Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To explore the perspective of urological patients on the possibility to defer elective surgery due to the fear of contracting COVID-19.

METHODS

All patients scheduled for elective urological procedures for malignant or benign diseases at 2 high-volume centers were administered a questionnaire, through structured telephone interviews, between April 24 and 27, 2020. The questionnaire included 3 questions: (1) In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, would you defer the planned surgical intervention? (2) If yes, when would you be willing to undergo surgery? (3) What do you consider potentially more harmful for your health: the risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization or the potential consequences of delaying surgical treatment?

RESULTS

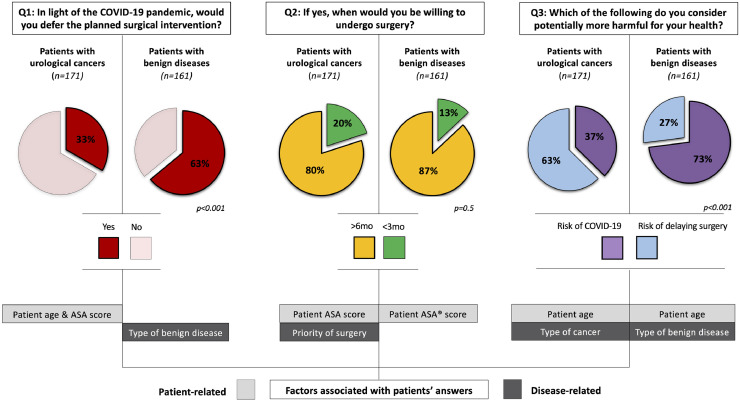

Overall, 332 patients were included (51.5% and 48.5% in the oncology and benign groups, respectively). Of these, 47.9% patients would have deferred the planned intervention (33.3% vs 63.4%; P < .001), while the proportion of patients who would have preferred to delay surgery for more than 6 months was comparable between the groups (87% vs 80%). These answers were influenced by patient age and American Society of Anesthesiologists score (in the Oncology group) and by the underlying urological condition (in the benign group). Finally, 182 (54.8%) patients considered the risk of COVID-19 potentially more harmful than the risk of delaying surgery (37% vs 73%; P < .001). This answer was driven by patient age and the underlying disease in both groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings reinforce the importance of shared decision-making before urological surgery, leveraging patients’ values and expectations to refine the paradigm of evidence-based medicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a global emergency with a major impact on healthcare systems worldwide. In this context, Urology has been significantly involved,1 with a dramatic reorganization of elective surgical activity1, 2, 3, 4 and a slowdown of Urology residents’ learning curve.5, 6, 7, 8 Several cross-sectional surveys, investigating the impact of COVID-19 on urological services worldwide, confirmed that the pandemic has imposed great challenges to urology healthcare providers. In fact, a significant cut-down in urology clinics, outpatient procedures, major surgeries, and urgent/emergent urological care has been reported.2 , 9

Soon after the spread of the pandemic, several National and International Urological Associations have provided timely recommendations to guide the prioritization of clinical and surgical activities during such a challenging context.10, 11, 12, 13 Although it may lead to potential clinical and medicolegal implications,14 , 15 the possibility that patients may want their elective surgery to be postponed, due to the fear of contracting COVID-19 during the hospitalization, was not formally taken into account.10, 11, 12, 13 Thus, the transferability of such recommendations to real-life clinical scenarios still needs to be investigated.

From the patient's standpoint, the choice to undergo surgery during such a complex period may be particularly challenging, considering the competing risks of delaying the intervention (with possible consequences on oncologic/functional outcomes) and contracting a potentially life-threatening disease.

Aiming to optimize the decision-making during emergency scenarios such as the COVID-19 pandemic, in this study we explored the patients’ perspective on the possibility to delay elective surgery and its drivers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

A specific questionnaire was developed to investigate whether patients, scheduled for elective urological procedures (for malignant or benign diseases) at 2 Italian high-volume referral centers, would have been willing to defer the planned intervention due to the fear of contracting COVID-19.

Four urology residents administered the questionnaire to all patients through structured telephone interviews between April 24 and 27, 2020.

To be included in the study, patients had to be considered eligible for surgery after a thorough anesthesiologic work-up.

The priority of uro-oncological procedures (low vs high) was classified according to previously published criteria.11 In detail, radical cystectomy, radical nephroureterectomy, transurethral resection of bladder tumor, endoscopic management of upper urinary tract urothelial cancer, radical prostatectomy for high-risk patients if not eligible for radiation, orchifuniculectomy for testicular cancer and any treatment for penile cancer were considered as high-priority uro-oncological procedures. On the other hand, all treatments for oncologic diseases not fulfilling these criteria were included in low-priority surgeries.

Regarding benign conditions, upper tract functional diseases included ureteropelvic junction obstruction, large renal cysts compressing the pelvicalyceal system, ureteral stenosis requiring ureteral stent placement, while female functional diseases included urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Finally, andrological diseases included hydrocele, varicocele, and erectile dysfunction.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as histopathological data, were obtained from our prospectively collected Institutional databases.

Study Questionnaire

The study questionnaire included the following questions (Q):

Q1: In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, would you defer the planned surgical intervention?;

Q2: If yes, when would you be willing to undergo surgery? (not beyond 3 months versus 6 months or more);

Q3: What do you consider potentially more harmful for your health: the risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization or the potential consequences of delaying surgical treatment?`

Patients’ answers were recorded in a priori developed database.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of the study was the proportion of patients willing to defer their planned surgical intervention if scheduled during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An exploratory analysis was performed to evaluate the potential influence of patient- and/or disease-specific characteristics on such perspective.

Descriptive statistics were reported as the median and interquartile range for continuous variables, and the frequency and proportion for categorical variables, as appropriate.

The potential influence of baseline characteristics on patients’ answers was evaluated by the Pearson Chi-square or Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 24 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, Armonk, NY, IBM Corp). All tests were two-sided with a significance set at P < .05.

Results

Overall, 358 patients met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 332 (93%) were included in the analytic cohort. Reasons for exclusion were (1) patient death while on the waiting list (n = 4); (2) impossibility to reach the patient via telephone (or email) (n = 21); (3) cancellation of the planned intervention (n = 1).

Of the included patients, 171 of 332 (51.5%) were scheduled for oncologic surgery, of which 19.5% classified as high-priority (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Included in the Study and Main Study Outcomes

| Patient Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Center (n,%) | Florence | 224 (67.5) |

| Turin | 108 (32.5) | |

| Age (years) (n,%) | ≤60 | 82 (24.7) |

| 61-80 | 209 (63.0) | |

| >80 | 41 (12.3) | |

| Level of education (n,%) | Primary/secondary school | 143 (43.1) |

| High school/University | 189 (56.9) | |

| ASA score (n,%) | 1-2 | 256 (77.1) |

| 3-4 | 76 (22.9) | |

| Disease characteristics | ||

| Nature of the disease (n,%) | Benign | 171 (51.5) |

| Malignant | 161 (48.5) | |

| Type of benign disease (n,%) | Stone / Upper tract functional disease | 43 (26.7) |

| Andrological disease | 25 (15.5) | |

| BPH / female functional disease | 93 (57.8) | |

| Type of cancer (n,%) | Prostate Cancer | 67 (38.7) |

| Urothelial Cancer | 77(44.5) | |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 29 (16.8) | |

| Priority of uro-oncologic surgery (according to Stensland et al2) |

High Priority | 51 (19.5) |

| Low Priority | 210 (80.5) | |

| Main outcomes | ||

| Q1: In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, would you defer your planned surgical intervention? (n,%) | Yes | 159 (47.9) |

| No | 173 (52.1) | |

| Q2: If yes, when would you be willing to undergo surgery? (n,%) (n = 159) | <3 months | 24 (15.1) |

| >6 months | 135 (84.9) | |

| Q3:Which of the following do you consider potentially more harmful for your health? (n,%) | Risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization | 182 (54.8) |

| Risk of delaying surgical treatment | 150 (45.2) | |

BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia.

The main study results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2 .

Figure 1.

Patients’ perspectives on refusal of elective urological surgery and their drivers, stratified by the nature of underlying urological condition (malignant disease [group A] vs benign disease [group B]). The factors influencing the answers to questions Q1-Q3 are shown in the lower portion of the figure and are highlighted in light grey (for patient-related variables) and dark grey (for disease-related variables). ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists. (Color version available online.)

Table 2.

Influence of Patient- and Disease-related Characteristics on Patients’ Perspective Regarding the Refusal of Elective Surgery in Our Study Population

| Patients With Urological Cancers (n = 171) | Age (Y) |

p | Education |

p | ASA Score |

p | Type of Cancer |

P | Priority of Uro-oncological Surgery |

p | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 | 61-80 | > 80 | Primary / Secondary School | High-School / University | ASA 1-2 | ASA 3-4 | Prostate | Urothelial | Renal | Low | High | |||||||

| Q1: In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, would you defer the planned surgical intervention? | 7 (21.2) | 34 (31.2) | 16 (55.2) | 0.01 | 30 (37.5) | 27 (29.7) | 0.3 | 36 (29.0) | 21 (44.7) | 0.03 | 21 (31.8) | 30 (39.5) | 6 (20.7) | 0.2 | 42 (34.4) | 15 (30.6) | 0.6 | |

| Q2: If yes, when would you be willing to undergo surgery? (n=57) | <3 months | 1 (14.3) | 8 (23.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0.3 | 6 (20.0) | 4 (14.8) | 0.6 | 3 (8.3) |

7 (33.3) | 0.01 | 3 (14.3) | 7 (23.3) | 0 (0) | 0.4 | 5 (11.9) | 5 (33.3) | 0.045 |

| >6 months | 6 (85.7) | 26 (76.5) | 15 (93.8) | 24 (80.0) | 23 (85.2) | 33 (91.7) | 14 (66.7) | 18 (85.7) | 23 (76.7) | 6 (100) | 37 (88.1) | 10 (66.7) | ||||||

| Q3: Which of the following do you consider potentially more harmful for your health: | Risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization | 9 (27.3) | 35 (32.1) | 20 (69.0) | 0.01 | 36 (45.0) | 28 (30.8) | 0.041 | 42 (33.9) | 22 (46.8) | 0.1 | 19 (28.8) | 38 (50.0) | 7 (24.1) | 0.009 | 48 (39.3) | 16 (32.7) | 0.4 |

| Risk of delaying surgery | 24 (72.7) | 74 (67.9) | 9 (31.0) | 44 (55.0) | 63 (69.2) | 82 (66.1) | 25 (53.2) | 47 (71.2) | 38 (50.0) | 22 (75.9) | 74 (60.7) | 33 (67.3) | ||||||

| Patients With Benign Diseases (n = 161) | Age (Y) |

p | Education |

p | ASA Score |

p | Type of Benign Condition |

p | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 | 61-80 | > 80 | Primary / Secondary School | High-School / University | ASA 1-2 | ASA 3-4 | Stone / Upper Tract Functional | Andrology | BPH / Female Functional | |||||||||

| Q1: In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, would you defer the planned surgical intervention? | 25 (51.0) | 69 (69.0) | 8 (66.7) | 0.1 | 41 (65.1) | 61 (62.2) | 0.7 | 83 (62.9) | 19 (65.5) | 0.8 | 21 (48.8) | 15 (60.0) | 66 (71.0) | 0.004 | ||||

| Q2: If yes, when would you be willing to undergo surgery? (n=102) | <3 months | 3 (12.0) | 11 (15.9) | 0 (0) | 0.4 | 9 (22.0) | 5 (8.2) | 0.04 |

6 (7.2) |

8 (42.1) | 0.001 | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 10 (15.2) | 0.2 | |||

| >6 months | 22 (88.0) | 58 (84.1) | 8 (100) | 32 (78.0) | 56 (91.8) | 77 (92.8) | 11 (57.9) | 17 (81.0) | 15 (100) | 56 (84.8) | ||||||||

| Q3: Which of the following do you consider potentially more harmful for your health: | Risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization | 29 (59.2) | 80 (80.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.02 | 46 (73.0) | 72 (73.5) | 0.9 | 96 (72.7) | 22 (75.9) | 0.7 | 26 (60.5) | 18 (72.0) | 74 (79.6) | 0.039 | |||

| Risk of delaying surgery | 20 (40.8) | 20 (20.0) | 3 (25.0) | 17 (27.0) | 26 (26.5) | 36 (27.3) | 7 (24.1) | 17 (39.5) | 7 (28.0) | 19 (20.4) | ||||||||

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Data are presented separately for the cohort of patients scheduled for uro-oncological surgery and for those scheduled for surgery for benign urological conditions.

Bold values are those that are “statistically significant” (p<0.05).

Overall, 159 (47.9%) patients would have deferred the planned surgical intervention in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, with nearly 85% of them willing to postpone it for at least 6 months.

The proportion of patients refusing surgery was significantly higher among those with benign conditions as compared to those with cancer (63.4% vs 33.3%; P < .001) (Fig. 1 -Q1).

In the oncologic disease group, the will to postpone surgery was more pronounced among older (21.2% vs 31.2% vs 55.2% for patients aged <60 years, 61-80 years and >80 years, respectively, P = .01) and frailer (44.7% vs 29.0% for American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score ≥3 vs ASA score <3, P = 0.03) patients. On the contrary, the priority of surgery did not influence this answer (30.6% vs 34.4% for high- vs low-priority, respectively, P = .6).

Conversely, in the benign disease group, the underlying urological condition was the only factor impacting on the attitude to defer the procedure. Namely, interventions for benign prostatic hyperplasia/female functional diseases and andrological diseases were more frequently asked to be deferred as compared to those for urolithiasis/related conditions (71.0% vs 68.8% vs 48.8%, respectively, P = .004).

The proportion of patients wishing to delay surgery for more than six months was not significantly different among the two groups (87% vs 80% in the benign and oncology groups, respectively, P = .5) (Fig. 1 -Q2).

Frailer patients (ASA ≥3) were less likely to postpone surgery for at least 6 months in both cohorts (57.9% vs 92.8%, P = .001 and 66.7% vs 91.7%, P = .01 in the benign and oncology groups, respectively). Moreover, among patients with oncologic diseases, this answer was also influenced by the priority of surgery (88.1% vs 66.7% for low- vs high-priority, respectively, P = .048).

Overall, 182 (54.8%) patients considered the risk of contracting COVID-19 during hospitalization potentially more harmful than the risk of delaying surgery. This proportion was significantly higher among patients with benign conditions (73% vs 37%, P < .001) (Fig. 1 -Q3). In both groups, the underlying urological condition and patient age significantly influenced this perspective (Table 2). Older patients were indeed more worried about the risk of COVID-19 (oncology group: 27.3% vs 32.1% vs 69.0%, P = .01; benign group: 59.2% vs 80.0% vs 75.0%, P = .02, for patients aged <60 years, 61-80 years and >80 years, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Shared decision-making is a key component of patient-centered health care. It is defined as an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions, aiming to achieve informed preferences.16 In this view, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study exploring how patients scheduled for elective urological procedures perceive their disease and the risk-benefit ratio of undergoing surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our findings provide insights to contextualize and reinforce the value of shared decision-making in such an unprecedented period, providing an opportunity to refine both the available schemes for triage of urological procedures12 and waiting lists, taking into account patients’ wishes and fears.

The compelling need to value the patients’ perspective (beyond disease-specific features) during preoperative counseling is real both for oncologic and nononcologic settings.17 In fact, in light of the recommendations provided by most Urological Associations worldwide, the procedures that are most likely to impact on the burden of urologists’ workload in the future are represented by elective surgeries for lower risk cancers and selected benign conditions such as nonobstructing stone disease and Benign prostatic hyperplasia.10

A first key finding of our study is that around 1 out of 3 patients with urological cancers would have deferred surgery, even if classified as high-priority. As such, these patients will likely represent a challenge for rescheduling waiting lists in the near future, being approximately one-third of elective cancer surgeries at referral centers.18 Moreover, the finding that elderly and frailer patients were more prone to postpone surgery, in light of a higher fear of contracting COVID-19, further highlights the need for careful selection of surgical candidates in this patient population.10 It is important to note that, while the proportion of cancer patients declining intervention during the “acute” phase of the outbreak ranged between 5% and 20% at our Centres,16 the patients included in the current study were interviewed in a later phase of the pandemic, when both the Government and the mass media were discussing the concrete possibility to reduce the lockdown. This underlines the importance of shared decision-making, as well as of structured care pathways, in patients scheduled for uro-oncological surgery during emergency periods.18, 19, 20, 21. In this light, emerging proposals assessing the benefits of counseling and visits through telemedicine tools have shown encouraging insights.22

Notably, in the nononcologic setting, around one-third of patients with benign diseases were less likely to refuse surgery, being more concerned about the potential consequences of delaying intervention (Table 1). These patients might be those with a higher burden of symptoms and worse quality of life, reinforcing the need for careful patient counseling.

Despite its novelty, our study is not devoid of limitations. First, it was conducted at the end of the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, our findings might not reflect patients’ perspectives during the peak of the emergency.

Second, the questionnaire was administered to patients scheduled for elective surgery at 2 high-volume referral centers, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results to other health care scenarios. Third, we could not assess whether the presence of symptoms might have influenced patients’ answers.

Acknowledging these limitations, our study reinforces the importance of shared decision-making during emergency periods such as the COVID-19 pandemic, providing an opportunity to reinterpret the available schemes for triage of urologic procedures in light of patients’ values and expectations.10 , 22

CONCLUSION

In this study, we explored the patients’ perspective on the possibility to delay elective urologic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic, offering insights to contextualize and reinforce the value of shared decision-making also beyond such an unprecedented scenario.

In light of our findings, the paradigm of evidence-based medicine in the COVID-19 era and in the near future will require not only integration of clinical expertise with the best available evidence, but also a careful consideration of individual patients’ values and expectations.

Future research efforts should aim at integrating such patients’ views into effective strategies to reorganize Urology practice in the upcoming phases of the pandemic.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:None to report.

Financial Disclosure:The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Ficarra V, Novara G, Abrate A. Urology practice during COVID-19 pandemic. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2020 doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03846-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teoh JYC, Lay Keat Ong W, Gonzalez-Padilla D. A Global survey on the impact of COVID-19 on urological services. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.05.025. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luciani LG, Mattevi D, Giusti G. Guess who's coming to dinner: COVID-19 in a COVID-free unit. Urology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.011. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puliatti S, Eissa A, Eissa R. COVID-19 and urology: a comprehensive review of the literature. BJU Int. 2020;125:E7–E14. doi: 10.1111/bju.15071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amparore D, Claps F, Cacciamani GE. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urology residency training in Italy. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2020;10:23736. doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03868-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porpiglia F, Checcucci E, Amparore D. Slowdown of urology residents' learning curve during the COVID-19 emergency. BJU Int. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bju.15076. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargo E, Ali M, Henry F. Cleveland Clinic Akron General Urology Residency Program's COVID-19 Experience [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 2] Urology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon YS, Tabakin AL, Patel HV. Adapting urology residency training in the COVID-19 era. Urology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.065. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porreca A, Colicchia M, D'Agostino D. Urology in the time of coronavirus: reduced access to urgent and emergent urological care during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Italy. Urol Int. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000508512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amparore D, Campi R, Checcucci E. Forecasting the future of Urology practice: a comprehensive review of the recommendations by International and European Associations on priority procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol Focus. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2020.05.007. S2405-4569(20)30142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stensland KD, Morgan TM, Moinzadeh A. Considerations in the triage of urologic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.027. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribal MJ, Cornford P, Briganti A. EAU Guidelines Office Rapid Reaction Group: an organisation-wide collaborative effort to adapt the EAU guidelines recommendations to the COVID-19 era. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.056. https://www.europeanurology.com/covid-19-resourceEAU In Press. Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman HB, Haber GP. Recommendations for tiered stratification of urologic surgery urgency in the COVID-19 era. J Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001067. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ficarra V, Mucciardi G, Giannarini G. Re: Riccardo Campi, Daniele Amparore, Umberto Capitanio, et al. Assessing the burden of urgent major uro-oncologic surgery to guide prioritisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from three Italian high-volume referral centres. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.054. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryan AF, Milner R, Roggin KK. Unknown unknowns: surgical consent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surgery. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003995. https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Documents/Unknown%20unknowns%20.pdf In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morlacco A, Motterle G, Zattoni F. The multifaceted long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on urology. Nat Rev Urol. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campi R, Amparore D, Capitanio U. Assessing the burden of nondeferrable major uro-oncologic surgery to guide prioritisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from three Italian high-volume referral centres. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.054. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campi R, Amparore D, Capitanio U. Reply to Vincenzo Ficarra, Giuseppe Mucciardi, and Gianluca Giannarini's Letter to the Editor re: Riccardo Campi, Daniele Amparore, Umberto Capitanio, et al. Assessing the burden of nondeferrable major uro-oncologic surgery to guide prioritisation strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from three Italian high-volume referral centres. Eur Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.054. https://www.europeanurology.com/covid-19-resourceEAU [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borchert A, Baumgarten L, Dalela D. Managing urology consultations during COVID-19 pandemic: application of a structured care pathway. Urology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.059. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 21] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan YQ, Wang Z, Tiong HY. The START (Surgical Triage And Resource Allocation Tool) of surgical prioritisation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.021. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amparore D, Campi R, Checcucci E. Patients’ perspective on the use of telemedicine for outpatient urological visits: learning from the COVID-19 outbreak. Actas Urol Esp. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.06.008. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]