Abstract

Emotional schemas are pervasive mental structures associated with a wide array of psychological symptoms, while mindfulness, self-compassion, and self-acceptance are viewed as adaptive psychological constructs. Psychological needs may be described as the cornerstone of mental health and well-being. However, a study of the relationships between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, and self-acceptance with psychological needs was not performed. For this purpose, 250 subjects (M=20.67, SD=4.88, Male=33, Female=217), were evaluated through self-report questionnaires, in a cross-sectional design. Negative correlations were found between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, unconditional self-acceptance, and psychological needs. Symptomatology was positively correlated with emotional schemas. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and unconditional self-acceptance predicted the regulation of psychological needs and mediated the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs. Emotional schemas may be associated with a tendency for experiential avoidance of internal reality, self-rejection/shame and self-criticism which may impair the regulation of psychological needs. These variables may be targets of integrative case conceptualization and clinical decision making focused on patient’s timings, styles of communication and needs.

Key words: Emotional schemas, Self-compassion, Unconditional Self-acceptance, Mindfulness, Psychological Needs

Introduction

Schematic Functioning and Emotional Schemas

The schematic conceptualization of emotional experience has gained increasing relevance in disorder theories across different theoretical orientations (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; Greenberg, 2015; Leahy, 2015; Vasco, 2013; Vasco, Conceição, Silva, Ferreira, & Vaz-Velho, 2018). This may concern to the fact that emotions play a central role in human life, therefore, they are a core object of theorization and clinical intervention in psychotherapy (Elliott, Watson, Goldman, & Greenberg, 2004). However, some theoretical unification regarding the conceptualization of emotion constructs seems to be missing, because, different theoretical orientations may emphasize different aspects of emotions or emotional experiences. In spite of these concerns one major factor that seems to have a central role in a wide array of psychological disorders, beyond different orientations is the emotional suffering that steams out from painful emotional experience (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Greenberg, 2015; Leahy, 2015; Vasco, 2013; Vasco et al., 2018; Young, Klosko & Weishaar, 2003).

Along with this, negative beliefs, interpretations, expectations, and dysfunctional meaning-making processes seem to be recurring elements across different theories, which supports the notion of maladaptive cognitive appraisals and emotion regulation strategies (Greenberg, 2015; Gross 2002; Leahy, 2015; Vasco et al., 2018). The notion of recurring elements of experience may be referred to as schemas or schematic functioning (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003). Thus, schematic functioning describes the functions of a schema or schema operations along diverse steps in cognitive and affective information processing (Leahy, 2015; Greenberg, 2015).

Faustino and Vasco (2020a; 2020c) described some possible definitions of schemas (e.g. early maladaptive schemas, emotional schemas, self-wounds), showing the diversity of this concept. However, this diversity may raise some theoretical and clinical implications, especially in a consensus of what are the structure of schemas and how to work with them. This question remains unanswered and we will try to address this issue in the future. Nevertheless, along with these definitions, one stands out to be a perfect match to capture the emotional experience across different theories, which is the notion of an emotional schema (Greenberg, 2015; Leahy, 2015; Vasco, 2013; Vasco et al., 2018).

In Emotion-Focused Therapy approach (EFT; Pascual- Leone & Greenberg, 1997; Greenberg, 2015) emotion schemes are organizing structures that attach meaning to the emotional experience which supports emotional schematic processing. With other words, emotion schemes are basic internal scrips that articulate different mental elements that assign cognitive content to affective states giving rise to a highly integrated conscious experience (Greenberg, 2015). Emotion schemes have highly articulated physiological, cognitive, episodic memory and motor-expressive compounds that organize and potentially reorganize along life cycle in response to life experiences (Pascual-Leone & Greenberg, 2007; Greenberg, 2015; Vasco, 2013).

In EFT model, emotions play a central role in mental health and well-being because of the implications that expression, validation, self-understanding, clarification, and recognition of emotions have in the adaptive emotional experience (Pascual-Leone & Greenberg, 2007). Despite other affective phenomena Vasco (2013) expands the functionality of the emotions and their relationship with psychological needs. Emotions have several functions, such as guidance, communication, preventive and a signalizing function which informs the degree of regulation of psychological needs being the cornerstone in adaptation theory of Paradigmatic Complementarity Metamodel (PCM, Vasco, 2001; 2005; Vasco et al., 2018).

In Cognitive Behavior Therapy tradition (CBT; Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Leahy, 2015) emotional experience may have a different approach. Leahy (2002) has a socio-cognitive perspective of emotional phenomena and defines emotional schemas as specific beliefs and dysfunctional strategies that individuals use to deal with emotional experiences. The author refers that emotions may be the target for psychological intervention being this an expansion to traditional CBT view, typically focused on dysfunctional beliefs, attitudes and behaviors about the self, others and the world (Leahy, 2015). In Emotional Schema Therapy (EST, Leahy, 2002, 2015), there are fourteen dimensions of emotional schemas, divided in beliefs about emotions (e.g., duration, acceptance, comprehensibility) and coping strategies (e.g., rationality, control).

Previous research had associated emotional schemas with anxiety, depression, alexithymia, trauma, and difficulties in the socialization processes (Leahy, 2011; Leahy et al., 2018; Edwards, Micek, Monttarella, & Wupperman, 2016; Edwards & Wupperman, 2018; Palmeira, Pinto-Gouveia, Dinis, & Lourenço, 2011). Leahy (2007) also emphasizes the transdiagnostic feature of emotions in the various disorders of the spectrum of anxiety and links it to the emotional regulation coping strategies. Faustino (2020), emphasized the transdiagnostic feature of emotion dysregulation domains and psychological inflexibility associated with emotion regulation strategies. Thus, emotion regulation is also associated with emotional schemas (Leahy, 2018) and psychological needs (Castelo-Branco, 2016). Silberstein, Tirch, Leahy and McGinn, (2012) showed the positive and negative associations between mindfulness, psychological flexibility, and emotional schemas. The authors showed that higher levels of mindfulness and psychological flexibility were associated with less dysfunctional beliefs and coping strategies (emotional schemas). However, despite these findings, it is not clear if the same relationships could be found within other psychological constructs as self-compassion or unconditional selfacceptance and what role they play on the regulation of psychological needs.

Mindfulness, Self-Acceptance, and Self-Compassion

Third-generation CBT emphasize the role of mindfulness, self-compassion, and self-acceptance in promoting psychological flexibility, smoothing self-criticism, and accepting painful private experience (Gilbert, 2010; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2011; Liehnan, 1993; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2013). In the past twenty years, these were some of the most researched topics leading to the increase awareness of these constructs as possible mechanisms of change (Hayes et al., 2011). Interestingly, as we will see these constructs share some similarities.

Mindfulness may be defined as the ability to focus and maintain attention to internal and external experience, with an accepting and non-judgmentally attitude (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). It involves a higher awareness of internal moment-to-moment states and relate them to thoughts and emotions in a decentered manner as mental events rather than than accurate reflections of the self and reality (Segal et al., 2013; Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Mindfulness- Based Interventions (MBIs) as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1982) and Mindfulness- Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., 2013), found empirical support in a meta-analytic review, where positive effects were found in a range of outcomes in clinical and nonclinical samples including stress, depression, depressive relapse, and anxiety (e.g., Chiesa & Serretti, 2009; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010; Piet & Hougaard, 2011; Strauss, Cavanagh, Oliver, & Pettman, 2014). Thus, mindfulness-based interventions hold to some degree evidence of effectiveness in depression, pain conditions, smoking, and addictive disorders (Golderg et al., 2018).

Unconditional self-acceptance or self-acceptance has a long history in CBT literature from Rational Emotional Therapy (REBT; Ellis, 1994) to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2011). In REBT literature, unconditional self-acceptance is described as a tendency to evaluate self-worth or ability to fully accept his/herself, regardless of the outcome (Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001). In ACT literature, self-acceptance is described as the ability to be in contact with internal private experience to process it (assimilate and accommodate it in self-knowledge). These two definitions imply that an individual may have some facets of the self that may be painful, unwanted or socially inadequate, and he/she may try to avoid them in order to maintain psychological stability. Thus, experiential avoidance is associated with cognitive fusion which are core concetps on the ACT psychopathology model (Hayes et al., 2011).

In REBT tradition, previous research had associated positively self-acceptance to mental health, and higher levels of life satisfaction (Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001). On the other hand self-acceptance had been negatively associated with anxiety and depression symptomatology and low self-steem (Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001). Also, unconditional self-acceptance showed to be a significant predictor of depression (Popov, Biro & Radanović, 2016). Thus, in a recent study Popov (2019), showed that unconditional self-acceptance was a significant predictor of depression, anxiety, and low levels with life satisfaction. In ACT tradition, self-acceptance and cognitive defusion tend be viewed as the counterpart of experiential avoidance and cognitive fusion which tend to be associated with anxiety, depression and psychological distress (Gilanders et al., 2014; Bardeen & Fergus, 2016), early maladaptive schemas and interpersonal dysfunctional cycles (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; 2020b) and emotional dysregulation (Faustino, 2020). The ACT definition of self-acceptance overlaps with previous mindfulness definition. In this sense, our study focused our attention on REBT definition, of unconditional self-acceptance because it represents a self-appraisal.

Self-compassion may be defined as a warming/kind attitude in the acceptance of self-negative aspects and may involve three aspects: i) warm/comprehension towards the self in spite of being self-punitive and critical, ii) understand self-experiences as a larger experience of human condition and iii) a mindfulness conscious with acceptance of own feeling beyond action (Neff, 2003). Gilbert (2005), understand compassion through an evolutionary psychological perspective of social mentalities and attachment theory. The author state that capacity for compassion relates to motivational competencies (related to the desire to take care of the other); emotional (related with the capacity to detect discomfort), behavioral (related to the ability to tolerate discomfort instead of avoiding it) and cognitive (related to ability to understand the source of the discomfort and what is needed to help who is disturbed) (Gilbert, 2005).

Despite these two definitions, research on self-compassion showed on one hand, that it is positively associated with happiness, social connectivity, wisdom, optimism, personal initiative, curiosity, extroversion, pleasantness, exploration, conscientiousness and affectivity (Neff, Hseih, & Dejitthirat, 2005), and negatively associated with depressive symptomatology, anxiety, self-criticism and affectivity negative (Neff et al., 2005). Thus, in a meta-analysis conducted by Macbeth and Gumley (2012), some associations between self-compassion and psychopathology were described where, self-compassion showed to be negatively correlated with anxiety and depressive symptoms (Costa & Pinto-Gouveia, 2011; Raes, 2011; Gilbert, McEwan, Matos, & Rivis, 2011), and stress symptoms (Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010; Raque-Bogdan, Ericson, Jackson, Martin, & Bryan, 2011). In this sense, self-compassion seems to be a relevant variable to be target of psychological intervention (Gilbert et al., 2011).

Moreover, there is some overlap between these three concepts, where mindfulness can be a condition for an individual understands and accepts the internal experience without acting, judging or using coping strategies to avoid, module or change it to process and integrate it within the self. However, to do this, the individual needs to have a mental stance of self-compassion that allows and facilitates acceptance of internal experience. Despite these overlaps, there is a gap in the literature of the study of the relationship between emotional schemas and these adaptive mental stances, namely mindfulness, self-compassion, and unconditional self-acceptance, and how they relate to psychological needs. Thus, Thim (2017), showed that self-compassion and mindfulness are positively associated and negatively associated early maladaptive schemas. However, this relationship was not tested with emotional schemas and with the regulation of psychological needs.

Regulation of the Psychological Needs

According to Vasco et al., (2018) the regulation of psychological needs is the cornerstone of mental health and well-being and is a core construct in the PCM (Conceição & Vasco, 2005; Vasco, 2013; Vasco et al., 2018). PCM is an integrative model that allows an incorporation of diverse theoretical and empirical views of clinical phenomenon that may be useful for case conceptualization and clinical decision making. Psychological needs are states of disequilibrium caused by a lack or excess of certain psychological nutrients that are signaled emotionally and when working adequately, promote inner and outer action tendencies leading to the establishment of a new mental balance (Vasco et al., 2018). Thus, it is the emotional system that informs the degree of regulation of psychological needs which means that individuals need to attend and understand their emotions to be able to restore inner balance (Vasco et al., 2018).

Previous research showed that the regulation of psychological needs is negatively associated with core dysfunctional variables from diverse theoretical orientations, such as, early maladaptive schemas and cognitive fusion (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; 2020b; Fonseca, 2012), emotional processing difficulties (Faustino et al., 2019; Faustino & Vasco, 2020c; Barreira, 2016), interpersonal dysfunctional cycles and defensive styles (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; Martins, 2016) and emotion regulation difficulties (Castelo-Branco, 2016). In line with these evidences, the schematic functioning seems to be closely associated with difficulties on the regulation of psychological needs. Through a mixed regression analysis Faustino and Vasco, (2020a) showed that the schematic domain of disconnection and rejection with three domains of dysfunctional interpersonal cycles of selfcare/ integrity, internalization/ self-punishment, and response to the object/reactive formation predicted the variance of the regulation of psychological needs. Faustino and Vasco, (2020b) described two mediation models where cognitive fusion was a significant mediator of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and the regulation of psychological needs. Finally, Faustino and Vasco (2020c) found that three schema domains of disconnection and rejection, impaired autonomy, and impaired limits were significant mediators of the relationship emotional processing difficulties and the regulation of psychological needs.

Furthermore, the regulation of psychological needs showed to be negatively correlated with symptomatology and psychological distress, and showed to be positively correlated with psychological well-being (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; Barreira, 2016; Castelo-Branco, 2016; Conde, 2012; Martins, 2016; Sol & Vasco, 2017). These results imply a strict relationship between these constructs and specially between schematic functioning and the regulation of psychological needs. However, the relationship between emotional schemas, between mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and the regulation of psychological needs has never been tested. This research aims to fill this gap. Thus, it is intended to study the relationships between the above-mentioned variables in a transtheoretical, complementary and integrative approach.

Research Issues and Hypothesis

According to the previous theorization, it is possible to unfold an integrative model. The regulation of psychological needs is a core aspect in mental health which tend to be impaired by the presence of early maladaptive schemas, dysfunctional cycles, emotional processing difficulties, cognitive fusion and defensive styles (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; 2020b, 2020c; Barreira, 2016; Castelo- Branco, 2016; Fonseca, 2012; Martins, 2016). Emotional schemas are dysfunctional beliefs and coping strategies to deal with emotional experiences, which may result in difficulties on the regulation of psychological needs, which in turn may promote symptomatology. Emotional schemas may be conceptualized as dysfunctional structures of the schematic functioning which may impair the emotional system responsible for signaling the degree of the frustration of the psychological needs. However, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion may be viewed as adaptive trait or state self-instances that may moderate emotional schemas and facilitate the regulation of psychological needs.

Within this integrative framework we raise the following research issues and hypothesis: Emotional schemas are negatively associated with unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness (Hypothesis 1); Emotional schemas are positively associated with symptomatology (Hypothesis 2); Emotional schemas are negatively associated with psychological needs (Hypothesis 3); Unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness predicts emotional schemas (Hypothesis 4); Emotional schemas, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness predicts symptomatology (Hypothesis 5); Emotional schemas, unconditional self-acceptance, selfcompassion, and mindfulness predicts psychological needs (Hypothesis 6); Unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness are significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology in isolation and in interaction (Hypothesis 7); Unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness are significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs in isolation and in interaction (Hypothesis 8).

Materials and Methods

Inclusion Criteria and Participants

The sample consisted of 250 undergraduate Portuguese students of the course of psychological sciences of the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon, living in the municipality of Lisbon, with 33 males (13.4%) and 217 females (86.6%), with a mean age of 20.67 years (SD = 4.88). Inclusion criteria were being over 18 years old, speaking Portuguese as a native language and not having a neurocognitive disorder (see Table 1).

Leahy Emotional Schemas Scale-50 (LESS-50)

To evaluate emotional schemas the LESS- 50 (Leahy et al., 2012; Portuguese version by da Silva, Matos, Faustino & Dias Neto, 2019),), was used. LESS - 50 is a self-report measure with 50 items and 6-point Likert scale, from 1 to 6, aimed to assess fourteen dimensions of emotional schema dimensions. In the present study, only the general index was used. Cronbach alfa was good (α = 0.888).

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ, Baer., et al, 2006, Portuguese version made by Pinto Gouveia, & Gregório, 2007), is a self-report measure with 39 items on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5, aiming to assess five domains of mindfulness. In the present study, only the general index was used. Cronbach alfa was medium (α = 0.653).

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

Self-Compassion was assessed with the SCS (Neff, 2003; Portuguese version by Castilho, Pinto-Gouveia, & Duarte, 2015). SCS is a self-report measure with 26 items on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5, aiming to assess self-compassion. In the present study, only the general index was used. Cronbach alfa was medium (α = 0.691).

Unconditional Self-Acceptance Questionnaire (USAQ)

Unconditional Self-Acceptance Questionnaire (USAQ, Chamberlain & Haaga, 2001, is a self-report measure with 20 items on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 to 7, aiming to assess unconditional self-acceptance. Cronbach alfa was medium (α = 0.552).

Needs Satisfaction Regulation Scale (NSRS-43)

The psychological needs were assed using the NSRS- 43 (Conde, 2012). NSRD-43 is a self-report measure with 14 subscales referring to fourteen psychological needs. In the present study, only the general index was used. The response format is an 8-point Likert scale. Internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.902).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the sample.

| N | 250 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| M | 20.67 | |

| SD | 488.00% | |

| Mínimum | 1800.00% | |

| Máxium | 5700.00% | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 33 (13.4%) | |

| Female | 217 (86.6%) | |

| Years of Education | ||

| 12º year | 227 (90.8%) | |

| Bachelor | 18 (7.2%) | |

| Master | 5 (2.0%) | |

| Years of Education | ||

| Single | 238 (95.2%) | |

| Married | 8 (3.2%) | |

| Fact Union | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Divorced | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Years of Education | ||

| Yes | 46 (18.4%) | |

| No | 204 (81.6%) |

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

Symptomatology was assessed through BSI (Derogatis 1993; Portuguese version by Canavarro, 1999). BSI is a self-report inventory composed of 53 items on a 5- point Likert scale response (0 = never to 4 = many times) focused on the assessment psychopathological symptoms. Internal consistency was considered excellent (α= 0.967).

Procedure and Data Analysis

All participants were undergraduate students at the Faculty of Psychology of University of Lisbon, having completed the self-report questionnaires in the Qualtrics online platform. Informed consent and confidentiality were given to all participants. Socioeconomic status was considered equivalent. This research was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Psychology of University of Lisbon. This study had a cross-sectional design within a quantitative approach. To explore sample features descriptive statistics were used. Multicollinearity values showed to be adequate |VIF < 2; T < 7|, normal distribution was assumed (N > 30) and a 95% confidence interval was assumed with p-value of 0.05 (Pallant, 2007). Person correlations were used to study the degree of association between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, unconditional self-acceptance, and symptomatology. Next, a stepwise multiple regression was used to find the best predictors of the variance of emotional schemas and symptomatology. A mediation analysis between emotional schemas and symptomatology was performed with mindfulness, selfcompassion, and unconditional self-acceptance proposed as significant mediators (Hayes, 2013).

Finally, this work belongs to a wider line of research seeded in translational science where it is intended to use clinical psychology and integrative psychotherapy, neuropsychology, and neuroscience methods to (1) identify and understand relationship between core clinical variables, (2) to deepen it’s understanding, (3) to emphasize points of contact between sciences and (4) to inform case conceptualization and clinical decision making.

Results

Correlational Analysis

Through Person´s correlations, we identified the associations between emotional schemas, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, psychological needs and symptomatology (Hypothesis 1, 2 and 3). Emotional schemas had strong negative correlations with, psychological needs, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion and medium negative correlation with mindfulness. Emotional schemas had a strong positive correlation with symptomatology. Psychological needs are strongly positively correlated with mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance and self-compassion – see Table 2.

Table 3 shows correlations between symptomatic domains and between emotional schemas, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness. Medium to strong negative correlations were found between emotional schemas and all symptomatic domains (p.<0.05). Also, weak to strong negative correlations were found between all symptomatic domains and unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion and mindfulness (p.<0.05; see Table 3).

Stepwise Regression Analysis

Through multiple stepwise regression analysis was used to find the best predictors of emotional schemas (hypothesis 4), symptomatology (hypothesis 5) and psychological needs (hypothesis 6). An integrative model was found with three predictors that explain 47% of the variance of emotional schemas (R2 = 0.470, F = 72,663, p. < .001). Regarding symptomatology as dependent variable, an integrative model with two predictors was found, with emotional schemas and self-compassion explain 43.2 % of variance (R2 = .432, F = 93,782, p. < .00). Regarding psychological needs as dependent variable, an integrative model with three predictors was found, explain 66% of variance (R2 = .611, F = 128,784, p. < .00; see Table 4).

Mediation Analysis

On mediation analysis we tested first the variables in isolation (unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness), then we tested composite mediations with these three variables, first on the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology (hypothesis 7) and then on the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs (hypothesis 8). We tested mediations with Process SPSS AAD (Hayes, 2013), and a 10,000 number of bootstrap computations with 95% confidence intervals were used. It was found that unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness in isolation were statistically significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology (p.<0.001; see Table 5).

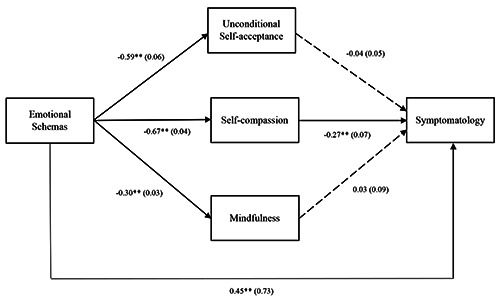

We tested a composite model with the three variables as mediators. However, only self-compassion |.07, .30| was a significant mediator of the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology (b = .45, p. <.001; see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Correlations between emotional schemas, psychological needs, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and symptomatology (N= 250).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional schemas | 1 | -0.680** | -0.483** | -0.511** | -0.652** | 0.620** |

| Psychological needs | -0.680** | 1 | 0.588** | 0.535** | 0.692** | -0.596** |

| Mindfulness | -0.483** | 0.588** | 1 | 0.401** | 0.522** | -0.347** |

| Self-acceptance | -0.511** | 0.535** | 0.401** | 100.00% | 0.599** | -0.420** |

| Self-compassion | -0.652** | 0.692** | .0522** | 0.599** | 1 | -0.568** |

| Symptomatology | 0.620** | -0.596** | -0.347** | -0.420** | -0.568** | 100.00% |

**p.< 0.05; Emotional schemas = 1; Psychological needs = 2; Mindfulness = 3; Self-acceptance = 4; Self-compassion = 5; Symptomatology = 6.

Table 3.

Correlations between symptomatic domains and between emotional schemas, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion (n=250).

| Emotional schemas | Mindfulness | Self-acceptance | Self-compassion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatization | 0.434** | -0.209** | -0.230** | -0.431** |

| Obssessive-compulsive | 0.534** | -0.297** | -0.327** | -0.498** |

| Interpersonal sensivity | 0.564** | -.343** | -0.462** | -0.534** |

| Depression | 0.601** | -0.406** | -0.452** | -0.579** |

| Anxiety | 0.508** | -0.258** | -0.316** | -0.482** |

| Hostility | 0.481** | -0.257** | -0.376** | -0.447** |

| Fobic anxiety | 0.349** | -0.132** | -0.203** | -0.304** |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.490** | -0.217** | -0.332** | -0.396** |

| Psicoticism | 0.657** | -0.435** | -0.447** | -0.543** |

**p.< 0.05.

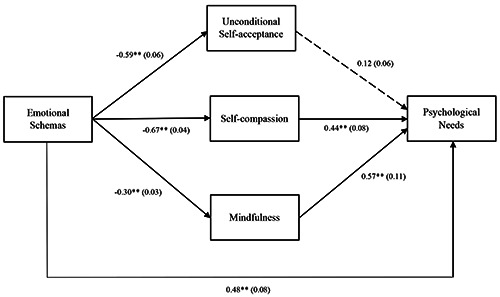

Then, we tested if mindfulness, unconditional selfacceptance, and self-compassion in isolation were significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs (Hypothesis 8). It was found that unconditional self-acceptance, self-compassion, and mindfulness in isolation were statistically significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology (p.<0.001; see Table 5). It was found that self-compassion |-0.45, -0.15| and mindfulness |-0.17, -0.25| were statistically significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs (b = -0.48, p. <0.001; see Figure 2.

Discussion

The aim of this research was achieved. We explored the relationships between emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, and unconditional self-acceptance, along with its relationship psychological needs with symptomatology. Emotional schemas may impair the regulation of psychological needs and mindfulness, self-compassion, and unconditional self-acceptance may contribute to schema weakening.

Correlational analysis gave support to the hypothesis where emotional schemas were negatively associated with mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion (confirmation of hypothesis 1). These results may be aligned with previous works, where in a correlational study individuals with higher dispositional mindfulness and higher psychological flexibility were more likely to report fewer rigid responses to emotional experience (Silberstein, et al., 2012). Westphal, Leahy, Pala, and Wupperman (2016), showed that self-compassion was negatively associated with emotional invalidation. One possible explanation may be that individuals with emotional schemas are less prone to internal openness, are more rigid in their beliefs and strategies and are less capable of being compassionate due to psychological inflexibility.

This is also true to the association with emotional schemas and psychological needs. One likely explanation may be that individuals with dysfunctional beliefs and strategies may have difficulties on the understanding of emotional experience which in turn, may impair the emotional system functioning. Thus, it is the emotional system that signals the degree of under-regulaton or over-regulation of the psychological needs (Faustino & Vasco, 2020c; Vasco et al., 2018; Vasco, 2013). In this sense, individuals with emotional schemas may not have the ability to identify and differentiate their emotions which impair the regulation of the psychological needs. Another explanation may be that individuals with emotional schemas may have difficulties to move back and forth on the polarities of psychological needs which compromised its regulation (Conceição & Vasco, 2005; Vasco et al., 2018). This may be due to the structural inflexibility that the schematic functioning implies (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a).

Table 4.

Stepwise multiple regressions analysis with emotional schemas, symptomatology, and psychological needs as the dependent variables (n=250).

| R2 | B | St. error | Beta | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Schemas | ||||||

| Self-compassion | 0.425 | -0.448 | 0.061 | -46.20% | -7.364 | 0 |

| Mindfulness | 0.453 | -0.281 | 0.088 | -17.60% | -3.206 | 0.002 |

| Self-acceptance | 0.47 | -13.90% | 0.05 | -16.30% | -2.793 | 0.60% |

| Symptomatology | ||||||

| Emotional schemas | 0.385 | 46.20% | 0.067 | 43.50% | 6.873 | 0.00% |

| Self-compassion | 0.432 | -29.30% | 0.065 | -28.50% | -4.501 | 0.00% |

| Psychological Needs | ||||||

| Self-compassion | 0.478 | 51.00% | 0.082 | 34.40% | 6.224 | 0.00% |

| Emotional schemas | 0.569 | -51.70% | 0.082 | -33.70% | -6.273 | 0.00% |

| Mindfulness | 0.611 | 0.599 | 0.117 | 0.245 | 5.129 | 0.000 |

Table 5.

Mediation analysis emotional schemas, symptomatology and psychological needs with mindfulness, unconditional selfacceptance, and self-compassion as mediators in isolation (N=250).

| Emotional Schemas and Symptomatology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta* | SE | Lower-Limit | Upper-Limit | Sig | |

| Mindfulness | 0.0514 | 0.0188 | 0.0167 | 9.10% | 0 |

| Self-acceptance | 0.0487 | 0.0247 | 0.0021 | 9.93% | 0 |

| Self-compassion | 0.1612 | 38.30% | 0.0902 | 24.22% | 0 |

| Emotional Schemas and Psychological Needs | |||||

| Beta* | SE | Lower-Limit | Upper-Limit | Sig | |

| Mindfulness | -0.2503 | 4.33% | -0.3379 | -16.76% | 0 |

| Self-acceptance | -0.1985 | 4.73% | -0.296 | -10.82% | 0 |

| Self-compassion | -0.4317 | 7.75% | -0.5921 | -29.11% | 0 |

*Indirect effects are showed.

Emotional schemas where associated with symptomatology as expected (confirmation of hypothesis 2). In fact, there is enough literature to support the association between schematic functioning, emotional schemas, and symptomatology (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; Edwards et al. 2016, Edwards & Wupperman, 2018; Leahy, 2011; Leahy et al., 2018). Thus, this may also imply that emotional schemas may be another compound of the dysfunctional schematic functioning underlying all psychological disorders. The centrality of emotional suffering is well documented in the literature (Conceição & Vasco, 2005; Ellitot, et al., 2004; Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Greenberg, 2015; Gross 2002; Leahy et al., 2018; Liehnan, 1993; Vasco et al., 2018). However, the research of the centrality of the emotional schemas in psychological disorders is still underway. Nonetheless, more research is required to support the notion that emotional schemas underly all psychological disorders.

Figure 1.

Mediation analysis between emotional schemas and psychological needs with mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion as mediators (b = 0.20, p. <0.05).

Figure 2.

Mediation analysis between emotional schemas and psychological needs with mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion as mediators (b = -0.55, p. <0.05).

Findings showed that the regulation of psychological needs are positively associated with mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion, being this a new evidence (confirmation of hypothesis 3). We view psychological needs as the cornerstone of mental health as previous research has shown (Faustino & Vasco, 2020a; 2020b; 2020c; Barreira, 2016; Castelo-Branco, 2016; Fonseca, 2012; Martins, 2016; Sol & Vasco, 2017; Vasco et al., 2018). We could argue that mindfulness, selfunconditional acceptance, and self-compassion may be different aspects of the self and they may reflect and adaptive regulation of psychological needs through different mechanisms. Thus, we can see mindfulness and unconditional self-acceptance as different traits or states that express adaptive abilities (in case of unconditional self-acceptance an adaptive self-appraisal) and self-compassion as attitude or a mentality towards the self. First, individuals who can be mindful may be more able to be in touch with emotions and emotional experience which may facilitate emotional awareness, being this a key feature to the regulation of the psychological needs. Second, individuals who are able to accept themselves as they are without the outcomes of their behavior may be more open to understand, validate and value themselves as human beings with flaws and virtues. In this sense, individuals may be more able to validate their emotions and their needs even if they are contradictory (Vasco et al., 2018). Third, individuals who are self-compassionate may soothe internal criticism and pessimism more easily, which in turn may reduce emotional suffering and promote the regulation of psychological needs. Therefore, these three variables may represent these three distinct mechanisms with protective or adaptive effects on psychological functioning.

This leads to the notion that when psychological needs are regulated, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance and self-compassion are strongly associated and they may be a protective factor which could help to understand it´s predictive value in emotional schemas (confirmation of hypothesis 4). Thus, Thim (2017) showed that mindfulness and self-compassion are positively associated within themselves and they moderate the relationship between maladaptive schemas and symptoms. In this sense, our work may help to understand that emotional schemas may also be predicted with other variables such as the lack of unconditional self-acceptance.

We expected that the variance of symptomatology would be best explained by a full integrative hierarchical model with emotional schemas, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion. However, only a model with two predictors (emotional schemas and self-compassion) was found (non-confirmation of hypothesis 5). This results is partialy in line with previous work done by Tirch, Leahy, Silberstein and Melwani (2012). The authors described a multiple regression analysis where with emotional schemas (control and duration) and psychological flexibility were the best predictors of anxiety and symptomatology. Moreover, an integrative hierarchical model with emotional schemas, mindfulness, and self-compassion was found with significant predictive value of psychological needs, without unconditional selfacceptance (non-confirmation of hypothesis 6). Self-compassion was the best predictor of the regulation of psychological needs. One likely explanation may be that being compassionate towards oneself may be one important mechanism that soften the self-criticism and punitive side, which may help individuals to pay more attention to their needs (Gilbert, 2010; Greenberg, 2015; Neff, 2003; Vasco et al., 2018).

Different mediation models were found between emotional schemas and symptomatology. In isolation, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion mediated the relationship between emotional schemas and symptomatology. However, in the composite model only self-compassion showed to be a significant mediator (partial confirmation of hypothesis 7). One possible explanation for these results may be that individuals who are driven by negative expectations and interpretations may have different degrees of mindfulness skills, unconditional self-acceptance and self-compassion which may result in different levels of symptomatology. Thus, non-acceptance/understanding and invalidation of the emotional experience, may reinforce negative beliefs towards emotional experience, not allowing an assignment of adaptive meanings to the experience, which may promote symptomatology (Greenberg 2015; Vasco, 2013). Another explanation regarding the composite mediation model may be related with the shared variance or the similarities between mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion (Neff, 2003; Thim, 2017). However, more research is required to address this issue. Nevertheless, these variables in addition may have a protective effect on reducing symptomatology by the previous referred soothing mechanisms.

Furthermore, in isolation, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion mediated the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs. In the composite model, only mindfulness and self-compassion were significant mediators of the relationship between emotional schemas and psychological needs (partial confirmation of hypothesis 8). This could be related to our previous explanation about how self-compassion may function as an adaptive self-stance that moderates the self-critical and punitive side, being this essential to soften symptoms of emotional pain and psychological distress. (Gilbert, 2010; Greenberg, 2015; Neff, 2003). These results support our previous arguments that emotional schemas may impair the regulation of psychological needs because they impair the emotional system which is responsible for signaling the degree of the underegulation or overregulation. Thus, emotional schemas are the dysfunctional beliefs and coping strategies that individuals use to deal with emotional experiences which in turn may promote symptomatology. However, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance, and self-compassion may mediate the relationship between emotional schemas and the regulation of psychological needs through mechanisms, such as, openness to internal experience/emotional awareness, self-acceptance of internal flaws and by reducing self-criticism and punishment. This is a new evidence because it is the first time that these variables are studied in combination, which means that more research is required to explore and to deepen the relationships between mindfulness, self-acceptance, self-compassion, emotional schemas and psychological needs.

Implications for Psychotherapy

These results may have some implications for psychotherapy, and they call for moment-to-moment and temporal sequence of phase-to-phase responsiveness (Vasco et al., 2018). First, the regulation of psychological needs may be viewed as the core factor to reduce symptomatology, psychological distress and to improve mental health. To work on the regulation of psychological needs, maybe a transtheoretical and integrative view of case conceptualization and clinical decision making may be needed due to the diversity associated constructs. Second, if the emotional system is the one who signals the degree of the regulation of psychological needs and emotional schemas tend to impair this system, then emotional schemas may be addressed through emotion focused tasks, such as focusing, imagery, chair work and behavioral rehearsal to skill development and schema restructuring. Third, mindfulness, unconditional self-acceptance and self-compassion may be viewed as adaptive states of mind or personality traits which function as an adaptive self-domain that may soothe emotional suffering and discomfort. Forth, these self-domains may function as an “antidote” for several problems, namely, mindfulness to counter experiential avoidance, self-acceptance to counter self-rejection, natural human flaws and devaluation and self-compassion to counter self-criticism, and pessimism. Five, in this sense these self-domains may be targets for case conceptualization to be improved through the psychotherapeutic process, due to its protective effect on symptomatology. Finally, these variables may be attached to sequence phase-to-phase interventions based on strategic therapeutic objectives in the psychotherapeutic process. However, more research is needed to explore how to promote mindfulness, self-acceptance, and self-compassion in temporal sequence according to patients’ timings, styles of communication and needs.

Limitations and Future Issues

Some limitations should be considered. First this research was based on a cross-sectional design which limits causality extrapolations. Second, our sample was based mainly on female university students which may led to some statistical tests being biased by a gender effect. Third, our sample is a non-clinical sample which may also limit the extrapolation to clinical samples. Fourth, this study used self-reported measures which are dependent of the individual’s self-awareness. In this sense, more research is required to replicate these findings in other nonclinical and clinical samples. Thus, these results need further validation through replication and consistency in fundamental research, case reports and outcome studies.

In the future, it is expected to compare a non-clinical sample with a clinical samples and to study the transdiagnostic potential of the variables. The aim is to investigate the relationships between emotional schemas, psychological needs, mentalization and states of mind in a complementary and integrative perspective. It would also be interesting to deepen the level of explanation of the relationships between early maladaptive schemas, emotional schemas, and interpersonal schemas. Due to the quantity and complexity of the variables under study, it was not possible to investigate the core relationships among these constructs (e.g., correlations between emotional schemas domains and specific needs, correlations between mindfulness traits, self-compassion domains and dimensions of symptomatology). However, in the future, we intend to address this issue.

Conclusions

Emotional schemas, mindfulness, self-compassion, unconditional self-acceptance and psychological needs may be viewed as transtheoretical variables related to each other and associated with symptomatology. This work highlights the ongoing need to study and develop a complementary view towards psychotherapy integration based on a transtheoretical perspective and empirical findings. Furthermore, we are focused on the identification of patient's core clinical variables associated with the regulation of psychological needs.

Funding Statement

Funding: this work was supported by a PhD grant, provided by the University of Lisbon, Portugal.

References

- Bardeen J. R., Fergus T. A. (2016). The interactive effect of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance on anxiety, depression, stress and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(1), 1-6. doi:10.1016/ j.jcbs.2016.02.002 [Google Scholar]

- Barreira J. (2016). [Relações entre dificuldades de processamento emocional, regulação emocional, necessidades psicológicas, sintomatologia e bem-estar/distress.) [Relationship between emotional processing difficulties, emotional regulation, psychological needs, symptomatology, and well-being/distress.) Master thesis in Faculty of Psychology of University of Lisbon. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/27559 [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Rush A. J., Shaw B., Emery G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Canavarro M. C. (1999). [Inventário de sintomas psicopatológicos –BSI.] Simões M. R., Gonçalves M., Almeida L. S. (Eds.), Testes e Provas Psicológicas em Portugal (Vol. II, pp.95-109). Braga: APPORT/SHO. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Castilho P., Pinto-Gouveia J., Duarte J. (2015). Evaluating the Multifactor Structure of the Long and Short Versions of the Self-Compassion Scale in a Clinical Sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(9), 856-870. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelo-Branco M. (2016). [Relações entre regulação emocional, regulação da satisfação das necessidades psicológicas, bemestar/ distress psicológicos e sintomatologia.] Master thesis in the Faculty of Psychology of University of Lisbon. (Relationships between emotional regulation, regulation of the satisfaction of psychological needs, psychological well-being/ distress and symptomatology). Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/25628 [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A., Serretti A. (2009) Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Stress Management in Healthy People: A Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15, 593-600. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde E. (2012). [Dialéctica de polaridades de regulação da satisfação de necessidades psicológicas: Relações com o bem-estar e distress psicológicos]. (Dialectic of polarities of regulation of psychological needs satisfaction: Relationships with psychological well-being and distress). Master’s thesis, Faculty of Psychology of University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8177 [Article in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição N., Vasco A. B. (2005). [Olhar para as necessidades como boi para um palácio: Perplexidades e fascínio.] Psychologica, 40, 55-73. [Article in Portuguese] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J., Pinto-Gouveia J. (2011). Acceptance of pain. Selfcompassion and psychopathology: Using the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire to identify patients’ subgroups. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 292–302. doi:10.1002/cpp.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E. R., Micek A., Monttarella K., Wupperman . P. (2016). Emotion Ideology Mediates the Effects of Risk Factors on Alexithymia Development. Journal of Rational- Emotional Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 35:254–277. doi 10.1007/s10942-016-0254-y [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E., Wupperman . P. (2018). Research on emotional schemas: A review of findings and challenges, Clinical Psychologist, 23(1), 3-14. doi:10.1111/cp.12171 [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R., Watson J. C., Goldman R. N., Greenberg L. S. (2004). Learning Emotion-Focused Therapy: The Process- Experiential Approach to Change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. (1994). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy: Revised and updated. New York: Carol Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Faustino B. (2020). Transdiagnostic Perspective on Psychological Inflexibility and Emotional Dysregulation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 1-14. doi:10.1017/S1352465820000600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino B., Fonseca I., Antonio A. B., Baião M., Lopes P., Oliveira (2019). [Esquemas Precoces Mal-adaptativos e Dificuldades Emocionais na Regulação das Necessidades Psicológicas: Um estudo com indicadores comportamentais.] (Early Maladaptive Schemas and Emotional Difficulties on Regulation of Psychological Needs: A study with behavioral indicators). Revista de Psicossomática ISSN – 2183-9344, 4. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Faustino B., Vasco A. B. (2020a). Schematic functioning, interpersonal dysfunctional cycles and cognitive fusion in the complementary paradigmatic perspective: Analysis of a clinical sample. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50, 47–55. doi:10.1007/s10879-019-09422-x [Google Scholar]

- Faustino B., Vasco A. B. (2020b). Early maladaptive schemas and cognitive fusion on the regulation of psychological needs. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50, 105–112. doi: 10.1007/s10879-019-09446-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino B., Vasco A. B. (2020c). Relationships between emotional processing difficulties and early maladaptive schemas on the regulation of psychological needs. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, doi: 10.1002/cpp.2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca J. M. (2012). [Relação entre a regulação da satisfação das necessidades psicológicas, funcionamento esquemático e alexithymia. Lisbon: Faculdade de Psicologia.] (Relationship between the regulation of satisfaction of psychological needs, schematic functioning and alexithymia]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8194 [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. (Ed.). (2005). Compassion: Conceptualizations, research and use in psychotherapy. New York, NY, US: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: distinctive features. The CBT distinctive features series. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415448079. OCLC 463971957. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P., McEwan K., Matos M., Rivis A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 84(3), 239-255. doi:10.1348/147608310X526511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L. S. (2015). Emotion-Focused Therapy: Coaching Clients to Work Through Their Feelings. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39, 281-291. doi:10.1017/S0048577201393198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F.(2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York:Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C., Strosahl K. D., Wilson K. G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S. G., Sawyer A. T., Witt A. A., Oh D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169-183. doi:10.1037/a0018555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (1982). An Outpatient Program in Behavioral Medicine for Chronic Pain Patients Based on the Practice of Mindfulness Meditation: Theoretical Considerations and Preliminary Results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4, 33-47. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion Leahy, R. L. (2015). Emotional schema therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. NewYork, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacBeth A., Gumley A. (2012). Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical psychology review, 32(6), 545–552. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins R. (2016). [Relações entre esquemas interpessoais, mecanismos de defesa, necessidades psicológicas, sintomatologia, bem-estar e distress psicológico. Lisbon: Faculdade de Psicologia da Universidade de Lisboa.] (Relations between interpersonal schemes, mechanisms of defense, psychological needs, symptomatology, Well-being and psychological distress). Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/28179 [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–102 [Google Scholar]

- Neff K. D., Hseih Y., Dejitthirat K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity, 4, 263–287 [Google Scholar]

- Palmeira L., Pinto-Gouveia P., Dinis A., Lourenço S. (2011). [O papel dos Emotional Schemas na transgeracionalidade do processo de socialização das emoções negativas.] Avaliação Psicológica em Contexto Clínico, 54, 439-646. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A., Greenberg L. S. (2007). Emotional processing in experiential therapy: Why “the only way out is through.” Journal of Consulting and ClinicalPsychology, 75(6), 875-887. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov S. (2019). When is Unconditional Self-Acceptance a Better Predictor of Mental Health than Self-Esteem? Journal of Rational-Emotive Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 37, 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10942-018-0310-x [Google Scholar]

- Popov S., Biro M., Radanović J. (2016). Unconditional selfacceptance and mental health in ego-provoking experimental context. Suvremena psihologija, 19(1), 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raes F. (2011). The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness, 2, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Raque-Bogdan T. L., Ericson S. K., Jackson J., Martin H. M., Bryan N. A. (2011). Attachment and mental and physical health: Self compassion and mattering as mediators. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 58, 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein L. R., Tirch D., Leahy R. L., McGinn L. (2012). Mindfulness, psychological flexibility, and emotional schemas. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4), 406-419. doi:10.1521/ijct.2012.5.4.406 [Google Scholar]

- da Silva A.N., Matos M., Faustino B, Dias Neto D. (2019). Portuguese Version of the Leahy Emotional Schema Scale (LESS). Poster presented in World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies at the CityCube, Berlin. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.21835.41769. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344283057_Portuguese_version_of_the_Leahy_Emotional_Schema_Scale_LESS?channel=doi&linkId=5f63244d92851c14bc818b1c&showFulltext=true [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z. V., Williams J. M. G., Teasdale J. D. (2013). Mindfulness- based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss C., Cavanagh K., Oliver A., Pettman D. (2014). Mindfulness-Based Interventions for People Diagnosed with a Current Episode of an Anxiety or Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 9(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirch D. D., Leahy R. L., Silberstein L. R., Melwani P. S. (2012). Emotional schemas, psychological flexibility, and anxiety: the role of flexible response patterns to anxious arousal. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4):380-91. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco A. B. (2001). Fundamentos para um modelo integrativo de “complementaridade paradigmática.” (Fundamentals for an integrative model of “paradigmatic complementarity”). Psicologia, 15(2), 219–226. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco A. B. (2005). [A conceptualização de caso no modelo de complementaridade paradigmática: variedade e integração.] Psychologica, 40, 11-36. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco A. B. (2013). [Sinto e Penso, logo Existo! Abordagem Integrativa das Emoções.] Revista Serviço de Psiquiatria do Hospital Prof Doutor Fernando Fonseca, EPE. 11. 1. Lisboa: Psilogos [Integrative Approach to Emotions]. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Vasco A. B., Conceição N., Silva A. N., Ferreira J. F., Vaz- Velho C. (2018). [O (meta) modelo de complementaridade paradigmática (MCP).] Leal I. (Ed.), Psicoterapias. Lisbon: Pactor. [Paradigmatic Complementarity Metamodel]. [Article in Portuguese]. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M., Leahy R. L., Pala A. N., Wupperman P. (2016). Self-compassion and emotional invalidation mediate the effects of parental indifference on psychopathology. Psychiatry Research, 242, 186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. E., Klosko J. S., Weishaar M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]