Abstract

Objective:

To investigate 6-month non-intervention follow-up effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for weight bias internalization (WBI; i.e., self-stigma) combined with behavioral weight loss (BWL).

Methods:

Adults with obesity and elevated WBI were previously randomized to receive BWL alone or combined with the Weight Bias Internalization and Stigma Program (BWL+BIAS). Participants attended weekly group meetings for 12 weeks, followed by 2 bi-weekly and 2 monthly meetings (26 weeks total). Follow-up assessments were conducted at week 52. Changes on the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS) and Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) at week 52 were the principal outcomes. Other outcomes included changes in eating, coping, and weight.

Results:

Of seventy-two randomized participants, 54 (75%) completed week 52 assessments. Linear mixed models showed improvements across groups, but no significant differences between groups, in week 52 change on the WBIS (p=0.25) or WSSQ (p=0.27). BWL+BIAS participants reported significantly greater benefits than BWL participants on measures of eating and affective coping with weight stigma. Percent weight loss at week 52 did not differ significantly between groups (BWL+BIAS=−3.1±1.0%, BWL=−4.0±1.0%, p=0.53).

Conclusions

Reductions in WBI did not differ between groups at 6-month follow-up. Further research is needed to determine the potential benefits of a stigma-reduction intervention beyond BWL.

Keywords: Obesity, stigma, weight loss

Introduction

Weight bias internalization (WBI), also referred to as weight self-stigma, occurs when individuals with a higher body weight are aware of derogatory societal messages about weight, begin to apply negative weight stereotypes to themselves and, as a result, have lower self-worth due to their weight (1). WBI is associated with an array of adverse mental and physical health outcomes including depression, anxiety, disordered eating, reduced engagement in health-promoting behaviors, and potentially impaired weight management efforts (2). However, little is known about 1) how to reduce WBI and 2) how its reduction might affect health outcomes.

The Weight Bias Internalization and Stigma (Weight BIAS) Program was designed to reduce WBI and help individuals with obesity cope with weight stigma (3). In a previously published report, the Weight BIAS Program, in combination with standard behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatment, compared to BWL alone, produced significantly greater reductions in self-devaluation due to weight on one measure of WBI due to weight after 12 and 26 weeks of treatment (4; see Table 1 for abbreviation legend). Additional benefits were found for reductions in self-reported hunger at weeks 12 and 26. Weight loss and other measures of WBI, psychosocial well-being, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk did not differ significantly between conditions but improved in both.

Table 1.

Abbreviation Key

| WBI | Weight bias internalization |

| BWL | Behavioral weight loss |

| BWL+BIAS | Behavioral weight loss + the Weight Bias Internalization and Stigma Program |

| WBIS | Weight Bias Internalization Scale |

| WSSQ | Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire |

The current study tested the effects on WBI (primary outcome) of the BWL+BIAS intervention, compared to BWL, on WBI at a 6-month non-intervention follow-up (i.e., week 52). Effects of the BWL+BIAS intervention at week 52 on other psychosocial, behavioral, and CVD outcomes were also assessed. Given the common experience of post-treatment weight regain (5), post-hoc analyses examined the relationship between changes in WBI and weight.

Methods

Participants

Participants were men and women, ages 18-65 years old, who sought weight loss and had obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30kg/m2). Participants were eligible if they reported a history of experiencing weight bias (teasing/bullying, discrimination, or other unfair treatment due to weight) and elevated levels of WBI, as indicated by a score of 4.0 or greater on the Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS; 1). Applicants had to confirm in an in-person interview, conducted by a psychologist, that their weight negatively affected how they felt about themselves (see reference 4 for other study inclusion/exclusion criteria).

Procedures

Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio, in blocks of 2 and 4, to either the BWL+BIAS group or the standard BWL group (described below). Participants remained in their same group throughout the duration of the program, with no interaction between participants in the two conditions. The random allocation sequence was generated by a collaborator who was not involved in the conduct of the trial, and participants were assigned to their condition by a staff member who was blinded to the allocation sequence. Participants and study investigators/staff were not blinded to group assignments after randomization (and the principal investigator also served as a group leader and supervised treatment delivery). Recruitment occurred from April to October 2018; treatment and data collection for the 26-week intervention occurred from May 2018 to April 2019; and 6-month (week 52) non-intervention follow-up data were collected from April to October 2019.

Intervention

All participants attended 90-minute group meetings, which consisted of 11-13 participants and were led by a psychologist or registered dietitian at an academic weight management center. Participants received 12 weekly group sessions, followed by 2 every-other-week sessions and 2 monthly sessions (16 sessions over 26 weeks). Participants in both groups were provided with 60 minutes of BWL treatment, based on the Diabetes Prevention Program (6) and LEARN Program (7). A goal of 1200-1499 kcal per day was prescribed for participants <250 lb and 1500-1800 kcal for those ≥250 lb (8, 9). Participants were instructed to eat a balanced diet and to record their daily food and caloric intake. Weight was measured at every group session. Session topics during the first 12 weeks included self-monitoring, stimulus control, social support, portion sizes, and goal-setting. Group sessions during weeks 13-26 focused on skills required for weight loss maintenance and relapse prevention. Physical activity prescriptions began at week 2 and gradually progressed to a goal of 150 minutes per week by week 12 and 200-250 minutes per week by week 26. Moderate intensity was prescribed, with an emphasis on walking. At the end of treatment, participants were provided with referrals to other weight management programs for continued support with weight loss maintenance if desired.

In the BWL+BIAS group, an additional 30 minutes each session (8 hours total) was devoted to stigma content. Content was adapted from cognitive-behavioral therapy and “third-wave” therapies, such as dialectical behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy. Session topics included: psychoeducation about weight and weight bias; challenging myths/stereotypes and cognitive distortions related to weight; the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (with an emphasis on weight management behaviors); restructuring negative thoughts and reappraising stigmatizing situations; interpersonal effectiveness skills; increasing self-efficacy; reducing self-criticism; and increasing empowerment, self-compassion, and body and self-acceptance (4). In the standard BWL group, an additional 30 minutes was devoted each session to discussing recipes and food preparation, allowing for equal time spent in group sessions across conditions, without giving additional weight loss counseling to the standard BWL group.

Outcome Measures

All outcomes were measured at screening/baseline and weeks 12, 26, and 52. Results from weeks 12 and 26 have been previously published (4). The current report focuses on week 52 results.

Primary outcome.

Participants completed the WBIS, which includes 11 items rated on a 1-7 scale (scores averaged, with higher scores indicating greater WBI) (1). The 12-item Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire (WSSQ) was included as a secondary measure of WBI, with items rated from 1-5 and summed, producing a total score and two subscales: Fear of Enacted Stigma (or anticipated experiences of stigma; 6 items) and Self-Devaluation (6 items; 10). The Fat Phobia scale was also included as a measure of weight stereotype endorsement; participants were presented with pairs of adjectives used to describe people with obesity (e.g., fast versus slow) and used a differential rating scale (1–5) to indicate whether or not they agreed with negative weight stereotypes (11). As a process-level outcome, the Coping with Weight Stigma scale (12) was included to determine whether between-group differences emerged in participants’ responses to weight-stigmatizing situations in the past 6 months. In addition to a full scale score (items rated 0-4 and averaged), subscale scores were computed for negative affect, maladaptive eating, exercise avoidance, and healthy lifestyle as responses to weight stigma (specific items described in Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Participant Characteristics and Measures, N (%) or Mean ± Standard Deviation

| Variable | Total (N=72) | BWL+ BIAS (n=36) | BWL (n=36) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.1±11.5 | 47.7±11.4 | 46.6±11.8 | 0.69 |

| Sex | 0.33 | |||

| Female | 61 (84.7%) | 32 (88.9%) | 29 (80.6%) | |

| Male | 11 (15.3%) | 4 (11.1%) | 7 (19.4%) | |

| Race | 0.13 | |||

| White | 21 (29.2%) | 7 (19.4%) | 14 (38.9%) | |

| Black | 48 (66.7%) | 26 (72.2%) | 22 (61.1%) | |

| Asian | 2 (2.8%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0 | |

| Multiracial* | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0 | |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 6 (8.3%) | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.39 |

| Education (years) | 14.9±2.1 | 14.8±2.2 | 15.1±2.0 | 0.61 |

| Weight (kg) | 109.8±22.6 | 112.4±24.0 | 107.2±21.2 | 0.34 |

| Height (cm) | 166.8±8.5 | 167.0±8.7 | 166.6±8.5 | 0.86 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 39.3±6.1 | 40.1±6.5 | 38.4±5.6 | 0.25 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 117.0±14.1 | 119.1±15.3 | 114.9±12.6 | 0.21 |

| Systolic blood pressure+ | 127.7±10.3 | 127.4±10.2 | 128.0±10.7 | 0.50 |

| Diastolic blood pressure+ | 73.7±8.5 | 73.0±9.2 | 74.3±7.9 | 0.26 |

| WBIS | 5.1±0.7 | 5.0±0.7 | 5.2±0.7 | 0.33 |

| WSSQ Total | 38.6±6.7 | 37.9±6.6 | 39.3±6.9 | 0.39 |

| WSSQ-SD | 19.2±4.1 | 19.1±4.2 | 19.2±3.9 | 0.93 |

| WSSQ-FNE | 19.4±4.7 | 18.8±4.6 | 20.1±4.8 | 0.26 |

| Fat Phobia Scale | 3.7±0.6 | 3.7±0.7 | 3.7±0.6 | 0.54 |

| Coping with Weight Stigma | ||||

| Full Scale | 1.9±0.5 | 1.9±0.6 | 2.0±0.4 | 0.27 |

| Negative Affect | 2.4±0.7 | 2.2±0.7 | 2.6±0.7 | 0.02 |

| Maladaptive Eating | 1.4±0.6 | 1.3±0.6 | 1.4±0.5 | 0.44 |

| Exercise Avoidance | 1.9±1.0 | 2.0±1.1 | 1.8±0.9 | 0.50 |

| Healthy Lifestyle | 2.1±0.9 | 2.2±0.8 | 2.0±1.0 | 0.23 |

| PHQ-9 | 8.0±4.8 | 7.5±5.1 | 8.4±4.5 | 0.45 |

| GAD-7 | 5.4±4.3 | 5.6±4.5 | 5.2±4.2 | 0.67 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 17.3±6.4 | 17.6±6.2 | 16.9±6.5 | 0.66 |

| Body Appreciation Scale | 2.6±0.7 | 2.8±0.6 | 2.5±0.7 | 0.11 |

| IWQOL-Lite Total | 55.3±16.5 | 56.3±16.7 | 54.2±16.5 | 0.61 |

| Public Distress Subscale | 63.3±25.6 | 60.0±27.6 | 66.7±23.1 | 0.27 |

| WEL-SF | 40.0±17.5 | 39.4±17.4 | 40.7±17.9 | 0.75 |

| SEE | 51.2±20.0 | 48.3±20.1 | 54.2±19.9 | 0.22 |

| Eating Inventory | ||||

| Dietary Restraint | 8.7±3.7 | 8.5±3.7 | 8.9±3.8 | 0.67 |

| Disinhibition | 9.7±3.3 | 9.2±3.5 | 10.2±3.1 | 0.19 |

| Hunger | 7.1±3.7 | 7.8±3.6 | 6.4±3.6 | 0.10 |

| Self-Reported Weighing | 0.9±1.2 | 0.9±1.2 | 0.9±1.1 | 0.83 |

| Track Food/Drink | 0.5±0.8 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.5±0.8 | 0.70 |

| Track Calories | 0.5±1.0 | 0.4±1.0 | 0.6±1.1 | 0.32 |

| Track Activity | 1.2±1.5 | 1.0±1.5 | 1.3±1.5 | 0.38 |

Note. N=35 for BWL condition for all measures past the WBIS. WBIS=Weight Bias Internalization Scale; WSSQ=Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire; SD=Self-Devaluation; FNE=Fear of Enacted Stigma. Coping with Weight Stigma subscale items were as follows: Negative Affect (feeling badly about one’s body, angry, sad and depressed, worse about oneself, afraid, and a reverse-scored item for not being bothered); Maladaptive Eating (avoided eating in front of others, eating more, binge/overeat, tried diet pills, tried starving, made oneself vomit, and became obsessed with weight); Exercise Avoidance (avoided the gym, avoided exercise, and didn’t feel like exercising); and Healthy Lifestyle (tried to eat healthier foods and started exercising more). PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7=Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; PSS=Perceived Stress Scale; IWQOL-Lite=Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite; SEE=Self-Efficacy to Exercise Scale; WEL-SF=Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire – Short Form.

Secondary outcomes.

Participants completed the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life Questionnaire-Lite (IWQOL-Lite), which assesses weight-specific aspects of psychological and physical functioning (13). Scale items are rated from 1-5 and scores are transformed to a 0-100 scale, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. In addition to the total score, the Public Distress subscale examines perceived weight stigma (higher scores indicate lower public distress). Other subscales include Physical Function, Self-Esteem, Sexual Life, and Work (see Supplementary Table 1). Participants also completed the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to assess symptoms of depression, with summed scores, 0-27 (14), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire, with summed scores, 0-21 (15). In both scales, a score of 10 or higher suggests moderate to severe depression or anxiety. The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale was administered, with higher summed scores (0-40) indicating greater perceived stress (16). The Body Appreciation Scale was included as a measure of body esteem, with 10 items rated 1-5, scores averaged, and higher scores indicating greater body appreciation (17). Other exploratory outcomes can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Behavioral outcome measures included changes in self-efficacy, as assessed by the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire-Short Form (WEL; 18) and the Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale (SEES; 19). The WEL assesses confidence in one’s ability to overcome challenges that lead to overeating, while the SEES assesses confidence to overcome barriers to physical activity. The scales are 8 and 9 items, respectively, with scores summed 0-80 and 0-90, and higher scores indicate greater self-efficacy. Changes in self-reported eating were assessed with the Eating Inventory, which includes subscales for dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger (20). Items include both true/false and rating scales, with all scores converted to 0 or 1 ratings and summed. Participants also reported their frequency of self-weighing and tracking their food/drink intake, calories, and physical activity. Self-reported weighing was rated 0-4 (less than once per month through several times per day); other self-monitoring/tracking behaviors were also rated from 0-4 (from never to everyday).

Duplicate measures of height were obtained at screening using a wall-mounted stadiometer (Veeder-Root, Elizabethtown, NC). Weight was measured in duplicate with a digital scale; Detecto, model 6800A), from which percentage reduction in baseline weight was calculated. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured in duplicate using an automated Dinamap monitor (Johnson & Johnson, XL model 9300) at 1-minute intervals after ≥ 5 minute rest. Waist circumference was measured in duplicate to the nearest 0.1 cm (with a flexible tension-controlled measuring tape) midway between the iliac crest and lowest rib.

Safety and Treatment Acceptability

All study procedures were approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board (IRB), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Study oversight was provided by a Data and Safety Monitor (DSM) who was not involved in the study. Adverse events (AEs) were documented by study staff in consultation with a nurse practitioner and physician, and serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported immediately to the study sponsor, DSM, and IRB. For this extension study, AEs and SAEs were collected at week 52, and AEs affecting ≥5% of participants in either group were identified.

All participants were asked whether they received any form of weight loss treatment in the 6 months between completion of the program and the week 52 assessment. Participants across groups rated (from 1-7) the extent to which they found the program (as a whole) to be helpful and acceptable, and how much they liked, were satisfied with, and would recommend the program to others. These five items were averaged for an overall treatment acceptability score. Participants also rated (1–7) the extent to which: they learned new things; their attitudes about themselves changed; and the program helped with their weight management goals. Five items were included that asked participants to rate (1–7) the extent to which they learned specific weight management strategies (measure portion sizes, calculate calories, track calories, incorporate physical activity into their regular routine, and overcome barriers to physical activity), along with an item that asked how much participants learned to cook with healthy recipes. Participants in both groups also rated (1–7) how much they had learned the skills discussed in the Weight BIAS program (e.g., challenge myths and stereotypes about obesity) and how frequently they used these skills in the past 6 months (ratings from 1[never] to 5[frequently]).

Statistical Analyses

Sample size for the initial trial was determined with a power analysis to detect a medium-size between-group difference in WBIS scores at week 12 (4). Skewness and kurtosis were examined for continuous outcome measures at all time points, and variables were transformed appropriately to meet assumptions of normality. The intention-to-treat principle was used to include all randomized participants in the primary analyses. Linear mixed models were used to compare changes between groups at week 52 on all continuous outcome measures. Piecewise models with breakpoints at weeks 12 and 26 were used to extend the previously described 26-week models (4) to include 52-week data. In addition to reporting between-group differences in change from baseline to week 52 (primary outcome), we also report differences in change from week 26 to week 52.

In a post-hoc analysis, correlations were used to explore the relationship between changes in WBI and percent weight change from baseline to week 52. In addition, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether weight regain of 1 percentage point or more from weeks 26 to 52 was associated with changes in WBIS scores during that time. ANOVAs were also used to compare differences between groups in treatment acceptability ratings and skill acquisition and use. All analyses were conducted with SPSS 25 and tested analyses with a significance level set at p<0.05. Cohen’s d was computed to determine the effect sizes of between-group differences.

Initial Trial Results

Participants were predominantly Black, female, and middle aged, and had class II or III obesity (i.e., BMI of 35-39.9 or ≥40 kg/m2). Participant characteristics and baseline scores are presented in Table 2. As previously reported (4), at week 26, participants in the BWL+BIAS group had an average reduction of 1.5 on the WBIS, compared to 1.3 in the BWL group. This difference was not statistically significant. WSSQ total scores declined significantly more in the BWL+BIAS group than the BWL group at week 12, but not week 26. This effect was primarily driven by significantly greater reductions in WSSQ Self-Devaluation subscale scores in the BWL+BIAS vs. BWL participants at both weeks 12 and 26. Weight losses at week 26 were 4.5% and 5.9%, respectively, and did not differ significantly by condition. BWL+BIAS participants also reported greater reductions in hunger than did BWL participants at weeks 12 and 26.

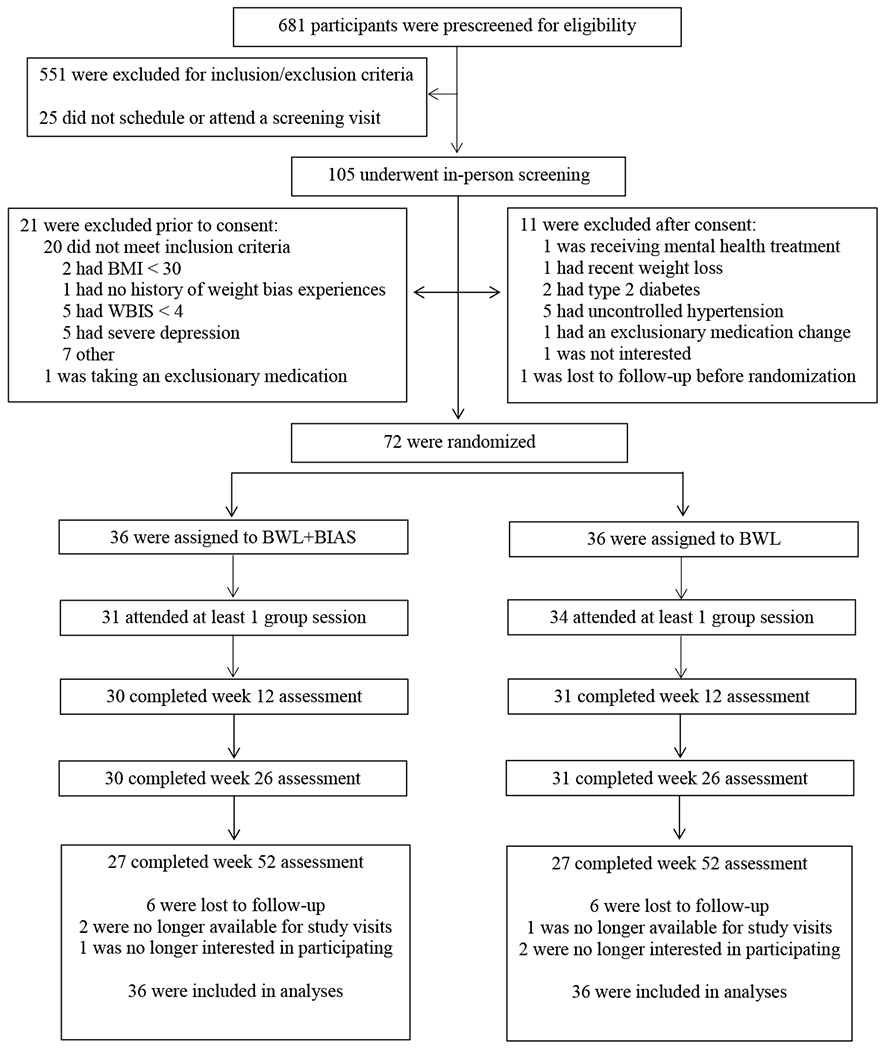

Results

Of the 72 participants randomized (36 per condition), 61 (84.7%) completed week 12 and 26 assessments (BWL+BIAS n=30, BWL n=31), and 54 (75%) completed the week 52 assessment (n=27 per condition) (Figure 1). Of the participants who completed this follow-up assessment, 11.1% reported that they received additional treatment for their weight in the 6 months since completing the program: 5.6% reported participating in a commercial weight loss program; 5.6% received nutrition counseling; 5.6% received prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal weight loss medication or supplements; 5.6% attended a weight loss support group, 1.9% received physician weight management; 7.4% participated in a workplace wellness program; 3.7% used a self-guided program or book (e.g., Slimfast); 7.4% used a personal trainer or attended a program at a fitness center; and 7.4% reported participating in some other kind of weight loss intervention since ending the program. (Many of these participants reported receiving multiple interventions.) No participants reported receiving psychological counseling related to their weight. All randomized participants were included in the primary analyses, in order to ascertain the naturalistic effects when no restrictions were placed on participants’ methods for maintaining their weight loss or psychological well-being.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Weight Stigma

Table 3 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 present estimated changes from baseline to week 26 and to week 52 (as well as from weeks 26 to 52) in WBIS and WSSQ scores (total and subscales). Participants across groups showed significant reductions on the WBIS from baseline to week 52. However, changes in WBIS scores did not differ significantly between the BWL+BIAS and BWL groups from baseline to week 52 (−1.5±0.2 vs. −1.2±0.2). Changes in WSSQ total and subscale scores from baseline also did not differ between groups at week 52, nor did changes in Fat Phobia Scale scores. Participants in the BWL+BIAS group reported significantly greater reductions from baseline to week 52 in negative affect following experiences of weight stigma than did participants in the BWL group (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated mean change (± standard error) in stigma-related outcomes from baseline to Weeks 26 and 52, and from Weeks 26 to 52

| Variable | BWL+BIAS (n=36) | BWL (n=36) | Mean Difference | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBIS | |||||

| Week 26 | −1.5±0.2*** | −1.3±0.2*** | −0.2±0.3 | 0.45 | 0.16 |

| Week 52 | −1.5±0.2*** | −1.2±0.2*** | −0.3±0.3 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.0±0.2 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.55 | 0.15 |

| WSSQ Total | |||||

| Week 26 | −7.1±1.5*** | −3.6±1.5* | −3.5±2.1 | 0.11 | 0.35 |

| Week 52 | −5.6±1.6*** | −3.1±1.6 | −2.5±2.2 | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.5±1.2 | 0.5±1.2 | 0.9±1.6 | 0.57 | 0.14 |

| WSSQ-SD | |||||

| Week 26 | −4.1±0.8*** | −1.5±0.8 | −2.6±1.1 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| Week 52 | −2.9±0.8*** | −1.2±0.8 | −1.8±1.2 | 0.13 | 0.27 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.2±0.7 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.8±1.0 | 0.42 | 0.18 |

| WSSQ-FNE | |||||

| Week 26 | −2.9±0.9** | −2.1±0.9* | −0.8±1.3 | 0.53 | 0.13 |

| Week 52 | −2.7±1.0** | −2.0±1.0* | 0.6±1.4 | 0.65 | 0.09 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.3±0.8 | 0.1±0.8 | 0.2±1.2 | 0.89 | 0.03 |

| Fat Phobia Scale | |||||

| Week 26 | −0.5±0.1*** | −0.2±0.1 | −0.3±0.2 | 0.09 | 0.33 |

| Week 52 | −0.4±0.1** | −0.2±0.1 | −0.2±0.2 | 0.21 | 0.26 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.0±0.1 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.77 | 0.07 |

| Coping with Weight Stigma | |||||

| Full Scale | |||||

| Week 26 | −0.8±0.1*** | −0.9±0.1*** | 0.1±0.2 | 0.61 | 0.10 |

| Week 52 | −0.7±0.1*** | −0.6±0.1*** | −0.1±0.2 | 0.52 | 0.13 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.3±0.1* | −0.2±0.1 | 0.21 | 0.27 |

| Negative Affect+ | |||||

| Week 26 | −1.1±0.1*** | −1.1±0.1*** | 0.0±0.2 | 0.86 | 0.05 |

| Week 52 | −1.2±0.1*** | −0.8±0.1*** | −0.5±0.2 | 0.02 | 0.47 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.1±0.1 | 0.3±0.1* | −0.4±0.2 | 0.07 | 0.40 |

| Maladaptive Eating | |||||

| Week 26 | −0.8±0.1*** | −0.8±0.1*** | 0.0±0.1 | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| Week 52 | −0.6±0.1*** | −0.6±0.1*** | −0.1±0.2 | 0.63 | 0.10 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.2±0.1 | 0.2±0.1* | −0.1±0.2 | 0.58 | 0.12 |

| Exercise Avoidance | |||||

| Week 26 | −0.9±0.2*** | −0.9±0.2*** | 0.0±0.3 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

| Week 52 | −0.7±0.3** | −0.6±0.3* | −0.1±0.4 | 0.74 | 0.07 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.72 | 0.08 |

| Healthy Lifestyle | |||||

| Week 26 | −0.2±0.2 | 0.0±0.2 | −0.2±0.3 | 0.47 | 0.17 |

| Week 52 | −0.2±0.2 | 0.0±0.2 | −0.2±0.3 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.0±0.3 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

Note. Week 26 values from the original report are presented. WBIS=Weight Bias Internalization Scale; WSSQ=Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire; SD=Self-Devaluation; FNE=Fear of Enacted Stigma.

Coping with Stigma-Negative Affect values differed at baseline, so models were examined with change scores, controlling for baseline values (centered at mean). Significant between-group differences are highlighted in bold. Asterisks indicate significance of within group changes from baseline to time point.

p≤0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Psychosocial and Behavioral Outcomes

Across groups, significant improvements from baseline to week 52 were observed for several outcomes, including depression, body image, and quality of life (see Table 4). No differences were found between groups in improvements on any psychosocial outcome (see Supplementary Table 1 for additional outcomes). Consistent with week 12 and 26 results (4), BWL+BIAS participants reported significantly greater reductions in hunger from baseline to week 52 than did BWL participants. No other behavioral outcomes differed by group.

Table 4.

Estimated mean change (± standard error) in psychosocial and behavioral outcomes from baseline to Weeks 26 and 52, and from Weeks 26 to 52

| Variable | BWL+BIAS | BWL | Mean Difference | p |

d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | |||||

| Week 26 | −2.9±0.8*** | −2.9±0.8*** | −0.03±1.1 | 0.98 | 0.01 |

| Week 52 | −2.9±0.9*** | −2.4±0.9** | −0.5±1.2 | 0.70 | 0.08 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.0±0.9 | 0.5±0.9 | −0.5±1.2 | 0.69 | 0.08 |

| GAD-7+ | |||||

| Week 26 | −1.6±0.8** | −0.8±0.8 | −0.8±1.2 | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| Week 52 | −1.5±0.9** | −0.3±0.9 | −1.2±1.2 | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.3±0.8 | 0.3±0.8 | −0.6±1.1 | 0.71 | 0.09 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | |||||

| Week 26 | −3.9±1.2** | −1.0±1.2 | −2.9±1.7 | 0.10 | 0.32 |

| Week 52 | −2.4±1.3 | −0.1±1.2 | −2.3±1.8 | 0.20 | 0.22 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.5±1.1 | 0.9±1.1 | 0.6±1.6 | 0.72 | 0.06 |

| Body Appreciation Scale | |||||

| Week 26 | 0.8±0.1*** | 0.5±0.1*** | 0.3±0.2 | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| Week 52 | 0.8±0.1*** | 0.4±0.1** | 0.4±0.2 | 0.07 | 0.36 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.0±0.1 | −0.1±0.1 | 0.1±0.1 | 0.51 | 0.18 |

| IWQOL-Lite Total | |||||

| Week 26 | 12.5±2.1*** | 14.1±2.1*** | −1.7±3.0 | 0.58 | 0.13 |

| Week 52 | 14.3±2.5*** | 13.4±2.5*** | 0.9±3.5 | 0.81 | 0.05 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.8±1.9 | −0.7±1.9 | 2.5±2.8 | 0.37 | 0.24 |

| Public Distress Subscale | |||||

| Week 26 | 9.9±2.6*** | 11.2±2.6*** | −1.3±3.6 | 0.72 | 0.07 |

| Week 52 | 12.6±2.7*** | 7.6±2.7** | 5.0±3.8 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 2.8±2.3 | −3.6±2.2 | 6.3±3.2 | 0.049 | 0.47 |

| WEL-SF | |||||

| Week 26 | 12.0±3.1*** | 8.9±3.1** | 3.1±4.4 | 0.49 | 0.14 |

| Week 52 | 8.3±3.4* | 1.0±3.4 | 7.3±4.9 | 0.14 | 0.32 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −3.7±3.0 | −7.9±3.0* | 4.2±4.3 | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| SEE | |||||

| Week 26 | 5.8±4.6 | −6.3±4.5 | 12.1±6.5 | 0.06 | 0.35 |

| Week 52 | −3.1±4.9 | −6.8±4.8 | 3.7±6.9 | 0.59 | 0.11 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −8.9±4.4* | −0.4±4.4 | −8.5±6.2 | 0.17 | 0.31 |

| Eating Inventory | |||||

| Dietary Restraint | |||||

| Week 26 | 6.4±0.8*** | 5.2±0.8*** | 1.2±1.1 | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| Week 52 | 3.5±0.9*** | 3.2±0.9*** | 0.3±1.3 | 0.82 | 0.05 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −2.9±0.9*** | −2.0±0.9* | −0.9±1.2 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Disinhibition | |||||

| Week 26 | −3.0±0.6*** | −2.2±0.6*** | −0.8±0.8 | 0.34 | 0.20 |

| Week 52 | −1.8±0.5** | −1.2±0.6* | −0.6±0.8 | 0.45 | 0.13 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.1±0.6* | 1.0±0.6 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.82 | 0.04 |

| Hunger | |||||

| Week 26 | −3.9±0.5*** | −1.4±0.5* | −2.5±0.8 | 0.001 | 0.66 |

| Week 52 | −2.9±0.6*** | −0.7±0.6 | −2.2±0.8 | 0.007 | 0.61 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.0±0.5 | 0.7±0.5 | 0.3±0.7 | 0.69 | 0.09 |

| Self-Reported Weighing | |||||

| Week 26 | 1.0±0.2*** | 0.6±0.2** | 0.4±0.3 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| Week 52 | 0.9±0.2*** | 0.5±0.2* | 0.4±0.3 | 0.23 | 0.24 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.1±0.2 | −0.1±0.2 | 0.0±0.3 | 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Track Food/Drink+ | |||||

| Week 26 | 1.6±0.3*** | 1.6±0.3*** | 0.1±0.4 | 0.90 | 0.03 |

| Week 52 | 0.8±0.2** | 0.7±0.2 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.48 | 0.16 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.8±0.3* | −1.2±0.3*** | 0.4±0.5 | 0.39 | 0.09 |

| Track Calories+ | |||||

| Week 26 | 1.7±0.3*** | 1.4±0.3*** | 0.3±0.5 | 0.36 | 0.18 |

| Week 52 | 1.2±0.3*** | 1.3±0.3*** | −0.2±0.4 | 0.89 | 0.03 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.5±0.3 | −0.3±0.3 | −0.2±0.4 | 0.44 | 0.18 |

| Track Activity+ | |||||

| Week 26 | 1.3±0.3*** | 0.9±0.3** | 0.5±0.4 | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| Week 52 | 0.8±0.3** | 0.3±0.3 | 0.4±0.5 | 0.30 | 0.21 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.4±0.4 | −0.7±0.4 | 0.3±0.5 | 0.96 | 0.01 |

Note. Week 26 values from the original report are presented. PHQ-9=Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7=Generalized Anxiety Disorder; PSS=Perceived Stress Scale; IWQOL-Lite=Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite; SEE=Self-Efficacy to Exercise Scale; WEL-SF=Weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire – Short Form.

GAD-7 and Track Food/Drink and Activity scores underwent logarithmic transformation to fit assumptions of normality, and Track Calories scores were transformed with the square root; statistics for these variables are from linear mixed models, and raw change values are shown. Significant between-group differences are highlighted in bold. Asterisks indicate significance of within group changes from baseline to time point.

p≤0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Weight Loss and CVD Risk Factors

At week 52, BWL+BIAS and BWL participants lost a mean of 3.1±1.0% and 4.0±1.0% of baseline weight, respectively, with no significant between-group differences (see Table 5). Changes in CVD risk factors also did not differ between groups. Percent weight change did not correlate significantly with changes in any measure of WBI from baseline to week 52.

Table 5.

Estimated mean change (± standard error) in weight and cardiovascular risk factors from baseline to Weeks 26 and 52, and from Weeks 26 to 52

| Variable | BWL+BIAS | BWL | Mean Difference | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Weight Change | |||||

| Week 26 | −4.5±1.0*** | −5.9±1.0*** | 1.4±1.4 | 0.31 | 0.26 |

| Week 52 | −3.1±1.0** | −4.0±1.0*** | 0.9±1.5 | 0.53 | 0.14 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 1.4±0.6* | 1.9±0.6** | −0.5±0.9 | 0.59 | 0.09 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | |||||

| Week 26 | −4.3±0.9*** | −5.1±0.9*** | 0.8±1.3 | 0.54 | 0.15 |

| Week 52 | −4.4±1.0*** | −4.4±1.0*** | 0.0±1.5 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −0.1±0.9 | 0.7±0.9 | −0.8±1.2 | 0.54 | 0.16 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg)+ | |||||

| Week 26 | −2.6±1.6 | −2.4±1.6 | −0.2±2.2 | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| Week 52 | −5.7±2.5* | −4.3±2.5 | −1.4±3.6 | 0.71 | 0.09 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | −3.1±2.5 | −1.9±2.5 | −1.2±3.5 | 0.73 | 0.09 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg)+ | |||||

| Week 26 | −1.4±1.2 | −2.1±1.1 | 0.7±1.6 | 0.67 | 0.08 |

| Week 52 | −1.1±1.3 | −1.8±1.3 | 0.7±1.9 | 0.72 | 0.08 |

| Week 26 to Week 52 | 0.4±1.3 | 0.3±1.3 | 0.0±1.9 | 0.98 | 0.01 |

Note. Week 26 values from the original report are presented. Percent weight change was calculated from week 1 weights; all other values were measured at screening.

Blood pressure analyses control for whether or not participant took blood pressure medication at any time during the study. Asterisks indicate significance of within group changes from baseline to time point.

p≤0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Changes from Week 26 to Week 52

Participants in the BWL+BIAS group reported significantly greater improvements on the Public Distress subscale of the IWQOL-Lite from week 26 to 52 than did participants in the BWL group (2.8±2.3 vs. −3.6±2.2, p=0.049; Table 4). The IWQOL-Lite Sexual Life subscale showed a similar between-group difference in change in follow-up scores (see Supplementary Table 1). No other between-group differences emerged for changes between weeks 26 and 52. Across groups, significant worsening was observed from weeks 26 to 52 in outcomes such as percent weight loss, dietary restraint, and self-reported tracking of food.

From week 26 to week 52, 55.6% of participants who completed the assessment regained at least 1 percentage point of lost weight. Participants who gained 1 percentage point or more of their weight, compared to those who did not, had significantly greater increases in WBIS scores from week 26 to week 52 (0.3±0.8 vs. −0.2±0.9, p=0.03).

Safety and Treatment Acceptability

No AEs affected 5% or more of participants in either group. No SAEs were reported. Overall treatment acceptability ratings at week 52 did not differ between groups (BWL+BIAS 6.5±0.6, BWL 6.2±0.9, p=0.14). No differences were found between groups for reported learning of behavioral weight loss skills or healthy recipes (means all above 5, p values >0.10). Similarly, between groups, participants did not report differences in learning new things (6.6±0.7 vs. 6.3±1.1, p=0.23) or endorsing that the program helped with their weight management goals (5.9±1.5 vs. 5.5±1.5, p=0.37). However, participants in the BWL+BIAS group reported significantly greater changes in their attitudes about themselves as a result of the program (6.2±0.9 vs. 5.0±1.4, p=0.001). In addition, the BWL+BIAS group reported significantly greater acquisition and use of skills from the Weight BIAS program than did the BWL group (see Table 6). Of note, participants between groups did not differ in ratings of learning or use of skills to build confidence in the ability to stick with healthy eating and activity goals.

Table 6.

Mean ± Standard Deviation of Weight BIAS Skills Acquisition and Use Ratings (N=54)

| Skills Acquisition | BWL+BIAS | BWL | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenge myths and stereotypes about obesity | 6.2±1.4 | 4.6±2.0 | 0.001 | 0.95 |

| Identify biological and environmental factors that contribute to obesity | 5.8±1.0 | 5.0±1.9 | 0.06 | 0.52 |

| Identify relationship between thoughts, feelings, and weight management behaviors | 6.3±0.9 | 5.5±1.6 | 0.04 | 0.57 |

| Reduce negative thoughts and critical self-talk about my weight | 6.1±1.1 | 4.8±1.6 | 0.001 | 0.93 |

| Reframe negative situations and thoughts related to my weight in a more positive or accurate way | 6.1±1.0 | 4.9±1.7 | 0.002 | 0.87 |

| Ask others to change their behavior related to my weight (for example, to stop making negative comments about my weight) |

5.7±1.5 | 4.4±2.0 | 0.01 | 0.72 |

| Feel empowered to stand up for myself if someone treats me poorly because of my weight | 6.2±0.8 | 4.7±2.1 | 0.001 | 0.95 |

| Increase confidence in my ability to achieve or stick with my eating goals | 5.9±1.2 | 5.3±1.6 | 0.16 | 0.39 |

| Increase confidence in my ability to achieve or stick with my activity goals | 5.7±1.2 | 5.2±1.7 | 0.20 | 0.36 |

| Increase self-compassion concerning my weight | 6.1±1.1 | 5.2±1.7 | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| Increase self and body acceptance | 5.8±1.3 | 4.9±1.6 | 0.02 | 0.65 |

| Decrease self-hatred or contempt concerning my weight | 6.2±1.2 | 5.0±1.5 | 0.002 | 0.88 |

| Skills Use | BWL+BIAS | BWL | p | d |

| Challenge myths and stereotypes about obesity | 4.0±1.1 | 2.8±1.0 | <0.001 | 1.10 |

| Identify biological and environmental factors that contribute to obesity | 4.0±0.8 | 3.2±1.2 | 0.007 | 0.76 |

| Identify relationship between thoughts, feelings, and weight management behaviors | 4.2±1.0 | 3.6±1.4 | 0.06 | 0.52 |

| Reduce negative thoughts and critical self-talk about my weight | 4.3±0.8 | 3.1±1.3 | <0.001 | 1.16 |

| Reframe negative situations and thoughts related to my weight in a more positive or accurate way | 4.2±0.9 | 3.1±1.4 | 0.001 | 0.99 |

| Ask others to change their behavior related to my weight (for example, to stop making negative comments about my weight) |

3.3±1.3 | 2.4±1.2 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Feel empowered to stand up for myself if someone treats me poorly because of my weight | 4.2±1.0 | 2.9±1.5 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| Increase confidence in my ability to achieve or stick with my eating goals | 3.9±1.1 | 3.3±1.2 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| Increase confidence in my ability to achieve or stick with my activity goals | 3.8±1.2 | 3.3±1.2 | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Increase self-compassion concerning my weight | 4.2±1.0 | 3.3±1.2 | 0.007 | 0.76 |

| Increase self and body acceptance | 4.1±1.0 | 3.4±1.3 | 0.02 | 0.66 |

| Decrease self-hatred or contempt concerning my weight | 4.3±1.0 | 3.0±1.0 | <0.001 | 1.28 |

| Talk with others about negative societal attitudes toward and treatment of people with obesity | 4.0±1.2 | 2.3±1.2 | <0.001 | 1.34 |

Note. Learning of skills (acquisition) during the program was rated from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much so). Frequency of skill use post-treatment was rated from 1 (never) to 5 (frequently). Significant differences are highlighted in bold.

Discussion

The current study provides a 6-month non-intervention follow-up assessment of a psychological intervention that targeted WBI combined with, and in comparison to, BWL treatment alone. This is the first RCT to test such an intervention. Given the prevalence of weight regain following BWL (5), follow-up assessments are critical to determining the benefits of new treatment programs. Participants who received the stigma-reduction intervention reported retaining and using stigma-related skills from the program at week 52, as well as experiencing greater reductions in negative affect following instances of weight stigmatization compared to participants who received BWL alone. In addition, the BWL+BIAS group continued to show greater reductions, after treatment had ended, in public distress due to weight than did the BWL group. However, the primary outcome of WBI did not differ significantly between groups at week 52.

Several potential hypotheses may explain this lack of difference. First, participants in the BWL group showed greater decreases in WBIS scores than initially predicted based on previous studies (21,22). Engaging in a group-based program with built-in support from fellow participants and study staff may be particularly beneficial for individuals with obesity who struggle with low self-worth due to their weight. Qualitative responses from the treatment acceptability assessments suggested that BWL+BIAS participants reported feeling more self-appreciation and self-esteem as a result of the program, while BWL participants reported feeling less alone (see Supplementary Table 2). Both of these benefits could result in lower reports of WBI, depression, and other psychosocial outcomes, thus diminishing between-group differences.

Related to this point, the process of changing one’s eating and activity habits as part of a weight loss program may inherently challenge internalized stereotypes that participants are lazy or lack willpower, thus reducing WBI across groups. Weight loss was not correlated with changes in WBI. However, participants who regained 1 percentage point or more of their lost weight from weeks 26 to 52 reported significantly greater increases (i.e., worsening) in WBIS scores than participants who did not regain. The directionality of this relationship cannot be determined from the current study. Future research could further probe whether weight regain increases WBI or vice versa.

While this study provided a 6-month follow-up assessment of stigma-reduction intervention combined with BWL, 1 year or more of follow-up is needed to better understand the long-term effects of this combined therapy. This study was also limited by the short-term nature of the treatment. Future studies may test a longer intervention that provides a stronger dose of stigma reduction. The present trial was powered to detect medium effect sizes, and results may not generalize to individuals with low levels of WBI. Further clarification of clinically-significant cutoffs on the WBIS is also needed, which could enable more fine-grained examination of treatment responses stratified by mild, moderate, and severe WBI. Dissemination of this intervention to a larger patient sample (for example, through digital application) may help to clarify whether this intervention has significant, small effects for a wide range of patients on WBI, anxiety, body appreciation, self-efficacy, and other mental and physical health outcomes, as compared to BWL alone.

Conclusion

Six months after the conclusion of an RCT that tested the effects of a stigma-reduction program combined with standard BWL treatment, compared to BWL alone, no significant between-group differences were found for the primary outcome of WBI. This may be due, in part, to the unexpected magnitude of improvements on WBI measures in the BWL comparison group. A stronger dose of stigma-reduction treatment (i.e., more sessions over a longer period of time) may be needed to chip away at internalized, self-critical beliefs beyond the changes that may occur when patients improve their health behaviors, lose weight, and receive group support. Importantly, the Weight BIAS Program did not appear to detract from overall weight loss or acquisition of weight management skills. Results also showed significantly greater reported acquisition and use of stigma coping skills, and greater reductions in public distress and negative affect in response to weight-stigmatizing situations, in the BWL+BIAS compared to the BWL group. Further research is needed to determine whether these improvements in coping and distress may translate to clinically-meaningful benefits for mental and physical health in larger samples of adults with obesity who have experienced and internalized weight bias.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance.

What is already known about the subject?

Weight bias internalization (WBI), or weight self-stigma, is associated with impaired weight-related health.

The Weight Bias Internalization and Stigma (BIAS) program, combined with behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatment, reduced some aspects of weight self-stigma after 12 and 26 weeks, above and beyond the effects of BWL alone.

What are the new findings?

WBI improved across groups at week 52 but did not differ between the BWL+BIAS and BWL groups.

The BWL+BIAS group reported greater follow-up improvements in weight-related public distress, eating behaviors, and affective coping and skills use in response to weight stigma.

How might the results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

Future studies might test the effects of a stigma-reduction program in weight management for a longer duration and in a larger sample.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr. Ariana Chao for serving as the study’s Data and Safety Monitor. The study protocol and analysis plan are available on ClinicalTrials.gov. Deidentified data will be made available upon request.

Funding: This work was supported by WW (formerly Weight Watchers). RLP is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH (#K23HL140176). JST is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease of the NIH (#K23DK116935).

Disclosure: RLP discloses receiving grant funding for the current work from WW and serving as a consultant for WW and Novo Nordisk in the past 36 months. TAW discloses receiving grant funding for the current work from WW and serving on the advisory boards for WW and Novo Nordisk. JST discloses serving as a consultant for Novo Nordisk. RIB discloses serving on the advisory board for WW and receiving grant funding outside of the current work from Eisai.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identification: NCT03572218

References

- 1.Durso LE, Latner JD. Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. Obesity 2008;16:S80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes Rev 2018;19(8):1141–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearl RL, Hopkins CM, Berkowitz RI, Wadden TA. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for internalized weight stigma: A pilot study. Eat Weight Disord 2018;23(3):357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Bach C, et al. Effects of a cognitive-behavioral intervention targeting weight stigma: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82(11):2225–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Diabet Care 2002;25(12):2165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownell KD. The LEARN Program for Weight Management. 10th Edition ed. Dallas, Texas: American Health Publishing Company; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014;129:S102–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, et al. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity 2006;14(5):737–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lillis J, Luoma JB, Levin ME, Hayes SC. Measuring weight self-stigma: The Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire. Obesity 2010;18(5):971–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacon JG, Scheltema KE, Robinson BE. Fat phobia scale revisited: the short form. Int J Obes 2001;25:252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, Quinn DM. Weight stigma and health: The mediating role of coping responses. Health Psychol 2018;37(2):139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life. Obesity 2001;9(2):102–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic severity measures. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32(9):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. p. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow N. The Body Appreciation Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2005;2(3):285–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ames GE, Heckman MG, Grothe KB, Clark MW. Eating self-efficacy: Development of a short-form WEL. Eat Behav 2012;13:375–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnick B, Jenkins LS. Testing the reliabilty and validity of the Self-Efficacy for Exercise scale. Nurs Res 2000;49(3):154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29(1):71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearl RL, Wadden TA, Chao AM, Walsh O, Alamuddin N, Berkowitz RI, et al. Weight bias internalization and long-term weight loss in patients with obesity. Ann Behav Med 2019;53(8):782–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mensinger JL, Calogero RM, Tylka TL. Internalized weight stigma moderates eating behavior outcomes in women with high BMI participating in a healthy living program. Appetite 2016;102:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.