Abstract

Background

Limited information is available on added sugars consumption in US infants and toddlers.

Objectives

To present national estimates of added sugars intake among US infants and toddlers by sociodemographic characteristics, to identify top sources of added sugars, and to examine trends in added sugars intake.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of 1 day of 24-hour dietary recall data.

Participants/setting

A nationally representative sample of US infants aged 0 to 11 months and toddlers aged 12 to 23 months (n=1,211) during the period from 2011 through 2016 from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Trends were assessed from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016 (n=2,795).

Main outcome measures

Among infants and toddlers, the proportion consuming any added sugars, the average amount of added sugars consumed, percent of total energy from added sugars, and top sources of added sugars intake.

Statistical analysis

Paired t tests were used to compare differences by age, sex, race/Hispanic origin, family income level, and head of household education level. Trends were tested using orthogonal polynomials. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

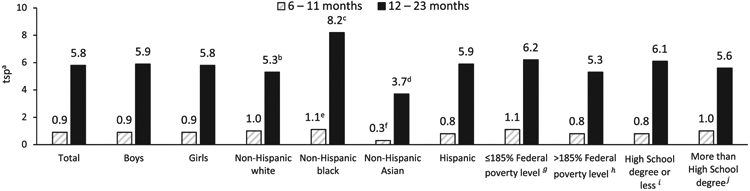

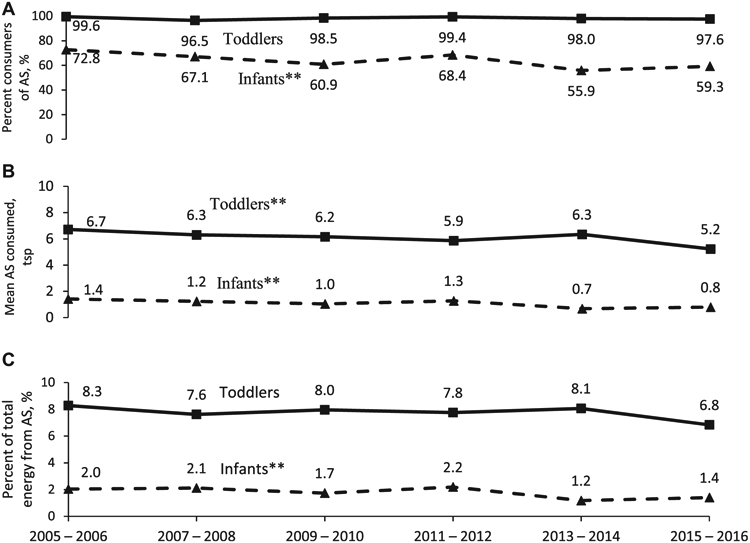

During 2011 to 2016, 84.4% of infants and toddlers consumed added sugars on a given day. A greater proportion of toddlers (98.3%) consumed added sugars than infants (60.6%). The mean amount of added sugars toddlers consumed was also more compared with infants (5.8 vs 0.9 tsp). Non-Hispanic black toddlers (8.2 tsp) consumed more added sugars than non-Hispanic Asian (3.7 tsp), non-Hispanic white (5.3 tsp), and Hispanic (5.9 tsp) toddlers. A similar pattern was observed for percent energy from added sugars. For infants, top sources of added sugars were yogurt, baby food snacks/sweets, and sweet bakery products; top sources among toddlers were fruit drinks, sugars/sweets, and sweet bakery products. The mean amount of added sugars decreased from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016 for both age groups; however, percent energy from added sugars only decreased among infants.

Conclusion

Added sugars intake was observed among infants/toddlers and varied by age and race and Hispanic origin. Added sugars intake, as a percent of energy, decreased only among infants from 2005 to 2016.

Keywords: Nutrition, Survey, Added sugars, Infants, Toddlers

Consumption of added sugars has been associated with detrimental health conditions, such as dental caries,1 asthma,2 obesity,3 altered lipid profiles,4-6 and elevated blood pressure4-6 in children. Meeting adequate intake of essential nutrients, maintaining appropriate weight, and staving off chronic disease leaves little room for the consumption of added sugars.7 Recognizing this, the World Health Organization, a report by the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, and the American Heart Association (AHA) all recommended limiting added sugars consumption to <10% of total energy intake for those aged 2 years and older.8-10 This roughly translates into 9 tsp added sugars per day for men, and 6 tsp for women and children aged 2 to 19 years.10 No national guidance on added sugars exists for infants and toddlers. The only professional body to provide guidance comes from a 2017 statement from the AHA that recommends children younger than 2 years old avoid consuming any added sugars.11

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020 (2015-2020 DGA) provides recommendations for Americans aged 2 years and older. It shows that about 70% of Americans aged ≥2 years exceed recommendations for added sugars intake.7 The current and previous guidelines have not focused on infants and toddlers, principally due to lack of high-quality data.12 Infants and toddlers consuming breast milk are often excluded from analyses because of difficulties related to assessing the amount of breast milk consumed. Consequently, limited information is available on added sugars consumption by US toddlers (aged 12 to 23 months)13 and even less is available for US infants (aged 0 to 11 months).14 In addition, of the few publications on added sugars consumption in infants and toddlers, none have examined trends in added sugars consumption over time. Given the mandate to include recommendations for infants and toddlers aged 0 to 23 months in the upcoming revision of the 2020-2025 DGA,15 more information is needed to provide baseline data that may be relevant to the upcoming 2020-2025 DGA for this age group.12 This could also inform pediatricians about the amounts and sources of added sugars consumed by some of their youngest patients.

This study provides recent national estimates of added sugars consumption among infants (aged 6 to 11 months) and toddlers (aged 12 to 23 months) from 2011 to 2016. We describe the proportion of infants and toddlers consuming added sugars, the amounts they consumed, the percent of energy from added sugars, and the leading sources of added sugars in their diets by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin, family income level (as a percentage of the federal poverty level [FPL]), and head-of-household education attainment. In addition, trends in added sugars consumption from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016 are examined.

METHODS

Study Design

The current study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a complex, stratified, multistage probability sample of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population.16 NHANES is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and detailed information on the study design and methods are available elsewhere.17,18 Briefly, participants receive a detailed in-home interview, followed by a physical examination and dietary interview, at a mobile exam center (MEC). Written parental consent was obtained for infants’ and toddlers’ participation. The NHANES protocol was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. National estimates of added sugars intake were based on data from three survey cycles, 2011-2012, 2013-2014, and 2015-2016. These cycles represent the most recent national data available from NHANES that balance sufficient sample size to produce estimates with greater precision and smaller sampling error, while minimizing the potential influence of secular changes. Ten-year trends in added sugars consumption, beginning with the 2005-2006 cycle, are also presented. Although trend analysis starting in 1999-2000 is possible, changes to both the nutrient database and the instrument used to collect the dietary recall differed, so for consistency 10-year trends19 were evaluated. The unweighted examination response rates for infants and toddlers aged <2 years for 2005-2006, 2007-2008, 2009-2010, 20112012, 2013-2014, and 2015-2016 were 89%, 86%, 87%, 80%, 77%, and 68%, respectively. Response rates for NHANES participants aged younger than 1 year and 1 to 5 years are available on the NHANES website.20

Dietary Intake

The dietary component in NHANES is collected by trained interviewers, using the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Automated Multiple-Pass Method.21 The Automated Multiple-Pass Method uses a computer-assisted dietary interview system that includes a multiple-pass format with standardized probes to collect the type and amount of all food and beverages consumed during the 24 hours previous to the physical examination at the MEC (specifically from midnight to midnight). Proxy interviews, generally provided by a parent (88% mothers and 9% fathers for the study period), captured dietary information for infants and toddlers aged 0 to 23 months. Dietary interviews were assessed for quality; a detailed description of these criteria and methods are described elsewhere.22 Records deemed reliable, including those where breast milk was consumed (n=205), were used in the current analysis. Two 24-hour dietary interviews were collected from each participant, one at the MEC and another 3 to 10 days later by telephone. One 24-hour dietary recall has been shown to be representative of mean population intake because day-to-day variation and random errors cancel out in the case that data are collected evenly across days of the week and seasons of the year.23 Because the objective of this analysis was to describe population-level patterns of added sugars intake, data from a single 24-hour dietary recall were used here; thus, results refer to intake on a given day.

The amount of breast milk consumed is not quantified in the dietary recall; therefore, these records contain missing values for the amounts of energy and nutrients from breast milk. To include breastfed infants and toddlers in the analysis, the amount of breast milk consumed was imputed using the same method as has been used in the Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study, consistent with previous studies.24-27 Briefly, the volume of breast milk consumed was imputed considering the child’s age (in months) and the total volume of other types of milk consumed (ie, infant formula, cow’s milk, and soy milk) during the 24-hour recall period. For infants aged 6 to 11 months fed breast milk as the sole source of milk (n=7), the amount of breast milk consumed was assumed to be 600 mL/day; for partially breastfed infants (n=137), the corresponding amount of breast milk consumed was computed by subtracting the amount of formula/other milks consumed from 600 mL. For toddlers who consumed breast milk (n=61), the amount of breast milk consumed was computed as 89 mL and 59 mL per feeding occasion for children aged 12 to 17 months and 18 to 23 months, respectively.24-27 Breast milk, similar to infant formula, was presumed to have no added sugars.

Added Sugars Intake

Added sugars intake was determined using the Food Patterns Equivalents Database (FPED) (USDA Agricultural Research Service) in conjunction with foods and beverages reported in NHANES. Foods and beverages are disaggregated into 37 USDA Food Patterns components, including teaspoons of added sugars. For example, the FPED disaggregates fruit yogurt into its component parts: added sugars, fats, fruit, and dairy.

Important Sources of Added Sugars

In addition to the FPED, USDA What We Eat In American Food Categories,28 a pre-established, mutually exclusive food classification scheme, was used to characterize foods and beverages into roughly 150 food groups describing foods and beverages as they are commonly consumed. These food categories were collapsed to maintain stable estimates and produce summary categories relevant to the current analysis (KAH) and reviewed by another author (CLO). Differences in category definition were resolved by discussion.

Demographic Characteristics and Socioeconomic Status Variables

Demographic characteristic variables used to describe added sugars intake included age (6 to 11 months or 12 to 23 months), sex (male or female), and race and Hispanic origin (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic). Non-Hispanic participants reporting more than one race are not shown separately but are included in the total. Two dimensions of socioeconomic status were used to describe added sugars intakes: head-of- household educational attainment (less than high school or high school degree/General Equivalency Diploma, and greater than high school education) and family income level relative to the federal poverty level (FPL) (≤185% or >185% of FPL). Studies have shown that families of lower socioeconomic status (ie, income or education level) often use suboptimal weaning diets.29-31

FPL is based on the income-to-poverty ratio, a measure of the annual total family income divided by the federal poverty guidelines32 adjusted for family size and inflation. The income standard for participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children cannot exceed 185% of the poverty guidelines,33 the cutoff of 185% of FPL was used because of its relevance to infants and toddlers’ nutritional status. In 2016, almost half (47%) of all infants in the United States and about one-quarter (24%) of children aged 1 to 4 years received the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children benefits.34

Analysis

Among infants (aged 6 to 11 months) and toddlers (aged 12 to 23 months), the following estimates were calculated: the proportion consuming any added sugars on a given day, the average amount of added sugars consumed, and percent of total energy from added sugars. To identify top sources of added sugars in the diets of infants and toddlers, the population proportion by amount of added sugars consumed and the percent of total energy from added sugars35 was estimated and ranked by decreasing contribution. Table 1 defines the collapsed food categories used.

Table 1.

Food groups and associated What We Eat in America (WWEIA) food group category number used in the current analysis of added sugars intake among US infants and toddlers in the National Health and Examination Survey, 2011-2016

| Collapsed food group category | Food types in food groups | WWEIA categorya |

|---|---|---|

| Baby snacks and sweets | Snacks and sweets labeled for baby | 9012 |

| Breads, rolls, tortillas | Yeast breads, rolls and buns, bagels, English muffins, tortillas | 4202, 4204, 4206, 4208 |

| Sugar and candy | Sugars, honey, sugar substitutes, jams, syrups, toppings, candy containing chocolate, candy not containing chocolate | 5702, 5704, 8802, 8804, 8806 |

| Cereals, cooked and baby cereals | Oatmeal, grits and other cooked cereal, dry and jarred baby cereal | 4802, 4804, 9002 |

| Ice cream, pudding, gelatin | Ice cream, frozen dairy desserts, pudding, gelatins, ices, sorbets | 5802, 5804, 5806 |

| Flavored milk, dairy drinks, | Flavored milk whole, reduced fat, low fat, nonfat, milk shakes | 1202, 1204, 1206, |

| and milk substitutes | and other dairy drinks, milk substitutes | 1208, 1402, 1404 |

| Fruits | Fruit purees, fruits packed in light or heavy syrup | 6002-6018 |

| Fruit drinks | Fruit flavored beverages, fruit nectars, and fruit juice drinks; juice content <100% juice | 7204 |

| Mixed dishes | Mixed dishes—all varieties, pizza, burgers, frankfurter sandwiches, chicken/turkey sandwiches, egg breakfast sandwiches, other sandwiches | 3002-3802 |

| Protein foods | Meats, poultry, seafood, eggs, cured meats/poultry, plant-based protein foods | 2002-2806 |

| Quick breads and bread products | Biscuits, muffins, quick breads, pancakes, waffles, French toast | 4402, 4404 |

| Ready-to-eat cereals | Ready-to-eat cereals, higher sugar (>21.2 g/100 g), ready-to-eat cereals, lower sugar (≤21.2 g/100 g) | 4602, 4604 |

| Savory snacks | Tortilla chips, popcorn, pretzels/snack mix, crackers, saltines | 5004, 5006, 5008, 5202, 5204 |

| Sweet bakery products | Cakes, pies, cookies, brownies, doughnuts, sweet rolls, pastries | 5502, 5504, 5506 |

| Sweetened beverages | Soft drinks, sport and energy drinks, nutritional beverages, smoothies, grain drinks, coffee and tea | 7202, 7206, 7208, 7220, 7302, 7304 |

| Yogurt | Yogurt, baby, Greek and regular | 1820, 1822, 9010 |

WWEIA food groups and category number can be found at https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/dmr-food-categories.

Day 1 dietary weights were applied to the current analysis. Dietary weights account for nonresponse, intake day of the week, differential probabilities of selection, and post-stratification standard. All variance estimates and statistical testing accounted for the complex survey design by using Taylor series linearization. Differences (in means or pro-portions) were determined using adjusted Wald tests (P<0.05). The hypotheses of no linear trend in added sugars intake between 2005-2006 and 2015-2016 were tested using orthogonal contrast matrixes (P<0.05). The current analysis presents mean and 95% Wald CIs, and proportions and 95% Clopper-Pearson CIs, calculated by the Korn and Graubard method.36 The stability of means was evaluated with the relative standard error (RSE); RSE >30 was considered unreliable. The stability of proportions was assessed using NCHS data presentation standards for proportions.37

Data analyses were conducted using SAS software,38 and SUDAAN.39 The current study identified 1,333 infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months who participated in NHANES 2011-2016. Participants who did not have a dietary recall were excluded (n=122), leaving a final sample size of 1,211. Among infants aged 0 to 5 months, added sugars intake was very low; <2%±0.6% consumed any added sugars on a given day, and the amount consumed was small: 0.02±0.01 tsp (data not shown); therefore, this analysis focuses on children aged 6 to 23 months. For trends in added sugars intake from 2005 to 2006 through 2015 to 2016, the sample size was 2,795.

RESULTS

Any Added Sugars Intake

About 60.6% (95% CI, 55.6% to 65.4%) of infants aged 6 to 11 months and 98.3% (95% CI, 97.0% to 99.2%) of toddlers aged 12 to 23 months consumed added sugars on a given day between 2011 and 2016 (Table 2). The proportion of toddlers consuming any added sugars was significantly higher than among infants for all sociodemographic variables (P<0.001). Among infants, variation in the proportion consuming any added sugars did not differ significantly by sex, race and Hispanic origin, family income level, and head-of-household educational attainment. The estimate for non-Hispanic Asian infants was found to be unreliable and was therefore suppressed according to NCHS data standards.37

Table 2.

Proportion of US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months consuming any added sugars on a given day, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2016

| Characteristic | Infants Aged 6-11 mo |

Toddlers Aged 12-23 moa |

Total Children Aged 6-23 mo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | % (95% CIc) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 560 | 60.6 (55.6-65.4) | 651 | 98.3 (97.0-99.2) | 1,211 | 84.4 (81.9-86.7) |

| Boys | 275 | 59.5 (52.4-66.4) | 341 | 98.6 (96.6-99.5) | 616 | 84.7 (81.3-87.7) |

| Girls | 285 | 61.8 (54.5-68.7) | 310 | 98.1 (95.2-99.5) | 595 | 84.0 (80.4-87.2) |

| Race and Hispanic origind | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 185 | 65.2 (55.8-73.9) | 177 | 99.6 (97.2-100.0)i | 362 | 86.5 (81.5-90.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 107 | 51.9 (40.1-63.5) | 144 | 94.1 (86.4-98.1) | 251 | 76.6 (69.5-82.7)k |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 33 | h | 47 | 96.7 (80.9-100)j | 80 | 74.6 (58.7-86.9) |

| Hispanic | 199 | 61.2 (51.6-70.2) | 230 | 98.5 (94.0-99.9) | 429 | 86.0 (81.9-89.5) |

| Family income levele | ||||||

| ≤185% FPLf | 306 | 62.6 (56.9-68.1) | 351 | 98.5 (96.5-99.5) | 657 | 85.3 (82.3-87.9) |

| >185% FPL | 204 | 59.2 (51.8-66.3) | 246 | 98.0 (95.0-99.4) | 450 | 83.8 (79.9-87.1) |

| Head-of-household educational attainmentg | ||||||

| High school degree or less | 254 | 59.2 (51.5-66.5) | 281 | 98.8 (96.6-99.7) | 535 | 84.3 (80.1-87.9) |

| More than a high school degree | 283 | 61.9 (54.4-69.0) | 351 | 98.0 (95.7-99.3) | 634 | 84.8 (81.1-88.0) |

Toddlers aged 12 to 23 months significantly different from infants aged 6 to 11 months for all subgroups (P<0.001).

Unweighted sample size includes responses from all reliable and complete recalls, including infants and toddlers who reported consuming breastmilk on the day of the recall (n=205).

The Korn and Graubard method37 was used to construct 95% CIs.

Estimates for non-Hispanic persons reporting more than one race are not shown separately but are included in the total.

Family income level is missing for 50 participants aged 6 to 11 months and 54 participants aged 12 to 23 months.

FPL=federal poverty level.

Head-of-household educational attainment missing 23 participants for 6-11 months and 19 participants for 12-23 months.

Estimate does not meet National Center for Health Statistics standards of reliability.37

Non-Hispanic white toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic black toddlers (P=0.03).

Standard error based on <8 degrees of freedom.

Non-Hispanic black infants and toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic white (P=0.01) and Hispanic infants and toddlers (P=0.01).

The only significant difference among the proportions of toddlers consuming any added sugars was observed between non-Hispanic white toddlers (99.6%, 95% CI 97.2% to 100.0%) and non-Hispanic black toddlers (94.1%, 95% CI 86.4% to 98.1%) (P=0.03).

Mean Added Sugars Intake

On average, infants consumed almost 1 tsp (0.9 tsp, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.1 tsp) of added sugars on a given day, and toddlers consumed 5.8 tsp (95% CI 5.3 to 6.4 tsp) (Figure 1). Toddlers consumed significantly more added sugars than infants, regardless of sex, race and Hispanic origin, family income level, or head-of-household educational attainment (P<0.001). Among infants, no difference was found in added sugars consumption by sex, family income level, or head-of-household educational attainment. Non-Hispanic Asian infants (0.3 tsp, 95% CI 0.0 to 0.5 tsp) consumed fewer teaspoons of added sugars compared with non-Hispanic white (1.0 tsp, 95% CI 0.1 to 1.4 tsp), non-Hispanic black (1.1 tsp, 95% CI 0.4 to 1.5 tsp) and Hispanic (0.8 tsp, 95% CI 0.5 to 1.0 tsp) infants. However, the RSE of the estimates for both non- Hispanic Asian (RSE=44) and non-Hispanic black (RSE=31) infants exceeded 30 and should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 1.

Mean added sugars consumption (tsp) among US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2016, (n=1,211). atsp=teaspoons. bNon-Hispanic white toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic black (P=0.001) toddlers and non-Hispanic Asian toddlers (P=0.02). cNon-Hispanic black toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic Asian (P<0.001) toddlers and Hispanic toddlers (P=0.01). dNon-Hispanic Asian toddlers significantly different from Hispanic toddlers (P=0.003). eRelative standard error >30. fRelative standard error >30; non-Hispanic Asian infants significantly different from non-Hispanic white infants (P=0.001), non-Hispanic black infants (P=0.04), and Hispanic infants (P=0.002). gFederal poverty level missing for 50 participants 6-11 months. hFederal poverty level missing for 54 participants 12-23 months. iHead-of-household educational attainment missing for 23 participants 6-11 months. jHead-of-household educational attainment missing for 19 participants 12-23 months.

Among toddlers, mean added sugars consumption did not differ by sex, head-of-household educational attainment or family income level, but significant differences were observed by race and Hispanic origin. Non-Hispanic black toddlers (8.2 tsp, 95% CI 6.7 to 9.7 tsp) consumed more added sugars compared with non-Hispanic white (5.3 tsp, 95% CI 4.6 to 6.0; P < .001), non-Hispanic Asian (3.7 tsp, 95% CI 2.6 to 4.7 tsp; P<0.001), and Hispanic toddlers (5.9 tsp, 95% CI 5.0 to 6.8 tsp; P=0.01). In addition to having a lower consumption than non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic Asian toddlers consumed the fewest teaspoons of added sugars, also lower than non-Hispanic white toddlers (P=0.02) and Hispanic toddlers (P<0.01).

Mean Percent of Total Energy from Added Sugars

Overall, added sugars contributed <2% (ie, 1.5%) of total energy intake on a given day for infants and about 8% (ie, 7.6%) of total energy for toddlers (Table 3). The contribution of added sugars to total energy was significantly larger for toddlers compared with infants (P<0.001). The contribution of added sugars to total energy did not vary by sex, head-of-household educational attainment, or family income level among infants. The contribution of added sugars to total energy was lower among non-Hispanic Asian infants (0.6%, 95% CI 0.1% to 1.0%) compared with non-Hispanic white (1.8%, 95% CI 1.1% to 2.4%) and Hispanic infants (1.3%, 95% CI 0.9% to 1.8%). The difference between non-Hispanic Asian and non-Hispanic black infants was not significant. Differences should be interpreted with caution because the RSE was >30 for both non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic Asian infants.

Table 3.

Mean percent of total energy from added sugars among US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2016 (n=1,211)

| Characteristic | Infants 6-11 mo |

Toddlers 12-23 mo |

|---|---|---|

| ←%(95% CIa) → | ||

| Total | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 7.6 (7.0-8.2) |

| Boys | 1.6 (1.0-2.1) | 7.7 (6.9-8.5) |

| Girls | 1.5 (1.0, 2.1) | 7.4 (6.6-8.3) |

| Race and Hispanic originb | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.8 (1.1-2.4) | 7.2 (6.3-8.1)h |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.7 (0.6-2.8)f | 9.5 (7.7-11.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.6 (0.1-1.0)g | 5.2 (3.6-6.7)i |

| Hispanic | 1.3 (0.9-1.8) | 7.8 (6.8-8.8) |

| Family income levelc | ||

| ≤185% FPLd | 1.6 (1.1-2.2) | 7.9 (7.0-8.9) |

| >185% FPL | 1.4 (1.0-1.8) | 7.1 (6.1-8.0) |

| Head-of-household educational attainmente | ||

| High school degree or less | 1.4 (0.7-2.1) | 8.1 (7.1-9.1) |

| More than a high school degree | 1.7 (1.2-2.1) | 7.2 (6.4-7.9) |

Based on Wald test.

Estimates for non-Hispanic persons reporting more than one race are not shown separately but are included in the total.

Family income level missing for 50 participants aged 6 to 11 months and 54 participants aged 12 to 23 months.

FPL=federal poverty level.

Head-of-household educational attainment missing 23 participants for infants group aged 6 to 11 months and 19 participants for toddlers aged 12 to 23 months.

Relative standard error >30.

Relative standard error >30; non-Hispanic Asian infants significantly different from non-Hispanic white infants (P=0.004) and Hispanic (P=0.012) infants.

Non-Hispanic white toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic black toddlers (P<0.02) and non-Hispanic Asian toddlers (P=0.03).

Non-Hispanic Asian toddlers significantly different from non-Hispanic black toddlers (P=0.003) and Hispanic (P=0.005) toddlers.

Among toddlers, the contribution of added sugars to total energy varied by race and Hispanic origin. Added sugars consumption contributed about 5% to total energy consumption among non-Hispanic Asian toddlers (5.2%, 95% CI 3.6% to 6.7%); significantly less than non-Hispanic black (9.5%, 95% CI 7.7% to 11.3%; P<0.01), Hispanic (7.8%, 95% CI 6.8% to 8.9%; P<0.01), and non-Hispanic white (7.2%, 95% CI 6.3% to 8.1%; P=0.03) toddlers. The percent of total energy from added sugars was also significantly higher for non-Hispanic black compared with non-Hispanic white toddlers (P=0.02).

Top Sources of Added Sugars

Table 4 presents the top-eight food and beverage sources of added sugars in the diets of US infants and toddlers; each item accounted for 5% or more of added sugars intake. Among infants, yogurt contributed 17.7% (95% CI 8.7% to 22.6%) to added sugars in the diet, followed by baby snacks and sweets (11.5%, 95% CI 7.1% to 16.0%); sweet bakery products (11.0%, 95% CI 5.6% to 16.5%); and flavored milk, dairy drinks, and milk substitutes (9.6%, 95% CI 1.1% to 18.1%). Fruit drinks contributed 7.1% (95% CI 0.1% to 14.0%) to added sugars intake among infants.

Table 4.

Top eight sources of added sugars in the diets of US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2016 (n=1,211)

| Source of added sugar | Mean contribution to added sugar intake |

|---|---|

| % (95% CIa) | |

| Infants aged 6-11 mo | |

| Yogurt, baby, Greek, and regular | 17.7 (8.7-22.6) |

| Baby snacks and sweetsb | 11.5 (7.1-16.0) |

| Sweet bakery productsc | 11.0 (5.6-16.5) |

| Flavored milk, dairy drinks, and milk substitutes | 9.6 (1.1-18.1) |

| Fruitsd | 8.2 (5.3-11.0) |

| Fruit drinks | 7.1 (0.1-14.0) |

| Sugar and candye | 5.2 (0.0-11.8) |

| Ready-to-eat cerealsf | 5.0 (2.7-7.2) |

| Toddlers aged 12-23 mo | |

| Fruit drinks | 19.6 (13.5-25.7) |

| Sweet bakery productsc | 14.9 (13.0-16.8) |

| Sugar and candye | 10.3 (8.6-12.1) |

| Yogurt, baby, Greek, and regular | 9.0 (5.7-12.3) |

| Sweetened beveragesg | 7.5 (4.7-10.2) |

| Ready-to-eat cerealsf | 6.7 (5.0-8.3) |

| Flavored milk, dairy drinks, and milk substitutes | 5.6 (3.4-7.8) |

| Ice cream, pudding, gelatinh | 5.0 (3.2-6.7) |

Based on Wald test.

Includes products labeled as “baby food”; for example, baby pretzels, apple dessert, and baby food.

Includes cakes, pies, cookies, brownies, doughnuts, sweet rolls, and pastries.

Includes fruit purées and fruits pack in light or heavy syrup.

Includes sugar, honey, sugar substitutes, jams, syrups, toppings, and candy with or without chocolate.

Includes high sugar (>21.2 g/100 g) and low sugar (≤21.2 g/100 g).

Includes soft drinks, sports and energy drinks, nutritional beverages, smoothies, grain drinks, and coffee and tea.

Includes ice cream, frozen dairy desserts, pudding, gelatins, ices, and sorbets.

Among toddlers, fruit drinks accounted for 19.6% (95% CI 13.5% to 25.7%) of added sugars in the diet. Sweet bakery products (14.9%, 95% CI 13.0% to 16.8%), sugar and candy (10.3%, 95% CI 8.6% to 12.1%), yogurt (9.0%, 95% CI 5.7% to 12.3%), and sweetened beverages (7.5%, 95% CI 4.7% to 10.2%) were among the top-five sources of added sugars in the diet of US toddlers.

Trends in Added Sugars Intake from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016

The percent of infants consuming any added sugars declined from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016 (P<0.01). There was no significant change in the percent of toddlers consuming any added sugars during the same time period (P=0.6) (Figure 2A). In addition, mean consumption of added sugars among infants decreased from 1.4 tsp (95% CI 0.9 to 1.9 tsp) during 2005-2006 to 0.8 tsp (95% CI 0.5 to 1.1 tsp) in 2015-2016 (P<0.01). A similar decline was observed among toddlers, from 6.7 tsp (95% CI 6.0 to 7.4 tsp) to 5.2 tsp (95% CI 4.5 to 6.0 tsp) (P=0.02) (Figure 2B). A decline in the percent of total energy from added sugars was observed among infants; from 2.0% (95% CI 0.7% to 4.7%) to 1.4% (95% CI 0.2% to 4.4%) (P=0.01), but not among toddlers (P=0.08) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Trends in percent consumers of added sugars (AS) (A), mean added sugars (teaspoons [tsp]) consumed (B), and added sugars as a percent of total energy intake (C) among US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2006 through 2015-2016 (n=2,795). **Significant linear decrease (P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current analysis demonstrate that added sugars consumption starts early in life and quickly increases. Although the period of data collection (2011 to 2016) predates the AHA 2017 recommendation,11 applying it retrospectively demonstrates how pervasive added sugars are in the US diet. By the time children reach their second birthday, almost all have some exposure to added sugars.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of trends in added sugars consumption among infants and toddlers. The present study found that the amount (in teaspoons) of added sugars consumed has declined over time for infants and toddlers, but the decrease in percent energy from added sugars was only statistically significant among infants. This finding is complementary to patterns observed among older US children and adolescents (aged 2 to 18 years), where added sugars consumption has decreased during the past decade, but the decrease seems to have leveled off in recent years.40-42

No association was found between added sugars intake and sex, family income level, or head-of-household educational attainment, but added sugars consumption was associated with race and Hispanic origin. Although interpretation of added sugars consumption among infants should be approached with caution due to limited sample size, among toddlers, the finding was more robust. Non-Hispanic black toddlers consumed significantly more added sugars than toddlers in all other race and Hispanic origin groups, and the mean consumption amount (8 tsp) exceeded the recommended limit for children aged 2 to 18 years.11 Using NHANES data from 2009 through 2012, Welsh and Figueroa13 found that non-Hispanic black toddlers consumed more added sugars than non-Hispanic white toddlers. The current analysis also found that added sugars accounted for a larger mean percentage of total energy among non-Hispanic black toddlers compared with non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic Asian toddlers. Added sugars contributed nearly 10% of total energy for non-Hispanic black toddlers; this almost matches the recommendation for all individuals aged 2 years and older.7,8

Yogurt, sweet bakery products, and fruit drinks were featured among the top-five sources of added sugars for both infants and toddlers, although their individual rankings were different for infants and toddlers. Among infants, yogurt was the top source of added sugars, followed by baby snacks and sweets. The only other report of sources of added sugars for infants (aged 0 to <1 year) found crackers/popcorn/pretzels/corn chips as the leading source of added sugars.14 The difference likely stems from the approach used to identify important sources of added sugars in the diets of infants and toddlers, The current analysis identified important sources of added sugars using the roughly 150 WWEIA food categories and collapsing categories to maintain stable estimates and produce summary categories relevant to eating patterns in infants and toddlers. Wang and colleagues14 appear to have used 11 predefined categories that were not tailored to the eating patterns of infants and toddlers.

The current analysis found the same top-three sources of added sugars (fruit drinks, sweet bakery products, and sugars/candy) for toddlers as Welsh and Figueroa13 did using NHANES data from 2009 through 2012. Similar to studies in older children (aged 2 to 8 years), sweet bakery products were among the top-three sources of added sugars.14 In the current analysis, fruit drinks were separated from other sweetened beverages; however, in the case that these two categories were collapsed, results would likely match those of older children14 and other studies that have found that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the top source of added sugars in the US diet.43,44

Eating patterns established early in life have been shown to shape later eating patterns.45-47 For example, the odds of consuming SSBs at least once per day was 2.2 times higher among 6-year-olds who had consumed any SSBs before age 1 year, compared with 6-year-olds who had never consumed an SSB before age 1 year.48

This study is not without limitations. For infants and toddlers who reported consuming breast milk, the amount consumed was estimated because it is not collected in NHANES. This could influence the mean percent of total energy from added sugars in subgroup comparisons. Infants and toddlers are unable to report food and beverage consumption for themselves. Plus, because they may be in child care, the person reporting intake may not be the person most familiar with intake. As with any dietary recall, memory is fallible and subject to bias,49,50 particularly related to under- or overreporting of certain food items based on their social influences.51 The food composition tables that underpin NHANES are continuously updated, and a recent change has potential to influence estimates. In the 2011-2012 FPED, “fruit juice concentrates added as ingredients and not diluted, were assigned to added sugars, whereas in the previous FPEDs these were placed in the fruit juice component.”52 National estimates have been unaffected by this change, providing reassurance that our findings of trends in added sugars consumption over time are robust; however, at the individual level differences might be possible.52 Finally, although there was a sufficient sample size to examine added sugars intake among infants and toddlers overall and for most characteristics, for a few groups reliable estimates could not be made.

The current analysis has many strengths. National estimates for infants and toddlers are presented in preparation for periodic revision of the DGAs. In addition, estimates of added sugars intake were presented in teaspoons, a metric easily understood and conveyed to practitioners and the lay public. Two new contributions of this work are the estimation of top sources of added sugars for infants aged 6 to 11 months and estimates of trends over time for both infants and toddlers. In addition, breastfed infants were included in all of the current estimates. This group is often excluded because of the difficulties associated with assigning a consumption amount to breast milk. Although the nutrient values ascribed to breast milk in the food composition tables have not been updated for close to 40 years,53 the data provide a starting point and allows for the inclusion of this important group in national estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

In this nationally representative survey of US infants and toddlers aged 6 to 23 months, almost 85% consumed added sugars on a given day. From 2005-2006 through 2015-2016, fewer infants consumed added sugars, and the amount they consumed decreased and the percent energy from added sugars also decreased. The amount of added sugars consumed also declined for toddlers. Yogurt was the top source of added sugars for infants, and fruit drinks were the top source for toddlers. These findings provide insight into added sugars intake among US infants and toddlers and may inform efforts to reduce added sugars intake and establish healthy dietary practices in early childhood.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Question: What are the amounts, sources, and trends in added sugars intake among US infants and toddlers?

Key Findings: Nearly two-thirds of infants and almost all toddlers consume added sugars. Between 2005 and 2016, fewer infants consumed added sugars, the amount they consumed decreased, and the percent energy from added sugars also decreased. Only the amount of added sugars consumed declined significantly for toddlers.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This work was performed while the authors were employees of the US federal government and the authors did not receive any outside funding.

The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Kirsten A. Herrick, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD..

Cheryl D. Fryar, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD..

Heather C. Hamner, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA..

Sohyun Park, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA..

Cynthia L. Ogden, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD..

References

- 1.Armfield JM, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF, Plastow K. Water fluoridation and the association of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and dental caries in Australian children. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):494–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Jones SE, Pan L. Regular-soda intake independent of weight status is associated with asthma among US high school students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma J, McKeown NM, Hwang SJ, Hoffmann U, Jacques PF, Fox CS. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption is associated with change of visceral adipose tissue over 6 years of follow-up. Circulation. 2016;133(4):370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kell KP, Cardel MI, Bohan Brown MM, Fernandez JR. Added sugars in the diet are positively associated with diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(1):46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosova EC, Auinger P, Bremer AA. The relationships between sugar-sweetened beverage intake and cardiometabolic markers in young children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, Roberts LS, Lustig RH, Fleming SE. Carbohydrate intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in high BMI African American children. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture. 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th edition. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed September 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millen BE, Abrams S, Adams-Campbell L, et al. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee scientific report: Development and major conclusions. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(3):438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120(11):1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vos MB, Kaar JL, Welsh JA, et al. Added sugars and cardiovascular disease risk in children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(19):e1017–e1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raiten DJ, Raghavan R, Porter A, Obbagy JE, Spahn JM. Executive summary: Evaluating the evidence base to support the inclusion of infants and children from birth to 24 mo of age in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans–”the B-24 Project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3 suppl):663S–691S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welsh JA, Figueroa J. Intake of added sugars during the early toddler period. Nutrition Today. 2017;52(2 suppl):S60–S68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Guglielmo D, Welsh JA. Consumption of sugars, saturated fat, and sodium among US children from infancy through preschool age, NHANES 2009-2014. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(4):868–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. Pregnancy and birth to 24 months project. https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/birthto24months. Accessed December 1, 2017.

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics. About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm. Accessed March 1, 2016.

- 17.Curtin LR, Mohadjer LK, Dohrmann SM, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2007–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2013;2(160). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Sample design, 2011–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2(162). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2001-2002 data documentation, codebook and frequencies-dietary interview- total nutrient intakes (DRXTOT_B). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2001-2002/DRXTOT_B.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: NHANES response rates and CPS totals. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ResponseRates.aspx. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 21.Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHANES 2015-2016 Data documentation dietary interview-total nutrient intakes first day (DR1TOT_I). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/DR1IFF_I.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 23.Gibson RS. Principles of Nutritional Assessement. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briefel RR, Kalb LM, Condon E, et al. The Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study 2008: Study design and methods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(12 Suppl):S16–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butte NF, Fox MK, Briefel RR, et al. Nutrient intakes of US infants, toddlers, and preschoolers meet or exceed dietary reference intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(12 Suppl):S27–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewey KG, Finley DA, Lonnerdal B. Breast milk volume and composition during late lactation (7-20 months). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984;3(5):713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piernas C, Miles DR, Deming DM, Reidy KC, Popkin BM. Estimating usual intakes mainly affects the micronutrient distribution among infants, toddlers and pre-schoolers from the 2012 Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey. Public Health Nutr; 2015:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Dietary methods research: Food categories. http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=23429. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 29.Lioret S, Cameron AJ, McNaughton SA, et al. Association between maternal education and diet of children at 9 months is partially explained by mothers’ diet. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(4):936–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smithers LG, Brazionis L, Golley RK, et al. Associations between dietary patterns at 6 and 15 months of age and sociodemographic factors. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(6):658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betoko A, Charles MA, Hankard R, et al. Infant feeding patterns over the first year of life: Influence of family characteristics. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(6):631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health and Human Servces Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Poverty. https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 33.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. WIC eligibility requirements. https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-eligibility-requirements. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 34.US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service Office of Policy Support. National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibles and WIC Program Reach in 2016, final report. Volume 1 Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krebs-Smith SM, Kott PS, Guenther PM. Mean proportion and population proportion: Two answers to the same question? J Am Diet Assoc. 1989;89(5):671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Confidence interals for proportion with small expected number of positive counts estimated from survey data. Survey Methodol. 1998;23:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Center for Health Statistics data presentation standards for proportions. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_175.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2019. [PubMed]

- 38.Statistical Analysis System software release 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.SUDAAN release 11.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Researcher Triangle Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ervin RB, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. Consumption of added sugar among U.S. children and adolescents, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(87):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slining MM, Popkin BM. Trends in intakes and sources of solid fats and added sugars among U.S. children and adolescents: 1994-2010. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8(4):307–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powell ES, Smith-Taillie LP, Popkin BM. Added sugars intake across the distribution of US children and adult consumers: 1977-2012. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(10):1543–1550.e1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Fulgoni VL 3rd. Food sources of energy and nutrients of public health concern and nutrients to limit with a focus on milk and other dairy foods in children 2 to 18 years of age: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2014. Nutrients. 2018;10(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leme AC, Baranowski T, Thompson D, et al. Top food sources of percentage of energy, nutrients to limit and total gram amount consumed among US adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2014. Public Health Nutr; 2018:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okubo H, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Hirota Y. Early sugar-sweetened beverage consumption frequency is associated with poor quality of later food and nutrient intake patterns among Japanese young children: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Nutr Res (New York, NY). 2016;36(6):594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjelland M, Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Nystad W, Andersen LF. Changes and tracking of fruit, vegetables and sugar-sweetened beverages intake from 18 months to 7 years in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pan L, Li R, Park S, Galuska DA, Sherry B, Freedman DS. A longitudinal analysis of sugar-sweetened beverage intake in infancy and obesity at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S29–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park S, Pan L, Sherry B, Li R. The association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake during infancy with sugar-sweetened beverage intake at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S56–S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahluwalia N, Dwyer J, Terry A, Moshfegh A, Johnson C. Update on NHANES dietary data: Focus on collection, release, analytical considerations, and uses to inform public policy. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(1):121–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subar AF, Freedman LS, Tooze JA, et al. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. J Nutr. 2015;145(12): 2639–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hebert JR, Clemow L, Pbert L, Ockene IS, Ockene JK. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(2):389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Friday JE, Thoeric RC, Moshfegh AJ. Food patterns equivalents database 2011-2012: Methodology and user guide. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/fped/FPED_1112.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu X, Jackson RT, Khan SA, Ahuja J, Pehrsson PR. Human milk nutrient composition in the United States: Current knowledge, challenges, and research needs. Curr Dev Nutr. 2018;2(7):nzy025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.