Context

South Africa is a large country (1.2 m km2) ranging from temperate to sub-tropical climatic conditions with large semi-arid areas. Population in 2020 is estimated at 59.62 million (51.1% female) with 5.4 million (9.1%) older than 60 years and 17.1 million (28.6%) younger than 15 years [1]. 39.6 million (66.7%) of the population is urban [2]. Approximately one in seven households (in urban areas, one in five) is in an informal settlement, and overcrowding is common [3]. Slightly over one third of South African households lacks access to a reliable water supply, and 14.1 million persons lack access to safe sanitation [4]. The country is home to 3.9 million migrants (70% from other African countries) [5], with most of these accumulating in the provinces of Gauteng (1.5 million estimated immigrants in 2020) and Western Cape (470,000) [1].

Life expectancy at birth is estimated at 62.5 years for males and 68.5 years for females [1] and median age is 27.6 [2]. An estimated 7.8 million people are living with HIV in 2020. HIV prevalence is estimated at 13% of total population, and 19% in age range 18–49 [1]. Tuberculosis is the leading overall cause of death, followed by diabetes mellitus (leading for females) [6].

Although it is a higher-middle income country, South African society stands out as one of the most unequal in the world [7]. In 2017 it was estimated that around 30.5 million people (55% of the population) lived below the Upper Bound Poverty Line [8]. The economy contracted two consecutive quarters in the last half of 2019 [9] and unemployment in the last quarter of 2019 was 29% (26% among males, 31% among females) [10]. The informal sector accounts for slightly over one third of the workforce [10]. The country is food secure at a national level but not at the household level, with individual and household food security relying predominately upon income [11].

Prior to COVID-19, South Africa had 7200 critical care beds, 3500 intensive care beds, and 2700 high care beds, out of a total of 100,000 hospital beds overall, with 75% occupancy [12]. However, provincial differences exist [13]. South Africa has a public healthcare system aiming at universal coverage but in practice there are significant challenges meeting demand, and individuals who can afford private health insurance commonly do, with larger employers (such as the authors') commonly making this mandatory.

Shape of the epidemic

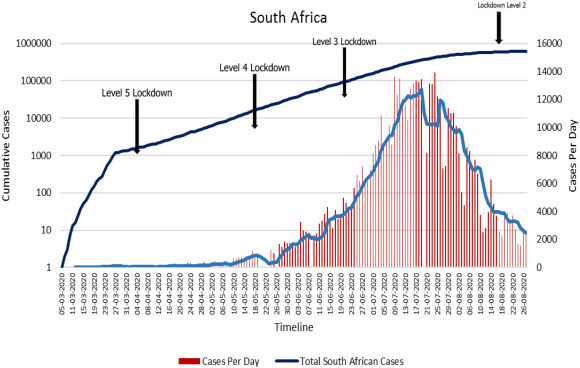

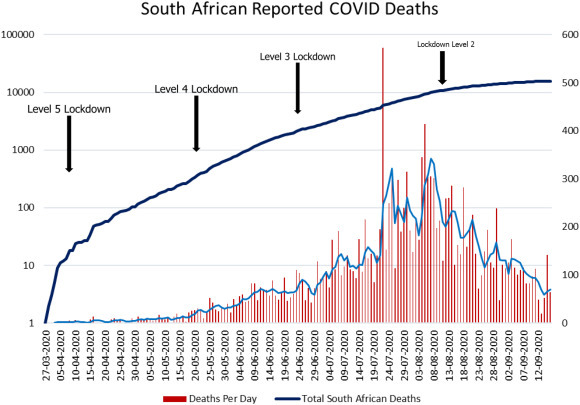

The first case was reported in South Africa on 5 March. Deaths due to COVID-19 have yet to be published in the registration of deaths system but have been reported weekly by the South African Medical Research Council, limited to those with a valid South African identity document and aged more than one year [1]. The first reported death attributed to COVID-19 occurred on 27 March. At the national level, growth was remarkably constant between the end of March and the peak in mid-late July.

Deaths follow a similar trend to cases, with a time lag (see Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Total deaths stand at 15,772 as of official government update of 17 September [14].

Fig. 1.

Cases.

Fig. 2.

Deaths.

Response

The South African government responded early, enacting a State of Disaster on 15 March [15]. Initial restrictions were moderate (restrictions on bars and restaurants, tourism, travel) but from 27 March a full lockdown was implemented prohibiting leaving the home for any non-essential purpose (including exercise) and providing a restrictive list of essential activities, shutting down most economic activity. The response was subsequently categorized by level, with 5 being the most severe. Transitions to levels 4, 3, 2, and 1 occurred on 1 May, 13 July, 19 August and 21 September respectively. Level 1 has been called a “new normal” that is likely to persist for the foreseeable future, permitting international travel and many activities but with restrictions (e.g. bar capacities limited to 50%) and including a four-hour nightly curfew (12–4 am).

Data is not available on the response of the healthcare system. The Minister of Health made a statement on the intention to add beds during the peak phase of the pandemic [16] but we have not been able to access any relevant data (see Discussion). Testing was implemented in both targeted and randomized forms, with a total of 3,983,533 tests to date.

On 24 April the government announced a stimulus package of 500 billion South African Rands, currently around 30 million US Dollars.

| Measure | ZAR billion |

|---|---|

| Credit Guarantee Scheme | 200 |

| Job creation | 100 |

| Income support | 70 |

| Vulnerable households | 50 |

| Wage protection (UIF) | 40 |

| Health and frontline services | 20 |

| Municipalities | 20 |

| Total | 500 |

Discussion

South Africa is unique in many ways, and conscious of being so. It is striking, therefore, how little consideration was given to the specifics of its circumstances by the South African response strategy. The youth of the population would tend to make it less susceptible to lethal COVID-19; poverty and insecure income would tend to make it more susceptible to health impacts of economic hardship; and overcrowded living conditions with inadequate sanitation would significantly modify both the effectiveness of a given regulatory measure at achieving reduction in social contact and the feasibility of implementing such a measure. Locking down with 10 other people in a small dwelling 200 m from the nearest ablutions is both less effective and less pleasant than doing so in a suburban house occupied by a single family. 18.7 million people (roughly 30% of the population) rely on social grants [17] and thus need to travel and queue to receive these grants, and non-grant relief measures (e.g. food parcels) also commonly involve queuing.

These factors may explain the apparent unresponsiveness of the epidemic to the lockdown regulations. Contrary to widespread political and popular views, no changes in the shape of the curve can be attributed to the introduction or easing of any regulation at this stage.

The first change in trajectory (viewed on a logarithmic scale) was a sharp easing off that took place at the time lockdown was introduced (see Fig. 1), and cannot therefore be attributed to lockdown, although it could potentially be attributed to the initial measures introduced on 15 March (we do not say that it is attributable, only that this is a theoretical possibility).

The second change is a gradual easing that began in the later part of July, well into Alert Level 3, a significantly eased regulatory scenario. There are no further changes in the trajectory of the curve; no changes can be attributed to lockdown regulations simply because there are no such changes to attribute.

This does not show that locking down made no difference relative to a counterfactual scenario (and a full analysis would need to consider provincial trajectories too), but it does mean that a detailed (and provincial) analysis needs to be undertaken before we can evaluate the effectiveness of lockdown measures in the South African context. Were we to try to “read off” the effect of the interventions from the shape of the epidemic, we would have to conclude they had no effect. Likewise we would have to attribute the slow progress of the epidemic in the country to background features (e.g. the relative youthfulness of the population). This is a caution against such “reading off” both in this context and others.

The connections between public health and politics, both local and global, cannot be ignored in this pandemic. The government's initial actions against COVID-19 were internationally praised as decisive and brave. However, neither the interventions nor the praise were informed by local data, locally parameterized models, local epidemiological expertise, or qualitative local knowledge. One might speculate that the country's non-democratic history partly explains the ease with which it moved to a stringent lockdown. One might also speculate that there was a political need to display strong leadership internally and to look good internationally.

Whatever the reason for locking down, it was not clearly articulated, and this created difficulties after the initial praise was over, because the government was unable to communicate the rationale for its ongoing actions. Initial decisiveness gave way to a lengthy paralysis during which communication was confusing, with different ministers saying different things. Little action appeared to be taken except by the police and army, who enforced lockdown over-enthusiastically [18]. As time passed, the content of the regulations was increasingly questioned in media and on social media, especially because sale of tobacco and alcohol were restricted. The evidence base for such restrictions was contrasted unfavorably with evidence of political influence of illegal trade interests.

It was and remains far from clear what difference the lockdown made to the preparedness of the healthcare system: as noted above, data is simply not available. The hospitals were in fact overwhelmed [19], but then the tide turned anyway. It is simply impossible to tell at present what difference if any was made either by the regulations that were put in place or by diversions of resources within or to the healthcare system. Testing is perhaps the strongest point of the healthcare response, but even here, over half of the four million tests conducted have been private [14].

The substantial stimulus package has also fallen short in its initial implementation, with food parcels being diverted by corrupt local government officials [20], and system failures making the collection of grants difficult even months after their introduction [21]. There was also some backpedaling in respect of certain grants, notably the top-up to the Child Support Grant being adjusted to apply per caregiver and not per child. These failings have obvious potential for health impact.

The indirect health impact of COVID-19 is so far hard to assess. Despite efforts, we have been unsuccessful in obtaining causes of death data from the South African authorities. There are anecdotes from frontline medical workers of an increase in malnutrition cases but without the cooperation of the state, analysis is difficult; and senior scientists have been attacked by politicians for expressing views about indirect health impacts [22].

Nonetheless, given the context, it is reasonable to anticipate the following increased health burdens in coming months:

-

•

Increase in incidence of malnutrition, especially among children (who did not benefit from the school feeding programme during lockdown);

-

•

increases in mortality due to HIV and TB as a consequence of disruption of treatment programmes;

-

•

disruption to vaccination programmes with possible associated disease outbreaks;

-

•

disruption to maternal and infant care resulting in increased mother and infant mortality;

-

•

disruption to cancer treatment and surgery;

-

•

outbreak of infectious diseases associated with poverty, malnutrition, and disruption of vaccination; and

-

•

reduced life expectancy at birth as a consequence of all of the above.

As part of an ongoing project we are attempting to test these hypotheses against empirically based projections.

From the perspective of a global epidemiology, this is a reminder of the historical connections between the disciplines of epidemiology and statistics, and the organization of the state: epidemiology became possible with reliable state records, and “state” is the root of the word “statistics”. States unable or unwilling to maintain accurate public health records cannot benefit from local epidemiology and will be forced to rely on imported models for projection and policy. The international epidemiological community can, for its part, be aware of the vast contextual differences between nations, and remember that interventions may be differentially appropriate or effective. The importance of understanding the social context before recommending an intervention is already well-established by regional experiences of HIV [23].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

Research supported by the Center for Global Development (Europe), London, UK.

References

- 1.Statistics South Africa . 2020. Mid-year population estimates 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Worldometer South Africa population (2020) 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/south-africa-population/ [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 16-Sep-2020)

- 3.Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI) 2018. Informal Settlements and Human Rights in South Africa: submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living. [Google Scholar]

- 4.South African Government Department of Water and Sanitation . 2018. National water and sanitation master plan. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Migration Data Portal Migration data portal | South Africa. 2020. https://migrationdataportal.org/?i=stock_abs_&t=2019&cm49=710 [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 11-Jun-2020)

- 6.Statistics South Africa . 2020. Mortality and causes of death in South Africa, 2016: findings from death notification. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IMF . 2020. Staff report for the 2019 article IV consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics South Africa . 2017. Poverty trends in South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics South Africa . 2020. Gross domestic product - fourth quarter 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistics South Africa . 2019. Quarterly labour force survey - quarter 4, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics South Africa . 2019. Towards measuring the extent of food security in South Africa: an examination of hunger and food inadequacy. [Google Scholar]

- 12.South Africa COVID-19 Modelling Consortium . May 2020. Estimating cases for COVID-19 in South Africa - long-term national projections. [Google Scholar]

- 13.South African COVID-19 Modelling Consortium . May 2020. Estimating cases for COVID-19 in South Africa - long-term provincial projections. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mkhize Z. Update on Covid-19 (17th September 2020) - SA Corona virus online portal. SA Coronavirus. 17-Sep-2020. https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2020/09/17/update-on-covid-19-17th-september-2020/ [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 18-Sep-2020)

- 15.South African Government . 18-Mar-2020. Regulations issued in terms of Section 27(2) of the Disaster Management Act 2002. Government Gazette South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 16.SA Coronavirus Online Portal Increasing bed capacity in the midst of the COVID-19 peak. 10-Jul-2020. https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2020/07/10/increasing-bed-capacity-in-the-midst-of-the-covid-19-peak/ [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 18-Sep-2020)

- 17.National Treasury South Africa . 2019. Estimates of National Expenditure 2019 Abridged version. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts K., Broadbent A., Smart B. The Conversation; 15-Apr-2020. Why heavy-handed policing won’t work for lockdowns in highly unequal countries.https://theconversation.com/why-heavy-handed-policing-wont-work-for-lockdowns-in-highly-unequal-countries-135989 [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 18-Sep-2020) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding A. Coronavirus in South Africa: inside Port Elizabeth's hospitals of horrors BBC News. 14-Jul-2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-53396057 [Online]. Available:

- 20.Mahlangu T. Government to tackle food parcel corruption - corruption watch. 24-Apr-2020. https://www.corruptionwatch.org.za/government-to-tackle-food-parcel-corruption/ [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 18-Sep-2020)

- 21.Mlamla S. South Africans in struggle to get Sassa Covid-19 relief grants, Cape Argus. 02-Sep-2020. https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/south-africans-in-struggle-to-get-sassa-covid-19-relief-grants-470d80c9-897d-4f1f-ab2d-cef3c5497e8a [Online]. Available:

- 22.Pitjeng R. Eyewitness News; 27-May-2020. What happened with Glenda Gray? A timeline.https://ewn.co.za/2020/05/27/what-happened-with-glenda-gray-timeline [Online]. Available: (Accessed: 18-Sep-2020) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdool Karim Q. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]