Abstract

Introduction:

Female genital cutting is a practice that has incited controversy and conflicting discourses across the international community. There is a need to analyze social media data on the portrayal of the practice in order to gather insights and inform strategic planning and interventions design. This study aims to explore and describe the portrayal of female genital cutting in the comments section of YouTube comment posts.

Methods:

This mixed-method study employs a content analysis approach with a sequential exploratory design. A total of 150 YouTube comment posts were analyzed through qualitative content analysis and quantitative descriptive content analysis on NVivo 11 and Microsoft Excel, respectively.

Results:

Salient subthemes from the qualitative component included likening female genital cutting with male genital cutting, differentiating female genital cutting from male genital cutting, branding female genital cutting as a harmful and unethical practice, branding female genital cutting as a normal tradition, contribution of religion and culture to female genital cutting, gender inequality issues, and the need for education or cultural relativism to change or cope with the practice. The quantitative component identified neutral, positive, mixed, and neutral tones; and formal, colloquial, and mixed language types; as well as targets of stigma with patterns in the themes.

Conclusion:

The portrayal of female genital cutting in the YouTube comment posts revealed the range of perceptions, beliefs, and opinions of users with various stances on the practice. Study findings are useful for strategic planning and the development of interventions with informative goals. Study findings can also help to gage and evaluate the effectiveness of existing programs that aim to reduce misinformation about female genital cutting or aim to reduce stigmas surrounding the practice.

Keywords: content analysis, female genital cutting, social media analysis, YouTube comments

Introduction

Female genital cutting (FGC) is the partial or complete removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical purposes.1 There are four types of FGC: clitoridectomy (type 1), excision of the labia (type 2), infibulation (type 3), and other harmful non-medical practices, such as pricking, incising, and cauterization (type 4). Clitoridectomy entails the partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the clitoral hood.1 The partial or total removal of the labia minora alone, or the clitoris and labia minora, with or without the excision of the labia majora is referred to as excision. Infibulation, the most pervasive type of FGC, involves the suturing of the labia minora and/or the labia majora to create a covering seal that narrows the vaginal orifice.1 The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that over 200 million girls and women are currently living across the world having undergone FGC, mostly in African and Asian countries.2 FGC can lead to serious medical consequences, including maternal bleeding, infections, prolonged labor, and chronic pain, at different periods in the life course.3 In fact, genital alterations from each type of FGC are associated with increased obstetric complications, making it a significant indirect cause of maternal mortality and morbidity. FGC can also result in debilitating psychological and social consequences.4 In addition, both the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF officially recognize FGC as a violation of girls’ and women’s human rights, including their rights to health, security, and physical integrity.1,2 While FGC is illegal in most countries, its deep entrenchment in social, cultural, and economic practices along with the weak enforcement of anti-FGC laws helps to sustain the practice.

FGC is a vital cultural tradition and social norm in practicing communities. It can be part of a girl’s initiation rites and passage into womanhood, making it a crucial component of a woman’s cultural and gender identity.5 In addition, practicing communities deem FGC a requirement for preserving a female’s chastity, purity, modesty, and femininity.6 Conformity to this tradition is associated with higher marriage prospects for the female, economic and social security, and social acceptance for her family.7 Nonconformity not only lowers marriage prospects but may also be met with social exclusion, moral judgments, verbal bullying, and possible violence from the community.8 Some girls undergo FGC because they believe that the social stigma of promiscuity and lewdness is far more crippling to their lives than the potential health consequences associated with FGC.7,8 In areas where FGC is not a common practice, some opponents of FGC tend to brand FGC as a savage and primitive procedure that is performed by uncivilized and inferior people.9,10

Social media is the largest and richest collection of information about society today, providing dynamic views from around the world on a large variety of topics.11 It can have a powerful influence in shaping perceptions and community opinion on social norms and practices. Social media can also be used to gage the perceptions and opinions of the international community. The media coverage of FGC has a significant influence on discourse in various communities. A study on American and English news media found that media discourse frequently presented FGC as a practice that minimizes women’s sexual agency.12 Moreover, the news media portrayed it as a recurrent human rights and women’s health issue.13 FGC is also primarily framed as a barbaric practice bred from cultural rituals, with Western media discourse often pinpointing on non-Western cultures.14,15 Information on the practice of FGC, including interviews or testimonies from members of practicing communities, health education, anti-FGC campaigns, and news are found on various social media forums, such as YouTube. YouTube, a dynamic platform for multimedia information, has over 1 billion hours of video watch-time every day, and over 2 billion logged-in users every month.16 The platform ranks second overall in global Internet engagements—to Google.17 YouTube video content, video rating, and user comments have all been used in research to analyze user-generated actions, with a focus on themes in the videos or user comments.18 Researchers can use the platform to study the interaction between users in the comment sections to assess the emotional and socio-psychological features of user impressions on the videos or other comments. With more than 2 billion users, YouTube has a large user base from diverse demographic and cultural backgrounds, making it ideal for assessing a wide range of opinions and reflections on FGC.16 Although there have been studies that assessed the representation of FGC from the press, there is no study that has assessed the portrayal of FGC from users on social media platforms, including YouTube. In consort, this study aims to explore and describe how users reflect on and portray FGC in the comments section of YouTube posts. Identifying YouTube users’ perceptions, beliefs, and opinions helps to explore and describe the thematic patterns, as well as the writing styles within the themes. The type of content identified in the study, whether seen as constructive or destructive by the reader, can have vital implications for policy initiatives and interventions design and evaluation.

Methods

Study design

This study used a mixed-method content analysis approach with a sequential exploratory design.19 The sequential mixed-method exploratory design, which is feasible to implement and report, was selected because it has proven useful for exploring phenomena and expanding on qualitative findings with quantitative findings.19 Content analysis was selected because the research method has been increasingly useful for analyzing qualitative and quantitative data from written messages on media platforms.20,21 In this study, the qualitative component sought to explore the perceptions of YouTube users on FGC. The quantitative component sought to help explore the perceptions of FGC by quantifying and describing the tones, languages, and stigma around FGC from users. The authors complemented and expanded upon the main qualitative component with the quantitative component. The study assessed comments from the commenting facility, which is the most widely used communication feature on YouTube and one of the most popular commenting facilities on social media.18,22 Its character limit is among the largest from social media platforms, thereby enabling more thorough expressions of personal views about a given topic.23

Data collection

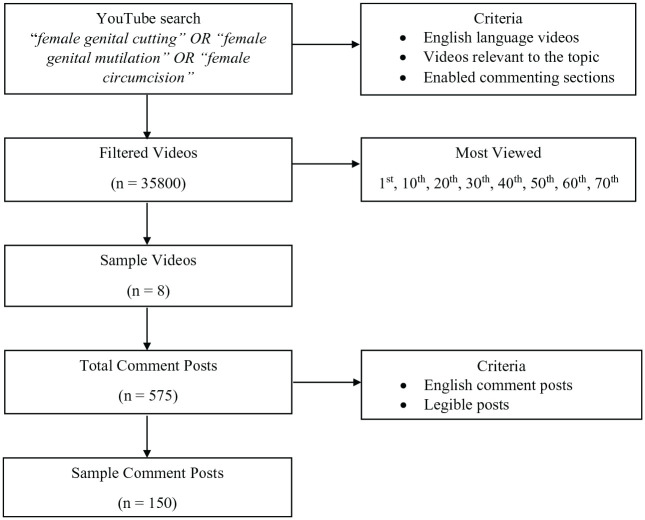

The search was conducted in January 2018 on the YouTube search engine, resulting in 35,800 videos; YouTube presented these videos in descending order based on view count (Figure 1). Given the small range in focus from the videos and the scope of the study in consideration, comment posts from eight videos were deemed adequate for this research. Search volume, publication value, attention cycles, features for content discovery (e.g. recommendations), subscriptions, and issue and platform vernaculars were factors that may have influenced video popularity and view count.24,25 In addition, controversial videos that feed on loyal audiences also tend to appear in top positions and get more views. To personalize content to individual users, YouTube’s algorithm personalizes and recommends videos based on viewership history, interactions on videos watched (likes, dislikes, comments, time spent), and videos watched by people who watch similar videos.26,27 As videos with less than 63,000 views (90+ most viewed videos) generally only had a few comments, the first author selected the 1st, 10th, 20th, 30th, 40th, 50th, 60th, and 70th most viewed videos through modified systematic random sampling with two starts.28,29 In the instance that the video was not relevant to FGC or had a disabled comment section, the following video that was relevant to FGC and with an enabled comment section was instead selected. The rationale for this sampling method was to account for a diverse range of users and explore multiple perspectives. The study also used randomization as a pragmatic and ethical strategy to minimize researcher bias, as well as to use a fair and transparent procedure when selecting videos and comment posts for future analysis. This further helped minimize researcher influence over the inclusion of certain eligible videos while excluding others.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of video selection process and comment post sampling process.

The videos, which were published between 2007 and 2017, stream content about FGC classifications, reasons for the continuation of the practice, adverse effects, experiences with being cut, and perceptions about FGC. Video 1 is an educational public service announcement about FGC (see Table 1). Video 2 is a Fox news debate between the host (Tucker Carlson) and an FGC advocate. Video 3 is a BBC studios documentary in Afar (Ethiopia) that interviews tribal wives about their experiences with FGC. Video 4 is a short documentary about FGC practices in Sierra Leona. Video 5 is an ABC news interview with an American woman who had underwent FGC and then turned into an anti-FGC activist. Video 6 is a Guardian report and video campaign to end the practice. Video 7 is a BBC news night report on FGC practices in Egypt. Video 8 is an interview in London (England) with girls about their FGC experiences.

Table 1.

Videos and comment posts.

| Videos | Total comment posts | Comment posts included in samplea |

|---|---|---|

| 1. “Female genital cutting” (1) | 116 | 30 |

| 2. “Don’t call it mutilation” Tucker can’t believe this female circumcisions advocate | 105 | 28 |

| 3. “Afar Tribe: circumcision—tribal wives” | 101 | 25 |

| 4. “Female genital cutting” (2) | 75 | 22 |

| 5. “American woman who underwent female genital mutilation comes forward to help others” | 62 | 16 |

| 6. “End female genital mutilation: join the guardian’s campaign” | 49 | 13 |

| 7. “Female genital mutilation in Egypt” | 38 | 8 |

| 8. “Female circumcision” | 29 | 8 |

| 575 | 150 |

The amount of sample comment posts from each video is proportional to the total comment posts and the total sample required, with 10 additional posts randomly selected from the remaining comment posts. The sample posts were selected through stratified systematic sampling; for instance, every fourth post was selected under video 1, while every third post was selected under video 3.

The comment sections from these eight videos, with over 5000 comment posts and replies, were imported into NVivo 11 as webpage pdfs using the Ncapture chrome plugin. The study excluded reply comments to the original comment posts made toward the video in order to enable the collection of data (opinions, reflections) about the video and its presented topic rather than the topic presented in the original comment post. Moreover, as the reply comments were mainly in response to the views of the popular posts, they were excluded to enable the collection of a representative variety of perceptions. Considering the richness of data in the comment posts, 140 sample comment posts were deemed sufficient for saturation. To check if any new themes would arise from the data, 10 additional comment posts were randomly selected from the remaining 435 comment posts and then coded during the analysis process. As shown in Table 1, the number of comment posts from the eight comment sections ranged from 29 to 116. This range called for a proportional selection of the comment posts from each comment section, using stratified systematic sampling.30 This sampling method was employed to minimize researcher bias in selecting sample comment posts. The method also ensured the collection of various types of posts, including the less popular (often without likes and replies) comment posts toward the end of the comment section scroll. The sampling method thereby reduced researcher influence over why certain eligible posts were included while others were excluded.

Data analysis

The first author (male graduate student) conducted a manual content analysis on NVivo 11. To ensure that the analysis process was methodical and transparent, this study followed the guide for conducting an inductive content analysis process.20 A.W.F. first sorted the sample posts, which were then read and reviewed two times to allow full immersion in the data and a general sense of the main points. After that, A.W.F. manually coded concepts from each sample comment post into folders of similar concepts (nodes). Coding enabled the organization of the data and identification of additional links between or within the concepts. As the coding process continued, the codes with related content were regrouped into more abstract nodes (categories). The subthemes were then yielded by grouping two or more abstract nodes that had similar underlying stories and meanings. Subthemes with generally similar stories were grouped into the overarching themes, which were named to reflect the salient meaning of the categories. This analysis process was iterative and continued until all posts were coded. A.W.F. thoroughly examined the data to ensure that the themes reflected the data. No new codes were developed after analyzing 10 additional comment posts; instead, there was repetition and confirmation of already collected data, indicating attainment of saturation and adequacy of the sample for addressing the research question.31 The yielded themes represented levels of patterned perceptions or meaning within the social media data.32

For the quantitative component, the study employed manual descriptive content analysis. NVivo 11 and Microsoft Excel were used to gather the frequencies of user tones, language, and intended targets of stigma. A.W.F. assigned tones (positive, negative, mixed, neutral) and language types (formal, colloquial, mixed) to the sample posts. To describe stigma, no (0) or yes (1) was assigned to each sample post to determine the presence of stigma. For the posts with stigmatizing comments, A.W.F. categorized the intended targets of stigma, such as the practicing cultures. The frequencies and percentages were compiled in an Excel document and transformed into column graphs and pie charts. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research was used to guide the reporting of the study results (Online Resource 1).

The first author bracketed to neutralize pre-existing conceptions and feelings about FGC that may influence data analysis, interpretation, and selection of data for reporting. The first author took his views into account, identified his expectations of findings, and then consciously put those expectations aside.33 The second author, a University of Ottawa faculty member with expert experience on social media content analysis, reviewed research procedures and offered expert advice.34 This increased the dependability of the research process and the credibility of the findings.

Ethics

The data from YouTube comment sections are public information, making individual informed consent and voluntary participation impractical for this study. For ethical considerations, the study used the data in line with YouTube’s terms and conditions.35 The confidentiality and anonymity of the users were maintained by not displaying user profile names used on YouTube. This is crucial for minimizing participant identification and potential harm to users in the reporting of the study results. As section 12 of YouTube’s policy (“Ability to Accept Terms of Service”) assumes that those under the age of 18 have parental consent before using YouTube services, comment posts from any user deemed to be under the age of 18 (if age was indicated) were overlooked.35

Qualitative results

The content analysis identified four overarching themes from user perceptions of FGC on YouTube: comparing FGC with male genital cutting (MGC), perceived classification of the practice, perceived reason for FGC, and solutions for dealing with the practice.

Comparing FGC with MGC

Equating FGC with MGC

Some users expressed their frustration at the perceived overwhelming attention given to FGC over MGC. As exemplified by the comment below, there was a recurring argument that similar to FGC, MGC was a harmful custom that cut parts of one’s genitals. “They are the same, both cut children genitals. Yet nobody cares about boys.” The users also argued that MGC has no health benefits and instead leads to health issues, causing them to question why MGC was not being condemned and denigrated like FGC.

Differentiating FGC from MGC

Conversely, some users claimed that MGC is incomparable to FGC because it has health benefits, with HIV prevention being a cited example. They further iterated that MGC does not harm boys as it only cuts the foreskin, which some users argued to be less harmful than clitorectomy. A poster contended that “Female Genital Mutilation is beyong more dangerous then circumcision, it is cutting off literally like the tip of a penis at 8 years old.” Users also reasoned that unlike MGC, FGC can kill or disable women during reproduction and can reduce sexual pleasure. Users further reflected that equating MGC with FGC creates false equivalencies that negate the significance of preventing or abolishing FGC.

Classifying the practice

Harmful

The most common subtheme in the comments was the portrayal of FGC as a harmful and barbaric procedure, as exemplified by a popular post that stated, “It’s great that they are raising awareness to this barbaric practice no one should undergo this terrible procedure.” Related arguments of the pain girls and women experience while undergoing FGC reinforced the popular post. In consort, a few users listed the medical consequences that girls and women experience, including maternal bleeding and infections. Others further argued of the long-term psychological trauma that results from FGC.

Child abuse and child rights

Some users argued that genital cutting is child abuse due to the physically violent component of the cutting procedure. One of these users stated, “this is absolutely disturbing and is torture. These poor young children are being tortured. This is something that must be stopped.” Most claims that FGC inflicts harm on children were accompanied with mentions of the painful excision of the clitoris, cutting of the labia, or sewing of the vagina. Others also alluded to the emotional trauma a child undergoing FGC might experience and the adverse effect it can have on their emotional development. Most users classifying FGC as child abuse further contended that FGC was a direct violation of children’s rights because it is performed on children without their consent.

Normal cultural tradition

In contrast to the previous classifications, a few users argued that FGC is a standard cultural tradition that is customary to practicing cultures. These users claimed that judgments of FGC as an abnormal practice were due to Western ethnocentrism. One user had this to say: “Why do western busy bodies feel the overwhelming need to tell other people what to do and how to act?” Other users further stipulated that the condemnation surrounding FGC was based on Western values, standards, and beliefs of cultural superiority from Westerners over FGC-practicing cultures. They also indicated that the tradition was negatively portrayed due to a xenophobic demonization of African traditions in the Western media and from Western people. A couple of users also stated that the mischaracterization and disproportionate focus on infibulation over clitorectomy and excision was misleading, arguing that infibulation was the least commonly practiced type of FGC.

Blame for FGC

Religion

YouTube comments also displayed users’ perceived reasons or blame for the presence of FGC, largely from users who believed it to be an adverse practice. Many users claimed that Abrahamic religions were the main culprit for the practice. As one poster conveyed, “and thats the beauty of islam . . . cut your clitoris off because the prophet said so,” users predominantly blamed Islam, referring to hadith texts and Islamic clerics that support FGC. One user blamed Christianity, referring to Coptic and Orthodox Christians that practice FGC in Egypt and Ethiopia, respectively.

Culture

Others within this theme said that primitive cultural traditions were the cause of FGC and its consequences. Some users were adamant to distinguish religion from culture; one variant of such posts claimed that, “it’s got nothing to do with religion, it’s their cultures at fault!!” Among those who identified certain cultures, users mainly blamed African cultural traditions and Africans, with references to the prevalence of the practice throughout the continent. Others faulted African cultures with arguments that FGC was a cultural rite of passage for a girl to be considered a woman in FGC-practicing communities in Africa.

Parents

Some users also blamed parents for forcing FGC or allowing FGC to be carried out on their daughters. One user stated, “Any parent that makes that choice for their child should be very ashamed.” Fathers, in particular, were said to enforce the practice because they want to control their daughter’s sexuality. A few users faulted mothers for imposing or enabling the practice on their daughters, which according to some, was because they had the procedure done on them in their youth.

Gender inequality

In parallel with some of the reflections on fathers or other males enforcing FGC within a community, some posters also attested that the practice originates from deep-lying gender inequalities in patriarchal societies. One such post stated that men “all over the earth since the dawn of mankind have tried to control women’s sexuality . . . it’s 2015 and we are still discussing wage equality, a rape culture, victim blaming, etc.” Other posts explained that the patriarchal societies in African communities are where men control the daily lives of women, including their sexuality and reproductive choices. In addition to subjugating women’s sexuality, users depicted men as oppressive and self-serving for prioritizing their interests on women’s pre-marital virginity, marital fidelity, and male sexual pleasure.

Solutions for dealing with the practice

Education

Users mostly referred to education as a solution for mitigating or preventing FGC. This was exemplified in one user’s suggestion to “heavily educate people and advertise against that evil practice.” A reappearing topic was the perceived ability of education to change the traditional gender roles that perpetuate gender discrimination and empower girls. Providing girls with education was said to be a pivotal way to prevent FGC either because educated girls were less likely to be financially dependent or because they would not allow their daughters to be cut in the future. Other users proposed religious education strategies to distance FGC from Quranic or Biblical associations, such as through the use of renowned religious leaders or community leaders. In opposition to cultural relativism, one proponent of education directly argued that culture is not an excuse for violence against children. The user proposed that with cultures always changing, culturally sensitive education would be the best option for stopping FGC.

Cultural relativism

Some users argued for employing cultural relativism as a solution, ultimately to garner acceptance for other cultural practices. This was exemplified by a user that said, “we may not agree but this is THEIR culture . . . Outsiders shouldn’t go in telling other people how to run their lives . . . some things that the tribes do should be left alone.” Users who reiterated such comments proposed that since FGC is an essential rite of passage and tradition for some cultures, the practice and the practicing cultures should be tolerated instead of being criticized and denigrated. This proposal was reinforced by analogies involving Western cultural acts that people from non-Western cultures may chastise and judge to be abnormal, such as piercings on the clitoris. Some users concluded that there is no right or wrong cultural practices as perceptions of right and wrong vary between cultures.

Combat

Four posters articulated how the only way to prevent or abolish FGC was to attack practicing cultures by bombing the practicing regions, extinguishing Africa, or using international troops to overthrow men and relieve women in FGC-practicing communities. One of these posters explained their alternative to anti-FGC campaigns: “all these campaigns are FUCKING USELESS! want to really stop these fuckers? just bomb that whole SHITHOLE off earth and the mutilations go with it!!”

Praise

A few posters expressed support for the cut girls or women through praises about their strength. One poster wrote, “god bless this women . . . I admire her courage I hope we can all make a difference and change the world like her inshallah.” Some requests about or toward God saving girls and women from undergoing FGC accompanied posts that praised cut girls.

Adopt

One comment poster was adamant about FGC being unethical and expressed their wish to adopt cut girls from practicing regions: “its torture and its soo so so immoral, I wish I could save and bring these abused girls.”

Quantitative results

In the quantitative component, A.W.F. categorized and visualized user posts based on the attitude toward a displayed topic (tone), the way of communicating (formal vs colloquial language), and those that were stigmatized. From the 150 sample posts, 140 (93.3%) were relevant to the topic of FGC. Irrelevant posts, of which there were 10 (6.7%), had no relation to FGC, but often some part of the video, such as the desirability of the women. The majority of the posts were expressing thoughts based on assessments of the video content, including assigning blame for the practice when deemed barbaric (65.3%). Giving advice was the second most prevalent category, with posters proposing education or respect for other cultures (15.3%). Users provided emotional support and praise for those whom they deemed to be victims and survivors of FGC (6.7%). Those who had the procedure done on them reminisced and portrayed their experience and their related thoughts, most of which condemned FGC (6%).

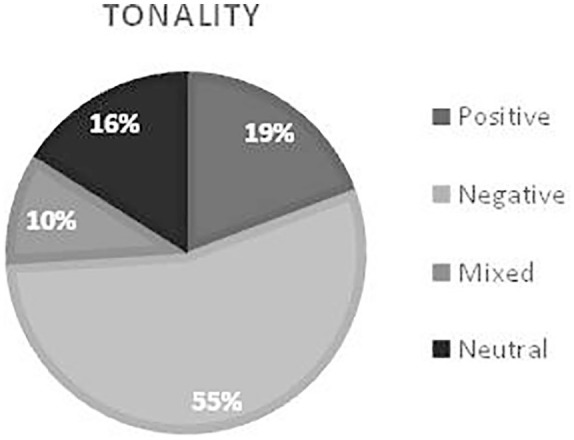

Tone

The authors categorized user posts as positive, negative, mixed, or neutral with regard to their tone (Figure 2). A negative tone, which came from negatively expressed attitudes, was most predominant. Posts that were condemning a specific group were the common source of negative tones, as exemplified by a post exclaiming “disgusting practice . . . why the fuck are we bringing these people here?” Positively expressed attitudes were mainly portrayed in posts that proposed solutions for dealing with the practice, with one participant praising an American woman who underwent FGC in video 5 (Table 1): “thank you for being so strong and brave. Your courage is astounding. God bless you.” Mixed posts contained varying degrees of both negative and positive tones, and were mainly found amid posts that compared MGC with FGC. Neutral posts contained no positive or negative tone, but rather a factual or informative tone. Posts that proposed solutions for dealing with FGC mainly reflected neutral-toned posts.

Figure 2.

Tonality of comments posts.

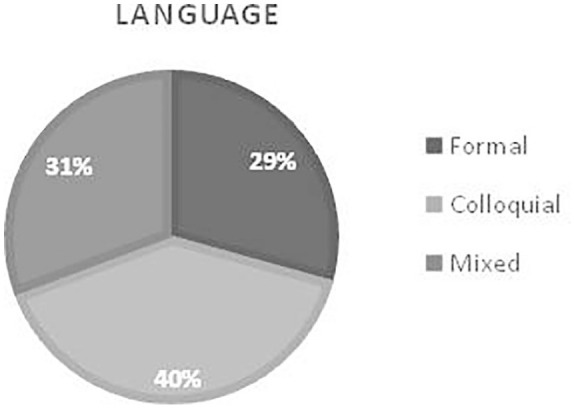

Language

User posts were also categorized as formal, colloquial, or mixed based on the used words and expressions (Figure 3). A post that said “All children, regardless of gender, culture or parental religion, have a fundamental right to keep all their healthy, functional genitalia” exemplified formal language. Formal language included impersonal, non-colloquial, and professional sentences. Formal language was much portrayed in posts that proposed solutions, particularly posts that argued for education and cultural relativism. Informal or colloquial language was highly depicted in posts that debated MGC versus FGC and assigned blame for the FGC practice. Colloquial language included texts with abbreviations, first-person pronouns, emojis, misspellings, contractions, and homonymic rebuses. An example of colloquial language was seen in a post that posed a rhetorical question: “What the heck cut the critoris? What a bunch of weirdos!!!” A mix of colloquial and formal language was typically found in posts that labeled FGC as harmful or barbaric, as well as posts about gender inequality.

Figure 3.

Type of language used in comment posts.

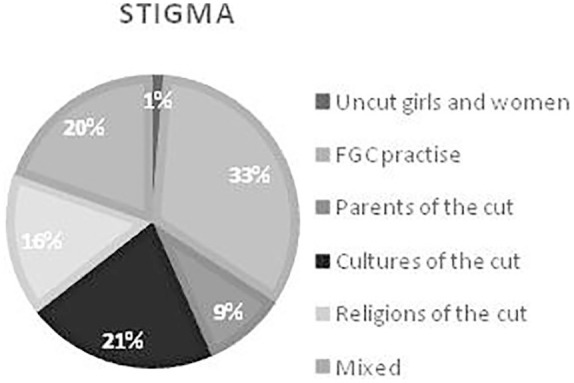

Stigma

Seventy-six of the posts denounced the FGC practices, religions, cultures, uncut females, and parents of those who were cut (Figure 4). A user described uncut women as impure and unclean for having evaded the procedure. The FGC practice was the most stigmatized target, with a common characterization of the practice as primitive and barbaric. Parents of cut girls and women were labeled as inferior and unfit parents for enforcing or allowing their girls to be cut. Islam and African cultures accounted for the vast majority of the stigma toward religion and culture, with many users condemning Islam, African cultures, and their associated members for enforcing or enabling the practice of FGC. Fifteen of the individual posts stigmatized at least two targets, which usually consisted of the FGC practice along with Islam and/or Africans.

Figure 4.

Intended targets of stigmatizing comment posts.

Discussion

This study explored and described the portrayal of FGC among a selected sample of YouTube users using a mixed-method approach. The qualitative content analysis identified comparisons of FGC with MGC, classification of FGC, blame for FGC, and solutions for dealing with FGC as the overarching themes. The quantitative content analysis identified a range of tones and language types, as well as targets of stigma in the users’ comment posts.

Many debate the similarities and dissimilarities between FGC and MGC in the media and in the literature. Users who explicitly compared FGC with MGC perceived that MGC was a physically harmful custom that removed parts of the genitalia—like FGC. This is consistent with The Atlantic magazine readers’ comments about the merits and ethics of male circumcision in response to an interview on the negative coverage and misconceptions of FGC in the West.36 Some academic scholars similarly contend that MGC is a risky procedure. They support this stance by arguing about double standards and misleading bioethical and moral distinctions conveyed in anti-FGC narratives.37–40 Conversely, YouTube users who perceived that MGC was in no way comparable to FGC reasoned that contrary to FGC, MGC had low to no health risks, and had potential health benefits. For these users, the mere mention of MGC in a likening tone with FGC was akin to support for FGC and an erroneous stance forged by false equivalencies. Many online media forums, anti-FGC campaigns and advocacy groups, academic literature, and gray literature sources present confirmatory arguments that push for a separate bioethical discourse between FGC and MCG.41–43

Similar to comparisons drawn in this study, some scholars draw cross-cultural similarities between FGC and other body-altering practices, such as female genital piercings.44,45 While other body-altering practices in the West make their way into the “cosmetic” classification, the scholars contend that anatomically identical procedures conducted on women in FGC-practicing areas are unfairly branded as “mutilation.” Semantic disputes about the correct terminology for the practice continue to be a substantial cause of controversy, especially among advocates of cultural relativism and sensitivity, and stark opponents of FGC. The term “cutting” is often used in the academic literature because it is neutral, medically accurate, and culturally sensitive.43 However, campaigns against the practice and global organizations use the term “mutilation” to bring attention to the severity of the practice. Although practicing communities use the term “circumcision,” global organizations such as the WHO and United Nations attest that the term “circumcision” normalizes the practice, undermines the sexual subjugation of women, and invites false equivalencies with male “circumcision.”43 Those who refer to both FGC and MGC as “circumcision” or “surgery” argue that the term “mutilation” is derogatory and that it can lead to the isolation and estrangement of practicing populations. In this study, there was no clear pattern regarding the terminological use of cutting, mutilation, and circumcision. YouTube posters used these terms interchangeably, which was especially surprising in comments under Tucker’s contentious video, “Don’t Call it Mutilation,” which included this terminological dispute in the video title and in the video.

By extension, classifications of the practice, whether in social media or the literature, tend to feature similar controversies as the semantic disagreements. The comment sections under each video commonly featured conflicting classifications of FGC as a harmful and barbaric practice, and classifications of FGC as a normal practice that has been demonized by Western-centric bias. Reinforcing the former classification, renowned global organizations and countless academic scholars decisively identify the practice as a harmful practice with significant health risks and no health benefits.46–48 There were also classifications of the practice as a form of child abuse because of the pain associated with FGC procedures. These users further underscored infringements on children’s rights, articulating that girls either do not consent to FGC or that parents, cultures, or religion force their consent. The WHO and scholars persistently describe FGC as a violation and discrimination of the sexual and reproductive rights of girls and women.1,49 The practice also contains deeply entrenched gender-based inequalities that enforce the practice on children, adolescents, and women without their consent. This is consistent with some users’ perceptions that patriarchy and gender power dynamics in practicing regions were geared to favor men, and do so in part by controlling women’s sexuality and sexual decisions.

In contrast, users who perceived that FGC was as normal as any other cultural procedure, including those done in the West, argued that Western ethnocentrism and racism were responsible for the distorted and prejudiced characterization of FGC and its practitioners as barbaric and abnormal. This is reiterated by Njambi,50 who argues that portrayals of FGC as barbaric, gender-based oppression and a human rights issue reflect Western imperialism and Western images of normality and superiority over FGC-practicing communities. Nnaemeka51 contends that most negative portrayals of FGC distort the sociocultural and socioeconomic factors that hinder and enable the practice. Some anti-FGC critics often argue that negative portrayals of FGC explicitly focus on the most extreme cases and the most severe consequences that result from infibulation, despite the fact that it is less common than clitoridectomy and excision.51,52 According to the Public Policy Advisory Network on Female Genital Surgeries in Africa (PPANFGSA),52 media coverage in particular relies largely on anti-FGC activist sources and thereby provides inaccurate, overgeneralized, and disproportionate representations of the practice. The implication here is that negative portrayals of FGC do not provide a balanced perspective on the multiple factors that influence the practice. Composed of research scholars, physicians, and policy experts, the controversial PPANFGSA claims to strive for greater accuracy in cultural representation of FGC and impartiality in media coverage and policy debates. Nevertheless, many of the stances taken in their article, such as one that FGC is controlled, influenced, and performed by women rather than patriarchs, distorts supporting evidence and largely conflicts with the pattern of findings in the literature on the health, social, and mental consequences of FGC.

In all eight comment sections, proposed solutions to preventing or ending FGC mainly called for educational interventions. Education as an intervention, through a range of delivery platforms, is a common suggestion in the literature for altering deeply entrenched practices and beliefs related to FGC.53–55 Recommended platforms of delivery include community and outreach services, conventional health services, school-based seminars, and digital media messages. The proposed targets of various forms of educational interventions are girls, women, men, traditional cutters, religious leaders, and other opinion leaders.56,57 Similar to study findings, a report by UNICEF56 and systematic review by Waigwa et al.57 reported the needs for health education and religious education interventions targeting a range of community members. These references also identified the need for education to drive social and cultural change, as suggested in some YouTube comments. Other users conversely proposed solutions aiming to increase acceptance of practicing cultures’ procedures and to dissuade discourse that classifies FGC through Western standards of normal and abnormal customs and beliefs. For cultural relativists, the condemnation of FGC and the portrayal of practicing communities as barbaric and backwards are outcomes of Eurocentrism and poor awareness of one’s cultural frameworks and biases.58,59 They also perceive that opposition to FGC is a way of enforcing Western concepts and values on the non-Western world.

Across the comment sections, the tonality was predominantly negative due to the frequent depiction of FGC as a harmful, child-abusing, or gender discriminating practice. Other contributors were posts incriminating Islam and African cultures, as well as dissent from users who protested for MGC to get equivalent attention and for anti-FGC campaigns to be toned down. Not surprisingly, user posts were mainly colloquial, which is an accurate representation based on the literature on YouTube comments orthography.60 The dominant use of colloquial language, such as in posts incriminating Muslims and Africans, created a conversational tone often seen in cyber language; however, it also implied user hurriedness while writing and a lack of editing. The formal language, which was predominantly used in posts that proposed educational interventions or cultural relativism, had a more academic tone and suggested advanced editing and revision while writing the posts.61 Consistent with research findings, user posts mainly stigmatized African cultures, Islam, and the FGC practice with characterizations related to primitivism, barbarism, and savagery.62,63 Given the ability to remain anonymous, social media commonly features stigmatization, usually through the denigration of targeted individuals, groups, and their beliefs. Regardless of whether one believes that these denigrations are warranted or not, the possibility that stigmatizing discourse can alienate targeted groups implies that the global community needs to better understand how to form a safer and healthier world for girls in or from FGC-practicing communities.

To identify and compare recent trends to study findings, the comment sections under five FGC relevant YouTube videos published between 2019 and 2020 (1st, 5th, 10th, 15th, and 20th most popular videos from our search strategy in Figure 1) were perused. The posts reiterated majority of the depictions identified in this study, namely, classifications of the practice as savage and abusive, comparisons between MGC and FGC, and blame of cultures and Muslims. However, one stark difference in the recent trends of comment posts was the significantly larger proportion of politically charged posts. The recent comment posts displayed the following politically charged depictions: blame liberals and diversity for persistence of FGC; blame conservative cultures for persistence of FGC; “feminazis” hijacked campaigns against FGC and actively downplay MGC; White male patriarchy and Western cultures are not the problem. Other new posts, which were not political, depicted the following perceptions: FGC practitioners should be imprisoned; user unawareness of the presence of FGC in a specific country; FGC has benefits and is safe, but cutters need better training; there are more important issues than FGC.

The mixed-method nature of this study enabled the detailed analysis of patterns within and across the data. Another methodological strength of this study was the use of naturally expressed opinions because it enables the analysis of data that were not collected or otherwise influenced by this study’s authors. There are also limitations in this study. First, there may be selection bias resulting from reliance on data from users who are more Internet-active and particularly more active on YouTube comment sections. There may also be selection bias by including users who happen to be more incited by topics such as FGC. Second, considering the large amount of YouTube comments and a few of the differences found in the recent trend of comments, the study findings cannot be said to be entirely generalizable or transferable to all YouTube users who comment about FGC-related topics. Also, given that the findings are only based on YouTube data, transferability and generalization to social media users with opinions on FGC is further constrained.

Third, the analysis of YouTube posts does not account for paralinguistic communication, which likely constrained the first author’s interpretation of the messages. In addition, only a few users employed tools of emotional expressions, such as emoticons, thereby providing minimal insight to the analysis. Fourth, YouTube users can delete their own comments, and report others’ comments for removal. Consequentially, the available comments may not be representative of the depth of various perceptions about FGC on the platform. Another limitation of this study is the implication from the study findings that opposition to FGC is merely a Western stance. In reality, strong opposition to FGC can be found even in FGC-practicing regions.

Conclusion

This study analyzed YouTube comment posts that reveal the portrayal of FGC, thereby adding to an overlooked gap in the academic literature on the portrayal of FGC on social media. The analysis suggested that the portrayal of FGC on social media cannot be simply characterized into those who oppose the practice and those who defend it. The controversial and complex topic rather provided valuable insights into the wide array of perceptions, beliefs, and opinions of users who opposed FGC, defended FGC, both opposed and defended the practice, or took a neutral stance. The first major disparity featured conflicting comparisons between FGC and MGC. YouTube users also conflictingly classified FGC either as a harmful and unethical practice or as a normal tradition demonized by Western bias. Furthermore, religion, African cultures, and gender inequality were identified as key facilitators of FGC. Finally, YouTube users conflictingly suggested a need for education to combat FGC or cultural relativism to cope with FGC.

The study findings have several implications and lead to recommendations for current interventional needs and future research directions. The findings indicate the need for education as a means to spread knowledge about the dangers of FGC and to dispel misinformation and misconceptions about the practice. For example, organizations attempting to distinguish MGC from FGC or traditional practices from religious beliefs can use social media data to inform the development of educational and promotional campaigns. On the contrary, program evaluators attempting to determine the effect of their program on knowledge and awareness or on the presence of stigma against a targeted group on social media, such as Africans, can refer to this study’s findings. This can also help to gage and evaluate the impact of programs that aim to reduce misinformation and misconceptions, including those that contribute to the stigmatization of certain regions, ethnicities, races, and religions. Social media platforms, including YouTube, have shown that they can effectively facilitate knowledge sharing and sway perceptions and attitudes about sensitive social and political topics.54,64 Therefore, considering the networking abilities, reach, and spread of social media, our findings reinforce literature evidence on the potential significance of social media platforms as conduits to encourage action against FGC, shift attitudinal paradigms, drive sociocultural change, and display positive change stories.54 In consort, future interventions can continue to use the ever growing online technological advances to share evidence-based information, raise awareness, and highlight critical and persisting FGC-related issues to a wide audience.

Further exploration of FGC-related discussions on social media platforms can provide informative insights for campaigns, advocacy efforts, and policy transformation. Social media forums, including YouTube comment sections, amass new comments and unique perceptions on a daily basis, suggesting the need for larger, more systematic studies. For example, systematic comparisons of posts from more YouTube comment sections or across various social media platforms, in various languages, can help to render a broader ethnographic perspective. Future research should also consider triangulating findings by using multiple qualitative and quantitative research methods and tools, including correlation and relationship analyses, regression analysis, active ethnographic participation, and thematic analysis. In addition, given that social media users’ perceptions can change over time, future research should attempt to conduct longitudinal research into user perceptions.

This manuscript attempts to present a balanced and neutral analysis of FGC. Nevertheless, the authors would like to highlight that the literature provides overwhelming evidence supporting the contention that FGC has adverse effects on girls’ and women’s health, security, and bodily integrity. Furthermore, we would like to iterate that there is vast evidence to show that equivalencies between MGC and FGC, drawn in public discourse, especially when the latter pertains to excision and infibulation, are really false equivalencies. These types of public discourses on the topic of FGC may in fact be more damaging to anti-FGC campaigns in the long run. Furthermore, we strongly believe that ethnically or religiously charged castigations of practicing communities, by anti-FGC advocates on social media, will be detrimental to driving the necessary sociocultural changes. In fact, it could lead to further alienation of the castigated, who may construe any other anti-FGC message as a bigoted statement.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anne TM Konkle  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2327-1172

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2327-1172

References

- 1. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation. Report, 2016, https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/management-health-complications-fgm/en/ [PubMed]

- 2. The United Nations Children’s Fund. Female genital mutilation/cutting: a global concern, https://data.unicef.org/resources/female-genital-mutilationcutting-global-concern/ (2016, accessed 20 May 2020).

- 3. Berg RC, Underland V. The obstetric consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013; 2013: 496564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alsibiani SA, Rouzi AA. Sexual function in women with female genital mutilation. Fertil Steril 2010; 93(3): 722–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation: Key facts, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ (2018, accessed 15 June 2019).

- 6. Varol N, Fraser IS, Ng CH, et al. Female genital mutilation/cutting—towards abandonment of a harmful cultural practice. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 54(5): 400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yagoub A, Satti A, Elhakim E. Female genital mutilation: a continuing battle for eradication. Women’s Health 2007; 3(4): 385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abdulcadir J, Margairaz C, Boulvain M, et al. Care of women with female genital mutilation/cutting. Swiss Med Wkly 2011; 140: w13137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elechi O. Doing justice without the state: The Afikpo (Ehugbo) Nigeria Model. 1st ed: Exeter: Routledge, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kennedy A. Mutilation and beautification. Aust Fem Stud 2009; 24(60): 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maynard D, Roberts I, Greenwood M, et al. A framework for real-time semantic social media analysis. J Web Semant 2017; 44: 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carpenter LM, Kettrey HH. (Im)perishable pleasure, (in)destructible desire: sexual themes in US and English news coverage of male circumcision and female genital cutting. J Sex Res 2015; 52(8): 841–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sobel M. Female genital cutting in the news media: a content analysis. Int Commun Gaz 2015; 77(4): 384–405. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wade L. Defining gendered oppression in U.S. Newspapers: the strategic value of “female genital mutilation.” Gend Soc 2009; 23(3): 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wade L. Learning from “female genital mutilation”: lessons from 30 years of academic discourse. Ethnicities 2011; 12: 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16. YouTube. YouTube for press, https://www.youtube.com/about/press/ (2019, accessed 19 May 2020).

- 17. Alexa. Youtube.com Competitive analysis, marketing mix and traffic, https://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/youtube.com (2019, accessed 17 May 2020).

- 18. Madden A, Ruthven I, McMenemy D. A classification scheme for content analyses of YouTube video comments. J Doc 2013; 69(5): 693–714. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Creswell J, Clark VC. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62(1): 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lai LSL, To W. “Content analysis of social media: a grounded theory approach.” J Electron Commer Res 2015; 16(2): 138–152. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Terlumun IT, Appollm YI. Determining the effectiveness of Youtube videos in teaching and learning with Mozdeh algorithm. Int J Educ Eval 2018; 4(4): 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ali K, Hamilton M, Thevathayan C, et al. Social information services: a service oriented analysis of social media. In: International conference on web services, Seattle, WA, 25 June–30 June 2018, pp. 263–279. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Anand A, Irshad MS, Aggrawal N, et al. View-count based modeling for YouTube videos and weighted criteria–based ranking. In: Ram M, Davim JP. (eds) Advanced Mathematical Techniques in Engineering Sciences. 1st ed Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, 2018, pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rieder B, Matamoros- Fernández A, Coromina Ò. From ranking algorithms to “ranking cultures”: investigating the modulation of visibility in YouTube search results. Convergence 2018; 24: 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Covington P, Adams J, Sargin E. Deep neural networks for YouTube recommendations. In: Proceedings of the 10th ACM conference on recommender systems, Boston, MA, 15–19 September 2016, pp. 191–198. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Madrigal AC. How YouTube’s algorithm really works, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/11/how-youtubes-algorithm-really-works/575212/ (2018, accessed 16 May 2020).

- 28. Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL. A call for qualitative power analyses. Qual Quant 2007; 41: 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gupta S, Khan Z, Shabbir J. Modified systematic sampling with multiple random starts. Revstat Stat J 2018; 16(2): 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Madow WG, Madow LH. On the theory of systematic sampling, I. Ann Math Stat 1944; 15: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Speziale HS, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malterud K. Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40(8): 795–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Billups F. The quest for rigor in qualitative studies: strategies for institutional researchers. NERA Res 2014; 52(1): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 35. YouTube. Terms of Service—YouTube, https://www.YouTube.com/static?gl=CA&template=terms (2018, accessed 18 July 2019)

- 36. Bodenner C. How similar is FGM to male circumcision? Your thoughts. The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/05/male-circumcision-vs-female-circumcision/392732/ (2015, accessed 15 June 2019).

- 37. Dalton JD. Male circumcision—see the harm to get a balanced picture. J Mens Health Gend 2007; 4(3): 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Earp BD. Do the benefits of male circumcision outweigh the risks? A critique of the proposed CDC guidelines. Front Pediatr 2015; 3: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Evans M. Circumcision in boys and girls: why the double standard? BMJ 2011; 342: d978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. MacNeily AE. Routine circumcision: the opposing view. Can Urol Assoc J 2007; 1(4): 395–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Andro A, Lesclingand M, Grieve M, et al. Female genital mutilation. Overview and current knowledge. Population 2016; 71(2): 217–296. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gruenbaum E. The female circumcision controversy: an anthropological perspective. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perron L, Senikas V, Burnett M, et al. Female genital cutting. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013; 35(11): 1028–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bell K. Genital cutting and Western discourses on sexuality. Med Anthropol Q 2005; 19(2): 125–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shahvisi A, Earp BD. The law and ethics of female genital cutting. In: Creighton S, Liao LM. (eds) Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery: Solution to What Problem? 1st ed Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019, pp. 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bjälkander O, Bangura L, Leigh B, et al. Health complications of female genital mutilation in Sierra Leone. Int J Womens Health 2012; 4: 321–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. World Health Organization. Health risks of female genital mutilation (FGM), https://www.who.int/sexual-and-reproductive-health/health-risks-of-female-genital-mutilation (n.d., accessed 15 January 2018).

- 48. Kaplan A, Hechavarría S, Martín M, et al. Health consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting in the Gambia, evidence into action. Reprod Health 2011; 8: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dustin DH, Davies LA. Female genital cutting and children’s rights: implications for social work practice. Child Care Pract 2007; 13: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Njambi WN. Dualisms and female bodies in representations of African female circumcision: a feminist critique. Fem Theory 2016; 5(3) 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nnaemeka O. Female circumcision and the politics of knowledge: African women in imperialist discourses. 1st ed Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Public Policy Advisory Network on Female Genital Surgeries in Africa. Seven things to know about female genital surgeries in Africa. Hastings Cent Rep 2012; 42(6): 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Abathun AD, Sundby J, Gele AA. Pupil’s perspectives on female genital cutting abandonment in Harari and Somali regions of Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health 2018; 18: 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Julios C. Female genital mutilation and social media. 1st ed: London: Routledge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eisele J. Female genital circumcision social indicators that influence attitudes on abandonment of FGC in Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56. The United Nations Children’s Fund. Changing a harmful social convention: female genital mutilation/cutting. Report, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, January 2008, https://data.unicef.org/resources/changing-a-harmful-social-convention-female-genital-mutilationcutting-innocenti-digest/#:~:text=Changing%20a%20Harmful%20Social%20Convention%3A%20Female%20genital%20mutilation%2Fcutting,-January%202008&text=This%20Innocenti%20Digest%20examines%20the,elements%20necessary%20for%20its%20abandonment.

- 57. Waigwa S, Doos L, Bradbury-Jones C, et al. Effectiveness of health education as an intervention designed to prevent female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): a systematic review. Reprod Health 2018; 15: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Milde FR. Theories on female genital mutilation. Report, Uppsala Universitet, October 2012, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2250346#:~:text=The%20causes%20of%20FGM%20include,(WHO%202010%3A241).&text=Complicating%20factor%20in%20the%20moral,practiced%20and%20advocated%20by%20women.

- 59. Sarkis MM. Anthropology and female genital cutting (FGC). In: Denniston GC, Hodges FM, Milos MF. (eds) Flesh and blood: perspectives on the problem of circumcision in contemporary society. 1st ed New York: Springer, 2004, pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gentles-Peart K, Hall ML. Re-Constructing place and space: media, culture, discourse and the constitution of Caribbean diasporas. 1st ed Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61. University of Southern Carolina Library. Research guides: organizing your social sciences research paper: academic writing style, https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/academicwriting (2018, accessed 10 June 2019).

- 62. Betton V, Borschmann R, Docherty M, et al. The role of social media in reducing stigma and discrimination. Br J Psychiatry 2015; 206(6): 443–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Robinson P, Turk D, Jilka S, et al. Measuring attitudes towards mental health using social media: investigating stigma and trivialisation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2019; 54(1): 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ribeiro MH, Ottoni R, West R, et al. Auditing radicalization pathways on Youtube. In: Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, Barcelona, 27–30 January 2020, pp. 131–141. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]