Abstract

Purpose

Dermal fibrosis is a disabling late toxicity of radiotherapy. Several lines of evidence suggest that overactive signaling via the Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta (PDGFR-β) and V-abl Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 (cAbl) may be etiologic factors in the development of radiation-induced fibrosis. We tested the hypothesis that imatinib, a clinically available inhibitor of PDGFR-β Mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (c-kit) and cAbl, would reduce the severity of dermal fibrosis in a murine model.

Materials and methods

The right hind legs of female C3H/HeN mice were exposed to 35 Gy of X-rays. Cohorts of mice were maintained on chow formulated with imatinib 0.5 mg/g or control chow for the duration of the experiment. Bilateral hind limb extension was measured serially to assess fibrotic contracture. Immunohistochemistry and biochemical assays were used to evaluate the levels of collagen and cytokines implicated in radiation-induced fibrosis.

Results

Imatinib treatment significantly reduced hind limb contracture and dermal thickness after irradiation. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated a substantial reduction in PDGFR-β phosphorylation. We also observed reduced Transforming Growth factor-β (TGF-β) and collagen expression in irradiated skin of imatinib-treated mice, suggesting that imatinib may suppress the fibrotic process by interrupting cross-talk between these pathways.

Conclusions

Taken together, these results support that imatinib may be a useful agent in the prevention and treatment of radiation-induced dermal fibrosis.

Keywords: Radiation, dermal, fibrosis, imatinib, Platelet-derived growth factor-receptor

Introduction

Localized external beam radiotherapy is an effective means to achieve control of solid tumors. Collateral injury of adjacent healthy tissues may result in toxicity and frequently limits the therapeutic dose of radiation that can be delivered (Wright and Coates 2006). The skin is a frequent site of acute radiation toxicity due to the radiosensitivity of the basal cell layer and dermal capillaries (Rodemann and Bamberg 1995). In the acute phase of radiation injury of the skin, erythema may be evident within hours of irradiation, and inflammation is observed in the ensuing days-to-weeks. Desquamation and ulceration are occasionally observed at higher delivered doses; however, with appropriate care, these acute events can be addressed symptomatically and generally resolve without exacerbation (Muller and Meineke 2010). In contrast, progressive fibrotic transformation of the dermis is a late adverse effect of radiation exposure that may evolve over a course of months to years following radiotherapy or accidental exposures (Brush et al. 2007). Limited range of motion, pain, and poor cosmesis are well-described adverse events attributed to radiation-induced fibrosis (RIF) of the skin. Furthermore, there appears to be no predictive association between the severity of acute toxicity and the late development of fibrosis. Few effective anti-fibrotic therapies are available to mitigate or reverse this process once initiated.

Histologically, RIF is characterized by hyperproliferation and myofibroblastic differentiation of dermal fibroblastic cells which secrete an abundance of collagen-rich extracellular matrix (Yarnold and Brotons 2010). These changes are thought to reflect perturbations of intercellular signal transduction mechanisms which regulate cell proliferation, apoptosis, immune response and extracellular matrix turnover (Herskind et al. 1998, Brush et al. 2007). Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is known to mediate several aspects of the fibrotic process (Martin et al. 2000). Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of this pathway has yielded promising results in animal and cell culture models (Flanders et al. 2003, Xavier et al. 2004, Liu et al. 2009), but have yet to translate to clinical application. Furthermore, Xavier et al. (2004) demonstrated that prolonged inhibition of TGF-β signaling with halofuginone largely abrogated the development of radiation-induced skin fibrosis in a murine model.

However, the refractory nature of RIF to TGF-β inhibition observed after withdrawal of another small-molecule TGF-β receptor inhibitor, SM16, suggests that persistent deviation of other signaling mechanisms upstream of this pathway may have a role in the development of dermal fibrosis (Anscher et al. 2008). Indeed, autoimmune activation of the Platelet-derived growth factor receptor Beta (PDGFR-β) has been shown to regulate TGF-β expression and modulate the cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis.

Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®, Novartis AG, Basel Switzerland) is an orally-bioavailable small-molecule inhibitor of the tyrosine kinases V-abl Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 (c-Abl), Mast/stem cell growth factor receptor (c-kit) and PDGFR-β that is used in the clinical management of several specific malignancies. Specific chromosomal rearrangements generating constitutively active variants of these tyrosine kinases are associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Imatinib treatment was found to reverse bone marrow fibrosis in Philadelphia chromosome positive chronic myelogenous leukemia, suggesting potential as an anti-fibrotic agent. Recent evidence has also shown imatinib to be an effective therapy in cases of systemic sclerosis where auto-immune activation of PDGFR-β is a contributing factor in the fibrotic process (Bibi and Gottlieb 2008). Imatinib has also been shown to reduce the severity of pulmonary RIF in small animal models (Li et al. 2009, Thomas et al. 2010). However, it is not clear that dermal and pulmonary fibrosis have identical molecular mechanisms given the differences in tissue physiology and cellular composition. Most conspicuously, the gas exchange function of the parenchyma elevates pulmonary stromal oxygen concentration to levels much greater than experienced by the skin. Additionally, whereas interstitial fibroblasts are relatively rare in the pulmonary alveolus and may evolve in pathology via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation, fibroblastic cells are the predominant constituent of the dermis. Furthermore, these barrier organs utilize a unique repertoire of immune cells specific to the different spectrum insults encountered. Taking the previously published data as proof of principle that imatinib may have utility as an anti-fibrotic agent in these very distinct contexts, it is reasoned that it may also have an application in addressing radiation-induced dermal fibrosis. The purpose of our present study was to evaluate the anti-fibrotic potential of imatinib in a small animal model of dermal RIF. Our hypothesis was that systemic imatinib treatment would suppress the contributions of PDGFR-β and TGF-β to the disease process and improve functional deficits commonly observed in a well-established murine model of dermal RIF.

Methods

Chemicals

Imatinib mesylate (Novartis, New York, NY, USA) was obtained from the Division of Veterinary Resources Pharmacy at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Animal studies

The animal studies completed in this report were institutionally approved and deemed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council. Female C3H/HeN mice, aged 8–10 weeks (National Cancer Institute Laboratory Animal Services Program, Frederick, MD, USA) were used for all studies. Irradiation of the right hind leg was performed with mice restrained in a custom-made, lead-lined lucite jig that allows for selective irradiation of the right limb without anesthesia. Beam collimation and lead shielding were used to protect the remainder of the body, including the contralateral limb which was used as an internal control. A single radiation dose of 35 Gy was delivered to the right hind leg with a X-RAD 320 X-ray irradiator (Precision X-Ray, North Branford, CT, USA) using 2.0 mm aluminum filtration (300 kilovolts peak) at a dose of 1.9 Gy/minute. The delivery of a single fraction of 35 Gy is well described in the literature as a means to efficiently and reproducibly generate fibrotic skin contracture in mice (Molin et al. 1981, Stone 1984, Flanders et al. 2002, Xavier et al. 2004). Immediately after irradiation, mice were removed from the jig and housed in a climate and light/dark controlled environment. All mice were allowed ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments were completed in duplicate in groups of at least 10 mice.

Imatinib treatment

Rodent chow was formulated by Bioserv (Frenchtown, NJ, USA) to contain 0.5 mg/g of imatinib. This route and formulation demonstrated efficacy as an anti-fibrotic in a murine model of radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis described by Li et al. (2009). Rodent chow with the otherwise identical composition, but without imatinib, was used as a control. Immediately after irradiation, mice in the imatinib treatment group received chow formulated with 0.5 mg imatinib per gram of chow and control mice received identical chow without imatinib. Mice were maintained on imatinib or control chow for the duration of the experiment. Chow consumption and body weight were monitored weekly.

Assessment of skin contracture

To measure the severity of contracture, we compared the difference in extension between the uniradiated and irradiated limbs as described by Stone (1984). Briefly, mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and positioned prone in a measuring apparatus to allow measurement of the irradiated and unirradiated hind leg. The hind limbs were then extended caudally using forceps, and the length of each extended limb was measured. Measurements were collected on the day of irradiation (time 0), and following the resolution of acute skin reaction at 90 and 150 days following irradiation. Differences in limb length were accepted as statistically significant when p ≤0.05 by Student’s paired t-test.

Tissue collection for assessment of dermal thickness, TGF-β expression and collagen accumulation

At 30, 60 and 122 days post-irradiation, full thickness samples of skin from the irradiated field or the analogous site on the contralateral limb were collected from three mice per treatment group, per time point. Tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 6 μm thickness and mounted on positively charged glass slides. Sections of skin from the 150 day time point were deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series to water. Sections were then incubated in Bouin’s picric-formalin and then stained using Masson’s trichrome with aniline blue as the collagen stain and Weigert’s iron hematoxylin as the nuclear counterstain. All histology reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) unless stated otherwise. Sections were dehydrated through graded alcohols to xylene, and coverslips were mounted with permount. Slides were examined on a Leica model DMRXA microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). Digital micrographs were captured at 10 × magnification using a Photometrics Sensys digital camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ, USA) and imported into IP Labs image analysis software package (Scanalytics, Inc., Fairfax, VA, U SA). Twelve images were obtained to encompass each of three serial sections from each mouse. The average vertical thickness of the dermis was measured using ImageJ v1.44i image processing software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Measurements were obtained at equally spaced intervals across each image. Values obtained were normalized to skin thickness of unirradiated skin in control chow fed mice. Statistically significant differences between control and irradiated skin were assessed using Student’s paired t-test, while differences between control and imatinib-treated mice were assessed using the non-paired t-test. Differences were accepted as significant when p≤ 0.05.

Tissue collection for assessment of TGF-β1 expression and collagen accumulation

At 30, 60 and 122 days post-irradiation, skin tissues were collected from the irradiated field or the analogous site on the contralateral limb from three mice per treatment group, snap frozen and stored at −8°C until assay. Subcutaneous fascia, musculature and adipose tissue were removed manually with aid of a dissecting microscope. For determination of total TGF-β1 levels, skin tissue was weighed and homogenized in radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing a cocktail of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (10 ml/g tissue, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Centrifugation was performed to remove insoluble debris, and the resulting supernatant was used to determine the concentration of total soluble TGF-β1 in the tissue using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Duoset # DY1679, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The concentration of total TGF-β1 was calculated by interpolation to a standard curve of known TGF-β1 concentrations and normalized by tissue weight. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. Difference between treatments was assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA; Statview 5.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and accepted as statistically significant at p≤ 0.05.

A colorimetric dye-binding assay (Walsh et al. 1992) was used to assess the accumulation of fibrillar collagen in skin samples collected as described above. Prior to assay, skin samples were weighed, minced and digested overnight in 0.5% pepsin/0.5M acetic acid at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Insoluble debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the resulting supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of 0.1% Sirius Red dye in saturated picric acid (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) to bind and precipitate fibrillar collagens. Collagen-dye complexes were pelleted by centrifugation, washed once with 0.5M acetic acid, and solubilized with 0.5M sodium hydroxide to release the bound dye. Absorbance of the released dye at 562 nm was read on a microplate reader, and converted to collagen equivalents by interpolation to a standard curve on known concentrations of rat type I collagen (Sigma), and normalized to tissue weight. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. Differences between treatments were assessed by ANOVA (Statview 5.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and accepted as statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series to water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in water for 5 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving for 10 min at full power and 10 min at 30% power in citrate buffer (pH 6.8). The ImmPRESS system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used with primary antibodies to TGF-β, phosphorylated c-Abl, platelet-derived growth factor-B (PDGF-B) and phosphorylated PDGFR-β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, following blocking with 2.5% normal horse serum, sections were incubated with the appropriate primary antibody at a dilution of 1:200 for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.0, and incubated for 30 min in the ImmPRESS reagent. After washing, immunoreactivity was visualized with diaminobenzidine histochemistry (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded alcohols to xylene, and coverslipped for microscopic assessment of immunoreactivity.

Results

Tolerance to therapy

Weekly assessments of control and imatinib-treated mice revealed no significant differences in consumption of chow or body weight between the groups (data not shown). Based on the amount of food consumed, imatinib-fed mice averaged 50.8 mg/kg/d of the drug during the study, well below the dose at which cardiotoxicity was reported by Kerkela et al. (2006). Mice were followed after irradiation for evidence of acute toxicity. Typically, three weeks following the delivery of 35 Gy to the hind leg, mice begin to develop alopecia in the irradiated field, followed by erythema and patchy desquamation in the irradiated field which resolves over the next of 3–4 weeks. There was no evidence of a difference in the onset, severity, or duration of acute skin reaction between groups of mice treated with imatinib chow or control chow (data not shown).

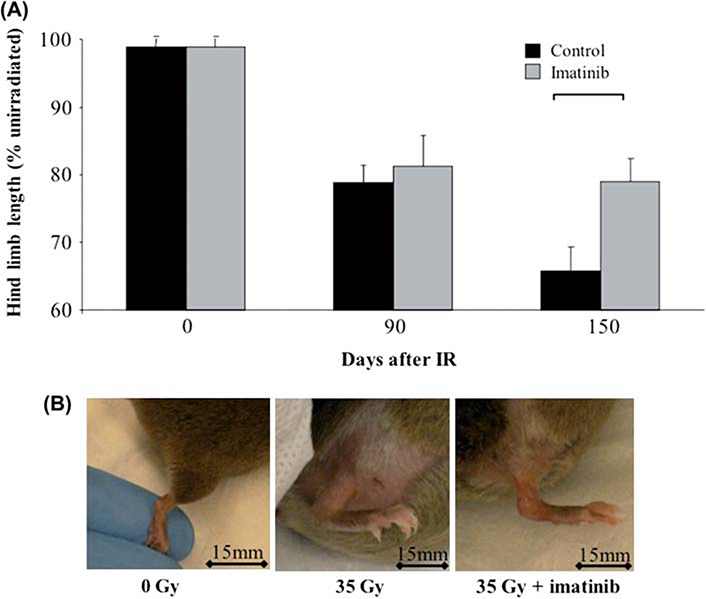

Radiation-induced hind limb contracture is reduced by imatinib

Dermal fibrosis with resultant contracture subsequent to radiotherapy is a crippling adverse event that was reproduced in our murine model. Hind limb length was measured in passive extension to assess the severity of radiation-induced soft tissue contracture at 90 and 150 days following irradiation. All mice showed progressive length reduction of the irradiated hind limb relative to the unirradiated contralateral limb (Figure 1, p <0.05). No significant differences were observed in the length of the non-irradiated limbs of control or imatinib-treated mice at any time point. In comparison of the irradiated limbs however, imatinib-treated mice showed significantly reduced skin contracture at 150 days (p ≤ 0.05) compared to control chow-fed mice.

Figure 1.

Radiation-induced hind limb contraction. (A) Extension of the irradiated hind limb was reduced compared to the contralateral unirradiated hind limb at all time points. A significant difference in the extension of the irradiated hind limb between imatinib and control chow treatment mice was found at 150 days. Error bars show SEM calculated from n = 8 mice at each time point, and bracket indicates significant difference p <0.05. (B) Representative photographs of the hind limb in non-irradiated, 35 Gy-irradiated and 35 Gy-irradiated, imatinib-treated mice at 150 days, illustrating improvement in limb extension, skin thickness, and edema with imatinib treatment. Bar shows 15 mm. This Figure is reproduced in color in the online version of International Journal of Radiation Biology.

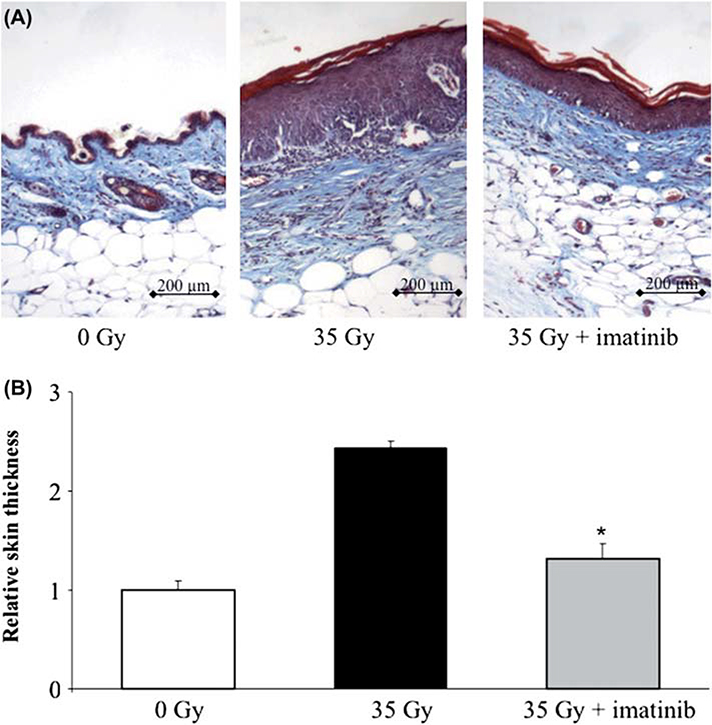

Radiation-induced alterations of skin morphology are improved by imatinib treatment

Range of motion limitations associated with radiotherapy derive from progressive fibrotic transformation of soft tissues (Flanders et al. 2002). This transformation is evident as an accumulation of a hypocellular extracellular matrix primarily composed of fibrillar collagens (Panizzon et al. 1986, 1988). In our experiments we collected bilateral full-thickness skin samples from three mice at 60, 90, 122 and 150 days following exposure to 35 Gy. Irradiated tissues from mice that were fed control chow showed progressive morphological changes characteristic of radiation injury, including epidermal hyperplasia, interface dermatitis, basal vacuolar damage, loss of follicles, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis (Figure 2A). Irradiated skin collected from imatinib-treated mice showed substantial improvement of these features, with the exception of similar levels of hyperkeratosis. Furthermore, dermal thickness was increased 2.5-fold after irradiation. Imatinib treatment was associated with a significant reduction in dermal thickness compared to control (p < 0.05) at 150 days post-irradiation. The prevention of dermal thickening after irradiation with imatinib treatment was not complete, as evidenced by a significant increase in dermal thickness in imatinib-treated radiated skin compared to unirradiated skin at 150 days.

Figure 2.

Imatinib reduces skin thickness after irradiation. (A) Representative images of sections of skin sampled at 150 days stained with Masson’s Trichrome technique (collagen = blue, muscle and epithelial layers = red). Irradiated sections demonstrate both marked thickening of the epidermis and dermis. (B) Relative skin thickness in mice receiving 35 Gy alone or 35 Gy and imatinib was increased compared to unirradiated controls. A significant reduction in skin thickness was observed in the skin of imatinib-treated mice exposed to 35 Gy compared to skin from mice that received 35 Gy and control chow. Measurements are mean of n = 3 mice per treatment and error bars show SEM; *indicates p < 0.001 compared to other treatments. This Figure is reproduced in color in the online version of International Journal of Radiation Biology.

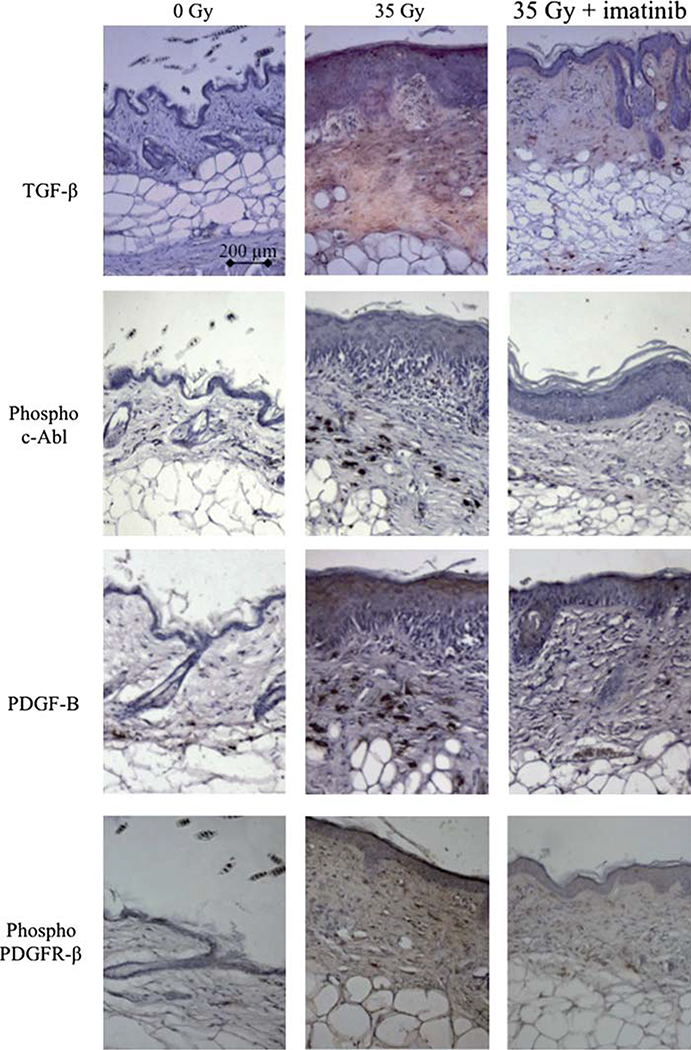

Imatinib treatment is associated with reduced PDGFR-β phosphorylation, TGF-β expression and collagen accumulation in irradiated tissues.

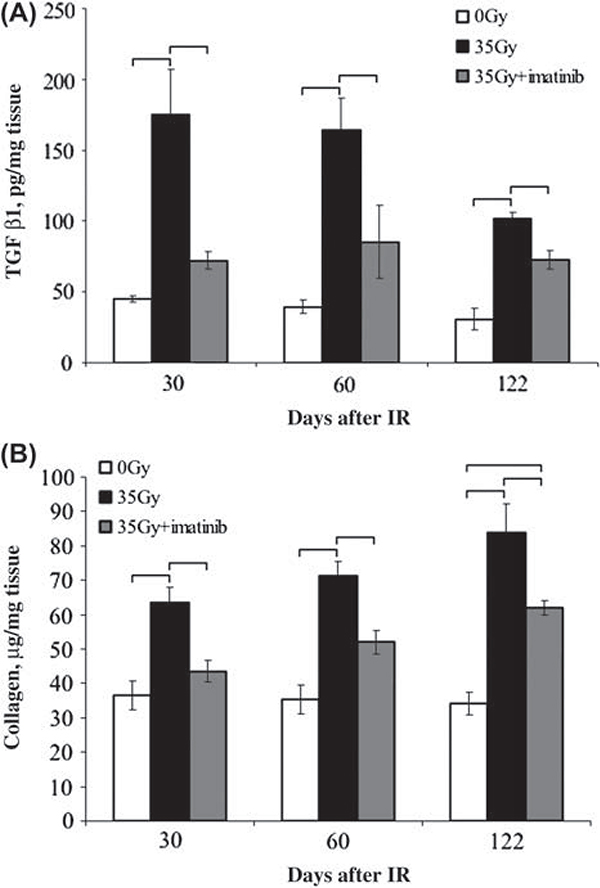

Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated an increase in PDGFR-β phosphorylation and TGF-β expression in irradiated skin compared to unirradiated skin. Substantially reduced PDGFR-β phosphorylation and TGF-β expression was observed in irradiated skin of imatinib-treated mice (Figure 3). The expression of PDGF-B and the phosphorylation of c-Abl followed a similar pattern. These findings were confirmed by ELISA of tissue homogenates (Figure 4). Imatinib treatment significantly reduced TGF-β1 levels in the irradiated skin (p ≤ 0.0128) in comparison to irradiated control tissues, and was only demonstrated to be significantly greater than the unirradiated controls at 122 days post irradiation. Imatinib treatment produced no significant change of TGF-β1 levels in unirradiated skin at any time point relative to skin collected from mice fed the control chow (data not shown, p ≥ 0.1022).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical evaluation of mouse skin. Skin from the hind limb of mice fed control chow or imatinib chow were exposed to 35 Gy irradiation. At 150 days, samples were obtained for immunohistochemical evaluation. TGF-β was present in the dermis of mice receiving 35 Gy but was markedly reduced with imatinib treatment. Nests of fibrosis in the subcutaneous fat layer were also noted to exhibit expression of TGF-β Expression of phosphorylated c-Abl, PDGF-B and phosphorylated PDGFR-β followed a similar pattern. Sections were photographed at 10 × magnification; bar shows 200 μm. This Figure is reproduced in color in the online version of International Journal of Radiation Biology.

Figure 4.

Assessment of TGF-β1 and fibrillar collagen in mouse skin. Full-thickness samples of skin were collected from the irradiated and contralateral hind limb of mice at 30, 60 and 122 days post irradiation. (A) A sandwich ELISA was used to determine TGF-β1 levels from skin homogenized in RIPA buffer. (B) Collagen content in skin samples was determined by a Sirius red dye-binding assay following digestion with pepsin and acetic acid. For both assays, sample values were interpolated from a standard curve, and normalized to tissue weight. Data shown are average normalized value ± standard error of n = 3 samples per time point. Brackets indicate statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between treatment groups as determined by ANOVA.

Imatinib treatment significantly reduced levels of acid-pepsin soluble collagen levels in the irradiated skin samples (p ≤ 0.0129) when compared to control chow fed mice. Significantly increased levels of acid-pepsin soluble collagen were observed in irradiated tissues (p ≤ 0.0039) of control mice, relative to the contralateral side. Despite this improvement, the concentration of collagen in irradiated skin collected was significantly greater than the contralateral unirradiated side in both control (p =0.0039) and imatinib fed groups (p = 0.0129) at the 60 and 122 day time points. Differences in collagen concentration of the unirradiated skin collected from control and imatinib-treated mice were observed only at the 60 day time point (p = 0.0247, data not shown).

Discussion

Reduced range of motion, pain and poor cosmesis due to radiation-induced fibrosis pose significant quality-of-life concerns for cancer survivors who have received high dose localized radiotherapy as part of their treatment. Accidental exposures to high cutaneous doses have also been associated with fibrotic complications. Although a high radiation dose, prior surgeries in the treated area, and genetic predisposition may increase the likelihood of developing dermal RIF, it is currently impossible to accurately predict who will develop this disabling side-effect. Therefore, strategies which reduce or abrogate the development and progression of fibrosis are needed. Radiation-induced derangement of paracrine signaling mechanisms, including the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and TGF-β pathways are thought to drive the process of fibrotic transformation. Therefore, it is anticipated that pharmacological compounds targeting these pathways would provide a means to suppress or reverse fibrosis in irradiated tissues. We hypothesized that imatinib treatment would provide a significant mitigation of radiation-induced dermal fibrosis in a murine model.

Aberrant activation of PDGFR signaling has been described as an etiologic component of several fibrotic processes including RIF (Reviewed by Wynn 2008). Abdollahi et al. (2005) have demonstrated that radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis is mediated in part by increased PDGF expression resulting in increased phosphorylation of PDG-FR-β. Subsequent studies by this group showed that imatinib treatment significantly improved the pulmonary morbidity associated with thoracic irradiation in a murine model (Li et al. 2009). Furthermore, they demonstrated in vitro that inhibition of PDGF signaling with imatinib disrupted a reciprocal interaction between irradiated vascular endothelial cells and non-irradiated myofibroblastic cells that promoted survival of the former and proliferation of the latter (Li et al. 2006). While the studies by this group did not comment specifically on the cellular source of PDGFR activating ligands, others as reviewed by Bonner (2004) have posited that alveolar macrophages are the primary source of platelet-derived growth factor-A (PDGF-A), while PDGF-B ligand is produced by the myofibroblast in radiation-injured lung tissue. Taken together, these studies highlight the complex paracrine nature of PDGF signaling in pulmonary fibrosis.

While a similar signaling environment has yet to be demonstrated specifically in radiation-induced dermal fibrosis, several lines of evidence drawn from other model systems suggest that imatinib may have utility in this context. Distler et al. (2007) examined the utility of imatinib in a murine model of bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis. Significant reduction of skin thickness, collagen deposition and myofibroblast number were observed in imatinib-treated animals. Persistent autoimmune activation of PDGFR-β has been suggested as an etiologic factor in certain presentations of systemic sclerosis observed in the clinic (Gabrielli et al. 2007); however, it is unclear whether this is a causative or associative finding (Classen et al. 2009). Several investigators have recently demonstrated efficacy of imatinib as an anti-fibrotic therapy in pre-clinical animal models of systemic sclerosis (Bibi and Gottlieb 2008, Akhmetshina et al. 2009) and early reports from human clinical trials are promising (Kay and High 2008). Other lines of evidence suggest that imatinib may disrupt fibrotic transformation and progression by suppressing signaling cascades mediated by c-Abl (Bhattacharyya et al. 2009), or by stimulating expression of mir29A (Maurer et al. 2010), in each case suppressing extracellular matrix deposition and fibroblast proliferation.

Our study sought to examine the efficacy of imatinib in the context of radiation-induced dermal fibrosis subsequent to a single, high-dose radiation exposure. This experimental design is a departure from the common clinical practice of delivering a series of fractionated exposures to achieve a cumulative radiation dose. Nonetheless, this model is well established and accepted as a means to model cutaneous radiation injury and approximates the severity of injury that could be expected from an accidental single exposure or that accumulated upon completion of a standard therapeutic regimen (Molin et al. 1981, Stone 1984, Flanders et al. 2002, Xavier et al. 2004). Furthermore, it should be noted that delivery of large fractional doses of radiation are becoming more widespread clinically due to the proliferation of stereotactic and intraoperative procedures in clinical practice.

To evaluate the effects of imatinib in this model, we assessed range of motion and skin thickness as clinically relevant indicators of fibrosis in mice, and observed a significant improvement of these conditions in mice that were fed chow containing imatinib. These improvements were associated with decreased levels of phosphorylated PDGFR-β and expression of TGF-β in imatinib-treated mice. While these results were encouraging, the improvements observed were insufficient to completely reverse the evolution and progression of fibrosis. This suggests that other parallel signaling mechanisms may be involved in this disease process, and holds open the possibility that combining imatinib with pharmacologic agents targeting other pathways implicated in fibrosis may provide greater benefit than either agent alone.

Interestingly, treatment with imitinib not only reduced the activation of PDGFR-β and c-Abl, two known targets of imatinib, but also decreased the levels of TGF-β in irradiated skin. It is likely that interactions of TGF-β and PDGF signaling play an important role in RIF as the TGF-β and PDGF pathways appear to interact in a number of ways at the cellular and tissue level. For example, TGF-β receptor activation results in downstream activation of Smad2 and Smad3, which has been shown to interact with the PDGF-B promoter region in glioma cells in response to TGF-β. This places the TGF-β pathway as an upstream regulator of PDGF-B production (Bruna et al. 2007). Conversely, platelet-derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFR-α) activation via the homodimer platelet-derived growth factor-AA (PDGF-AA) or heterodimer platelet-derived growth factor-AB (PDGF-AB) stimulates expression of TGF-β receptors in dermal fibroblasts (Czuwara-Ladykowska et al. 2001). Similar effects have been seen in vascular smooth muscle cells with platelet-derived growth factor-BB homodimer (PDGF-BB) (Pan et al. 2007). This reciprocal activation may reflect and result in cooperation of the two pathways after ionizing radiation, with one pathway (PDGF) acting to stimulate proliferation of mesenchymal cells and the other (TGF-β) acting to stimulate the production of extracellular matrix, with each stimulating signaling through the other pathway.

At the tissue level, evidence suggests that cooperation of TGF-β and PDGF signaling is critical to develop robust fibrosis. Yoshida et al. (1995) evaluated the results of overexpression of TGF-β or PDGF-B in lungs of mice via adenoviral gene transfer. PDGF-B over-expression alone resulted in mild interstitial fibrosis while over-expression of TGF-β resulted in PDGF-B expression and a more robust interstitial fibrosis with a greater component of mesenchymal cell proliferation. Other evidence supports that PDGF-B plays a role in mesenchymal cell proliferation and collagen deposition but that these effects are transient in the absence of TGF-β (Yi et al. 1996, Bonner 2004). Data from a variety of studies suggest that PDGF plays a role in expanding the number of matrix producing cells while TGF-β plays a greater role in matrix production.

In this model of dermal fibrosis, it appears that deranged signaling through PDGFR-β is capable by itself of inducing TGF-β, thus further stimulating fibrosis. Previously, Xavier et al. (2004) demonstrated robust anti-fibrotic activity of halofuginone, demonstrating that TGF-β is a key mediator of fibrosis in this model system. Here, we found that inhibiting PDGFR-β with imatinib was sufficient to decrease TGF-β expression, and may provide a mechanism for indirectly inhibiting TGF-β signaling in irradiated skin, thus avoiding the worrisome clinical toxicities observed with direct inhibition of TGF-β (Garber 2009). It is possible that incomplete inhibition of TGF-β signaling with imatinib led to only partial mitigation of fibrosis, suggesting combinatiorial approaches may have merit. In our model, continued administration of imatinib resulted in sustained PDGF-Rβ inhibition, and was able to partially mitigate fibrosis. Whether withdrawal of imatinib would result in rebound of both PDGF and TGF-β signaling, as shown with the TGF-β receptor inhibitor SM16 (Anscher et al. 2008), resulting in refractory fibrosis is unknown at this time.

Of particular interest for the clinical development of PDFGR inhibitors as mitigators of radiation injury, imatinib has been shown to increase the cytotoxicity of irradiation in tumors of diverse histologies (Russell et al. 2003, Choudhury et al. 2009, Chung et al. 2009, Ranza et al. 2009) suggesting concurrent or early post-treatment therapy would not interfere with the anti-tumor efficacy of radiotherapy. This is of particular appeal, as an early intervention strategy may be superior to delayed initiation of therapy for the treatment of radiation fibrosis. These data are the basis of a clinical trial in development that will assess the ability of PDGFR-β inhibition to mitigate RIF in the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Thus we conclude that imatinib treatment in this model system can inhibit radiation-induced dermal fibrosis, but has no effect on the severity or duration of radiation dermatitis. Future studies will focus on the interplay between signaling pathways inhibited by imatinib and TGF-β.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Abdollahi A, Li M, Ping G, Plathow C, Domhan S, Kiessling F, Lee LB, McMahon G, Grone HJ, Lipson KE. 2005. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor signaling attenuates pulmonary fibrosis. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 201:925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmetshina A, Venalis P, Dees C, Busch N, Zwerina J, Schett G, Distler O, Distler JH. 2009. Treatment with imatinib prevents fibrosis in different preclinical models of systemic sclerosis and induces regression of established fibrosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 60:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anscher MS, Thrasher B, Zgonjanin L, Rabbani ZN, Corbley MJ, Fu K, Sun L, Lee WC, Ling LE, Vujaskovic Z. 2008. Small molecular inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta protects against development of radiation-induced lung injury. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 71:829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S, Ishida W, Wu M, Wilkes M, Mori Y, Hinchcliff M, Leof E, Varga J. 2009. A non-Smad mechanism of fibroblast activation by transforming growth factor-beta via c-Abl and Egr-1: Selective modulation by imatinib mesylate. Oncogene 28:1285–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi Y, Gottlieb AB. 2008. A potential role for imatinib and other small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of systemic and localized sclerosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 59:654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JC. 2004. Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 15:255–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruna A, Darken RS, Rojo F, Ocana A, Penuelas S, Arias A, Paris R, Tortosa A, Mora J, Baselga J. 2007. High TGFbeta-Smad activity confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and promotes cell proliferation depending on the methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell 11:147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brush J, Lipnick SL, Phillips T, Sitko J, McDonald JT, McBride WH. 2007. Molecular mechanisms of late normal tissue injury. Seminars in Radiation Oncology 17:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury A, Zhao H, Jalali F, Al Rashid S, Ran J, Supiot S, Kiltie AE, Bristow RG. 2009. Targeting homologous recombination using imatinib results in enhanced tumor cell chemosensitivity and radiosensitivity. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 8:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung L, Fiorentino DF, Benbarak MJ, Adler AS, Mariano MM, Paniagua RT, Milano A, Connolly MK, Ratiner BD, Wiskocil RL. 2009. Molecular framework for response to imatinib mesylate in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 60:584–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen JF, Henrohn D, Rorsman F, Lennartsson J, Lauwerys BR, Wikstrom G, Rorsman C, Lenglez S, Franck-Larsson K, Tomasi JP. 2009. Lack of evidence of stimulatory autoantibodies to platelet-derived growth factor receptor in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 60:1137–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czuwara-Ladykowska J, Gore EA, Shegogue DA, Smith EA, Trojanowska M. 2001. Differential regulation of transforming growth factor-beta receptors type I and II by platelet-derived growth factor in human dermal fibroblasts. The British Journal of Dermatology 145:569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distler JH, Jungel A, Huber LC, Schulze-Horsel U, Zwerina J, Gay RE, Michel BA, Hauser T, Schett G, Gay S. 2007. Imatinib mesylate reduces production of extracellular matrix and prevents development of experimental dermal fibrosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 56:311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Sullivan CD, Fujii M, Sowers A, Anzano MA, Arabshahi A, Major C, Deng C, Russo A, Mitchell JB. 2002. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against cutaneous injury induced by ionizing radiation. The American Journal of Pathology 160:1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, Major CD, Arabshahi A, Aburime EE, Okada MH, Fujii M, Blalock TD, Schultz GS, Sowers A, Anzano MA. 2003. Interference with transforming growth factor-beta/ Smad3 signaling results in accelerated healing of wounds in previously irradiated skin. The American Journal of Pathology 163:2247–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielli A, Svegliati S, Moroncini G, Luchetti M, Tonnini C, Avvedimento EV. 2007. Stimulatory autoantibodies to the PDGF receptor: A link to fibrosis in scleroderma and a pathway for novel therapeutic targets. Autoimmunity Reviews 7:121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber K 2009. Companies waver in efforts to target transforming growth factor beta in cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 101:1664–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskind C, Bamberg M, Rodemann HP. 1998. The role of cytokines in the development of normal-tissue reactions after radiotherapy. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 174(Suppl. 3):12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay J, High WA. 2008. Imatinib mesylate treatment of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 58:2543–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkela R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, Walters B, Shevtsov S, Pesant S, Clubb FJ. 2006. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nature Medicine 12:908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Abdollahi A, Grone HJ, Lipson KE, Belka C, Huber PE. 2009. Late treatment with imatinib mesylate ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis in a mouse model. Radiation Oncology 4:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Ping G, Plathow C, Trinh T, Lipson KE, Hauser K, Krempien R, Debus J, Abdollahi A, Huber PE. 2006. Small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor signaling (SU9518) modifies radiation response in fibroblasts and endothelial cells. BMC Cancer 6:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Kudo K, Abe Y, Hu DL, Kijima H, Nakane A, Ono K. 2009. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta, hypoxia-inducible factor-lalpha and vascular endothelial growth factor reduced late rectal injury induced by irradiation. Journal of Radiation Research (Tokyo) 50:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Lefaix J, Delanian S. 2000. TGF-betal and radiation fibrosis: A master switch and a specific therapeutic target? International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 47:277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer B, Stanczyk J, Jungel A, Akhmetshina A, Trenkmann M, Brock M, Kowal-Bielecka O, Gay RE, Michel BA, Distler JH. 2010. MicroRNA-29, a key regulator of collagen expression in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 62:1733–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molin J, Sogaard PE, Overgaard J. 1981. Experimental studies on the radiation-modifying effect of bleomycin in malignant and normal mouse tissue in vivo. Cancer Treatment Reports 65:583–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K, Meineke V. 2010. Advances in the management of localized radiation injuries. Health Physics 98:843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Yang J, Lu F, Xu D, Zhou L, Shi A, Cao K. 2007. Platelet-derived growth factor BB modulates PCNA protein synthesis partially through the transforming growth factor beta signalling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochemistry and Cell Biology (Biochimieet biologie cellulaire) 85:606–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzon RG, Malkinson FD, Hanson WR, Schwartz DE. 1986. A one-year comparative study of post-irradiation collagen content and microscopic fibrosis in mouse skin. British Journal of Radiology 19:54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzon RG, Hanson WR, Schwartz DE, Malkinson FD. 1988. Ionizing radiation induces early, sustained increases in collagen biosynthesis: A 48-week study in mouse skin and skin fibroblast cultures. Radiation Research 116:145–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranza E, Bertolotti A, Facoetti A, Mariotti L, Pasi F, Ottolenghi A, Nano R. 2009. Influence of imatinib mesylate on radiosensitivity of astrocytoma cells. Anticancer Research 29:4575–4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodemann HP, Bamberg M. 1995. Cellular basis of radiation-induced fibrosis. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology 35:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JS, Brady K, Burgan WE, Cerra MA, Oswald KA, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ. 2003. Gleevec-mediated inhibition of Rad51 expression and enhancement of tumor cell radiosensitivity. Cancer Research 63 : 7377–7383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone HB. 1984. Leg contracture in mice: An assay of normal tissue response. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology and Physics 10:1053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Fox J, Haston CK. 2010. Imatinib therapy reduces radiation-induced pulmonary mast cell influx and delays lung disease in the mouse. International Journal of Radiation Biology 86:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BJ, Thornton SC, Penny R, Breit SN. 1992. Microplate reader-based quantitation of collagens. Analytical Biochemistry 203:187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EG, Coates PJ. 2006. Untargeted effects of ionizing radiation: Implications for radiation pathology. Mutation Research 597: 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA. 2008. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. The Journal of Pathology 214:199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier S, Piek E, Fujii M, Javelaud D, Mauviel A, Flanders KC, Samuni AM, Felici A, Reiss M, Yarkoni S. 2004. Amelioration of radiation-induced fibrosis: Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling by halofuginone. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279:15167–15176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnold J, Brotons MC. 2010. Pathogenetic mechanisms in radiation fibrosis. Radiotherapy and Oncology 97:149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi ES, Bedoya A, Lee H, Chin E, Saunders W, Kim SJ, Danielpour D, Remick DG, Yin S, Ulich TR. 1996. Radiation-induced lung injury in vivo: Expression of transforming growth factor-beta precedes fibrosis. Inflammation 20:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Sakuma J, Hayashi S, Abe K, Saito I, Harada S, Sakatani M, Yamamoto S, Matsumoto N, Kaneda Y. 1995. A histologically distinctive interstitial pneumonia induced by overexpression of the interleukin 6, transforming growth factor beta 1, or platelet-derived growth factor B gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 92:9570–9574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]