Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate perceptions of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional survey of 200 women receiving medication for opioid use disorder in Vermont.

Results:

A considerable proportion of women receiving medication for opioid use disorder in Vermont reported previous use of an IUD (40%) and/or a subdermal contraceptive implant (16%); the majority of prior LARC users were satisfied with their IUD (68%) or their implant (74%). Of the 38% of participants who had never considered IUD use, 85% percent (64/75) said that they knew nothing or only a little about IUDs. Of the 61% of participants who had never considered an implant, 81% percent (98/121) said that they knew nothing or only a little about the contraceptive method. The most commonly reported reasons for a lack of interest in the IUD and/or implant were concerns about side effects and preference for a woman-controlled method.

Conclusions:

Gaps in LARC knowledge are common among those who have not used LARCs and concerns about side effects and preferences for a woman-controlled method limit some women’s interest in these contraceptives. Additionally, reasons for dissatisfaction among past users are generally similar for IUD and implant and include irregular bleeding and having a bad experience with the method.

Implications:

Efforts to increase awareness of LARC methods among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder should address concerns about side effects and reproductive autonomy and encourage satisfied LARC users to share their experiences with their social networks.

Keywords: Long-acting reversible contraception, Intrauterine device, Implant, Opioid use disorder, Opioid agonist treatment, Unintended pregnancy

1. Introduction

A dramatic rise in opioid use among pregnant women [1] has led to increasing concerns about in utero exposure to opioids and associated adverse health and economic outcomes [2]. Recently, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics with the support of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have called for a public health response to decrease the incidence of in utero opioid exposure [3, 4]. Noting high rates of unintended pregnancy among women who use opioids (>80%) [5], proposed strategies have called for increasing access to effective contraception.

The intrauterine device (IUD) and contraceptive implant (together, categorized as long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods), are the most effective forms of reversible contraception [6]. Complications are rare with LARC use [7, 8] and continuation rates are higher than with shorter acting methods [9, 10]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of current LARC use in the United States remains lower (7%) than rates of use of less effective methods such as pills (16%) [11].

Among women with substance use disorders, very limited data suggest rates of current LARC use [12, 13] are similar to rates in the general population (12% vs 7%). However, Matusiewicz et al. (2017) recently conducted a study to understand potential barriers to LARC use in this population [14] and results suggest that women receiving medication for opioid use disorder may have unique reasons for not using LARC. Because Matusiewicz et al. used a limited list of potential barriers, the primary purpose of this study was to examine a wider range of potential barriers to LARC use among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder and to distinguish barriers to LARC initiation among those who had never used a LARC separately from perceptions of prior LARC users.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

We recruited participants on 25 days between November 21, 2017 and January 25, 2018 from a Burlington, VT clinic that provided outpatient medication treatment for opioid use disorder to about 1000 patients, including approximately 400 women aged 18–44 years who were eligible to participate. Refusal to participate was rare; rather, the extended recruitment period was a function of research staff availability. Participants provided verbal consent, then completed the survey on an electronic tablet via REDCap [15]. Participants received compensation in the form of a $20 gift card. The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

2.2. Measures

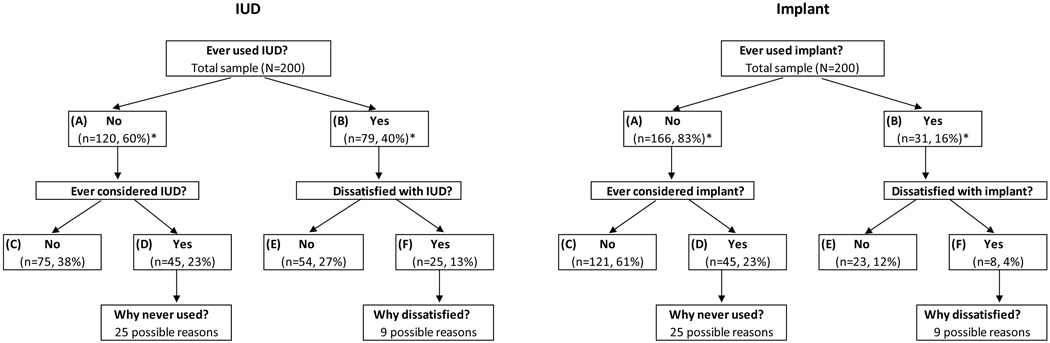

We assessed knowledge, attitudes, experiences, and perceived barriers to LARCs with questions adapted from Hall et al. (2016) [16]. We asked all participants how much they felt they knew about both IUDs and implants. We then asked participants if they had ever used an IUD and/or an implant (Figure 1). We then asked those who reported they had never used an IUD or implant, if they had ever considered using either method. If they had, we further asked, “Which of the following reasons have ever prevented you from using” an IUD or implant. Participants were asked to review a list of 25 reasons modified from Hall et al. [16] (Table 2). If a participant selected “other,” we asked her to specify the other reason. Women could select multiple reasons for not using an IUD or implant. We then asked, “Which of those reasons is the number one reason why you would not use that method?” We did not ask women who had never considered LARC use about barriers to IUD or implant use.

Figure 1.

Experience with IUD and implant use among 200 women receiving medication for opioid use disorder in Vermont U.S. in 2017 and 2018.

*Note missing data from one participant regarding IUD use and three participants regarding implant use.

Table 2.

Reasons for Deciding Against LARC Use among Women Receiving Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Vermont U.S. in 2017 and 2018

| Barrier to use |

Main barrier to use |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUD n=45a n (%) |

Implant n=45b n (%) |

p-value |

IUD n=45a n (%) |

Implant n=45b n (%) |

p-value |

|

| Individual level | ||||||

| Do not want a foreign object in your body | 26 (58%) | 20 (44%) | .33 | 4 (9%) | 9 (20%) | .32 |

| Would rather use a method that you are in control of stopping and starting | 27 (60%) | 24 (53%) | .45 | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Do not know enough about that to feel comfortable using it | 12 (27%) | 16 (36%) | .53 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about pain with having that method inserted | 26 (58%) | 23 (51%) | .45 | 6 (13%) | 4 (9%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about side effects (i.e. weight gain, mood changes) | 30 (67%) | 24 (53%) | .04 | 3 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about serious health problems (i.e. blood clots, cancer) | 23 (51%) | 19 (42%) | .33 | 3 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Prefer not to have a method placed in that location in your body | 22 (49%) | 21 (47%) | 1.00 | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about infertility | 7 (16%) | 10 (22%) | .78 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about irregular bleeding or spotting | 16 (36%) | 9 (20%) | .19 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Worried about that method interfering with your sexual life or sexual enjoyment | 12 (27%) | 6 (13%) | .11 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Not eligible for that method because you have never given birth | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | .56 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Not eligible for that method because you have had gynecological problems | 3 (7%) | 1 (2%) | .56 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Health systems level | ||||||

| Worried about cost or insurance coverage | 8 (18%) | 6 (13%) | .68 | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Do not want to go in to the clinic multiple times for counseling or insertion | 16 (36%) | 8 (18%) | .08 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| You have to go to a health care provider to have that method inserted or removed | 19 (42%) | 16 (36%) | .85 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.00 |

| A health provider says you should not use that method | 4 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 1.00 | 1 (2%) | 3 (7%) | 1.00 |

| You do not have access to a health care facility that can give you that method | 4 (9%) | 5 (11%) | 1.00 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Community/interpersonal level | ||||||

| You have not been in a long-term relationship | 4 (9%) | 4 (9%) | 1.00 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Your friends or relatives have had bad experiences with that method | 20 (44%) | 17 (38%) | .71 | 11 (24%) | 8 (18%) | .82 |

| You have heard bad things about that method on TV or on the Internet | 17 (38%) | 12 (27%) | .19 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Your religion prevents you from using that method | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1.00 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| You do not have sex with men | 8 (18%) | 4 (9%) | .45 | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1.00 |

| You cannot get pregnant | 11 (24%) | 9 (20%) | 1.00 | 4 (9%) | 4 (9%) | 1.00 |

| You want to get pregnant | 4 (9%) | 5 (11%) | 1.00 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| Other reason | 0 (0%)a | 1 (2%)b | 1.00 | 1 (2%)b | 2 (4%)c | 1.00 |

Note.

n=28 considered both IUD and implant and n=17 considered only IUD.

n=28 considered both IUD and implant and n=17 considered only implant.

Three participants reported “other” reasons, all of which were recategorized into the existing list of barriers.

Four participants listed “other” reasons for deciding against an implant and three of these were recategorized into existing categories.

Four participants listed “other” reasons for their main barrier to implant initiation and two of these were recategorized. Columns IUD and Implant under “Barrier to use” do not sum to 45 (100%) because participants could select more than one reason. Barriers are the same as those in Hall et al. (2016) except that we included three additional reasons, modified one, and removed one. Added reasons were: “You cannot get pregnant,” “You want to get pregnant,” and “You do not have sex with men.” To better reflect modern media, we changed “newspaper” to “internet” for the reason, “You have heard bad things about that method on TV or in the newspaper.” Because, by definition, this subset of participants never used the method, we removed the reason, “You had a bad experience with that method already.”

When women reported prior LARC use, we asked them to rate their satisfaction with the contraceptive method using a five-item scale ranging from extremely satisfied to extremely dissatisfied. We then asked those who were either slightly or extremely dissatisfied about 9 possible reasons for dissatisfaction, modified from Hall et al. (2016) [16], with the option to specify any “other” reason. Women could select multiple reasons for being dissatisfied with the IUD or implant and were then asked to select their number one reason for dissatisfaction.

Three of the authors reviewed all “other” reasons provided by participants. If there was consensus between at least two of the three that the response belonged within an existing category, we reclassified it into that category. If not, the response remained in the “other” category.

We compared reasons for not previously using an IUD or implant with a z-test that accounts for the partial overlap in the two groups [17, 18], as some participants had considered using both IUD and implant and others considered only one of the two methods. The z-test corresponds to a weighted average of the exact McNemar’s test for correlated proportions and the continuity corrected chi square test for independent proportions. The same test was used for comparing reason for dissatisfaction among those who had used an IUD or implant. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

Participant characteristics (N=200) are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants were between the ages of 25 to 38, white, unemployed, and heterosexual. About half of participants reported having a high school degree and being in a long-term partnered relationship (including married/engaged). Participants prior use of LARC is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Women Receiving Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Vermont U.S. in 2017 & 2018

| Characteristic |

N=200 n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 8 (4%) |

| 25–31 | 74 (37%) |

| 32–38 | 86 (43%) |

| 39–44 | 32 (16%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 192 (96%) |

| Other | 8 (4%) |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school degree | 39 (20%) |

| High school degree | 96 (48%) |

| More than a high school degree | 65 (33%) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married/engaged | 45 (23%) |

| Living with partner | 48 (24%) |

| Long-term relationship | 41 (21%) |

| Casual relationship | 21 (11%) |

| None | 45 (23%) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 76 (38%) |

| Unemployed | 124 (62%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 147 (74%) |

| Gay/lesbian | 6 (3%) |

| Bisexual | 41 (21%) |

| Unsure | 6 (3%) |

3.1. Women Who Never Used or Considered an IUD or an Implant

One hundred and twenty women (60% of the total sample) reported never using an IUD; of these women, 75 (38% of the total sample) reported never having considered IUD use. Of these women, 85% percent (64/75) said that they knew nothing or only a little about IUDs.

Implant use was less common; 166 women (83% of the total sample) reported never using an implant; of these women, 121 women (61% of the total sample) reported never considering using an implant. Of these women, 81% percent (98/121) said that they knew nothing or only a little about implants.

3.2. Reasons for Deciding Against LARC Among Women Who Considered It

Among women who had considered but decided against LARC use, rankings of concerns related to IUD and implant use were similar (Table 2). Across methods, the most frequently cited reasons were concerns about side effects, preference for a method they are in control of stopping, and concern over pain with having the contraceptive placed (Table 2). However, worries about side effects (i.e. weight gain, mood changes) were more common with the IUD (n=30, 67%) than implant (n=24, 53%), p = .04.

When we asked participants to select a single main reason for not initiating a LARC method, rankings were similar (Table 2). Across methods, they most frequently reported that friends or relatives had had a bad experience with that method (Table 2).

3.3. Women Who had Used a LARC Method

Most women who had used an IUD or implant were satisfied with the method (Figure 1). The 25 participants who had been dissatisfied with their use of an IUD and the 8 who had been dissatisfied with use of an implant identified a variety of reasons detailed in Table 3. In this small sample, reasons for dissatisfaction with the IUD and implant were generally similar, but irregular bleeding and spotting was more often problematic for implant (n=5, 63%) than IUD (n=3, 12%) users, p = .01.

Table 3.

Self-Reported Reasons for Dissatisfaction with Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Among 31 Women Receiving Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Vermont U.S. in 2017 and 2018

| Reason for dissatisfaction |

Main reason for dissatisfaction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUD n=25a n (%) |

Implant n=8b n (%) |

p-value |

IUD n=25a n (%) |

Implant n=8b n (%) |

p-value |

|

| Individual level | ||||||

| You did not like having a foreign object in your body | 5 (20%) | 1 (13%) | 1.00 | 1 (4%) | 1 (13%) | .88 |

| You did not like that you were not in charge of stopping and starting the method | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | .86 | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| You were experiencing side effects (i.e. weight gain, mood changes) | 12 (48%) | 2 (25%) | .72 | 4 (16%) | 1 (13%) | 1.00 |

| You were worried about serious health problems (i.e. blood clots, cancer) | 4 (16%) | 0 (0%) | .67 | 1 (4%) | 1 (13%) | 1.00 |

| You were worried about infertility | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | .86 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| You were experiencing irregular bleeding or spotting | 12 (48%) | 5 (63%) | .86 | 3 (12%) | 5 (63%) | .01 |

| The method interfered with your sexual life or sexual enjoyment | 7 (28%) | 0 (0%) | .31 | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| You were having a bad experience with the method | 18 (72%) | 2 (25%) | .06 | 10 (40%) | 0 (0%) | .13 |

| Other reason | 4 (16%)c | 0 (0%) | .67 | 2 (8%)d | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

Note.

n=23 dissatisfied with only IUD and n=2 dissatisfied with both IUD and implant.

n=6 dissatisfied with only implant and n=2 dissatisfied with both IUD and implant.

Ten participants selected “other” reasons for IUD dissatisfaction when they could select all that apply and six of the ten were recategorized into existing reasons.

Four participants listed “other” reason as their main reason for IUD dissatisfaction and two of the four were recategorized into existing reasons. Columns IUD and Implant under “Reason for dissatisfaction” do not sum to 25 (100%) or 8 (100%), respectively, because participants could select more than one reason. Barriers are the same as those in Hall et al. (2016) except that we changed the tense from present tense to past tense and excluded reasons that were unrelated to method satisfaction.

4. Discussion

This study of women receiving medication for opioid use disorder in Vermont found high rates of lifetime LARC use, but also opportunities to increase awareness of subdermal implants as well as IUD for some women in this population. Toolkits that provide guidance on how to counsel women about common side effects with LARC use may be helpful [19]. However, concerns about loss of reproductive autonomy are harder to address and require a trusting relationship between patients and clinicians [20]. This may be a particular challenge for women receiving medication for opioid use disorder as patients with substance use disorders report being stigmatized by healthcare providers [21–23], and it is common for healthcare professionals to express negative attitudes about patients with substance use disorders [24]. The high rates of trauma among individuals with substance use disorders [25, 26] may also contribute to concerns about reproductive autonomy. Trauma-informed care, which emphasizes principles like individual choice and control [27], is recommended to help optimize the relationship between women and reproductive health providers, improve health outcomes, and decrease the long-term consequences of trauma [28]. It is important that providers be mindful of these women’s vulnerability and make extra efforts to use non-coercive counseling [e.g., 29]. Informing women of the option of IUD self-removal may also be useful [30].

Concerns about pain with contraceptive placement are particularly important to discuss with women receiving medication for opioid use disorder who may have increased pain as a function of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, a condition where chronic use of opioids makes patients hypersensitive to painful stimuli [31–33]. Increasing awareness among family planning providers of opioid-induced hyperalgesia and options to improve procedural pain control for women with opioid use disorder, may make this population more willing to consider LARC.

Our findings align with prior research that has shown that negative LARC stories can deter initiation [34]. Some have proposed the development of interventions that encourage satisfied users to share information about their positive experiences [35]; this may be an especially effective approach among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder given sometimes fraught relationships with their providers.

A mixed-methods study published recently also examined barriers to LARC use among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder [36]. They interviewed 50 women using some of the same items as the present study, but items were grouped into larger themes for reporting and results reflected the sample as a whole and were not broken down by past use or considerations of use. Nevertheless, the three most common themes were: 1) fear of complications, a theme that included fear of physical side effects like bleeding and pain; 2) family, friend, and acquaintance reports of primarily bad experiences with the methods; and 3) discomfort with the idea of a foreign object being inserted into their body. Thus, despite differences in methodology, the overall results are quite consistent across these two studies.

There are some limitations to this study that should be noted. First, participants were not selected at random; instead we used a convenience sample that may have been subject to response bias. Second, the generalizability of our findings is limited as the majority of our sample was White and race and ethnicity have been shown to impact women’s preferences for features of contraceptive methods [37, 38]. Third, there was a limited sample size, especially regarding the subsample of women who were dissatisfied with their implant experience. Therefore, these results should be treated as hypothesis generating, but may offer insights into future steps to reduce rates of undesired pregnancy among women receiving medication for opioid use disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01DA036670, R01DA047867, T32DA07242, and P20 GM103644. The sponsor had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Footnotes

Catalina N. Rey, Gary J. Badger, Heidi S. Melbostad, Deborah Wachtel, Stacey C. Sigmon, Lauren K. MacAfee, Anne K. Dougherty, and Sarah H. Heil declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, Bohm MK, Callaghan WM. Opioid use disorder documented atdelivery hospitalization — United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:845–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographicdistribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: Unites States 2009 to 2012. J. Perinatol 2015;35:650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ko JY, Wolicki S, Barfield WD, Patrick SW, Broussard CS, Yonkers KA, et al. CDCgrand rounds: Public health strategies to prevent neonatal abstinence syndrome. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2017;66:242–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Patrick SW, Schiff DM, AAP COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION. A public health response to opioid use in pregnancy. Pediatrics 2017;139(3):e20164070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, Kaltenbach K, Coyle M, Fischer G, et al. Unintended pregnancyin opioid-abusing women. J SubstAbus Treat 2011;40:199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Romano MJ, Toye P, Patchen L. Continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptivesamong Medicaid patients. Contraception 2018;98(2):125–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stoddard A, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Efficacy and safety of long-acting reversiblecontraception. Drugs 2011;71:969–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Agostini A, Godard C, Laurendeau C, Zoubir AB, Lafuma A, Lévy-Bachelot L, Gourmelen J, Linet T Two year continuation rates of contraceptive methods in France: a cohort study from the French national health insurance database. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 2018:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hubacher D, Spector H, Monteith C, Chen PL. Not seeking yet trying long-acting reversiblecontraception: a 24-month randomized trial on continuation, unintended pregnancy and satisfaction. Contraception 2018;97:524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS data brief 2014;173:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Meschke LL, McNeely C, Brown KC, Prather JM. Reproductive health knowledge,attitudes, and behaviors among women enrolled in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. J Women’s Health 2018;10:1215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Poulton G, Parlier AB, Scott KR, Fagan EB, Galvin SL. Contraceptive choices forreproductive age women at methadone clinics in Western North Carolina. MaAHEC Online J Res 2015;2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Matusiewicz AK, Melbostad HS, Heil SH. Knowledge of and concerns about long-actingreversible contraception among women in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Contraception 2017;96:365–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic datacapture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hall KS, Ela E, Zochowski MK, Caldwell A, Moniz M, McAndrew L, Steel M, Challa S,Dalton VK, Ernst S. “I don’t know enough to feel comfortable using them:” Women’s knowledge of and perceived barriers to long-acting reversible contraceptives on a college campus. Contraception 2016;93:556–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Samawi HM, Vogel R. Tests of homogeneity for partially matched-pairs data. StatisticalMethodology 2011;8(3):304–13. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Whitlock MC. Combining probability from independent tests: the weighted z-method issuperior to Fisher’s approach. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2005;18(5):1368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Toolkits. Managing Side Effects for IUDs. Available at: https://toolkits.knowledgesuccess.org/toolkits/iud/managing-side-effects-iuds. Accessed on 11/22/2019.

- [20].Zeal C, Higgins JA, Newton SR. Patient-perceived autonomy and long-acting reversiblecontraceptive use: a qualitative assessment in a Midwestern, university community. BioReasearch Open Access 2018;71:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Armstrong KA, Kenen R, Samost L. Barriers to family planning among patients in drugtreatment programs. Family Planning Perspectives 1991;23(6):264–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neale J, Tompkins C, Sheard L. Barriers to accessing generic health and social careservices: a qualitative study of injecting drug users. Health and Social Care in the Community 2008;16(2):147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sleeper JA, Bochain SS. Stigmatization by nurses as perceived by substance abuse patients: A phenomenological study. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2013;3(7):92–8. [Google Scholar]

- [24].van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Wheeghel J, Garretson HFL. Public opinion onimposing restrictions to people with an alcohol- or drug addiction: a cross-sectional survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:2007–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Reynolds M, Mezey G, Chapman M, Wheeler M, Drummond C, Baldacchino A. Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;77(3):251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Driessen M, Schulte S, Luedecke C, Schaefer I, Sutmann F, Ohlmeier M, et al. Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: a multi-center study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(3):481–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept ofTrauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [28].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Sexual assault. ACOG CommitteeOpinion No. 777. ObstetGynecol 2019;133:e296–302. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical Guidance forTreating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants. Available at: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma18-5054.pdf Accessed on 11/22/2019.

- [30].Foster DG, Grossman D, Turok DK, Peipert JF,Prine L, Schreiber CA, Jackson AV, Barar RE, Schwarz EB Interest in and experience with IUD self-removal. Contraception 2014;90(1):54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Athanasos P, Ling W, Bochner F, White JM, Somogyi AA. Buprenorphine maintenancesubjects are hyperalgesic and have no antinociceptive response to a very high morphine dose. Pain Medicine 2019;20(1):119–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Athanasos P, Smith CS, White JM, Somogyi AA, Bochner F, Ling W. Methadonemaintenance patients are cross tolerant to the antinociceptive effects of very high plasma morphine concentrations. Pain 2006;120:267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Compton P, Canamar CP, Hillhouse M, Ling W. Hyperalgesia in heroin dependent patients and the effects of opioid substitution therapy. The Journal of Pain 2012;13(4):401–09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Brown BP, Chor J, Hebert LE, Webb ME, Whitaker AK. Shared negative experiences of long-acting reversible contraception and their influence on contraceptive decision-making: a multi-methods study. Contraception 2019;99:228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Anderson N, Steinauer J, Valente T, Koblentz J, Dehlendorf C. Women’s socialcommunication about IUDs: A qualitative analysis. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2014;46(3):141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Smith C, Morse E, Busby S. Barriers to reproductive healthcare for women with opioid usedisorder. J Perinat NeonatNurs 2019;33(2): E3–E11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Branum AM, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among U.S.women aged 15–44. NCHS Data Brief 2015;188:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jackson AV, Karasek D, Dehlendorf C, Foster DG. Racial and ethnic differences inwomen’s preferences for features of contraceptive methods. Contraception 2016;93(5):406–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]