Abstract

Background

Female genital mutilation (FGM) includes all procedures that intentionally harm or alter female genitalia for non-medical reasons. In 2015, reporting duties were introduced, applicable to GPs working in England including a mandatory reporting duty and FGM Enhanced Dataset. Our patient and public involvement work identified the exploration of potential impacts of these duties as a research priority.

Aim

To explore the perspectives of GPs working in England on potential challenges and resource needs when supporting women and families affected by FGM.

Design and setting

Qualitative study with GPs working in English primary care.

Method

Semi-structured interviews focused around a fictional scenario of managing FGM in primary care. The authors spoke to 17 GPs from five English cities, including those who saw women who have experienced FGM often, rarely, or never. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis. Lipsky’s theory of street-level bureaucracy was drawn on to support analysis.

Results

Managing women with FGM was experienced as complex. Challenges included knowing how and when to speak about FGM, balancing care of women and their family’s potential care and safeguarding needs, and managing the mandated reporting and recording requirements. GPs described strategies to manage these tensions that helped them balance maintaining patient–doctor relationships with reporting requirements. This was facilitated by access to FGM holistic services.

Conclusion

FGM reporting requirements complicate consultations. The potential consequences on trust between women affected by FGM and their GP are clear. The tensions that GPs experience in supporting women affected by FGM can be understood through the theoretical lens of street-level bureaucracy. This is likely to be relevant to other areas of proposed mandated reporting.

Keywords: genital mutilation, GP; mandatory reporting; qualitative research; street-level bureaucracy

INTRODUCTION

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is defined by the World Health Organization as ‘ all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons’.1 FGM has no known health benefits, and many documented harms.1 Potential harms include immediate risks; such as haemorrhage, infection, and death; enduring risks, including obstetric complications, menstrual and urinary problems; and psychological impacts including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.2 An estimated 200 million women and girls in 30 countries are living with the consequences of FGM.3 Global migration from areas where FGM is traditionally practised means that FGM is a worldwide health concern.

Using household survey data on FGM prevalence in countries where FGM is traditionally practised, and the UK 2011 census and birth registration data, MacFarlane et al estimated that approximately 137 000 women and girls born in countries where FGM is traditionally practised were permanently resident in England and Wales in 2011. Though there was significantly higher prevalence in urban areas, it was estimated that there would be no local authority areas without any women affected by FGM.4 Therefore, it seems likely that many English GPs will have clinical encounters with women and families potentially affected by FGM. Understanding how to support affected families and meet their care needs is vital, and the recent increase in service provision recognising the needs of women and communities affected by FGM is timely and welcome.5

FGM is an ancient cultural practice that has been the focus of recent education, safeguarding, and policy.

In July 2014, the UK government hosted the first Girl Summit, in partnership with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), at which they pledged to mobilise domestic and international efforts to eliminate FGM within a generation.6 The prime minister announced a raft of measures including legislative changes, a GBP 1.4 million FGM Prevention Programme with NHS England, and training for professionals.6

Following this, policy introduced in 2015 included a mandatory reporting duty; requiring all registered professionals in England and Wales to report cases of FGM in those aged <18 years directly to the police when FGM was identified on examination, or through first-hand disclosure. The consequences for not doing so include professional sanctions.7 An FGM Enhanced Dataset (applicable in England) was also introduced, requiring submission of quarterly data returns, including personally identifiable data (such as name, date of birth, and NHS number) to NHS Digital from all NHS acute trusts and GP practices. The stated aim of the FGM Enhanced Dataset is to support the DHSC FGM Prevention Programme by providing prevalence data of FGM in the NHS in England. Consent for data sharing is not required, however fair processing requires clinicians to explain the dataset to their patients.8,9

How this fits in

| The authors are unaware of any previous work considering GPs’ perspectives on supporting women with female genital mutilation (FGM) in primary care, including the impacts of recent English policy which includes a mandatory reporting policy and FGM Enhanced Dataset. GPs described tensions between their caring role and the policy requirements placed on them. The provision of specialist support, and holistic education could support GPs when caring for those from communities affected by FGM. |

Concerns about the potential impacts of these two policies have been raised by both professionals and community members.10–16 In the most recent data report for the FGM Enhanced Dataset, only 59 GP practices submitted attendance data in the year 2019–2020.17 There were approximately 6813 GP practices in England in February 2020.18

A patient and public involvement project to understand research priorities highlighted questions about how this legislation might affect trust in healthcare interactions.19 There is very little research about the primary care role in supporting women with FGM.20 The authors are aware of no published research considering English GPs’ perspectives in the context of recent policy.

Street-level bureaucracy is a sociological theory advanced by Michael Lipsky that seeks to explain how public servants think and act when they are delivering public policy in the course of their work on the service front line. Lipsky found that professionals typically face constraints (such as excessive workloads, or limited time and resources), which limit their ability to respond to (all) of their individual clients’ needs. Professionals therefore tend to develop routines of practice, which inevitably influence outcomes. Lipsky described professionals working in this way as ‘street-level bureaucrats’. Exercising professional discretion is central to the work of street-level bureaucrats, who face, what Lipsky describes, an ‘essential paradox’:

‘On the one hand, the work is often highly scripted to achieve policy objectives that have their origins in the political process. On the other hand, the work requires improvisation and responsiveness to the individual case.’21

It has been suggested that Lipsky’s observations apply to the work of GPs who are faced with enacting policy while trying to maintain a trusting therapeutic relationship with their patients.22–24 In this study, Lipsky’s theory is drawn on to explore GPs’ perspectives on supporting patients who may be affected by FGM.

METHOD

Study design

This was a qualitative study using semi-structured telephone interviews with GPs based around a fictional scenario (Box 1) of a woman (‘Samara’) presenting to primary care and seeking support for her FGM. The scenario was piloted with two GPs and designed to resonate with scenarios likely to be encountered in FGM-related education.

Box 1.

Fictional scenario of a woman presenting to primary care seeking support for female genital mutilation

| Samara is a 22-year-old woman. Born in Somalia, she came to the UK 8 years ago with her parents, sister, and brother. She finished her education in England and speaks good English. She comes to see you because she is going to get married shortly and would like to be referred to be opened up before her marriage having been ‘closed’ as a child in Somalia. Six months later, she comes back to tell you she is now pregnant with her first child and would like to be referred for antenatal care. |

Sampling and recruitment

GP practices in eight English cities in the Southeast, Southwest, Midlands, and Northwest regions were contacted once by email with information about the study. Using the published list of FGM specialist clinics from NHS England at the time of study recruitment, both cities that had a local specialist clinic and those that did not were chosen. Aiming to speak to GPs with different levels of exposure to FGM, and by using published local maps of demographics and ethnicity, those areas likely to have practice populations with differing prevalence of FGM were selected. In addition, where possible, the Named GP for safeguarding in these cities was approached by email to ask whether they would consider sharing the study information through their local networks. Recruitment was enhanced through snowballing.

A total of 17 GPs (n = 16 female, n = 1 male) from five English cities, with a range of experience, and with varying access to a local specialist clinic, participated in the study.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted by the first author (a GP and a National Institute for Health Research in-practice fellow) between March and November 2018.

The fictional scenario was used to help create a neutral space for GPs to consider possible responses to issues they might face when seeing women affected by FGM, and strategies or resources that might help.25,26 GPs were then invited to reflect on communicating, and managing the requirements of the FGM reporting requirements.

With consent, the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis. A coding framework was developed by the first and third authors. Transcripts were checked and coding was iteratively developed27 to incorporate emergent as well as expected themes. The analysis was supported using NVivo QSR (version 11). Lipsky’s theory of street-level bureaucracy was drawn on to help shape and interpret the findings.21

RESULTS

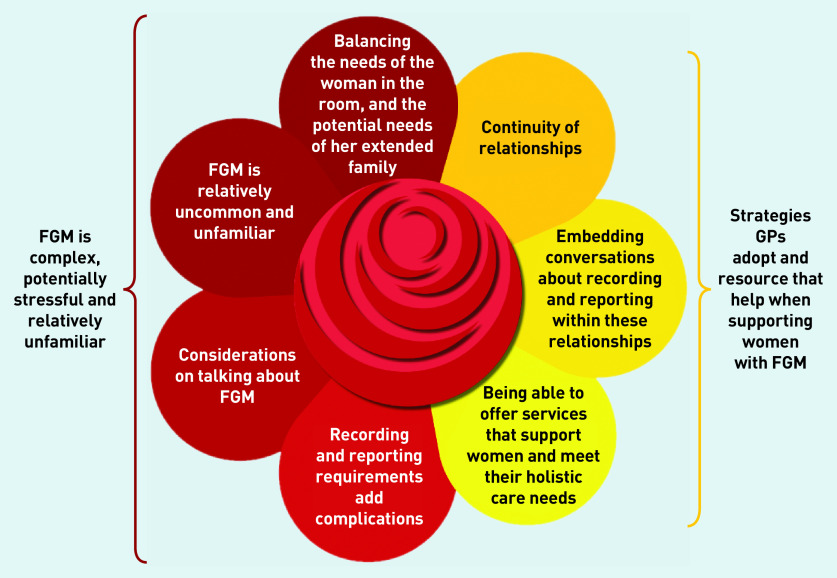

GPs reflections on the fictional scenario included descriptions of how they would respond to the scenario presented, their wider reflections on potential issues, challenges they might encounter when supporting Samara, and what they thought might help. Key themes are discussed later in the article, including responses to specifics of the consultation with Samara about FGM, as well as broader considerations and challenges of talking about FGM, managing FGM policy requirements, and what might help. These themes are discussed in relation to Lipsky’s theory. The key findings are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Themes emerging through the lens of Lipsky’s theory of street-level bureaucracy. FGM = female genital mutilation.

Female genital mutilation is complex, potentially stressful, and relatively unfamiliar

Consultation about FGM is relatively uncommon and unfamiliar for many GPs

While the recent focus on FGM and safeguarding was helpful in raising awareness, it was only a relatively recent part of formal education, as noted by GP15, who had considerable experience of primary care:

‘We didn’t talk about it; .... didn’t receive any education pretty much until quite recently, maybe in the last 5 years, and that really stemmed from being safeguarding I think, not really from general practice education, but from being safeguarding.’

(GP15)

GP3 explained that their experience of scenario-based educational discussions about FGM helped them feel ‘moderately comfortable’ about approaching the research scenario. Others noted that seeing a patient with FGM could be both complex and stressful. Towards the end of the interview, GP4 reflected that they would be ‘really worried’ and ‘really anxious about how to take it’ while some, including GP2, weren’t sure they would recognise ‘smaller forms of FGM’.

Considerations on talking about FGM

GPs often expressed concerns about how, when, and with whom they should raise the topic of FGM. This included uncertainty about the words they should or could use when talking about FGM, with some wanting guidance on what terminology would be acceptable to women and their families. The researchers heard concerns about the risks of offending women, breaching cultural sensitivities, or raising memories of a potentially traumatic experience:

‘I think I’d be worried about sort of cultural sensitivities around it and using the right terminology and, you know, you wouldn’t want to put your foot in it if you want to get a full history from somebody.’

(GP6)

In the scenario, the topic of FGM was introduced by Samara. GPs were asked whether or how they might have approached talking about FGM had Samara not raised it. Some said they thought it was more acceptable to ask about FGM in the context of a potentially related clinical problem; for example wanting to get pregnant, recurrent urinary tract infections, or where the woman asked for an intervention or support:

‘I don’t think it would necessarily be a routine question for most GPs unless it … there was a reason for it, you know period problems, that kind of thing.’

(GP16)

‘So if her agenda is already I’ve got a problem with my urinary tract then it eases you into asking those questions a lot more easily, a lot more naturally than just out of the blue. Coming up with “Well have you had FGM then?” so it would just be bizarre.’

(GP12)

While Samara spoke good English, several GPs reflected on the additional challenges that using interpreters could bring to the consultation. Such consultations were likely to be complex and require more than 10 minutes. An important consideration before commencing the conversation was who else was in the room:

‘I think I wouldn’t feel happy raising it in front of her partner or even probably her mother.’

(GP17)

‘If she’s with family then obviously that might coerce her into saying or doing things that she didn’t feel comfortable.’

(GP4)

Balancing the needs of the woman in the room, and the potential needs of her extended family

A consideration raised by many GPs was that the presenting patient may have other family members also registered with the GP practice. Therefore, seeing a woman who is affected by FGM may necessitate consideration of the potential clinical and safeguarding needs in her wider family. This could include working out how to assess potential safeguarding risks; consider assessment, contact, or review needs in the family; and potential reporting implications within the family. The impact of these considerations on the primary care relationship with the presenting patient was a concern. It was not always clear how to approach and manage these dual responsibilities:

‘If it’s just a case of managing that particular woman and her gynaecological problems ... I mean I think that’s fine you know, but it’s the whole sort of expanded risk scenario which is ... So that can balloon out of proportion and just not be manageable really.’

(GP14)

‘So I’d be thinking about the safeguarding side of things but also the legal side of things but equally my heart would be sinking because in a family you probably know the mother as well and you’ll probably be thinking “Oh no, what have I done, what have I missed? “ ‘

(GP13)

Recording and reporting requirements add complications

GPs reflected on coding FGM into the medical record, and how the FGM mandatory reporting and FGM Enhanced Dataset might affect patient–doctor relationships.

The ability to exercise discretion is central to Lipsky’s theory of street-level bureaucracy:

‘... because the accepted definitions of their tasks call for sensitive observation and judgement, which are not reducible to programmed formats.’ 21

This resonates with the disquiet expressed by a number of GPs who talked about managing the inflexible reporting and recording FGM policy requirements, including coding into the medical record.

While GPs could see advantages of coding FGM to support professional communication about safeguarding or clinical needs and avoid repeated questioning, there were evident tensions between coding for internal clinician purposes and coding for other agencies, or when records are available to patients online:

‘The whole online records and person record is being pushed from people with long-term conditions and it’s a very different issue and subset, and I think having somewhere safe to write notes for yourself and write notes for legal reasons is ... and then having to think about someone else looking at them makes it incredibly difficult.’

(GP11)

Some expressed uncertainty about coding a mother’s history of FGM into their child’s notes, raising questions about understanding who was ‘at risk’ and the confidentiality implications of coding the mother’s history onto the child’s computer record.

GPs from areas with differing prevalence of FGM had similar concerns about the consequences and difficulties of labelling a child as ‘at risk of FGM’ if her mother was adamant that she would never subject her child to FGM:

‘It feels a bit uncomfortable if you’ve had a frank discussion with the woman and she’s sort of said, you know, actually it’s not her belief and this would never happen.’

(GP9)

‘I wouldn’t want to label that child at being high risk if the mum had been dead against it, and was an advocate of not to have it, and then you put a label.’

(GP17)

Some GPs reflected that the Enhanced Dataset could reinforce the need for service provision:

‘I think in these days where they’re looking at how to allocate money, it would be hard if the data that you collect because people are opting out suggests that there isn’t the need for a service when there is, and therefore I would sell it to individuals that it’s held very securely and it’s not going to be released to third parties.’

(GP6)

However, the researchers also heard GPs concerns about the necessity or usefulness of the dataset collection or whether it constitutes a privacy breach, questioning the legitimacy of service norms where they conflict with professional discretion:

‘If it’s a safeguarding issue it’s a safeguarding issue and I’ll deal with that appropriately. But I don’t think sending all my women’s personal information somewhere is actually helping that at all really.’

(GP13)

‘I’ve got severe reservations about the necessity for that information to go, and the breach of confidentiality which I fear it may be.’

(GP1)

Advocacy and making patients’ needs primary are explicitly required in medical ethics and professional guidance. Lipsky writes that this may be experienced as:

‘... incompatible with their need to judge and control clients for bureaucratic purposes.’ 21

The authors consider that this tension resonates with these GPs’ concerns that the Enhanced Dataset could complicate or deter conversations about FGM:

‘I think it complicates the matter in terms of, you know, when you’ve got a woman who’s presented with what is a, you know very sensitive issue, and one that she’s potentially spent a lot of time umming and aahing over whether to disclose it or not, to then have to […] do all of that consultation and then go “Well actually, just to let you know we do have to report this information” and how that might then make her feel.’

(GP8)

GPs’ accounts highlighted tensions between appearing to be a ‘ law-keeper’ (GP10) in addition to their caring role, describing concerns about the potential impact on doctor–patient relationships:

‘There have been sort of mixed messages I think for some of the patients about [...] our role as GPs to support them, but the sort of requirements on us also to be scrutineers …’

(GP5)

‘You want to be able to have a strong relationship with your patient unless there’s a really threatening thing like you’re getting involved with and your hands are tied about whether you can do that or not. And so, I think that certainly it has the potential to risk the doctor–patient relationship because they came to you in confidence and that hasn’t necessarily been how it’s ended up.’

(GP10)

Strategies and resources to support women with FGM

Continuity of relationship

Embedded within GPs descriptions of how they would approach Samara’s scenario were accounts of what they valued as core components of being a GP. The GP should be the ‘ first port of call ’ (GP13), know the wider family, the locality, and offer ongoing relationships and support. While FGM might be relatively unfamiliar, the following experienced GP noted that patient-centred consulting skills would be transferable:

‘This feels like a scenario that has to be handled very carefully, but it’s not … that’s our sort of bread and butter as GPs, and just going with the patient and moving things forward at their pace, that’s what we do.’

(GP7)

Developing trusting relationships could provide a framework that would support the opportunity to both care for the woman and safeguard her and her family.

GPs voiced concerns that mandated reporting could adversely impact these relationships:

‘It would just be building a relationship ... and they would trust you. And then they’d also tell you the truth. You can only go on what someone tells you, and if they don’t trust you and say “No, no” but then they disappear off. You’ve kind of blown it, and you’ve blown an opportunity.’

(GP17)

‘You know there’s that mutual trust thing that is quite difficult to maintain if you’re suddenly going to start talking about reporting and involving other members of the family.’

‘You want to maintain your relationship with her in order to have her best interests at heart, but also you want to do a risk assessment in terms of her sister as well.’

(GP12)

Embedding conversations about recording and reporting within these relationships

GPs described how they would endeavour to make the policy requirements seem acceptable to Samara. This resonates with Lipsky’s observations that:

‘... one important way in which street-level bureaucrats experience their work is in their struggle to make it more consistent with their strong commitments to public service and the high expectations they have for their chosen careers,’ 21

And:

‘... they believe themselves to be doing the best they can under adverse circumstances, and they develop techniques to salvage service and decision-making values within the limits imposed upon them.’ 21

Strategies suggested by GPs included framing the discussion in the context of their safeguarding duties, showing documents to prove that the reporting was not their idea or decision, or explaining that providing data will help ensure the provision of services:

‘You lay on the table what your duties are and why, that it’s for the good of society in the population at large and it’s to protect people and it’s the idea of collecting data to look at incidence.’

(GP3)

Another strategy was embedding required conversations within established patient–doctor relationships:

‘I think that would happen at a time at which I’d felt that trust had been established that we could have an open conversation without jeopardising other aspects of the doctor–patient relationship.’

(GP5)

Being able to offer services that support women and meet their holistic care needs

GPs were asked which services they thought would support them when they were caring for women and families who may be affected by FGM. They described wanting access to culturally sensitive services that would offer supportive care and advice across the woman and her family’s life-course, including their safeguarding, physical, and mental health needs. GPs with experience of working in areas with access to services described the difference that knowing there was a pathway through which the woman’s needs would be met could make to their confidence in raising the subject of FGM:

‘Because of the exposure and knowledge that we’ve got support there, it’s much easier to bring up. I suspect if I had less awareness and I wasn’t sure what there was to support somebody, it would be a really challenging issue to raise with all the associated potential distress and fallout, yet not have anywhere to go with that.’

(GP5)

DISCUSSION

Summary

FGM is experienced as complex to manage in primary care, with challenges including consideration of how and when to talk about FGM, and how to meet the potential needs of both the woman who presents and her family. Managing FGM reporting and recording brings additional tensions into the consultation. Access to specialist services and education about more than safeguarding were identified as important resources to support GPs caring for patients with FGM.

Strengths and limitations

As far as the authors are aware, this is the first study of the issues GPs consider when managing FGM in primary care. It contributes the perspectives of front-line clinicians on the policies of mandatory reporting and the FGM Enhanced Dataset. Using a qualitative approach and a fictional scenario, the authors sought to create an open space for GPs thoughts and reflections. GPs with a range of exposure to FGM were interviewed, including those with experience of seeing women with FGM never, rarely, and often. The present study included GPs who were safeguarding leads, and others who were not, in five cities, two of which had a local specialist clinic.

All 17 GPs were interested in participating in a conversation about managing FGM; all but one were women. The authors therefore cannot, and do not, suggest that these findings are numerically representative of the GP population, but did achieve considerable variation of experience and views in the sample.

GPs confront a range of issues which Lipsky’s social theory helps us understand as reflecting a wider issue in the tensions that GPs experience in relation to mandatory reporting.

Comparison with existing literature

The authors are not aware of any previous work considering GPs’ perspectives on supporting women with FGM in primary care, including the impacts of recent English policy. The existing FGM literature derives predominantly from obstetric and maternity settings. Some of the present findings resonate with these accounts, for example the challenges in talking about FGM including the use of interpreters,28–31 but the authors also heard about issues specific to primary care. In maternity care, asking about FGM will usually be immediately relevant to the woman’s current clinical care needs, and in the context of a clinical relationship that rarely outlasts the duration of pregnancy. In contrast, there is value in developing and maintaining ongoing relationships over the life-course in primary care, and a requirement to balance the needs of the woman who is presenting and her wider family, if registered at the same practice. GPs utilising trusting relationships with families within a strategy to facilitate care and safeguarding has been previously described.32

Though well established, street-level bureaucracy is an under used theoretical model in general practice.22 Previous work has used this theory to understand primary care responses to National Service Frameworks24 and policies to reduce unscheduled care.23 The presented analysis is supported by its resonance with Lipsky’s theory, notably the disquiet described at the removal of professional discretion.

The central findings presented here are the tensions expressed by GPs who perceived that policy required them to act as ‘law-keepers’ while also patient advocates, and GP concerns that these requirements could negatively impact on perceptions of trust, confidentiality and on patient–doctor relationships. Evidence from community settings suggests these fears may be well founded, with community research demonstrating that policies can deter members of FGM-affected communities from accessing services.14,16 Concerns have been raised that the response to FGM is ‘disproportionate’ in comparison with other child safeguarding,33 and of the lack of evaluation for mandatory reporting for FGM.34 Mandatory reporting is being considered in other areas of safeguarding in the UK.35,36

Beyond FGM, policies that require data sharing (or where there are fears that data sharing will occur) can deter patients, notably vulnerable patients, from accessing care and services.37–39 As with the GPs in the present study, doctors have voiced concerns about requirements to enact policies that they consider will compromise their professional ethos or relationships with their patients37,40–42 including through organisations like Docs Not Cops (http://www.docsnotcops.co.uk) and medact.43

Implications for research and practice

Making FGM specialist clinics available wherever there is need should be a resource priority. With input including GP and community expertise, educational resources including holistic aspects of care and safeguarding could be developed for primary care.

There is a pressing need to develop understanding about how the management of mandated reporting and data sharing impact on trust and communication in primary care. Adequately evaluating such policies is a research priority in the context of consultations on the expansion of mandatory reporting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Frances Griffiths, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick.

Funding

Sharon Dixon was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) In-Practice Fellowship (2016–2018) during this research project. Professor Sue Ziebland is an NIHR Senior Investigator. Lisa Hinton was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by Oxford University and the Health Research Authority (reference number: R46851/RE002, IRAS number 238807, REC reference: 18/HRA/1601).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Sharon Dixon is a trustee of Oxford Against Cutting. Following this project, Sharon Dixon has acted as the RCGP College Representative for FGM. Sue Ziebland and Lisa Hinton have no competing interests to declare.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Female genital mutilation. 2020 https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 2.Reisel D, Creighton SM. Long term health consequences of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Maturitas. 2015;80(1):48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations Children’s Fund . Female genital mutilation/cutting: a global concern. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macfarlane A J, Dorkenoo E. Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: National and local estimates. London: City University London in association with Equality Now; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahase E. NHS opens eight walk-in FGM clinics across England. BMJ. 2019;366:l5552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Home Office Girl Summit 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/girl-summit-2014 (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 7.Department for Education; Home office Mandatory reporting of female genital mutilation: procedural information. 2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mandatory-reporting-of-female-genital-mutilation-proceduralinformation (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 8.Department of Health. Health and Social Care Information Centre FGM Prevention Programme Understanding the FGM Enhanced Dataset — updated guidance and clarification to support implementation. 2015 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/461524/FGM_Statement_September_2015.pdf (accessed 12 Aug 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Digital SCCI2026: Female Genital Mutilation Enhanced Dataset. 2018 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/information-standards/information-standards-and-data-collections-including-extractions/publications-and-notifications/standards-and-collections/scci2026-femalegenital-mutilation-enhanced-dataset (accessed 24 Aug 2020).

- 10.Bewley S, Kelly B, Darke K, et al. Mandatory submission of patient identifiable information to third parties: FGM now, what next? BMJ. 2015;351:h5146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathers N, Rymer J. Mandatory reporting of female genital mutilation by healthcare professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2015 doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dixon S. The FGM enhanced dataset: how are we going to discuss this with our patients? Br J Gen Pract. 2015 doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.McCartney M. Margaret McCartney: Disrespecting confidentiality isn’t the answer to FGM. BMJ. 2015;351:h5830. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlsen S, Carver N, Mogilnicka M, Pantazis C. When safeguarding becomes stigmatising A report on the impact of FGM-safeguarding procedures on people with a Somali heritage living in Bristol. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035039. https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/files/187177083/Karlsen_et_al_2019_When_Safeguarding_become_Stigmatising_Final_Report.pdf (accessed 12 Aug 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlsen S, Carver N, Mogilnicka M, Pantazis C. ‘Putting salt on the wound’: a qualitative study of the impact of FGM-safeguarding in healthcare settings on people with a British Somali heritage living in Bristol, UK. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e035039. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plugge E, Adam S, el Hindi L, et al. The prevention of female genital mutilation in England: what can be done? J Public Health. 2019;41(3):e261–e266. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NHS Digital Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Enhanced Dataset – April 2019 to March 2020, experimental statistics, Annual report. 2020 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/female-genital-mutilation/april-2019---march-2020 (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 18.British Medical Association Pressures in general practice. 2020 https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/pressures-in-general-practice (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 19.Dixon S, Agha K, Ali F, et al. Female genital mutilation in the UK-where are we, where do we go next? Involving communities in setting the research agenda. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s40900-018-0103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zurynski Y, Sureshkumar P, Phu A, Elliot E. Female genital mutilation and cutting: a systematic literature review of health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and clinical practice. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015;15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s12914-015-0070-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipsky M. Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service. 2nd edn. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper MJ, Sornalingam S, O’Donnell C. Street-level bureaucracy: an underused theoretical model for general practice? Br J Gen Pract. 2015 doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Drinkwater J, Salmon P, Langer S, et al. Operationalising unscheduled care policy: a qualitative study of healthcare professionals’ perspectives. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X664243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Checkland K. National Service Frameworks and UK general practitioners: street-level bureaucrats at work? Sociol Health Illn. 2004;26(7):951–975. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9889.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashdown HF, Räisänen U, Wang K, et al. Prescribing antibiotics to ‘at-risk’ children with influenza-like illness in primary care: qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011497. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziebland S, Graham A, McPherson A. Concerns and cautions about prescribing and deregulating emergency contraception: a qualitative study of GPs using telephone interviews. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):449–456. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman D. Doing Qualitative Research. Fourth Edition. London: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clayton-Hathaway K. Oxford against cutting. Oxford: Healthwatch; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson A, Homer CS, Turkmani S, et al. A systematic review of doctors’ experiences and needs to support the care of women with female genital mutilation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazar JN, Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Davis OI, Shipp MP. Providers’ perceptions of challenges in obstetrical care for Somali women. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:149640. doi: 10.1155/2013/149640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans C, Tweheyo R, McGarry J, et al. Crossing cultural divides: a qualitative systematic review of factors influencing the provision of healthcare related to female genital mutilation from the perspective of health professionals. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0211829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodman J, Rafi I, de Lusignan S. Child maltreatment: time to rethink the role of general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2014 doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X681265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Creighton SM, Samuel Z, Otoo-Oyortey N, Hodes D. Tackling female genital mutilation in the UK. BMJ. 2019;364:l15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerry F, Rowland A, Fowles S, et al. Failure to evaluate introduction of female genital mutilation mandatory reporting. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(8):778–779. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Home Office Preventing and tackling forced marriage. 2018 https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/preventing-and-tackling-forced-marriage (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 36.Independent Inquiry Child Sexual Abuse Mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse. 2019 https://www.iicsa.org.uk/research-seminars/mandatory-reportingchild-sexual-abuse (accessed 12 Aug 2020).

- 37.Hiam L, Steele S, McKee M. Creating a ‘hostile environment for migrants’: the British government’s use of health service data to restrict immigration is a very bad idea. Health Econ Policy Law. 2018;13(2):107–117. doi: 10.1017/S1744133117000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiam L. Grenfell survivors shouldn’t be afraid to go to hospital. BMJ. 2017;358:j3292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter JL, Milner A. Tuberculosis: looking beyond ‘migrant’ as a category to understand experience; better health briefing 44. London: Race Equality Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Emam K, Mercer J, Moreau K, et al. Physician privacy concerns when disclosing patient data for public health purposes during a pandemic influenza outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):454. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salisbury H. Helen Salisbury: a hostile environment in the NHS. BMJ. 2019;366:l5328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papageorgiou V, Wharton-Smith A, Campos-Matos I, Ward H. Patient data-sharing for immigration enforcement: a qualitative study of healthcare providers in England. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033202. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medact Our work. 2016 https://www.medact.org/our-work/ (accessed 12 Aug 2020).