Abstract

Objectives

Tocilizumab has been proposed as a candidate therapy for patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), especially among those with higher systemic inflammation. We investigated the association between receipt of tocilizumab and mortality in a large cohort of hospitalized patients.

Methods

In this cohort study of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Spain, the primary outcome was time to death and the secondary outcome time to intensive care unit (ICU) admission or death. We used inverse probability weighting to fit marginal structural models adjusted for time-varying covariates to determine the causal relationship between receipt of tocilizumab and outcome.

Results

Data from 1229 patients were analysed, with 261 patients (61 deaths) in the tocilizumab group and 969 patients (120 deaths) in the control group. In the adjusted marginal structural models, a significant interaction between receipt of tocilizumab and high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels was detected. Tocilizumab was associated with decreased risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.34, 95% confidence interval 0.16–0.72, p 0.005) and ICU admission or death (adjusted hazard ratio 0.39, 95% confidence interval 0.19–0.80, p 0.011) among patients with baseline CRP >150 mg/L but not among those with CRP ≤150 mg/L. Exploratory subgroup analyses yielded point estimates that were consistent with these findings.

Conclusions

In this large observational study, tocilizumab was associated with a lower risk of death or ICU admission or death in patients with higher CRP levels. While the results of ongoing clinical trials of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 will be important to establish its safety and efficacy, our findings have implications for the design of future clinical trials.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, COVID-19, Mortality, SARS-CoV-2, Tocilizumab

Introduction

There are still no treatments with proven efficacy to prevent mortality in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia, with the exception of corticosteroids in selected patient groups [1]. However, various medications such as hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin and lopinavir/ritonavir have been prescribed on an off-label basis worldwide [2]. Tocilizumab is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved humanized monoclonal antibody against the soluble interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor. It is widely used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis or cytokine release syndrome [3,4]. IL-6 determination is rarely available in clinical settings. However, CRP—an inflammatory biomarker upstream in the IL-6 pathway—is commonly used to monitor the activity of inflammatory diseases [5].

Tocilizumab has been suggested as an effective treatment for severe COVID-19 pneumonia due to the increased IL-6 blood levels in patients with COVID-19 [6] and its correlation with more severe lung damage [7]; however, it is not currently approved for use by any regulatory body in COVID-19 patients.

To date, very few efficacy results from clinical trials in this disease have been published [1]. Available data on the use of tocilizumab come from retrospective observational studies with confounding factors [8] or from small studies with surrogate endpoints that are underpowered to detect significant clinical effects or lack a control group [[9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. There are currently ongoing clinical trials with both tocilizumab and sarilumab, but the results have not yet been published (NCT04320615 and NCT04315298).

We investigated the association between receipt of tocilizumab and mortality in a large cohort of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Spain. We hypothesized that receipt of tocilizumab would be associated with a lower risk of death and influenced by baseline systemic inflammation levels. We used marginal structural modeling to account for baseline and time-varying confounders.

Methods

Study design, setting and data sources

We analysed data from 2047 patients included in the HM Hospitales cohort, which comprised a multicentre cohort of people admitted to any of the 17 hospitals in the HM Group in Spain diagnosed with COVID-19 from 31 January to 23 April 2020. HM Hospitales made their anonymous data set freely accessible to the international medical and scientific community [14]. The data set includes comprehensive clinical information on patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, confirmed by PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs or other respiratory specimens. The data set collects the different interactions in the COVID-19 treatment process, including detailed information on diagnoses, treatments, admissions, ICU admissions, diagnostic imaging tests, laboratory results, discharge or death. It includes more than 60 000 drug records, 54 000 vital sign records and more than 398 000 laboratory records, which include all the requests made to each patient during admission and in the previous emergency, if any. Moreover, more than 1900 diagnostic and procedural records are collected and coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) classification [15].

We excluded patients younger than 18 years and those who died or were transferred to another facility within 24 hours after admission to the emergency department. This study was approved by the ethics committee at University Hospital Ramón y Cajal (approval 191/20).

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the time from study baseline (defined as the first day of hospitalization) to in-hospital death for any cause. The secondary outcome was a composite event including admission to the ICU or death (hereafter ICU/death). Patients were censored at the endpoint or at the end of follow-up (hospital discharge or end of data collection in the database).

Statistical analysis

We tested the associations among the preadmission variables with treatment variable by chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. We calculated the crude incidence rates of death and ICU/death using Kaplan-Meier methods. We fitted marginal structural models to estimate discrete time hazards of death according to receipt of tocilizumab via an inverse probability treatment weight (IPTW) estimation to account for the nonrandomized treatment administration of tocilizumab, baseline confounding and time-varying confounders, with the aim of minimizing the indication bias [16,17].

We assumed that once patients received tocilizumab, they continued to be prescribed it until the end of follow-up. This assumption helped obtain a conservative estimate of the treatment hazard ratio (HR) analogous to intention-to-treat analysis in an unblinded randomized controlled trial. We structured the data set to allow for time-dependent covariates to change daily after admission. Propensity score logistic models predicted exposure at baseline and censoring over time as a result of recognized confounders of severe COVID-19 [18,19]. Weighted HRs derived from marginal structural models were adjusted for age, gender, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, kidney disease, congestive heart failure, lung disease), oxygen blood saturation and need for oxygen therapy at baseline and time-varying parameters of clinical severity (blood pressure, heart rate, total lymphocyte and neutrophil count, lactate dehydrogenase, alanine aminotransferase, urea, d-dimers, CRP) that could be affected by treatment exposure.

There were 1229 patients in the data set with the information needed to fit marginal structural models. The characteristics of the individuals not included as a result of missing data required for the statistical modeling strategy are shown in the Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The main differences between groups in the analysed population were comparable to those found in the population with missing information. IPTW were stabilized and truncated below the first percentile and above the 99th percentile. The models included a main term for the exposure and a flexible functional form of time, that is, restricted cubic splines with 5 knots set at the first, 25th, 50th, 75th and 99th percentiles of the subject's day of follow-up and the interaction term between tocilizumab and elevated CRP levels (>150 mg/L, with the cutoff selected on the basis of the 75th percentile value, 143 mg/L). The interaction term between tocilizumab and CRP was significant; we thus report the adjusted (weighted) HRs derived from marginal structural models for the primary and secondary outcomes segregated by CRP levels.

We planned exploratory sensitivity analyses restricted to patients who received specific concomitant treatments against SARS-CoV-2. As a result of the recognized prognostic value of lymphocyte counts and d-dimer levels, we also performed sensitivity analyses to explore the possible confounding effect of d-dimer >1000 ng/mL (upper limit of the normal range in our reference laboratory) or absolute lymphocyte count <1000/μL (lower limit of the normal range in our reference laboratory). Statistical analyses were performed by Stata 16.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study population

We analysed 1229 patients accounting for 10 673 person-days of follow-up who were diagnosed with COVID-19 in HM Hospitales between 31 January and 23 April 2020 and had the information needed for IPTW estimation. We excluded 99 patients because they had died, were discharged or were transferred to a different hospital within 24 hours after admission to the emergency department (Supplementary Fig. S1). A total of 181 patients (14.7%) died, 82 (6.7%) were admitted to the ICU and 186 (15.1%) had a composite outcome of death or ICU admission. Of the total number of deceased patients, 22 (12%) were admitted to the ICU and 159 (88%) were not admitted.

Of the 1229 patients, 260 (21%) received a median (interquartile range, IQR) total dose of 600 (600–800) mg of tocilizumab. The first dose was administered at a median (IQR) time of 4 (3–5) days from inpatient admission. The median (IQR) time to censoring date was 13 (10–17) days for the tocilizumab group and 8 (5–10) days for the control group. The distribution of patient characteristics as well as mortality and ICU admission rates according to receipt of tocilizumab are shown in Table 1 . Compared to the control group, there was a higher frequency of men and previous lung disease in the tocilizumab group, while controls were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of diabetes. As expected, there were small differences between both groups in some of the baseline vital signs and laboratory parameters that were indicative of greater disease severity in the tocilizumab group than in the control group.

Table 1.

Population baseline characteristics according to receipt of tocilizumab

| Characteristic | No tocilizumab (n = 969) | Tocilizumab (n = 260) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 (57–80) | 65 (55–76) | 0.017 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 574 (59) | 191 (73) | <0.001 |

| Female | 395 (41) | 69 (27) | |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension | 227 (23) | 44 (17) | 0.025 |

| Diabetes | 233 (24) | 47 (18) | 0.042 |

| Congestive heart failure | 31 (3) | 5 (2) | 0.279 |

| Coronary artery disease | 77 (8) | 21 (8) | 0.945 |

| Chronic kidney Disease | 53 (5) | 11 (4) | 0.425 |

| Chronic lung disease | 94 (10) | 39 (15) | 0.015 |

| Dementia | 40 (4) | 2 (1) | 0.008 |

| Vital signs at admission | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 83 (72–94) | 84 (75–96) | 0.059 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 127 (114–140) | 128 (115–141) | 0.592 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.5 (36.0–37.1) | 36.8 (36.1–37.4) | 0.003 |

| Peripheral oxygen saturation (%) | 94 (92–96) | 91 (86–94) | <0.001 |

| Needing supplemental oxygen | 241 (25) | 54 (21) | 0.169 |

| Baseline laboratory | |||

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/mm³) | 1050 (770–1440) | 890 (630–1225) | <0.001 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/mm³) | 4670 (3350–6560) | 5425 (3710–8165) | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 523 (408–664) | 669 (566–829) | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 26 (16–45) | 32 (21–53) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.081 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 33 (25–48) | 22 (26–46) | 0.957 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 64 (27–122) | 113 (64–220) | <0.001 |

| d-Dimer (ng/mL) | 720 (443–1389) | 809 (519–1270) | 0.127 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/mL) | 27 (7–60) | 70 (26–182) | <0.001 |

| Outcome | |||

| Non-ICU length of stay (days) | 8 (5–10) | 13 (10–18) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 32 (3) | 50 (19) | <0.001 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 2 (1–3) | 6 (2–11) | 0.002 |

| Overall mortality | 120 (12) | 61 (23) | <0.001 |

| ICU mortality | 6 (19) | 16 (32) | 0.187 |

| Non-ICU mortality | 114 (12) | 45 (21) | <0.001 |

| ICU or mortality | 146 (15) | 95 (37) | <0.001 |

| Coadministration of other agents | |||

| Corticosteroids | 340 (35) | 242 (93) | <0.001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 877 (91) | 257 (99) | <0.001 |

| Azithromycin | 615 (63) | 197 (76) | <0.001 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 533 (55) | 220 (85) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (IQR). All variables were available in 1229 subjects except interleukin 6, which was measured in 88 individuals.

ALT, aspartate alanine transferase; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Primary and secondary endpoints

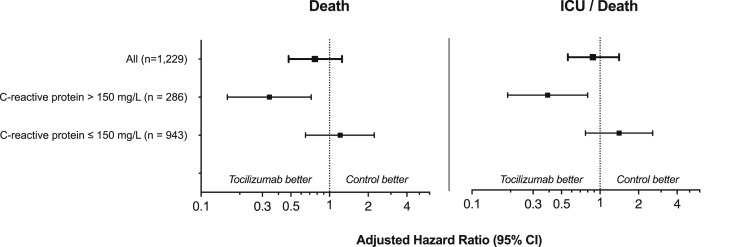

The 1229 subjects accounted for 11 900 observations; the crude incidence rate of death was 17.8 (95% confidence interval (CI) 13.8–22.8) per 1000 persons-days in the tocilizumab group vs. 16.6 (95% CI 13.9–19.8) per 1000 persons-days in the control group. In the unadjusted analysis (logistic regression analysis with no covariates entered into the model), tocilizumab was associated with a higher risk of death (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.20–1.96, p 0.001) and ICU/death (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.41–2.22, p < 0.001). However, this effect disappeared in the adjusted analyses, in which we found a significant interaction between receipt of tocilizumab and CRP values (p 0.023 and 0.012 for primary and secondary endpoints respectively). Patients who received tocilizumab and had baseline CRP levels above 150 mg/L experienced lower rates of death (adjusted HR (aHR) 0.34, 95% CI 0.17–0.71, p 0.005) and ICU/death (aHR 0.39, 95% CI 0.19–0.80, p 0.011) than those who did not receive tocilizumab. This effect was not observed among patients with baseline CRP levels ≤150 mg/L (aHR 1.21, 95% CI 0.65–2.23 in the primary outcome and aHR 1.41, 95% CI 0.77–2.58 in the secondary outcome) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios for primary and secondary endpoints. Weighted hazard ratios derived from marginal structural models adjusted for sex, age, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, lung disease), need for oxygen therapy at baseline, oxygen blood saturation and time-varying parameters of severity (blood pressure, heart rate, total lymphocyte and neutrophil count, LDH, ALT, urea, d-dimer and CRP). The p values for interaction between receipt of tocilizumab and CRP values were 0.023 and 0.012 for primary and secondary endpoints respectively. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

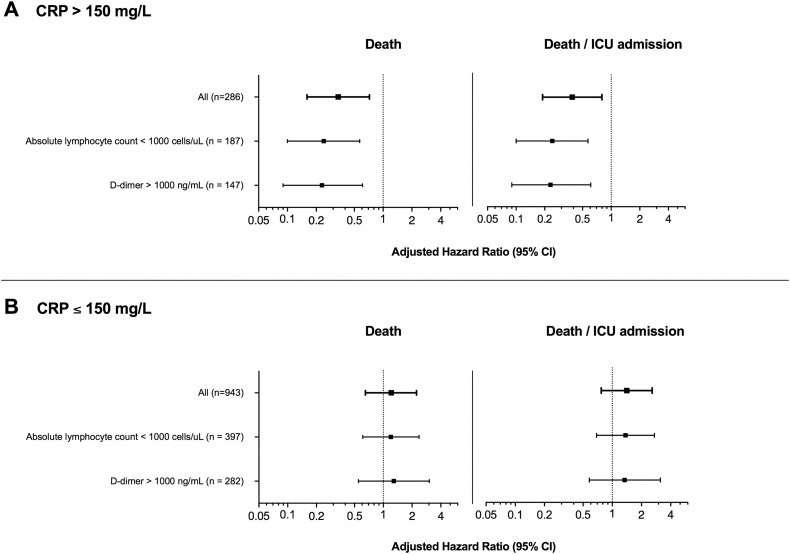

Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3 show the aHRs for exploratory sensitivity analyses restricted to patients with added risk factors for poor prognosis (i.e. baseline lymphocyte count <1000 cell/μL and baseline d-dimer >1000 ng/mL), segregated by CRP levels. The results are consistent with the principal analysis. Individuals with baseline CRP levels >150 mg/L who received tocilizumab maintained a lower risk of death and ICU/death, but no significant effects of tocilizumab were found among those with low CRP levels.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for sensitivity analyses according to baseline laboratory absolute lymphocyte counts and d-dimer. Weighted hazard ratios derived from marginal structural models adjusted for sex, age, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, lung disease), need for oxygen therapy at baseline, oxygen blood saturation and time-varying parameters of severity (blood pressure, heart rate, total lymphocyte and neutrophil count, LDH, ALT, urea, d-dimer and CRP). ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

We also explored the effects of concomitant therapies against SARS-CoV-2 in sensitivity analyses restricted to patients who received corticosteroids (n = 582), hydroxychloroquine (n = 1134), azithromycin (n = 812) or lopinavir/ritonavir (n = 753) (Supplementary Table S3). The estimates of the effect of tocilizumab among subjects with baseline CRP >150 mg/L who received these concomitant treatments were very similar to those observed in the principal analyses for both the primary and secondary outcomes (all p < 0.05 except azithromycin and lopinavir/ritonavir, with p 0.105 in the primary and p 0.079 in the secondary outcome respectively).

Discussion

While the overall risk of death or ICU admission did not differ between patients who received tocilizumab and those who did not and who had CRP levels ≤150 mg/L, we found a 66% reduction in the risk of mortality in patients with baseline CRP levels >150 mg/L who received tocilizumab. Exploratory sensitivity analyses to account for the use of concomitant therapies against SARS-CoV-2 or the presence of other analytical parameters predictive of poor prognosis yielded consistent treatment effect estimates.

Early reports suggest that systemic inhibition of IL-6 signaling is beneficial in the treatment of severe COVID-19 [7,20,21]. The original observational study of 21 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, reported that tocilizumab resulted in resolution of fever in all patients 1 day after treatment as well as improvement of peripheral oxygen saturation and lymphopenia. Moreover, 19 of 20 patients who received tocilizumab presented a radiologic improvement in the computed tomographic scan after 5 days [10]. In a single-arm study of 63 patients with a proinflammatory and prothrombotic state due to severe COVID-19, treatment with tocilizumab was associated with a decrease in CRP, d-dimer and ferritin levels [9]. Thus, tocilizumab and other repurposed medications have been widely used off-label to treat COVID-19 in an attempt to mitigate the dramatic clinical consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection, despite the lack of robust information on the effects of tocilizumab on clinical outcomes. Recent press releases of clinical trials with anti–IL-6 agents (sarilumab and tocilizumab) have reported that these drugs have not met their endpoints, although studies are still being conducted in different treatment settings [22,23].

In our cohort, controls were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of hypertension, which are the risk factors that have been more robustly associated with severe COVID-19 and death [6,18,24,25]. However, subjects who received tocilizumab tended to have a greater prevalence of other potential risk factors for disease severity such as previous lung disease, as well as differences in baseline vital signs and laboratory parameters indicative of greater immune activation. All of these factors were included as covariates, and the estimates were consistent across the two endpoints analysed.

The selection of the modeling strategy was a critical decision. Longitudinal studies in which exposures, confounders and outcomes are measured repeatedly over time can facilitate causal inferences about the effects of exposure on outcome [17]. However, there are key analytical issues in this setting, including the risk of immortal time bias (i.e. the requirement for patients to survive long enough to receive the intervention of interest, which can lead to a potentially incorrect estimation of a positive treatment effect) and indication bias from time-varying confounding (e.g. receipt of tocilizumab after CRP elevations) [17,26]. Standard regression models for the analysis of cohort studies with time-updated measurements may result in biased estimates of treatment effects if time-dependent confounders affected by prior treatment are present [17,28]. Marginal structural models, similar to the time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models, are a powerful method of controlling for confounding in longitudinal study designs that collect time-varying information on exposure, outcome and other covariates, such as the present one [16,17]. These models aim to appropriately control for the effects of time-varying confounders that are affected by prior treatment (exposure) and attempt to enhance group comparability and estimate causal effects in a similar way [27].

Our study has a number of limitations. As with any observational study, there is still a risk of unmeasured confounding, as well as indication and immortal time biases, despite having focused the methodology on avoiding them. Tocilizumab targets the IL-6 receptor; thus, using baseline IL-6 levels instead of CRP in the interaction term with receipt of tocilizumab could have helped to better discriminate the population benefiting most from tocilizumab treatment. Although IL-6 measurements are rarely available in clinical settings, CRP is widely accessible and is an inflammatory biomarker upstream of the IL-6 pathway [5]. Hence, we doubt that the use of CRP instead of IL-6 limited the scope of the results. Ongoing trials of tocilizumab in COVID-19 have also considered CRP instead of IL-6 to identify patients with heightened inflammation and therefore potential greater benefit with this treatment (NCT04346355 and NCT04356937). Even though the size effects observed in the sensitivity analyses were consistent with those obtained in the principal analyses, they should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis generating. In addition, we could not analyse the rate of new infectious, which was higher with tocilizumab in a previous observational study [8].

In summary, we analysed a large number of consecutive patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and found that tocilizumab was associated with a lower risk of mortality or ICU/death among patients with CRP >150 mg/L but not among those with lower CRP levels. Although the results of ongoing clinical trials of tocilizumab in patients with COVID-19 are needed to establish its safety and efficacy, our findings might be helpful in the design of future clinical trials.

Transparency declaration

Outside the submitted work, SSV reports personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen-Cilag, Gilead Sciences and MSD; nonfinancial support from ViiV Healthcare and Gilead Sciences; and research grants from MSD and Gilead Sciences. JMS reports nonfinancial support from ViiV Healthcare, Jannsen Cilag and Gilead Sciences. JAP reports grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from ViiV Healthcare and grants from MSD outside the submitted work. SM reports grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from ViiV Healthcare; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Janssen; and grants, personal fees and nonfinancial support from MSD and Gilead outside the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all study participants, who made this research possible. We thank the HM Hospitales group for releasing the data set used to perform this research to the scientific community.

Editor: L. Leibovici

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.021.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalil A.C. Treating COVID-19—off-label drug use, compassionate use, and randomized clinical trials during pandemics. JAMA. 2020;323:1897. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Navarro G., Taroumian S., Barroso N., Duan L., Furst D. Tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of efficacy and selected clinical conundrums. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokota S., Miyamae T., Imagawa T., Iwata N., Katakura S., Mori M. Therapeutic efficacy of humanized recombinant anti–interleukin-6 receptor antibody in children with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:818–825. doi: 10.1002/art.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridker P.M. From C-reactive protein to interleukin-6 to interleukin-1: moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection. Circ Res. 2016;118:145–156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang C., Wu Z., Li J.W., Zhao H., Wang G.Q. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guaraldi G., Meschiari M., Cozzi-Lepri A., Milic J., Tonelli R., Menozzi M. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30173-9. (ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sciascia S., Aprà F., Baffa A., Baldovino S., Boaro D., Boero R. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X., Han M., Li T., Sun W., Wang D., Fu B. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radbel J., Narayanan N., Bhatt P.J. Chest; 2020. Use of tocilizumab for COVID-19–induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo P., Liu Y., Qiu L., Liu X., Liu D., Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: a single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toniati P., Piva S., Cattalini M., Garrafa E., Regola F., Castelli F. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: a single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102568. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HM Hospitales (Spain) COVID data save lives. https://www.hmhospitales.com/coronavirus/covid-data-save-lives/english-version Available at:

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO) Family of international classifications. https://www.who.int/classifications/en/ Available at:

- 16.Hernán M.Á., Brumback B., Robins J.M. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000;11:561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fewell Z., Hernán M.A., Wolfe F., Tilling K., Choi H., Sterne J.A.C. Controlling for time-dependent confounding using marginal structural models. Stata J Promot Commun Stat Stata. 2004;4:402–420. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang W., Liang H., Ou L., Chen B., Chen A., Li C. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Gun B. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus–induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanofi Sanofi and Regeneron provide update on Kevzara® (sarilumab) phase 3 US trial in COVID-19 patients. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-07-02-22-30-00 Available at:

- 23.Roche Roche provides an update on the phase III COVACTA trial of Actemra/RoActemra in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. https://www.roche.com/investors/updates/inv-update-2020-07-29.htm Available at:

- 24.Jordan R.E., Adab P., Cheng K.K. COVID-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuin M., Rigatelli G., Zuliani G., Rigatelli A., Mazza A., Roncon L. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e84–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lévesque L.E., Hanley J.A., Kezouh A., Suissa S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ. 2010;340:907–911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williamson T., Ravani P. Marginal structural models in clinical research: when and how to use them? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:ii84–ii90. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.