Abstract

The subsequent degradation pathway of the dihydride–Meisenheimer complex (2H––TNT), which is the metabolite of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) by old yellow enzyme flavoprotein reductases of yeast and bacteria, was investigated computationally at the SMD/TPSSH/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory. Combining the experimentally detected products, a series of protonation, addition, substitution (dearomatization), and ring-opening reaction processes from 2H––TNT to alkanes were proposed. By analyzing reaction free energies, we determined that the protonation is more advantageous thermodynamically than the dimerization reaction. In the ring-opening reaction of naphthenic products, the water molecule-mediated proton transfer mechanism plays a key role. The corresponding activation energy barrier is 37.7 kcal·mol–1, which implies the difficulty of this reaction. Based on our calculations, we gave an optimum pathway for TNT mineralization. Our conclusions agree qualitatively with available experimental results. The details on transition states, intermediates, and free energy surfaces for all proposed reactions are given and make up for a lack of experimental knowledge.

Introduction

TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene) was one of the most widely used explosives around the world. Since TNT is highly toxic and mutagenic,1 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has rated TNT as a possible human carcinogen.2 The explosives can be released into the environment during manufacture, transportation, storage, disposal, and live-fire training; thus, they are damaging to the environment and human health. The total area of operational ranges in the United States contaminated with munitions constituents is estimated to be more than 16 million acres, with clean-up of active ranges estimated by the U.S. Department of Defense to cost about $16–165 billion.3 Several chemical-based methods, such as alkaline hydrolysis4 and redox reactions using iron-bearing materials5 have been proven to be too cost-intensive for the scale of contaminated areas. Biodegradation or phytoremediation has been developed as a potentially cost-effective and eco-friendly method to clean up explosive-contaminated soil.6−12

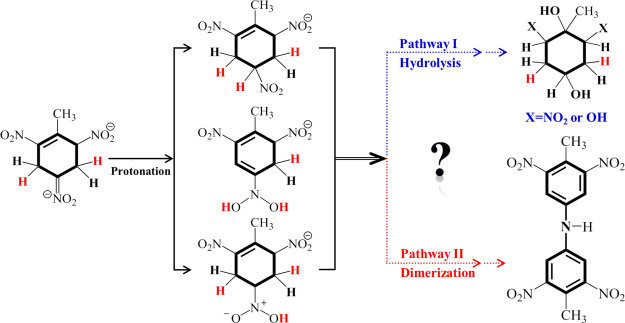

Two main pathways of TNT biotransformation have been proposed, that is, the reduction of nitro groups and the reduction of the aromatic ring.6,13,14 Compared with the nitro reduction, the advantage of Meisenheimer pathway lies in nontoxic intermediate metabolites and the promising potential for the fission of aromatic ring since Meisenheimer complexes destroy the most stable aromatic ring of TNT.6 Although research on Meisenheimer reduction of TNT, such as microorganisms13,15 and enzymatic mechanisms,10,11 has made significant progress, these works have been limited to the processes before Meisenheimer complexes. Unfortunately, the subsequent transformation of Meisenheimer complexes is still controversial (Figure 1). For example, Vorbeck et al.16 observed the protonation of a Meisenheimer–dihydride complex (2H–−TNT) in aqueous solution and then hydrolysis, which results in the formation of cyclohexane with hydroxyl groups. French et al.17 discovered that the hydride–Meisenheimer complex (H–−TNT) can produce nitrite anions by denitrification, which can be metabolized by some microorganisms as nitrogen sources. However, Wittich et al.18 indicated that 2H––TNT can react with the intermediate 4-hydroxylamine-2,6-dinitrotoluene to form dimer products and nitrite anions. Then, they also demonstrated that the nitrite anions are from the protonated 2H––TNT by isotope labeling.19 These works emphasized that all reactions, except denitrification, are chemical processes without the involvement of enzymes and only provided the possible products on the subsequent transformation of 2H––TNT. In fact, the lack of the key ring-opening reaction mechanisms has limited the development of complete mineralization of TNT based on the Meisenheimer pathway.

Figure 1.

Two major reported pathways for the transformation of dihydride–Meisenheimer complex 2H––TNT of TNT. The above one (blue) is protonation followed by hydrolysis, and the other (red) is protonation followed by dimerization.

In this work, we explored the possible ring-opening degradation pathways of TNT, i.e., the subsequent transformation process of Meisenheimer complex 2H––TNT from the biodegradation of the old yellow enzyme family (OYE), by means of density functional theory (DFT) in quantum chemistry (QM) methods. Indeed, QM and experimental data can provide a powerful research method to delineate the detailed TNT degradation pathways.20−22 To the best of our knowledge, the theoretical simulations on spontaneous ring-opening reaction pathways of 2H––TNT are rare so far. Based on the experimental result,16−19 we mainly focus on the reaction mechanisms of 2H––TNT. Our DFT investigations, combined with previous simulations,10,11 will provide a meaningful help for the comprehensive understanding of biodegradation of TNT by OYEs and promote the devolvement of bioremediation technologies for removal of TNT and other energetic compounds.

Results and Discussion

Comparison and Selection of Functionals

First, the experimental UV–vis absorption spectra of two Meisenheimer structures (2H–−TNT and 2H––TNT·H+) were found to screen the suitable functionals.13,16 We chose five typical functionals (B3LYP, M06-2X, MPWLYP, PBE1PBE, and TPSSH) and two basis sets (6-311+G** and cc-PVTZ) to calculate the UV–vis absorption spectra of two Meisenheimer structures, which are H––TNT and 2H––TNT·H+, respectively.

Comparing the calculated data in Table 1, we can find that the functional TPSSH with 6-311+G(d,p) basis set provides the smallest deviation of absorption peaks with the experimental results. Although our calculated UV–vis spectra still have deviations of 15–20 nm to experimental data, it is clear that the biggest deviation between different experimental results is also 28 nm.

Table 1. Calculated and Experimental Absorption Peaks of UV–vis Spectra for H––TNT and 2H—−TNT·H+.

| UV values

(nm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| functionals | biases sets | H––TNT | 2H—−TNT·H+ |

| B3LYP | 6-311+G(d,p) | 231, 452, 529 | 250, 417 |

| cc-PVTZ | 220, 430, 513 | 242, 400 | |

| M06-2X | 6-311+G(d,p) | 206, 400, 487 | 212, 417 |

| cc-PVTZ | 201, 383, 474 | 205, 400 | |

| MPW1LYP | 6-311+G(d,p) | 220, 440, 518 | 236, 415 |

| cc-PVTZ | 212, 418, 501 | 228, 397 | |

| PBE1PBE | 6-311+G(d,p) | 213, 429, 512 | 228, 406 |

| cc-PVTZ | 208, 410, 498 | 222, 390 | |

| TPSSH | 6-311+G(d,p) | 240, 460, 534 | 255, 413 |

| cc-PVTZ | 235, 440, 519 | 248, 398 | |

| experiment | Vorbeck et al16 | 255, 477, 578 | 267, 445 |

| Ziganshin et al13 | 256, 480, 550 | 266, 426 | |

Then, we also compare the description capabilities of five functionals (with 6-311+G**) for the structure of TNT in the ground state (see Table S1 in the Supporting Information). Compared with the experimental results, it can be found that the five functionals have similar accuracy in the description of the bond angle. In terms of bond length, the accuracy of the functional MPW1LYP is slightly worse, and the remaining four have better accuracy. By comparing with the above two experimental results (UV and crystal data), we finally choose the TPSSH/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory in this work, and we believe that it can accurately describe the structural and energy changes of the relevant stationary points in reaction pathways.

Protonation of the Enzyme-Catalyzed Product 2H–-TNT

The processes and mechanisms of TNT transferring to the dihydride–Meisenheimer complex (2H––TNT) by OYEs have been relatively clearly understood.10−14 However, the transformation process after the product 2H––TNT is controversial. Although two main pathways, hydrolysis and dimerization, were proposed,18,19 the protonation reaction in the previous step is basically no objection, as shown in Figure 1. Here, we mainly explored the possible reaction sites and stable products for the protonation of 2H––TNT by calculating Fukui functions and free energy of reaction (2H–−TNT + H+ → 2H—−TNT·H+). Since ΔG of H+ is 0 kcal·mol–1, the reference value for the free energy of reaction is only equal to that of 2H––TNT (i.e., the reactant). First, Figure 2 gives the structures of seven possible first-step protonation products (P1–P7) and the corresponding Gibbs free energy variation (ΔGprotonation = ΔGproducts – ΔGreactants). The first five products (P1–P5) are the direct products of the first-step protonation reaction and the last two (P6 and P7) are the hydrogen transferring tautomeric products of P2 and P4, respectively.

Figure 2.

Structures and reaction free energy ΔGprotonation (abbreviated as ΔGprot) of the protonation reaction for 2H–-TNT (P0), its seven first-step protonation products (P1–P7, which corresponds to blue hydrogen), and four second-step protonation products (P8–P11, pink hydrogen); the unit of ΔGprotonation is kcal·mol–1.

Judging from the data of ΔGprotonation, the most probable product of the one-step protonation reaction for 2H–1−TNT is P1 (−148.9 kcal·mol–1), and the most unlikely one is P5 (−83.0 kcal·mol–1). The product 2H—−TNT·H+ of the first-step protonation of 2H––TNT still has a negative charge, and it is clear that the second-step protonation reaction can occur if there are sufficient protons. Therefore, we performed the ΔGprotonation calculation for possible products (P8–P11 of Figure 2) of the second-step protonation of P1 and P2, respectively. From Figure 2, we can know that the protonated products of P1 have an energy advantage over those of P2.

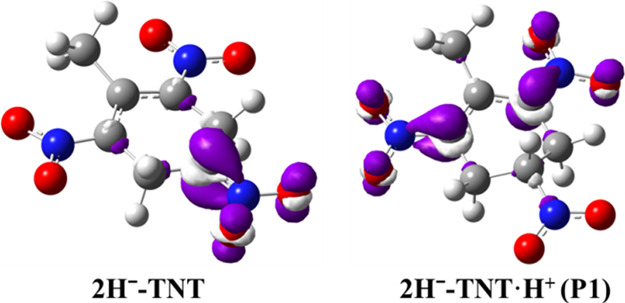

To further identify the possible transfer sites of the protonation process, we calculated the Fukui function of 2H––TNT and P1, which can determine the optimal sites for the electrophilic attack of H+. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the Fukui function isosurface, and the purple part represents the position where the electrophilic attack reaction is most likely to occur. As shown in Figure 3, the para-carbon (methyl) of 2H––TNT is the most likely site for electrophilic attack, and the optimal electrophilic reaction sites for P1 are the two carbons on the phenyl ring at the ortho-position of the methyl group. This is well consistent with the prediction of the reaction free energy. Therefore, we can speculate that the most likely path for the protonation reaction of 2H––TNT is 2H––TNT →P1 → P8. Of course, the possibility of other paths cannot be completely ruled out.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the Fukui function isosurface on different atoms of 2H––TNT and its protonated product P1,.

Hydrolysis Process of Protonated Products

Although the above calculations of ΔGprotonation and Fukui functions indicate that P8 is the most likely product for 2H––TNT after the second-step protonation, P8 is still not the compound H1 found experimentally.16 Here, our task is to reveal the reaction mechanism of the conversion from P8 to H1 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Fate of Protonation Products of Dihydride Meisenheimer Complex 2H–-TNT of TNT.

It is not difficult to see that the experimental product H1 can be obtained from P8 through two consecutive hydrolysis reactions (i.e., addition and substitution reactions). There are two possibilities for this hydrolysis process: one is the addition reaction followed by the substitution reaction, and the other is the opposite. We fully investigated the two routes, including the search for the transition states (TSs), Gibbs free energy barriers (ΔG‡), free energies of reactions (ΔGR), and so on. In the first step of the addition reaction, we searched two TSs, TS1 and TS3, which means that there are two reaction mechanisms in the first step of the H2O-addition reaction, as shown in Figure 4a,b.

Figure 4.

Reaction pathway of the conversion from P8 to H1 and the corresponding free-energy profiles. (a) H2O addition (to the benzene ring) followed by the substitution mechanism for the conversion of P8 to H1 through TS1 and TS2; (b) H2O addition (to the nitro group) followed by the substitution mechanism for the conversion of P8 to H2 through TS3 and TS4; (c) first substitution followed by the H2O addition and the proton transfer reaction for the conversion of P8 to H1 through TS5, TS6, and TS7. The distances are given in Angstroms.

In Figure 4a, the IRC calculation shows that TS1 connects the two associated minima along the reaction path with a high ΔG‡ of 55.7 kcal·mol–1, the reactant P8 and the addition product H2, which corresponds to the direct Michael addition mechanism of H2O. From the variation in the bond length of TS1, the hydrogen of H2O dissociates first (1.195 Å), then the dissociated hydrogen binds to the C atom adjacent to CH3 (1.512 Å), and the hydroxyl group binds to the C atom linked with CH3 (1.556 Å). In the absence of hydrogen bonding induction, the dissociation of water determines the high barrier of this reaction. However, TS3 connects reactant P8 and intermediate structure IN1 with a relatively low ΔG‡ of 34.2 kcal·mol–1, which is about 21.5 kcal·mol–1 lower than TS1. The reason why the barrier of this step is low is because the NO2 group adjacent to CH3 first forms a hydrogen bond with a H atom of the attacked H2O (1.751 Å), as shown in Figure 4b. IN1 then undergoes a water molecule-mediated proton transfer reaction to product H2. Judging from the reaction distance (1.418 Å) of TS4, this step also has the formation of a hydrogen bond; therefore, its ΔG‡ is 33.2 kcal·mol–1 (Figure 4b). Obviously, the reaction from P8 to H2 through TS3 has more kinetic advantages.

As for the transition from H2 to H1, it is a nucleophilic substitution reaction. A H2O molecule attacks the carbon attached to the nitro group and then generates the final experimental product H1 and a nitrous acid through TS2. Based on the charge data (Table S2), the nitro group with a strong electron-withdrawing ability and the electron-deficient benzene ring find it difficult to dissociate, resulting in a higher ΔG‡ (46.3 kcal·mol–1, Figure 4a). When we try to perform the substitution reaction first, its ΔG‡ is also 46.1 kcal·mol–1 (Figure 4c), which is very consistent with the data of Figure 4a. The substitution product H3 can pass through the route similar to that of Figure 4b to generate the final H1.The highest ΔG‡ is 35.0 kcal·mol–1, which corresponds to TS6 (the change of reaction distance is very similar to TS3). In this way, this substitution reaction (ΔG‡ ≈46 kcal·mol–1) has become the rate-determining step for the formation of the final experimental product H1. From the structural analysis of TS5, we can know that the high energy barrier for this reaction is the rupture of the hydrogen–oxygen bond of a water molecule. In fact, previous work showed that, if the nitro group is substituted by other groups, such as OH–,20 OH·,21 or H·,23 the energy barriers are very low. Therefore, we believe that this reaction is possible in the real complex environment; this is why product H1 (including several similar hydroxyl substitution products, Figure 1) can be detected in the experiments.

Ring-Opening Reaction

The products H1 and H4 in Scheme 2 are detected by experiments.17,18 However, for the subsequent ring-opening reaction and corresponding products, there is no conclusive evidence. Based on the proposed ring-opening mechanism of picric acid24 and the bond order analysis, we speculated on several possible ring-opening sites, mainly focused on the single bond between carbon atoms and polar groups. As shown in Scheme 2, the cyclic compound H1 would produce two main products, R12 and R34, by the possible broken sites, i.e., the bonds of C1–C2 and C3–C4. H4 would produce four main products, R12′, R12″, R23,and R34, because it has three possible broken sites, i.e., the bonds of C1–C2, C2–C3, and C3–C4. The corresponding ring-opening products undergo structural inversion and become a chain structure. The calculated ΔGR of ring-opening reactions shows that only the cleavage of the bond between C1 and C2 is thermodynamically favorable, and the corresponding reaction should proceed spontaneously due to ΔGR < 0.

Scheme 2. Corresponding Products for Subsequent Ring-Opening Reaction of Experiment-Detected Products H1 and H4.

After determining the position of the ring opening, we hypothesized the mechanism of the hydrolytic ring-opening reaction. Through the transition state search and the confirmation of IRC calculation, we finally ensured the existence of the transition state TS8 (Figure 5). Interestingly, although the water molecule is involved in the reaction, it does not add to the products like the general hydrolysis reaction. It mediates the proton transfer from the hydroxyl to the nitro group, which results in the ring opening of the cyclic reactant H1. The ΔG‡ for this reaction is 37.7 kcal·mol–1. Then, the generated intermediate IN3 undergoes a proton transfer reaction (ΔG‡ = 30.1 kcal·mol–1) to form the alkane product R12. From the previous analysis (Figure 4), we can see that due to the participation of hydrogen bonding, the barrier of such reactions is generally in the range of 30 to 40 kcal·mol–1. From Figure 5, we can know that the corresponding potential energy surface (PES) for the ring-opening reaction pathway exists a relatively high barrier (ΔG‡ = 37.7 kcal·mol–1), suggesting that this reaction finds it difficult to occur at the room temperature. In fact, water has been shown to be important as a catalyst mediating proton transfer.25 Moreover, the number of water molecules participating in the reaction and their conformation at the reaction center will obviously affect the free energy barrier.26,27 Therefore, we cannot deny the possibility of this reaction because we have not found the transition state corresponding to a lower free energy barrier.

Figure 5.

Free-energy profiles, transition states, and products for the ring-opening reaction of H1.The process includes two transition states (TS8 and TS9) and an intermediate (IN3). The distances are given in Angstroms.

Dimerization Process

The dihydride Meisenheimer complex (2H–−TNT) from the benzene ring reduction of TNT can undergo a condensation reaction with the 4-hydroxylaminodinitrotoluene (4HA) from the nitro group reduction of TNT and release secondary diarylamines and nitrite as the end products of this environmentally relevant reaction sequence.18,19 Although the experiment has shown that the nitrite as the nitrogen source of the microorganism originates from the microbiologically generated 2H––TNT,19 other information on this reaction is still absent. It is impossible to design a detailed reaction to calculate the ΔG‡ information for this dimerization reaction, but the reaction equation can be balanced according to the experimental products to obtain the thermodynamic ΔGR. Scheme 3 gives the complete equation of the dimerization reaction and the results of ΔGR. The main products are the final dimer D1 detected by experiments and the nitrite; other products are determined by the equilibrium of reaction equations.

Scheme 3. Four Possible Pathways for Dimerization Process of 2H––TNT.

Clearly, ΔGR of all four reactions are less than zero, as shown in Scheme 3. It means that all dimerization reactions are thermodynamically advantageous and can proceed spontaneously. The dihydride–Meisenheimer complex 2H––TNT would undergo rearomatization and condensation to release nitrite and H2 under acidic conditions (see reaction 1 in Scheme 3), which has the most negative ΔGR (−199.1 kcal·mol–1). When its protonation product P2 can generate the same products under neutral conditions (reaction 3), the ΔGR is equal to −59.6 kcal·mol–1, which is an increase of 139.5 kcal·mol–1 compared to that of 2H––TNT’s reaction. The value coincides with the calculated free energy (ΔGprot) of protonation reaction of 2H––TNT to P2 (Figure 2). This shows that under acidic conditions, the protonation of 2H––TNT will occur first followed by dimerization.

Under alkaline conditions, the ΔGR of the dimerization reaction between P2 and 4HA (reaction 4) is −41.9 kcal·mol–1, which is more negative than that of the reaction between 2H––TNT and 4HA (−18.1 kcal·mol–1, reaction 2). Therefore, after the protonation of 2H––TNT, it is thermodynamically beneficial to dimerization reactions with hydroxylaminodinitrotoluene.

Comparison

Based on the products detected by experiments, we calculated the ΔGR and ΔG‡ information of the subsequent conversion processes that start from the Meisenheimer–dihydride complex (2H–−TNT, ΔGR = 0) metabolized by some flavin reductases, which includes protonation reactions, hydrolysis reactions, ring-opening reactions, and dimerization reactions. The corresponding PESs for these two pathways are summarized in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6, the ΔGR of two-step protonation reactions of 2H––TNT has a significant decrease; this is very thermodynamically advantageous. The dimerization reaction has a similar trend on ΔGR. This may also explain why the related products of these two reactions were detected experimentally. From PES profiles, we can judge that the protonation reaction is theoretically more advantageous.

Figure 6.

Free-energy profiles for two conversion pathways of the dihydride–Meisenheimer complex (2H–−TNT). The first pathway includes protonation and dimerization processes (black line).The second pathway includes protonation, hydrolysis reaction, and ring-opening reaction (blue line). The structures of transition states and stationary points can be seen in Figures 4 and 5 and Figure S1 (see the Supporting Information), respectively.

However, for the subsequent hydrolysis and ring-opening reactions of two-step protonated products, such as P8, their ΔG‡ values are in the range of 28.0 to 46.3 kcal·mol–1. It means that these reactions find it more difficult to occur at room temperature from the kinetic point of view. In general, the calculations of quantum chemistry would overestimate the ΔG‡ values for these reactions. In addition, the rate-determining step (ΔG‡ ≈ 46 kcal·mol–1) for subsequent reactions is the substitution reaction on the nitro group (Figure 4). The reason is that the nitro group with a strong electron-withdrawing ability possesses most of the negative charge of the reactants; it is difficult to separate from the positively charged benzene ring (see the charge data in Table S2). The other high energy barrier comes from the cleavage reaction of oxygen–hydrogen bonds of water molecules without the participation of hydrogen bonding. According to previous research results,20,21,23 if there are ions (OH–) or free radicals (OH·) in the reaction system, the substitution reaction of nitro groups extremely easily occurs. If the ΔG‡ of the rate-determining reaction is overcome, the ΔG‡ of other reactions will fall back to the level of 33.0 ± 3.49 kcal·mol–1. Therefore, in theory, we can think that TNT can achieve mineralization according to the following pathway: first, TNT was reduced to the Meisenheimer–dihydride complex 2H––TNT by OYEs; second, 2H––TNT underwent a series of protonation, addition, and substitution processes to achieve dearomatization and generated the naphthenic product H1; finally, H1 was mineralized into small molecules through the hydrolytic ring cleavage reaction.

Conclusions

Environmental problems arising from energetic materials in current and former conflict zones, manufacturing sites, and military ranges have been an international concern. Among them, the most broadly used TNT is a major pollutant and its persistence in the environment presents health and environmental concerns. The mineralization of TNT has always been a challenge due to the highly inactivated π system of its aromatic ring. The aromatic ring reduction pathway mediated by OYE flavoprotein reductases can generate the products of Meisenheimer complexes by addition of one or two hydride ions to the aromatic ring, which allows the fission of the aromatic ring and is highly promising from the viewpoint of environment friendly remediation of TNT-contaminated sites.13 However, no proof for the mineralization of TNT has been found.

After TNT is biometabolized to Meisenheimer–hydride complexes (mainly 2H––TNT), there is controversy on the continuing transformation process. In this work, we investigated the whole subsequent conversion process and the possibility of ring-opening reaction at the SMD/TPSSH /6-311+G(d,p) level, including Gibbs free energies of reactions (ΔGR), reaction activation energy barriers (ΔG‡), geometries of transition states and intermediates, and so on.

By comparing the calculated and experimental UV absorption spectra of two Meisenheimer complexes, we ensured that the level of the TPSSH functional and 6-311+g(d,p) group with the SMD solvation model can better describe the system we are concerned about. The results show that both protonation and dimerization reactions can occur spontaneously thermodynamically. This is why the corresponding products are easily detected by experiments. In terms of the extent of ΔGR, the protonation reaction is more advantageous, especially under acidic conditions. As for the dimerization reaction, the participation of nitro reduction products is also required. Therefore, the protonation reaction should occur more easily than the dimerization reaction theoretically.

For the product of two-step protonation reactions, the subsequent dearomatization and ring-opening reactions have a relatively high ΔG‡. Thus, we can judge that such reactions find it difficult to occur at room temperature. This may be the reason why mineralization products of TNT have not been found in experiments. However, it does not exclude the participation of other active reactants, which will significantly reduce the ΔG‡ and even change the reaction mechanism, making the reaction easier. Finally, based on the simulation results of this work, we still gave a kind of speculation on the optimum pathway for TNT mineralization.

In conclusion, the possible mechanism of Meisenheimer–dihydride complexes of TNT from the metabolism of several flavoprotein reductases (or microorganisms) is fully explored in detail.28 It is of great significance for the design and development of new technologies that can fully degrade the nitro aromatic explosives.

Computational Methods

All calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 suite of programs.29 The solvent effect was taken into account by using the SMD (pauling) solvent model in water (the dielectric constant is 78.4).30 The choice of the functional and basis sets in DFT calculations is crucial to the accuracy of the results. By comparing with the experimental UV–vis absorption spectra of H––TNT and 2H—TNT·H+ (Table 1), we finally determined the hybrid functional of TPSSH with a basis set of 6-311+G(d,p) to optimize the relevant stationary points in reaction pathways. All stationary points were further characterized as either local minima (intermediates, no imaginary frequency) or saddle points (transition states, one and only one imaginary frequency). In addition, the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC)31 path was also traced to check the energy profiles connecting each transition state to the two associated minima of the proposed mechanism.

Additionally, the zero-point vibrational energies and the corrections in enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy were also determined by the calculation of the analytic harmonic vibrational frequencies at the same theory level as that of the geometry optimization. Gibbs free energies of all considered species were calculated using the standard expression ΔG = ΔH – T·ΔS, where ΔG is the activation Gibbs free energy, ΔH and ΔS are the activation enthalpy and entropy, respectively, and T is the absolute temperature (298.0 K in this study). The Multiwfn 3.2 program32 was utilized to calculate the Hirshfeld charges33 and Fukui functions,34 using the checkpoint file from the above Gaussian calculations as the input file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the financial support from the Foundation of State Key Laboratory of NBC Protection for Civilian (SKLNBC2018-18) and National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (no. 21905260).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02162.

Author Contributions

§ Y.Z. and Z.Y. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wei T.; Zhou Y.; Yang Z. l.; Yang H. Progress of Toxicity Effects and Mechanisms of Typical Explosives. Chin. J. Energ. Mater. 2019, 27, 558–568. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Technical fact sheet-2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT). https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/frrofactsheet contaminant TNT January 2014 final.pdf, 2014.

- United States General Accounting Office. Department of Defense operational ranges, more reliable cleanup cost estimates and a proactive approach to identifying contamination are needed. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA435939&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf, 2004.

- Sviatenko L. K.; Gorb L.; Leszczynska D.; Okovytyy S. I.; Shukla M. K.; Leszczynski J. In silico kinetics of alkaline hydrolysis of 1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazinane (RDX): M06-2X investigation. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2017, 19, 388–394. 10.1039/C6EM00565A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. Y.; Yoon H. S.; Jeong T. Y.; Kim S. D.; Kim D. W. Reduction and persulfate oxidation of nitro explosives in contaminated soils using Fe-bearing materials. Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts 2016, 18, 863–871. 10.1039/C6EM00223D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylott E. L.; Lorenz A.; Bruce N. C. Biodegradation and biotransformation of explosives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 434–440. 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard T.; Weidhaas J. Biodegradation of IMX-101 explosive formulation constituents: 2,4-Dinitroanisole (DNAN), 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazol-5-one (NTO), and nitroguanidine. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 372–379. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston E. J.; Rylott E. L.; Beynon E.; Lorenz A.; Chechik V.; Bruce N. C. Monodehydroascorbate reductase mediates TNT toxicity in plants. Science 2015, 349, 1072–1075. 10.1126/science.aab3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Rylott E. L.; Bruce N. C.; Strand S. E. Genetic modification of western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii) for the phytoremediation of RDX and TNT. Planta 2019, 249, 1007–1015. 10.1007/s00425-018-3057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Chen J.; Zhou Y.; Huang H.; Xu D.; Zhang C. Understanding the hydrogen transfer mechanism for the biodegradation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene catalyzed by pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase: molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 12157–12165. 10.1039/C8CP00345A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.; Wei T.; Huang H.; Yang H.; Zhou Y.; Xu D. Insights into the Biotransformation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene by the Old Yellow Enzyme Family of Flavoproteins. A Computational Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 11589–11598. 10.1039/C8CP07873D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-González M. Y.; Chandra R.; Castillo-Zacarias C.; Robledo-Padilla F.; Rostro-Alanis M. D. J.; Parra-Saldivar R. Biotransformation and degradation of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene by microbial metabolism and their interaction. Def. Technol. 2018, 14, 151–164. 10.1016/j.dt.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. N.Biological Remediation of Explosive Residues; Springer International Publishing Switzerland. Springer International Publishing Switzerland,2014. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. E.; Rathbone D. A.; Scrutton N. S.; Bruce N. C. Biotransformation of Explosives by the Old Yellow Enzyme Family of Flavoproteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 3566–3574. 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3566-3574.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve-Núñez A.; Caballero A.; Ramos J. L. Biological Degradation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001, 65, 335–352. 10.1128/MMBR.65.3.335-352.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorbeck C.; Lenke H.; Fischer P.; Spain J. C.; Knackmuss H.-J. Initial reductive reactions in aerobic microbial metabolism of2,4,6-trinitrotoluene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 246–252. 10.1128/AEM.64.1.246-252.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French C. E.; Nicklin S.; Bruce N. C. Aerobic Degradation of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene by Enterobacter Cloacae PB2 and by Pentaerythritol Tetranitrate Reductase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2864–2868. 10.1128/AEM.64.8.2864-2868.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittich R. M.; Haïdour A.; Van Dillewijn P.; Ramos J.-L. OYE Flavoprotein Reductases Initiate the Condensation of TNT-Derived Intermediates to Secondary Diarylamines and Nitrite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 734–739. 10.1021/es071449w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittich R. M.; Ramos J. L.; Dillewijn P. V. Microorganisms and Explosives: Mechanisms of Nitrogen Release from TNT for Use as an N-Source for Growth. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2773–2776. 10.1021/es803372n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviatenko L.; Kinney C.; Gorb L.; Hill F. C.; Bednar A. J.; Okovytyy S.; Leszczynski J. Comprehensive investigations of kinetics of alkaline hydrolysis of TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene), DNT (2,4-dinitrotoluene), and DNAN (2,4-dinitroanisole). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 10465–10474. 10.1021/es5026678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.; Zeng Q.; Zhou Y.; Zeng Q.; Wei X.; Zhang C. A DFT Study Toward the Reaction Mechanisms of TNT With Hydroxyl Radicals for Advanced Oxidation Processes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 3747–3753. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b03596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Liu X.; Jiang W.; Shu Y.; Xu G. A theoretical insight into the reaction mechanisms of a 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene nitroso metabolite with thiols for toxic effects. Toxicol. Res. (Camb) 2019, 8, 270–276. 10.1039/C8TX00326B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Liu X.; Jiang W.; Shu Y. Theoretical insight into reaction mechanisms of 2,4-dinitroanisole with hydroxyl radicals for advanced oxidation processes. J. Mol. Model. 2018, 24, 44. 10.1007/s00894-018-3580-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K. W.; Knackmuss H. J.; Heiss G. Nitrite Elimination and Hydrolytic Ring Cleavage in 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol (Picric Acid) Degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 70, 2854–2860. 10.1128/AEM.70.5.2854-2860.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerting T.; Liedl K. R. Water-Mediated Proton Transfer: A Mechanistic Investigation on the Example of the Hydration of Sulfur Oxides. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 5137–5145. 10.1021/jp0038862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. H.; Ren S. J.; Wei X. G.; Zeng Y.; Gao G. W.; Ren Y.; Zhu J.; Lau K. C.; Li W. K. Concerted or stepwise mechanism? New insight into the water-mediated neutral hydrolysis of carbonyl sulfide. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 3503–3513. 10.1021/jp5021559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Kumar M.; Zhu C.; Zhong J.; Francisco J. S.; Zeng X. C. Near-Barrierless Ammonium Bisulfate Formation via a Loop-Structure Promoted Proton-Transfer Mechanism on the Surface of Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1816–1819. 10.1021/jacs.5b13048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzafestas K.; Ahmad L.; Dani M. P.; Grogan G.; Rylott E. L.; Bruce N. C. Structure-Guided Mechanisms Behind the Metabolism of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene by Glutathione Transferases U25 and U24 That Lead to Alternate Product Distribution. Front. Plant. Sci. 2018, 9, 1846. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J. T. G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.01; Gaussian: Wallingford, CT. 2009.

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009, 113, 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hratchian H. P.; Bernhard Schlegel H. Accurate Reaction Paths Using a Hessian Based Predictor–corrector Integrator. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 9918–9924. 10.1063/1.1724823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem 2012, 33, 580–592. 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld F. L. Bonded-Atom Fragments for Describing Molecular Charge Densities. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1977, 44, 129–138. 10.1007/BF00549096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oláh J.; van Alsenoy C.; Sannigrahi A. B. Condensed Fukui functions derived from stockholder charges Assessment of their performance as local reactivity descriptors. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 3885–3890. 10.1021/jp014039h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.