To the Editor: CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)–based diagnostic tests1,2 collectively provide a nascent platform for the detection of viral and bacterial pathogens. Methods such as SHERLOCK (specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking), which typically use a two-step process (target amplification followed by CRISPR-mediated nucleic acid detection),1,2 have been used to detect SARS-CoV-2.3 These approaches, however, are more complex than those used in point-of-care testing because they depend on an RNA extraction step and multiple liquid-handling steps that increase the risk of cross-contamination of samples.

Here, we describe a simple test for detection of SARS-CoV-2. The sensitivity of this test is similar to that of reverse-transcription–quantitative polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-qPCR) assays. STOP (SHERLOCK testing in one pot) is a streamlined assay that combines simplified extraction of viral RNA with isothermal amplification and CRISPR-mediated detection. This test can be performed at a single temperature in less than an hour and with minimal equipment.

The integration of isothermal amplification with CRISPR-mediated detection required the development of a common reaction buffer that could accommodate both steps. To amplify viral RNA, we chose reverse transcription followed by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)4 because LAMP reagents are widely available and use defined buffers that are amenable to Cas enzymes. LAMP operates at 55 to 70°C and requires a thermostable Cas enzyme such as Cas12b from Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus (AapCas12b).5 We systematically evaluated multiple LAMP primer sets and AapCas12b guide RNAs (a guide RNA helps AapCas12b recognize and cut target DNA) to identify the best combination to target gene N, encoding the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, in a one-pot reaction mixture (see Figs. S1 through S3 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). We termed this assay STOPCovid, version 1 (STOPCovid.v1). As expected, STOPCovid.v1 detection produced a signal only when the target was present, whereas LAMP alone can produce a nonspecific signal (Fig. S3E). STOPCovid.v1 is compatible with lateral-flow and fluorescence readouts and can detect an internal control with the use of a fluorescence readout (Figs. S4 through S6).

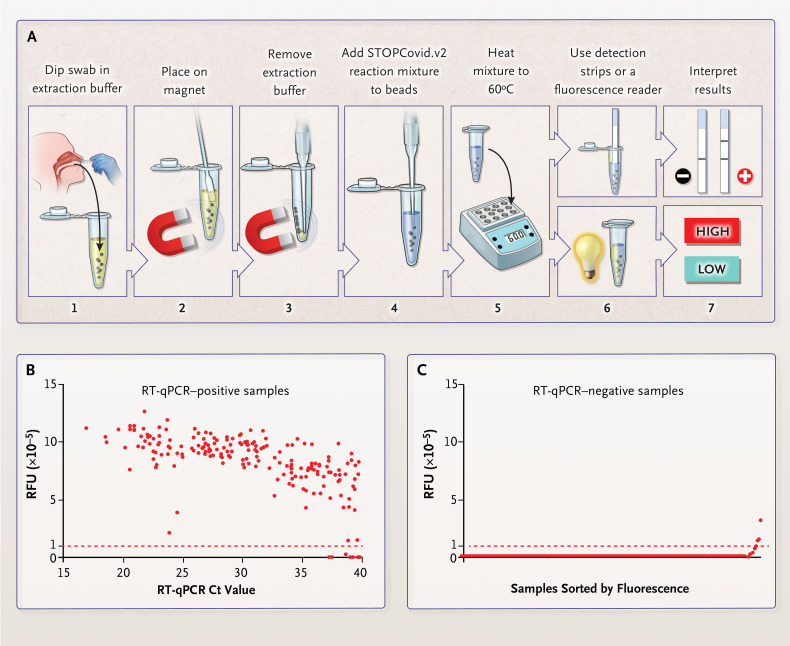

To simplify RNA extraction and to boost sensitivity, we adapted a magnetic bead purification method (Fig. S9). The magnetic beads concentrated SARS-CoV-2 RNA genomes from an entire nasopharyngeal or anterior nasal swab into one STOPCovid reaction mixture. We streamlined the test by combining the lysis and magnetic bead–binding steps and eliminating the ethanol wash and elution steps to reduce the duration of sample extraction to 15 minutes with minimal hands-on time. We refer to this streamlined test as STOPCovid, version 2 (STOPCovid.v2) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. STOPCovid, Version 2 (STOPCovid.v2) Test and Performance Evaluation.

Panel A shows a nasopharyngeal or anterior nasal swab dipped in 400 μl of extraction solution containing lysis buffer and magnetic beads (step 1). After 10 minutes at room temperature, the sample was placed on a magnet (step 2) and extraction buffer was aspirated (step 3). A total of 50 μl of STOPCovid.v2 reaction mixture was added to the beads (step 4), and the sample was heated to 60°C (step 5). For a lateral-flow readout, after 80 minutes, detection strips were dipped into the reaction mixture (steps 6 and 7, top). After 45 minutes, a fluorescence reader was used to measure the fluorescence of the reaction mixture (steps 6 and 7, bottom). Panel B shows STOPCovid.v2 results for 202 SARS-CoV-2–positive nasopharyngeal swab samples obtained from patients and detected by means of a fluorescence readout and measured in relative fluorescence units (RFUs). A swab with 50μl of viral transport medium was dipped into the extraction buffer. Cycle-threshold (Ct) values were determined with the use of standard reverse-transcription–quantitative polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-qPCR) assays. Each dot indicates one sample, and the red dashed line indicates the threshold above which samples were classified as positive. End-point fluorescence at 45 minutes is shown. Panel C shows STOPCovid.v2 results for 200 SARS-CoV-2–negative nasopharyngeal swab samples obtained from patients. The samples were sorted by means of end-point fluorescence and measured in RFUs. Each dot indicates one sample, and the red dashed line indicates the threshold for classifying samples.

We compared STOPCovid.v2 with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) standard two-step test (i.e., RNA extraction followed by RT-qPCR) (Fig. S10C). The concentration of substrate by magnetic beads in STOPCovid.v2 allowed detection of viral RNA from the entire swab sample, yielding an input (in terms of quantity of viral RNA) that was 600 times that afforded by the CDC test. As a result, STOPCovid.v2 reliably detected a viral load that was one thirtieth that detected by the CDC RT-qPCR test (100 copies per sample, or 33 copies per milliliter, as compared with 1000 copies per milliliter). Analysis of two independent dilution series from nasopharyngeal swab samples revealed that STOPCovid.v2 had a limit of detection that was similar to an RT-qPCR cycle-threshold (Ct) value of 40.3 (Fig. S10D and S10E).

In blinded testing at an external laboratory at the University of Washington, we tested 202 SARS-CoV-2–positive and 200 SARS-CoV-2–negative nasopharyngeal swab samples obtained from patients. These samples were prepared by adding 50 μl of swab specimens obtained from patients with Covid-19 to a clean swab, in accordance with the recommendation of the Food and Drug Administration for simulating whole swabs for regulatory applications (see the Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix). This testing showed that STOPCovid.v2 had a sensitivity of 93.1% and a specificity of 98.5% (Figure 1B and 1C, Fig. S11A, and Table 1). STOPCovid.v2 false negative samples had RT-qPCR Ct values greater than 37. Positive samples were detected in 15 to 45 minutes. Finally, we used fresh, dry, anterior nasal swabs (collected according to the recommendations of the CDC) to validate STOPCovid.v2, and we correctly identified 5 positive samples (Ct values, 19 to 36) and 10 negative samples (Fig. S11B through S11E). A detailed protocol for STOPCovid.v2 is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. The simplified format of STOPCovid.V2 is suited for use in low-complexity clinical laboratories.

Table 1. Positive and Negative Predictive Values, Sensitivity, and Specificity of STOPCovid.v2 for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Nasopharyngeal Samples.*.

| STOPCovid.v2 Result | Positive Samples on RT-qPCR (N=202) |

Negative Samples on RT-qPCR (N=200) |

Total Samples (N=402) |

Positive Predictive Value |

Negative Predictive Value |

Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | number/total number (percent) | ||||||

| Positive | 188 | 3 | 191 | 188/191 (98.4) | 188/202 (93.1) | ||

| Negative | 14 | 197 | 211 | 197/211 (93.4) | 197/200 (98.5) | ||

RT-qPCR denotes reverse-transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on September 16, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by a fellowship (1F31-MH117886, to Ms. Joung) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH); a fellowship (to Dr. Saito) from the Swiss National Science Foundation; a grant (to Drs. Gootenberg and Abudayyeh) from the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology; grants (to Drs. Gootenberg, Abudayyeh, and Zhang) from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation and the Massachusetts Consortium on Pathogen Readiness Evergrande Covid-19 Response Fund; and grants (to Dr. Zhang) from the NIH (1R01-MH110049 and 1DP1-HL141201), the Mathers Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Open Philanthropy Project, and James and Patricia Poitras and Robert Metcalfe.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org

References

- 1.Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Lee JW, et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 2017;356:438-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JS, Ma E, Harrington LB, et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 2018;360:436-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broughton JP, Deng X, Yu G, et al. CRISPR-Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Biotechnol 2020;38:870-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2000;28(12):E63-E63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teng F, Cui T, Feng G, et al. Repurposing CRISPR-Cas12b for mammalian genome engineering. Cell Discov 2018;4:63-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.