Abstract

Objective:

To describe the relationship between caregiver-specific support and conflict, and psychosocial outcomes among individuals experiencing their first dysvascular lower extremity amputation (LEA).

Design:

Cross-sectional cohort study using self-report surveys.

Setting:

Department of Veterans Affairs, academic medical center, and level I trauma center.

Participants:

Individuals undergoing their first major LEA because of complications of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) or diabetes who have a caregiver and completed measures of caregiver support and conflict (N = 137; 94.9% men).

Interventions:

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures:

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to assess depression and the Satisfaction With Life Scale to assess life satisfaction.

Results:

In multiple regression analyses, controlling for global levels of perceived support, self-rated health, age, and mobility, caregiver-specific support was found to be associated with higher levels of life satisfaction and caregiver-specific conflict was found to be associated with lower levels of life satisfaction and higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Conclusions:

The specific relationship between individuals with limb loss and their caregivers may be an important determinant of well-being. Conflict with caregivers, which has received little attention thus far in the limb loss literature, appears to play a particularly important role. Individuals with limb loss may benefit from interventions with their caregivers that both enhance support and reduce conflict.

Keywords: Amputation, Caregivers, Depression, Rehabilitation, Social support

Approximately 2 million individuals in the United States currently live with limb loss.1 Individuals face significant physical and psychological challenges in the initial phase of recovery from amputation, including loss of mobility,2 phantom limb pain,3 social isolation,2 depression and anxiety,4,5 and elevated rates of suicidal ideation.6 Evidence from the health literature suggests that interpersonal factors (eg, social support, conflict) may play a significant role in outcomes of individuals with limb loss. Across a variety of illness groups, individuals who perceive greater levels of available support report higher quality of life,7 report fewer physical health symptoms,8 and are more likely to adhere to their medications and self-management regimens.9,10 Two prominent theories used to explain the relationship between social support and health outcomes buffering model vs direct effect model suggest that social support either mitigates the negative effect of illness or directly impacts physical and mental health.11 Relationship conflict, although less studied in the health literature, has also been found to be associated with disease outcomes; those who perceive higher levels of interpersonal conflict in their primary relationship engage in poorer disease management.9,12,13

Among individuals with limb loss, perceived social support has also been shown to be associated with important health and psychological outcomes in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Individuals with limb loss who perceive greater levels of available support have been shown to have higher quality of life14 and life satisfaction,15 greater mobility,15,16 lower levels of depressive symptoms,15,17 less pain intensity,17,18 decreased pain interference,15 and better overall adjustment.19,20 Notably, this prior research focused exclusively on support that patients perceive in their social network as a whole, rather than on support from a specific person or caregiver. Because those with limb loss tend to have increased medical needs and are more likely to have a formal or informal caregiver, the nature of the relationship between the individual and the caregiver may be especially relevant.

In the months after limb loss, when individuals need increased assistance with activities of daily living, perceptions of caregiver support and conflict likely play a role in physical and psychological functioning.21 Network support, in comparison, may be less relevant to overall well-being among individuals with recent amputations, given their need to establish basic functioning, which is likely best served through 1-on-1 care. Additionally, caregiver-specific support and conflict is potentially more modifiable than a patient’s overall level of perceived support from his or her broader social network; therefore, examination of the role of caregiver-specific support and conflict can potentially inform the development of dyadic interventions that would be more feasible to implement than interventions aimed at an entire social network.

This study examined the relationship between caregiver-specific support and conflict, and depression and life satisfaction among individuals experiencing their first lower limb amputation. To help distinguish the roles of global versus caregiver-specific support, global perceived support was included as a covariate in all analyses. We expected that caregiver-specific support would be associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms and higher levels of life satisfaction, and that caregiver-specific conflict would be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and lower levels of life satisfaction.

Methods

Study design

This study is a secondary analysis of 2 larger multisite prospective cohort studies conducted with individuals undergoing their first major lower extremity amputation because of complications of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) or diabetes. The first study was conducted between 2005 and 2009 at 4 sites: 2 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers (located in Seattle and Denver), a Seattle-area university hospital, and a Seattle-based level I trauma center. The second study was conducted between 2010 and 2014 at 4 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers (located in Seattle, Portland, Houston, and Dallas). To increase study power and to expand the generalizability of the model, both datasets were combined, ensuring a broad geographic and temporal range. Study operations and data elements collected were comparable for each study. The decision to perform transmetatarsal, transtibial, or transfemoral amputation was made at each site per usual care; rehabilitation protocols were also completed per usual care. Participants were assessed verbally in-person or via telephone within 6 weeks after the definitive amputation procedure for baseline data and 12 months postsurgically. Additional data were gathered via systematic review of medical records, and aspects of interview data were verified against the medical record. All instruments were administered by a trained study coordinator designated for each site. These studies were conducted in accordance with procedures approved by human subjects review boards at each participating institution. All participants provided informed consent.

Participants

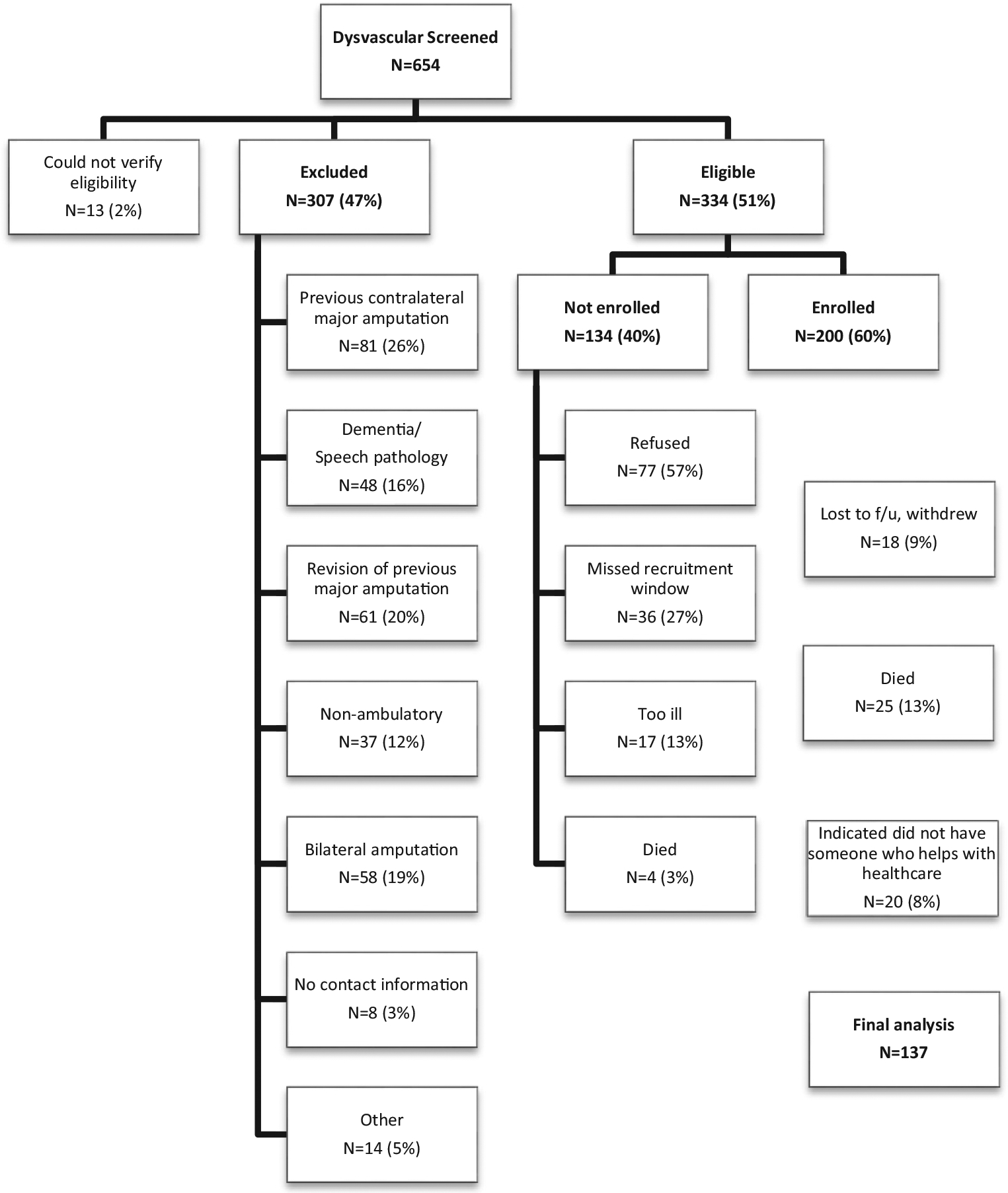

Potential study candidates were referred by wound care clinics, patient rounds, and physicians and nurses working with the patients, and consented by study coordinators. Participants were eligible if (1) they were age ≥18 years and (2) they were awaiting (or underwent in the last 6wk) a first major lower extremity amputation (transmetatarsal, transtibial or transfemoral) related to complications of diabetes mellitus or PAD. Participants were excluded if (1) they had inadequate cognitive or language function to consent or participate defined by >4 errors on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire or (2) they were nonambulatory before the amputation for reasons unrelated to PAD or diabetes. A STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology diagram of study enrollment is included in figure 1.

Fig 1.

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology diagram depicting total numbers excluded, not enrolled, enrolled, and at final 12-month follow-up for study cohort.

Measures

Demographic/baseline health

Baseline measures included demographics (age, sex, race, marital status, and educational attainment), information about the amputation, and health factors (presence of PAD, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension diagnoses).

Quality of Relationship Inventory

The perceived quality of the relationship between study participants and their caregivers was assessed at 12 months postamputation using the Quality of Relationship Inventory (QRI)22 Short Form. First, participants were asked to identify the person who helped them the most with their health care, and whether this person lived with them. The 6 QRI items then referenced this caregiver relationship. Relationship support was assessed with 3 items (“Could you turn to this person for advice about problems?”; “Could you count on this person for help with a problem?”; and “Can you count on this person to listen to you when you are very angry at someone else?”). Relationship conflict was assessed with 3 additional items (“Do you need to work hard to avoid conflict with this person?”; “How upset does this person make you feel?”; and “How angry does this person make you feel?”). For all 6 items, response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). QRI subscale scores were created by calculating the mean scores for the support and conflict items. Higher scores indicated greater support and greater conflict with the individual who provides the most help with the patient’s health care. The QRI Short Form has been used in other studies with good reliability.10

Global life satisfaction

Twelve-month global life satisfaction was assessed using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS).23 Scores on the SWLS are generally stable over time, yet remain sensitive enough to demonstrate changes in response to clinical interventions.24 The SWLS consists of 5 items scored on a Likert scale where 1 is strongly disagree and 7 is strongly agree. Scores are summed, with possible totals ranging from 5 to 35; higher scores indicate greater global life satisfaction.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms at 12 months post amputation were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, a well-validated self-report screening instrument.25–28 The module instructs participants to rate the degree to which they experienced each of 9 symptoms of depression over the last 2 weeks, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Possible sum scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores representing greater depressive symptoms.

Global social support

Global perceived social support at 12 months postamputation was assessed using the brief version of the Modified Social Support Survey (MSSS),29 which assesses the extent to which individuals feel they can count on others for various needs (eg, to take you to the doctor if you need it, to love and make you feel wanted). Participants are asked to think of their entire social network, rather than a specific relationship. The MSSS was initially developed as part of the Medical Outcomes Study and was subsequently shortened as part of the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory.30 In this brief format, possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater support.

Mobility

Mobility was assessed at 12 months postamputation using the Locomotor Capability Index-5.31 The Locomotor Capability Index-5 consists of 14 items graded on a 5-level ordinal scale ranging from an inability to perform the activity (0) to being able to perform it without ambulation aids (4). It demonstrates good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, ceiling effect, and effect size.32 Possible scores range from 0 to 56, with higher scores representing higher functional mobility.

Self-rated health

Self-rated health (SRH) at 12 months postamputation was assessed via a single item modeled after the general health question from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.33 Response options were very poor, poor, fair, good, and very good. Possible scores ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better self-assessed overall health. This single-item index has been used extensively and has the advantage of ease and simplicity of administration.34,35

Data analysis

To compare the individuals who completed the QRI items (N = 137) with those who did not and were therefore excluded here (n = 20), 1-way analyses of variance and χ2 analyses were conducted for baseline health characteristics and 12-month variables of interest.

To determine if there were confounding factors contributing to depressive symptoms or overall satisfaction with life, separate univariate analyses were conducted with depressive symptoms and global satisfaction with life as outcomes, and mobility, SRH, age, and race as independent variables. All these variables, with the exception of race (to our knowledge), have previously been found to be associated with psychological adjustment among individuals with limb loss.36–38 If an independent variable was significantly associated with an outcome (either global life satisfaction or depressive symptoms) at P<.10, it was included in the multivariable analysis. Given that the QRI subscales are thought to provide unique information above and beyond a measure of global social support, the MSSS was included in all multivariable models, regardless of whether it was significantly associated with the outcome variable.

After completing univariate analyses, 2 forced-entry multivariable regression analyses were conducted with global satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms as outcomes, and QRI support and conflict subscales as the independent variables, controlling for global perceived social support and any other factors found to be significantly associated with the outcome variables at the univariate level. Statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 19.0.a

Results

Sample characteristics

This sample was comprised predominantly of white (77%), male (95%) Veterans (90%) (table 1). For the 137 participants who indicated that they have someone who helps them with their medical care, the relationship and whether that person lives with the patient are described in table 2; the sample was too small to run analyses evaluating the role of relationship type. Overall, participants indicated high support and low conflict in their relationship with the individual who helps them with their health care (table 3).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and health characteristics of study participants (N = 137)

| Sociodemographic and Baseline Health Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 130 (94.9) |

| Veteran | 179 (89.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 105 (76.6) |

| Other | 32 (23.4) |

| Years of education | 13.65±1.96 (10–20) |

| Age (y) | 62.22±7.74 (43–89) |

| Married/partnered | 81 (59.1) |

| Amputation level | |

| Transmetatarsal | 41 (29.9) |

| Transtibial | 75 (54.7) |

| Transfemoral | 21 (15.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 111 (81.0) |

NOTE. N = 137. Values are mean ± SD (range) or n (%).

Table 2.

Identified caregiver (N = 137)

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Who helps most with health care? | |

| Spouse/partner | 66 (48.2) |

| Son or daughter | 15 (10.9) |

| Another family member | 21 (15.3) |

| Paid caregiver | 15 (10.9) |

| Friend | 16 (11.7) |

| Other | 4 (2.9) |

| Does this person live with participant? | |

| Yes | 96 (70.1) |

| No | 41 (29.9) |

Table 3.

Twelve-month health characteristics of study population (N = 136–137)

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Possible Range | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility (LCI-5) | 35.96±17.27 | 0–56 | .96 |

| SRH (single item) | 3.39±0.91 | 1–5 | n/a |

| Satisfaction with life (SWLS) | 21.21±8.85 | 5–35 | .88 |

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | 5.81±6.21 | 0–27 | .88 |

| Perceived global social support (MSSS) | 78.87±22.83 | 0–100 | .84 |

| QRI support subscale | 3.44±0.71 | 1–4 | .82 |

| QRI conflict subscale | 1.44±0.61 | 1–4 | .82 |

Abbreviations: LCI-5, Locomotor Capability Index-5; n/a, not applicable; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

The 137 individuals who completed the QRI items reported greater perceived social support (mean, 78.87±22.83) than those (n=20) who did not complete these items (either because they declined to answer the questions or because they indicated that no one helped them with their medical care) (mean, 33.67±24.96; F1,150=52.04; P<.001). Similarly, those who completed the QRI subscales reported higher overall satisfaction with life (mean, 21.21±8.85) relative to those who did not complete the measures (mean, 15.53±8.24; F1,150=5.63; P=.02). Those who did not complete QRI measures were less likely to be married than those who did complete the items (, P<.01). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups on other variables of interest.

Univariate analyses

In univariate linear regression analyses, higher global satisfaction with life at 12 months postamputation was associated with older age (β=.23; P<.01; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] .08–.44), greater concurrent mobility (β=.28; P<.001; 95% CI, .07–.23), and better concurrent SRH (β=0.40; P<.001; 95% CI, 2.53–5.51). Therefore, age, mobility, and SRH were included in the final model for global life satisfaction. Race was not significantly associated with global life satisfaction; as such, it was not included in subsequent analyses. Greater depressive symptoms at 12 months postamputation were associated, in univariate analyses, with younger age (β= −.34; P<.001; 95% CI, −.39 to −.15) and worse concurrent SRH (β= −0.39; P<.001; 95% CI, −3.84 to −1.70). Therefore, these 2 variables were included in the final model for depressive symptoms. Neither concurrent mobility nor race was significantly associated with depressive symptoms at the univariate level; therefore, they were not included in subsequent analyses.

Support and conflict analyses

Both QRI support and QRI conflict scores were significantly associated with global satisfaction with life in a forced-entry multivariable linear regression, after controlling for global perceived social support, age, mobility, and SRH (table 4). QRI conflict scores were significantly associated with 12-month depressive symptoms, after controlling for global perceived social support, age, and SRH. QRI support scores were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms in the multivariable model (see table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable models for global satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms at 12 months postamputation (N = 136–137)

| Variable | Life Satisfaction (SWLS) | Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Constant | −29.85 to −2.51 | 9.32 to 27.41 | ||

| QRI support subscale | .19* | .17 to 4.51 | .13 | −0.39 to 2.62 |

| QRI conflict subscale | −15* | −4.38 to −0.09 | .38† | 2.38 to 5.32 |

| Global support (MSSS) | .01 | −0.07 to 0.07 | −.16 | −0.09 to 0.01 |

| Age | .26‡ | 0.12 to 0.48 | −.24‡ | −0.31 to −0.07 |

| SRH | .25‡ | 0.94 to 3.91 | −.29† | −2.97 to −0.98 |

| Mobility (LCI-5) | .30† | 0.08 to 0.231 | NA | NA |

NOTE. N = 136–137. Twelve-month mobility was not significantly associated with concurrent depressive symptoms at the univariate level; therefore, mobility was not included in the multivariable model for depressive symptoms.

Abbreviations: LCI-5, Locomotor Capability Index-5; NA, Not Applicable; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

P<.05.

P<.001.

P<.01.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between caregiver support and conflict and psychosocial outcomes among individuals with limb loss 12 months after their amputation procedures. Results indicated that conflict with caregivers is associated with depressive symptoms, and both caregiver support and conflict are associated with life satisfaction, after controlling for other variables significantly associated with depression and life satisfaction. Given that, on average, participants generally felt well supported by their network (average global perceived support was high), these findings underscore the importance of examining caregiver-specific support and conflict when considering the effect of an individual’s support system on well-being.

This study furthers our understanding of the relationship between individuals’ support networks and well-being among those recovering from limb loss. One study found an association between individuals’ sense of comfort in discussing their amputation with the most important person in their lives and depressive symptoms,39 but otherwise the prior literature has focused on general support systems and not on any specific relation in individuals’ networks. Because global perceived support was controlled for in all analyses in this study, our findings demonstrate the unique importance of individuals’ relationships with caregivers.

These results highlight the importance of conflict in relationships. Social support has been frequently examined, but negative interaction patterns have been less thoroughly explored among individuals with limb loss. Our results were in line with the literature from other medical populations which have generally found that relationship conflict is associated with poorer psychological adjustment.40,41 Given the relationship between conflict and both life satisfaction and depression, our findings demonstrate that assessing support is insufficient for understanding how patients’ relationships may impact important outcomes. This is consistent with prior literature which has shown that perceived criticism and demandingness from family and friends are associated with depression among individuals with limb loss.39 Notably, for life satisfaction, the effect sizes of caregiver support and conflict were roughly equivalent, suggesting that conflict may be equally as important as support. It is possible that given the close contact required of caregiving for individuals with limb loss, the presence of conflict may have a particularly toxic effect. Asking individuals about conflict with their caregiver may help identify patients who may be particularly vulnerable. Using items from the QRI can provide guidance on the types of questions that would be useful.

Given the limited literature on the relationship between caregiver conflict and well-being among patients with limb loss, these findings emphasize the importance of further study of this construct using longitudinal approaches because it may prove to be an important intervention target. Interventions aimed at reducing conflict among couples, for example, have shown positive benefits on depressive symptoms and other outcomes.42,43 Adapting these interventions to the context of patients with limb loss may prove beneficial. Given that almost half of caregivers in our sample were not family members, flexible interventions are needed that can be adapted to different types of relationships.

Study limitations

Limitations of this study include the use of a self-report measure to assess depression. Because of its cross-sectional design, we cannot establish the directionality of associations when measuring risk factors and outcomes concurrently. Therefore, we cannot be certain if conflict with caregivers contributes to depression and lower levels of life satisfaction or vice versa. Additionally, because of sample size considerations, we were unable to explore whether there was a moderating effect of relationship type (eg, spouse vs paid caregiver). Also, given that the sample was 95% men, these findings are not necessarily generalizable to women with limb loss. Prior literature has found that women are more susceptible to depressogenic effects of low social support than men; therefore, contrary to these present findings, low caregiver support may play a role in depression for women with limb loss.44 Finally, individuals who noted that they did not have a caregiver were not included in this sample; therefore, our results do not generalize to this subset of individuals.

Despite its limitations, this study has numerous strengths, including statistical control for general perceived support and simultaneous consideration of both support and conflict. These findings suggest that longitudinal research is needed to further explore the role of caregiver conflict because it may prove to be a fruitful (and, as of yet, largely unaddressed) target of interventions for improving the overall well-being of individuals with limb loss. A more nuanced investigation of how conflict may differ between different caregiver types (eg, spouse vs offspring vs paid caregiver) may also provide guidance on how to effectively intervene.

Conclusions

The specific relationship between individuals with limb loss and their caregivers may be an important determinant of well-being. Conflict with caregivers, which has received little attention thus far in the limb loss literature, appears to play a particularly important role. Individuals with limb loss may benefit from interventions with their caregivers that both enhance support and reduce conflict.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development (merit review no. A41241 and career development award no. B4927W).

List of abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- MSSS

Modified Social Support Survey

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- QRI

Quality of Relationship Inventory

- SRH

self-rated health

- SWLS

Satisfaction With Life Scale

Footnotes

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 19.0; IBM.

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pell JP, Donnan PT, Fowkes FG, Ruckley CV. Quality of life following lower limb amputation for peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Surg 1993;7:448–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen TS, Krebs B, Nielsen J, Rasmussen P. Immediate and long-term phantom limb pain in amputees: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to pre-amputation limb pain. Pain 1985;21:267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:837–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mckechnie P, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury 2014;45:1859–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner AP, Meites TM, Williams RM, et al. Suicidal ideation among individuals with dysvascular lower extremity amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:1404–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2007;16:474–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton E, Vosvick M, Chesney M, et al. Social support and maladaptive coping as predictors of the change in physical health symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDs. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19:587–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2004;23:207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel SD, Turner AP, Haselkorn JK. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: does caregiver social support matter? Rehabil Psychol 2008;53:73. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penninx BW, Van Tilburg T, Deeg DJ, Kriegsman DM, Boeke AJ, Van Eijk JT. Direct and buffer effects of social support and personal coping resources in individuals with arthritis. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baron KG, Smith TW, Czajkowski LA, Gunn HE, Jones CR. Relationship quality and cpap adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Behav Sleep Med 2009;7:22–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesla CA, Fisher L, Mullan JT, et al. Family and disease management in african-american patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2850–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int 2008;32:231–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RM, Ehde DM, Smith DG, Czerniecki JM, Hoffman AJ, Robinson LR. A two-year longitudinal study of social support following amputation. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:862–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czerniecki JM, Turner AP, Williams RM, Hakimi KN, Norvell DC. The effect of rehabilitation in a comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation unit on mobility outcome after dysvascular lower extremity amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:1384–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Ehde DM, Hoffman AJ, Patterson DR, Robinson LR. Psychosocial predictors of long-term adjustment to lower-limb amputation and phantom limb pain. Disabil Rehabil 2004; 26:882–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallagher P, Allen D, Maclachlan M. Phantom limb pain and residual limb pain following lower limb amputation: a descriptive analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2001;23:522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyc VL. Psychosocial adaptation of children and adolescents with limb deficiencies: a review. Clin Psychol Rev 1992;12:275–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unwin J, Kacperek L, Clarke C. A prospective study of positive adjustment to lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:1044–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson DR, Roubinov D, Turner A, Williams R, Norvell D, Czerniecki J. Social support moderates the relationship between pre-surgical activities of daily living and depression after lower limb loss. Rehabil Psychol; In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: are two constructs better than one? J Pers Soc Psychol 1991;61:1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess 1993;5:164. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin A, Rief W, Klaiberg A, Braehler E. Validity of the brief patient health questionnaire mood scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disord 2004;81:61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritvo PG, Fischer JS, Miller DM, Andrews H, Paty DW, LaRocca NG. Multiple sclerosis quality of life inventory: a user’s manual. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grise MC, Gauthier-Gagnon C, Martineau GG. Prosthetic profile of people with lower extremity amputation: conception and design of a follow-up questionnaire. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993;74:862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franchignoni F, Orlandini D, Ferriero G, Moscato TA. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the locomotor capabilities index in adults with lower-limb amputation undergoing prosthetic training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verbrugge LM, Merrill SS, Liu X. Measuring disability with parsimony. Disabil Rehabil 1999;21:295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloan JA, Aaronson N, Cappelleri JC, Fairclough DL, Varricchio C; Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Assessing the clinical significance of single items relative to summated scores. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:479–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frank RG, Kashani JH, Kashani SR, Wonderlich S, Umlauf RL, Ashkanazi GS. Psychological response to amputation as a function of age and time since amputation. Br J Psychiatry 1984;144: 493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson GM. The central role of restricted normal activities in adjustment to illness and disability: a model of depressed affect. Rehabil Psychol 1998;43:327. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rybarczyk B, Nyenhuis DL, Nicholas JJ, Cash SM, Kaiser J. Body image, perceived social stigma, and the prediction of psychosocial adjustment to leg amputation. Rehabil Psychol 1995;40:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kratz AL, Williams RM, Turner AP, Raichle KA, Smith DG, Ehde D. To lump or to split? Comparing individuals with traumatic and non-traumatic limb loss in the first year after amputation. Rehabil Psychol 2010;55:126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giese-Davis J, Hermanson K, Koopman C, Weibel D, Spiegel D. Quality of couples’ relationship and adjustment to metastatic breast cancer. J Fam Psychol 2000;14:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manne SL, Zautra AJ. Couples coping with chronic illness: women with rheumatoid arthritis and their healthy husbands. J Behav Med 1990;13:327–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:317–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: a longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]