Abstract

Feraheme (ferumoxytol), a negatively charged, carboxymethyl dextran-coated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle (USPIO, 30 nm, −16 mV), is clinically approved as an iron supplement and is used off-label for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of macrophage-rich lesions, but the mechanism of recognition is not known. We investigated mechanisms of uptake of Feraheme by various types of macrophages in vitro and in vivo. The uptake by mouse peritoneal macrophages was not inhibited in complement-deficient serum. In contrast, the uptake of larger and less charged SPIO nanoworms (60 nm, −5 mV; 120 nm, −5 mV, respectively) was completely inhibited in complement deficient serum, which could be attributed to more C3 molecules bound per nanoparticle than Feraheme. The uptake of Feraheme in vitro was blocked by scavenger receptor (SR) inhibitor polyinosinic acid (PIA) and by antibody against scavenger receptor type A I/II (SR-AI/II). Antibodies against other SRs including MARCO, CD14, SR-BI, and CD11b had no effect on Feraheme uptake. Intraperitoneally administered PIA inhibited the peritoneal macrophage uptake of Feraheme in vivo. Nonmacrophage cells transfected with SR-AI plasmid efficiently internalized Feraheme but not noncharged ultrasmall SPIO of the same size (26 nm, −6 mV), suggesting that the anionic carboxymethyl groups of Feraheme are responsible for the SR-AI recognition. The uptake by nondifferentiated bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) and by BMDM differentiated into M1 (proinflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) types was efficiently inhibited by PIA and anti-SR-AI/II antibody. Interestingly, all BMDM types expressed similar levels of SR-AI/II. In conclusion, Feraheme is efficiently recognized via SR-AI/II but not via complement by different macrophage types. The recognition by the common phagocytic receptor has implications for specificity of imaging of macrophage subtypes.

Keywords: scavenger receptor, iron oxide, nanoworms, macrophage, bone marrow, uptake

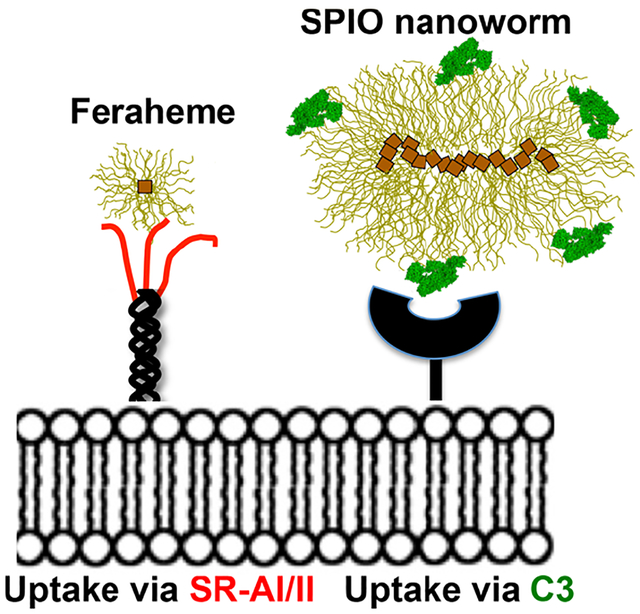

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Macrophages play some of the most important functions in innate immune responses and are involved in pathogenesis of hundreds of diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and arthritis.1 Depending on their microenvironment, macrophages can be differentially programmed into either a pro-inflammatory type (M1) characterized by expression of iNOS and secretion of IFN-γ and TNF-α or into an anti-inflammatory type (M2) characterized by expression of CD163 and CD206 and secretion of IL-4, IL-10, and CSF-1.2 The distinction between M1 and M2 types is somewhat artificial as there is a substantial plasticity depending on molecular expression profile and response to different chemokines and cytokines.3

There is an extensive effort to interrogate the phenotype of disease-associated macrophages via different imaging modalities with the hope that profiling of macrophages can help guide treatments and understand disease biology.4 A notable example is cancer where the inflammatory state of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) plays a critical role in therapy response.5 Additionally, macrophage reprogramming is an emerging therapeutic strategy.6 Of all imaging modalities, MRI appears to be the most versatile due to its excellent anatomical and spatial resolution, tissue contrast, and decreasing cost. Superparamagnetic iron oxides (SPIOs) are nanoparticle-based MRI contrast agents that consist of magnetite-maghemite (Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3) crystals and surrounded by a polymer coat.7 When SPIO accumulate in tissues and cells, they reduce transverse relaxation time T2 resulting in increased magnetic susceptibility and darkening of the T2- and T2*-weighted images.8–10 Just like any other nanoparticle, SPIOs exhibit affinity toward macrophages,11–14 which was exploited in (now discontinued) dextran-coated SPIOs (Resovist, Feridex, Combidex) that were designed to accumulate in macrophages and other phagocytic cells in the liver and lymph nodes. Feraheme (ferumoxytol) was developed by Advanced Magnetics (now AMAG Pharmaceuticals) as a strategic decision to move away from contrast media into therapeutic applications. Feraheme represents a redesign in the dextran coating by employing reduced carboxymethyl dextran that resulted in enhanced stability, uniform particle size, and an improved safety profile compared to previous SPIOs. While Feraheme is a blockbuster drug with over $1 billion sales for anemia treatment, the common sentiment in diagnostic radiology is that there is a need for a T2MRI contrast agent for imaging macrophage-rich lesions.15,16 Many basic research and clinical groups are currently exploring Feraheme for imaging macrophages in cancer, stroke, inflammation, and autoimmune disorders.16,17 Several groups report a correlation between Feraheme uptake by TAMs, therapeutic response, and cancer stage.18,19 Due to the large number of carboxymethyl groups (over 500 per NP), Feraheme can be covalently or noncovalently modified with drugs and fluorophores for multi-modal imaging and theranostics.20,21 Furthermore, there are indications that Feraheme leads to improved therapeutic response and macrophage reprogramming.22

Despite the wealth of data on the uptake of Feraheme by macrophages and the utility of Feraheme for preclinical and clinical imaging, it is surprising that no attempt has been made to understand the mechanisms of uptake. Our previous studies with larger (60–120 nm) SPIO nanoworms (NWs) indicate that a complement plays an important role in the uptake by macrophages and neutrophils.23–26 Here, we set out to identify mechanisms of uptake of Feraheme by different macrophage types. Our results show that the scavenger receptor type AI/II is the predominant receptor responsible for uptake by peritoneal and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) differentiated into M1 and M2 type in vitro, and plays a critical role in the uptake by peritoneal macrophages (PMs) and spleen macrophages in vivo. Our data also indicate that SR-AI/II is ubiquitously expressed on both M1 and M2 types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Feraheme (lot 10021802) was provided by Dr. Serkova. SPIO nanoparticles were synthesized from either 10 kDa reduced dextran or 15–25 kDa native dextran (Sigma-Aldrich) and Fe(III) chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) or Fe(II) chloride (Fisher) by a modified Molday precipitation method in ammonia, as described by us previously.27 Dextran/Fe ratio in the reaction was used to control the nanoparticle size. Nanoparticles were resuspended in sterile water, filtered through 0.22 μm filter and stored at 4 °C. The size and zeta potential of nanoparticles were determined using Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments). Polyinosinic acid (PIA, catalog# P4154–25MG) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, catalog# L2630) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant mouse interleukin-4 (IL-4, catalog# 574304), recombinant mouse interferon-gamma (IFN-γ, catalog# 575306), AlexaFluor 594 antimouse iNOS2 antibody (Catalog# 696804), FITC antimouse/human CD11b (catalog# 101206), rat antimouse CD14 (catalog # 123301), rat antimouse CD16/32 (as the mouse Fc-gamma receptor blocker, catalog# 101302), and FITC-labeled rabbit antimouse CD163/M130 antibody (catalog# bs-2527R-FITC) were purchased from BioLegend. Rabbit antimouse arginase I (H-52, catalog# sc-20150) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Goat antimouse scavenger receptor AI/II (SR-AI/II) (catalog# AF1797) was purchased from R&D Systems (Bio-Techne Corporation). Rat antimouse MARCO (macrophage receptor with collagenous domain) (catalog# MCA 1848) was purchased from Bio-Rad AbD Serotec Ltd. Rabbit antimouse scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) antibody (catalog# AJ1734a) was purchased from Abgent (San Diego, CA). Rat antimouse CD11b antibody (catalog# 553308) was purchased from BD Biosciences. AlexaFluor 594 donkey antigoat secondary antibody (catalog# A-11058), AlexaFluor 647 chicken antigoat secondary antibody (catalog# A-21469), and AlexaFluor 594 goat antirabbit secondary antibody (catalog# A-11012), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, catalog# 10–017-CV), Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (catalog# 10–040-CV), F-12K medium (catalog# 10–025-CV), fetal bovine serum (FBS, catalog# 26140–079), penicillin–streptomycin (Pen–Strep, catalog# 30–002-CL), and Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (catalog# L3000001) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Paraformaldehyde (catalog# P6148–500G) and horse serum (catalog# H0146–10 ML) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Bovine serum albumin (BSA, catalog# 0219989880) was purchased from MP Biomedicals.

Immuno Dot-Blot Assay of Complement C3 Deposition.

Nanoparticles were incubated with mouse serum with or without 10 mM EDTA (inhibitor of all pathways). The immuno-dot assay was performed to measure the mouse complement component 3 (C3) according to our previous report.28 Briefly, 1 mg/mL (Fe) was incubated with freshly thawed mouse serum at a 1:3 volume ratio for 30 min at 37 °C. Particles were washed three times with PBS at 450,000g for 10 min at 4 °C in a Beckman Optima TLX ultracentrifuge equipped with a TLA-100.3 rotor. The pellets were resuspended in PBS, and 2 μL of sample was applied in triplicates onto a 0.45 μm pore nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were probed with the primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and then incubated with the IRDye 800CW-labeled secondary antibody. The membrane was scanned using Odyssey infrared imager (Li-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, US) at 800 nm. The integrated intensities of dots in the scanned images were determined from 8-bit grayscale images using ImageJ software. The quantification data were plotted using Prism software v. 6.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Cell Culture and Plasmid Transfection.

Mouse peritoneal macrophages (PMs) and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) were isolated from female or male BALB/c mice (no differences were observed in the results). PMs were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen–Strep under 5% CO2 in a 37 °C incubator. BMDMs were isolated from the C57/BL6 or BALB/c male or female mice (6–10 week old) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% L929-conditioned medium, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, and 1% Pen–Strep under 10% CO2 in a 37 °C incubator. BMDMs were induced into M1 using LPS (0.1 μg/mL) and IFN-γ (0.02 μg/mL) or into M2 using IL-4 (0.02 μg/mL) in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% Pen–Strep. Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO-K1) cells were maintained in F-12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen–Strep under 5% CO2 in a 37 °C incubator. Scavenger receptor plasmid expressing SR-AI under the CMV promoter was isolated from E. coli (transfected with the plasmids) using QIAprep Miniprep kit (Catalog# 27104, QIAGEN). CHO-K1 cells were transfected with the plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The details of the plasmids were described in full detail in our previous publication.26

Flow Cytometry.

Macrophages were first incubated with rat antimouse CD16/32 antibody (as the mouse Fc-gamma blocker) and then stained with FITC antimouse/human CD11b and goat antimouse SR-AI (detected with AlexaFluor 647 chicken antigoat secondary antibody) in 1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide in 1× PBS. Cells were resuspended at ~0.5 million/mL and 20,000 events were acquired with Guava EasyCyte HT flow cytometer (Merck KGaA). The data were analyzed and plotted using FlowJo version 10.

In Vitro Uptake of Nanoparticle and Cell Staining.

Mouse PMs and BMDM were plated in 96-well plates. PMs and three types of BMDM including M0, M1, and M2 were incubated with Feraheme at 0.1 mg/mL in the presence of wild type (WT) mouse serum with or without PIA 20 μg/mL as the final incubation concentration, C3 knockout (KO) mouse serum with or without PIA, serum-free medium with or without PIA, and different scavenger receptor antibodies, including anti-SR-AI/II, anti-SR-BI, anti-MARCO, and anti-CD14. All these antibodies were preincubated with cells at 20 μg/mL as the final incubation concentration for 30 min before addition of nanoparticles to cells. CHO cells transfected with scavenger receptor were incubated with Feraheme or USPIO at 0.1 mg Fe/mL in culture medium with or without PIA. After the incubation with nanoparticles, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. Cells were stained using Prussian blue to detect nanoparticle uptake and counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red (Sigma).

For immunofluorescence, macrophages were stained with AlexaFluor 594 antimouse iNOS2 antibody (M1 marker) or rabbit antimouse arginase I antibody (M2 marker, stained with AlexaFluor 594 Goat anti-Rabbit secondary antibody), or with FITC antimouse/human CD11b antibody and goat antimouse SR-AI antibody (stained with Alexa Fluor 594 donkey antigoat secondary antibody). The cells were incubated with rat antimouse CD16/32 antibody (1:1000 dilution), 10% horse serum in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS and then stained with primary antibody (1:500 dilution) and secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution) in PBS with 0.5% BSA and 0.1% Tween20.

In Vivo Uptake of Nanoparticle and Histology.

The animal studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Colorado. Wild-type BALB/c mice were bred in house. For in vivo uptake of Feraheme by PMs, PBS (25 μL), or PIA (25 μL, 2 mg/mL) were mixed with Feraheme (25 μL, 4 mg/mL) and then injected intraperitoneally to 8-week-old male mice. PMs were collected 6 h postinjection and washed to remove excess nanoparticles and then plated in a 96-well plate. After overnight settlement, PMs were fixed using 4% solution of paraformaldehyde and stained with Prussian blue.

Cell Imaging and Quantification.

Fluorescent images of macrophages were acquired using a Zeiss AxioObserver 5 fluorescence microscope or a Nikon AR1 confocal laser microscope. Prussian blue stained cell images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse light microscope equipped with a color camera. In order to quantify the blue color inside the cells, TIFF RGB images of the stained cells were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope under the same magnification. At least 5 microscopical fields were acquired per well, from at least 2 experimental replicates, and also of control cells not incubated with nanoparticles. The images were opened in ImageJ, converted into YUV color space and thresholded for blue and green components using Threshold Color plugin. Then, the images were converted into a 16-bit gray scale and inverted. The mean fluorescence value above threshold was measured for each image. The gray value average and standard deviation (after subtracting the control cell values) were plotted with Prism. Statistical significance of quantitative data between groups was determined using an unpaired, two-tailed t test. P values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Scavenger Receptor SR-AI/II, but Not Complement, Mediates Recognition of Feraheme by Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages.

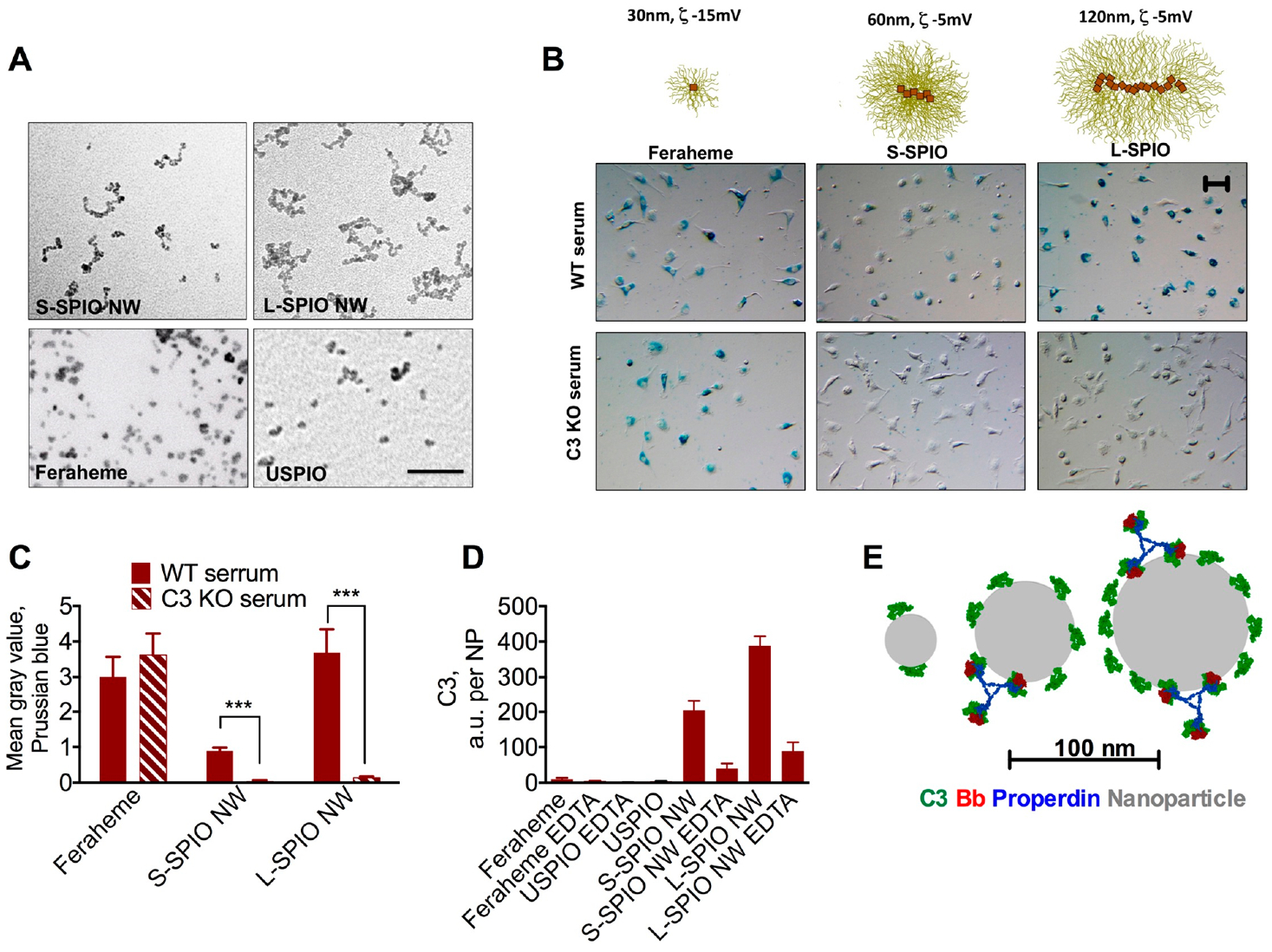

We prepared small (60 nm) SPIO NWs, large (120 nm) SPIO NWs, and USPIO (30 nm). TEM images of all particles used in the study are shown in Figure 1A. In order to understand the role of the complement in the uptake of Feraheme, we isolated nonactivated peritoneal macrophages (PMs) from BALB/c mice and exposed them to 0.1 mg Fe/mL Feraheme, 60 nm (small) S-SPIO NW, and 120 nm (large) L-SPIO NW for 3–6 h in the presence of wild type (WT) mouse sera or sera deficient for complement C3. Prussian blue staining (Figure 1B) and colorimetric image quantification (Figure 1C) showed a high level of uptake of all nanoparticle types.

Figure 1.

Role of the complement in the uptake of different iron oxide nanoparticles: (A) TEM images of particles prepared for the study. Size bar, 50 nm. (B) Uptake by peritoneal macrophages (Prussian blue) in wild type or C3 knockout sera. (C) Prussian blue quantification shows inhibition of uptake of small and large SPIO NWs, but not of Feraheme, in C3 KO serum. Repeated four times. (D) Measurement of mouse C3 per nanoparticle (in arbitrary units) shows much less deposition on Feraheme and ultrasmall SPIO than on SPIO NWs. EDTA (10 mM) is the inhibitor of all complement pathways. Two-sided t test. N = 3, repeated three times. (E) Smaller nanoparticles accommodate fewer C3b molecules and theoretically cannot accommodate the bulky complement convertase (C3Bb-properdin). Nanoparticle–protein real size models of C3b and C3 convertase were described before.23 Size bar, 50 μm for all images.

While the uptake of S-SPIO NWs and L-SPIO NWs was almost completely (>90%) inhibited, there was no decrease in the uptake of Feraheme in C3 deficient serum. Previously, we demonstrated that S-SPIO NWs and L-SPIO NWs potently activate the complement in human sera29,30 and that Feraheme bound fewer C3 molecules per nanoparticle. We measured C3 deposition per nanoparticle in mouse serum (in arbitrary units, due to lack of purified mouse C3 as a standard) and found that it decreases with nanoparticle size and is much less for Feraheme and USPIO than for S-SPIO NWs and L-SPIO NWs (Figure 1D). The size of particles after incubation in serum was either unchanged or increased, but USPIO and Feraheme were still smaller than S-SPIO NWs and L-SPIO NWs (Supplemental Figure S1). One possible explanation of the differences in C3 opsonization could be the size limitations with smaller particles being unable to accommodate C3 molecules (~15 nm) and the convertase (C3Bb/Properdin) (Figure 1E), but this needs to be investigated further.

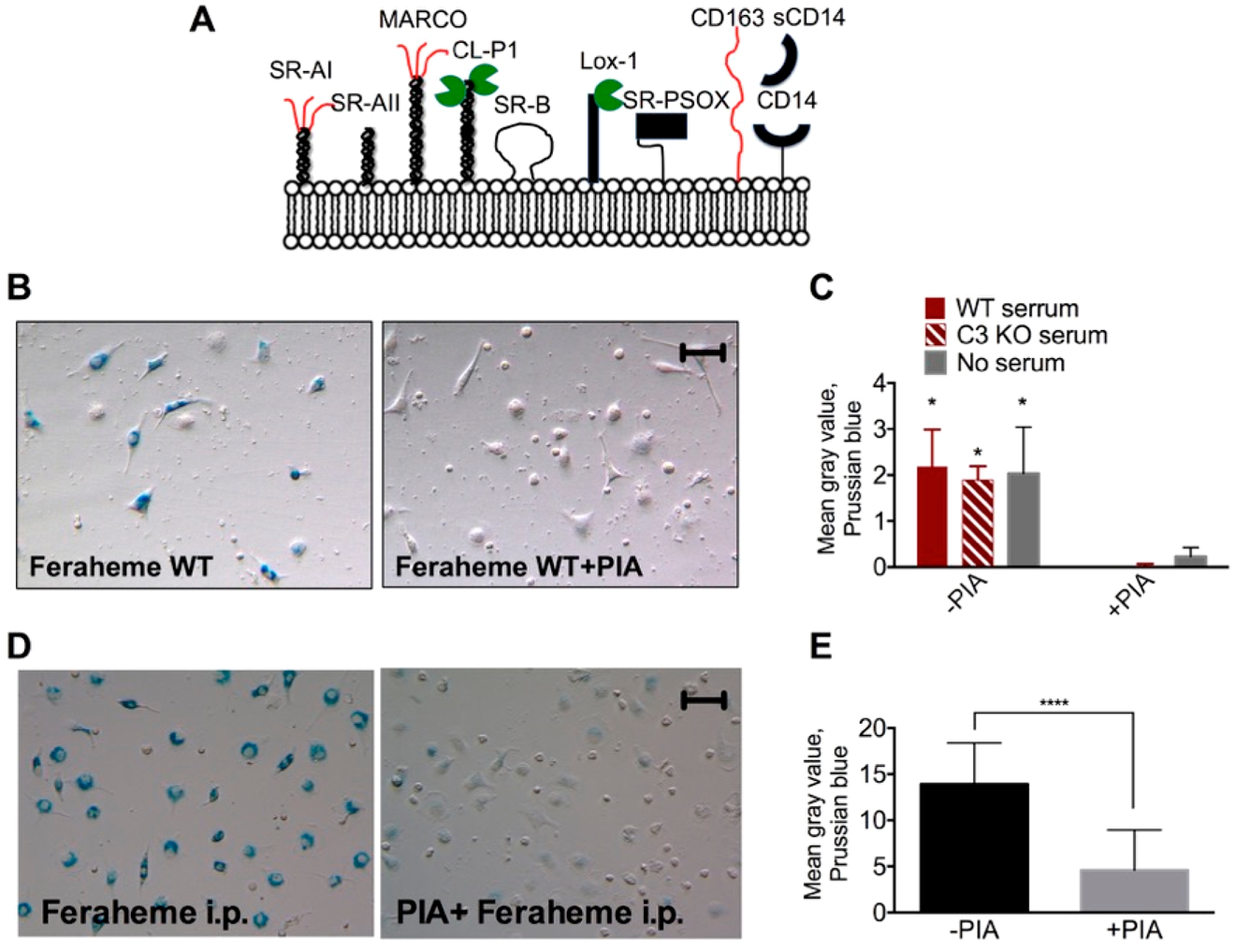

Scavenger receptors (SRs) are the diverse group of phagocytic receptors (Figure 2A) that mediate recognition patterns presented on the surface of lipoproteins, apoptotic bodies, and pathogens.31 SR type A (SR-A) is the predominant type of SRs expressed on macrophages. This group includes SR-AI/II and MARCO (macrophage receptor with collagen). SR-AI consists of collagen-like domain and cysteine-rich domains, whereas SR-AII is a splicing variant that lacks a cysteine-rich domain (Figure 2A, ref 32). For both SR-AI and SR-AII, collagen-like domain is responsible for recognition of polyanions, including nanoparticles.26,33,34 In the case of MARCO, the cysteine-rich domain, rather than the collagen-like domain, mediates the recognition of ligands, but with different specificity than SR-AI/II.33,35,36 SR-A mediated endocytosis can be effectively inhibited by polyanions, including polyinosinic acid, fucoidan, and dextran sulfate.31,34

Figure 2.

Uptake of Feraheme by peritoneal macrophages is mediated by scavenger receptors in vitro and in vivo. (A) Scavenger receptors are a large group of phagocytic receptors recognizing molecular patterns, mostly negatively charged. (B–C) Prussian blue staining and image quantification show blockage of in vitro Feraheme uptake by polyinosinic acid (PIA), a well established SR inhibitor. Repeated three times. (D,E) Blockade of in vivo Feraheme uptake by PIA following intrapertioneal injection. Two-sided t test. N = 3, repeated three times. Size bar, 50 μm for all images.

We tested the uptake of Feraheme by PM in normal serum, C3 deficient serum, and serum-free medium in the presence or absence of 20 μg/mL polyinosinic acid (PIA). According to PB staining and PB image quantification (Figure 2B–C), PIA completely inhibited the uptake of Feraheme in serum-free medium, in WT serum, and in C3 deficient serum, suggesting involvement of the SRs and no involvement of complement. The effect of PIA measured with PB was consistent with the intracellular iron measured with ICP–MS (Supplemental Figure S2). To test the ability of PIA to inhibit PM uptake in vivo, we injected BALB/c mice i.p. with PBS or PIA, then i.p. with Feraheme, collected PMs 6 h later, and stained them with Prussian blue. According to Figure 2D,E, control mice showed strong uptake, whereas PIA-treated mice showed about 80% less uptake.

We further probed the identity of the receptor using blocking antibodies against key SRs SR-AI/II, CD14, MARCO, SR-BI as well as against CD11b (complement receptor CR3). Preincubation of PMs with anti-SR-AI/II significantly inhibited (by 86%) the uptake of Feraheme, whereas other antibodies did not exert any inhibitory effect (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

SR-AI/II recognizes Feraheme in vitro. (A,B) Prussian blue and image quantification show that SR-AI/II antibody almost completely abolished the uptake by peritoneal macrophages. Other blocking antibodies did not have any effect on the uptake. N = 3, repeated two times. (C) Immunostaining of PM with anti-SR-AI/II antibody. (D) Uptake of Feraheme by CHO cells transfected with SR-AI plasmid. Repeated three times. Size bar, 50 μm for all images.

The phagocytic function of macrophage receptors can be reconstituted by expressing them in nonphagocytic cells via transfection or viral transduction.26 In order to confirm the ability to mediate the uptake of Feraheme, we transfected CHO cells with plasmid coding for SR-AI as described by us before26 (Figure 3C). The transfected cells were incubated with 0.1 mg Fe/mL of Feraheme or control USPIO coated with neutral 10 kDa dextran (as opposed to 10 kDa carboxymethyl dextran in Feraheme). According to PB staining (Figure 3D) and ICP–MS quantification (Supplemental Figure S2), Feraheme was efficiently internalized by SR-AI-transfected cells, and the uptake was inhibited by PIA. There was almost no uptake of USPIO by SR-AI transfected cells and no uptake of Feraheme by GFP-transfected cells (Figure 3D and ICP–MS data in Supplemental Figure S2). These data confirm the role of SR-AI and suggest that the anionic charge of Feraheme plays an important role in recognition via SR-AI.

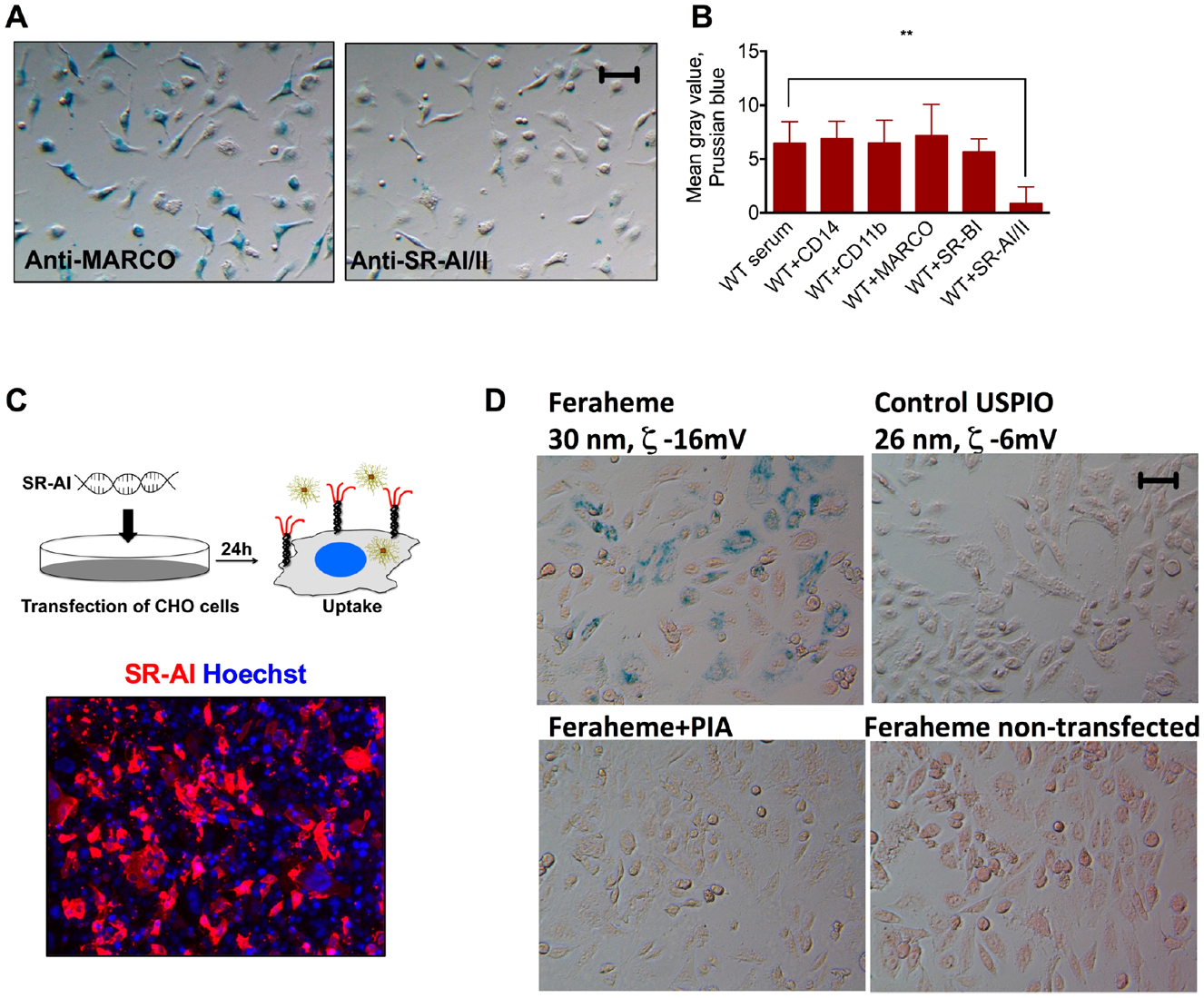

SR-AI/II Mediates Uptake of Feraheme by Pro- and Anti-inflammatory Bone Marrow Derived Macrophages (BMDMs).

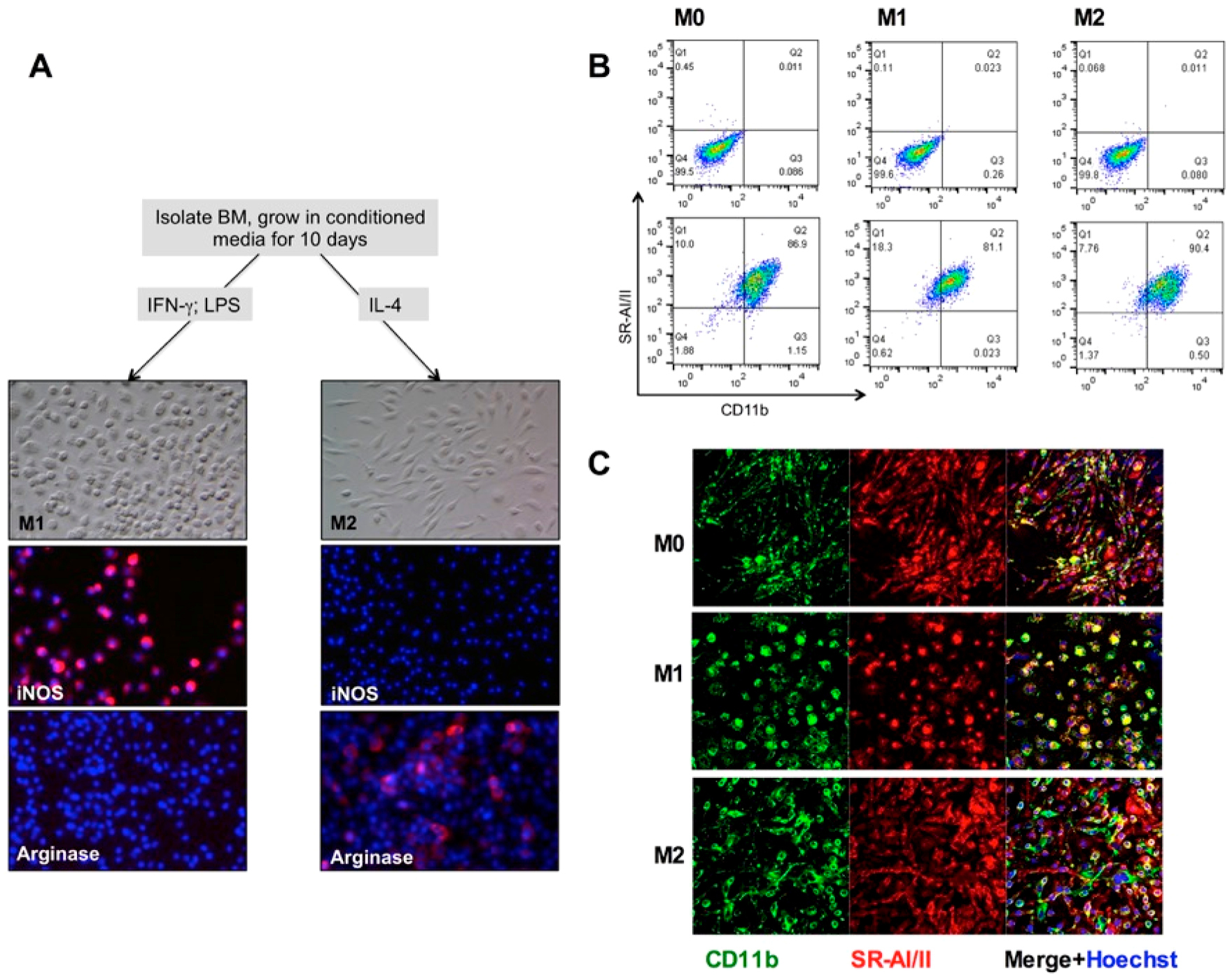

We next tested the role of SRs in the uptake of Feraheme by BMDMs. Bone marrow cells were isolated from BALB/c mice, induced into BMDMs in fibroblast conditioned media, and then differentiated into M1 and M2 types using the established protocol (Figure 4A and ref 37, details in Materials and Methods). M1-like macrophages had mostly the round shape and expressed iNOS, whereas M2-like macrophages had mostly the elongated shape and expressed arginase (Figure 4A). Nondifferentiated macrophages (M0) had a mixed morphology. The difference in the shape of these types of macrophages has been described before.38 Flow cytometry analysis (Figure 4B) and immunofluorescence staining (Figure 4C) showed that over 90% of BMDMs expressed SR-AI/II, with expression levels similar between M0, M1, and M2 types.

Figure 4.

Expression of SR-AI/II by bone marrow derived macrophages. (A) BMDM differentiation scheme. M1 macrophages are rounded, expressing iNOS and not Arg1, whereas M2 macrophages are elongated, expressing Arg1 and not iNOS. (B) Flow cytometry of BMDM stained for CD11b and SR-AI/II. Upper row, nonstained cells. (C) Confocal microscopy of BMDM stained for CD11b and SR-AI/II.

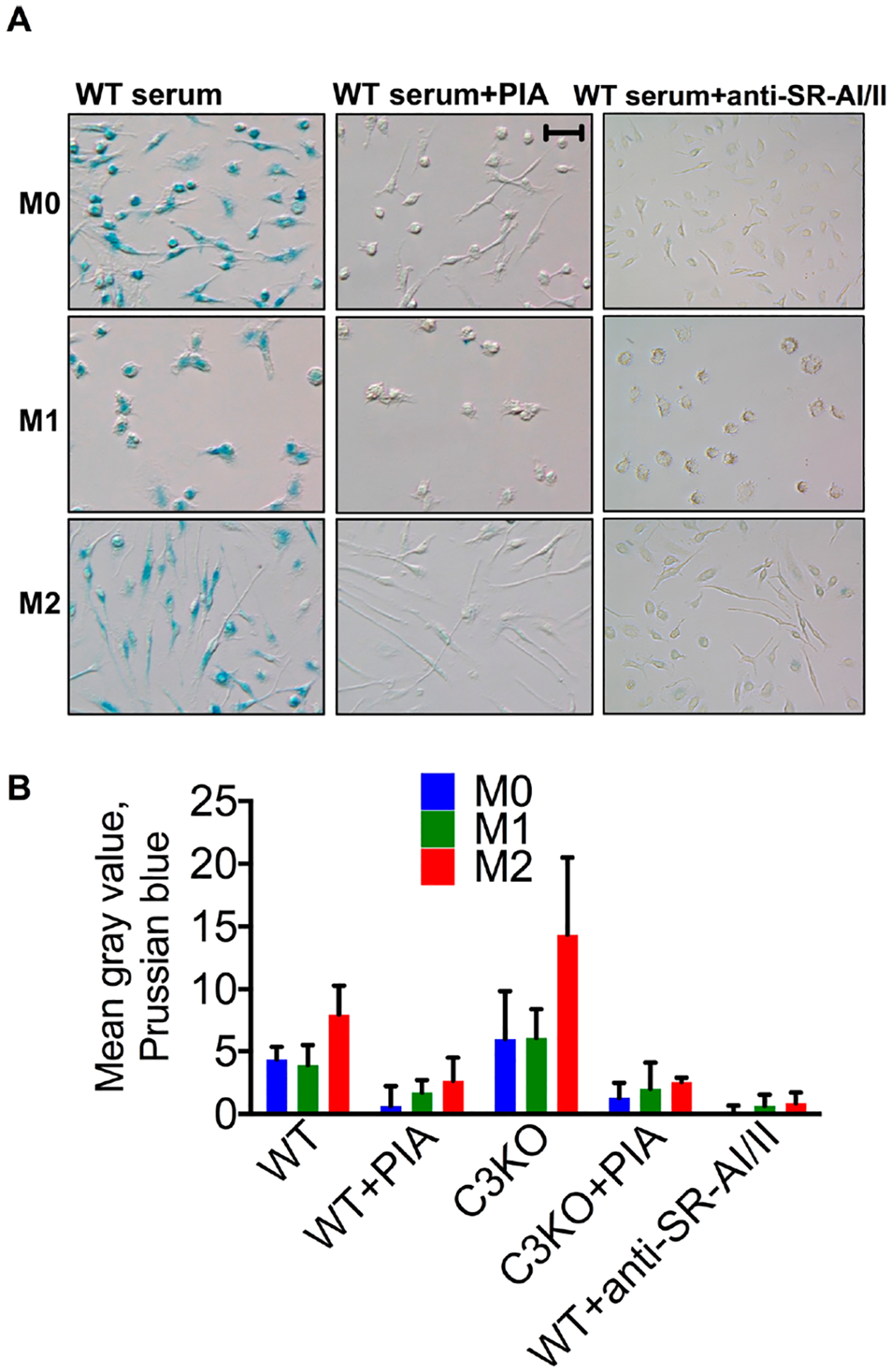

Cells were incubated with 0.1 mg Fe/mL Feraheme in the presence of WT or C3 deficient serum and in the presence or absence of 20 μg PIA/mL. Prussian blue stained images (Figure 5A) and quantification (Figure 5B and ICP–MS data in Supplemental Figure 2) showed that all BMDM types efficiently internalized Feraheme in both WT and C3 deficient sera. In some experiments, M2 type showed higher uptake than the other types, despite similar expression of SR-AI/II, but no clear trend was observed. At the same time, the uptake of Feraheme by all BMDM types and in all sera was inhibited by PIA (Figure 5A,B and ICP–MS data in Supplemental Figure 2). Furthermore, anti-SR-AI/II antibody inhibited the uptake by all macrophage types (Figure 5A,B and ICP–MS data in Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 5.

SR-AI/II mediates uptake of Feraheme by BMDM. (A) Representative Prussian blue images and (B) image quantification shows inhibition by PIA and anti-SR-AI/II antibody, regardless of the serum type. WT vs SR-AI/II Ab: p-value 0.012 for M0, M1, M2; two-tailed t test, n = 5, repeated three times. Size bar 50 μm for all images.

DISCUSSION

We determined the receptor mediating the uptake of Feraheme by peritoneal macrophages in vitro and in vivo and by pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophages in vitro. SR-AI/II was the predominant uptake mechanism for Feraheme, based on the robust inhibition of Feraheme uptake by PIA and anti-SR-AI/II antibody and the enhanced uptake by nonphagocytic cells that overexpress SR-AI. In view of the clear effect of SR-AI/II inhibition, we did not investigate all the SRs mentioned in Figure 2A. We also found no evidence of involvement of complement in the uptake of Feraheme in vitro. This is in striking contrast to SPIO NWs, which are larger nanoparticles coated with neutral 20 kDa dextran. Previously, we reported that Feraheme does not accommodate more than 1–2 human C3 molecules per nanoparticle, as compared to larger SPIO NWs that accommodate tens of C3 molecules.30 Here, we found that the level of C3 deposition per nanoparticle correlates with the uptake. It is possible that there is a minimum number of C3b molecules required for engagement of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) receptor, but this hypothesis needs to be tested further.

Our studies established the role of SR-AI/II in the uptake by peritoneal macrophages and bone marrow derived macrophages. We did not investigate the effect of SR-AI/II on the clearance by different macrophage populations after systemic injection. Previous studies showed that SR-AI/II knockouts only partially prevented clearance of pathogens, damaged cells, and particles.39–41 This result was also similar to our previous study where the liver uptake of Feridex was not inhibited by PIA.42 However, a recent study demonstrated the efficient prolongation (four-fold) of negatively charged iron oxide nanoparticles’ circulation by fucoidan, a potent inhibitor of SRs.43 The nanoparticles used in that study were larger than Feraheme, but coated with a similar carboxymethyl dextran. It would be interesting to see if the simultaneous blockade of complement and SR-AI/II could further extend the circulation of those nanoparticles.

With the emerging role of TAMs in tumor progression and response to therapies,44,45 development of imaging agents for macrophage phenotyping and profiling can improve diagnostics and monitoring of cancer disease.15 While the identification of mechanisms responsible for SPIO clearance and uptake by disease-associated macrophages in vivo is a long undertaking, it is an important venue of research in nanomedicine and should be pursued further. Based on our studies, the next set of questions would be to elucidate the role of SR-AI/II in the uptake of Feraheme by macrophages in the disease models, in particular by TAMs in cancer models. It was shown that SR-AI/II expression correlates with tumor progression and aggressiveness.46,47 Since SR-AI/II is equally expressed on both M1 and M2 macrophage types, our data bring up questions regarding the use of Feraheme-enhanced MRI for specific detection of subpopulations of TAMs. While Feraheme is currently the only clinically approved nanoparticle that is used off-label for T2 contrast MRI, it makes sense for the imaging community to further investigate Feraheme’s selectivity and invest effort in development of more specific agents. The effect of size and charge on the pathways of uptake can be exploited for the design of such agents.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the NIH grants EB022040 and CA194058 to D.S.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMDM

bone marrow derived macrophages

- PIA

polyinosinic acid

- PM

peritoneal macrophage

- TAM

tumor associated macrophages

- SPIO NW

superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoworm

- USPIO

ultrasmall SPIO

- SR

scavenger receptors

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00632.

Supplemental methods on size in serum and ICP–MS; Figure S1, size distribution in serum; Figure S2, ICP–MS measurements (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Wynn TA; Chawla A; Pollard JW Macrophage Biology in Development, Homeostasis and Disease. Nature 2013, 496, 445–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Mantovani A; Sica A; Sozzani S; Allavena P; Vecchi A; Locati M The Chemokine System in Diverse Forms of Macrophage Activation and Polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004, 25, 677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Martinez FO; Gordon S The M1 and M2 Paradigm of Macrophage Activation: Time for Reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014, 6, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Weissleder R; Nahrendorf M; Pittet MJ Imaging Macrophages with Nanoparticles. Nat. Mater 2014, 13, 125–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lehmann B; Biburger M; Bruckner C; Ipsen-Escobedo A; Gordan S; Lehmann C; Voehringer D; Winkler T; Schaft N; Dudziak D; Sirbu H; Weber GF; Nimmerjahn F Tumor Location Determines Tissue-Specific Recruitment of Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Antibody-Dependent Immunotherapy Response. Sci. Immunol 2017, 2, eaah6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Genard G; Lucas S; Michiels C Reprogramming of Tumor-Associated Macrophages with Anticancer Therapies: Radiotherapy Versus Chemo- and Immunotherapies. Front. Immunol 2017, 8, 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gupta AK; Gupta M Synthesis and Surface Engineering of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3995–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nahrendorf M; Keliher E; Marinelli B; Waterman P; Feruglio PF; Fexon L; Pivovarov M; Swirski FK; Pittet MJ; Vinegoni C; Weissleder R Hybrid Pet-Optical Imaging Using Targeted Probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 7910–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gazeau F; Levy M; Wilhelm C Optimizing Magnetic Nanoparticle Design for Nanothermotherapy. Nanomedicine (London, U. K.) 2008, 3, 831–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Figuerola A; Di Corato R; Manna L; Pellegrino T From Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Towards Advanced Iron-Based Inorganic Materials Designed for Biomedical Applications. Pharmacol. Res 2010, 62, 126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Raynal I; Prigent P; Peyramaure S; Najid A; Rebuzzi C; Corot C Macrophage Endocytosis of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Mechanisms and Comparison of Ferumoxides and Ferumoxtran-10. Invest. Radiol 2004, 39, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Simberg D; Park JH; Karmali PP; Zhang WM; Merkulov S; McCrae K; Bhatia SN; Sailor M; Ruoslahti E Differential Proteomics Analysis of the Surface Heterogeneity of Dextran Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and the Implications for Their in Vivo Clearance. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3926–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bulte JW; Kraitchman DL Iron Oxide Mr Contrast Agents for Molecular and Cellular Imaging. NMR Biomed. 2004, 17, 484–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Moore A; Weissleder R; Bogdanov A Jr. Uptake of Dextran-Coated Monocrystalline Iron Oxides in Tumor Cells and Macrophages. J. Magn Reson Imaging 1997, 7, 1140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yang R; Sarkar S; Yong VW; Dunn JF In Vivo Mr Imaging of Tumor-Associated Macrophages: The Next Frontier in Cancer Imaging. Magn Reson Insights 2018, 11, 1178623X18771974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Toth GB; Varallyay CG; Horvath A; Bashir MR; Choyke PL; Daldrup-Link HE; Dosa E; Finn JP; Gahramanov S; Harisinghani M; Macdougall I; Neuwelt A; Vasanawala SS; Ambady P; Barajas R; Cetas JS; Ciporen J; DeLoughery TJ; Doolittle ND; Fu R; et al. Current and Potential Imaging Applications of Ferumoxytol for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 47–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kirschbaum K; Sonner JK; Zeller MW; Deumelandt K; Bode J; Sharma R; Kruwel T; Fischer M; Hoffmann A; da Silva MC; Muckenthaler MU; Wick W; Tews B; Chen JW; Heiland S; Bendszus M; Platten M; Breckwoldt MO In Vivo Nanoparticle Imaging of Innate Immune Cells Can. Serve as a Marker of Disease Severity in a Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 13227–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ramanathan RK; Korn RL; Raghunand N; Sachdev JC; Newbold RG; Jameson G; Fetterly GJ; Prey J; Klinz SG; Kim J; Cain J; Hendriks BS; Drummond DC; Bayever E; Fitzgerald JB Correlation between Ferumoxytol Uptake in Tumor Lesions by Mri and Response to Nanoliposomal Irinotecan in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: A Pilot Study. Clin. Cancer Res 2017, 23, 3638–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Harisinghani M; Ross RW; Guimaraes AR; Weissleder R Utility of a New Bolus-Injectable Nanoparticle for Clinical Cancer Staging. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 1160–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yuan HS; Wilks MQ; Normandin MD; El Fakhri G; Kaittanis C; Josephson L Heat-Induced Radiolabeling and Fluorescence Labeling of Feraheme Nanoparticles for Pet/Spect Imaging and Flow Cytometry. Nat. Protoc 2018, 13, 392–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kaittanis C; Shaffer TM; Ogirala A; Santra S; Perez JM; Chiosis G; Li YM; Josephson L; Grimm J Environment-Responsive Nanophores for Therapy and Treatment Monitoring Via Molecular Mri Quenching. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zanganeh S; Hutter G; Spitler R; Lenkov O; Mahmoudi M; Shaw A; Pajarinen JS; Nejadnik H; Goodman S; Moseley M; Coussens LM; Daldrup-Link HE Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Inhibit Tumour Growth by Inducing Pro-Inflammatory Macrophage Polarization in Tumour Tissues. Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Chen F; Wang G; Griffin JI; Brenneman B; Banda NK; Holers VM; Backos DS; Wu L; Moghimi SM; Simberg D Complement Proteins Bind to Nanoparticle Protein Corona and Undergo Dynamic Exchange in Vivo. Nat. Nanotechnol 2017, 12, 387–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Inturi S; Wang G; Chen F; Banda NK; Holers VM; Wu L; Moghimi SM; Simberg D Modulatory Role of Surface Coating of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoworms in Complement Opsonization and Leukocyte Uptake. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10758–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Banda NK; Mehta G; Chao Y; Wang G; Inturi S; Fossati-Jimack L; Botto M; Wu L; Moghimi S; Simberg D Mechanisms of Complement Activation by Dextran-Coated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide (Spio) Nanoworms in Mouse Versus Human Serum. Part. Fibre Toxicol 2014, 11, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chao Y; Makale M; Karmali PP; Sharikov Y; Tsigelny I; Merkulov S; Kesari S; Wrasidlo W; Ruoslahti E; Simberg D Recognition of Dextran-Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Conjugates (Feridex) Via Macrophage Scavenger Receptor Charged Domains. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23, 1003–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wang G; Chen F; Banda NK; Holers VM; Wu L; Moghimi SM; Simberg D Activation of Human Complement System by Dextran-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Is Not Affected by Dextran/Fe Ratio, Hydroxyl Modifications, and Crosslinking. Front. Immunol 2016, 7, 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Vu VP; Gifford GB; Chen F; Benasutti H; Wang G; Groman EV; Scheinman R; Saba L; Moghimi SM; Simberg D Immunoglobulin Deposition on Biomolecule Corona Determines Complement Opsonization Efficiency of Preclinical and Clinical Nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol 2019, 14, 260–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wang G; Griffin JI; Inturi S; Brenneman B; Banda NK; Holers VM; Moghimi SM; Simberg D In Vitro and in Vivo Differences in Murine Third Complement Component (C3) Opsonization and Macrophage/Leukocyte Responses to Antibody-Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoworms. Front. Immunol 2017, 8, 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Benasutti H; Wang G; Vu VP; Scheinman R; Groman E; Saba L; Simberg D Variability of Complement Response toward Preclinical and Clinical Nanocarriers in the General Population. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 2747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Platt N; Gordon S Scavenger Receptors: Diverse Activities and Promiscuous Binding of Polyanionic Ligands. Chem. Biol 1998, 5, R193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Taylor PR; Martinez-Pomares L; Stacey M; Lin HH; Brown GD; Gordon S Macrophage Receptors and Immune Recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol 2005, 23, 901–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jozefowski S; Arredouani M; Sulahian T; Kobzik L Disparate Regulation and Function of the Class a Scavenger Receptors Sr-Ai/Ii and Marco. J. Immunol 2005, 175, 8032–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Doi T; Higashino K; Kurihara Y; Wada Y; Miyazaki T; Nakamura H; Uesugi S; Imanishi T; Kawabe Y; Itakura H; et al. Charged Collagen Structure Mediates the Recognition of Negatively Charged Macromolecules by Macrophage Scavenger Receptors. J. Biol. Chem 1993, 268, 2126–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Arredouani MS; Kobzik L The Structure and Function of Marco, a Macrophage Class a Scavenger Receptor. Cellular & Molecular Biology (Noisy-Le-Grand, France) 2004, 50, OL657–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ojala JR; Pikkarainen T; Tuuttila A; Sandalova T; Tryggvason K Crystal Structure of the Cysteine-Rich Domain of Scavenger Receptor Marco Reveals the Presence of a Basic and an Acidic Cluster That Both Contribute to Ligand Recognition. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 16654–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jablonski KA; Amici SA; Webb LM; Ruiz-Rosado Jde D; Popovich PG; Partida-Sanchez S; Guerau-de-Arellano M Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2Macrophages. PLoS One 2015, 10, No. e0145342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rodell CB; Arlauckas SP; Cuccarese MF; Garris CS; Li R; Ahmed MS; Kohler RH; Pittet MJ; Weissleder R Tlr7/8-Agonist-Loaded Nanoparticles Promote the Polarization of Tumour-Associated Macrophages to Enhance Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Biomed Eng 2018, 2, 578–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Zhou H; Imrich A; Kobzik L Characterization of Immortalized Marco and Sr-Ai/Ii-Deficient Murine Alveolar Macrophage Cell Lines. Part. Fibre Toxicol 2008, 5, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Terpstra V; Kondratenko N; Steinberg D Macrophages Lacking Scavenger Receptor a Show a Decrease in Binding and Uptake of Acetylated Low-Density Lipoprotein and of Apoptotic Thymocytes, but Not of Oxidatively Damaged Red Blood Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997, 94, 8127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Adachi H; Tsujimoto M; Arai H; Inoue K Expression Cloning of a Novel Scavenger Receptor from Human Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 31217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wang G; Groman E; Simberg D Discrepancies in the in Vitro and in Vivo Role of Scavenger Receptors in Clearance of Nanoparticles by Kupffer Cells. Precision Nanomedicine 2018, 1, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Abdollah MRA; Carter TJ; Jones C; Kalber TL; Rajkumar V; Tolner B; Gruettner C; Zaw-Thin M; Baguna Torres J; Ellis M; Robson M; Pedley RB; Mulholland P; d. R. R TM; Chester KA Fucoidan Prolongs the Circulation Time of Dextran-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1156–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jeong H; Hwang I; Kang SH; Shin HC; Kwon SY Tumor-Associated Macrophages as Potential Prognostic Biomarkers of Invasive Breast Cancer. Journal of Breast Cancer 2019, 22, 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Wu SQ; Xu R; Li XF; Zhao XK; Qian BZ Prognostic Roles of Tumor Associated Macrophages in Bladder Cancer: A System Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 25294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Neyen C; Pluddemann A; Mukhopadhyay S; Maniati E; Bossard M; Gordon S; Hagemann T Macrophage Scavenger Receptor a Promotes Tumor Progression in Murine Models of Ovarian and Pancreatic Cancer. J. Immunol 2013, 190, 3798–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Miyasato Y; Shiota T; Ohnishi K; Pan C; Yano H; Horlad H; Yamamoto Y; Yamamoto-Ibusuki M; Iwase H; Takeya M; Komohara Y High Density of Cd204-Positive Macrophages Predicts Worse Clinical Prognosis in Patients with Breast Cancer. Cancer Science 2017, 108, 1693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.