Abstract

Introduction

Communication is an essential aspect of care for patients with progressive serious illnesses. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of a new, integrated communication support program for oncologists, patients with rapidly progressing advanced cancer and their caregivers.

Methods and analysis

The proposed integrated communication support programme is in the randomised control trial stage. It comprises a cluster of oncologists from comprehensive cancer centre hospitals in a metropolitan area in Japan. A total of 20 oncologists, 200 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and the patients’ caregivers are enrolled in this study as of the writing of this protocol report. Oncologists are randomly assigned to the intervention group (IG) or control group (CG). Patients and caregivers are allocated to the same group as their oncologists. The IG oncologists receive a 2.5-hour individual communication skills training, and patients and caregivers receive a half-hour coaching intervention to facilitate prioritising and discussing questions and concerns; the CG participants do not receive any training. Follow-up data will be collected quarterly for 6 months for a year and then annually for up to 3 years. The primary endpoint is the intergroup difference between before-intervention and after-intervention patient-centred communication behaviours during oncology visits.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for clinical studies published by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Cultural, Sports, Science and Technology, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the ethical principles established for research on humans stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and further amendments thereto. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cancer Center, Japan on 4 July 2018 (ID: 2017-474).

Trial status

This study is currently enrolling participants. Enrolment period ends 31 July 2020; estimated follow-up date is 31 March 2023.

Trial registration number

UMIN Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000033612); pre-results.

Keywords: adult oncology, adult palliative care, mental health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is the use of a large group of patients, caregivers and oncologists in the real-world scenario for which the intervention is being tested.

The use of multicenter participant samples, controls and patient follow-up allows for reliable study results.

This study includes oncologists, patients and caregivers for intervention.

The intervention programme is complex, consisting of multiple factorial components, which makes it difficult to determine which interventions and components are most efficacious or beneficial; however, participants provide subjective assessments of the intervention components.

The study only involves pancreatic cancer, so the generalisation potential for other cancers is unknown. However, as pancreatic cancer is one of the most rapidly progressing cancers, if the intervention is effective for patients with pancreatic cancer who have severe physical and psychological conditions, it may be applied to patients with other cancers as well.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of death in Japan, with approximately 35 000 new cases diagnosed per year, matching the approximate annual number of deaths from the disease nationally.1 Over 40% of patients with pancreatic cancer are stage IV at diagnosis, and the 3-year survival rate for stages III and IV is 11.9% and 2.5%, respectively.2 Although the initial treatment goal for pancreatic cancer is to cure, even prolonged survival and maintenance of quality of life (QoL) are difficult to achieve.

Most patients with advanced cancer prefer to discuss their prognosis and treatments with their physicians.3 However, physicians may feel burdened by open discussions for fear of patients losing hope, or they may face resistance from caregivers4; therefore, these discussions rarely occur.5 Consequently, patients often overestimate the hopefulness of prognoses, underestimate disease severity and have unrealistic expectations for a cure.6 Patients who have not discussed prognosis and treatment choices with their oncologists are three to eight times more likely to receive aggressive treatments in their last week of life.5 7 Although oncologists and patients find that prognostic discussions can be stressful, unnecessary expenses and actual harm to the patient may result from uninformed decisions.8 Additionally, it has been shown that open discussions do not cause hopelessness or increased fear in patients and that well-informed patients make more appropriate treatment choices.9 10 Hence, oncologists need to provide adequate information regarding cancer treatment decisions for patients and their caregivers approaching the end of life, confirm patients’ and caregivers’ understanding, and achieve shared decision-making about treatment and care based on patients’ personal values, life goals and treatment preferences.

In previous study, patients from the diagnosis to the discontinuation of anticancer drug treatment stage (mainly patients with pancreatic cancer) showed to desire more ‘empathic communication’ from oncologists.11 Empathic communication by oncologists reduces patients’ psychological distress,12 increases trust in the oncologist12 and enhances information recall.13 Empathic communication is essential especially for patients with rapidly progressing serious illnesses. Therefore, communication skills training (CST) programmes have been developed to help physicians to facilitate communication behaviours that strengthen relationships with patients.14 CST involves learner-centred workshop held in small groups and includes role-play with simulated patients (SPs).15 It is strongly recommended that medical professionals train themselves in communication skills based on American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guidelines for patient–clinician communication.16 Learning tools (eg, www.vitaltalk.org) are available to medical practitioners to support this learning.

We conducted a prior survey clarifying the four elements of communication skills patients prefer oncologists to have, referred to as SHARE: ‘setting,’ ‘how to deliver the bad news,’ ‘additional information,’ and ‘reassurance and emotional support.’17 18 A 2-day SHARE-CST programme for oncologists was developed based on these preferences.19 The programme is a small-group workshop including the above-mentioned modules; it employs role-play with SPs and immediate feedback15 to allow learners to practice discussing serious news with patients with cancer and caregivers, such as transition to palliative care when chemotherapy is failing. The programme emphasises that physicians respect the values of each patient and provide reassurance and emotional support, and has been implemented in several Asian countries.20 Our previous randomised controlled trial (RCT) of physicians, including oncologists treating pancreatic cancer, showed that oncologists who participated in SHARE-CST improved their behaviour in terms of patient-preferred communication as well as their self-confidence in communication with patients and that their patients experienced a relatively low level of psychological distress and a high level of trust in the oncologist.12 In Japan, SHARE-CST was implemented as a 10-year project commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for physicians nationwide after the enactment of the National Cancer Control Act. Participants reported that their empathic communication attitudes and abilities had improved21; however, it was difficult for most oncologists to participate in 2-day CST group workshops because of the busy clinical oncology settings in which they worked.

Patient-centred approaches using question prompt lists (QPLs) have also been proposed for the improvement of patient–physician communication. A QPL is an inexpensive communication tool employing a structured question list to encourage patient question-asking and participation during consultations.22 The provision of a QPL and implementation of communication interventions with QPL before consultation is effective in promoting patient question-asking behaviour and participation in the consultation and in decreasing patients’ anxiety.23 Our previous RCT of patients with advanced gastric, colorectal, oesophageal and lung cancer showed that QPL was useful in making initial treatment decisions for them but failed to promote patient question-asking behaviour,24 in part because Japanese patients tend to wait for physicians to encourage them to ask questions.25 The number of patients asking their physician questions was median 1, compared with mean/median 8.5 –14 in studies in Western countries.23 24 In Japan, it has been reported that patients with cancer have preference of not being burden to others and of ‘omakase’ (leaving the decision-making to a medical expert), and it is difficult to elicit the patient’s preference.26 Thus, in Japan, integrated interventions combining CST for oncologists and communication coaching with QPL for patients might increase patient questioning behaviour and improve patient-centred communication in consultations.27 28

Based on the results of previous trials, this study aims to evaluate the efficacy of a new, integrated communication support programme, consisting of a CST for oncologists and communication coaching with QPL for patients with rapidly progressing advanced cancer and their caregivers, promoting oncologists’ patient-centred communication behaviours. We hypothesise that, compared with treatment as usual (TAU), the intervention will increase oncologists’ patient-centred communication behaviours, increase patients’ question-asking behaviours, and improve patients’ well-being and health services utilisation by reducing aggressive interventions and increasing use of palliative care.

Methods and analysis

This protocol was written in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) and SPIRIT PRO Extension Guidelines.29 30

Study design

This study is a single-blind cluster RCT conducted in four metropolitan cancer-treatment hospitals: the National Cancer Center Hospital, the National Cancer Center Hospital East, the Cancer Institute Hospital and the Kanagawa Cancer Center Hospital. This study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the protocol review committee of the Japan Supportive, Palliative and Psychosocial Oncology Group as J-SUPPORT 1704 and by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution.

An independent data centre provides computer-generated random allocation sequences. The assignment sequence is centrally managed; assignment results are automatically sent to a clinical research coordinator (CRC), electronically. The oncologist participants are randomly assigned to an intervention group (IG) or control group (CG) after the baseline phase; patient/caregiver participants are assigned to the same group as their oncologists. A stratified block-randomisation scheme is used to assure balanced assignment by site. Within each site, oncologists are randomly assigned approximately evenly across IG and CG. Participants in IG provide intervention in addition to TAU, and are unblinded.

Intervention

Oncologists

We modified the original SHARE-CST design,12 adopting a 2.5-hour individual programme with a facilitator and an SP, consisting of lecture with a textbook (30 min) and two role-plays with immediate feedback (see table 1). The original SHARE-CST is a small group consisting of four oncologists, two facilitators and two SPs, and included a lecture and eight role-plays (two times per oncologist) with immediate feedback. The lecture cites evidence of the most important and common patient preferences regarding communication—empathic responses and encouragement to ask questions—and the variability of patients’ preferences in discussing prognoses and being/not being dispassionate; it also demonstrates how to check and elicit patient preferences. Additionally, the lecture explains the QPL and discusses frequently asked questions from patients about information related to treatment and care after standard treatment that relates to patients’ personal values, life goals and preferences, as well as those of their caregivers. During the role-playing and discussion, participants are required to consider a patient’s emotions and concerns caused by bad news, recognition of their disease, social situations and information that they would want to know, and to empathise with the patient. Role-play also includes dealing with patients who bring QPLs.

Table 1.

Components of CST Programme based on SHARE model

| Description | |

| Conceptual communication skills model: SHARE | |

| S | Setting up supportive environment for interview, including fundamental communication skills (eg, greeting patient cordially, looking at patient’s eyes and face) |

| H | Considering how to deliver bad news (eg, not beginning bad news without preamble, checking to see whether talk is fast paced) |

| A | Discussing additional information that patient would like to know (eg, answering patient’s questions fully, explaining second opinion) |

| RE | Providing reassurance and addressing patient’s emotions with empathic responses (eg, remaining silent out of concern for patient’s feelings, accepting patient’s expression of emotions) |

| Component | |

| Lecture | Introduction, communication skills model, evidence on preferences of patients with cancer regarding communication |

| Role-playing | Simulated consultation with simulated patient using communication skills with scenarios, discussing with facilitator, summary |

| Scenarios on communication in advanced care | Discontinuing chemotherapy |

| Dealing with patient asking questions | |

| Setting | 1 participant |

| 1 facilitator | |

| 1 simulated patient | |

| Schedule | Orientation and lecture (30 min) |

| Role-playing with immediate feedback (60 min ×2) | |

CST, communication skills training.

Facilitators provide a lecture, lead the role-play and discuss patients’ potential emotions and communication-related preferences. Facilitators include psychiatrists, psychologists and oncologists, all of whom have had 3 years or more of clinical experience in oncology and participated in specialised 30-hour training workshops facilitating communication skills in oncology. The SPs have also participated in train-the-trainer workshops and 15 hours of SP training.

Patient and caregiver

Communication coaching for patients was developed to facilitate communication with physicians using a 63-question QPL based on in-depth focus-group interviews with 18 participants (5 patients with pancreatic cancer, 3 caregivers for patients with pancreatic cancer, 4 bereaved people who had lost a family with pancreatic cancer and 6 pancreatic oncologists), and previous QPL studies.23 24 31 The QPL is a 10-page A4 sheet containing 63 questions grouped into eight topics (diagnosis and stage of the disease, current and future treatments, management of current/possible future symptoms, daily life activities, care and prognosis post standard treatment, caregivers’ needs, psychological distress and management, and values) and a space for free questions. Patient communication coaching using the QPL is a half-hour programme, conducted individually or with a caregiver, consisting of reading the list to select personally relevant questions, prioritising selected questions, discussing difficulties in asking the questions to their oncologist at their next oncology visit and practising asking their oncologist these questions. The intervention is to be provided to patients individually or with caregivers by clinical psychologists and nurses who have participated in a 10-hour intensive training workshop using an intervention manual. The intervention providers note and summarise the content of all intervention sessions, that is, the information that the patients want to know and their preferences of treatment and care. Before patients’ visits, the oncologist is told which the questions the patients chose to ask from the QPL and the summary of the intervention. Intervention providers hold weekly conferences to review their coaching sessions.

Control condition

CG oncologists are provided neither training nor educational materials. Patients/caregivers in the CG are provided TAU.

Participants

Oncologists

Enrolled oncologists must (1) be mainly engaged in anticancer drug treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer; (2) have provided written informed consent for trial participation.

Patients in baseline phase and intervention and long-term follow-up phase

Enrolled patients must (1) have a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer (adenocarcinoma); (2) have unresectable pancreatic cancer (Union for International Cancer Control stage III or IV) or postoperative recurrence; (3) receive a first-line chemotherapy and be scheduled for a second course; (4) be aged 20 years or older; (5) have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 or 1; (6) regularly visit an enrolled oncologist; (7) provide written informed consent for trial participation; and (8) be able to read, write, understand and speak Japanese.

Patients are excluded if they are (1) judged by their oncologist to have cognitive impairment; (2) unable to complete an electronic Patient Reported Outcome (ePRO) Questionnaire or (3) judged unsuitable for participation by their oncologist.

Caregivers in baseline phase and intervention and long-term follow-up phase

If an enrolled patient is accompanied by a caregiver, the caregiver is also approached. Enrolled caregivers must (1) be aged 20 years or older; (2) regularly accompany an enrolled patient as primary caregiver; (3) provide written informed consent to trial participation; (4) be able to read, write, understand and speak Japanese.

Caregivers are excluded if they are unable to complete an ePRO Questionnaire.

Procedures

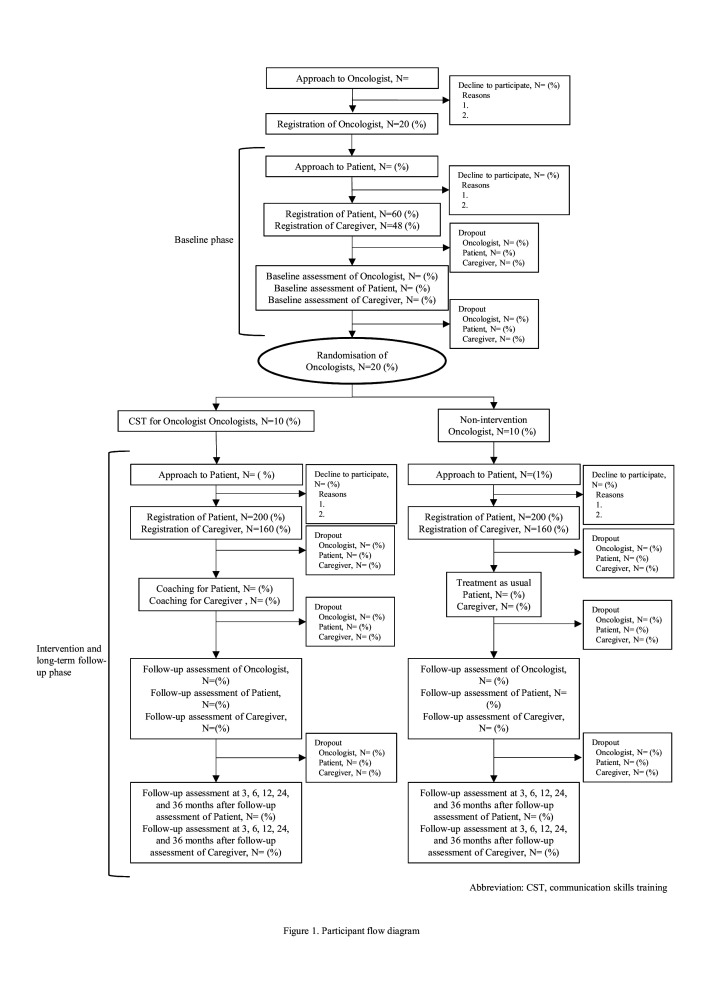

This study consists of three phases: a baseline phase, an intervention phase and a follow-up phase (figure 1). The schedule for outcome measurement is shown in table 2. After completing the intervention phase, data analysis will ensue. After this study has closed, oncologists in the CG will be provided with the intervention on demand.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram. CST, communication skills training.

Table 2.

Schedule for outcome measurement

| Outcome | Measurement | Baseline phase | Intervention phase | Follow-up phase | ||||

| Day 28 of first line chemotherapy | Day 42 of first line chemotherapy | Day 28 of first line chemotherapy | Day 42 of first line chemotherapy | 3, 6, 12, 24, 36 months after | After postmortem of the patient | |||

| Patient in baseline phase | Patient’s communication behaviour | RIAS | 〇 | |||||

| Patient’s medical and sociological background | Cancer stage, diagnosis date, treatment status, treatment history, comorbidities, sex, age, work status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, treatment and care preference at the end of life | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient’s evaluation of consultation | ‘How did the oncologist respond to your questions?’ ‘Did you ask selected questions during consultation?’ ‘How much have you discussed with the oncologist in the visit?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient in intervention and follow-up phase | Patient’s communication behaviour | RIAS | 〇 | |||||

| Patient’s psychological distress | HADS | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s physical and functional QoL | FACT-Physical and Functional | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s comprehensive QoL | Short version of CoQoLo | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s trust in oncologist | TiOS | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s satisfaction with oncologist | CSQ | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s acceptance in cancer experience | PEACE | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s prognosis and treatment perception | PTPQ | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Patient’s evaluation of consultation | ‘How did the oncologist respond to your questions?’ ‘Did you ask selected questions during consultation?’ ‘How much have you discussed with the oncologist in the visit?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient’s evaluation of intervention in the IG | ‘Did you understand how to use the QPL and did you actually use it?’ ‘Do you think you will continue the intervention?’ ‘Was the intervention useful to you?’ ‘Did the oncologist talk about the QPL?’ ‘Did the QPL help you ask the oncologist questions?’ ‘Is the QPL useful?’ ‘Did you read the QPL before the visit?’ ‘Do you think you will read the QPL in the future?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient’s medical and sociological background | Cancer stage, diagnosis date, treatment status, treatment history, comorbidities, sex, age, job status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, treatment and care preference at the end of life | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient’s medical utilisation at the end of life | The date of death, any chemotherapy agent given within 14 days of death, any new chemotherapeutic regimen started within 30 days of death, and involvement of hospice and palliative care services | 〇 | ||||||

| Caregiver in baseline phase | Caregiver’s communication behaviour | RIAS | 〇 | |||||

| Caregiver’s characteristics | Sex, age, relationship with the patient, job status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, and preferences on treatment and care for the patient at the end of life | 〇 | ||||||

| Caregiver’s evaluation of consultation | ‘How did the oncologist respond to your questions?’ ‘Did you ask selected questions during consultation?’ ‘How much have you discussed with your oncologist in the visit?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Caregiver in intervention and follow-up phase | Caregiver’s communication behaviour | RIAS | 〇 | |||||

| Caregiver’s psychological distress | K6 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Caregiver’s QoL | EQ-5D | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | |||

| Caregiver’s satisfaction with oncologist | CSQ | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Caregiver’s sociological background | Sex, age, relationship with the patient, job status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, and preferences on treatment and care for the patient at the end of life | |||||||

| Caregiver’s prognosis and treatment perception | PTPQ | 〇 | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Caregiver’s evaluation of consultation | ‘How did the oncologist respond to your questions?’ ‘Did you ask selected questions during consultation?’ ‘How much have you discussed with the oncologist in the visit?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Caregiver’s evaluation of intervention in the IG | ‘Did you understand how to use the QPL and did you actually use it?’ ‘Do you think you will continue the intervention?’ ‘Was the intervention useful to you?’ ‘Did the oncologist talk about the QPL?’ ‘Did the QPL help you ask the oncologist questions?’ ‘Is the QPL useful?’ ‘Did you read the QPL before the visit?’ ‘Do you think you will read the QPL in the future?’ | 〇 | ||||||

| Patient’s comprehensive end-of-life QoL | Short version of GDI | 〇 | ||||||

| Oncologist | Oncologist’s patient-centred communication behaviours | SHARE-RE | 〇 | 〇 | ||||

| Oncologist’s patient-preferred communication behaviour | SHARE-total | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Oncologist’s patient-preferred communication behaviour | RIAS | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Oncologist’s sociological background | Sex, age, clinical experience | 〇 | ||||||

| Oncologist’s evaluation of medical utilisation by patient | The date of management | 〇 | 〇 | |||||

| Oncologist’s evaluation of intervention | The usefulness of intervention | 〇 | ||||||

CoQoLo, Comprehensive Quality of Life Outcome inventory; CSQ, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; EQ-5D, 5 Dimension EuroQol; FACT-Physical and Functional, Physical Well-being and Functional Well-being subscales of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; GDI, Good Death Inventory; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IG, intervention group; K6, K6 Non-specific Psychological Distress Scale; PEACE, Peace, Equanimity and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience Questionnaire; PTPQ, Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire; QoL, quality of life; QPL, question prompt list; RIAS, Roter Intention Analysis System; SHARE, setting, how to deliver the bad news, additional information, and reassurance and emotional support; TiOS, Trust in Oncologists Scale.

Baseline phase

This phase involves oncologist and patient/caregiver recruitment as well as pre-randomisation data collection on oncologists’ communication behaviours as baseline data for use as a covariate in the RCT analysis. In this phase, three to five patients and their caregivers (if available) will be recruited for each oncologist. Participants will be asked to allow themselves to be audio-recorded at one oncology visit and to provide the evaluation of consultation for primary and secondary outcomes as covariates in the analyses (table 2).

Intervention phase

This phase involves oncologist randomisation, intervention for participants in IG and follow-up assessment. After oncologists are randomly assigned to the IG or CG, those in the IG receive an individual intervention.

Next, 10 patients and their caregivers (if available) who regularly visit the oncologist are recruited and assigned to the IG or CG. After the IG patients and their caregivers receive an intervention, or 2 weeks to 1 month after baseline in the CG, the conversation between the patient/caregiver and the oncologist at their next consultation is audio-recorded. After the consultation, patients/caregivers and the oncologists rate the consultation using a follow-up assessment.

Long-term follow-up phase

Patients and their caregivers will be encouraged to provide long-term follow-up assessments at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 months after the first follow-up assessment to evaluate effects on patient’s physical and psychological condition and medical utilisation at end of life. Caregivers are also asked to provide another assessment at 2–6 months post-patient death.

Data management, central monitoring, data monitoring and auditing

We will collect all data, except for audio-recorded data, through electronic data capture (EDC) and ePRO systems or paper-based PRO questionnaires (pPRO) if patients are prevented from using the electronic approach. If participants fail to respond to ePRO or pPRO, a CRC blinded to the assignment will elicit their answers to avoid missing data. Data management and central monitoring will be performed using EDC VIEDOC 4 (PCG Solutions, Uppsala, Sweden) by the J-SUPPORT Data Science Team. Auditing is not planned for this study.

Concomitant treatments

There is no restriction on concomitant treatments.

Stopping rules for participants

If a participant meets any of the following conditions, the research team can discontinue the intervention; however, the participant will not be considered to have dropped out of the trial at that stage and will still receive the assessments: (1) the participant wishes to stop the intervention; (2) the research team judges that the risk of the intervention is greater than the benefit for any reason; (3) the research team judges that it is difficult to continue the intervention because of clinical deterioration and (4) the research team judges that it is inappropriate to continue the intervention for any reason.

Stopping assessment

If a participant withdraws consent for assessment, he or she will not be followed up. Subjects will be excluded from the intention-to-treat (ITT) cohort of the trial only if they are found to meet any exclusion criteria at baseline after participation.

Assessment measures

Table 2 shows the schedule for outcome measurement.

Primary outcome measure

Oncologist’s patient-centered communication behaviours

The audio-recorded oncology visits for all participants will be coded for each of the four factors of communication behaviours based on patient preference, referred to as SHARE (see table 1).19 The SHARE-RE factor is used as a primary outcome to measure empathic communication between patient/caregiver and oncologist after intervention for both.

Following previous study methods,19 impressions of conversations between patient/caregiver and oncologist from consultations will be assessed using the SHARE-RE factor score, consisting of eight categories for analysis, in a random order, by two blinded coders who have been trained for 30 hours or more on two occasions with a rating manual.

Secondary outcome measure

Oncologist’s patient-preferred communication behaviour

Patient-preferred communication will be analysed using impression ratings from two blinded coders, as described above. The analysis will include the audio-recorded oncology visits for all participants using the total SHARE score, for all 27 categories.18 19 Following previous study methods,19 the 40 categories of the Roter Intention Analysis System (RIAS) will also be used in assessing patient-preferred communications.32

Patient’s and caregiver’s communication behaviour

Following previous study methods,19 the 40 categories of the RIAS will also be used in assessing patient’s and caregiver’s communications behaviour, for example question-asking.32

Patient-reported outcome measures

Several scales will be used to produce a comprehensive profile of each patient participant. These include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale33; the Physical and Functional Well-being subscales of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy34; the short version of the Comprehensive Quality of Life Outcome inventory35; the Trust in Oncologists Scale36; the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ)37; the Peace, Equanimity and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience Questionnaire38; and the Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire.39

Patients’ relevant medical and sociological background information includes stage, diagnosis date, treatment status, treatment history, comorbidities, sex, age, job status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, treatment and care preference at the end of life. Medical utilisation at the end of life will be determined by the date of death, any chemotherapy agent given within 14 days of death, any new chemotherapeutic regimen started within 30 days of death, and involvement of hospice and palliative care services; all of this information is obtained from medical fee information and the caregivers’ assessment at post-patient death.27

A patients’ assessment of the intervention’s usefulness includes ‘Did you understand how to use the QPL and did you actually use it?’, ‘Do you think you will continue the intervention?’ and ‘Was the intervention useful to you?’ Their assessment of oncologists includes ‘Did the oncologist talk about the QPL?’ and ‘How did the oncologist respond to your questions?’ Their assessment of QPL includes ‘Did the QPL help you ask the oncologist questions?’, ‘Is the QPL useful?’, ‘Did you read the QPL before the visit?’ and ‘Do you think you will read the QPL in the future?’ as well as whether they asked selected questions to oncologist after the consultation, which questions they selected, and ‘How much you have discussed with the oncologist in the visit?’ in the intervention phase.

Caregiver survey measures

Several scales will also be used to gain a comprehensive view of caregivers, including the K6 Non-specific Psychological Distress Scale40; the 5 Dimension EuroQol41 and the CSQ.37 After the patient’s death, the caregiver’s QoL as the bereaved is measured with the short version of the Good Death Inventory.42

Caregivers’ relevant sociological background information includes sex, age, relationship with the patient, job status, household income, household size, social support, marital status, educational experience, and treatment and care preferences at end of life.

After the first post-intervention visit, caregivers in the IG will evaluate the intervention, the oncologist and the QPL, and report any selected questions used with the oncologist.

Oncologist survey measures

The relevant data concerning the oncologists include their sociological background (sex, age and clinical experience). The oncologists’ evaluation of medical utilisation by the patient will be set by their recollection of the dates.

The usefulness of intervention will also be measured using evaluations provided by the oncologists in the IG.

Harms

No specific and serious adverse events are presumed for participants in this study. However, by participating in the interventions, some participants may potentially experience psychological distress from imagining their situation after standard treatment. The patients/caregivers and oncologists will also be subjected to time burdens of a half-hour and 2.5 hours for the intervention, and 10–30 min for each baseline and follow-up assessment. Therefore, we will give patients/caregivers a reward of 500 Japanese yen for each participant assessment. There are no reward for the intervention and no financial risks associated with study participation.

Compensation

If participants develop unexpected health issues due to study participation during or after completion of this study, treatment will be adequately provided per standard medical care, covered by the National Health Insurance.

Sample size estimation

Our previous study revealed that the effect size of SHARE-RE score was 1.9 at post-intervention.12 For a sample size based on 80% power to detect a significant difference at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided), 10 oncologists and 70–100 participants (7–10 per oncologist) would be required for each arm in the follow-up phase, assuming some participants drop out and data loss. Assuming that 80% of patients will be accompanied by caregivers at doctor visits, a total of 112–160 participants would be required. Based on previous studies, a total of 60–150 patients (3–5 per oncologist) are then needed in the baseline phase.27

Although the total time devoted to CST for the oncologists in this study is reduced from the original SHARE-CST programme, the role-plays for individual participants are performed the same time, and communication coaching with QPL for the patients is added. Therefore the effect size from the previous study was adopted for sample size calculation, and 20 oncologists, 3 patients per oncologist, a total of 60 patients in the baseline phase, and 10 patients per oncologist, for a total of 200 patients, are enrolled in the follow-up phase (figure 1).

Patient and public involvement

This study protocol was co-designed by a patient with pancreatic cancer and a family member of a patient with pancreatic cancer who participated as researchers. They spoke with other patients to help develop recommendations for when patients’ preferences and/or opinions should be considered. They will play a similar role in the implementation of the study. Thus, patients were and will continue to be involved in the study. The results of this study will be available via a study website.

Data analysis

Primary analyses

To examine the intervention effect parameters of all randomly assigned subjects in the primary analysis set according to the ITT principle, we will analyse the primary outcome with SHARE-RE as an indicator of enhanced empathic communication using a generalised linear model. The primary outcome of interest is the difference in SHARE-RE scores between the two groups after intervention. A two-sided p<0.05 will be used to indicate statistical significance.

Secondary analyses

We will perform secondary analyses to supplement our primary analysis and obtain a clearer understanding of our clinical questions. The secondary analyses will use models similar to that of the primary analysis and will examine data for the secondary outcome measures. These analyses will be conducted for exploratory purposes.

Interim analyses

No interim analysis is planned.

Publication policy

The protocol and study results will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals. The first author of the main paper will be a member of the steering committee (the authors of the protocol paper). Another person could be the first author if approved by the steering committee. The list of coauthors will be determined before submitting each paper.

Study period

The study period of this trial is April 2017– March 2023; the registration period is August 2018–July 2020.

Ethics and dissemination

The present study is subject to ethical guidelines for clinical studies published by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the modified Act on the Protection of Personal Information, as well as the ethical principles established for research on humans stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and further amendments thereto. If important protocol modifications are needed, the investigators will discuss them and report to the review board for approval. Regarding dissemination, the results obtained will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. The main and/or relevant findings will be presented at conferences.

Discussion

This study is a multisite RCT to evaluate the efficacy of an integrated communication support programme for patients with rapidly progressive advanced cancer, caregivers and oncologists to promote patient-centred communication. The intervention programme is unique in intervening with both oncologists and patients/caregivers for a brief time at the point of first-line chemotherapy, before they are critically ill.

In clinical oncology, the introduction of personalised precision medicine has allowed great therapeutic progress. Patient–oncologist communication is uncertain and complex, and busy oncologists often find it difficult to take extra time with their patients. As a result, personalised and precise communication between a patient and an oncologist may not be achieved. If empathic communication between patients and oncologists can be improved, including shared decision-making based on patient values and preferences about the use of evidence-based medicine, the result can be an effective integration of best practices and patient values, allowing for better use of clinical expertise and available resources.

In this study, it is essential that intervention facilitators and SPs be well trained to maintain the quality of the intervention. In the future, it may be possible to reduce costs by developing internet-based programmes. Regarding QPL, clinical benefits may increase when it is possible to link medical records with data from wearable devices. Above all, the use of electronic media is expected to make implementation of the intervention programme easier.

Strengths and limitations

This study has two methodological limitations. First, the intervention programme for both oncologists and patients/caregivers is complex, consisting of multiple factorial components. Thus, if the interventions prove superior to usual care, we will not be able to determine which interventions and components are most efficacious or beneficial in promoting communication. Second, patient intervention will be applied only to patients with pancreatic cancer. The generalisation potential of the approach for other cancers is thus unknown. However, as pancreatic cancer is one of the most rapidly progressing cancers, if the intervention is effective for patients with pancreatic cancer who have severe physical and psychological conditions, it may be applied to patients with other cancers as well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T Mashiko and M Kurosaki for their data management support. We also thank members of PanCan Japan, S Furutani, Dr M Mori, Dr Y Shirai, Dr S Umezawa, N Inomata, M Umehashi, Dr M Okamura, Dr M Odawara, Dr A Hanai, R Soga, R Sugihara, T Akiyama and M Kanamaru for their support for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MF is the principal investigator. MF and YU developed the CST program. MF, AS, SJ, TO, YM and YU developed the QPL. MF, TO, TY, MI, MU, MO, YT, TM, YM and YU participated in the design of this study. All authors prepared the protocol and agreed with the final protocol and revisions. MF, AS, SJ, MT prepared the investigators brochure and CRFs. TY played a chief role in the statistical parts. TM played a role in data management. MF drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP 17ck0106237h0001) and in part by The National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (30-A-11).

Disclaimer: This funding source had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health Labour and welfare, Japan: white papers & reports annual health, labour and welfare report, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Center Japan: cancer statistics in Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. . A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:81–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otani H, Morita T, Esaki T, et al. . Burden on oncologists when communicating the discontinuation of anticancer treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;41:999–1006. 10.1093/jjco/hyr092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. . Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–73. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. . Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al. . Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 1998;279:1709–14. 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med 2002;16:297–303. 10.1191/0269216302pm575oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. . Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1005–53. 10.1093/annonc/mdi211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein RM, Peters E. Beyond information: exploring patients’ preferences. JAMA 2009;302:195–7. 10.1001/jama.2009.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Matsushima E, et al. . Preferences of advanced cancer patients for communication on anticancer treatment cessation and the transition to palliative care. Cancer 2015;121:4240–9. 10.1002/cncr.29635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. . Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2166–72. 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sep MSC, van Osch M, van Vliet LM, et al. . The power of clinicians’ affective communication: how reassurance about non-abandonment can reduce patients’ physiological arousal and increase information recall in bad news consultations. An experimental study using analogue patients. Patient Educ Couns 2014;95:45–52. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo-Soto GA, et al. . Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD003751. 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiefel F, Kiss A, Salmon P, et al. . Training in communication of oncology clinicians: a position paper based on the third consensus meeting among European experts in 2018. Ann Oncol 2018;29:2033–6. 10.1093/annonc/mdy343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. . Patient-clinician communication: American society of clinical oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3618–32. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimori M, Akechi T, Morita T, et al. . Preferences of cancer patients regarding the disclosure of bad news. Psychooncology 2007;16:573–81. 10.1002/pon.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: a systematic literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2009;39:201–16. 10.1093/jjco/hyn159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, et al. . Development and preliminary evaluation of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communicating bad news. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:379–86. 10.1017/S147895151300031X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang W-R, Chen K-Y, Hsu S-H, et al. . Effectiveness of Japanese SHARE model in improving Taiwanese healthcare personnel's preference for cancer truth telling. Psychooncology 2014;23:259–65. 10.1002/pon.3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada Y, Fujimori M, Shirai Y, et al. . Changes in physicians’ intrapersonal empathy after a communication skills training in Japan. Acad Med 2018;93:1821–6. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, et al. . Patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann Oncol 1994;5:199–204. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandes K, Linn AJ, Butow PN, et al. . The characteristics and effectiveness of question prompt list interventions in oncology: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology 2015;24:245–52. 10.1002/pon.3637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirai Y, Fujimori M, Ogawa A, et al. . Patients’ perception of the usefulness of a question prompt sheet for advanced cancer patients when deciding the initial treatment: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychooncology 2012;21:706–13. 10.1002/pon.1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujimori M, Akechi T, Akizuki N, et al. . Good communication with patients receiving bad news about cancer in Japan. Psychooncology 2005;14:1043–51. 10.1002/pon.917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, et al. . Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1090–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdm068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Weert JCM, Jansen J, Spreeuwenberg PMM, et al. . Effects of communication skills training and a question prompt sheet to improve communication with older cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011;80:145–59. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. . Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: the voice randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:92–100. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, et al. . Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-PRO extension. JAMA 2018;319:483–94. 10.1001/jama.2017.21903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, et al. . Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer 2001;85:1273–9. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roter DL, et al. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:1877–84. 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430170071009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. . The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyashita M, Wada M, Morita T, et al. . Development and validation of the comprehensive quality of life outcome (CoQoLo) inventory for patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:75–83. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hillen MA, Postma R-M, Verdam MGE, et al. . Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the trust in oncologist scale-the trust in oncologist scale-short form (TiOS-SF). Support Care Cancer 2017;25:855–61. 10.1007/s00520-016-3473-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zandbelt LC, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, et al. . Satisfaction with the outpatient encounter: a comparison of patients' and physicians' views. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1088–95. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30420.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mack JW, Nilsson M, Balboni T, et al. . Peace, equanimity, and acceptance in the cancer experience (PEACE): validation of a scale to assess acceptance and struggle with terminal illness. Cancer 2008;112:2509–17. 10.1002/cncr.23476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, et al. . Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2014;120:278–85. 10.1002/cncr.28369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. . Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, et al. . Good death inventory: a measure for evaluating good death from the bereaved family member’s perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:486–98. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.