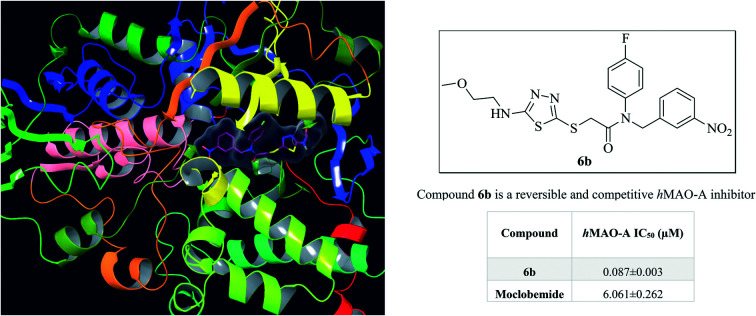

Compound 6b is a reversible and competitive hMAO-A inhibitor.

Compound 6b is a reversible and competitive hMAO-A inhibitor.

Abstract

Monoamine oxidases (MAOs) are important drug targets for the management of neurological disorders. Herein, a series of new 1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives bearing various alkyl/arylamine moieties as MAO inhibitors were designed and synthesized. All of the compounds were more selective against hMAO-A than hMAO-B. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of most of the compounds were lower than that of the common drug moclobemide (IC50 = 4.664 μM) and compound 6b was proven to be the most active compound (IC50 = 0.060 μM). Moreover, it was seen that compound 6b showed a similar inhibition profile to that of clorgyline (IC50 = 0.048 μM). The inhibition profile was found to be reversible and competitive for compound 6b with MAO-A selectivity. Molecular modelling studies aided in the understanding of the interaction modes between compound 6b and MAO-A. Furthermore, this compound was predicted to have a good pharmacokinetic profile and high BBB penetration. Therefore, such compounds are of interest towards developing new MAO inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is a flavoenzyme that exists in all mammalian tissues, placed at the outer membrane of the mitochondria as an integral protein.1–3 The MAO enzyme has 2 isoforms: MAO-A and MAO-B. Their amino acid sequences have 70% similarity.4,5 However, they are encoded from separate genes and they have been identified by their substrate selectivity, inhibitor sensitivity, and 3-dimensional structures.6–8 Catalysis of the biological amine oxidative deamination reaction is carried out by MAO isozymes.9 The inhibition of noradrenaline, adrenaline, and serotonin is carried out by MAO-A, while the inhibition of phenylethylamine and benzylamine is carried out by MAO-B. Both dopamine and tyramine are oxidized by the MAO-A and MAO-B isoenzymes.10–12 Abnormal activation or a decrease in levels of the MAO enzymes in humans has been associated with depression, autism, drug addiction, and neurodegenerative diseases.13,14

MAO isoenzymes have broad pharmacological importance due to their roles in the metabolism of certain neurotransmitters. In major depression-related diseases, a deficit of monoamines is observed, basically norepinephrine and serotonin, at critical synapses in the central nervous system. In Parkinson's disease, the concentration of dopamine is decreased.15 Selective MAO-A inhibitors are used clinically as antidepressants and anxiolytics. MAO-B inhibitors are used to reduce the progression of Parkinson's disease, and manage symptoms related to Alzheimer's disease.16–18 MAO-A and MAO-B inhibitors provide the treatment of these diseases by inhibiting MAO isoenzymes and thus regulating the reduced levels of the relevant neurotransmitters. Considering the monoamine deamination function of MAO, results have shown that MAO inhibitors play a critical role in the therapy of severe neurological and psychological disorders.19,20

Research in the area of medicinal chemistry has resulted in a significant number of derivatives based on a variety of oxygen-, sulphur-, and nitrogen-containing compounds.21–23 One of the main goals of medicinal chemistry is the discovery of novel safer and better-tolerated therapeutic agents. Thiadiazoles are a very important class of heterocyclic compounds, possessing diverse biological activities, such as antimicrobial,24 antitumor,25 antihypertensive,26 antifungal,27 antimycobacterial,28 antitubulin,29 antiviral,30 antioxidant,31 antileishmanial,32 and carbonic anhydrase33 and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory34 activities.

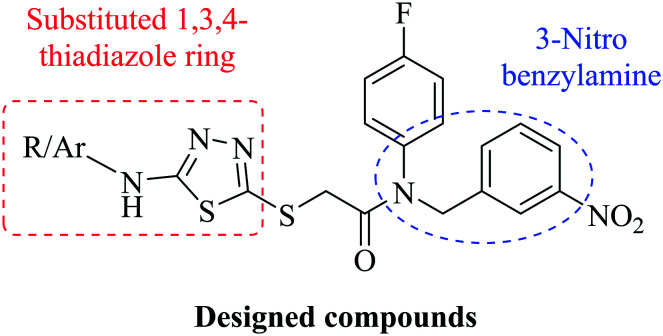

Some studies have indicated that the benzylamine moiety possesses MAO inhibitory activity.35–37 Previously, our research group synthesized new compounds and examined them in terms of their hMAO inhibitory activity, mechanism of enzyme inhibition and physicochemical properties.9,38–45 In one of our studies, compounds containing a benzothiazole ring in addition to the benzylamine moiety were synthesized. Some compounds displayed considerable inhibitory activity against the MAO-A and MAO-B enzymes.46 In this study, new compounds were designed and synthesized using the 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring with a different alkyl/arylamine structure instead of the benzothiazole ring (Fig. 1). Moreover, the physicochemical properties and pharmacokinetic profiles of the obtained compounds were predicted with the help of computational methods. The in vitro fluorometric method was conducted to evaluate their inhibition profiles on the MAO isoenzymes. The mechanism of enzyme inhibition also was determined by enzyme kinetic studies. Furthermore, molecular docking studies were carried out to gain structural insight into the binding modes of the synthesized compounds in the enzyme active site.

Fig. 1. Structure of the designed compounds by combining a substituted 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring (the red rectangle) with an arylamine (the blue circle).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

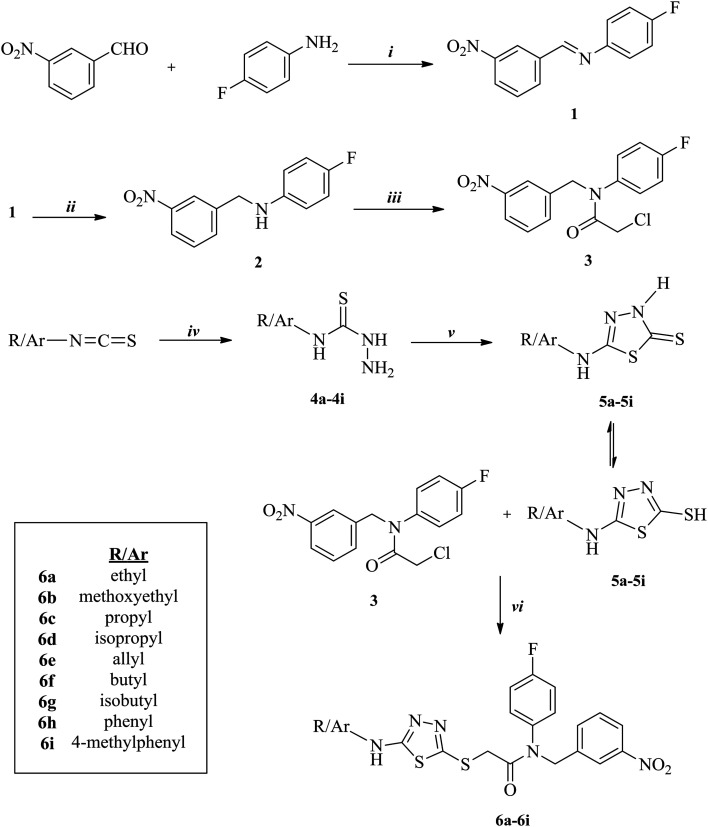

The synthetic route used in this work is outlined in Scheme 1. The condensation of 3-nitrobenzaldehyde and 4-fluoroaniline at reflux yielded compound 1. Subsequently, to synthesize compound 2, the imine bond was reduced in methanol with sodium borohydride in portions. Next, compound 3 was afforded with the reaction of compound 2 and chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine. Substituted isothiocyanate derivatives were reacted with hydrazine hydrate to synthesize compounds 4a–4i. Nine 5-substituted amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2(3H)-thione derivatives (5a–5i) were obtained via the ring closure reaction of compounds 4a–4i with carbon disulfide in the presence of potassium hydroxide. Finally, compounds 5a–5i were treated with compound 3 in acetone in the presence of potassium carbonate to acquire target compounds 6a–6i. Synthesis of the desired compounds were achieved with 62–81% yields. All of the acquired compounds were purified by crystallization. The results of the spectral analysis performed to characterize the structures of the compounds were in accordance with the assigned structures.

Scheme 1. The synthetic pathway of compounds 6a–6i. Reagents and conditions: i: CH3COOH, EtOH, reflux, 8 h; ii: NaBH4, MeOH, room temperature (r.t.), 10 h; iii: ClCH2COCl, TEA/THF, ice-bath, 5 h; iv: NH2NH2·H2O, EtOH, r.t., 4 h; v: (1) CS2/KOH, EtOH, reflux, 10 h; (2) HCl, pH 4–5; vi: K2CO3, acetone, r.t., 8 h.

In the 1H NMR spectra, CH2 protons bound to the carbonyl group and nitrogen were observed at between 3.89–4.02 ppm and 5.00–5.02 ppm, respectively. The signal belonging to the NH proton was determined at between 7.70 and 7.94 ppm, in the spectra of compounds 6a–6g, which had a 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring and an alkyl moiety both bound to nitrogen. The same signal was detected at 10.35 ppm and 10.25 ppm, respectively, in compounds 6h and 6i, which possessed 1,3,4-thiadiazole and phenyl rings both bound to nitrogen. All of the aliphatic and aromatic protons and carbons were assigned at their expected area. In the mass spectra of the compounds, the [M + 1] peaks were in good agreement with their calculated molecular weights (MWs).

2.2. MAO inhibition assay

All of the obtained 1,3,4-thiadiazole derivatives were investigated for their inhibitory activity against the MAO isoforms using a previously described in vitro fluorometric method, which is based on the detection of H2O2 in a horseradish peroxidase-coupled reaction using 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine (Amplex red reagent).

The assay was carried out in 2 steps. The first step was carried out using concentrations of 10–3 and 10–4 M of all of the synthesized compounds and reference inhibitors, namely moclobemide, clorgyline, selegiline and safinamide. Next, the selected compounds that displayed more than 50% inhibitory activity at a concentration of 10–4 M were further tested, along with the reference inhibitors, at concentrations of 10–5 to 10–11 M. The inhibition percentages and half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of the test compounds and reference inhibitors are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inhibition percentage and IC50 values of the synthesized compounds, moclobemide, clorgyline, selegiline and safinamide against the MAO-A and MAO-B enzymes.

| Compounds | MAO-A %inhibition |

MAO-A IC50 (μM) | MAO-B %inhibition |

|||||||||

| 10–3 M | 10–4 M | 10–5 M | 10–6 M | 10–7 M | 10–8 M | 10–9 M | 10–10 M | 10–11 M | 10–3 M | 10–4 M | ||

| 6a | 93.618 ± 1.974 | 89.506 ± 1.618 | 74.142 ± 1.296 | 61.895 ± 1.102 | 42.088 ± 0.955 | 30.268 ± 0.991 | 21.028 ± 0.882 | 14.201 ± 0.596 | 10.305 ± 0.411 | 0.336 ± 0.014 | 41.255 ± 0.985 | 22.352 ± 0.522 |

| 6b | 94.125 ± 2.884 | 91.548 ± 1.695 | 80.603 ± 1.541 | 72.675 ± 1.324 | 61.082 ± 0.979 | 34.748 ± 0.851 | 26.911 ± 0.805 | 20.074 ± 0.766 | 13.464 ± 0.510 | 0.060 ± 0.002 | 38.625 ± 0.856 | 25.741 ± 0.618 |

| 6c | 95.025 ± 1.902 | 91.102 ± 1.891 | 78.344 ± 1.456 | 62.311 ± 0.999 | 45.147 ± 0.933 | 25.133 ± 0.901 | 20.495 ± 0.896 | 12.036 ± 0.512 | 8.497 ± 0.385 | 0.241 ± 0.011 | 42.689 ± 0.966 | 26.788 ± 0.579 |

| 6d | 92.525 ± 2.011 | 89.142 ± 1.618 | 86.102 ± 1.903 | 46.039 ± 1.045 | 43.014 ± 0.919 | 23.882 ± 0.902 | 13.603 ± 0.588 | 10.801 ± 0.496 | 6.872 ± 0.297 | 1.073 ± 0.051 | 35.963 ± 0.715 | 28.455 ± 0.539 |

| 6e | 92.005 ± 1.809 | 86.418 ± 1.036 | 75.227 ± 1.419 | 56.496 ± 1.110 | 43.161 ± 0.982 | 32.693 ± 0.903 | 20.477 ± 0.872 | 13.529 ± 0.570 | 10.248 ± 0.423 | 0.502 ± 0.023 | 38.125 ± 0.795 | 29.221 ± 0.750 |

| 6f | 90.524 ± 2.015 | 82.308 ± 1.902 | 76.015 ± 1.408 | 47.321 ± 0.983 | 33.582 ± 0.991 | 29.963 ± 0.834 | 19.741 ± 0.716 | 11.088 ± 0.402 | 6.943 ± 0.285 | 1.175 ± 0.050 | 40.567 ± 0.825 | 34.322 ± 0.850 |

| 6g | 93.491 ± 1.988 | 84.276 ± 1.632 | 72.633 ± 1.408 | 43.189 ± 0.925 | 31.797 ± 0.903 | 25.495 ± 0.809 | 17.331 ± 0.700 | 12.645 ± 0.489 | 6.357 ± 0.296 | 1.786 ± 0.079 | 35.975 ± 0.723 | 24.162 ± 0.639 |

| 6h | 89.475 ± 1.465 | 41.378 ± 0.811 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 43.065 ± 0.899 | 20.711 ± 0.845 |

| 6i | 87.560 ± 1.288 | 42.659 ± 0.935 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 37.895 ± 0.735 | 26.505 ± 0.790 |

| Moclobemide | 95.302 ± 2.658 | 83.145 ± 2.311 | 62.435 ± 1.894 | 35.756 ± 1.022 | 24.474 ± 0.997 | 19.635 ± 0.855 | 15.418 ± 0.725 | 12.849 ± 0.518 | 7.251 ± 0.289 | 4.664 ± 0.235 | — | — |

| Clorgyline | 96.381 ± 2.055 | 92.148 ± 1.951 | 88.547 ± 1.816 | 79.115 ± 1.688 | 63.941 ± 1.021 | 35.259 ± 0.903 | 21.718 ± 0.750 | 16.995 ± 0.612 | 11.332 ± 0.484 | 0.048 ± 0.002 | — | — |

| Selegiline | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 98.258 ± 1.052 | 96.107 ± 1.165 |

| Safinamide | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 97.375 ± 2.048 | 94.455 ± 1.274 |

According to the enzyme inhibition results, none of the synthesized compounds showed significant activity against the hMAO-B enzyme. All of the obtained compounds displayed selective inhibition of hMAO-A. At a concentration of 10–3 M, all of the compounds showed more than 50% inhibitory activity. Compounds 6a–6g were able to pass the second step of the enzyme activity assay and their IC50 values were calculated by performing an enzyme inhibition study at concentrations of 10–5–10–11 M. It was shown that the selected compounds displayed a more potent inhibition profile than the reference inhibitor moclobemide (IC50 = 4.664 ± 0.235 μM). Moreover, it was seen that compound 6b showed a similar inhibition profile to that of clorgyline (IC50 = 0.048 ± 0.002 μM). Compound 6b, with the methoxyethyl group bound to nitrogen at the fifth position of the thiadiazole ring, appeared as the most potent MAO-A inhibitor (IC50 = 0.060 ± 0.002 μM), followed by compound 6c, with a propyl substituent (IC50 = 0.241 ± 0.011 μM). The inhibitory activity of the other compounds was determined in the order 6a (ethyl) > 6e (allyl) > 6d (isopropyl), 6f (butyl) > 6g (isobutyl). The replacement of these aliphatic groups with aromatic phenyl (6h) or 4-methylphenyl (6i) groups led to dramatically diminished MAO-A inhibitory activity. Introduction of the propyl group (6c) (IC50 = 0.241 ± 0.011 μM), increased the MAO-A inhibitory activity more than that of the isopropyl group (6d) (IC50 = 1.073 ± 0.051 μM). A similar situation was observed between the compounds with butyl (6f) (IC50 = 1.175 ± 0.050 μM) and isobutyl (6g) groups (IC50 = 1.786 ± 0.079 μM).

2.3. Kinetic studies of enzyme inhibition

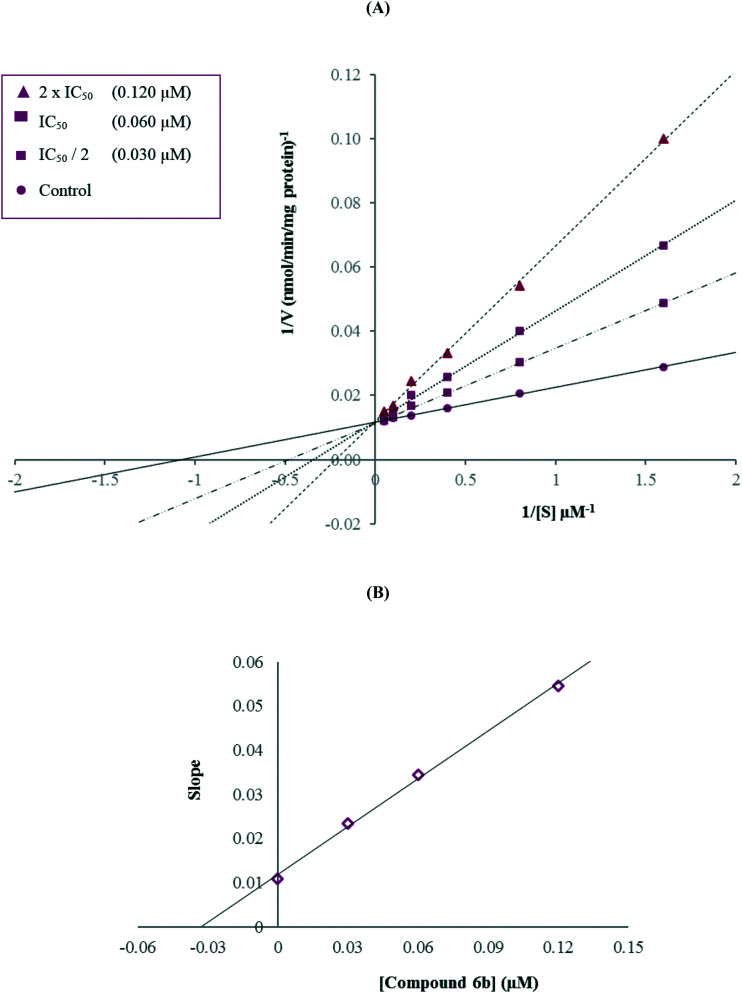

Enzyme kinetic studies were performed to determine the mechanism of hMAO-A inhibition using a procedure similar to that of the MAO inhibition assay. Compound 6b, which was found to be the most potent agent, was included in the enzyme kinetic studies. In order to estimate the type of inhibition of this compound, linear Lineweaver–Burk graphs were used. Substrate velocity curves in the absence and presence of compound 6b were recorded. The secondary plots of slope (Km/Vmax) versus varying concentrations of compound 6b (0, IC50/2, IC50, and 2(IC50)) were created to calculate the Ki (intercept on the x-axis) value of this compound. The graphical analyses of the steady-state inhibition data for compound 6b are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. (A) Lineweaver–Burk plots for the inhibition of hMAO-A by compound 6b. [S], substrate concentration (μM); V, reaction velocity (nmol min–1 mg–1 protein). Inhibitor concentrations are shown at the left. (B) Secondary plot for the calculation of the steady-state inhibition constant (Ki) of compound 6b. Ki was calculated as 0.033 μM.

According to the Lineweaver–Burk plots, a graph that shows parallel lines without any cross-overs is observed for uncompetitive inhibition. For mixed-type inhibition, a graph with lines that do not intersect at the x-axis or the y-axis is formed. Non-competitive inhibition is seen if the lines intersect on the x-axis, and the slopes and y-intercepts are different. In contrast, competitive inhibition has the opposite result, wherein the plotted lines have the same y-intercept, but there are diverse slopes and x-intercepts. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 2, compound 6b was a competitive inhibitor with similar inhibition features to those of the substrates. The Ki value for compound 6b was calculated as 0.033 μM for the inhibition of hMAO-A.

2.4. Reversibility of MAO-A inhibition

The clinical use of irreversible inhibitors has been reported to be limited by some serious cardiovascular or gastrointestinal side effects due to MAO inhibition in the intestine, liver and endothelium.47 Moreover, it is seen that the use of irreversible inhibitors has a disadvantage that the turnover rate of the MAO biosynthesis in the brain reaches normal values at only 40 days, when its use is discontinued. Therefore, it is very important to develop reversible MAO inhibitors with higher selectivity for either one of the isoforms in order to avoid side effects.48 In the present study, the reversibility of MAO-A inhibition by the most active derivative, compound 6b, was determined by using a dialysis method.49–51 Reversible (moclobemide) and irreversible (clorgyline) MAO-A inhibitors were also incubated with the MAO-A enzyme. Table 2 presents the results of reversibility experiments.

Table 2. Reversibility of the inhibition of hMAO-A by compound 6b, moclobemide and clorgyline.

| Compounds incubated with hMAO-A | hMAO-A activity before dialysis (%) | hMAO-A activity after dialysis (%) |

| With no inhibitor | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 |

| Moclobemide | 31.253 ± 0.985 | 90.347 ± 1.895 |

| Clorgyline | 88.315 ± 1.578 | 93.419 ± 1.994 |

| 6b | 25.956 ± 0.951 | 91.508 ± 1.577 |

According to Table 2, the remaining MAO-A activities before dialysis were found as 31.253 ± 0.985% for moclobemide, 88.315 ± 1.578% for clorgyline and 25.956 ± 0.951% for compound 6b. After dialysis, the remaining MAO-A activities for moclobemide and clorgyline were calculated as follows: 90.347 ± 1.895% and 93.419 ± 1.994%, respectively. These results verify that moclobemide is a reversible inhibitor and clorgyline is an irreversible inhibitor of the MAO-A enzyme. It was seen that MAO-A activity was recovered up to 91.508 ± 1.577% after dialysis for compound 6b and this finding indicated that the inhibition by compound 6b was almost completely reversible. It was concluded that this novel reversible inhibitor can have considerable advantages compared to irreversible inhibitors which may possess serious pharmacological side effects.

2.5. Molecular docking studies

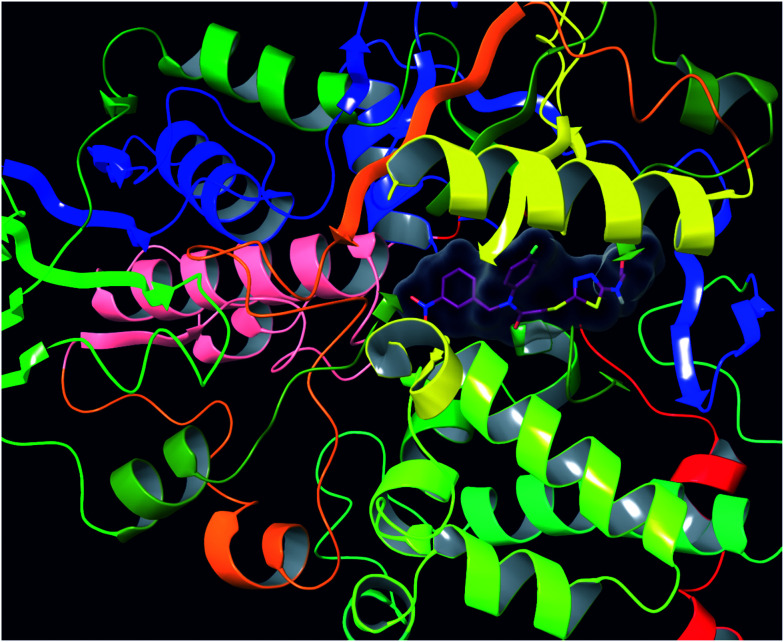

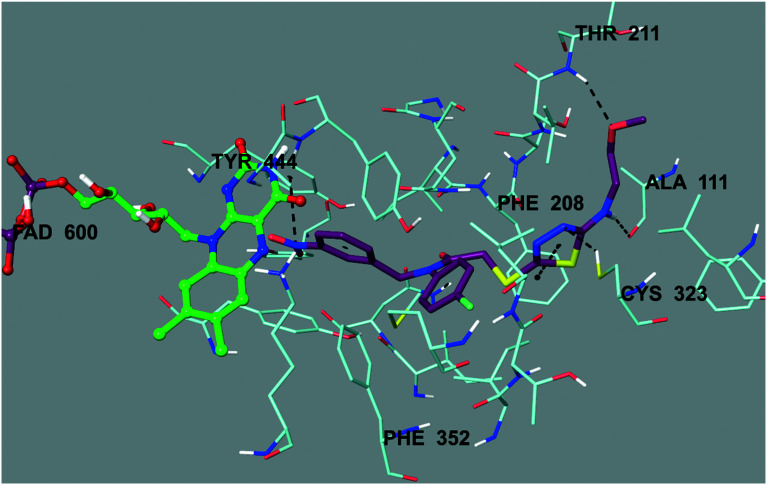

As mentioned in the MAO inhibition assay, compound 6b was found to be the most active derivative in the series against the hMAO-A enzyme. Therefore, docking studies were carried out to evaluate its inhibition capability in silico. Using the X-ray crystal structure of hMAO-A (PDB ID: ; 2Z5X),52 docking studies were performed and the binding modes of compound 6b were assigned. The docking poses of this compound are presented in Fig. 3–6. According to Fig. 3, compound 6b adequately bound to amino acid residues lining the cavity and was located very near the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor.

Fig. 3. The three-dimensional pose of compound 6b in the active region of hMAO-A (PDB ID: ; 2Z5X). This compound is represented by a tube model and colored with maroon.

Fig. 4. The three-dimensional interacting mode of compound 6b in the active region of hMAO-A. The inhibitor and the important residues in the active site of the enzyme are represented by a tube model. The FAD molecule is colored green with a ball and stick model.

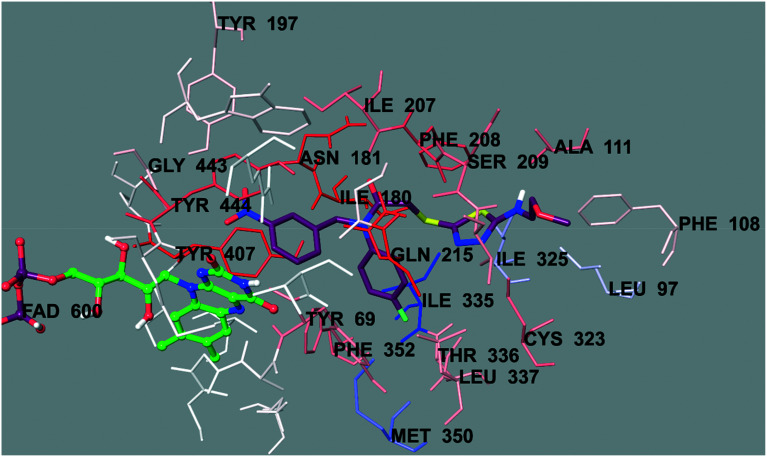

Fig. 5. The van der Waals interaction of compound 6b with the active region of hMAO-A. The active ligand has a lot of favorable van der Waals interactions (red and pink).

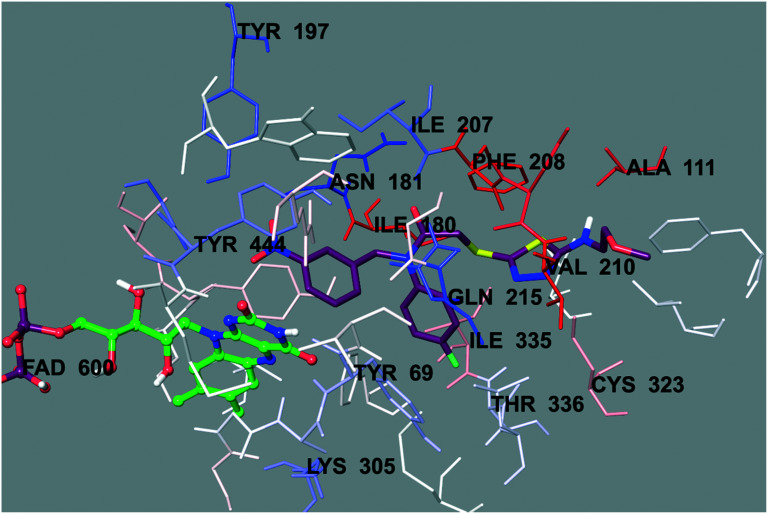

Fig. 6. The electrostatic interaction of compound 6b with the active region of hMAO-A. The residues are colored (blue, red, and pink) according to the distance from the ligand by the Per-Residue Interaction panel.

Fig. 4 presents the 3-dimensional interacting mode of compound 6b in the active region of hMAO-A. When the docking poses of this compound were analyzed, it was clearly seen that there were many types of interactions, such as π–π and cation–π interactions, and the formation of hydrogen bonds. Compound 6b had the nitro group at the 3rd position of the phenyl ring. The nitrogen atom in the nitro group was interacting with the phenyl of Tyr444 by cation–π interaction. Similarly, the 4-fluorophenyl ring near the amide group formed a π–π interaction with the phenyl of Phe352. Another π–π interaction was observed between the 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring and the phenyl of Phe208. Moreover, this 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring created a hydrogen bond via its nitrogen atom. The nitrogen atom formed a hydrogen bond with the –SH of Cys323. Furthermore, it was understood from the docking poses that the methoxyethylamine moiety substituted at the 2nd position of the 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring was very essential for polar interactions. The amino group established a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of Ala111. The oxygen atom of the methoxy moiety at the end of the structure formed another hydrogen bond with the amino of Thr211. Actually, this interaction between the oxygen atom and the amino of Thr211 was an indicator to explain the difference in the enzyme inhibition profiles of the synthesized compounds. It was thought that the substituents, which were capable of the formation of a hydrogen bond, such as the methoxyethyl moiety, strongly contributed to binding to the active site of the enzyme. Thus, this situation could explain why compound 6b exhibited a stronger inhibition profile than the other compounds, because only this compound had such mentioned substituents, which were different from the other compounds in the series.

In order to analyze the contribution of the van der Waals and electrostatic interactions in binding to the enzyme active site, the docking studies were detailed using Glide (Schrödinger Inc., Portland, OR, USA) according to the Per-Residue Interaction panel. Fig. 5 and 6 present the van der Waals and electrostatic interactions of compound 6b. It can be seen that this compound had favorable van der Waals interactions with amino acids Tyr69, Leu97, Phe108, Ala111, Ile180, Asn181, Tyr197, Ile207, Phe208, Ser209, Gln215, Cys323, Ile325, Ile335, Leu337, Thr339, Met350, Phe352, Tyr407, Gly443, and Tyr444; displayed in pink and red (Fig. 5), as described in the Glide user guide.53 Similarly, promising electrostatic contributions of compound 6b were determined with amino acids Tyr69, Ala111, Ile180, Asn181, Tyr197, Ile207, Phe208, Val210, Gln215, Lys305, Cys323, Ile335, Thr336, and Tyr444 (Fig. 6).

2.6. Molecular properties

Computational studies were used to determine whether a particular molecule was similar to known drugs in terms of its physicochemical properties, such as lipophilicity, molecular size, flexibility, and bioavailability. Thereby, in the early discovery, therapeutic opportunities expand through consideration of its suitability to be developed as an oral drug candidate within large numbers of compounds. Prediction of the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of compounds 6a–6i was carried out using QikProp 4.8 software (Schrödinger Inc.),54 which calculates the violations of Lipinski's rule of five55 and Jorgensen's rule of three.56 The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Calculated ADME parameters of compounds 6a–6i.

| Comp. | MW | RB | DM | MV | DHB | AHB | PSA | log P | log S | PCaco | log BB | PMDCK | PM | % HOA | VRF | VRT |

| 6a | 447.501 | 9 | 5.539 | 1305.5 | 1 | 6.5 | 111.04 | 4.117 | –6.094 | 165.361 | –1.729 | 246.297 | 4 | 90.757 | 0 | 1 |

| 6b | 477.527 | 11 | 6.217 | 1398 | 1 | 8.2 | 120.47 | 4.173 | –6.138 | 228.846 | –1.708 | 498.468 | 5 | 93.612 | 0 | 1 |

| 6c | 461.528 | 10 | 13.286 | 1360.3 | 1 | 6.5 | 114.67 | 4.427 | –6.62 | 126.056 | –1.952 | 234.915 | 4 | 90.464 | 0 | 1 |

| 6d | 461.528 | 9 | 9.849 | 1328.1 | 1 | 6.5 | 111.46 | 4.242 | –6.164 | 151.441 | –1.716 | 249.063 | 4 | 90.808 | 0 | 1 |

| 6e | 459.512 | 10 | 4.477 | 1271.5 | 1 | 6.5 | 116.46 | 4.004 | –4.364 | 209.254 | –1.287 | 326.433 | 5 | 91.927 | 0 | 0 |

| 6f | 475.555 | 11 | 7.351 | 1420.4 | 1 | 6.5 | 113.6 | 5.072 | –7.157 | 232.388 | –1.734 | 542.708 | 4 | 86.033 | 1 | 1 |

| 6g | 475.555 | 10 | 14.484 | 1363.6 | 1 | 6.5 | 112.64 | 4.395 | –6.126 | 175.686 | –1.782 | 203.019 | 4 | 92.855 | 0 | 1 |

| 6h | 495.545 | 9 | 13.006 | 1430.2 | 1 | 6.5 | 118.05 | 5.065 | –7.392 | 119.309 | –1.998 | 199.191 | 5 | 80.813 | 1 | 1 |

| 6i | 509.572 | 9 | 8.779 | 1468.8 | 1 | 6.5 | 107.28 | 5.526 | –7.687 | 259.671 | –1.566 | 529.221 | 5 | 76.599 | 2 | 1 |

The computational study for the prediction of the ADME properties of the molecules was performed by determination of the molecular weight (MW), number of rotatable bonds (RB), computed dipole moment (DM), total solvent-accessible volume (MV), estimated number of hydrogen bond donors (DHB), estimated number of hydrogen bond acceptors (AHB), van der Waals surface area of polar nitrogen and oxygen atoms and carbonyl carbon atoms (PSA), predicted octanol/water partition coefficient (log P), predicted aqueous solubility (log S), predicted apparent Caco-2 cell permeability (PCaco), predicted brain/blood partition coefficient (log BB), predicted apparent MDCK cell permeability (PMDCK), number of likely metabolic reactions (PM), predicted human oral absorption percent (% HOA), number of violations of Lipinski's rule of five (VRF) and number of violations of Jorgensen's rule of three (VRT). The molecular weights of all of the compounds were smaller than 500 daltons, except for that of compound 6i. When considering Lipinski's rule of five, most of the compounds had log P values smaller than 5; however, all of the compounds had positive PSA values, DHB values between 0 and 6, and AHB values between 2 and 20. Considering Jorgensen's rule of three, all of the compounds had PCaco values bigger than 22 and PM values between 1 and 8; however, the log S values were smaller than –5.7, except for that of compound 6e.

The prediction of access to the central nervous system (CNS) of the drug molecules is often expressed with log BB. MAO inhibitors regulate local levels of neurotransmitters, and therefore, may be able to pass through the blood–brain barrier (BBB). The log BB values of all of the compounds were within the recommended range of –3 to 1.2. Consequently, most of the compounds were predicted to have a good pharmacokinetic profile and high BBB penetration, which enhanced the biological importance of these compounds in the therapy of certain CNS disorders.

3. Conclusion

Herein, 9 novel 1,3,4-thiadiazole compounds were reported and evaluated for their inhibitory properties towards the hMAO enzymes. All of the compounds were proven to be more selective towards hMAO-A than hMAO-B. For the 7 most potent compounds, the IC50 values were determined against hMAO-A. The IC50 values of the studied compounds were lower (0.060–1.786 μM) when compared to that of the reference, moclobemide (IC50 = 4.664 μM), and compound 6b was selected as the most potent compound (IC50 = 0.060 μM). Moreover, it was seen that compound 6b showed a similar inhibition profile to that of clorgyline (IC50 = 0.048 μM). Further studies revealed that the type of inhibition of this compound was reversible and competitive, and the inhibitory activity of compound 6b was supported by its molecular interactions with hMAO-A. In addition, this compound was predicted to have a good pharmacokinetic profile and high BBB penetration. Based on the results, it was concluded that in the treatment of neurological diseases, as MAO inhibitors, more studies are warranted to increase the clinical potential of this promising class of compounds.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

All chemicals were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Merck Chemicals (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). All melting points (m.p.) were recorded using an Electrothermal 9100 digital melting point apparatus (Electrothermal, Essex, UK) and were uncorrected. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel 60 F254 TLC plates (Merck). Spectroscopic data were registered with the following instruments: IR, Shimadzu 8400S spectrophotometer (Tokyo, Japan); 1H NMR, Bruker DPX 300 NMR spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA), and 13C NMR, Bruker DPX 75 NMR spectrometer (Bruker) in DMSO-d6, using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard; HRMS, Shimadzu LC/MS ITTOF system (Shimadzu).

4.1.1. Synthesis of 4-fluoro-N-(3-nitrobenzylidene)aniline (1)38

3-Nitrobenzaldehyde (33 mmol, 5 g) and 4-fluoroaniline (33 mmol, 4.22 g) were refluxed in ethanol (100 mL) for 8 h with a catalytic amount of glacial acetic acid (0.5 mL). After TLC screening, the mixture was cooled, and the precipitated product was filtered and recrystallized from ethanol. The structural analysis and yield were consistent with the literature values.

4.1.2. Synthesis of 4-fluoro-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)aniline (2)38

To a methanolic (100 mL) solution of compound 1 (20 mmol, 5.21 g), sodium borohydride was added in 4 portions (4 × 0.5 g) at 15 min intervals. After addition, the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 1 h at room temperature. Methanol was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was washed with water, dried and recrystallized from ethanol. The structural analysis and yield were consistent with the literature values.

4.1.3. Synthesis of 2-chloro-N-(4-fluorophenyl)-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (3)38

Chloroacetyl chloride (0.024 mol, 1.91 mL) was added dropwise by stirring into a mixture of compound 2 (0.02 mol, 5.41 g) and triethylamine (0.024 mol, 3.35 mL) in tetrahydrofuran (80 mL) at 0–5 °C. After completion of the dripping, the reaction mixture was stirred for additional 1 h at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the product was washed with water, dried and recrystallized from ethanol. The structural analysis and yield were consistent with the literature values.

4.1.4. Synthesis of 4-substituted thiosemicarbazides (4a–4i)44

A mixture of substituted isothiocyanate (20 mmol) and hydrazine hydrate (40 mmol) in ethanol (50 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 4 h. The precipitated compound was filtered and crystallized from ethanol. The structural analysis and yields were consistent with the literature values.

4.1.5. Synthesis of 5-substituted amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2(3H)-thiones (5a–5i)44

Carbon disulfide (27 mmol, 1.6 mL) was added to a solution of the 4-substituted thiosemicarbazides (4a–4i) and potassium hydroxide in ethanol, and the mixture was refluxed for 10 h. The solution was cooled and acidified to a pH of 4–5 with a hydrochloric acid solution and crystallized from ethanol. The structural analysis and yields were consistent with the literature values.

4.1.6. Synthesis of N-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-substitutedamino-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide derivatives (6a–6i)

A mixture of 5-substituted amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole-2(3H)-thione (5a–5i) (4 mmol) and 2-chloro-N-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-(4-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (3) (4 mmol) in acetone (40 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 8 h in the presence of potassium carbonate (5 mmol, 0.66 g). After evaporation of the acetone, the residue was washed with water and crystallized from ethanol.57

4.1.6.1. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(ethylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6a)

Yield 72%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 1.14 (3H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, CH2–CH[combining low line]3), 3.21–3.26 (2H, m, CH[combining low line]2–CH3), 3.90 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.76 (1H, t, J = 5.2 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 14.64, 38.34, 39.85, 52.31, 117.01 (d, J = 22.7 Hz), 122.78, 123.25, 130.35, 130.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 135.18, 137.72 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 139.72, 148.23, 149.17, 161.82 (d, J = 245.8 Hz), 167.59, 169.81. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C19H18FN5O3S2: 448.0908; found 448.0891.

4.1.6.2. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-((methoxyethyl)amino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6b)

Yield 71%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 3.26 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.41 (2H, t, J = 5.0 Hz, CH2), 3.45–3.49 (2H, m, CH2), 3.89 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.60 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.87 (1H, t, J = 5.3 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 38.27, 44.40, 52.30, 58.41, 70.40, 117.02 (d, J= 22.8 Hz), 122.80, 123.26, 130.38, 130.90 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 135.19, 137.73 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 139.73, 148.25, 149.57, 161.82 (d, J = 244.7 Hz), 167.58, 169.75. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H20FN5O4S2: 478.1014; found 478.0995.

4.1.6.3. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(propylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6c)

Yield 79%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 0.88 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3), 1.48–1.60 (2H, m, CH3–CH[combining low line]2–CH2–), 3.14–3.20 (2H, m, CH3–CH2–CH[combining low line]2–), 3.89 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.78 (1H, t, J = 5.4 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 11.81, 22.21, 38.34, 46.82, 52.31, 117.01 (d, J = 22.6 Hz), 122.79, 123.26, 130.36, 130.90 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 135.19, 137.72 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 139.73, 148.24, 149.05, 161.82 (d, J = 246.0 Hz), 167.60, 170.02. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H20FN5O3S2: 462.1064; found 462.1044.

4.1.6.4. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(isopropylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6d)

Yield 74%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 1.15 (6H, d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2CH3), 3.68–3.79 (1H, m, CH), 3.89 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.68–7.70 (2H, m, Ar–H and NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 22.56, 38.34, 46.96, 52.29, 117.01 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 122.79, 123.25, 130.36, 130.90 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 135.19, 137.71 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 139.72, 148.24, 149.03, 161.82 (d, J = 245.2 Hz), 167.60, 168.98. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H20FN5O3S2: 462.1064; found 462.1043.

4.1.6.5. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(allylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6e)

Yield 63%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 3.85–3.90 (4H, m, CH2 CH–CH[combining low line]2 and CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 5.10–5.25 (2H, m, CH[combining low line]2 CH–CH2), 5.82–5.94 (1H, m, CH2 CH[combining low line]–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.94 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 38.34, 47.11, 52.32, 116.64, 117.02 (d, J = 22.8 Hz), 122.79, 123.25, 130.37, 130.89 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 134.76, 135.19, 137.72 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 139.72, 148.24, 149.76, 161.82 (d, J = 244.8 Hz), 167.57, 168.79. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C20H18FN5O3S2: 460.0908; found 460.0890.

4.1.6.6. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(butylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6f)

Yield 62%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 0.88 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, CH3), 1.26–1.38 (2H, m, CH2), 1.46–1.55 (2H, m, CH2), 3.17–3.24 (2H, m, CH2), 3.89 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.76 (1H, t, J = 5.4 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 14.08, 19.99, 30.98, 38.34, 44.70, 52.29, 117.01 (d, J = 22.3 Hz), 122.79, 123.26, 130.36, 130.90 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 135.19, 137.72 (d, J = 2.9 Hz), 139.73, 148.24, 149.04, 161.82 (d, J = 246.0 Hz), 167.59, 169.97. HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H22FN5O3S2: 476.1221; found 476.1213.

4.1.6.7. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(isobutylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6g)

Yield 81%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 0.88 (6H, d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2CH3), 1.78–1.91 (1H, m, CH), 3.02–3.06 (2H, m, CH2), 3.89 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.00 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.24 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.32–7.37 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.59 (1H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 7.81 (1H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NH), 8.07–8.12 (2H, m, Ar–H). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 20.49, 27.94, 38.33, 52.30, 52.63, 117.01 (d, J = 22.7 Hz), 122.78, 123.26, 130.35, 130.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz), 135.19, 137.72 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 139.72, 148.24, 149.00, 161.82 (d, J = 246.0 Hz), 167.60, 170.16 (C O). HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H22FN5O3S2: 476.1221; found 476.1210.

4.1.6.8. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(phenylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6h)

Yield 74%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 4.02 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.02 (2H, s, N–CH2), 6.99 (1H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, Ar–H), 7.23–7.41 (6H, m, Ar–H), 7.54–7.62 (3H, m, Ar–H), 7.71 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 8.09–8.12 (2H, m, Ar–H), 10.35 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 38.18, 52.36, 117.07 (d, J = 22.8 Hz), 117.80, 122.41, 122.81, 123.27, 129.56, 130.35, 130.93 (d, J = 8.9 Hz), 135.20, 137.71 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 139.71, 140.82, 148.25, 152.57, 161.87 (d, J = 245.8 Hz), 165.15, 167.45 (C O). HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H18FN5O3S2: 496.0908; found 496.0891.

4.1.6.9. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-[(5-(4-methylphenylamino)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)thio]-N-(3-nitrobenzyl)acetamide (6i)

Yield 67%. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 2.24 (3H, s, CH3), 4.01 (2H, s, CO–CH2), 5.02 (2H, s, N–CH2), 7.13 (2H, d, J = 8.3 Hz, Ar–H), 7.26 (2H, t, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar–H), 7.36–7.41 (2H, m, Ar–H), 7.44 (2H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, Ar–H), 7.59 (2H, t, J = 7.9 Hz, Ar–H), 7.71 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, Ar–H), 8.08–8.13 (2H, m, Ar–H), 10.25 (1H, s, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6, ppm) δ 20.82, 38.22, 52.35, 117.06 (d, J = 23.0 Hz), 117.92, 122.81, 123.26, 129.94, 130.35, 130.93 (d, J = 9.0 Hz), 131.39, 135.20, 137.70 (d, J = 2.8 Hz), 138.45, 139.71, 148.24, 152.06, 161.86 (d, J = 246.2 Hz), 165.36, 167.46 (C O). HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H20FN5O3S2: 510.1064; found 510.1047.

4.2. MAO inhibition assay

The MAO inhibition potency of the synthesized compounds was determined according to the assay reported in our recent study.40 In the enzymatic assay, three different daily prepared solutions were used. I) Inhibitor solutions: Synthesized compounds and reference agents were prepared in 2% DMSO in 10–3–10–11 M concentrations. II) Enzyme solutions: Recombinant hMAO-A (0.5 U mL–1) and recombinant hMAO-B (0.64 U mL–1) enzymes were dissolved in phosphate buffer and the final volumes were adjusted to 10 mL. III) Working solution: Horseradish peroxidase (200 U mL–1, 100 μL), Ampliflu™ red (20 mM, 200 μL) and tyramine (100 mM, 200 μL) were dissolved in phosphate buffer and the final volume was adjusted to 10 mL.

The solutions of inhibitors (20 μL per well) and hMAO-A (100 μL per well) or hMAO-B (100 μL per well) were added to a black flat-bottom 96-well micro test plate, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After this incubation period, the reaction was started by adding a working solution (100 μL per well). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and the fluorescence (Ex/Em = 535/587 nm) was measured at 5 min intervals. Control experiments were carried out simultaneously by replacing the inhibitor solution with 2% DMSO (20 μL). To check the probable inhibitory effect of the inhibitors on horseradish peroxidase, a parallel reading was performed by replacing the enzyme solutions with a 3% H2O2 solution (20 mM, 100 μL per well). In addition, the possible capacity of the inhibitors to modify the fluorescence generated in the reaction mixture due to non-enzymatic inhibition was determined by mixing the inhibitor and working solutions.

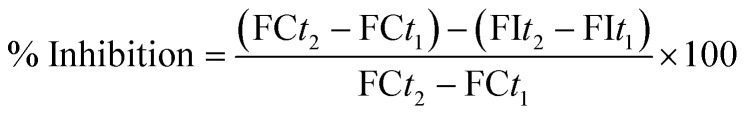

The specific fluorescence emission that was used to obtain the final results was calculated after subtraction of the background activity, which was determined from vials containing all of the components, except the hMAO isoforms, which were replaced by a phosphate buffer (100 μL per well). The blank, control, and all of the concentrations of the inhibitors were analyzed in quadruplicate and the percent of inhibition was calculated using the following equation: FCt2: fluorescence of a control well measured at time t2; FCt1: fluorescence of a control well measured at time t2; FIt2: fluorescence of an inhibitor well measured at time t2; FIt1: fluorescence of an inhibitor well measured at time t1. The IC50 values were calculated from a dose–response curve obtained by plotting the percentage inhibition versus the log concentration with the use of GraphPad ‘PRISM’ software (version 5.0). The results were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

FCt2: fluorescence of a control well measured at time t2; FCt1: fluorescence of a control well measured at time t2; FIt2: fluorescence of an inhibitor well measured at time t2; FIt1: fluorescence of an inhibitor well measured at time t1. The IC50 values were calculated from a dose–response curve obtained by plotting the percentage inhibition versus the log concentration with the use of GraphPad ‘PRISM’ software (version 5.0). The results were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

4.3. Kinetic studies of enzyme inhibition

A protocol similar to that of the MAO inhibition assay was followed using the same materials. The most active compound, 6b, was tested at concentrations of IC50/2, IC50, and 2(IC50). The solutions of compound 6b (20 μL per well) and the MAO-A (0.5 U mL–1, 100 μL per well) enzyme were added to a black flat-bottomed 96-well micro test plate, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Once incubation was completed, the working solution, comprising various concentrations (20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 μM) of substrate (100 μL per well), was added. The increase of the fluorescence (Ex/Em = 535/587 nm) was recorded for 30 min. A parallel experiment was carried out without an inhibitor. All of the experiments were performed in quadruplicate. The experimental data were analysed as Lineweaver–Burk plots using Microsoft Office Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The Km/Vmax (slope) values of the Lineweaver–Burk plots were re-plotted versus the inhibitor concentration to determine the Ki values from the x-axis intercept as –Ki.

4.4. Reversibility of MAO-A inhibition

Reversibility of the MAO-A inhibition with compounds (moclobemide, clorgyline and compound 6b) was determined by a dialysis method previously described.49–51 Dialysis tubing 16 × 25 mm (Sigma, Germany) with a molecular weight cut-off of 12 000 Da and a sample capacity of 0.5–10 mL was used. Adequate amounts of the recombinant hMAO-A enzyme (1 U mL–1) and compound 6b at a concentration equal to four fold the IC50 values, for the inhibition of hMAO-A, were incubated in potassium phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.4, 5% sucrose containing 1% DMSO) for 15 min at 37 °C. Other sets were prepared by preincubation of the same amount of hMAO-A with the reference inhibitors. Enzyme–inhibitor mixtures were subsequently dialyzed at 4 °C in 80 mL of dialysis buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 5% sucrose). The dialysis buffer was replaced with fresh buffer two times during the 24 h of dialysis. After dialysis, residual MAO-A activities were measured. All reactions were carried out in triplicate and the residual enzyme activity was expressed as mean ± SEM. For comparison, undialyzed mixtures of MAO-A and the inhibitors were included in the study.

4.5. Molecular docking studies

A structure-based in silico procedure was applied to discover the binding modes of compound 6b to the hMAO-A enzyme active site. The crystal structures of hMAO-A (PDB ID: ; 2Z5X),52 which was crystallized with harmine, were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank server (; www.pdb.org).

The structures of the ligands were built using the Schrödinger Maestro58 interface and were then submitted to the Protein Preparation Wizard protocol of the Schrödinger Suite 2016 Update 2.59 The ligands were prepared using LigPrep 3.8 (Schrödinger Inc.)60 to correctly assign the protonation states at a pH of 7.4 ± 1.0 and the atom types. Bond orders were assigned, and hydrogen atoms were added to the structures. The grid generation was performed using Glide 7.1.53 The grid box, with dimensions of 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å, was cantered in the vicinity of the FAD N5 atom on the catalytic site of the protein to cover all of the binding sites and neighbouring residues.61–63 Flexible docking runs were performed in single-precision docking mode (SP).

4.6. Molecular properties

Physicochemical properties of the compounds were predicted through QikProp 4.8 software.54

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0md00150c

References

- Chavarria D., Fernandes C., Silva V., Silva C., Gil-Martins E., Soares P., Silva T., Silva R., Remiao F., Oliveira P. J., Borges F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;185:111770. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parambi D. G. T., Oh J. M., Baek S. C., Lee J. P., Tondo A. R., Nicolotti O., Kim H., Mathew B. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;93:103335. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hong R. Y., Guo M., Liu Y., Chen N., Li X., Kong D. X. Molecules. 2019;24:4003. doi: 10.3390/molecules24214003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari B., Jalil S., Zaib S., Safarov S., Khalikova M., Khalikov D., Ospanov M., Yelibayeva N., Zhumagalieva S., Abilov Z. A., Turmukhanova M. Z., Kalugin S. N., Salman G. A., Ehlers P., Hameed A., Iqbal J., Langer P. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4:13760–13767. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Xiong J., Guan H. D., Wang C. H., Lei X., Hu J. F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019;27:2027–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetnev A., Shlenev R., Efimova J., Ivanovskii S., Tarasov A., Petzer A., Petzer J. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:126677. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao K., Endo S., Nagai J., Kamauchi H., Takemura Y., Uesawa Y., Sugita Y. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;92:103285. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao K., Kamauchi S. U. H., Sugita Y. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;87:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar Çevik U., Osmaniye D., Sağlik B. N., Levent S., Kaya Çavuşoğlu B., Özkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2019;56:3000–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Chirkova Z. V., Kabanova M. V., Filimonov S. I., Abramov I. G., Petzer A., Hitge R., Petzer J. P., Suponitsky K. Y. Drug Dev. Res. 2019;80:970–980. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo M. L., Christodoulou M. S., Calogero A. M., Pinzi L., Rastelli G., Passarella D., Cappelletti G., Dalla Via L. ChemMedChem. 2019;14:1641–1652. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201900261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lv X., Cheng K., Tian Y., Huang X., Kong H., Duan Y., Han J., Liao C., Xie Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:1090–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpitimpiti A. N., Petzer J. P., Petzer A., Jordaan J. H. L., Lourens A. C. U. Mol. Diversity. 2019;23:897–913. doi: 10.1007/s11030-019-09917-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby R., Petzer J. P., Petzer A., Ashraf U. M., Atari E., Alasmari F., Kumarasamy S., Sari Y., Khalil A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019;34:863–876. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1593158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qhobosheane M. A., Petzer A., Petzer J. P., Legoabe L. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:5531–5537. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Z., Wang K., Shi J., Liu W., Tan Z. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;178:726–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. M., Kang M. G., Hong A., Park J. E., Kim S. H., Lee J. P., Baek S. C., Park D., Nam S. J., Cho M. L., Kim H. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;137:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar B., Kumar V., Prashar V., Saini S., Dwivedi A. R., Bajaj B., Mehta D., Parkash J., Kumar V. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;177:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N., Mishra P. Med. Chem. Res. 2019;28:1488–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N., Mishra P. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019;79:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam M. H., Park M., Park H., Kim Y., Yoon S., Sawant V. S., Choi J. W., Park J. H., Park K. D., Min S. J., Lee C. J., Choo H. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:1519–1529. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis J., Cagide F., Chavarria D., Silva T., Fernandes C., Gaspar A., Uriarte E., Remiao F., Alcaro S., Ortuso F., Borges F. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5879–5893. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert J., Foka G. B., Repsold B. P., Oliver D. W., Kapp E., Malan S. F. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;125:853–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muğlu H., Yakan H., Shouaib H. A. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1203:127470. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wang X., Yang J., Guo L., Wang X., Song B., Dong W., Wang W. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;186:111897. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Enany W. A. M. A., Gomha S. M., El-Ziaty A. K., Hussein W., Abdulla M. M., Hassan S. A., Sallam H. A., Ali R. S. Synth. Commun. 2019;50:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Giray B., Karadag A. E., Ipek O. S., Pekel H., Guzel M., Kucuk H. B. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;95:103509. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali J. K., Sutar Y. B., Pahelkar A. R., Verma P. M., Telvekar V. N. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020;95:174–181. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. F., Verma G., Akhtar W., Shaquiquzzaman M., Akhter M., Rizvi M. A., Alam M. M. Arabian J. Chem. 2019;12:5000–5018. [Google Scholar]

- Brai A., Ronzini S., Riva V., Botta L., Zamperini C., Borgini M., Trivisani C. I., Garbelli A., Pennisi C., Boccuto A., Saladini F., Zazzi M., Maga G., Botta M. Molecules. 2019;24:3988. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okla M. K., Alamri S. A., Alaraidh I. A., Al-ghamdi A. A., Soufan W. H., Allam A. A., Fouda M. M. G., Gaffer H. E. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4:11735–11739. [Google Scholar]

- Er M., Özer A., Direkel Ş., Karakurt T., Tahtaci H. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1194:284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Abo-Ashour M. F., Eldehna W. M., Nocentini A., Ibrahim H. S., Bua S., Abdel-Aziz H. A., Abou-Seri S. M., Supuran C. T. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;87:794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujan R., Saeed A., Channar P. A., Larik F. A., Abbas Q., Alajmi M. F., El-Seedi H. R., Rind M. A., Hassan M., Raza H., Seo S. Y. Molecules. 2019;24:860. doi: 10.3390/molecules24050860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Rodríguez M. A., Gu W., Silverman R. B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:4423–4430. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A. K., Edmondson D. E. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3928–3935. doi: 10.1021/bi9002106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi R. K., Goshain O., Ayyannan S. R. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:462–474. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgın S., Osmaniye D., Levent S., Sağlık B. N., Acar Çevik U., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Özkay Y., Kaplancıklı Z. A. Molecules. 2017;22:2187. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya B., Yurttaş L., Sağlik B. N., Levent S., Özkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017;32:193–202. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1247054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavusoglu B. K., Saglik B. N., Osmaniye D., Levent S., Acar Cevik U., Karaduman A. B., Ozkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. Molecules. 2017;23:60. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çavuşoğlu B. K., Sağlık B. N., Özkay Y., İnci B., Kaplancıklı Z. A. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;76:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sağlık B. N., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Osmaniye D., Levent S., Çevik U. A., Ilgın S., Özkay Y., Kaplancıklı Z. A., Öztürk Y. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;85:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar Çevik U., Osmaniye D., Sağlik B. N., Levent S., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Karaduman A. B., Özkay Ü. D., Özkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A., Turan G. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2020;57:2225–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Çevik U. A., Osmaniye D., Sağlik B. N., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Levent S., Karaduman A. B., Ilgin S., Karaburun A. Ç., Özkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. Med. Chem. Res. 2020;29:1000–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Turan G., Osmaniye D., Sağlik B. N., Çevik U. A., Levent S., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Özkay Ü. D., Özkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2020;195(6):491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya B., Saglik B. N., Levent S., Ozkay Y., Kaplancikli Z. A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016;31:1654–1661. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2016.1161621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youdim M. B., Edmondson D., Tipton K. F. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:295–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostert S., Petzer A., Petzer J. P. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2016;87:737–746. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzer A. Life Sci. 2013;93:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew B., Mathew G. E., Ucar G., Joy M., Nafna E. K., Lohidakshan K. K., Suresh J. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;104:1321–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol Gunal S., Teke Tuncel S., Gokhan Kelekci N., Ucar G., Yuce Dursun B., Sag Erdem S., Dogan I. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;77:608–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S. Y., Ma J., Kondou Y., Yoshimura M., Yamashita E., Tsukihara T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:5739–5744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710626105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glide, version 7.1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016.

- QikProp, version 4.8, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016.

- Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Duffy E. M. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çevik U. A., Osmaniye D., Levent S., Sağlik B. N., Çavuşoğlu B. K., Özkay Y., Kaplancikl Z. A. Heterocycl. Commun. 2020;26:6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maestro, version 10.6, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016.

- Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016.

- LigPrep, version 3.8, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016.

- Toprakci M., Yelekci K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:4438–4446. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhan-Kelekci N., Simsek O. O., Ercan A., Yelekci K., Sahin Z. S., Isik S., Ucar G., Bilgin A. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6761–6772. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evranos-Aksoz B., Yabanoglu-Ciftci S., Ucar G., Yelekci K., Ertan R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:3278–3284. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.