Abstract

Background

Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) have a high prevalence of mood disorders. Lamotrigine (LAM) is often used as an off-label therapeutic option for BPD. We aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy and tolerability of LAM for the treatment of BPD.

Methods

We comprehensively searched electronic databases for eligible studies from the inception of databases to September 2019. Outcomes investigated were BPD dimensions, tolerability, and adverse events. Quality assessments were completed for the included studies. Data were summarized using random-effects model.

Results

Of the 619 records, five studies, including three randomized controlled trials (RCT; N = 330) were included for the qualitative analysis. A meta-analysis conducted on two RCTs measuring LAM efficacy at 12 weeks, showed no statistically significant difference at 12 weeks (SMD: −0.04; 95% CI: −0.49, 0.41; p = 0.87; I2 = 38%) and at study endpoints (SMD: 0.18, 95%CI: −0.89, 1.26; p = 0.74; I2 = 86%) as compared to placebo. Sensitivity analysis on three RCTs measuring impulsivity/aggression showed no statistically significant difference between LAM and placebo (SMD: −1.84, 95% CI: −3.94, 0.23; p = 0.08; I2 = 95%). LAM was well tolerated, and quality assessment of the included trials was good.

Conclusions

Our results suggest there is limited data regarding efficacy of lamotrigine in BPD. There was no consistent evidence of lamotrigine’s efficacy for the core symptom domains of BPD. Future studies should focus on examining targeted domains of BPD to clarify sub-phenotypes and individualized treatment for patients with BPD.

Keywords: lamotrigine, borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, ZAN-BPD, depression, affective lability, efficacy

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder is defined by a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationship, self-image, affect and marked impulsivity generally beginning in early adulthood and is present in multiple contexts.1 BPD is the fourth most prevalent2,3 personality disorder of all the ten DSM-IV personality disorders. According to the literature, the 2–5 years prevalence of BPD in the general population is estimated to be between 0%–4.5%, with a median of 1.7% in large epidemiological studies.4 In a National Epidemiological survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) from the United States, lifetime prevalence of BPD was approximate 5.9% for BPD with no differences by gender.5 Even though the community prevalence of BPD is comparable to other personality disorders, it is highly prevalent in clinical psychiatric populations: 10–28% in psychiatry outpatient,6–9 18%–43% in psychiatry inpatients,10–13 around 6% in primary care settings14 and 10%–15% in emergency rooms.15,16

The symptoms of BPD can be divided into four domains: cognitive, interpersonal, affective, and impulsivity.1 However, persistent controversies about its definition, core symptom pathology and effective treatment options remain, often leading to misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment of care. Like other psychiatric disorders, BPD has a genetic and biological basis. Twin studies have suggested the mean heritability around 40%,17 which varies in different studies from 35%18 to 69%.19 The treatment of BPD is multifactorial with long-term psychotherapy and focused pharmacotherapy.20 Pharmacotherapy is usually used to treat three behavioral dimensions—impulsivity, affective dysregulation and cognitive-perceptual difficulties, even though there is no FDA approved drug for BPD. Mood stabilizers have increasingly been used for treatment as it has been proposed that there is a common pathogenetic mechanism underlying both BPD affective instability and bipolar disorder (BD) rapid mood cycling.21,22

Lamotrigine (LAM), an inhibitor of voltage-sensitive sodium channels, is FDA approved as a maintenance therapy for BD. LAM is reasonably well-tolerated, albeit with the risk of severe rash—Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (incidence = 0.04%).23 The risk of severe rash is generally limited to the initiation period, rapid dose escalation, or with irregular intake.24 Clinical trials assessing the efficacy of LAM in patients with BPD25–27 have shown mixed results in the symptomatic treatment of BPD.

We aimed to conduct this comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to pool and analyze the available data on the efficacy of LAM in BPD, and study its efficacy in different domains of BPD. Additionally, we also aimed to study efficacy of LAM in BPD and BD comorbidity.

Methods

Our systematic review and meta-analysis is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines.28 A protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020155946).

Data Sources and Search

A comprehensive search through the OVID interface was conducted for Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. We also searched for the databases of ongoing clinical trials (e.g. http://www.controlled-trials.com/ or http://clinicaltrials.gov/) through September 2019. The search strategy was conducted by an expert librarian using a controlled vocabulary and key words (“borderline personality”, “bipolar disorder”, “lamotrigine”, “response”, “remission”, “depression Scores”, “ZAN-BPD” (Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder), “affective lability”, “Mc Lean screening”) to identify the potential eligible studies. Search was performed in all the languages and was limited to human subjects and controlled clinical trials. The complete search strategy is available in the “Supplement–Table S1”. To minimize publication bias, references cited in potentially eligible articles were hand-searched.

Study Selection

Two reviewers (BS and MP) independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible articles. Subsequently, the full texts of eligible articles were reviewed separately by the same two reviewers. For meta-analysis, we selected all the randomized controlled trials (RCTs), comparing LAM with control/placebo in patients with BPD with or without BD. For systematic review, we included RCTs, case-control/cohort (retrospective/prospective)/cross-sectional studies, case series with > 10 patients from inception of database till latest. Any disagreement between the reviewers was resolved by consensus. The inter-reviewer agreement for study selection was measured with Cohen’s weighted k.

Quality of Bias Assessment

The methodological quality of the RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane collaboration’s Risk Interventions Risk of Bias Tool examining selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other biases. Each criterion was reported as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias.29 Quantitative tests to assess publication bias were not performed due to the limited number of studies.30

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviations (SD) or standard errors (SE). We computed the standardized mean difference (SMD) for the variable analyzed reporting the effect sizes with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Der-Simonian and Laird random effects model.31 Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using the I2 statistic.32 The I2 statistic measures the percentage of variability that cannot be attributed to random error. All the statistical analyses were conducted using the “meta” (version 4.9.6) and “metafor” (version 2.1.0) packages of R software for statistical computing (version 3.6.1) in R Studio (version 1.2.1335).33–36 An alpha level of 0.05 was chosen for statistical significance.

Results

The search identified a total of 621 potentially relevant studies (Figure 1). A total of 5 studies (N = 378) met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review (Table 1), comprising 3 RCTs25–27 (N = 170, LAM, N = 160, placebo), and one case series studying the efficacy of LAM among patients with BPD (N = 13),37 and one retrospective study (N = 35) including patients with BPD and BD.38 The interreviewer agreement (k) for study selection was 0.87 (percent agreement =99%). Participants were adults with a mean age from 28 to 36 years and were diagnosed with BPD. Females constituted more than 75% of the population. LAM dosing strategy varied between studies with doses initiated between 25–50 mg and titrated up to achieve maximum dose of 200 mg in 6 to 8 weeks. Follow-up duration also varied among the studies ranging from 12 to 72 weeks.27,37–39 Two studies included patients with adjunctive psychotropic medications; antidepressants in Reich et al.26 and adjunctive lithium and/or antidepressants in BD subgroup in Preston et al.38 Details of the studies included in the systematic review are described in Table-1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the Procedure for Study Selection

Table 1. Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Review.

| Author | Intervention(N) | Dosage regimen Or Mean dose(MG) |

Study Duration | Type of Study | Total Patients, Females [N (%)] |

Mean Age (SD) | Primary Outcome Measure | Baseline outcome, Mean (SD) | Endpoint outcome, Mean (SD) | Conclusions |

| Crawford et al. 2018 |

Lamotrigine (137) v placebo (139) |

2wk:25–50 4wk:100 6wk:200 If on OCP: 8wk:300 10wk:400 |

52 wk. | RCT | 276 208(75.4) |

L = 36.0(11) P = 36.2(11) |

ZAN-BPD | LAM = 16.6(5.8) P = 17.4(6.2) |

LAM = 11.3(6.6) P = 11.5(7.7) |

Negative: Adding LAM to treatment as usual was not significantly different then placebo. |

| Reich et al. 2009 |

Lamotrigine (15) v placebo (13) |

Mean dose: 93.3 | 12 wk. | RCT | 27, 24(88.9) |

L = 28.4(9.5) P = 34.8(9.7) |

ZAN-BPD | LAM = 17.7(7.5) P = 20.2(2.4) |

L = 8.9(5.0) P = 13.6(5.4) |

Positive: LAM is effective for the affective instability domain. Negative: No difference in change of ZAN-BPD Scores in two groups. |

| Weinstein et al. 2006 |

Lamotrigine (13) | Mean dose: 130.8 | 12–60 wk. | Case review | 13,13 (100) | L = 30.6 | CGI | LAM = 6 or 5 (n/a) | LAM = 2 or 1 (n/a) | Positive: LAM effective for the affective instability associated with BPD. |

| Tritt et al. 2005 |

Lamotrigine (18) v placebo (9) |

2wk:50 3wk:100 4–5wk:150 6–8wk:200 |

8 wk. | RCT | 27,27 (100) | L = 29.4 P = 28.9 |

STAXI | LAM = 25.3(3.5) P = 24.8(3.1) |

LAM = 17.8(3.0) P = 23.2(3.7) |

Positive: LAM effective for anger out and anger control in BPD. |

| Preston et al. 2002 |

Lamotrigine (35) | n/a | 8 wk. | Retrospective 35 | BD = 34.9 BD+BPD = 40.9 |

CGI | BDonly = 4.4(0.5) BD+BPD = 4.6(0.5) |

n/a |

Positive: LAM effective for affective/non-affective symptoms in comorbid BPD+BD. Negative: Adjunctive Use of lithium and /or antidepressants. |

BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder; BD: Bipolar Disorder; RCT: randomized controlled trial; CGI: Clinical Global improvement scale; ZAN-BPD: Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder; STAXI: State Trait Anger Expression Inventory; LAM: Lamotrigine; P: Placebo; wk.: weeks; N/A: not available ;OCP: Oral Contraceptive Pill.

Quality Assessment

The assessment of methodological quality of the RCTs included in the meta-analysis was done using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool (Supplemental appendix. Table-S2 and Figure S1). Overall included studies in the meta–analysis showed a low risk of bias with an unclear risk of bias for the selective reporting criteria.

Effects on ZAN-BPD

Two RCTs26,27 used ZAN-BPD to examine the clinical effectiveness of LAM in patients with BPD. On pooled analysis, LAM was not statistically significant as compared to placebo in reducing BPD symptoms measured using ZAN-BPD scores at 12 weeks (SMD =−0.04, 95%CI −0.49, 0.41; p = 0.87) (Figure 2) as well as at endpoint (SMD = −0.18, 95%CI -0.89, 1.26; p = 0.74) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of Pooled ZAN-BPD Standardized Mean Differences for Efficacy of Lamotrigine at 12 Weeks

Figure 3.

Forest Plot of Pooled ZAN-BPD Standardized Mean Differences for Efficacy of Lamotrigine at Endpoint

Effects on Affective Dysregulation

Reich et al.26 studied the affective lability by using affective lability scale (ALS) in BPD and found that the LAM group had significantly greater reductions in mean total ALS score of almost twice as large (1.8 times) than the placebo group. Crawford et al.27 reported a mean reduction of 2.2 in the subgroup of affective disturbance component with LAM; however this change was not significant as compared to placebo. Weinstein and Jamison37 studied affective instability in BPD patients and found improvement in 85% of patients with LAM as measured by CGI scores.

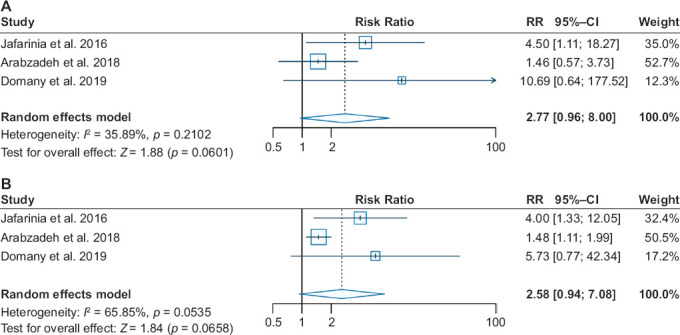

Effects on Impulsivity/Aggression

Reich et al.26 reported mean baseline ZAN-BPD scores for general impulsivity in the range of ‘moderate symptoms’ for each group (corresponding to a score of 2 on ZAN-BPD).There was a significant difference in the mean change general impulsivity scores from baseline to the end of 12 weeks, between the two groups. The LAM group had an average decrease of 1 point change in their impulsivity scores from ‘moderate’ to ‘mild’.26 Crawford et al.27 reported a mean decline of 0.9 in the mean scores of impulsivity but there was no significant difference as compared to the placebo. A secondary analysis of three RCTs25–27 measuring the impulsivity/aggression domain showed no significant difference between LAM and placebo and a high heterogeneity (SMD: −1.84, 95%CI, -3.92; 0.23, p = 0.08, I2 = 95%) (Figure 4). Even on a sensitivity analysis (after excluding study by Tritt et al.) to assess the efficacy of LAM for impulsivity only, there was no significant difference between LAM and placebo (p = 0.37).26,27

Figure 4.

Forest Plot of Pooled Impulsivity/Aggression Standardized Mean Differences for Efficacy of Lamotrigine

Tritt et al.25 studied aggression using State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) scale and found the Anger-Out and Anger-Control scales for LAM was associated with a gradual change in the first four weeks, but later a relatively rapid change was noticed in the self-reported Anger-Out and in Anger-Control (p < 0.01). There were moderate but significant changes noted on the AI (Anger-In) scale too, with 2.1 point reduction in scores from initial evaluation between LAM and placebo (p < 0.05). Leiberich et al.39 followed the patients (from the study by Tritt et al.) up to 18 months and reported there was a significantly greater change on all STAXI scales in the LAM-treated group as compared to the placebo group. Specifically, LAM was more effective in treating the aggression component of borderline psychopathology, which aligned with their previous report.25 In a retrospective study design, Preston et al.38 reported a 48% improvement in the cohort burden (number of patients who initially experienced the symptom) for the impulsivity dimension of BPD; in the comorbid BPD-BD group, 63% of the cohort had response in impulsivity dimension with LAM.

Self-Harm

Crawford et al.27 reported a decline in deliberate self-harm (DSH) behaviors with LAM; 70% of patients with DSH at baseline reduced to 46% at the end of 52 weeks, and in the control group it decreased from 63% to 39%. Preston et al. reported a 63% response in self-harm dimension in the BPD-BD group compared to a 50% response in the BD group.

Adverse Events

Of the five included studies, only two RCTs provided detailed information regarding adverse events.26,27 Adverse-events were similar between LAM and the placebo group except for infectious disorders (OR 0.53, 95% CI, 0.30- 0.94; p = 0.03) which were less prevalent in the LAM group. A detailed description of adverse events is included in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the Adverse Events By System Across the Included Studies For The Meta-Analysis.

| Adverse events | LAM | Placebo | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

| Immune and blood disorders | 3 | 4 | 0.74 (0.16, 3.36), p = 0.70 |

| Cardiac disorders | 0 | 1 | 0.33 (0.13, 8.14), p = 0.48 |

| Eye disorders | 1 | 6 | 0.16 (0.02, 1.35), p = 0.06 |

| Metabolic disorders | 3 | 2 | 1.39 (0.22, 8.44), p = 0.71 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 38 | 55 | 0.64 (0.39, 1.03), p = 0.06 |

| Infection disorders | 23 | 38 | 0.53 (0.30, 0.94), p = 0.03 |

| Urinary and reproductive disorders | 4 | 1 | 4.05 (0.45, 36.7), p = 0.18 |

| Respiratory disorders | 16 | 9 | 1.86 (0.80, 4.34), p = 0.15 |

| Skin and musculoskeletal disorders | 46 | 38 | 1.29 (0.78, 2.14), p = 0.32 |

LAM – Lamotrigine.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes the available evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of LAM for the treatment of BPD. Our results, based on three RCTs25–27 suggest that LAM is not superior to placebo for the treatment of patients with BPD. Overall LAM was well tolerated, patients reported mild side-effects which were similar to placebo. In pooled analysis, evaluating the efficacy of LAM for core symptoms of impulsivity, LAM was not superior to placebo. Although two previous RCTs showed improvement in aggression/impulsivity with LAM among patients with BPD, the latest RCT27 which comprised of a larger sample size, was not significant when compared to placebo. Only one RCT26 and one retrospective study38 showed LAM may have an effect on aggression in BPD.

Despite recent advances in the field, there is still no FDA approved medication for BPD. Several studies have suggested a role of mood stabilizers targeting the affective instability and impulsivity domains.40–42 However, LAM is commonly utilized by clinicians as an off-label option to target impulsivity and affective instability. LAM was first suggested as a treatment option more than 20 years ago in a case series of BPD patients in which more than 80% of the patients required a mood stabilizer and 50% of them achieved a remission state with LAM.43 An earlier review of pharmacological treatment for BPD41 suggests some beneficial effects with mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics for treating core symptoms of BPD. However, we did not see a significant difference between LAM and placebo for treating core symptoms of impulsivity. We were not able to pool data for affective instability domain due to different scales. These finding needs to be further explored in future studies.

Considering the chronic nature of BPD and its treatment, it is important to weigh the side-effect profile of the drugs as they tend to be prescribed for longer periods of time and there is a relative increased rate of early attrition from treatment due to side-effects in patients with BPD.40 For example, a retrospective chart review in 165 patients examined psychotropic medication use in hospitalized BPD patients (n = 85) compared to major depressive disorder, underscoring a higher prescription of medications in patients with BPD, thus, leading to poly-pharmacy and increased risk of side-effects.44

Some plausible explanations for the inconclusive findings in our review can be explained by methodological aspects of clinical trial design such as variability of sample size and comorbid psychiatric characteristics. Crawford et al.27 conducted an expedient trial by including a broad range of patients with a minimal exclusion criteria including inpatient referrals, history of DSH, low-employment status, whereas other two trials25,26 recruited patients through advertisement and had a less severe psychopathology. Crawford et al.27 followed the patients for 12 months as compared to 12 weeks or less in the two trials.25,26 In addition, in the study by Crawford et al.27 up to 40% of the participants had an alcohol disorder or drug misuse at study entry and approximately 31% of participants had stopped LAM by 12 weeks, and 60% of participants had stopped LAM by 52 weeks. The low medication adherence rate may have reduced the magnitude of any treatment effect that might be observed in participants randomized to receive either placebo or LAM.

Secondly, a placebo effect in treatment response has been described in BPD.45 The placebo effect has been extensively studied and underscored in a meta-analysis which evaluated the efficacy of pharmacological agents (anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, antidepressants) for BPD in the following domains: affective dysregulation (moderate effect size), impulsivity, and cognition (all studies with small effect sizes).46 The presence of a placebo effect has not only been described for pharmacological treatments but for other treatment modalities like psychotherapies contributing to the high significant remission rates in patients with BPD.46,47 The possibility of a high placebo effect in the placebo group leading to inappreciable differences when compared to LAM is a possible explanation.

Third, a plausible explanation for the reduced efficacy of LAM in our analysis could be related to variable dosing of LAM. Interestingly, none of the included studies used dosing of LAM beyond 200–225 mg, whereas therapeutic daily dose range of LAM between 200–400 mg has shown to be effective in patients with BD.48

Fourth, all the trials excluded patients with major Axis I diagnosis. Comorbid Axis I disorders are very frequent in BPD, mainly mood disorders (96.9%) and substance use disorders (62.1%).49 Excluding such cases makes it difficult to generalize the results of the RCT to the population seen in clinical practice. Also, BD and BPD has shown to co-occur in 15% of patients.47 However, we could not identify any RCTs evaluating the efficacy of LAM for patients with BD and BPD. We identified only one retrospective study38 with BD and comorbid BPD which could not be included in the meta-analysis due to the study design and different patient populations. Consequently, LAM may have an increased benefit for patients with comorbid BPD and BD.

There are several limitations of our systematic review and meta-analysis that should be acknowledged. A major limitation is the small number of included studies and high heterogeneity detected among the studies. Heterogeneity could be due to the difference in drug formulation, dosing, duration of treatment, different study populations, and follow-up. Additionally, methodological aspects clinical trial designs in the studies may account for the variability and the inconsistence in the results.

This systematic review and meta-analysis has several strengths that include a comprehensive literature search for all major databases, a manual search of all references in the included studies to avoid selection bias, and searches of recent conference proceedings to minimize the impact of publication bias. To address the clinical heterogeneity across studies, we decided to use a-priori random effects model for the meta-analysis. There were only two RCTs26,27 measuring the overall effect of LAM on BPD characteristics by ZAN-BPD scales and three measuring impulsivity/aggression.25–27

In conclusion, there is limited data regarding the efficacy of LAM in BPD. Our results suggest that currently, LAM has no consistent evidence for efficacy in core domains of BPD. However, there may be a marginal effect on aggression in BPD which needs to be further explored. Furthermore, the neurobiological intersection between BD and BPD remains as a plausible distinct sub-endophenotype. Future studies should focus on examining targeted domains of BPD to clarify sub-phenotypes and individualized treatment for patients with BPD.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Ms. Lori L. Solmonson and Ms. Angie Lam for their critical review and editing in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Singh received research time support from Medibio. It is unrelated to the current study. Dr. Singh reports grant support from Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Frye reports grant support from Assurex Health, Mayo Foundation, Medibio. Consultant (Mayo)—Actify Neurotherapies, Allergan, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc., Janssen, Myriad, Neuralstem Inc., Takeda, Teva Pharmaceuticals. He reports CME/Travel/Honoraria from the American Physician Institute, CME Outfitters, Global Academy for Medical Education.

Other authors have none to declare.

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplements

Table S1. Search Strategy.

| # | Searches | Results | Type |

| EBM Reviews | |||

| 1 | (lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium).ab,kw,ti. | 1336 | Advanced |

| 2 | borderline.ab,hw,ti. | 4509 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 18 | Advanced |

| 4 | Remove duplicates from 3 | 17 | Advanced |

| Embase | |||

| 1 | exp lamotrigine/ | 24209 | Advanced |

| 2 | (lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium).ab,kw,ti. | 8404 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 and 2 | 24688 | Advanced |

| 4 | exp borderline state/ | 12940 | Advanced |

| 5 | borderline.ab,kw,ti. | 60454 | Advanced |

| 6 | 4 OR 5 | 634832 | Advanced |

| 7 | 3 AND 6 | 271 | Advanced |

| 8 | exp child/ NOT exp adult/ | 1847748 | Advanced |

| 9 | 7 NOT 8 | 256 | Advanced |

| # | exp case report/ OR “case report”.kw,pt.ti. | 2441197 | Advanced |

| # | 9 NOT 10 | 222 | Advanced |

| Medline | |||

| 1 | exp Lamotrigine/ | 3007 | Advanced |

| 2 | (lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium).ab,kf,ti. | 5138 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 OR 2 | 5522 | Advanced |

| 4 | exp Borderline Personality Disorder | 6630 | Advanced |

| 5 | borderline.ab,kf,ti. | 41116 | Advanced |

| 6 | 4 OR 5 | 42108 | Advanced |

| 7 | 3 AND 6 | 43 | Advanced |

| 8 | exp CHILD/ NOT exp ADULT/ | 1184030 | Advanced |

| 9 | 7 NOT 8 | 42 | Advanced |

| # | exp Case Reports/ OR “case report”.kf,pt.ti. | 2106899 | Advanced |

| # | 9 NOT 10 | 35 | Advanced |

| PsycINFO | |||

| 1 | (lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium).ab,id,ti. | 2001 | Advanced |

| 2 | exp borderline personality disorder/ OR exp borderline states/ | 10406 | Advanced |

| 3 | Borderline.ab,id,ti. | 20008 | Advanced |

| 4 | 2 OR 3 | 20179 | Advanced |

| 5 | 1 AND 4 | 34 | Advanced |

| 6 | exp Case Report/ OR “case report*”.id,pt,ti. | 30493 | Advanced |

| 7 | 5 NOT 6 | 34 | Advanced |

| Scopus | |||

| 1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY(lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium) | 22568 | Advanced |

| 2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY(borderline) | 60662 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 AND 2 | 258 | Advanced |

| Web of Science | |||

| 1 | Topic: (lamotrigine OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine” OR “3,5-diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-as-triazine” OR “6-(2,3 dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine-3,5-diamine” OR “bw-430c*” OR bw430c* OR crisomet OR labileno OR lamepil OR lamictal OR lamiktal OR lamictin OR lamodex OR lamogine OR lamotrix OR lamotrigine OR neurium) | 7606 | Advanced |

| 2 | Topic: borderline | 38006 | Advanced |

| 3 | 1 AND 2 | 63 | Advanced |

Table S2. Risk of bias for RCTs Included in Meta-Analysis.

| Criteria | Crawford et al. 2018 | Tritt et al. 2015 | Reich et al. 2009 |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed (attrition bias) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk |

Figure S1.

Risk of bias for RCTs Included in Meta-Analysis

References

- 1.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) 2013 doi: 10.1590/s2317-17822013000200017. APA. American Psychiatric Pub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torgersen S. American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Personality Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol AE, Oldham JM. Cumulative prevalence of personality disorders between adolescence and adulthood. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(5):410–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunderson JG, Herpertz SC, Skodol AE, Torgersen S, Zanarini MC. Borderline personality disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18029. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, Rosenstein L. Principal diagnoses in psychiatric outpatients with borderline personality disorder: Implications for screening recommendations. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(1):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chanen AM, Jovev M, Djaja D et al. Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(4):353–364. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. The frequency of personality disorders in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(3):405–420, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korzekwa MI, Dell PF, Links PS, Thabane L, Webb SP. Estimating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in psychiatric outpatients using a two-phase procedure. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M et al. Patterns of covariation of DSM-IV personality disorders in a mixed psychiatric sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41(3):206–215. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90049-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marinangeli MG, Butti G, Scinto A et al. Patterns of comorbidity among DSM-III-R personality disorders. Psychopathology. 2000;33(2):69–74. doi: 10.1159/000029123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Quinlan DM, Walker ML, Greenfeld D, Edell WS. Frequency of personality disorders in two age cohorts of psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(1):140–142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paruk L, Janse van Rensburg ABR. Inpatient management of borderline personality disorder at Helen Joseph Hospital, Johannesburg. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2016;22(1):678. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v22i1.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff M et al. Borderline personality disorder in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(1):53–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaput YJ, Lebel MJ. Demographic and clinical profiles of patients who make multiple visits to psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):335–341. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomko RL, Trull TJ, Wood PK, Sher KJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder in a community sample: comorbidity, treatment utilization, and general functioning. J Pers Disord. 2014;28(5):734–750. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amad A, Ramoz N, Thomas P, Jardri R, Gorwood P. Genetics of borderline personality disorder: systematic review and proposal of an integrative model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;40:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Roysamb E et al. Major depression and dimensional representations of DSM-IV personality disorders: a population-based twin study. Psychol Med. 2010;40(9):1475–1484. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torgersen S, Lygren S, Oien PA et al. A twin study of personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2000;41(6):416–425. doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.16560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10 Suppl):1–52. American Psychiatric Association Practice G. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiskal HS. Demystifying borderline personality: critique of the concept and unorthodox reflections on its natural kinship with the bipolar spectrum. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(6):401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173–1178. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloom R, Amber KT. Identifying the incidence of rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in patients taking lamotrigine: a systematic review of 122 randomized controlled trials. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(1):139–141. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowden CL, Singh V. Lamotrigine (Lamictal IR) for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(17):2565–2571. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.741590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tritt K, Nickel C, Lahmann C et al. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline-patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2005;19(3):287–291. doi: 10.1177/0269881105051540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reich DB, Zanarini MC, Bieri KA. A preliminary study of lamotrigine in the treatment of affective instability in borderline personality disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;24(5):270–275. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832d6c2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B et al. Lamotrigine for people with borderline personality disorder: a RCT. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2018;22(17):1–68. doi: 10.3310/hta22170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2011 Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2000;53(11):1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwarzer G. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7(3):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36(3):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2019. [computer program]. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio Team, RStudio Inc.; Boston, MA: 2016. [computer program]. http://www.rstudio.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinstein W, Jamison KL. Retrospective case review of lamotrigine use for affective instability of borderline personality disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2007;12(3):207–210. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preston GA, Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Strong RE, Hedges DW. Borderline personality disorder in patients with bipolar disorder and response to lamotrigine. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;79(1–3):297–303. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leiberich P, Nickel MK, Tritt K, Gil FP. Lamotrigine treatment of aggression in female borderline patients, Part II: An 18-month follow-up. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22(7):805–808. doi: 10.1177/0269881107084004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borderline personality disorder: Treatment and management. NICE Clinical Guideline. 2009:78. NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieb K, Vollm B, Rucker G, Timmer A, Stoffers JM. Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(1):4–12. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stone MH. Borderline Personality Disorder: Clinical Guidelines for Treatment. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2019;47(1):5–26. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2019.47.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinto OC, Akiskal HS. Lamotrigine as a promising approach to borderline personality: an open case series without concurrent DSM-IV major mood disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1998;51(3):333–343. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moeller KE, Din A, Wolfe M, Holmes G. Psychotropic medication use in hospitalized patients with borderline personality disorder. Mental Health Clinician. 2016;6(2):68–74. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.03.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone MH. Borderline Personality Disorder: Therapeutic Factors. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2016;44(4):505–539. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2016.44.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vita A, De Peri L, Sacchetti E. Antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and placebo on the symptom dimensions of borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled and open-label trials. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;31(5):613–624. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31822c1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gunderson JG, Choi-Kain LW. Medication Management for Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):709–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18050576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng F, Hallam K, Lucas N, Berk M. The role of lamotrigine in the management of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):463–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2108–2114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]