaki I, & Anan KF One-electron oxidation-reduction properties of ascorbic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1985;806(2): 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rossi RA, & Palacios SM On the SRN1-SRN2 mechanistic possibilities. Tetrahedron, 1993;49(21): 4485–4494. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.