Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether approved gastroprokinetic agent, acotiamide exerts a direct excitatory effect in bladder to help explain the reported meaningful reduction of post-void residual urine volume (PVR) in detrusor underactivity (DU) patients after thrice daily oral intake of acotiamide 100 mg for 2 weeks.

Methods

Effect of acotiamide [1–16μM] was assessed on nerve-mediated contractions evoked by electrical field stimulation (EFS) for 5s with 5ms pulse trains of 10V in longitudinal, mucosa intact rat and human bladder strips to construct frequency response curve (1–32Hz) and repeat 10Hz stimulation at 60s interval. Effect of acotiamide 2μM on spontaneous and carbachol evoked contractions was also assessed.

Results

Acotiamide 2μM significantly enhanced the Atropine and Tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive EFS evoked contractions of rat and human bladder at 8–32Hz (Two-way ANOVA followed Sidak’s multiple comparison; *p<0.01) and on repeat 10Hz stimulation (Paired Student’s t test;*p<0.05), while producing a modest effect on the spontaneous contractions and a negligible effect on the carbachol evoked contractions.

Conclusions

Enhancement of TTX-sensitive evoked contractions of rat and human bladder by acotiamide is consistent with the enhancement of excitatory neuro-effector transmission mainly through prejunctional mechanisms. Findings highlights immense therapeutic potential of antimuscarinics with low M3 receptor affinity like acotiamide in Underactive bladder (UAB)/DU treatment.

Keywords: Underactive bladder, Acotiamide, Antimuscarinic, nerve evoked, Bethanechol

Introduction-

Underactive bladder (UAB) is characterized by hesitancy, prolonged urination with or without a sensation (Smith et al., 2015) of filling or incomplete bladder emptying, a slow stream and large post-void residual (PVR). Often, UAB is associated detrusor underactivity (DU) - a urodynamic analog of detrusor overactivity (DO)- defined by the International continence society as a detrusor contraction of inadequate strength and/or duration resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or a failure to achieve complete bladder emptying, in the absence of urethral obstruction. Although, currently available drugs (α1-blockers) are effective in managing obstructive urinary retention (urinary hesitancy and prolonged urination) (Oelke et al., 2013), their efficacy in the treatment of non-obstructive urinary retention is poor. Poor efficacy prompts the search for newer drugs and motivate the efforts to repurpose already approved drugs.

Appearance of an analogous relationship between DU and DO prompted some experts to argue that UAB is an antithesis of overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms. A strong association of DO with lower acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in bladder of rodents (Kashyap et al., 2016) and patients (Mills et al., 2000) supports the argument that the rate of AChE mediated ACh degradation (Yossepowitch et al., 2001) determines the functionally active acetylcholine (ACh) levels available at the neuromuscular junction (Braverman et al., 1998, D’Agostino et al., 1989, Smith et al., 2003, Zagorodnyuk et al., 2009), which ultimately determines the strength and duration of detrusor contraction(Izumi et al., 2014). Furthermore, successful management of responsive and treatment refractory OAB symptoms through competitive blockade of ACh action (antimuscarinics) as well as with the inhibition of ACh release by onabotulinumtoxin A, respectively (Tyagi et al., 2017) supports the association of enhanced ACh activity with the etiology of OAB symptoms.

In contrast to OAB, deficiency in cholinergic neurotransmission (Yoshida et al., 2004) is a plausible factor in the diminished sensation of bladder filling (Smith et al., 2015) and a weaker detrusor contraction of UAB patients. Indeed, impaired voiding function of aged rodents is demonstrably linked to their cholinergic deficiency (Zhao et al., 2010). An apparent analogous etiologic relationship between OAB and UAB may have motivated the inversion of a successful OAB pharmacological approach to accomplish an excitatory effect in patients afflicted with nonobstructive urinary retention and OAB. Thus, the development of a synthetic cholinomimetic (bethanechol) or AChE inhibitor (distigmine) (Izumi et al., 2014) for an excitatory effect in bladder appears analogous to the development of antimuscarinics for OAB. However, the search for an UAB treatment approach analogous to the mechanism of action of onabotulinumtoxin A in OAB (Tyagi et al., 2017) is still ongoing. An indirectly acting cholinergic agonist that seeks to augment the activity of endogenously released ACh instead of directly stimulating the post-junctional muscarinic receptors would fit that bill.

An indirect cholinergic approach tried so far in UAB is the competitive inhibition of AChE by distigmine, which was able to reduce PVR significantly enough to obviate the need for intermittent self-catheterization (Izumi et al., 2014). Most importantly, distigmine treatment discontinuation associated increase in the PVR of UAB patients suggests a mechanistic link between increased PVR and the increased AChE activity (Izumi et al., 2014). Another approach that is mechanistically akin to distigmine is to augment the ACh activity by targeting the autoregulation of nerve evoked ACh release for stronger voiding contraction(Kim, 2017). It is known that pre-junctional M1 auto-receptors exert a positive auto-feedback on evoked ACh release(Somogyi et al., 1994) but pre-junctional M2, M3 and M4 auto-receptors exert a negative feedback on the evoked ACh release (D’Agostino et al., 2000) at the neuromuscular junction. Detrusor contraction for voiding can be driven by sole stimulation of post-junctional M3 receptors is demonstrated by carbachol evoked contraction of human bladder(Fetscher et al., 2002). Since prejunctional muscarinic autoreceptors exert an inhibitory action on cholinergic neuro-effector transmission, we surmise that muscarinic antagonist lacking functional antagonism of M3 receptors can potentially enhance voiding function. Indeed, Acotiamide, a non-selective muscarinic antagonist having an amide bond (Fig.1) in its pharmacophore instead of an ester bond of acetylcholine and the carbamate bond of Bethanechol or cholinesterase inhibitors failed to functionally antagonize recombinant M3 receptors expressed on oocytes in concentrations upto 100 μM (Doi et al., 2004). Furthermore, daily oral treatment of acotiamide (approved gastroprokinetic agent in Asian countries) led to a significant reduction of PVR in DU patients (Sugimoto et al., 2019, Sugimoto et al., 2017, Sugimoto et al., 2015) without the blockade of post-junctional M3 receptor signaling. Following study seeks to answer the question, whether acotiamide (Z-338)(Tyagi et al., 2019) has a direct excitatory action on nerve-mediated bladder contractions via pharmacological antagonism of prejunctional muscarinic receptors.

Fig 1:

Chemical structure - Acotiamide has an amide bond in pharmacophore instead of the ester bond of acetylcholine and the carbamate bond of Bethanechol and cholinesterase inhibitors.

Material and Methods-

Drugs-

Acotiamide dihydrochloride (Cat no. SML 1569) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and aqueous, stock solution was prepared and kept at −20°C until the day of experiment. Carbachol (Cat no. C4382) and Bethanechol (Cat no. C5259) for control experiments were also procured from Sigma-Aldrich.

Isolated Rat Bladder -

Adult male disease- free Sprague-Dawley rats (10–12 weeks old) were obtained from Envigo. Whole bladder removed from ten rats was euthanized by carbon dioxide overdose as per American Veterinary Medical Association. Removed bladders were dissected in pre-oxygenated cold Kreb’s physiological solution into four to five longitudinal, mucosa intact strips (~4 × 10 mm) (Kashyap et al., 2016, Kashyap et al., 2018), mounted vertically between platinum ring electrodes in organ bath chambers containing 20mL Kreb’s physiological solution composed of 118mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4 1.2mM, CaCl2, 2.5 mM, 1.2 mM KH2PO4 and 11.5 mM glucose, warmed to 37°C and constantly bubbled with 95% oxygen-5% carbon dioxide. Strips were stretched slowly to achieve a final isometric tension of 10mN and then washed three times with fresh solution every 20 min during an equilibration period of 60 min. Isometric tension generated by strips was measured using force transducers connected to a bridge amplifier (World Precision Instruments) and digitized by PowerLab Software. Electrical field stimulation (EFS) for 5s was delivered via pulse trains of 10 volts (V) in amplitude with pulse duration of 5ms at ascending frequency of 1, 2, 4,8, 16 and 32Hz (one stimulation at each frequency) at 60 s intervals. Pulses were delivered using bipolar platinum electrodes placed approximately 1 cm apart of tissue strip from constant-current Grass S88 stimulator. Frequency-response curves with the above stated EFS parameters were constructed on equilibrated strips at baseline and 30 minutes after the addition of acotiamide 1–16μM in the bath. Separate strips were used for evaluating the effect of acotiamide at different concentrations on EFS. EFS evoked contractions sensitive to 1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX), a neuronal Na+ channel blocker and atropine 5 μM were considered nerve evoked (neurogenic) (Kashyap et al., 2018). Considering that atropine sensitive (ACh mediated) EFS contractile response are dominant at EFS frequencies ≥ 10Hz (Braverman et al., 1998, Kashyap et al., 2018), we also assessed the contractile responses to repeat 10Hz stimulation every 60 s until a stable plateau of 4–5 contractile responses. Repeat 10Hz stimulation for 5s each was performed with trains of 5ms rectangular pulses at 10volts before and after addition of Acotiamide 1–16μM and evoked contraction amplitude was normalized to the peak response obtained after application of iso-osmolar solution of 120mM potassium chloride. In separate strips, cumulative concentration-response (0.05–10μM) of Carbachol (CCH) were evoked in absence and presence of acotiamide 2μM. Concentration dependent effect of acotiamide and bethanechol on the spontaneous contractions evoked by 10mN of tension were compared. Additional strips were left untreated to monitor any time dependent changes in contractility.

Human bladder-

Human bladder from deceased organ donors (n=3) were procured from the local tissue bank in compliance with the tissue bank IRB#0506140 and the Committee for Oversight of Research and Clinical Training Involving Decedents (CORID # 400) within 4 hours of brain death. Honest broker system of tissue bank does not permit them share disease information of the organ donors and were therefore presumed normal. Removed whole bladders were kept in ice-cold Kreb’s solution till its dissection for isometric tension studies performed within 24h of organ removal. Bladder was cleaned of fat and connective tissues and mucosa intact strips were immersed in 20 mL organ baths for frequency response curve and repeat 10Hz stimulation as described for rat bladder.

Statistical analysis:

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and differences were considered statistically significant with p<0.05. Statistical significance for frequency response curve in EFS was analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test, preferred over Tukey’s test for its higher power. Paired Student’s t test was used for analyzing the contraction amplitude differences evoked by repeat 10Hz stimulation. Carbachol concentration-response curves were analyzed by fitting sigmoidal curves to the experimental data analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results:

Rat bladder-

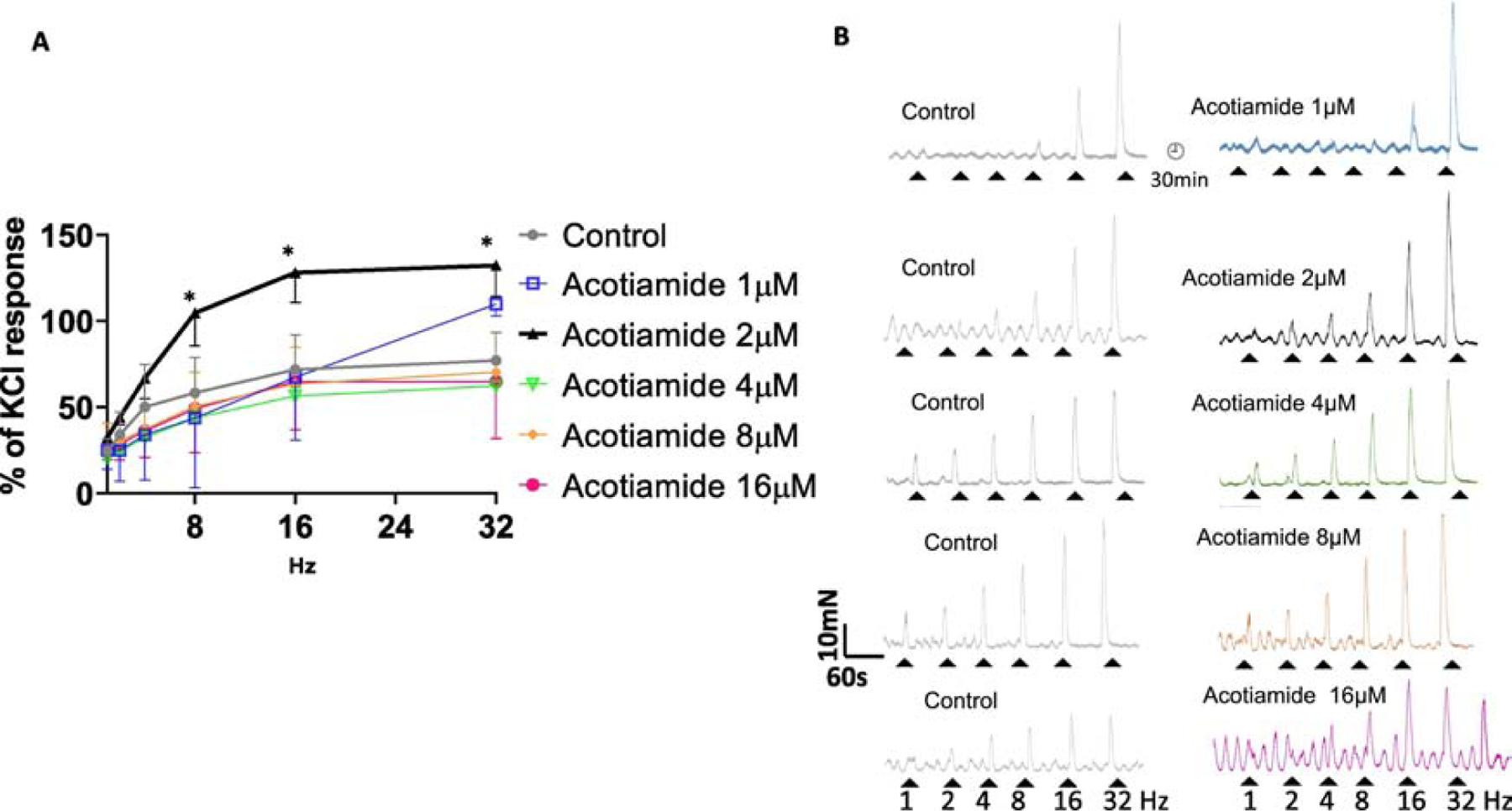

Marked inhibition of frequency-response curves of mucosa intact rat bladder strips in presence of 1 μM TTX demonstrate that evoked contractile responses in our findings were of neurogenic origin. Prior incubation of the strips with acotiamide 2μM significantly enhanced the EFS contractions evoked at 8–32Hz by >50% with respect to the EFS evoked contraction amplitude measured before the addition of acotiamide (Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison with respect to only control group; p<0.01). Differences in the number of separate strips used for evaluating acotiamide effect at different concentrations together with the absence of any excitatory effect of acotiamide >2μM on EFS evoked contraction precluded the comparison between different drug concentrations (Fig.2A–B). TTX sensitivity of the acotiamide 2μM mediated enhancement on EFS evoked contraction and the absence of any enhancement > 2μM together imply that antagonism of pre-junctional receptors by Acotiamide upto 2μM produces a maximal excitatory effect, whereas dominance of antagonist action on post-junctional receptors at higher concentrations may counter the excitatory effect of acotiamide on evoked contractions noticeable at lower concentrations. A similar lack of concentration dependent change with acotiamide was also noted on spontaneous contractions as described later.

Fig 2:

Effect of acotiamide on EFS frequency response curve of rat bladder at different concentrations. Panel A- Acotiamide 2μM (black curve) shifted the frequency response curve to the left of control (grey curve). A >50% increase in the magnitude of EFS contractions evoked at 8–32Hz (Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison with respect to only the control group; *p<0.01; n=7 strips) was dramatically reduced for contractions evoked at frequencies <8Hz. Panel B- Raw traces of TTX-sensitive EFS evoked contractile responses in separate strips evoked before (control grey traces) and in presence of acotiamide at different concentrations (colored traces) illustrates that the prejunctional action of acotiamide at concentration > 2μM is countered by action at other receptors.

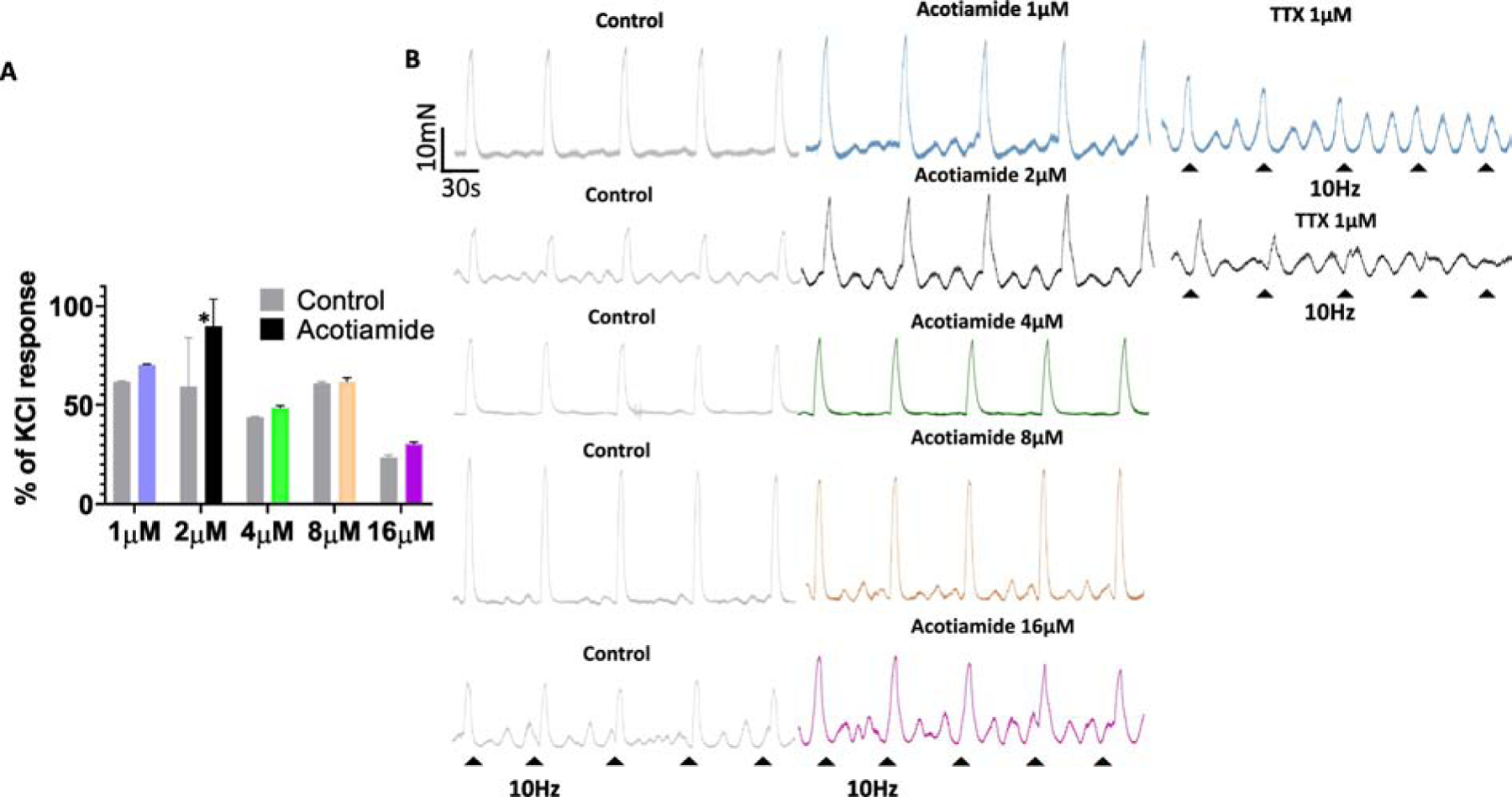

Considering that atropine sensitive (ACh mediated) nerve evoked contractile response is dominant at EFS frequencies ≥ 10Hz (Braverman et al., 1998, Kashyap et al., 2018), we performed paired analysis of responses evoked by repeat 10Hz EFS at different concentrations of Acotiamide (Fig.3A). Paired analysis revealed ~ 50% enhancement with Acotiamide 2μM (Two tailed Student’s t test; p<0.05) (Fig. 2B). Considering that only a slight ~ 5% enhancement is observed at higher concentrations, observed findings argue for a prejunctional action of acotiamide, which is supported by the absence of any excitatory effect in presence of TTX (Fig. 3A) or atropine (data not shown).

Fig 3:

Effect of acotiamide on nerve evoked contraction elicited by repeated 10Hz stimulation. Panel A - Paired analysis of contractile responses evoked by repeat 10Hz EFS at different acotiamide concentrations revealed a significant enhancement after 30min of incubation with acotiamide 2μM (Two tailed Student’s t test. *p<0.05; n=4 strips) but not at higher concentrations. Panel B- Raw traces of EFS evoked contractile responses in separate strips evoked by repeat 10Hz EFS before (control grey traces) and in the presence of acotiamide at different concentrations and after addition of TTX 1μM together support a pre-junctional action site for acotiamide and the neurogenic origin of elicited responses.

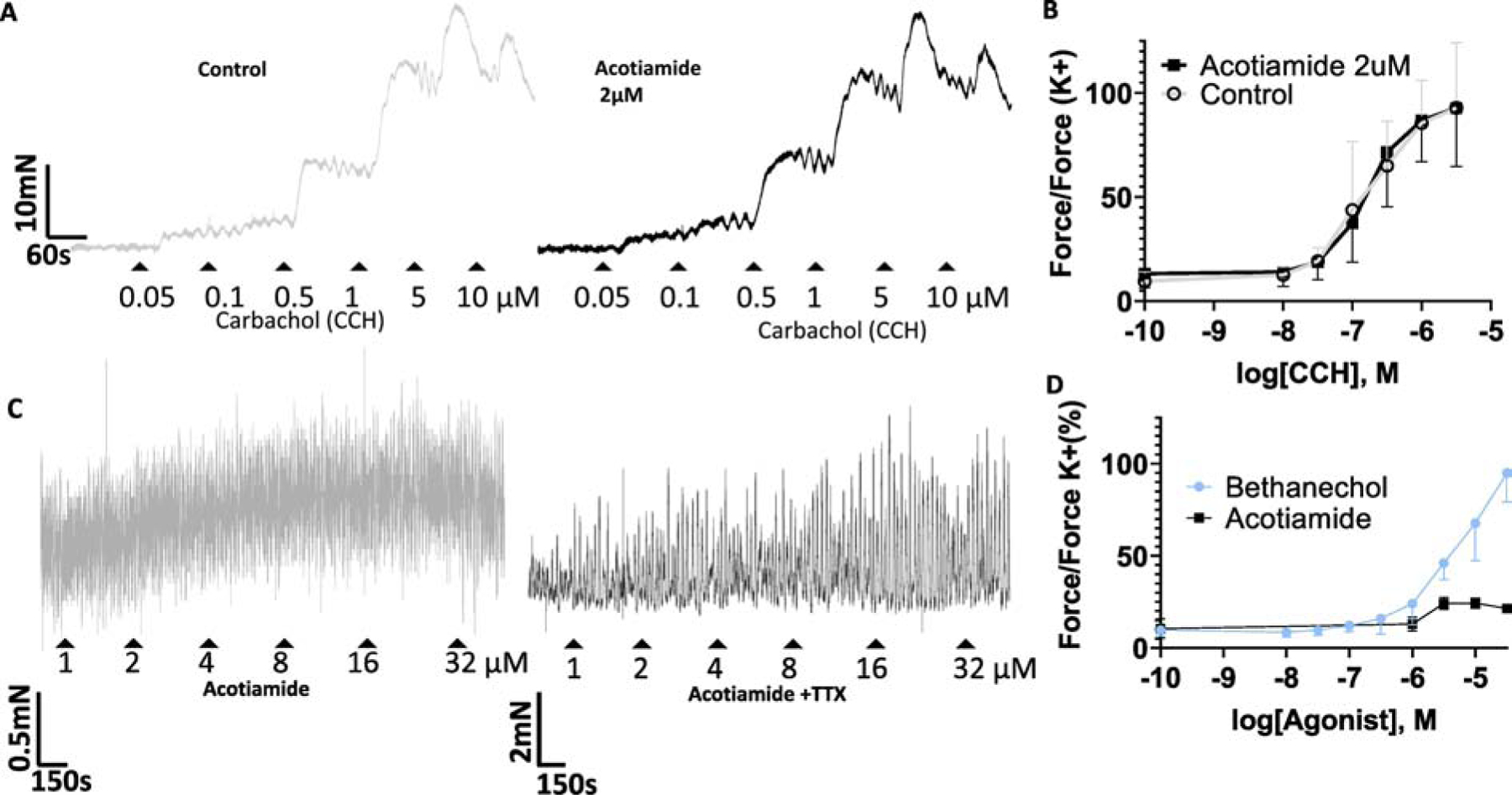

Effects of Acotiamide on carbachol response- Complete overlap of cumulative carbachol concentration-response curve constructed in the absence and in presence of acotiamide 2 μM indicates that acotiamide 2 μM does not oppose post-junctional muscarinic receptor stimulation(Fetscher et al., 2002). Carbachol concentration necessary for generating a 50% of maximal response (EC50) only showed an insignificant increase from 171nM to 197nM in presence of acotiamide without any change in the maximal response (Fig. 4A–B). These findings are consistent with earlier findings where acotiamide in concentration upto 100 μM failed to functionally antagonize recombinant M3 receptors expressed on oocytes (Doi et al., 2004).

Fig 4:

Effect of acotiamide on carbachol evoked and spontaneous contractions. Panel A- Raw traces for cumulative carbachol concentration-response curve constructed in absence (grey tracing) and in presence of acotiamide 2 μM (black tracing). Panel B- Logarithmic concentration response curve of Carbachol evoked contraction in absence (grey curve) and in presence of acotiamide 2 μM (black curve) did not change appreciably. EC50 and amplitude of maximum contraction remained unchanged in n=4 strips. Panel C- Concentration dependent effects of acotiamide on spontaneous contractions of isolated rat bladder strips. Raw traces of spontaneous contractility following cumulative addition of acotiamide 1–32 μM in absence (grey trace) and in presence of TTX 1μM (black trace). Acotiamide raised basal tension two-fold relative to pre-drug levels but failed to produce a concentration dependent rise in tension associated with Carbachol/Bethanechol. Panel D- Summarized integral force calculations indicate that compared to bethanchcol, acotiamide does not produce a concentration dependent increase in tonic activity. Notice the difference in scale bar for the contraction force in panel C relative to panel A and B.

Effects of Acotiamide on spontaneous contractions- Cumulative concentration dependent addition of acotiamide only moderatly affected the spontaneous contractions (Fig. 3C) compared to bethanechol, which mimics the Carbachol effect (Fig. 4A). Tracings and the summarized integral force calculations (Fig. 4D) together indicates that acotiamide fails to generate a concentration dependent increase in the tonic activity as observed with Carbachol (Fig. 4A–B) or Bethanechol. Since a minimal effect of acotiamide on the spontaneous phasic activity becomes more pronounced in presence of TTX, it can be argued that a pre-junctional action of acotiamide may counter a direct excitatory effect of Acotiamide on post-junctional muscarinic receptors for eliciting spontaneous phasic contractions. Importantly, TTX does not influences the modest increase in baseline tone generated by acotiamide which suggests that rise in basal tension and phasic contractions are likely mediated by the action of acotiamide on pre-junctional and post-junctional receptors, respectively (Fig. 4C–D).

Human bladder-

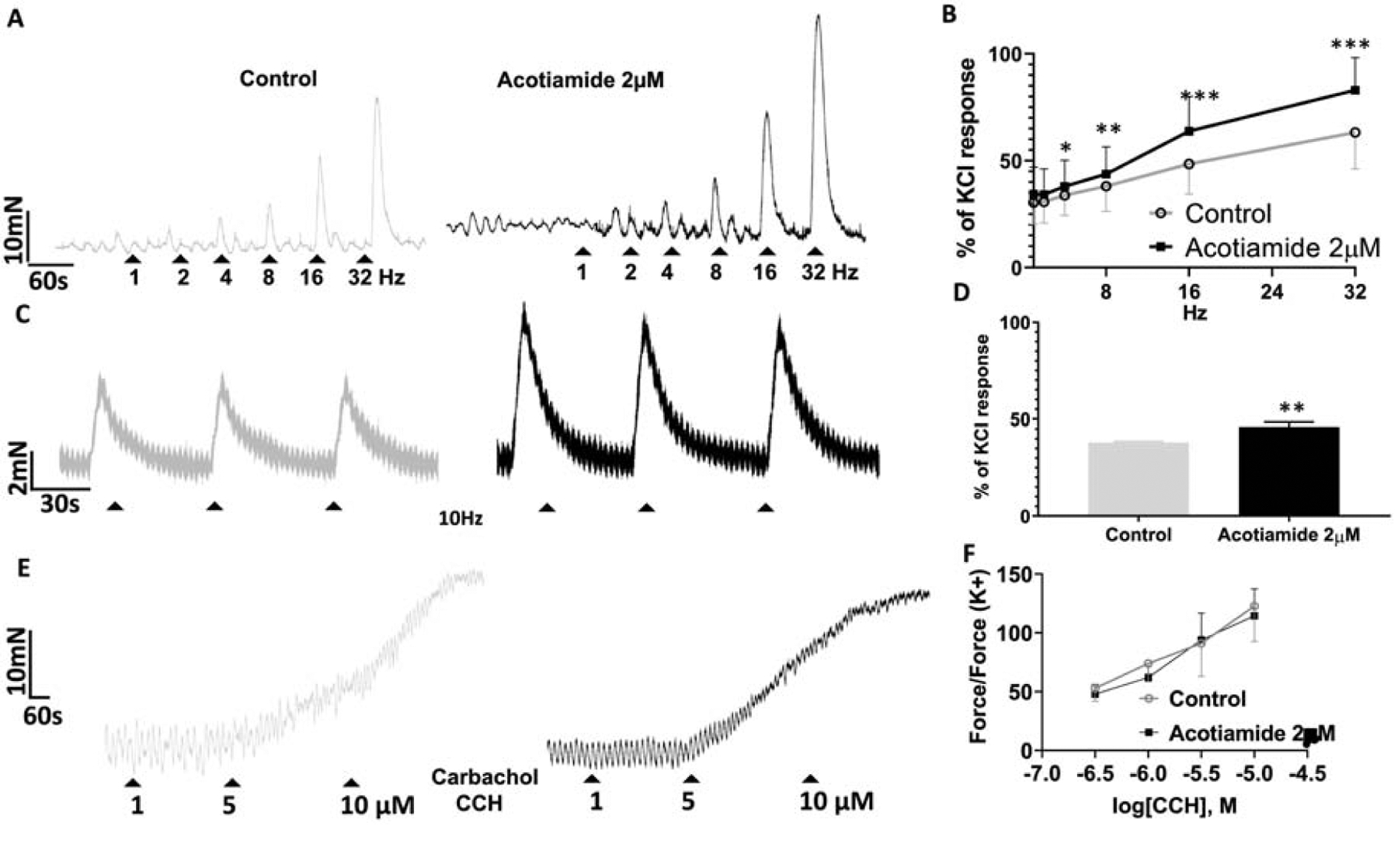

Frequency-response curves of human bladder constructed before and after incubation of acotiamide 2μM showed a significant enhancement of the evoked contractile response >4Hz (Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison; p<0.05; Fig.5B). Importantly, the magnitude of enhancement was ~20% in the atropine sensitive (ACh mediated) range for nerve evoked contractile responses elicited with 16–32Hz stimulation (p<0.0001) as well as on repeat 10Hz stimulation (Two tailed paired Student’s t test. p<0.01) (Fig.5D). Limited availability of human bladder precluded the evaluation of acotiamide effect at higher concentrations. Acotiamide 2μM did not oppose the human bladder contractility evoked by carbachol with only a minor change in EC50(Fig.5E), which was in the range reported by other groups (Fetscher et al., 2002). Effect of acotiamide 2μM on carbachol evoked response and the absence of any effect in absence of EFS is consistent with a prejunctional site of action for acotiamide in human bladder.

Fig 5:

Excitatory effect of acotiamide 2μM on nerve evoked contraction of human bladder. Panel A- Raw traces of EFS frequency-response curves 1–32Hz constructed before (grey tracing) and in presence of acotiamide 2μM (black tracing). Panel B- Acotiamide 2μM (black curve) shifted the frequency response curve to the left of control (grey curve) with a significant ~20% enhancement of atropine sensitive (ACh mediated) nerve evoked contractile responses elicited by 16–32Hz stimulation (***p<0.0001; Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison; 4 strips). Panel C- Raw traces for repeat 10Hz stimulation before (grey tracing) and after addition of acotiamide 2μM (black tracing). Panel D- Paired analysis of contractile responses demonstrate a significant enhancement by acotiamide 2μM (Two tailed paired Student’s t test. *p<0.01). Panel E- Raw traces for cumulative carbachol concentration-response curve constructed in absence (grey tracing) and in presence of acotiamide 2 μM (black tracing). Panel F- Concentration response curve of Carbachol induced contraction in absence (grey curve) and in presence of acotiamide 2 μM (black curve) did not change appreciably. Higher magnitude of carbachol evoked response relative to EFS evoked response is evident from the differences in scale for y-axis in panel F with respect to panel B and D.

Discussion

This is a first report demonstrating a direct excitatory effect of Acotiamide on the neural modulation of rat and human bladder contractility mainly through prejunctional mechanisms (Ogishima et al., 2000). Acotiamide is known to decrease the PVR of DU patients and resolve urinary retention of female patients with thrice daily oral treatment of 100 mg for 2 weeks (Sugimoto et al., 2019, Sugimoto et al., 2017, Sugimoto et al., 2015). Clinically used dose of acotiamide (Sugimoto et al., 2017, Sugimoto et al., 2015) is said to generate plasma concentration in the range of 2μM (Yoshii et al., 2016). Since we tested acotiamide within a concentration range around 2μM in an ex vivo experimental setup, the findings described here are easily translatable to the bedside.

Several studies have demonstrated that voiding contraction in mammals can be experimentally evoked by EFS of parasympathetic nerve with 1ms pulses of 50V at 32Hz (Zeng et al., 2012), which is considered to elicit the release of ACh (D’ Agostino et al., 2015, Tyagi et al., 2017, Yossepowitch et al., 2001) and therefore support the use of EFS for testing the excitatory effect of acotiamide in bladder. Given that EFS evokes a frequency dependent release of neurotransmitters from post-ganglionic nerves of bladder with the dominant release of ATP and of ACh at frequencies ≤ 10Hz(Braverman et al., 1998) and at ≥ 10Hz, respectively (Kashyap et al., 2018), we infer that the significant excitatory effect of acotiamide 2μM on EFS evoked contractions of rat and human bladder elicited by EFS frequencies >8Hz represent an enhancement of cholinergic neurotransmission in bladder.

Since prejunctional receptors on cholinergic nerve terminals exerts either a positive(Braverman et al., 1998, Somogyi et al., 1994) or a negative(D’Agostino et al., 2000) auto-feedback on evoked ACh release, an excitatory effect of acotiamide 2μM on TTX-sensitive evoked contractions of rat and human bladder implicates a suppression of autoinhibitory mechanisms involved in ACh release. The implication is supported by the absence of any excitatory effect on rat and human bladder contractility in absence of EFS. An inhibitory role for the prejunctional muscarinic receptors in bladder was first noted with the inhibition of EFS evoked ACh outflow by the non-selective muscarinic agonist, carbachol (Somogyi et al., 1994). Simultaneous measurement of EFS evoked ACh outflow and contraction amplitude uncovered that non-selective agonism of the prejunctional M2 and M4 auto-receptors by carbachol or by its congener (bethanechol) exerts a negative feedback on the EFS evoked ACh release(Somogyi et al., 1994), which eventually reduces the detrusor contraction amplitude(D’ Agostino et al., 2015, D’Agostino et al., 2000) to produce lower voided volumes and bladder filling compliance during cystometry(Nagabukuro et al., 2004). A separate study suggested that a decrease in PVR of bethanechol treated obstructed rats was caused by an increase in voiding frequency (Hashimoto et al., 2005).

Acotiamide is known to bind to most muscarinic receptors with the IC50 in the range of 1.8–10μM(Doi et al., 2004) except for M3 receptors, which rules out any direct stimulation of post-junctional receptors in the excitatory effect of Acotiamide 2μM, reported here. Earlier studies on Xenopus showed that Acotiamide competitively inhibits the inwards currents mediated by cloned M1 and M2 receptors and nicotinic ACh receptor-mediated inward currents were uncompetitively inhibited at concentrations >10−6 M (Kanemoto et al., 2002). The lack of antagonism for M3 receptors by acotiamide may contribute to the observed acotiamide mediated enhancement of excitatory neurotransmission in bladder as well as in gastrointestinal tract (Doi et al., 2004). Lower affinity for M3 receptors justifies the use of acotiamide as a useful tool to distinguish M1 and M2 receptor-mediated responses from muscarinic M3 receptor-mediated responses. Since concentrations of acotiamide > 2μM is likely to antagonize both pre- and post-junctional muscarinic receptors (Braverman et al., 1998), classical receptor antagonism studies are not possible with Acotiamide with only measurement of isometric tension.

Excitatory effect of acotiamide on evoked contractions of rat and human bladder is also supported by a similar enhancement in the amplitude of twitch-like contractions and excitatory junction potentials (EJPs) evoked by single or repetitive EFS in the circular muscle strips of the guinea-pig stomach (Ogishima et al., 2000). The excitatory effect of acotiamide is linked to the acceleration of TTX-sensitive and extracellular Ca2+ dependent EFS evoked ACh release in the [3H]-choline-preincubated gastric antrum and body of rat and dog at doses greater than 10−6 M (Ogishima et al., 2000). Moreover, acotiamide mediated enhancement of EFS evoked ACh release was higher in the presence of physostigmine, which suggests that direct AChE inhibition by acotiamide (Doi et al., 2004) may have modest contribution to the efficacy of acotiamide in DU patients (Sugimoto et al., 2019, Sugimoto et al., 2017, Sugimoto et al., 2015) and in the findings described here.

Cholinergic transmission is not only critical for voiding but is also critical in maintenance of the bladder tone during storage phase as nerve evoked ACh release (D’Agostino et al., 1989) for accomplishing voiding is 300 times higher than the ACh released in basal mode for volume sensation and maintenance of bladder tone during the storage phase (Zagorodnyuk et al., 2009). Infact, several studies have now suggested that age dependent changes in the release of ATP and ACh (Yoshida et al., 2004) are linked to the defective volume sensation and impaired voiding in aged male rat (Zhao et al., 2010) and in aged UAB/DU patients (Smith et al., 2015). Quantitative differences in ACh release during storage and voiding phase may explain the inferiority of a direct cholinergic agonist like bethanechol (Nagabukuro et al., 2004) over an indirect agonist, because an indirect agonist can efficiently modulate the intensity of cholinergic stimulation from low to high level for storage and voiding phases, respectively whereas, a similar intensity of exogeneous cholinergic stimulation during storage and voiding phase may contribute to the ineffectiveness of a direct cholinergic agonist like bethanechol in PVR reduction of UAB patients (Izumi et al., 2014).

Moderate excitatory effect of acotiamide on spontaneous contractions compared to bethanechol argues against the non-selective agonism of pre-junctional and post-junctional muscarinic receptors in UAB treatment. Modest effect of acotiamide on basal tone in contrast to bethanchol suggests that the excitatory action of acotiamide on spontaneous ACh release via antagonism of pre-junctional M2 receptors (Zagorodnyuk et al., 2009) is countered by the simultaneous antagonism of post-junctional M2 receptors. Therefore, an direct excitatory effect of acotiamide in bladder is in agreement with the expression of M2 muscarinic receptors in rat and human bladder (Tyagi et al., 2006) and the purported functional role of prejunctional M2 receptors in homeostatic regulation of voiding contraction (Braverman et al., 2006). However, these results of acotiamide do not exclude the possible involvement of muscarinic M4 receptors(Takeuchi et al., 2008).

Taking our experimental findings and the clinical results (Sugimoto et al., 2019, Sugimoto et al., 2017, Sugimoto et al., 2015) together, it is likely that the excitatory effect of acotiamide in bladder may involve action on nicotinic autoreceptors on cholinergic nerve terminals (Prior and Singh, 2000), which warrants investigation in future studies. Several clinical studies have now compared the direct and indirect cholinergic agonists in UAB patients with intact voiding reflex and reported that indirect cholinergic agonist like Distigmine works better than Bethanechol (Izumi et al., 2014). Although cholinomimetic agonism of the post-junctional muscarinic receptors by carbachol or bethanechol is desirable during voiding phase, same cholinomimetic action during storage phase is suggested to increase the basal tone (D’Agostino et al., 2000), which decreases the bladder compliance and contributes to the ineffectiveness of Bethanechol in UAB patients (Izumi et al., 2014). Nonetheless, bethanechol effectively decreases the duration of urethral catheterization following transient loss of voiding reflex during postoperative and postpartum nonobstructive urinary retention and in patients with acontractile detrusor (Hirotsu et al., 1998). Acotiamide is an indirect cholinergic agonist like distigmine (Izumi et al., 2014) and clinical experience with acotiamide in DU patients is predictive of its efficacy in UAB patients. Infact, acotiamide was effective in reducing the PVR of DU patients non-responsive to distigmine (Sugimoto et al., 2015), suggesting that differences in mechanism of action of acotiamide and distigmine is of therapeutic relevance in aged UAB patients.

Conclusions-

This is the first report demonstrating the direct excitatory effect of Acotiamide on neural modulation of rat and human bladder contractility in an ex vivo setup. These findings are consistent with PVR reduction in Acotiamide treated DU patients and highlight that antimuscarinics selective for M3 receptors and those lacking any action on M3 receptors are promising for OAB and UAB treatment, respectively.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grant awarded by NIA-AG062971

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Braverman AS, Doumanian LR, Ruggieri MR Sr. M2 and M3 muscarinic receptor activation of urinary bladder contractile signal transduction. II. Denervated rat bladder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;316:875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman AS, Kohn IJ, Luthin GR, Ruggieri MR. Prejunctional M1 facilitory and M2 inhibitory muscarinic receptors mediate rat bladder contractility. Am J Physiol 1998;274:R517–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’ Agostino G, Maria Condino A, Calvi P. Involvement of beta3-adrenoceptors in the inhibitory control of cholinergic activity in human bladder: Direct evidence by [(3)H]-acetylcholine release experiments in the isolated detrusor. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;758:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino G, Bolognesi ML, Lucchelli A, Vicini D, Balestra B, Spelta V, et al. Prejunctional muscarinic inhibitory control of acetylcholine release in the human isolated detrusor: involvement of the M4 receptor subtype. Br J Pharmacol 2000;129:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino G, Chiari MC, Grana E. Prejunctional effects of muscarinic agonists on 3H-acetylcholine release in the rat urinary bladder strip. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1989;340:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi Y, Murasaki O, Kaibara M, Uezono Y, Hayashi H, Yano K, et al. Characterization of functional effects of Z-338, a novel gastroprokinetic agent, on the muscarinic M1, M2, and M3 receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 2004;505:31–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetscher C, Fleichman M, Schmidt M, Krege S, Michel MC. M(3) muscarinic receptors mediate contraction of human urinary bladder. Br J Pharmacol 2002;136:641–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Nagabukuro H, Doi T. Effects of the selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor TAK-802 on the voiding behavior and bladder mass increase in rats with partial bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol 2005;174:1137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu I, Hayano C, Tani T. Effect of muscarinic agonist on overflow incontinence induced by bilateral pelvic nerve transection in rats. Jpn J Pharmacol 1998;76:109–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Maolake A, Maeda Y, Shigehara K, Namiki M. Effects of bethanechol chloride and distigmine bromide on postvoiding residual volume in patients with underactive bladder. Minerva Urol Nefrol 2014;66:241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemoto Y, Ishibashi H, Doi A, Akaike N, Ito Y. An electrophysiological study of muscarinic and nicotinic receptors of rat paratracheal ganglion neurons and their inhibition by Z-338. Br J Pharmacol 2002;135:1403–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap M, Pore S, Chancellor M, Yoshimura N, Tyagi P. Bladder overactivity involves overexpression of MicroRNA 132 and nerve growth factor. Life Sci 2016;167:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap MP, Pore SK, de Groat WC, Chermansky CJ, Yoshimura N, Tyagi P. BDNF overexpression in the bladder induces neuronal changes to mediate bladder overactivity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2018;315:F45–F56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DK. Current pharmacological and surgical treatment of underactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol 2017;58:S90–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills IW, Greenland JE, McMurray G, McCoy R, Ho KM, Noble JG, et al. Studies of the pathophysiology of idiopathic detrusor instability: the physiological properties of the detrusor smooth muscle and its pattern of innervation. J Urol 2000;163:646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagabukuro H, Okanishi S, Doi T. Effects of TAK-802, a novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, and various cholinomimetics on the urodynamic characteristics in anesthetized guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol 2004;494:225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. EAU guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol 2013;64:118–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogishima M, Kaibara M, Ueki S, Kurimoto T, Taniyama K. Z-338 facilitates acetylcholine release from enteric neurons due to blockade of muscarinic autoreceptors in guinea pig stomach. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000;294:33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior C, Singh S. Factors influencing the low-frequency associated nicotinic ACh autoreceptor-mediated depression of ACh release from rat motor nerve terminals. Br J Pharmacol 2000;129:1067–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CP, Boone TB, de Groat WC, Chancellor MB, Somogyi GT. Effect of stimulation intensity and botulinum toxin isoform on rat bladder strip contractions. Brain Res Bull 2003;61:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PP, Chalmers DJ, Feinn RS. Does defective volume sensation contribute to detrusor underactivity? Neurourol Urodyn 2015;34:752–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi GT, Tanowitz M, de Groat WC. M1 muscarinic receptor-mediated facilitation of acetylcholine release in the rat urinary bladder. J Physiol 1994;480 (Pt 1):81–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Akiyama T, Matsumura N, Minami T, Uejima S, Uemura H. Efficacy of acotiamide hydrochloride hydrate added to alpha-blocker plus cholinergic drug combination therapy. Int J Urol 2019;26:848–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Akiyama T, Shimizu N, Matsumura N, Hashimoto M, Minami T, et al. Acotiamide hydrochloride hydrate added to combination treatment with an alpha-blocker and a cholinergic drug improved the QOL of women with acute urinary retention: case series. Res Rep Urol 2017;9:141–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Akiyama T, Shimizu N, Matsumura N, Hayashi T, Nishioka T, et al. A pilot study of acotiamide hydrochloride hydrate in patients with detrusor underactivity. Res Rep Urol 2015;7:81–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T, Yamashiro N, Kawasaki T, Nakajima H, Azuma YT, Matsui M. The role of muscarinic receptor subtypes in acetylcholine release from urinary bladder obtained from muscarinic receptor knockout mouse. Neuroscience. 2008;156:381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi P, Kashyap M, Yoshimura N, Chancellor M, Chermansky CJ. Past, Present and Future of Chemodenervation with Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Overactive Bladder. J Urol 2017;197:982–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi P, Mizoguchi S, Chermansky C., Yoshimura N. Excitatory Effect of Acotiamide on Nerve Evoked Contractions of Rat and Human Bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2019. p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi S, Tyagi P, Van-le S, Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB, de Miguel F. Qualitative and quantitative expression profile of muscarinic receptors in human urothelium and detrusor. J Urol 2006;176:1673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Miyamae K, Iwashita H, Otani M, Inadome A. Management of detrusor dysfunction in the elderly: changes in acetylcholine and adenosine triphosphate release during aging. Urology. 2004;63:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii K, Iikura M, Hirayama M, Toda R, Kawabata Y. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Modeling for the Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase by Acotiamide, A Novel Gastroprokinetic Agent for the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia, in Rat Stomach. Pharm Res 2016;33:292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yossepowitch O, Gillon G, Baniel J, Engelstein D, Livne PM. The effect of cholinergic enhancement during filling cystometry: can edrophonium chloride be used as a provocative test for overactive bladder? J Urol 2001;165:1441–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorodnyuk VP, Gregory S, Costa M, Brookes SJ, Tramontana M, Giuliani S, et al. Spontaneous release of acetylcholine from autonomic nerves in the bladder. Br J Pharmacol 2009;157:607–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Pan C, Jiang C, Lindstrom S. Cause of residual urine in bladder outlet obstruction: an experimental study in the rat. J Urol 2012;188:1027–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Aboushwareb T, Turner C, Mathis C, Bennett C, Sonntag WE, et al. Impaired bladder function in aging male rats. J Urol 2010;184:378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]