Abstract

Spatial organization of the genome in the nucleus plays a critical role in development and regulation of transcription. A genomic region that resides at the nuclear periphery is part of the chromatin layer marked with histone H3 lysine 9 dimethyl (H3K9me2), but chromatin reorganization during cell differentiation can cause movement in and out of this nuclear compartment with patterns specific for individual cell fates. Here we describe a CRISPR-based system that allows visualization coupled with forced spatial relocalization of a target genomic locus in live cells. We demonstrate that a specified locus can be tethered to the nuclear periphery through direct binding to a dCas9-Lap2β fusion protein at the nuclear membrane, or via targeting of a histone methyltransferase (HMT), G9a fused to dCas9, that promotes H3K9me2 labeling and localization to the nuclear periphery. The enzymatic activity of the HMT is sufficient to promote this repositioning, while disruption of the catalytic activity abolishes the localization effect. We further demonstrate that dCas9-G9a-mediated localization to the nuclear periphery is independent of nuclear actin polymerization. Our data suggest a function for epigenetic histone modifying enzymes in spatial chromatin organization and provide a system for tracking and labeling targeted genomic regions in live cells.

Introduction

The three-dimensional organization of the genome within the eukaryotic nucleus plays a critical role in gene expression and cell identity (Peric-Hupkes and van Steensel, 2010; Phillips-Cremins et al., 2013; See et al., 2019). Chromatin is arranged and segregated into nuclear compartments to confer a level of gene regulation such that gene programs are initiated at the appropriate time and place during development (Meldi and Brickner, 2011; Stadhouders et al., 2019; Towbin et al., 2013). Differentiation involves relocation of some genes to the nuclear interior where they become activated while others are relocated to the nuclear periphery and expression is attenuated (Poleshko et al., 2017; Robson et al., 2016; See et al., 2019; Van de Vosse et al., 2011). Previous studies have described methods for manipulating the position of a genomic locus within the three-dimensional space of the nucleus. These studies primarily used a direct tethering approach to mediate the interaction of a locus and a protein that is itself fixed to a particular nuclear body through a chimeric protein intermediate (Finlan et al., 2008; Kumaran and Spector, 2008; Poleshko et al., 2017; Reddy and Singh, 2008; Reddy et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2018). Here, we show that epigenetic histone modification can lead to spatial repositioning.

Nuclear peripheral chromatin is uniquely marked by the Histone H3 Lysine 9 dimethyl (H3K9me2) modification (Poleshko et al., 2019). We asked if we could reposition a genomic locus to the periphery by modification with H3K9me2. Previous studies in C. elegans have established a role for histone methyltransferases (HMTs) to maintain interaction of chromatin with the nuclear lamina (Ahringer and Gasser, 2018; Gonzalez-Sandoval and Gasser, 2016). These include orthologues of mammalian G9a and GLP. Using the CRISPR-dCas9 system to direct G9a, an HMT “writer” of H3K9me2, to a target locus, we found that the locus was effectively repositioned to the nuclear periphery. Through a set of deletion and point mutations, we show that the HMT catalytic domain is necessary and sufficient for repositioning.

Long-range (>0.5 μm) movement of chromatin has been shown to be an active, ATP-dependent process (Dion and Gasser, 2013; Heun et al., 2001; Levi et al., 2005). Recent studies demonstrated a requirement for polymeric nuclear actin in this process (Zhang et al., 2020). In order to assess the possible involvement of nuclear actin in the mechanism underlying locus repositioning in our system, we examined the behavior of the target locus in cells that were treated with inhibitors of actin polymerization. We found no evidence of a requirement for nuclear actin under the assay conditions used in our study.

Results

dCas9-Lap2β and dCas9-G9a reposition a genomic locus to the nuclear periphery

We established a CRISPR-based system to monitor an individual genomic locus and manipulate its spatial position within the nucleus of a live cell. In order to target and visualize the locus of interest, we used a single sgRNA against a highly repetitive, gene-free, minimally transcribed region found on human chromosome 3 band 3q29 (Chr3q29) (Ma et al., 2016; Mele et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). Along with this sgRNA, we co-transfected human HEK293T cells with dCas9-SunTag and sfGFP-NLS constructs (Fig. 1A) described previously (Tanenbaum et al., 2014). This system allows visualization of targeted endogenous Chr3q29 loci in live cells (Fig. 1B). We assessed the position of the target loci relative to the nuclear periphery by co-transfecting constructs Chr3q29 sgRNA/dCas9-SunTag/sfGFP-NLS (labeled as control) and Lamin B1-mCherry to highlight the nuclear lamina and mark the nuclear periphery (Fig. 1B).

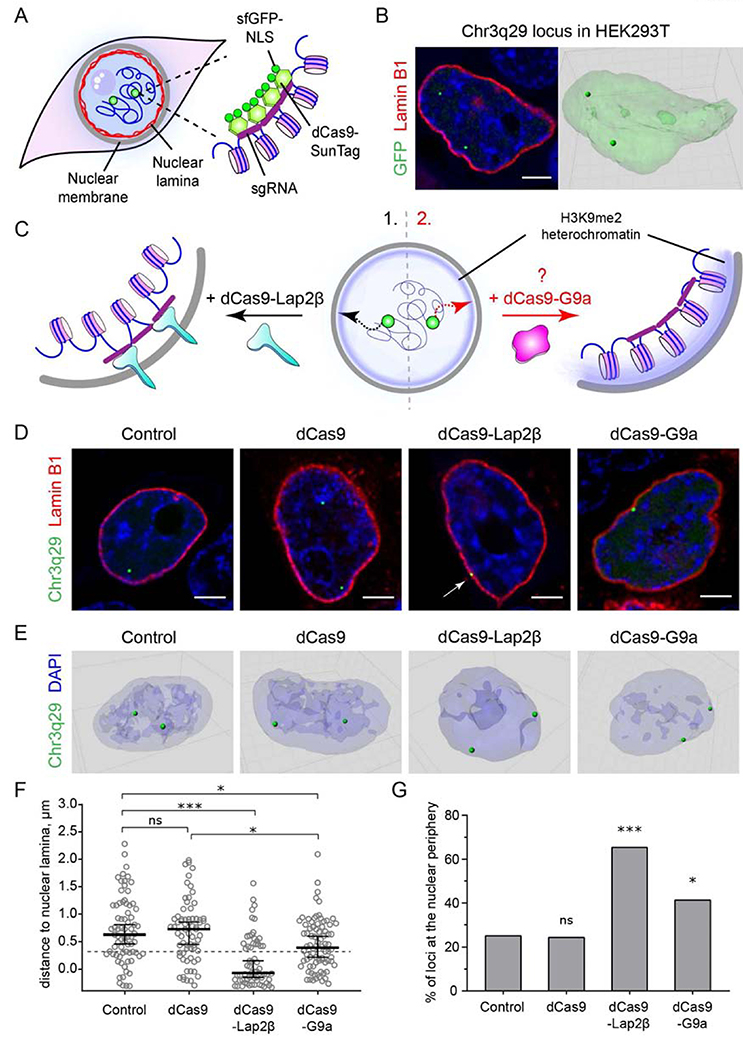

Figure 1. CRISPR-mediated relocalization of a targeted locus to the nuclear periphery.

(A) Schematic model of visualization of the target genomic locus with dCas9-SunTag/sfGFP in live cells. (B) Representative confocal and 3D-reconstructed images of HEK293T cells showing positions of Chr3q23 loci with dCas9-SunTag/sfGFP (green) and Lamin B1-mCherry (red). (C) Schematic depiction of the repositioning of target genomic regions to the nuclear periphery through 1) Lap2β tethering; 2) HMT addition. (D) Representative confocal images of live HEK293T cells transfected with indicated constructs, visualization cassette and Lamin B1-mCherry. (E) Representative 3D image reconstructions of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated constructs as in D. (F) Dot plot shows distribution of distances to the nuclear periphery (as defined by Lamin B1) of Chr3q29 loci in cells transfected with indicated constructs (median ± 95% confidence intervals). Dashed line indicates nuclear peripheral zone. (G) Box plot shows percentage of loci at the nuclear periphery. n≥25 cells per condition. Statistical analyses performed using One-way ANOVA test with multiple comparisons and Fisher exact test versus the control sample; *** p<0.001, * p<0.05, ns: not significant. Scale bars: 4μm.

Next, we expressed dCas9 fused to a nuclear integral membrane protein, Lamina-associated polypeptide 2 (Lap2β) to determine if we could reposition a locus to the nuclear periphery. Lap2β resides in the inner nuclear membrane (INM) where it binds the lamina network (Furukawa et al., 1995). We co-transfected HEK293T cells with constructs expressing the dCas9-Lap2β fusion, the visualization dCas9-SunTag/sfGFP-NLS cassette, and sgRNA targeting repeats at the Chr3q29 locus (Fig. 1C). We then assessed whether Chr3q29 loci would be tethered to the nuclear periphery through interaction with dCas9-Lap2β.

We performed confocal imaging on live cells and rendered the images in 3D to measure the distance between each locus and the nearest Lamin B1 surface (see Methods) (Fig. 1D, E). We then quantified the distance between loci and the nuclear lamina across multiple replicates to determine the percentage of alleles at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 1F, G). We measured the thickness of the H3K9me2 layer in HEK293T cells to be ~0.3μm (indicated as a dashed line in Figure 1F) and scored loci within this distance as peripheral, while those farther away were scored as nucleoplasmic (Fig. 1G).

In control cells expressing only the visualization constructs, we found that only 25% of the endogenous Chr3q29 loci are at the nuclear periphery. Similarly, the majority of endogenous Chr3q29 loci are positioned more centrally in the nucleoplasm in cells transfected with a control dCas9 construct (Fig. 1F, G).

In this system, co-transfection with the dCas9-Lap2β fusion construct resulted in a significant reduction in the average distance between each observed Chr3q29 locus and the nuclear periphery as compared with that seen for control cells or those expressing the control dCas9 construct (Fig. 1F). Expression of dCas9-Lap2β also effectively increased the percentage of alleles at the nuclear periphery from 25% in control cells to 65% (Fig. 1G). These results indicate that the Chr3q29 locus can be repositioned from the nucleoplasm to the nuclear periphery through targeting to dCas9-Lap2β in live cells.

Locus-directed G9a expression results in repositioning

We next asked what effect targeting of an epigenetic regulatory enzyme to a specific genomic locus would have on its position in the nucleus (Fig. 1C, right panel). To do this, we created a dCas9 fusion with the histone methyltransferase, G9a (EHMT2), which specifically mono- and dimethylates Lysine 9 of histone H3 (H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, respectively) (Collins and Cheng, 2010). Again, we targeted the Chr3q29 locus with a single sgRNA but co-transfected HEK293T cells with the dCas9-G9a construct. In these cells, the distance between the targeted loci and the nuclear periphery was, on average, smaller than that seen in control cells and similar to results seen with the dCas9-Lap2β fusion (Fig. 1F). Likewise, the dCas9-G9a transfected cell population showed a significant increase in the percentage of loci at the nuclear periphery as compared to untransfected cells or those expressing the dCas9 control construct (Fig. 1G). We conclude that CRISPR-mediated relocalization of a target locus can be achieved through expression of the HMT, G9a.

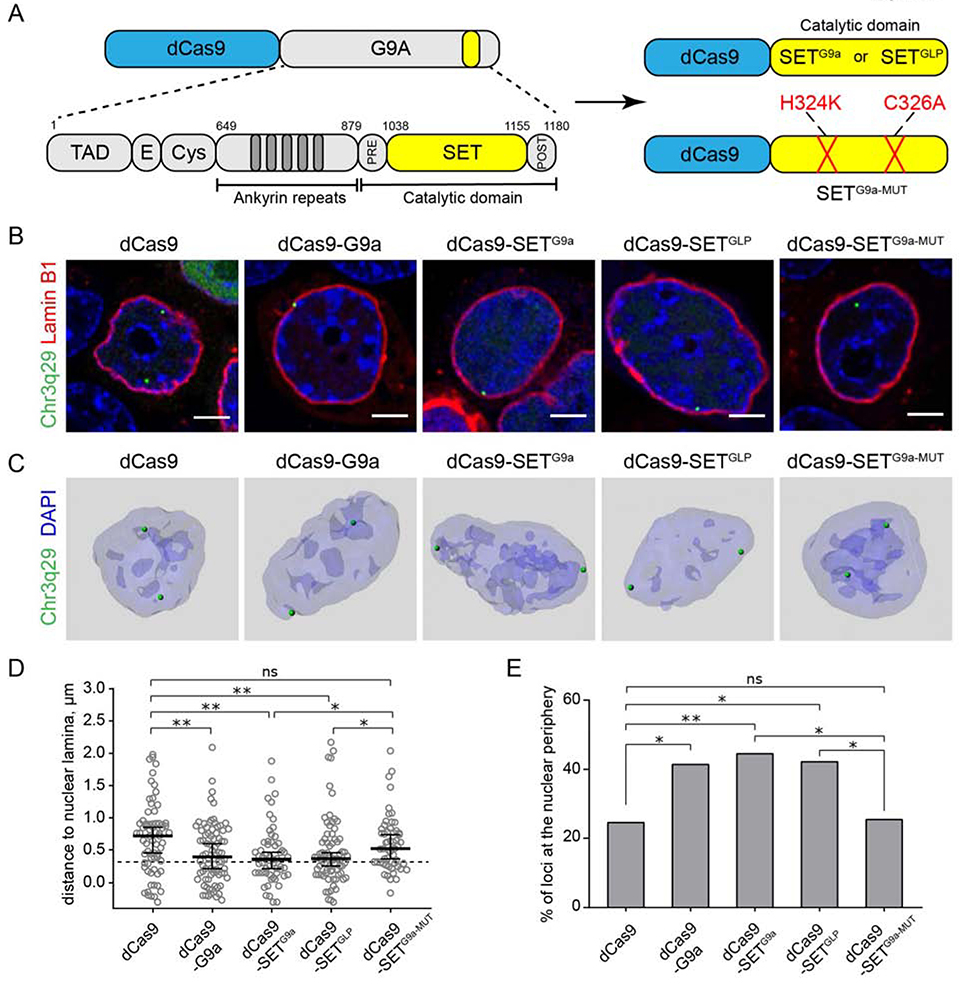

Lysine methyltransferase activity is necessary and sufficient to position a locus at the nuclear periphery

In order to determine the mechanism by which dCas9-G9a affects the nuclear position of a genomic locus, we examined the sufficiency of the catalytic HMT domain of G9a to alter spatial localization. In the context of the dCas9 fusion, we replaced the G9a coding sequence with that of the catalytic SET domain of G9a to create dCas9-SETG9a (Fig. 2A). Using our CRISPR-mediated targeting system, we examined the position of Chr3q29 loci in cells that were transfected with dCas9-SETG9a (Fig. 2B, C). Similar to results observed with the longer G9a isoform fused to dCas9, the dCas9-SETG9a-transfected cells had more Chr3q29 loci in close proximity to the nuclear periphery than control cells (Fig. 2D). We also tested the sufficiency of the SET domain of the G9a paralog GLP in this assay. GLP is another H3K9-specific HMT (Dillon et al., 2005), and SETGLP fused to dCas9 (dCas9-SETGLP) was also effective in repositioning the Chr3q29 loci to the nuclear periphery (Fig. 2D, E).

Figure 2. Lysine methyltransferase activity is necessary and sufficient to position a locus at the nuclear periphery.

(A) Schematic of the G9a-dCas9 fusion construct with known G9a protein domains G9a indicated below; dCas9-G9a SET domain fusion constructs: WT (SETG9a) and catalytic-dead mutant (SETG9a-MUT). (B) Representative confocal images of live HEK293T cells transfected with indicated constructs, visualization cassette and Lamin B1-mCherry. (C) Representative 3D image reconstructions of HEK293T cells transfected with indicated constructs as in B. (D) Dot plot shows distribution of distances to the nuclear periphery (as defined by Lamin B1) of Chr3q29 loci in cells transfected with indicated constructs (median ± 95% confidence intervals). Dashed line indicates nuclear peripheral zone. (E) Box plot shows percentage of loci at the nuclear periphery. n≥25 cells per condition. Statistical analyses performed using One-way ANOVA test with multiple comparisons and Fisher exact test; ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, ns: not significant. Scale bars: 4μm.

To test directly for the necessity of catalytic methyltransferase activity, we introduced two point mutations into the G9a SET domain that abolish HMT activity by converting residues 324 from H to K and 326 from C to A (dCas9-SETG9a-MUT), as described previously by Snowden et al. (Fig 2A) (Snowden et al., 2002). In cells transfected with dCas9-SETG9a-MUT, the targeted locus was not observed to be relocated to the nuclear periphery more than in control. The average distance of the Chr3q29 loci and the percentage of Chr3q29 loci at the nuclear periphery were both similar to those observed in control cells (Fig. 2D, E). This result demonstrates a requirement for HMT activity to reposition a genomic locus from the nuclear interior to the periphery in our system.

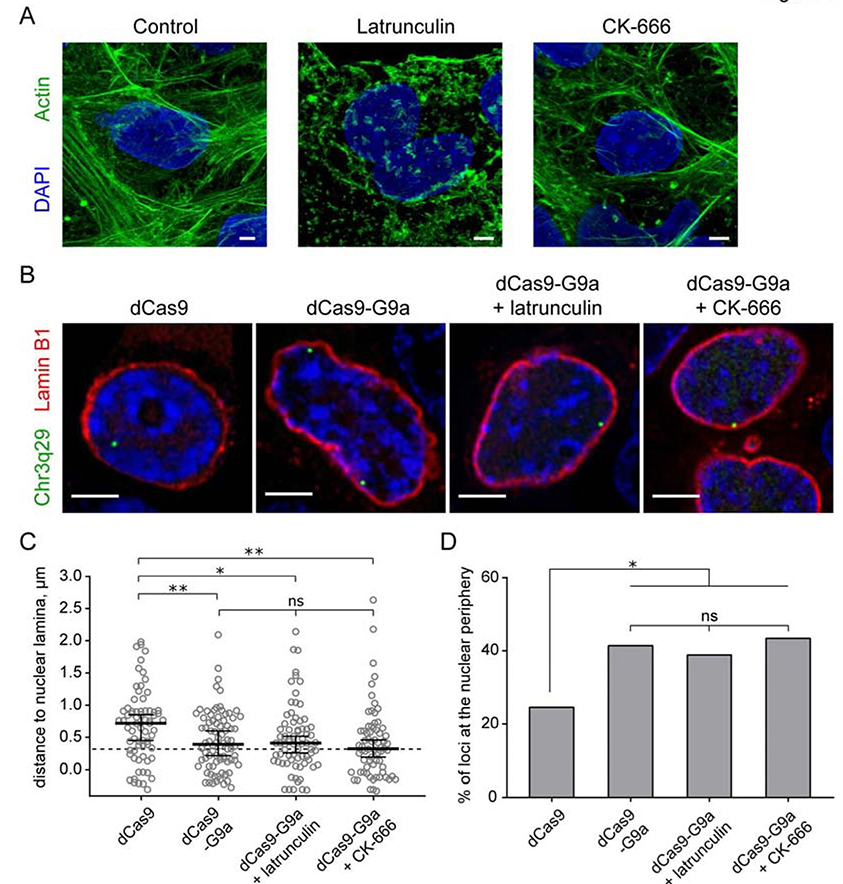

Nuclear actin polymerization is not required to reposition a locus to the nuclear periphery

Recent studies have revealed a role for nuclear actin in chromatin movement and remodeling (Hurst et al., 2019; Klages-Mundt et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). In order to determine whether nuclear actin is involved in repositioning a dCas9-targeted locus, we transfected cells with the dCas9-G9a fusion construct in the presence and absence of actin inhibitors and assayed the position of Chr3q29 loci. We tested two different chemicals: Latrunculin A, which binds monomeric actin to block actin polymerization (Coue et al., 1987), and CK-666 (Bolger-Munro et al., 2019), a small molecule inhibitor that binds Arp2/3 complex to prevent actin nucleation (Hetrick et al., 2013; van der Kammen et al., 2017). Although the effects of Latrunculin A on actin were obvious (Fig. 3A), we observed no apparent effect on repositioning in the presence of either inhibitor (Fig. 3B, C). The average distance of the targeted loci to the nuclear periphery and the number of loci at the nuclear periphery in dCas9-G9a cells treated with Latrunculin A was not significantly different compared with untreated cells (Fig. 3C, D). Similarly, when dCas9-G9a-transfected cells were treated with the small molecule inhibitor CK-666, targeted Chr3q29 loci were efficiently positioned at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 3C, D).

Figure 3. Nuclear actin polymerization is not required for repositioning a locus to the nuclear periphery.

(A) Representative confocal images of HEK293 cells treated with indicated inhibitors. Counterstained with DAPI (blue) and Phalloidin (green). (B) Representative confocal images of live HEK293T cells transfected with dCas9 or dCas9-G9a constructs and treated with nuclear actin polymerization inhibitors as indicated. Chr3q29 loci visualized with dCas9-SunTag/sfGFP (green). Co-transfected with Lamin B1-mCherry (red) and counterstained with Hoechst. (C) Dot plot shows distribution of distances to the nuclear periphery (as defined by Lamin B1) of Chr3q29 loci in cells transfected with indicated constructs (median ± 95% confidence intervals). Dashed line indicates nuclear peripheral zone. (D) Box plot shows percentage of loci at the nuclear periphery. n≥25 cells per condition. Statistical analyses performed using One-way ANOVA test with multiple comparisons and Fisher exact test; ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, ns: not significant. Scale bars: 4μm.

Discussion

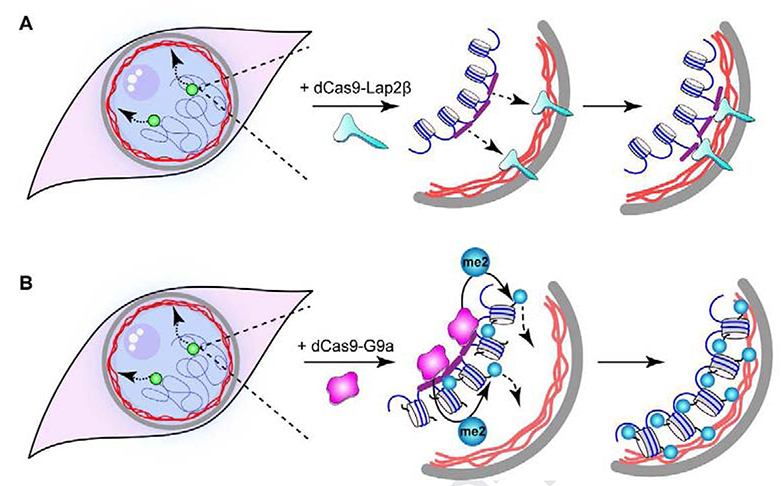

The results of this study illustrate the feasibility of manipulating three-dimensional organization of chromatin in the nucleus through epigenetic modification of a selected locus. We first demonstrated the function of the CRISPR-dCas9 system in repositioning a genomic locus from the nuclear interior to the periphery by effectively tethering it to a nuclear membrane protein, Lap2β (Fig. 4A). A similar methodology was previously used to relocate genomic loci to various distinct nuclear compartments using dCas9 fusions with proteins that reside in each of the respective compartments (Wang et al., 2018). The fusion of dCas9 with an inner nuclear envelope protein – Emerin in the previous study, or Lap2β in the current study – provides an anchor for the target locus at the nuclear membrane. We have expanded this system beyond protein-mediated physical tethering and successfully repositioned a genomic locus by directing an epigenetic enzyme to that locus. We show that the H3K9-targeted histone methyltransferase activity of G9a is sufficient to reposition a chosen locus to the nuclear periphery (Fig. 4B). Two epigenetic modifying proteins, G9a and GLP, contribute to H3K9me2 histone modification. Minimal constructs with dCas9 fused to the catalytic SET domain of either of these mammalian H3K9me2 HMTs, G9a or GLP, were effective in producing a change in position of the target locus within the nucleus. By expressing a methyltransferase-defective G9a mutant, we showed that the catalytic activity is required for the observed chromatin reorganization. Since both G9a and GLP mono- and dimethylate histone H3 at Lys9 (H3K9me1, H3K9me2), and H3K9me2 is the only modification known to be exclusively associated with nuclear peripheral chromatin (Poleshko et al., 2019), these results are consistent with a model in which increased H3K9me2 promotes the positioning of a locus to the nuclear periphery.

Figure 4. Model and Summary.

A schematic representation of directed tethering of a target genomic locus to the nuclear periphery via (A) dCas9-Lap2β fusion protein and direct DNA anchoring to the inner nuclear membrane; or (B) HMT activity directed through the dCas9-G9a fusion protein, and subsequent localization of the H3K9me2-marked chromatin locus to the nuclear periphery.

The precise position of a targeted locus depends on the method used to achieve its relocalization. The integral membrane protein, Lap2β, provides an anchor that is deeply embedded in the nuclear membrane, and thus the distance of a directly tethered locus to the edge of the nucleus is expected to be very small. The relocation of a locus when promoted by directed HMT activity is expected to result in positioning of the target locus adjacent to the inner nuclear lamina. Indeed, this is what we observed (compare dCas9-Lap2β, dCas9-G9a in Fig. 1F). This is also consistent with our observation that H3K9me2-modified chromatin forms a ~0.3mm layer inside the nuclear periphery (Poleshko et al., 2017). It would be of interest to compare the differences in accessibility and transcriptional activity of a locus embedded in the membrane versus one residing in the H3K9me2 chromatin layer.

Another potential benefit of studying a genetic locus that has been repositioned via histone modification is that, unlike a locus that is physically tethered to a membrane-bound protein (Reddy and Singh, 2008; Wang et al., 2018), epigenetic modification allows for an assessment of gene expression changes and further histone modification or nucleosome remodeling without possible artifactual interference (e.g. steric hindrance) of the tethering protein itself. The interaction of the histone methyltransferase with the target locus would presumably be transient and allow for the newly H3K9me2-modified locus to interact in native complexes with putative dimethyl readers at the nuclear periphery.

One can imagine the usefulness of such a system in which the position or accessibility of the locus might be further modified through targeted action of another epigenetic enzyme such as a histone demethylase (KDM) or histone deacetylase (HDAC). Such control would allow for investigation into the functional effect of epigenetic modifications at a target locus in a live cell. In previous studies, enzyme inhibitors were used to assess the impact of altered histone modifications on genome organization (Ahmed et al., 2010; Finlan et al., 2008; Muck et al., 2012; Shachar and Misteli, 2017), but these changes have broad, genome-wide effects. The methodology presented here illustrates the possibility for locus-specific studies. This system also facilitates the study of possible consequences of the “spreading” of histone post-translational marks (Al-Sady et al., 2013; Brickner et al., 2012; Grewal and Jia, 2007; Wang et al., 2014) into nearby regions as well as an assessment of which regions are vulnerable to encroachment of neighboring marks. This methodology expands our ability to probe nuclear architecture at a finer scale than has previously been possible and enables the detailed examination of epigenetic regulatory enzymes in mediating cellular phenotype through changes in 3D genome organization. In summary, this study demonstrates that epigenetic chromatin modification by histone methyltransferase activity can modulate nuclear architecture and the position of a specific genomic within the cell nucleus.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, cat# CRL-3216) and was routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination throughout the experimental procedures. HEK293T cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM (cat# 10–017-CV, Corning, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat# S11150, Atlanta Biologicals, GA), 1× penicillin-streptomycin, and 1× sodium pyruvate (cat# 30–002-CI and cat# 25–000-CI, Corning, NY).

Cloning

The original pHR-SFFV-dCas9-BFP-KRAB plasmid (Addgene #46911; pHR-SFFV-dCas9-BFP-KRAB was a gift from Stanley Qi & Jonathan Weissman (Gilbert et al., 2013)) was modified to remove the KRAB domain and to replace BFP with a V2A-mCherry reporter (amplified from p3E-mCherry, Addgene #108884; was a gift from a gift from Rob Parton (Ariotti et al., 2018)) to generate the base entry plasmid (pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-V2A-mCherry-WPRE). A BamHI single cut site was added upstream of V2A-mCherry sequence to facilitate cloning of fusion domains. Full-length rat Lap2β (250–1603 bp of NM_012887.1) was amplified from pEGFP-Lap2b (cat# P30463, Euroscarf; (Beaudouin et al., 2002)) with homology arms and inserted in frame into BamHI-linearized dCas9 plasmid using In-Fusion cloning (Takara Bio Inc. USA, CA) to generate dCas9-Lap2β. Human G9a (886–3651 bp of NM_006709.5) and minimal G9a histone methyltransferase domain (G9a SET) (2506–3651 bp of NM_006709.5) were amplified from MSCVhygro-F-G9a (Addgene #41721; MSCVhygro-F-G9a was a gift from Kai Ge (Wang et al., 2013)) and inserted in frame into BamHI-linearized dCas9 plasmid via In-Fusion cloning (Takara Bio USA, Inc., CA) to generate dCas9-G9a and dCas9-SETG9a, respectively. The G9a SET sequence was selected based on the work published by Snowden et al. (Snowden et al., 2002). Similar to the G9a SET sequence, human GLP SET domain (2737–3918 bp of NM_024757.5) was amplified from HEK293T genomic DNA and cloned into TOPO blunt vector (Zero Blunt™ TOPO™ PCR Cloning Kit, Invitrogen, MA) for verification of sequence identity by Sanger sequencing before subcloning into dCas9 plasmid via In-Fusion to generate dCas9-SETGLP construct. The point mutations (H324K, C326A) in G9a SET domain were generated using QuikChange II (Agilent Technologies, CA) and verified by Sanger sequencing, before subcloning into dCas9 plasmid to generate dCas9-SETG9a-MUT. sgRNA for Chr3q29 (Chr3: 195199022–195233876, hg19) was cloned into pKLV-U6 gRNA(BbsI)-PGK-puro-2A-BFP (Addgene #50946; pKLV-U6gRNA(BbsI)-PGKpuro2ABFP was a gift from Kosuke Yusa (Koike-Yusa et al., 2014)) using phosphorylated and annealed oligonucleotides via BbsI sites. sgRNA sequence for Chr3q29 (TGATATCACAG) was previously described by Ma et al., 2016 and Wang et al., 2018 (Ma et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018).

Transfection and inhibitors

In order to visualize the location of Chr3q29 locus in HEK293T cells, about 100000 cells were plated onto 35mm glass bottom culture dishes (cat# P35G-1.5–14-C, MatTek Corp., MA). Next day cells were transfected with sgRNA, dCas9-SunTag (Addgene #60910; pHRdSV40-NLS-dCas9–24×GCN4_v4-NLS-P2A-BFP-dWPRE was a gift from Ron Vale (Tanenbaum et al., 2014)), scFV-sfGFP-NLS (Addgene # 60906), dCas9-Fusion, and Lamin B1-mCherry (Addgene # 55069; mCherry-LaminB1–10 was a gift from Michael Davidson) constructs. All plasmid transfections were prepared in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (cat# 31985062, Gibco, MD) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (cat# 11668027, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA). The dCas9-tethering fusion plasmids (dCas9-Lap2b, dCas9-G9a etc.) were transfected at 10 μg, while dCas9-SunTag, scFV-sfGFP-NLS and Lamin B1-mCherry were transfected at 1 μg each. We performed a set of titration experiments using 1:1, 5:1 and 10:1 plasmid concentration ratio and found that 10:1 ratio (dCas9-Tethering fusion and dCas9-SunTag, respectively) is the most efficient combination. It allows efficient visualization of the targeted genomic region in live cells as well as repositioning to the nuclear periphery. We found this plasmid ratio to be optimal in our system, but we believe that a new titration should be performed if different cell type, plasmid constructs or transfection protocol are used. For the experiments with inhibitors, transfections with the corresponding plasmids were done in parallel with the addition of 200 nM Latrunculin A (cat# 248026, Sigma-Millipore, MA) or 100 μM CK-666 (cat# SML0006, Sigma-Millipore, MA).

Live cell imaging and image analysis

Prior to imaging, cells were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 Solution (cat# 62249, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) in order to visualize the DNA in the nucleus. Confocal imaging was performed at 48 hours post-transfection or incubation with the inhibitors using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LEICA 3× STED, University of Pennsylvania Cell and Developmental Biology Core). The images were taken using 0.15 μm step Z stacks, with a minimum range of 50 to 100 Z-planes per image. Images were deconvoluted using Huygens Professional software (Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., Netherlands). In order to quantify the distance between the genomic locus visualized with gRNA/SunTag/dCas9 and the nuclear lamina (LaminB1-mCherry), 3D reconstructions were created using IMARIS 9 software (Bitplane AG, Switzerland). Nuclear lamina, Chr3q29 loci, and nuclei surfaces were created based on the fluorescent signals from the LaminB1-mCherry, SunTag/dCas9, and Hoechst using the Surfaces and Dots tools, respectively. Distance from the center of the dots to the edge of the nuclear lamina surface was quantified using the Distance Transformation tool. For each experimental condition, 25 to 35 cells were imaged with a total of more than 55 loci per condition. In cases when the signal from a dot was imbedded into the nuclear lamina layer, the measurement returned negative distances. If the distance from the dot to nuclear lamina was smaller than 0.3 μm (average thickness of the peripheral heterochromatin measured as described previously (Poleshko et al., 2017), then the dot was counted as localized to the nuclear periphery.

Fixed cell imaging

HEK293T cells were cultured on coverslips treated with Laminin (cat# 354232, Corning, NY) according to the manufacturer recommendation. After 48 hours of treatment with the inhibitors cells were fixed with 2% PFA (cat# 15710, Electron Microscopy Sciences, PA) in DPBS (cat# 14040, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) for 10 min at room temp and washed with DPBS 3 times for 5 min. Then cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 (cat# 28314, ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) in DPBS for 10 min at room temperature. To visualize actin filaments cells were stained with phalloidin-568 (cat# A12380, Invitrogen/ThermoFisher Scientific, MA) for 40 min according to the manufacturer recommendation and counterstained with DAPI (cat# DUO82040–5ML, Sigma-Millipore, MA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad PRISM 8.0.1 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.) using ANOVA One-way non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis test) corrected for multiple comparisons by controlling the False Discovery Rate or Fisher Exact test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns: not significant.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| Reagent or resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Invitrogen/ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 11668027 |

| Laminin, Mouse | Corning | Cat# 354232 |

| Alexa Fluor™-568 Phalloidin | Invitrogen/ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A12380 |

| Hoechst 33342 Solution | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 62249 |

| Mounting Medium with DAPI | Sigma-Millipore | Cat# DUO82040–5ML |

| Latrunculin A | Sigma-Millipore | Cat# 428026; CAS 76343–93-6 |

| CK-666 | Sigma-Millipore | Cat# SML0006; CAS: 442633–00-3 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| In-Fusion® HD Cloning Plus kit | Takara Bio USA, Inc. | Cat# 638911 |

| QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 200523 |

| Zero Blunt™ TOPO™ PCR Cloning Kit | Invitrogen/ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 450245 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-3216; RRID: CVCL_0063 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| PCR/cloning Primer V2A-mCherry FW: AGCAACGGCAGCAGCGGATCCGGTTCCGGAGCCACGAAC | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer V2A-mCherry RV: TCGACTCTAGTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer WPRE FW: TGTACAAGTACTAGAGTCGACCTGCAGGC | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer WPRE RV: ATACACGGAATTAATTCTAGATGCTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer Lap2β FW: CGGCAGCAGCGGATCGATGCCGGAGTTCCTAGAG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer Lap2β RV: CTCCGGAACCGGATCCGTTGGATATTTTAGTATCTTGAAG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer G9a FW: CGGCAGCAGCGGATCGTCTGAAGTTGAAGCTCTAACTG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer G9a RV: CTCCGGAACCGGATCCTGTGTTGACAGGGGGCAG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETG9a FW: CGGCAGCAGCGGATCGGGCAGCGCCGCCATCGC | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETG9a RV: CTCCGGAACCGGATCCTGTGTTGACAGGGGGCAGG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETGLP FW (to subclone into TOPO-pCRII): CGAGACAACGAGGAGAACATTT | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETGLP RV (to subclone into TOPO-pCRII): ATCTCTCCTCCTCGTCCTCTAA | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETGLP FW (to subclone into base entry plasmid): CGGCAGCAGCGGATCGGAGGAGAACATTTGCCTGCAC | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer SETGLP RV (to subclone into base entry plasmid): CTCCGGAACCGGATCCTAGGGGGTCGGCGGCAG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer Quick Change-SETG9a-MUT FW: ACATCAGCCGCTTCATCAACAAACTGGCTGACCCCAACATCATTCCCG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR/cloning Primer Quick Change-SETG9a-MUT RV: CGGGAATGATGTTGGGGTCAGCCAGTTTGTTGATGAAGCGGCTGATGT | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer dCas9 FW (for the base entry vector): ATCATCCACCTGTTTACCCTGAC | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer mCherry RV (for the base entry vector): TGAACTGAGGGGACAGGATGT | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer G9a FW: GAGTCAGAGAGGCGGAAGAAG | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer G9a FW_2: CACCACGCAGCCAAAATC | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer G9a FW_3: GTATGACAAGGATGGGCGATT | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer G9a RV: CCGTCCTCCTCCTTGCTAT | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer SETG9a-MUT FW: TCGTACAGAGTGGCATCAAG | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer SETG9a-MUT RV: CAATGGCTTCGGCTGAGT | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer pKLV FW (for sgChr3): GAAGGTGGAGAGAGAGACAGAGAC | This paper | N/A |

| Sequencing Primer PGK RV (for sgChr3): TACCGGTGGATGTGGAATGT | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Human G9a: MSCVhygro-F-G9a | Wang et al., 2012 | Addgene Plasmid #41721; RRID: Addgene_41721 |

| Human Lamin B1: mCherry-LaminB1–10 | Davidson lab (unpublished) | Addgene Plasmid #55069; RRID: Addgene_55069 |

| SunTag system: pHRdSV40-NLS-dCas9–24×GCN4_v4-NLS-P2A-BFP-dWPRE | Tanenbaum et al., 2014 | Addgene Plasmid #60910; RRID: Addgene_60910 |

| SunTag system: pHR-scFv-GCN4-sfGFP-GB1-NLS-dWPRE | Tanenbaum et al., 2014 | Addgene Plasmid #60906; RRID: Addgene_60906 |

| Rat Lap2β: pEGFP-Lap2b | Beaudouin et al., 2002 | Euroscarf Plasmid, #P30463 |

| Empty sgRNA expressing vector: pKLV-U6gRNA(BbsI)-PGKpuro2ABFP | Koike-Yusa et al., 2014 | Addgene Plasmid #50946; RRID: Addgene_50946 |

| To replace BFP-KRAB-WPRE: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-BFP-KRAB (for the base entry vector) | Gilbert et al., 2013 | Addgene Plasmid #46911; RRID: Addgene_46911 |

| To insert V2A-mCherry-WPRE: p3E-mCherry (for the base entry vector) | Ariotti et al., 2018 | Addgene Plasmid #108884; RRID: Addgene_108884 |

| Base entry vector: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| dCas9-Lap2β: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-Lap2β-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| dCas9-G9a: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-G9a FL-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| dCas9-SETG9a: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-SETG9a-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| dCas9-SETG9a-MUT: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-SETG9a-MUT-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| SETGLP: TOPO-pCRII-GLP SET | This paper | N/A |

| dCas9-SETGLP: pHR-SFFV-dCas9-HA-SETGLP-V2A-mCherry-WPRE | This paper | N/A |

| Chr3 sgRNA: pKLV-U6gRNA(Chr3)-PGKpuro2ABFP | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| IMARIS 9 | Bitplane AG, Switzerland | https://imaris.oxinst.com/; RRID: SCR_007370 |

| Huygens Professional software | Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., Netherlands | https://svi.nl/Huygens-Software; RRID: SCR_014237 |

| GraphPad PRISM 8.0.1 | GraphPad Software, Inc., CA | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/; RRID: SCR_002798 |

| Other | ||

CRISPR-dCas9 system spatially repositions genomic loci to the nuclear periphery

Histone methyltransferase activity is necessary and sufficient to relocate a locus

Locus-directed H3K9me2 modification results in nuclear peripheral localization

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Stout from the Penn CDB Microscopy Core for help with imaging. This work was supported by NIH (R35 HL140018 to J.A.E.), the Cotswold Foundation (to J.A.E.), the WW Smith endowed chair (to J.A.E.), and the NSF (CMMI-1548571 to J.A.E.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ahmed S, Brickner DG, Light WH, Cajigas I, McDonough M, Froyshteter AB, Volpe T, Brickner JH, 2010. DNA zip codes control an ancient mechanism for gene targeting to the nuclear periphery. Nat Cell Biol 12, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahringer J, Gasser SM, 2018. Repressive Chromatin in Caenorhabditis elegans: Establishment, Composition, and Function. Genetics 208, 491–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sady B, Madhani HD, Narlikar GJ, 2013. Division of labor between the chromodomains of HP1 and Suv39 methylase enables coordination of heterochromatin spread. Mol Cell 51, 80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariotti N, Rae J, Giles N, Martel N, Sierecki E, Gambin Y, Hall TE, Parton RG, 2018. Ultrastructural localisation of protein interactions using conditionally stable nanobodies. Plos Biology 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudouin J, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Eils R, Ellenberg J, 2002. Nuclear envelope breakdown proceeds by microtubule-induced tearing of the lamina. Cell 108, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger-Munro M, Choi K, Scurll JM, Abraham L, Chappell RS, Sheen D, Dang-Lawson M, Wu X, Priatel JJ, Coombs D, Hammer JA, Gold MR, 2019. Arp2/3 complex-driven spatial patterning of the BCR enhances immune synapse formation, BCR signaling and B cell activation. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Ahmed S, Meldi L, Thompson A, Light W, Young M, Hickman TL, Chu F, Fabre E, Brickner JH, 2012. Transcription factor binding to a DNA zip code controls interchromosomal clustering at the nuclear periphery. Dev Cell 22, 1234–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Cheng X, 2010. A case study in cross-talk: the histone lysine methyltransferases G9a and GLP. Nucleic Acids Res 38, 3503–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coue M, Brenner SL, Spector I, Korn ED, 1987. Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Lett 213, 316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng X, 2005. The SET-domain protein superfamily: protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol 6, 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion V, Gasser SM, 2013. Chromatin movement in the maintenance of genome stability. Cell 152, 1355–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, Ylstra B, Chubb JR, Bickmore WA, 2008. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet 4, e1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Pante N, Aebi U, Gerace L, 1995. Cloning of a cDNA for lamina-associated polypeptide 2 (LAP2) and identification of regions that specify targeting to the nuclear envelope. Embo j 14, 1626–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar GA, Torres SE, Stern-Ginossar N, Brandman O, Whitehead EH, Doudna JA, Lim WA, Weissman JS, Qi LS, 2013. CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Gasser SM, 2016. Mechanism of chromatin segregation to the nuclear periphery in C. elegans embryos. Worm 5, e1190900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, Jia S, 2007. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat Rev Genet 8, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick B, Han MS, Helgeson LA, Nolen BJ, 2013. Small molecules CK-666 and CK-869 inhibit actin-related protein 2/3 complex by blocking an activating conformational change. Chem Biol 20, 701–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun P, Laroche T, Shimada K, Furrer P, Gasser SM, 2001. Chromosome dynamics in the yeast interphase nucleus. Science 294, 2181–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst V, Shimada K, Gasser SM, 2019. Nuclear Actin and Actin-Binding Proteins in DNA Repair. Trends Cell Biol 29, 462–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klages-Mundt NL, Kumar A, Zhang Y, Kapoor P, Shen X, 2018. The Nature of Actin-Family Proteins in Chromatin-Modifying Complexes. Front Genet 9, 398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike-Yusa H, Li Y, Tan EP, Velasco-Herrera Mdel C, Yusa K, 2014. Genome-wide recessive genetic screening in mammalian cells with a lentiviral CRISPR-guide RNA library. Nat Biotechnol 32, 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran RI, Spector DL, 2008. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol 180, 51–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi V, Ruan Q, Plutz M, Belmont AS, Gratton E, 2005. Chromatin dynamics in interphase cells revealed by tracking in a two-photon excitation microscope. Biophys J 89, 4275–4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Tu LC, Naseri A, Huisman M, Zhang S, Grunwald D, Pederson T, 2016. Multiplexed labeling of genomic loci with dCas9 and engineered sgRNAs using CRISPRainbow. Nat Biotechnol 34, 528–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldi L, Brickner JH, 2011. Compartmentalization of the nucleus. Trends Cell Biol 21, 701–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele M, Ferreira PG, Reverter F, DeLuca DS, Monlong J, Sammeth M, Young TR, Goldmann JM, Pervouchine DD, Sullivan TJ, Johnson R, Segre AV, Djebali S, Niarchou A, Consortium GT, Wright FA, Lappalainen T, Calvo M, Getz G, Dermitzakis ET, Ardlie KG, Guigo R, 2015. Human genomics. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science 348, 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muck JS, Kandasamy K, Englmann A, Gunther M, Zink D, 2012. Perinuclear positioning of the inactive human cystic fibrosis gene depends on CTCF, A-type lamins and an active histone deacetylase. J Cell Biochem 113, 2607–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peric-Hupkes D, van Steensel B, 2010. Role of the nuclear lamina in genome organization and gene expression. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 75, 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Cremins JE, Sauria ME, Sanyal A, Gerasimova TI, Lajoie BR, Bell JS, Ong CT, Hookway TA, Guo C, Sun Y, Bland MJ, Wagstaff W, Dalton S, McDevitt TC, Sen R, Dekker J, Taylor J, Corces VG, 2013. Architectural protein subclasses shape 3D organization of genomes during lineage commitment. Cell 153, 1281–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshko A, Shah PP, Gupta M, Babu A, Morley MP, Manderfield LJ, Ifkovits JL, Calderon D, Aghajanian H, Sierra-Pagan JE, Sun Z, Wang Q, Li L, Dubois NC, Morrisey EE, Lazar MA, Smith CL, Epstein JA, Jain R, 2017. Genome-Nuclear Lamina Interactions Regulate Cardiac Stem Cell Lineage Restriction. Cell 171, 573–587 e514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshko A, Smith CL, Nguyen SC, Sivaramakrishnan P, Wong KG, Murray JI, Lakadamyali M, Joyce EF, Jain R, Epstein JA, 2019. H3K9me2 orchestrates inheritance of spatial positioning of peripheral heterochromatin through mitosis. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KL, Singh H, 2008. Using molecular tethering to analyze the role of nuclear compartmentalization in the regulation of mammalian gene activity. Methods 45, 242–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H, 2008. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature 452, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson MI, de Las Heras JI, Czapiewski R, Le Thanh P, Booth DG, Kelly DA, Webb S, Kerr ARW, Schirmer EC, 2016. Tissue-Specific Gene Repositioning by Muscle Nuclear Membrane Proteins Enhances Repression of Critical Developmental Genes during Myogenesis. Mol Cell 62, 834–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See K, Lan Y, Rhoades J, Jain R, Smith CL, Epstein JA, 2019. Lineage-specific reorganization of nuclear peripheral heterochromatin and H3K9me2 domains. Development 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shachar S, Misteli T, 2017. Causes and consequences of nuclear gene positioning. J Cell Sci 130, 1501–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden AW, Gregory PD, Case CC, Pabo CO, 2002. Gene-specific targeting of H3K9 methylation is sufficient for initiating repression in vivo. Curr Biol 12, 2159–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadhouders R, Filion GJ, Graf T, 2019. Transcription factors and 3D genome conformation in cell-fate decisions. Nature 569, 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum ME, Gilbert LA, Qi LS, Weissman JS, Vale RD, 2014. A protein-tagging system for signal amplification in gene expression and fluorescence imaging. Cell 159, 635–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin BD, Gonzalez-Sandoval A, Gasser SM, 2013. Mechanisms of heterochromatin subnuclear localization. Trends Biochem Sci 38, 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vosse DW, Wan Y, Wozniak RW, Aitchison JD, 2011. Role of the nuclear envelope in genome organization and gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 3, 147–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kammen R, Song JY, de Rink I, Janssen H, Madonna S, Scarponi C, Albanesi C, Brugman W, Innocenti M, 2017. Knockout of the Arp2/3 complex in epidermis causes a psoriasis-like disease hallmarked by hyperactivation of transcription factor Nrf2. Development 144, 4588–4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Xu X, Nguyen CM, Liu Y, Gao Y, Lin X, Daley T, Kipniss NH, La Russa M, Qi LS, 2018. CRISPR-Mediated Programmable 3D Genome Positioning and Nuclear Organization. Cell 175, 1405–1417.e1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lawry ST, Cohen AL, Jia S, 2014. Chromosome boundary elements and regulation of heterochromatin spreading. Cell Mol Life Sci 71, 4841–4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Xu S, Lee JE, Baldridge A, Grullon S, Peng W, Ge K, 2013. Histone H3K9 methyltransferase G9a represses PPARgamma expression and adipogenesis. EMBO J 32, 45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang Y, Lei Y, Wei Z, Li Y, Wang Y, Bu Y, Zhang C, 2020. Proline-rich 11 (PRR11) drives F-actin assembly by recruiting the actin-related protein 2/3 complex in human non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Biol Chem 295, 5335–5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]