Abstract

Objectives

We sought to map the evidence and identify interventions that increase initiation of antiretroviral therapy, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for people living with HIV at high risk for poor engagement in care.

Methods

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews and sought for evidence on vulnerable populations (men who have sex with men (MSM), African, Caribbean and Black (ACB) people, sex workers (SWs), people who inject drugs (PWID) and indigenous people). We searched PubMed, Excerpta Medica dataBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library in November 2018. We screened, extracted data and assessed methodological quality in duplicate and present a narrative synthesis.

Results

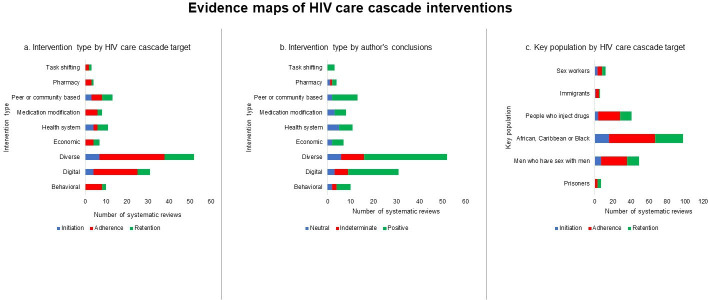

We identified 2420 records of which only 98 systematic reviews were eligible. Overall, 65/98 (66.3%) were at low risk of bias. Systematic reviews focused on ACB (66/98; 67.3%), MSM (32/98; 32.7%), PWID (6/98; 6.1%), SWs and prisoners (both 4/98; 4.1%). Interventions were: mixed (37/98; 37.8%), digital (22/98; 22.4%), behavioural or educational (9/98; 9.2%), peer or community based (8/98; 8.2%), health system (7/98; 7.1%), medication modification (6/98; 6.1%), economic (4/98; 4.1%), pharmacy based (3/98; 3.1%) or task-shifting (2/98; 2.0%). Most of the reviews concluded that the interventions effective (69/98; 70.4%), 17.3% (17/98) were neutral or were indeterminate 12.2% (12/98). Knowledge gaps were the types of participants included in primary studies (vulnerable populations not included), poor research quality of primary studies and poorly tailored interventions (not designed for vulnerable populations). Digital, mixed and peer/community-based interventions were reported to be effective across the continuum of care.

Conclusions

Interventions along the care cascade are mostly focused on adherence and do not sufficiently address all vulnerable populations.

Keywords: HIV & AIDS, therapeutics, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first overview to address the whole cascade of care for people living with HIV.

Our categorisation of systematic reviews by intervention type and the intervention’s success will permit decision makers to easily identify the interventions that are likely to work for their specific context.

We categorised systematic reviews to facilitate data synthesis, however we acknowledge that certain interventions may fit into multiple categories.

Among mixed interventions, it was challenging to determine the role of the individual intervention types on the overall effect.

This report at the systematic review level does not cover all aspects of the interventions, which can only be retrieved from individual trials.

Background

Despite advances in diagnosis and management of HIV infection, many people living with HIV still do not have optimal outcomes. In 2014, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) set the 90-90-90 target for 2020.1 If this target is met, 90% of people living with HIV will know their HIV status; 90% of all people diagnosed with HIV will be receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) and 90% of all people on ART will be virally suppressed.1 These targets are contingent on engagement in the cascade of care that includes access to testing, timely diagnosis, access to and initiation of treatment, adherence to treatment and retention in care. Despite national efforts, very few countries have actually met these targets.2 The UK has met these targets3 and Botswana and Australia are on track.4 Canada is also on track to meet these targets, with 87% of people with HIV diagnosed, 82% on treatment and 93% virally suppressed.5 For countries to meet these targets, there must be policies in place to support programmes that deliver interventions across the entire cascade of care. As such, there must be awareness, reductions in stigma and incentives that promote testing alongside strategies to enhance treatment initiation, adherence and retention in care.6 Consistent access to ART and high-quality data should be collected so that advances towards the targets can be measured appropriately.6

If all these conditions are met and countries meet these targets, there are still concerns that the targets may be met at a national level but not in certain subpopulations.7 8 The literature suggests that vulnerable populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers (SWs), people who inject drugs (PWID), people with precarious migration status and ethno-racial minorities have a higher disease burden, worse engagement in care and are less likely to achieve viral suppression.9–14 MSM and SWs all over the world are 19 and 13.5 times more likely to be living with HIV.7 8 In Canada, inequities in social and structural determinants such as injection drug use, ethno-racial background, age, housing, sex work and gender affect engagement in care.11–15

The literature is rife with interventions aimed at improving different aspects of the care cascade. However, the challenges countries face in achieving the UNAIDS targets suggest that the interventions may not be effective, may not be properly translated into practice or may not be tailored (designed to have optimal impact on groups with different sociodemographic or risk characteristics that could influence the effect of the intervention) to the relevant populations. Therefore, due consideration of the settings in which interventions are tested, their target populations, complexity and applicability in the real world are important considerations for scale up.16 17 These limitations in the quality and quantity of evidence were identified in the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care guideline document.18

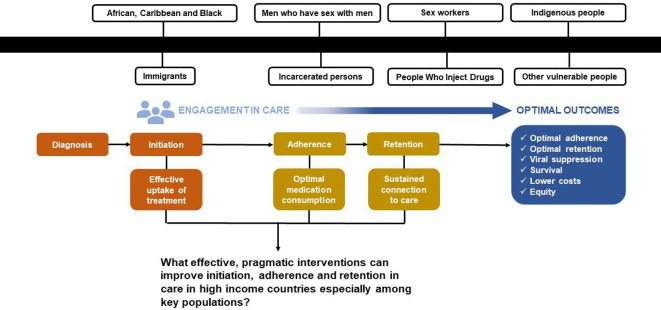

While HIV is still a leading cause of disease burden in sub-Saharan Africa,19 vulnerable populations in high-income countries may experience a comparable disease burden if they are not recognised as a priority.20 As countries strive to meet the 90-90-90 target, it is becoming apparent that due to the disparities in outcomes across jurisdictions and populations, better targeted approaches are required to improve engagement in care.21 Ontario is the most populous province of Canada and home to 42% of Canada’s 71 000 people living with HIV. Due to individual, social and structural factors, it is estimated that approximately 20% of these people living with HIV in Canada have discontinuous care.11 In Ontario, 80%–87% of people living with HIV are in care, 70%–82% are on ART and 67%–81% are virally suppressed.22 This overview of systematic reviews will inform policy, practice and research in Ontario and other high-income settings especially with regards to engagement in HIV care for vulnerable populations. We sought to map the available evidence on strategies that improve engagement in the HIV care cascade (initiation of treatment, adherence to medication and retention in care) for priority populations as well as to identify knowledge gaps (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of the HIV care cascade.

This overview is the first part of our report and includes a high-level summary of the findings from systematic reviews, with no distinction by country. We provide a map of the evidence here, and the second part will summarise the findings from the randomised trials included in the systematic reviews.

Methods

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews using standard Cochrane methods.23 The protocol for this overview has been published elsewhere.24 Key features of our methods are outlined below.

Patient and public involvement

Our research question was formulated and refined based on input from the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN), a non-profit network, as part of their strategy to close gaps in the cascade of care for key populations. The investigators include patients, clinicians, researchers and representatives of AIDS Service Organisations/Community-Based Organisations. Decision makers and representatives from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care of Ontario were also consulted.

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

We included any systematic reviews with at least one study with a randomised comparison of an intervention designed to improve initiation of ART, adherence to ART and/or retention in care among people living with HIV. We excluded abstracts, non-systematic reviews and other overviews. All comparators (eg, attention control, usual care, another intervention) were eligible for inclusion. We had no restriction on the location of the studies or the ages of the participants.

Search methods for identification of reviews

We conducted an exhaustive and comprehensive search of the following databases: PubMed, Excerpta Medica dataBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library; from 1995 (when combination ART was introduced) to 13 November 2018. The search strategy was reviewed by a librarian at Health Sciences Centre Library at McMaster University. The full search strategy is reported as a supplemental file (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjopen-2019-034793supp001.pdf (84.2KB, pdf)

We also searched the websites of the WHO, UNAIDS, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the systematic review database housed at the OHTN: Synthesised HIV/AIDS Research Evidence (http://www.hivevidence.ca/frmSearch.aspx).

Finally, we looked for additional systematic reviews in the bibliographies of the included reviews.

Screening

The results of our search were collated in EndNote reference manager.25 Duplicates were removed and all the references were uploaded unto DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). We screened the retrieved citations in duplicate with reviewer pairs (BZ, AW, AH) first by examining the titles and abstracts and second by examining the full texts. Systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria were processed and data were extracted.

Data items

From the systematic reviews, we extracted standard bibliometric data (author, year), number of included primary studies and their designs, target populations, types of interventions, outcomes of interest, key findings and knowledge gaps. Data were extracted in duplicate by reviewers working in pairs (BZ, AW, AH).

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

We appraised the methodological quality of the included reviews using the risk of bias in systematic reviews tool.26 This tool allows reviewers to assess the relevance of the question, identify concerns with the review process and make a judgement on risk of bias (high, low, unclear). Risk of bias was appraised in duplicate by pairs of reviewers (BZ, AW, AH).

Discrepancies and disagreements in screening, data extraction and risk of bias were resolved by consensus or by adjudication by a third reviewer (LM).

Data synthesis

The extracted data were described narratively. Systematic reviews were organised according to the portion of the care cascade they addressed (ie, initiation, adherence, retention) and the intervention types: behavioural or educational, digital, mixed, economic, health system, medication modification, peer or community based, pharmacy based or task-shifting. These categories were developed post-hoc to facilitate data synthesis. The types of interventions included in each category are outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Categorisation of intervention types in the systematic reviews

| Intervention category | Types |

| Behavioural and educational | Medication-assisted therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, motivational interviewing, psychotherapy, relaxation |

| Digital | Digital technology-based interventions such as alarms, electronic pillboxes and pagers, mobile device text messages and voice messages, computer-based or internet-based interventions, online support communities and electronic medication packaging |

| Mixed | Combinations of any of the listed categories |

| Economic | Food assistance, cash incentives, performance-based financing, household economic strengthening |

| Health system | Point-of-care services, decentralised services, less frequent visits |

| Medication modification | Single tablet regimens, fixed dose combinations, rapid medication initiation, observed therapy |

| Peer or community based | Homebased care, community-based services including the use of community health workers, lay health workers, treatment buddies, field officers, peer educators, volunteers and counsellors |

| Pharmacy based | Changes to standard pharmacy service delivery, pharmacist delivered interventions |

| Task-shifting | Service delivery by non-doctor staff, nurse-led interventions |

Conclusion statements were categorised according to a previously used framework: positive (evidence of effectiveness); neutral (no evidence of effectiveness or no opinion); negative (authors advise against the use of intervention); indeterminate (insufficient evidence or more research is required).27 Knowledge gaps were operationalised according to guidance on how to report research recommendations by identifying the state of the evidence, participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes for which further research is needed.28 We also discuss our findings within the scope of the Health Systems Arrangement Framework.29 In this framework, interventions may be organised to inform different parts of the decision-making process, and interventions can be related to governance, financial or delivery arrangements.29 Intervention effects are summarised according to the vulnerable population they were tested with, intervention target (initiation, adherence, retention) and risk of bias. Interventions reported in systematic with positive recommendations are highlighted. Our findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.30

Results

Literature search

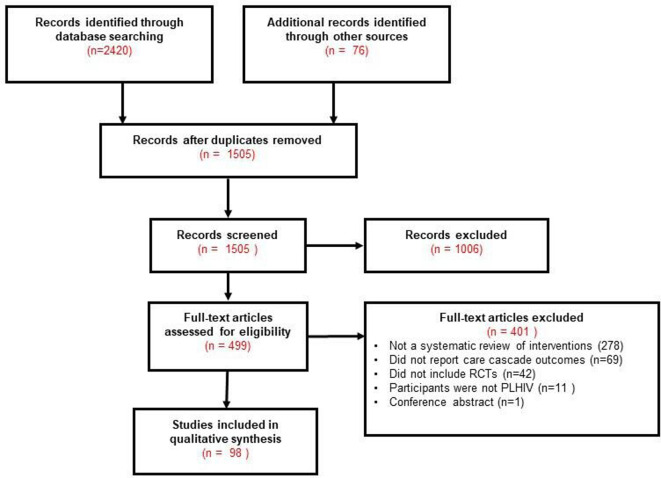

Our search identified 2420 records from electronic databases and 76 from other sources. After removal of duplicates, 1505 titles and abstracts were screened, of which 1006 were considered ineligible and excluded. We further screened 499 full-text articles and included 98. Agreement on the screening of full-text articles was high (Kappa=0.79). The screening process is outlined in a PRISMA flow diagram (figure 2).30 A full list of excluded systematic reviews is provided as a supplemental file (online supplemental appendix 2).

Figure 2.

Systematic review flow diagram. PLHIV, people living with HIV; RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

bmjopen-2019-034793supp002.pdf (250.9KB, pdf)

Description of included reviews

The 98 included systematic reviews were published between 2006 and 201831–128 and reported on interventions to improve initiation of care (n=18),32 41 54 58 61 64 65 70 75 78 81 84 92 100 109 113 123 126 adherence to ART (n=82)31–36 38 39 41–53 55 57 59 60 62 65–68 71–77 79–108 110–112 114–116 118–122 124 125 127 128 and retention in care (n=39).32 37 40 41 52 56 58–60 63–66 68–70 75–78 81 84 86 88 89 91–93 95 96 100 101 105 113 115–117 126 128 Thirty-one (31) reviews reported two or more aspects of the cascade.32 41 52 58–60 64–66 70 75–78 81 84 86 88 89 91 92 95 96 100 101 105 113 115 116 126 128 They included a median (quartile 1; quartile 3 (Q1; Q3)) of 19 (11; 28) primary studies and 8 (4; 13) randomised trials.

With regards to vulnerable populations, 32.7% (32/98) included primary studies involving MSM,31 33 40–42 45 47 48 51 52 59 65 70 73 80 81 85 87 89 92 96 98–100 104–106 108 110 113 114 119 67.3% (66/96) involving African, Caribbean or Black (ACB) people,31–34 36 37 40 43 45 47 48 50 52–54 56 58–61 63–66 70 71 73–82 84–87 89 90 92 93 95 101–104 106 108–110 112–120 123 125 126 128 25.5% (25/98) focused on PWID,39 41 43 44 48 50–52 60 66 68 70 73 74 85 88 91 92 96 99 100 105 108 116 121 6.1% (6/98) involving SW,41 42 48 52 96 100 4.1% (4/98) included data on immigrants42 82 108 126 and 4.1% (4/98) included data on incarcerated persons.40 60 91 105 These characteristics are summarised in table 2. A full list of the 98 included systematic reviews is reported as a supplemental file (online supplemental appendix 3).

Table 2.

Summary characteristics of included systematic reviews: n=98

| Variable | Statistic |

| Year: median (quartile 1; quartile 3) | 2015 (2013; 2017) |

| Number of included primary studies: median (quartile 1; quartile 3) | 29 (11; 28) |

| Number of randomised trials: median (quartile 1; quartile 3) | 8 (4; 13) |

| Vulnerable populations included: n (%) | |

| African, Caribbean or Black | 66 (67.3) |

| Men who have sex with men | 32 (32.7) |

| People who inject drugs | 25 (25.5) |

| Sex workers | 6 (6.1) |

| Immigrants | 4 (4.1) |

| Incarcerated persons | 4 (4.1) |

| Intervention categories: n (%) | |

| Mixed | 37 (37.8) |

| Digital | 22 (22.4) |

| Behavioural or educational | 9 (9.2) |

| Peer or community based | 8 (8.2) |

| Health system | 7 (7.1) |

| Medication modification | 6 (6.1) |

| Economic | 4 (4.1) |

| Pharmacy | 3 (3.1) |

| Task-shifting | 2 (2.0) |

| Care cascade outcomes: n (%) * | |

| Adherence | 82 (59.0) |

| Retention | 39 (28.1) |

| Initiation | 18 (12.9) |

*Not mutually exclusive.

bmjopen-2019-034793supp003.pdf (163.6KB, pdf)

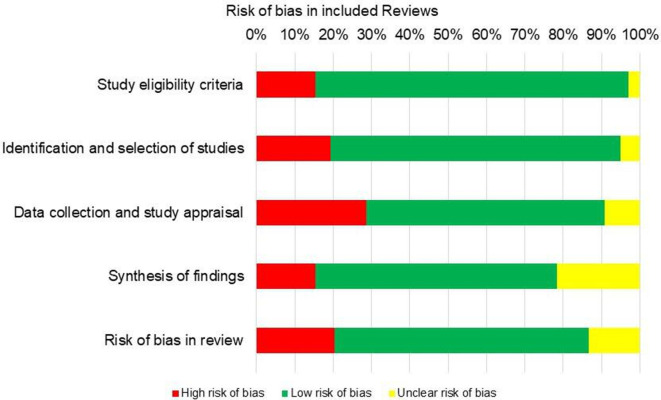

Methodological quality of included reviews

Most of the systematic reviews were judged to be a low risk of bias (65 (66.3%)). Twenty (20.4%) were judged to be at high risk of bias and 13 (13.3%) were judged to be at unclear risk of bias. The most frequent concern was related to data collection and primary study appraisal (28.6% at high risk of bias in this domain). The main concerns we identified were no risk of bias assessments conducted, missing primary study information and no evidence that data had been processed in duplicate. This was followed by the risk of bias in the identification and selection of primary studies (19.4% at high risk of bias in this domain). The main limitations we identified were not searching grey literature, searching less than two databases, exclusion of non-English primary studies, no evidence that data were processed in duplicate and not reporting the search strategy. For the domain of study eligibility criteria (15.3% at high risk of bias in this domain) the main concerns were: eligibility criteria not described in sufficient detail, ambiguous criteria and restrictions based on publication status and language. For the domain of synthesis and findings (15.3% at high risk of bias in this domain) the main concerns were: heterogeneity was not assessed, choice of synthesis approach not justified and primary study biases not addressed (see figure 3 and online supplemental appendix 3).

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary.

Effects of interventions

Most systematic reviews gave positive recommendations for the interventions they examined (69/70.4%). Seventeen (17.3%) were neutral and 12 (12.2%) were indeterminate. No systematic reviews recommended against any interventions. Positive findings from systematic reviews are outlined below. All our findings, positive, negative, neutral and indeterminate are summarised in a supplemental file (online supplemental appendix 3).

Initiation

Of the 18 systematic reviews that examined initiation of ART as an outcome, 11 (61.1%) at low risk of bias reported that digital,41 100 mixed,32 54 75 84 health system66 78 123 and peer-based or community-based interventions65 113 improved initiation of ART. Two systematic reviews at high or unclear risk of bias reported that digital64 and mixed interventions improved initiation of ART.70

Adherence

Of the 82 systematic reviews that examined adherence to ART as an outcome, 25 (30.5%) at low risk of bias reported that behavioural/educational,44 45 digital,31 33 41 46 52 79 98 100 101 111 122 mixed,32 36 43 53 57 62 72 74 75 82 84 91 103 105 108 112 health system,50 medication modification,49 59 102 peer/community-based,73 96 128 pharmacy-based86 111 and task-shifting interventions77 improved adherence to ART. Eighteen (18/21.9%) systematic reviews at high or unclear risk of bias reported that behavioural/educational,39 104 digital,42 71 85 90 mixed,50 80 89 99 114 127 economic,55 68 116 medication modification,97 peer-based or community-based125 and task-shifting118 interventions improved adherence to ART.

Retention

Of the 39 systematic reviews that examined retention in care as an outcome, 21 (53.8%) systematic reviews at low risk of bias reported that digital,41 52 100 mixed,32 66 69 75 84 91 105 economic,115 health system,66 78 95 medication modification,59 peer/community-based65 96 113 128 and task-shifting77 interventions improved adherence to HIV care. Seven (7/17.9%) of systematic reviews at high or unclear risk of bias reported that behavioural/educational,37 digital,64 mixed,70 89 economics,116 health system40 and peer-based or community-based interventions56 improved retention in care.

Figure 4 is a display of the available evidence, showing intervention type by HIV care cascade target (panel a), intervention type by authors’ conclusions (panel b) and key population by HIV care cascade target (panel c).

Figure 4.

Evidence maps of HIV care cascade interventions.

Knowledge gaps

The most frequent knowledge gap identified in 22 (22.4%) systematic reviews was with regards to the population studied, where further investigation with vulnerable and marginalised groups such as children, youth, MSM, pregnant and breastfeeding women, individuals in low-income settings, individuals with concurrent mental health issues and older adults is required. The authors also raised concerns about the primary study designs (n=22/22.4%) and primarily called for more robust, innovative, rigorous and high-quality designs, including experimental designs, (pragmatic) randomised trials, longer follow-up times, mixed methods approaches and primary studies with larger sample sizes. The nature of the intervention was also identified as a knowledge gap (22/22.4%). The authors found that interventions were not sufficiently tailored to high-risk populations, low-income settings, were too costly or did not cover the entire cascade of care. They further suggested that novel interventions be investigated and older intervention be combined to assess synergistic effects. Only two (2.0%) systematic reviews raised concerns about the nature of the outcomes used.72 83 They called for universal definitions for adherence and the use of more humanistic, economic and patient-important outcomes.

Discussion

We conducted an exhaustive and comprehensive search for systematic reviews focused on examining interventions that enhance ART initiation, ART adherence and retention among people living with HIV. We included 98 systematic reviews. Most of the systematic reviews we identified focused on adherence-enhancing interventions and investigated a mixed range of intervention categories. For the most part, the authors of the included systematic reviews found that the interventions were effective (70.4%). Digital, mixed and peer/community-based interventions were the only three categories of interventions that were reported to be effective across the whole continuum of care. The main knowledge gaps identified in most systematic reviews was a lack of focus on the populations that would benefit the most (22.4%), poor quality of the primary studies (22.4%) and nature of the interventions (22.4%).

We further examined to what extent health systems arrangements were met by this body of evidence. Most systematic reviews focused on the delivery of interventions (task-shifting, homebased care, pharmacy-based interventions) but none addressed governance of HIV care and very few addressed financial components (food assistance, cash incentives, performance-based financing, household economic strengthening) that may support or hinder access to HIV care and treatment.55 68 115 116 This may be an important limitation in how research is designed, without adequate consideration of the facets of a health system that could influence outcomes.

Most of the systematic reviews were at low risk of bias (66.3%).26 However, there were some concerns, notably with issues related to reporting of details in review conduct which indicated high or unclear risk of bias. We recognise that journal word count limitations may prevent authors from reporting all the relevant details, but appendices could be used to provide additional details. Risk of bias from these systematic reviews should be interpreted in context and may differ from the risk of bias in the primary studies included.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no other overview of systematic reviews investigating the cascade of HIV care, but our findings confirm previous research indicating a paucity of research on vulnerable populations129 and challenges with scaling-up interventions.130

The disproportionate study of adherence might be due to its perceived importance as a cornerstone of care or the relative ease of designing adherence studies. Prior to recent recommendations to treat all diagnosed people, initiation of treatment was seldom a priority.131 Likewise, retention in care is an outcome that requires substantially longer follow-up to generate meaningful results.11 132 In order for countries to meet the 90-90-90 target, the cascade of care must be viewed as continuum, not just for practice, but also for research, such that interventions that strengthen the entire cascade be scaled up.

Even though only disparate definitions of adherence to ART were identified by the authors of some systematic reviews, we believe such diversity may exist with retention in care, as other studies have noted that there is no gold standard for what constitutes adequate retention.133 Future work on the trials included in the systematic reviews will permit us to describe the breadth of definitions used for both adherence and retention. Standardised definitions are important for jurisdictions to be able to measure changes over time and make cross jurisdictional comparisons. Standardised definitions will also help systematic reviewers to synthesise research.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge the following limitations. Despite our attempt to group the interventions into categories, we recognise that certain interventions may fit into more than one category. For example, tasking-shifting and pharmacy-based interventions can be viewed as health system or community-based interventions. Second, for the group of systematic reviews that investigated mixed interventions, it is challenging to determine the role of the individual intervention types on the overall effect. This group could contain interventions from any category and therefore it is not surprising that the systematic reviews that included mixed interventions often found a significant effect. Within each systematic review, the diversity of study designs, populations and primary studies from various income levels precluded in-depth investigation of how these issues may have affected intervention effectiveness at the systematic review level. No distinction was made between ACB populations in their respective countries versus ACB populations in high-income countries where the vulnerability is different. Further ongoing work on the trials included in these systematic reviews will highlight the features of interventions in ACB populations. Some primary studies are included in more than one systematic review. This highlights the need for a primary study-level analysis. Also, we reiterate that the statements on effectiveness are drawn from the concluding statements from the included systematic reviews and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Finally, despite our efforts to conduct a comprehensive and exhaustive search, it is possible that some systematic reviews were missed if they were indexed with terms we did not include in our strategy.

This work has many strengths. In addition to using a predefined protocol, we conducted a comprehensive search, assessed risk of bias, investigated the availability of data on vulnerable populations and categorised the systematic reviews by type of intervention and success of the intervention. This approach would permit decision makers and other end users to identify intervention type that are likely to work for specific populations at each point of the care cascade. However, a trial-level analyses is required to enrich these findings.

Conclusion

We found limited research on vulnerable populations and uneven focus on the three aspects of the care cascade. In order to identify the most effective and pragmatic interventions for vulnerable populations in high-income settings, a study-level analysis is required. The diversity of the interventions examined and the populations studied indicate the need for network meta-analyses in this field, some of which have already been published.90 The lack of systematic reviews that generate evidence on governance is indicative of how removed many research endeavours are from policy-making. Monitoring and evaluation also need to be considered within systems to support up-to-date collection of data on detection, initiation, adherence and retention in care.

Differences between protocol and review

There are a few differences between this report and the protocol. First, after additional consultation with stakeholders, we included interventions targeting initiation of ART. Given the amount of data, we decided to report our findings on two levels, the systematic review level and the primary study level. Only the systematic review level is reported here, and therefore in-depth analyses of the settings (high vs low income) of the primary studies and the levels of pragmatism, and certainty of the evidence are reserved for a second paper.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LM developed the first draft of the manuscript. AH, AW, LM and BZ extracted data and created tables. EA, DOL, BR, MS, DM, LPR, CL, SM, ACB, WH, AH, AW, BZ and LT revised several versions of the manuscript and approved the final version. LM is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by The Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) grant number EFP-1096-Junior Inv.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

References

- 1.UNAIDS 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. secondary 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic, 2014. Available: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf

- 2.Levi J, Raymond A, Pozniak A, et al. . Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000010. 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirby T. The UK reaches UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. Lancet 2018;392:2427. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33117-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marukutira T, Stoové M, Lockman S, et al. . A tale of two countries: progress towards UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets in Botswana and Australia. J Int AIDS Soc 2018;21:e25090. 10.1002/jia2.25090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canada Go Summary: measuring Canada's progress on the 90-90-90 HIV targets. secondary summary: measuring Canada's progress on the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 2017. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-measuring-canada-progress-90-90-90-hiv-targets.html

- 6.Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on "Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades". BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000227–27. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baral S, Sifakis F, Cleghorn F, et al. . Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000-2006: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e339. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. . Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:538–49. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cescon AM, Cooper C, Chan K, et al. . Factors associated with virological suppression among HIV-positive individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy in a multi-site Canadian cohort. HIV Med 2011;12:352–60. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CATIE The epidemiology of HIV in Canada. secondary the epidemiology of HIV in Canada, 2017. Available: http://www.catie.ca/en/fact-sheets/epidemiology/epidemiology-hiv-canada

- 11.Rachlis B, Burchell AN, Gardner S, et al. . Social determinants of health and retention in HIV care in a clinical cohort in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Care 2017;29:828–37. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1271389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph B, Kerr T, Puskas CM, et al. . Factors linked to transitions in adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Care 2015;27:1128–36. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1032205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr T, Palepu A, Barness G, et al. . Psychosocial determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users in Vancouver. Antivir Ther 2004;9:407–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lourenço L, Nohpal A, Shopin D, et al. . Non-Hiv-Related health care utilization, demographic, clinical and laboratory factors associated with time to initial retention in HIV care among HIV-positive individuals linked to HIV care. HIV Med 2016;17:269–79. 10.1111/hiv.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tapp C, Milloy M-J, Kerr T, et al. . Female gender predicts lower access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a setting of free healthcare. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:86–7. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker PM, Reid A, Schall MW. A framework for scaling up health interventions: lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implementation Sci 2015;11 10.1186/s13012-016-0374-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willis CD, Riley BL, Stockton L, et al. . Scaling up complex interventions: insights from a realist synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst 2016;14:88. 10.1186/s12961-016-0158-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. . Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an international association of physicians in AIDS care panel. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:817–33. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, et al. . Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nature 2019;570:189–93. 10.1038/s41586-019-1200-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rights of vulnerable people and the future of HIV/AIDS. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:67. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter K, Gourlay A, Attawell K, et al. . Substantial heterogeneity in progress toward reaching the 90-90-90 HIV target in the who European region. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;79:28–37. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.OHESI Hiv care cascade in Ontario: linkage to care, in care, on antiretroviral treatment, and virally suppressed, 2015. secondary HIV care cascade in Ontario: linkage to care, in care, on antiretroviral treatment, and virally suppressed, 2015, 2015. Available: http://www.ohesi.ca/documents/OHESI-cascade-report-17072017-a2.pdf

- 23.Becker LA, Oxman AD. Overviews of reviews. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Cochrane book series, 2008: 607–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mbuagbaw L, Mertz D, Lawson DO, et al. . Strategies to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for people living with HIV in high-income countries: a protocol for an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022982. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuters. T Endnote X7. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Thomson Reuters, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, et al. . ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:225–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tricco AC, Antony J, Vafaei A, et al. . Seeking effective interventions to treat complex wounds: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Med 2015;13:89. 10.1186/s12916-015-0288-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown P, Brunnhuber K, Chalkidou K, et al. . How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ 2006;333:804–6. 10.1136/bmj.38987.492014.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavis JN, Røttingen J-A, Bosch-Capblanch X, et al. . Guidance for evidence-informed policies about health systems: linking guidance development to policy development. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001186. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Altman DG, Liberati A, et al. . PRISMA statement. Epidemiology 2011;22:128. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181fe7825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amankwaa I, Boateng D, Quansah DY, et al. . Effectiveness of short message services and voice call interventions for antiretroviral therapy adherence and other outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0204091. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambia J, Mandala J. A systematic review of interventions to improve prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission service delivery and promote retention. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20309. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anglada-Martinez H, Riu-Viladoms G, Martin-Conde M, et al. . Does mHealth increase adherence to medication? results of a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:9–32. 10.1111/ijcp.12582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arrivillaga M, Martucci V, Hoyos PA, et al. . Adherence among children and young people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review of medication and comprehensive interventions. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud 2013;8:321–37. 10.1080/17450128.2013.764031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bain-Brickley D, Butler LM, Kennedy GE, et al. . Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in children with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;18 10.1002/14651858.CD009513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bärnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, et al. . Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:942–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bateganya MH, Amanyeiwe U, Roxo U, et al. . Impact of support groups for people living with HIV on clinical outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatta DN, Liabsuetrakul T, McNeil EB. Social and behavioral interventions for improving quality of life of HIV infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:80. 10.1186/s12955-017-0662-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Binford MC, Kahana SY, Altice FL. A systematic review of antiretroviral adherence interventions for HIV-infected people who use drugs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9:287–312. 10.1007/s11904-012-0134-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brennan A, Browne JP, Horgan M. A systematic review of health service interventions to improve linkage with or retention in HIV care. AIDS Care 2014;26:804–12. 10.1080/09540121.2013.869536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, et al. . Social media interventions to promote HIV testing, linkage, adherence, and retention: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e394. 10.2196/jmir.7997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catalani C, Philbrick W, Fraser H, et al. . mHealth for HIV Treatment & Prevention: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Open AIDS J 2013;7:17–41. 10.2174/1874613620130812003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaiyachati KH, Ogbuoji O, Price M, et al. . Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a rapid systematic review. AIDS 2014;28 Suppl 2:S187-204–204. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang SJ, Choi S, Kim S-A, et al. . Intervention strategies based on Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills model for health behavior change: a systematic review. Asian Nurs Res 2014;8:172–81. 10.1016/j.anr.2014.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charania MR, Marshall KJ, Lyles CM, et al. . Identification of evidence-based interventions for promoting HIV medication adherence: findings from a systematic review of U.S.-based studies, 1996-2011. AIDS Behav 2014;18:646–60. 10.1007/s10461-013-0594-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Checchi KD, Huybrechts KF, Avorn J, et al. . Electronic medication packaging devices and medication adherence: a systematic review. JAMA 2014;312:1237–47. 10.1001/jama.2014.10059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho H, Iribarren S, Schnall R. Technology-Mediated interventions and quality of life for persons living with HIV/AIDS. A systematic review. Appl Clin Inform 2017;8:348–68. 10.4338/ACI-2016-10-R-0175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Claborn KR, Fernandez A, Wray T, et al. . Computer-Based HIV adherence promotion interventions: a systematic review: translation behavioral medicine. Transl Behav Med 2015;5:294-306–306. 10.1007/s13142-015-0317-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clay PG, Yuet WC, Moecklinghoff CH, et al. . A meta-analysis comparing 48-week treatment outcomes of single and multi-tablet antiretroviral regimens for the treatment of people living with HIV. AIDS Res Ther 2018;15:17. 10.1186/s12981-018-0204-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crepaz N, Baack BN, Higa DH, et al. . Effects of integrated interventions on transmission risk and care continuum outcomes in persons living with HIV: meta-analysis, 1996-2014. AIDS 2015;29:2371–83. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crepaz N, Tungol-Ashmon MV, Vosburgh HW, et al. . Are couple-based interventions more effective than interventions delivered to individuals in promoting HIV protective behaviors? A meta-analysis. AIDS Care 2015;27:1361–6. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1112353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daher J, Vijh R, Linthwaite B, et al. . Do digital innovations for HIV and sexually transmitted infections work? results from a systematic review (1996-2017). BMJ Open 2017;7:e017604. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Bruin M, Viechtbauer W, Schaalma HP, et al. . Standard care impact on effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:240-50–50. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Jongh TE, Gurol-Urganci I, Allen E, et al. . Integration of antenatal care services with health programmes in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. J Glob Health 2016;6:010403. 10.7189/jogh.06.010403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Pee S, Grede N, Mehra D, et al. . The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav 2014;18 Suppl 5:531–41. 10.1007/s10461-014-0730-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Decroo T, Rasschaert F, Telfer B, et al. . Community-Based antiretroviral therapy programs can overcome barriers to retention of patients and decongest health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Int Health 2013;5:169–79. 10.1093/inthealth/iht016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Kristanto P, et al. . Identification and assessment of adherence-enhancing interventions in studies assessing medication adherence through electronically compiled drug dosing histories: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Drugs 2013;73:545–62. 10.1007/s40265-013-0041-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feyissa GT, Demissie TD. Effect of point of care CD4 cell count tests on retention of patients and rates of antiretroviral therapy initiation in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2014;12:395–429. 10.11124/jbisrir-2014-1383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, et al. . Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2018;32:17–23. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ford N, Nachega JB, Engel ME, et al. . Directly observed antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet 2009;374:2064–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61671-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fox MP, Rosen S, Geldsetzer P, et al. . Interventions to improve the rate or timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: meta-analyses of effectiveness. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20888. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ganguli A, Clewell J, Shillington AC. The impact of patient support programs on adherence, clinical, humanistic, and economic patient outcomes: a targeted systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:711-25–25. 10.2147/PPA.S101175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaston GB, Gutierrez SM, Nisanci A. Interventions that retain African Americans in HIV/AIDS treatment: implications for social work practice and research. Soc Work 2015;60:35–42. 10.1093/sw/swu050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Geldsetzer P, Yapa HMN, Vaikath M, et al. . A systematic review of interventions to improve postpartum retention of women in PMTCT and art care. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20679. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K, et al. . Improving engagement in the HIV care cascade: a systematic review of interventions involving people living with HIV/AIDS as Peers. AIDS Behav 2016;20:2452–63. 10.1007/s10461-016-1307-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Govindasamy D, Meghij J, Kebede Negussi E, et al. . Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings--a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:19032. 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hart JE, Jeon CY, Ivers LC, et al. . Effect of directly observed therapy for highly active antiretroviral therapy on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;54:167–79. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d9a330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrmann ES, Matusiewicz AK, Stitzer ML, et al. . Contingency management interventions for HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis control among individuals with substance use disorders: a Systematized review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;72:117–25. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higa DH, Crepaz N, Mullins MM, et al. . Identifying best practices for increasing linkage to, retention, and Re-engagement in HIV medical care: findings from a systematic review, 1996-2014. AIDS Behav 2016;20:951–66. 10.1007/s10461-015-1204-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Higa DH, Marks G, Crepaz N, et al. . Interventions to improve retention in HIV primary care: a systematic review of U.S. studies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9:313–25. 10.1007/s11904-012-0136-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Higgs ES, Goldberg AB, Labrique AB, et al. . Understanding the role of mHealth and other media interventions for behavior change to enhance child survival and development in low- and middle-income countries: an evidence review. J Health Commun 2014;19 Suppl 1:164–89. 10.1080/10810730.2014.929763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hill S, Kavookjian J. Motivational interviewing as a behavioral intervention to increase HAART adherence in patients who are HIV-positive: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care 2012;24:583–92. 10.1080/09540121.2011.630354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanters S, Park JJ, Chan K, et al. . Use of Peers to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a global network meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:21141. 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanters S, Park JJH, Chan K, et al. . Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e31–40. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30206-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keane J, Pharr JR, Buttner MP, et al. . Interventions to reduce loss to follow-up during all stages of the HIV care continuum in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1745–54. 10.1007/s10461-016-1532-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knight L, Mukumbang FC, Schatz E. Behavioral and cognitive interventions to improve treatment adherence and access to HIV care among older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: an updated systematic review. Syst Rev 2018;7:114. 10.1186/s13643-018-0759-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kredo T, Adeniyi FB, Bateganya M, et al. . Task shifting from doctors to non-doctors for initiation and maintenance of antiretroviral therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;17:CD007331. 10.1002/14651858.CD007331.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kredo T, Ford N, Adeniyi FB, et al. . Decentralising HIV treatment in lower- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;17:CD009987. 10.1002/14651858.CD009987.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lima ICVde, Galvão MTG, Alexandre HdeO, et al. . Information and communication technologies for adherence to antiretroviral treatment in adults with HIV/AIDS. Int J Med Inform 2016;92:54-61–61. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma PHX, Chan ZCY, Loke AY. Self-Stigma reduction interventions for people living with HIV/AIDS and their families: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2019;23:707–41. 10.1007/s10461-018-2304-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.MacPherson P, Munthali C, Ferguson J, et al. . Service delivery interventions to improve adolescents' linkage, retention and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV care. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1015–32. 10.1111/tmi.12517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manias E, Williams A. Medication adherence in people of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:964–82. 10.1345/aph.1M572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine S-L, et al. . Adherence-enhancing interventions for highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients - a systematic review. HIV Med 2013;14:583–95. 10.1111/hiv.12051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mavegam BO, Pharr JR, Cruz P, et al. . Effective interventions to improve young adults' linkage to HIV care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Care 2017;29:1198–204. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1306637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mayer JE, Fontelo P. Meta-Analysis on the effect of text message reminders for HIV-related compliance. AIDS Care 2017;29:409–17. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1214674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mbeye NM, Adetokunboh O, Negussie E, et al. . Shifting tasks from pharmacy to non-pharmacy personnel for providing antiretroviral therapy to people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015072. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mbuagbaw L, Sivaramalingam B, Navarro T, et al. . Interventions for enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy (art): a systematic review of high quality studies. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:248–66. 10.1089/apc.2014.0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mbuagbaw L, Ye C, Thabane L. Motivational interviewing for improving outcomes in youth living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD009748. 10.1002/14651858.CD009748.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Medley A, Bachanas P, Grillo M, et al. . Integrating prevention interventions for people living with HIV into care and treatment programs: a systematic review of the evidence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68 Suppl 3:S286-96–96. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mills EJ, Lester R, Thorlund K, et al. . Interventions to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a network meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 2014;1:e104–11. 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00003-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mizuno Y, Higa DH, Leighton CA, et al. . Is HIV patient navigation associated with HIV care continuum outcomes? AIDS 2018;32:2557–71. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Muessig KE, Nekkanti M, Bauermeister J, et al. . A systematic review of recent smartphone, Internet and web 2.0 interventions to address the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:173–90. 10.1007/s11904-014-0239-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Murray KR, Dulli LS, Ridgeway K, et al. . Improving retention in HIV care among adolescents and adults in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Musayón-Oblitas Y, Cárcamo C, Gimbel S. Counseling for improving adherence to antiretroviral treatment: a systematic review. AIDS Care 2019;31:4–13. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mutasa-Apollo T, Ford N, Wiens M, et al. . Effect of frequency of clinic visits and medication pick-up on antiretroviral treatment outcomes: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21647. 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nachega JB, Adetokunboh O, Uthman OA, et al. . Community-Based interventions to improve and sustain antiretroviral therapy adherence, retention in HIV care and clinical outcomes in low- and middle-income countries for achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13:241–55. 10.1007/s11904-016-0325-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parienti Jean‐Jacques, Bangsberg DR, Verdon R, et al. . Better adherence with Once‐Daily antiretroviral regimens: a Meta‐Analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Park LG, Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. A quantitative systematic review of the efficacy of mobile phone interventions to improve medication adherence. J Adv Nurs 2014;70:1932–53. 10.1111/jan.12400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Perazzo J, Reyes D, Webel A. A systematic review of health literacy interventions for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2017;21:812–21. 10.1007/s10461-016-1329-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Purnomo J, Coote K, Mao L, et al. . Using eHealth to engage and retain priority populations in the HIV treatment and care cascade in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:82. 10.1186/s12879-018-2972-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Quintana Y, Gonzalez Martorell EA, Fahy D, et al. . A systematic review on promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients using mobile phone technology. Appl Clin Inform 2018;9:450-466–66. 10.1055/s-0038-1660516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ramjan R, Calmy A, Vitoria M, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis: patient and programme impact of fixed-dose combination antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:501–13. 10.1111/tmi.12297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ridgeway K, Dulli LS, Murray KR, et al. . Interventions to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189770. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Riley KE, Kalichman S. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people living with HIV/AIDS: preliminary review of intervention trial methodologies and findings. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9:224–43. 10.1080/17437199.2014.895928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Risher KA, Kapoor S, Daramola AM, et al. . Challenges in the evaluation of interventions to improve engagement along the HIV care continuum in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2101–23. 10.1007/s10461-017-1687-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Robbins RN, Spector AY, Mellins CA, et al. . Optimizing art adherence: update for HIV treatment and prevention. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014;11:423–33. 10.1007/s11904-014-0229-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rocha BS, Silveira MPT, Moraes CG, et al. . Pharmaceutical interventions in antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Pharm Ther 2015;40:251–8. 10.1111/jcpt.12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi A, et al. . Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;18 10.1002/14651858.CD001442.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruzagira E, Baisley K, Kamali A, et al. . Linkage to HIV care after home-based HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:807–21. 10.1111/tmi.12888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saberi P, Dong BJ, Johnson MO, et al. . The impact of HIV clinical pharmacists on HIV treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012;6:297–322. 10.2147/PPA.S30244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Saberi P, Johnson MO. Technology-Based self-care methods of improving antiretroviral adherence: a systematic review. PLoS One 2011;6:e27533. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey KB, Johnson BT, et al. . Behavioral interventions targeting alcohol use among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 2017;21:126–43. 10.1007/s10461-017-1886-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sharma M. Evaluating the efficiency of community-based HIV testing and counseling strategies to decrease HIV burden in sub-Saharan Africa. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2017;78. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shaw S, Amico KR. Antiretroviral therapy adherence enhancing interventions for adolescents and young adults 13–24 years of age. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2016;72:387–99. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Suthar AB, Nagata JM, Nsanzimana S, et al. . Performance-Based financing for improving HIV/AIDS service delivery: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:6. 10.1186/s12913-016-1962-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Swann M. Economic strengthening for retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care 2018;30:99–125. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1479030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tang AM, Quick T, Chung M, et al. . Nutrition assessment, counseling, and support interventions to improve health-related outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review of the literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68 Suppl 3:S340–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Van Camp YP, Van Rompaey B, Elseviers MM. Nurse-Led interventions to enhance adherence to chronic medication: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:761–70. 10.1007/s00228-012-1419-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.van der Heijden I, Abrahams N, Sinclair D, et al. . Psychosocial group interventions to improve psychological well-being in adults living with HIV. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017;68 10.1002/14651858.CD010806.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.van Velthoven MHMMT, Brusamento S, Majeed A, et al. . Scope and effectiveness of mobile phone messaging for HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review. Psychol Health Med 2013;18:182-202–202. 10.1080/13548506.2012.701310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.van Velthoven MHMMT, Tudor Car L, Car J, et al. . Telephone consultation for improving health of people living with or at risk of HIV: a systematic review. PLoS One 2012;7:e36105. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vervloet M, Linn AJ, van Weert JCM, et al. . The effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012;19:696–704. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vojnov L, Markby J, Boeke C, et al. . Poc CD4 testing improves linkage to HIV care and timeliness of art initiation in a public health approach: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155256 10.1371/journal.pone.0155256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wise J, Operario D. Use of electronic reminder devices to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008;22:495–504. 10.1089/apc.2007.0180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wouters E, Van Damme W, van Rensburg D, et al. . Impact of community-based support services on antiretroviral treatment programme delivery and outcomes in resource-limited countries: a synthetic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:194. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wynberg E, Cooke G, Shroufi A, et al. . Impact of point-of-care CD4 testing on linkage to HIV care: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17:18809. 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Yang Y. State of the science: the efficacy of a multicomponent intervention for art adherence among people living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2014;25:297–308. 10.1016/j.jana.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Young T, Busgeeth K. Home-Based care for reducing morbidity and mortality in people infected with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;13:CD005417. 10.1002/14651858.CD005417.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ng M, Gakidou E, Levin-Rector A, et al. . Assessment of population-level effect of Avahan, an HIV-prevention initiative in India. The Lancet 2011;378:1643–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Haberer JE, Sabin L, Amico KR, et al. . Improving antiretroviral therapy adherence in resource-limited settings at scale: a discussion of interventions and recommendations. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:21371. 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.World Health Organization Progress report 2016: prevent HIV test and treat all: who support for country impact: World Health organization 2016.

- 132.Geng EH, Odeny TA, Lyamuya R, et al. . Retention in care and patient-reported reasons for undocumented transfer or stopping care among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in eastern Africa: application of a sampling-based approach. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:935–44. 10.1093/cid/civ1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. . Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61:574-80–80. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318273762f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034793supp001.pdf (84.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-034793supp002.pdf (250.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-034793supp003.pdf (163.6KB, pdf)