Abstract

Purpose

There is widespread accord among economists that the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will have a severe negative effect on the global economy. Establishing new radiation therapy (RT) infrastructure may be significantly compromised in the post–COVID-19 era. Alternative strategies are needed to improve the existing RT accessibility without significant cost escalation. The outcomes of these approaches on RT availability have been examined for Asia.

Methods and Materials

The details of RT infrastructures in 2020 for 51 countries in Asia were obtained from the Directory of Radiotherapy Centers of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Using the International Atomic Energy Agency guidelines, the percent of RT accessibility and the additional requirements of teletherapy (TRT) units were computed for these countries. To maximize the utilization of the existing RT facilities, 5 options were evaluated, namely, hypofractionation RT (HFRT) alone, with/without 25% or 50% additional working hours. The effect of these strategies on the percent of RT access and additional TRT unit requirements to achieve 100% RT access were estimated.

Results

In 46 countries, 4617 TRT units are available. The mean percent of RT accessibility is 62.4% in 43 countries (TRT units = 4491) where the information on cancer incidence was also available, and these would need an additional 6474 TRT units for achieving 100% RT accessibility. By adopting HFRT alone, increasing the working hours by 25% alone, 25% with HFRT, 50% alone, and 50% with HFRT, the percent of RT access could improve to 74.9%, 78%, 90.5%, 93.7%, and 106.1%, respectively. Correspondingly, the need for additional TRT units would progressively decrease to 4646, 4284, 3073, 2820, and 1958 units.

Conclusions

The economic slowdown in the post–COVID-19 period could severely impend establishment of new RT facilities. Thus, maximal utilization of the available RT infrastructure with minimum additional costs could be possible by adopting HFRT with or without increased working hours to improve the RT coverage.

Introduction

The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is expected to result in severe contraction of the global economy.1,2 According to the World Bank, the pandemic is likely to plunge the economy of most countries into recession, with per capita income shrinking in the majority of countries to magnitudes not seen since 1870.3 In 2020 itself, the global economy is projected to contract by 4.93%.4 Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic would also have an adverse effect on the targets of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDG) proposed to be achieved by 2030.5,6 This would certainly have widespread ramifications in nearly all sectors including health care, in particular, for the diagnosis and treatment of noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, which require large investments. For cancer, expected to have a rising trend of incidence globally from 18.98 million in 2020 to 24.11 million in 2030, the allocation of funds toward cancer care in the near future could be severely curtailed.7

Radiation therapy (RT), one of the essential components of multimodality cancer management, is capital intensive.8, 9, 10 Even today, the available RT infrastructure and complementary human resources are insufficient to meet the growing RT demands, especially in the low- and middle-income economies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 The situation is likely to worsen, as most countries may find it difficult to designate adequate finances for establishing new RT infrastructure in the post–COVID-19 era.

As per the Global Cancer Observatory, in 2020, a cancer incidence of 9.22 million and mortality of 5.79 million in Asia would account for nearly 48.5% and 57.6% of the global cancer incidence and mortality, respectively.7 This is the highest among all 5 continents. It therefore becomes imperative to explore alternative strategies in the post–COVID-19 era to maximize the available RT resources with minimal cost escalation so as to improve RT accessibility even with the existing RT set-up. This needs a systematic assessment of the magnitude of the present crisis, the challenges it poses, and the opportunities that may evolve. The present study is therefore directed toward examining quantitatively the effect of various strategies to improve RT accessibility with existing RT infrastructure, taking Asia as an example.

Methods and Materials

Data sources

The UN Population Division includes 51 countries in the Asian continent.17 They have been classified into low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs) based on their gross national income (GNI) per capita.18 The cancer incidence for “all cancers excluding nonmelanoma cancer” for each country in 2020 was extracted from the Global Cancer Observatory.7 Details of the existing RT infrastructure were obtained from the DIrectory of Radiotherapy Centres (DIRAC) of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on May 17, 2020.19

Computation of the RT infrastructure

According to the IAEA recommendations, the demand for megavoltage units for each country was quantified assuming an optimum RT utilization rate of 55%. The reirradiation rate was assumed as 10%; thus 60.5% of all cancers would require RT.14 Further, a single teletherapy (TRT) unit would treat 500 new patients annually using routine techniques within the normal 8 hours of work time of a department.14,15 Using these benchmarks and the cancer incidences, the requirement for additional TRT units for 100% RT access in 2020 for each country was computed. The details of the available human resources regarding RT (radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and RT technologists) in these countries could not be assessed, as information on various personnel was not available in the present DIRAC database.19

Strategies for maximal utilization of RT infrastructure with minimal cost escalation

It is assumed that RT centers presently functioning have adequate RT personnel to run their existing facilities for 8 hours of normal working time of a department. Thus, the various approaches that were considered for increasing patient throughput from 500 patients/TRT unit/y with minimal cost escalation are

-

1.

Hypofractionated RT (HFRT) within 8 working hours of a department: It is assumed that in a routine department, patients undergoing radical, postoperative, or preoperative RT are usually treated with standard fractionation RT (SFRT) schedules of 70 Gy/35 fractions/7 wk, 60 Gy/30 fractions/6 wk, and 50 Gy/25 fractions/5 wk, and annually these constitute around 30%, 30%, and 20% of patients, respectively. The remaining 20% of the patients are treated with palliative RT to doses of 30 Gy/10 fractions/2 weeks (10%) and <20 Gy/5 fractions/1 week (10%) (Table E1). Most patients considered for palliative treatment with <20 Gy present with bone metastasis. They are likely to be treated by single fraction as this has been shown to be equally effective as multiple fraction RT.20 These assumptions are based on the first author's experience of working at several centers in an Asian country. However, individual centers in different countries could review their own patient data and distribution of patients subjected to different RT treatment fractionation plans based on the current practices prevalent in a particular center. Accordingly, they could alter these values to conform to their patient population and RT time-dose fractionation schedules.

A mild to moderate HFRT could be adopted whereby the treatment durations for radical, postoperative, preoperative, and the 2-week palliative RT schedule are reduced by 1 week, each keeping the respective total RT doses the same. Correspondingly, this would result in a dose/fraction of 2.33 Gy, 2.40 Gy, 2.5 Gy, and 3 Gy for these treatments. The biologically effective doses (BED) for early effects with time factor for both SFRT and HFRT schedules could be computed using the linear-quadratic model, assuming α/β = 10 Gy, α = 0.3 Gy-1, potential doubling time, Tpot = 5 days, and kick-off time = 21 days.21 The BED for late effects for all regimens was computed assuming α/β = 3 Gy.

As evident from Table E1, the additional number of patients who could be treated by changing from SFRT to HFRT would be >80 patients/TRT unit/y. Depending on the choice of single or multiple (1-5 fractions/1 wk) RT fractions for palliation, the number of additional patients treated with <20 Gy/1 week could even exceed by 0 to 200/y. This would depend on the proportion of patients treated with single or multiple palliative RT fractions at a center. For computational purposes, a conservative value of 100 additional patients/TRT unit/y has been assumed. Thus, at least 600 patients/TRT unit/y could be added with HFRT treatment within the usual 8 working hours of a department.

-

2.

Additional 25% working hours with SFRT: By increasing the working hours by 25% (2 additional hours for a typical 8-hour work day of a department), an additional 125 patients could be accommodated per year. As a result, the estimated number of patients who could be treated by each TRT unit/y could increase to 625.

-

3.

Additional 25% working hours with HFRT: Using a combination of the strategies (a) and (b), an additional 225 patients could be treated, thereby allowing 725 patients to be treated annually in a TRT unit.

-

4.

Additional 50% working hours with SFRT: A 50% increase of working hours by 4 additional hours with SFRT could increase the annual number of patients treated in a single TRT unit by 250, thus bringing the total number to 750 patients/TRT unit/y.

-

5.

Additional 50% working hours with HFRT: A 50% increase of working hours with HFRT could increase the annual number of patients treated in a single TRT unit by 250. Consequently, 850 patients could be treated per TRT unit annually.

Results

Data demography

The 51 countries in Asia presently have a population of 4.64 billion. This constitutes around 59.5% of the global population.17 The cancer incidence data in 2020 were available for 47 countries, whereas the RT infrastructure was listed in the DIARC database for 46 countries (Table E2).7,19 The GNI/capita could be assessed in 46 countries. Accordingly, 32 countries were classified as LMICs (GNI/capita less than United States [U.S.] $12,375), 14 as HICs (GNI/capita ≥U.S. $12,376), and 5 countries remained unclassified as their GNI/capita was not available.22 The percent of RT accessibility and the need for additional TRT units could only be evaluated if both the cancer incidence and the present RT infrastructure details were available. Thus, both these estimates and the effect of the various options to maximize the available RT infrastructure resource utilization were available for 43 of the 51 countries (hereinafter called the “43 target countries”).

Magnitude of the existing RT accessibility

The Global Cancer Observatory projects a cancer incidence of 9.08 million in 47 of the 51 countries in Asia (Table E2).7 Thus, around 5.49 million of these patients would be expected to need RT. Presently, in the 43 target countries, 2973 RT centers have 4491 megavoltage TRT units (range, 1-1644) and 817 brachytherapy (BRT) facilities (range, 0-314). In addition, 28 particle therapy units are available, of which 21 are in Japan.

The percent of RT access in 43 target countries is extremely heterogeneous. It ranges between 4.3% and 174.7% (mean ± standard deviation, 62.4% ± 45.0%; median, 32%; Tables 1 and E2). The mean percent of RT accessibility is 50.7%, 99.8%, and 29.6% in LMICs, HICs, and unclassified countries, respectively (Table E2). Presently, only 7 countries have adequate TRT units to provide 100% RT coverage. For 100% RT access in 2020 for these 43 countries, 6474 additional TRT units would be required (mean ± standard deviation, 150 ± 590.4; median, 8; range, -5-3818). The additional TRT units required for the LMICs, HICs, and unclassified countries were 5987, 360, and 127, respectively.

Table 1.

Changes in the percentage of RT access and additional teleradiotherapy unit requirements for all countries in Asia with various strategies to maximize utilization of RT infrastructure

| Countries | With SFRT and 8 working hours |

With HFRT and 8 working hours |

+25% working hours and SFRT |

+25% working hours and HFRT |

+50% working hours and SFRT |

+50% working hours and HFRT |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | Percent RT access | Additional TRT units | |

| Afghanistan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Armenia | 27.2 | 8 | 32.7 | 6 | 34.1 | 6 | 39.5 | 5 | 13.6 | 4 | 46.3 | 3 |

| Azerbaijan | 67.1 | 5 | 80.5 | 2 | 83.9 | 2 | 97.3 | 0 | 33.6 | 0 | 114.1 | –1 |

| Bahrain | 141.5 | –1 | 169.8 | –1 | 176.9 | –1 | 205.2 | –1 | 70.8 | –1 | 240.6 | –1 |

| Bangladesh | 18.0 | 159 | 21.6 | 127 | 22.5 | 120 | 26.1 | 99 | 9.0 | 94 | 30.7 | 79 |

| Bhutan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunei | 166.5 | –1 | 199.7 | –1 | 208.1 | –1 | 241.4 | –1 | 83.2 | –1 | 283.0 | –1 |

| Cambodia | 10.1 | 18 | 12.1 | 14 | 12.6 | 14 | 14.7 | 12 | 5.1 | 11 | 17.2 | 10 |

| China | 30.1 | 3818 | 36.1 | 2908 | 37.6 | 2726 | 43.6 | 2123 | 15.0 | 1998 | 51.2 | 1569 |

| Cyprus | 113.8 | –1 | 136.6 | –2 | 142.3 | –2 | 165.0 | –3 | 56.9 | –3 | 193.5 | –3 |

| Democratic People's Republic, Korea | 4.3 | 67 | 5.2 | 55 | 5.4 | 53 | 6.2 | 45 | 2.1 | 44 | 7.3 | 38 |

| Georgia | 139.9 | –5 | 167.9 | –6 | 174.9 | –7 | 202.9 | –8 | 70.0 | –8 | 237.9 | –9 |

| Hong Kong | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| India | 43.2 | 838 | 51.9 | 592 | 54.0 | 543 | 62.7 | 380 | 21.6 | 346 | 73.5 | 230 |

| Indonesia | 13.4 | 386 | 16.1 | 312 | 16.8 | 297 | 19.5 | 248 | 6.7 | 237 | 22.9 | 202 |

| Iran, Islamic Republic of | 85.0 | 21 | 102.0 | –2 | 106.2 | –7 | 123.2 | –23 | 42.5 | –26 | 144.5 | –37 |

| Iraq | 57.8 | 14 | 69.3 | 8 | 72.2 | 7 | 83.8 | 4 | 28.9 | 3 | 98.2 | 0 |

| Israel | 100.1 | 0 | 120.1 | –6 | 125.1 | –7 | 145.1 | –11 | 50.0 | –11 | 170.1 | –14 |

| Japan | 86.0 | 153 | 103.2 | –30 | 107.5 | –66 | 124.8 | –187 | 43.0 | –212 | 146.3 | –298 |

| Jordan | 99.6 | 0 | 119.6 | –2 | 124.6 | –3 | 144.5 | –4 | 49.8 | –5 | 169.4 | –6 |

| Kazakhstan | 105.1 | –2 | 126.1 | –9 | 131.4 | –11 | 152.4 | –15 | 52.6 | –16 | 178.7 | –20 |

| Kuwait | 83.3 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 104.1 | 0 | 120.8 | –1 | 41.7 | –1 | 141.6 | –1 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 23.8 | 6 | 28.6 | 5 | 29.8 | 5 | 34.5 | 4 | 11.9 | 4 | 40.5 | 3 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 20.1 | 8 | 24.2 | 6 | 25.2 | 6 | 29.2 | 5 | 10.1 | 5 | 34.3 | 4 |

| Lebanon | 106.0 | –1 | 127.2 | –5 | 132.5 | –6 | 153.8 | –8 | 53.0 | –9 | 180.3 | –10 |

| Macao | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Malaysia | 95.2 | 3 | 114.3 | –7 | 119.0 | –9 | 138.1 | –15 | 47.6 | –16 | 161.9 | –21 |

| Maldives | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mongolia | 68.6 | 2 | 82.3 | 1 | 85.7 | 1 | 99.4 | 0 | 34.3 | 0 | 116.5 | –1 |

| Myanmar | 23.7 | 68 | 28.4 | 53 | 29.6 | 50 | 34.4 | 40 | 11.9 | 38 | 40.3 | 31 |

| Nepal | 21.0 | 26 | 25.2 | 21 | 26.3 | 20 | 30.5 | 16 | 10.5 | 15 | 35.7 | 13 |

| Oman | 45.2 | 2 | 54.3 | 2 | 56.6 | 2 | 65.6 | 1 | 22.6 | 1 | 76.9 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 25.5 | 166 | 30.6 | 129 | 31.9 | 122 | 37.0 | 97 | 12.8 | 92 | 43.4 | 74 |

| Palestine | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Philippines | 28.2 | 130 | 33.9 | 100 | 35.3 | 94 | 40.9 | 74 | 14.1 | 69 | 48.0 | 55 |

| Qatar | 174.7 | –1 | 209.7 | –2 | 218.4 | –2 | 253.4 | –2 | 87.4 | –2 | 297.0 | –2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 99.3 | 0 | 119.2 | –5 | 124.1 | –6 | 144.0 | –10 | 49.6 | –11 | 168.8 | –13 |

| Singapore | 66.3 | 12 | 79.6 | 6 | 82.9 | 5 | 96.2 | 1 | 33.2 | 0 | 112.7 | –3 |

| South Korea | 45.2 | 194 | 54.2 | 135 | 56.5 | 123 | 65.5 | 84 | 22.6 | 76 | 76.8 | 48 |

| Sri Lanka | 53.8 | 14 | 64.6 | 9 | 67.3 | 8 | 78.1 | 4 | 26.9 | 4 | 91.5 | 1 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 23.3 | 23 | 27.9 | 18 | 29.1 | 17 | 33.8 | 14 | 11.6 | 13 | 39.6 | 11 |

| Taiwan | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tajikistan | 13.9 | 6 | 16.6 | 5 | 17.3 | 5 | 20.1 | 4 | 6.9 | 4 | 23.5 | 3 |

| Thailand | 46.5 | 116 | 55.8 | 80 | 58.1 | 73 | 67.4 | 49 | 23.2 | 44 | 79.0 | 27 |

| Timor-Leste | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Turkey | 98.5 | 4 | 118.2 | –41 | 123.1 | –50 | 142.8 | –80 | 49.2 | –86 | 167.4 | –107 |

| Turkmenistan | 93.4 | 0 | 112.1 | –1 | 116.7 | –1 | 135.4 | –2 | 46.7 | –2 | 158.8 | –3 |

| United Arab Emirates | 76.6 | 2 | 92.0 | 0 | 95.8 | 0 | 111.1 | –1 | 38.3 | –1 | 130.3 | –1 |

| Uzbekistan | 21.3 | 26 | 25.6 | 20 | 26.7 | 19 | 30.9 | 16 | 10.7 | 15 | 36.3 | 12 |

| Viet Nam | 17.5 | 174 | 21.0 | 139 | 21.9 | 132 | 25.4 | 109 | 8.8 | 104 | 29.8 | 87 |

| Yemen | 5.9 | 16 | 7.0 | 13 | 7.3 | 13 | 8.5 | 11 | 2.9 | 10 | 10.0 | 9 |

Abbreviations: HFRT = hypofractionated radiation therapy; NA = not available as either data for cancer incidence from Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) or for TRT units from DIrectory of Radiotherapy Centers (DIRAC), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), or both were not available; RT = radiation therapy; SFRT = standard fractionated radiation therapy; TRT = teleradiotherapy units.

Effect of various strategies to maximize the RT infrastructure utilization

The percent of RT accessibility and the need for additional TRT units could change if the number of patients treated/TRT unit/y could be increased beyond the standard 500 patients/TRT unit/y. Using mild to moderate HFRT alone within the 8-hour working schedule of a department, the mean percent of RT accessibility could increase to 74.9% (range, 5.2%-209.7%), while the total additional TRT unit requirements could fall to 4646 units. The reduction in overall treatment time by 1 week would increase both BEDs (early and late) for all the corresponding HFRT schedules compared with SFRT (Table E1). The ratios of BEDs for HFRT versus SFRT would vary from 1.00 to 1.10 for BED (early) and BED (late) (Table E1).

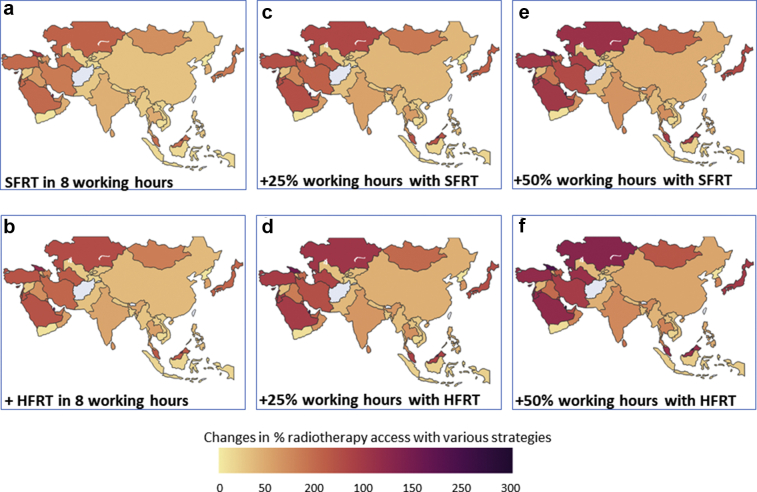

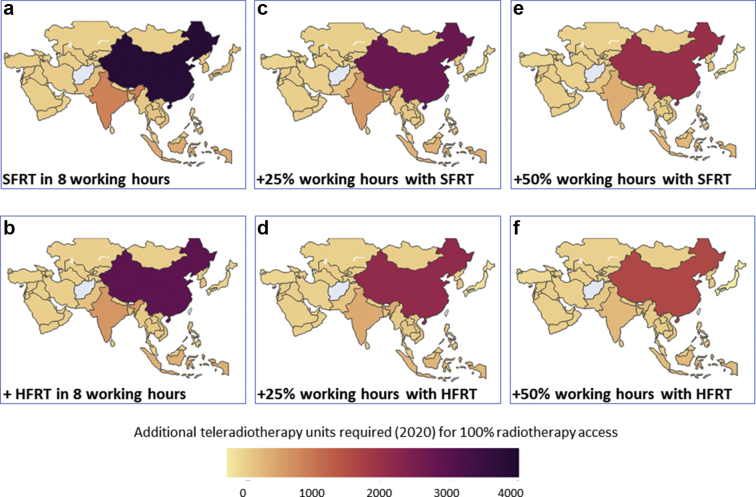

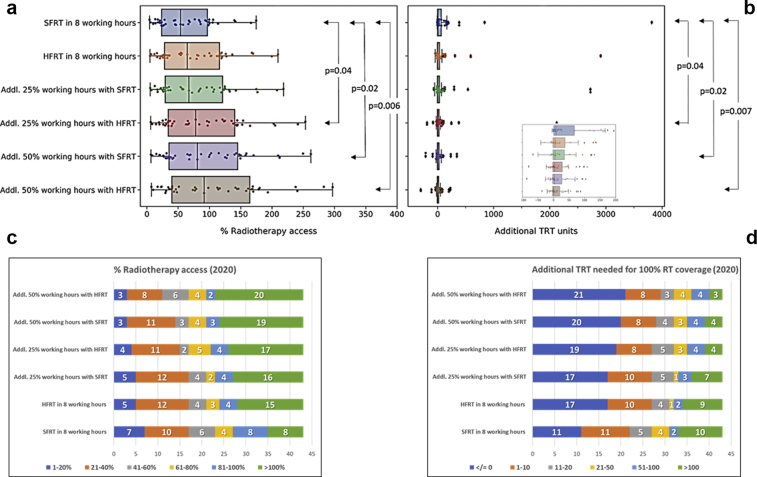

By increasing the working hours with or without HFRT, an improved percent of RT accessibility and a corresponding reduction in additional TRT units needed could be achieved. Thus, the mean percent of RT accessibility would improve to 78% (range, 5.4%-218.4%), 90.5% (range, 6.2%-253.4%), 93.7% (range, 6.4%-262.1%), and 106.2% (range, 7.3%-297%) with additional 25% working hours with SFRT, additional 25% working hours with HFRT, additional 50% working hours with SFRT, and additional 50% working hours with HFRT, respectively (Fig 1, Table 2). Correspondingly, the requirement for additional TRT units to achieve 100% RT access in 2020 with these options would reduce to 4284, 3073, 2820, and 1958 (Fig 2, Table 2). In view of the gross heterogeneity in the existing percent of RT accessibility and the additional TRT required by each of the 43 target countries, a great deal of variability is observed. However, the improvements are significantly better with additional 25% working hours with HFRT (P = .04), additional 50% working hours with SFRT (P = .02), and additional 25% working hours with HFRT (P = .006 for percent of RT accessibility; P = .007 for additional TRT units) compared with SFRT with 8 working hours. HFRT alone does not significantly improve RT accessibility (Fig 3a,b).

Figure 1.

Changes in % radiation therapy (RT) access with various strategies in Asia: (a) with standard fractionated RT (SFRT) in routine working hours of 8 hours/d, (b) with hypofractionated RT (HFRT) within routine hours, (c) with 25% additional working hours (+2 hours) and SFRT, (d) with 25% additional working hours (+2 hours) and HFRT, (e) with 50% additional working hours (+4 hours) and SFRT, (f) with 50% additional working hours (+4 hours) and HFRT. A gradual gain in percent of RT access is observed from (a) to (f).

Table 2.

Effect of various strategies to maximize infrastructure utilization in terms of percent RT access and additional megavoltage teleradiotherapy units required by various countries in Asia for 2020

| Parameters | All Asian countries∗,† |

Low- and middle-income countries∗,† |

High-income countries∗,† |

Unclassified countries∗,† |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean | Range |

Total | Mean | Range |

Total | Mean | Range |

Total | Mean | Range |

|||||

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |||||||||

| Patients with cancer | 9.08M | 0.19M | 457 | 4.51M | 7.56M | 0.24M | 457 | 4.51M | 1.30M | 0.10M | 993 | 0.90M | 0.21M | 0.05M | 14073 | 0.11M |

| Patients requiring RT | 5.49M | 0.11M | 276 | 2.73M | 4.57M | 0.14M | 276 | 2.73M | 0.78M | 0.06M | 601 | 0.54M | 0.13M | 0.03M | 8514 | 0.07M |

| SFRT (8 h/d) | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 62.4 | 4.3 | 174.7 | - | 50.6 | 10.1 | 139.9 | - | 99.8% | 45.2 | 174.7 | - | 29.6 | 4.3 | 85.0 |

| Total TRT required | 10,965 | 255 | 1 | 5462 | 9130 | 338.15 | 7 | 5462 | 1576 | 131.3 | 1 | 1095 | 259 | 64.7 | 17 | 142 |

| Additional TRT required | 6474 | 150.5 | –5 | 3818 | 5987 | 221.7 | –5 | 3818 | 360 | 30.0 | –1 | 194 | 127 | 31.7 | 16 | 67 |

| With HFRT in routine working schedule of 8 hours | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 74.9 | 5.2 | 209.7 | - | 60.8 | 12.1 | 167.9 | - | 119.8 | 54.2 | 209.7 | - | 35.5 | 5.2 | 102.1 |

| Total TRT required | 9139 | 212.5 | 1 | 4552 | 7610 | 281.8 | 6 | 4552 | 1313 | 109.4 | 1 | 912 | 216 | 54.0 | 14 | 119 |

| Additional TRT required | 4646 | 108.0 | –41 | 2908 | 4466 | 165.4 | –41 | 2908 | 96 | 8.0 | –30 | 135 | 84 | 21.0 | –2 | 55 |

| With 25% additional working hours and SFRT | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 78.0 | 5.4 | 218.4 | - | 63.3 | 12.6 | 174.9 | - | 124.8 | 56.5 | 218.4 | - | 37.0 | 5.4 | 106.2 |

| Total TRT required | 8773 | 204.0 | 1 | 4370 | 7305 | 270.5 | 6 | 4370 | 1261 | 105.0 | 1 | 876 | 207 | 51.8 | 14 | 114 |

| Additional TRT required | 4284 | 99.6 | –66 | 2726 | 4163 | 154.1 | –50 | 2726 | 45 | 3.7 | –66 | 123 | 76 | 19.0 | –7 | 53 |

| With 25% additional working hours and HFRT | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 90.5 | 6.2 | 253.4 | - | 73.5 | 14.7 | 202.9 | - | 144.8 | 65.5 | 253.4 | - | 42.9 | 6.2 | 123.2 |

| Total TRT required | 7564 | 175.9 | 1 | 3767 | 6300 | 233.3 | 5 | 3767 | 1085 | 90.4 | 1 | 755 | 179 | 44.7 | 12 | 98 |

| Additional TRT required | 3073 | 71.4 | –187 | 2123 | 3157 | 116.9 | –80 | 2123 | –131 | –10.9 | –187 | 84 | 47 | 11.7 | –23 | 45 |

| With 50% additional working hours and SFRT | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 93.7 | 6.4 | 262.1 | - | 76.0 | 15.2 | 209.9 | - | 149.84 | 67.8 | 262.1 | - | 44.4 | 6.4 | 127.5 |

| Total TRT required | 7311 | 170.0 | 1 | 3642 | 6088 | 225.4 | 5 | 3642 | 1051 | 87.5 | 1 | 730 | 173 | 43.2 | 11 | 95 |

| Additional TRT required | 2820 | 65.5 | –212 | 1998 | 2945 | 109.0 | –86 | 1998 | –166 | –13.8 | –212 | 76 | 41 | 10.2 | –26 | 44 |

| With 50% additional working hours and HFRT | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent RT access | - | 106.1 | 7.3 | 297.0 | - | 86.1 | 17.2 | 237.9 | - | 169.8 | 76.8 | 297 | - | 50.3 | 7.3 | 144.5 |

| Total TRT required | 6451 | 150.0 | 1 | 3213 | 5371 | 198.9 | 4 | 3213 | 927 | 77.2 | 1 | 644 | 153 | 38.1 | 10 | 84 |

| Additional TRT required | 1958 | 45.5 | –298 | 1569 | 2225 | 82.4 | –107 | 1569 | –288 | –24.0 | –298 | 48 | 21 | 5.2 | –37 | 38 |

Abbreviations: HFRT = hypofractionated radiation therapy; M = million; RT = radiation therapy; SFRT = standard fractionated radiation therapy; TRT = teleradiotherapy units.

Data available from various public domains varied - cancer incidence from Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) (n = 47/51); TRT status from DIrectory of Radiotherapy Centres (DIRAC), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) (n = 44/51), and gross national income (GNI)/capita from The World Bank (n = 45/51). Thus, values for patients with cancer and patients requiring RT are for 47 Asian countries, 31 lower-middle-income countries, 12 high-income, and 4 unclassified countries.

Correspondingly, values for percent of RT access, total TRT required, and additional TRT required are for 43 Asian countries, 27 lower-middle-income countries, 12 high-income, and 4 unclassified countries.

Figure 2.

Additional teleradiotherapy units required as per status in 2020 for 100% radiation therapy (RT) access in Asia: (a) with standard fractionated RT (SFRT) in routine working hours of 8 hours/d, (b) with hypofractionated RT (HFRT) within routine hours, (c) with 25% additional working hours (+2 hours) and SFRT, (d) with 25% additional working hours (+2 hours) and HFRT, (e) with 50% additional working hours (+4 hours) and SFRT, (f) with 50% additional working hours (+4 hours) and HFRT. A gradual decline in number of additional teleradiotherapy is observed from (a) to (f).

Figure 3.

(a) Changes in % radiation therapy access for 2020 with various strategies as shown on the X axis. P values indicated are from the Mann-Whitney test for corresponding strategies. (b) Additional teleradiotherapy units required (2020) for 100% radiation therapy access. Insert shows the box plots and scatter after excluding the outliers. P values indicated are from the Mann-Whitney test for corresponding strategies. (c) Changes in the % radiation therapy access in categories of 1% to 20%, 21% to 40%, 41% to 60%, 61% to 80%, 81% to 100%, and >100% in 43 target countries and (d) additional teleradiotherapy units in categories of ≤0, 1 to 10, 11 to 20, 21 to 50, 51 to 100, and >100 in 43 target countries.

Applying these measures, successive improvements in percent of RT accessibility and reductions for additional TRT units for all countries can be observed (Figs 1 and 2). For example, the number of countries that have more than 100% RT coverage with their existing RT infrastructure could increase from 8 to 20 with 50% additional working hours along with HFRT (Fig 3c). Similarly, at present, there are 10 countries that need more than 100 additional TRT units; this number would be lowered to just 3 countries with 50% additional working hours along with HFRT (Fig 3d). Likewise, the number of countries that presently do not need additional TRT units with SFRT delivered in 8 working hours would increase from 11 to 21 with 50% additional working hours along with HFRT (Fig 3d). These changes for individual countries are depicted in Figures E1 and E2.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to result in the deepest global recession in 8 decades with significant contraction of the global economy.3 According to the latest World Economic Outlook published by the International Monetary Fund in June 2020, the global economy is projected to shrink sharply by 4.93% in 2020. It is expected to slowly resume recovery in 2021 as the economic activity may normalize aided by policy support and barring any new crisis.4 However, the risks for even more severe outcomes have not been ruled out and their negative effects could be substantial. A “V” shaped recovery (a steep fall followed by a quick rebound) has been projected for Asia. However, with the continuous and rapid spread of COVID-19 in some Asian countries with high population densities coupled with pre-existing inadequate health care facilities, only partially successful containment measures, the risk of new mutations in severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2, and the lack of a definitive vaccine, the outlook for a fast economic recovery looks grim. Most governments and experts are apprehensive about the dynamics of recovery.23 These adverse factors could have a severe effect on the economic recovery in Asia and might modify the recovery to an “L” shaped recovery, which would be much slower and relatively longer.

Thus, effective policies are needed to forestall the possibility of worse outcomes over an extended period in every sector including health care. Because most of the resources would be directed toward mitigating the contagion and its spread, funding for other areas, especially noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, may be grossly compromised. Pragmatic and cost-effective strategies need to be framed until the green shoots of overall economic recovery are distinctly evident.

The problem would be compounded for the high capital intensive therapeutic modalities, like RT. Presently, with a mean 62.4% RT accessibility, 6474 additional TRT units would be estimated to cost around U.S. $17.2 billion. This is based on the estimates provided by the IAEA of around U.S. $5.3 million for a basic RT center with 2 megavoltage TRT units and other ancillary equipment.14,24 In the post–COVID-19 era, allocation of an amount of this magnitude or even a fraction of it to set up new RT infrastructure appears to be extremely unlikely.

RT dose fractionation schedules are quite variable and are often dictated by the local treatment policies adopted by a particular center, unless the patients are being treated under a specific study protocol.25, 26, 27 However, in contrast to the usual clinical practice of using a higher dose per fraction in Western countries, the usual practice on the Asian continent is to treat patients using standard dose fractionation of 1.8 Gy/fraction in most cases for radical and pre- or postoperative RT. This is because most patients present in locally advanced stages, thereby requiring larger planning target volumes. This, along with poor nutritional status and an adverse hot and humid climate (especially in summer and rainy seasons), contributes to a higher risk of treatment-related morbidity. A conscious effort is therefore required to choose the optimal RT schedule to minimize acute toxicity that could lead to unwarranted treatment interruptions or even dropouts during RT. However, in selected cases, based on the physician's judgment, patients could receive intensive shorter treatment schedules. Thus, a proposal for HFRT needs a cautious approach. The computations carried out in this article have therefore been directed toward a mild to moderate HFRT by proposing to reduce the usual treatment time by just 1 week and keeping the final RT dose the same. For guidance on the BED of these HFRT schedules compared with SFRT, one needs to be aware of the anticipated BED for both early and late effects with the modified HFRT schedules (Table E1).

Thus, to maximize the utilization of the available resources and minimize cost escalation, 5 different strategies have been explored. The mild to moderate HFRT schedules allow a 20% higher number of patients per unit TRT annually. Presently, HFRT has been successfully used in a wide range of disease sites and with similar efficacy without any significant acute or late morbidities, and hence it has been recommended during the COVID-19 pandemic resource constraints.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 The HFRT dose-fractionation schedules could be further adapted depending on the clinical situation, as has been recently jointly proposed for head and neck cancers by the American Society for Radiation Oncology-European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology.36 The BEDs for early and late effects of the mild to moderate HFRT regimes evaluated in the present study are marginally higher than those of SFRT at 2 Gy/fraction and therefore could be safely implemented in routine clinical practice.

Privately owned centers charging for RT services based on the number of fractions may be initially apprehensive that advocating HFRT might reduce their revenue. The RT charges could therefore be tailored based on the treatment package for a specific RT indication rather than on the number of fractions. However, in the longer run, additional patients who would be treated with HFRT might even over compensate the revenue and could be financially rewarding. In state-owned centers, HFRT should not cause a problem as these are usually overburdened with long waiting lists. HFRT could in fact help to reduce their patient waiting period and increase throughput.

Increasing the working hours of the department could also increase the throughput. Even presently, some of the RT centers might be forced to increase their working hours to accommodate the waiting list of patients for RT. This would have to also take into consideration the logistics and the available human resources in each RT center. Surveys reveal that patients are willing to come for RT outside the normal working hours of the department if this could help to reduce their waiting time for initiating RT.37, 38, 39 An additional 50% working hours would need additional personnel or additional financial incentives or compensatory offers to the staff. Further, centers that could run 2 shifts with the same infrastructure could help to generate additional employment for various groups of RT personnel. The cost involved may be a fraction of the investment needed to achieve a similar throughput by establishing additional RT infrastructure. Moreover, in the post–COVID-19 era, job losses are widely anticipated. Recently, qualified RT personnel may therefore face difficulties securing employment owing to lack of demand as new RT infrastructure may be held in limbo during the post–COVID-19 period. Thus, extended working hours could also help to gainfully employ additional skilled workforce if they are available. This could create an overall “win-win” situation for patients, personnel, establishment, and the country.

The benchmark for computing RT accessibility was carried out using 500 patients who could be treated by conventional and relatively simple RT techniques. However, for complicated procedures, the number would be reduced depending on the proportion of such patients being treated in a RT center. By adopting the various options discussed, nearly half of the centers (20/43) would have more than 100% access (Fig 3c). This would allow these centers to also practice specialized RT techniques, like intensity-modulated RT, image-guided RT, respiratory gated procedures, or stereotactic RT procedures. These would take more time for setting up, quality assurance, and execution. Thus, by implementing HFRT and additional working hours, a department could allocate the RT procedures that they would like to practice depending on the type of patients and treatment policies of a particular center. These have to be decided at individual departmental levels taking into consideration their existing infrastructure, available time, and personnel.

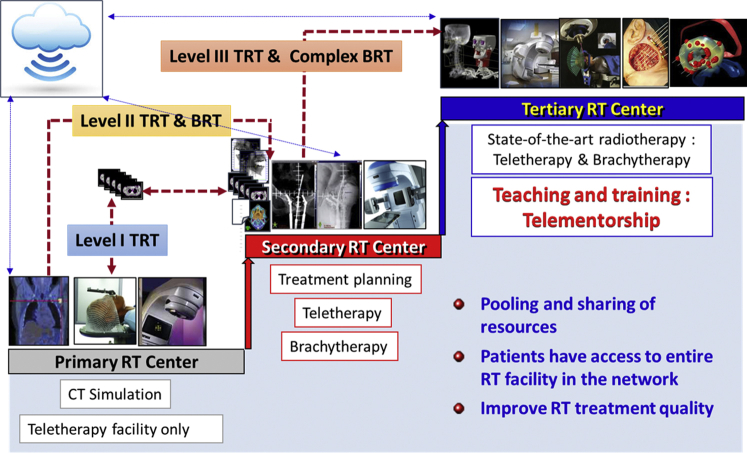

Another potentially beneficial approach could be to pool and share the available resources within a country or subregion.6,11,40, 41, 42 The widespread availability of telecommunication technology provides an opportunity for building a 3-tier teleradiotherapy network by creating primary, secondary, and tertiary RT centers (Fig 4). Although the primary RT center could only execute TRT, the secondary centers could have BRT in addition to teletherapy. The tertiary centers could have the state-of-the-art RT facilities and be responsible for coordinating teaching and training for all the subsidiary centers within the network. Patients, if needed, could be referred to a higher center for specialized treatments. The tertiary centers would also be the focal point for framing national and regional guidelines to provide uniformity and quality in cancer care. This would allow pooling and sharing of resources, give access to the entire range of RT facilities, and improve the quality of RT.6,11,41,42 This approach is also cost-effective and could provide substantial positive returns on investment.6,9 The 3-tier teleradiotherapy network could be further integrated as a part of a teleoncology network and could include teleradiodiagnostics, telepathology, tele-education with capacity building, teleconsultation, and telefollow-up.43, 44, 45, 46 This may not only be an effective means to improve cancer care in many countries but may also be cost-effective, economically viable, and a convenient means for optimizing cancer care during the present pandemic through maximal resource utilization and cost minimization.

Figure 4.

A schematic representation of a 3-tier teleradiotherapy network integrating primary, secondary, and tertiary radiation therapy centers to pool and share the resources, enabling patients to have access to the entire radiation therapy infrastructure within the network.

Certain limitations of these estimates need to be considered. The computations presented here are based on the data of RT infrastructure as available in the DIRAC database of IAEA at the time of writing.19 This is a voluntary registration site and every center is expected to update their status on a regular basis. Thus, the figures shown here are dynamic and could change over time. Moreover, the details of the human resources are not available in DIRAC or any other public domain. These need to be checked at the level of individual RT centers. The estimates of percent of RT accessibility and additional TRT units have not considered the availability of particle therapy, as these are used for specific and highly selective patients. Similarly, although BRT forms an important component of RT, its use depends on the patient’s type of cancer and local treatment policies and guidelines. Thus, the number of BRT units also have not been a part of these computations. The requirement of BRT units could be assessed by individual countries based on the IAEA recommendations of 1 high-dose rate BRT unit/200 patients.14 Furthermore, the patient percentage and the dose schedules that have been considered for computing the additional patients who could be treated with HFRT are a suggestive template. These figures could vary and should be computed by individual RT centers based on their local clinical practice. In addition, solutions proposed would depend on the availability of personnel and hence may not be applicable worldwide, especially in high-income countries in Western Europe and North America that may not be facing the problem of lack of RT infrastructure to the same extent as in Asia. Moreover, the outcomes with the proposed HFRT schedules require close monitoring for their therapeutic effectiveness in different sites compared with standard fractionation schedules.

The present pandemic certainly possesses immense challenges in providing adequate RT access to patients, especially as the global economy is undergoing a deep and unprecedented plunge. One-size-fits-all may not be applicable to all countries. Individual centers and countries need to frame out pragmatic strategies to allow maximal resource utilization without cost escalation until such time that a steady economic recovery takes place and the situation normalizes. The challenges also open up new opportunities for improvements in cancer care and treatment as discussed.

The strategies presented here could be applicable to any center and could enhance cancer care capability not only in Asia but also in any other region, thereby providing a cost-effective solution with additional returns on investment.6 However, these opportunities need to be individualized based on the available RT infrastructure, human resources, prevalent types of cancer, treatment guidelines, practices, and associated logistics. Collectively, even in the present adverse conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, these cost-effective measures could provide pragmatic solutions to help move toward meeting the targets of the UN 2030 Agenda as defined by the SDGs, in particular SDG 3, related to good health and wellbeing.47 One of the targets of SDG 3 is to reduce by one-third the premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases (including cancer) by 2030. Achieving this, especially in the post–COVID-19 era, is challenging and calls for a unified and determined action from all stakeholders to pool their resources and explore realistic and practical solutions for maximal utilization of existing infrastructure and human resources.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Indranil Pan, PhD, Research Fellow, Imperial College London and Group Leader, The Alan Turing Institute, London, for his support and guidance for programming in Python for data analysis and generating outputs.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: There are no actual or potential conflicts of interest to declare.

All data used in this study have been extracted from the public domain sites of the various organizations as detailed in the text and cited in the references. The summary of these are listed in Table E2. These can be accessed freely.

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adro.2020.09.005.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.United Nations Industrial Devlopment Organization Coronavirus: The economic impact – 26 May 2020. 2020. https://www.unido.org/stories/coronavirus-economic-impact-26-may-2020 Available at:

- 2.Statista . Erin Duffin; 2020. Impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the global economy.https://www.statista.com/topics/6139/covid-19-impact-on-the-global-economy/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Bank 2020 . World Bank; Washington, D.C.: 2020. Global economic prospects, June 2020.https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Monetary Fund World economic outlook, April 2020: The great lockdown. 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020#Introduction Available at:

- 5.United Nations Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf Available at:

- 6.Datta N.R., Rogers S., Bodis S. Challenges and opportunities to realize “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” by the United Nations: Implications for radiation therapy infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105:918–933. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) Cancer tomorrow. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/graphic-isotype?type=0&type_sex=0&mode=population&sex=0&populations=900&cancers=39&age_group=value&apc_male=0&apc_female=0&single_unit=500000&print=0 Available at:

- 8.Atun R., Jaffray D.A., Barton M.B. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1153–1186. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datta N.R., Samiei M., Bodis S. Are state-sponsored new radiation therapy facilities economically viable in low- and middle-income countries? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samiei M. Challenges of making radiotherapy services accessible in developing countries in cancer control 2013, global health dynamics in association with International Network for Cancer Treatment and Research (INCTR). 25 Sep 2013. http://cancercontrol.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/cc2013_83-96-Samiei-varian-tpage-incld-T-page_2012.pdf Available at: Accessed October 11, 2020.

- 11.Datta N.R., Samiei M., Bodis S. Radiation therapy infrastructure and human resources in low- and middle-income countries: Present status and projections for 2020. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta N.R., Samiei M., Bodis S. Radiotherapy infrastructure and human resources in Europe - present status and its implications for 2020. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:2735–2743. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenblatt E., Fidarova E., Zubizarreta E.H. Radiotherapy utilization in developing countries: An IAEA study. Radiother Oncol. 2018;128:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenblatt E., Zubizarreta E. International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna, Austria: 2017. Radiotherapy in cancer care: Facing the global challenge.https://www-pub.iaea.org/books/iaeabooks/10627/Radiotherapy-in-Cancer-Care-Facing-the-Global-Challenge Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel-Wahab M., Fidarova E., Polo A. Global access to radiotherapy in low- and middle-income countries. Clin Oncol. 2017;29:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Wahab M., Lahoupe B., Polo A. Assessment of cancer control capacity and readiness: The role of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e587–e594. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30372-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs World population prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ Available at:

- 18.The World Bank WV.1 World development indicators: Size of economy. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Available at:

- 19.International Atomic Energy Agency DIRAC (DIrectory of RAdiotherapy Centres) https://dirac.iaea.org/Data/CountriesLight Available at:

- 20.Chow R., Hoskin P., Schild S.E. Single vs multiple fraction palliative radiation therapy for bone metastases: Cumulative meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol. 2019;141:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler J.F. 21 years of biologically effective dose. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:554–568. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31372149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The World Bank World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups Available at:

- 23.Wignaraja G. International Monetary Fund predictions: Asia’s growth after Covid-19. https://www.odi.org/blogs/16925-international-monetary-fund-predictions-asia-s-growth-after-covid-19 Available at:

- 24.International Atomic Energy Agency . International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna, Austria: 2010. IAEA Human Health Series Nos.14, Planning national radiotherapy services: A practical tool.https://www-pub.iaea.org/books/iaeabooks/8419/Planning-National-Radiotherapy-Services-A-Practical-Tool Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barton M.B., Jacob S., Wong K.H.W. Review of optimal radiotherapy utilisation rates: Collaboration for cancer outcomes research and evaluation. 2013. https://inghaminstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/RTU-Review-Final-v3-02042013.compressed.pdf Available at: Accessed October 11, 2020.

- 26.Williams M.V., James N.D., Summers E.T., Barrett A., Ash D.V. National survey of radiotherapy fractionation practice in 2003. Clin Oncol. 2006;18:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yahya N., Roslan N. Estimating radiotherapy demands in South East Asia countries in 2025 and 2035 using evidence-based optimal radiotherapy fractions. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2018;14:e543–e547. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaorsky N.G., Yu J.B., McBride S.M. Prostate cancer radiotherapy recommendations in response to COVID-19. 2020. Available at: [DOI]

- 29.Mendez L.C., Raziee H., Davidson M. Should we embrace hypofractionated radiotherapy for cervical cancer? A technical note on management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiother Oncol. 2020;148:270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang S.H., O'Sullivan B., Su J. Hypofractionated radiotherapy alone with 2.4 Gy per fraction for head and neck cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Princess Margaret experience and proposal. 2020. Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Guckenberger M., Belka C., Bezjak A. Practice recommendations for lung cancer radiotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ESTRO-ASTRO consensus statement. Radiother Oncol. 2020;146:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braunstein LZ, Gillespie EF, Hong L, et al. Breast radiotherapy under COVID-19 pandemic resource constraints — approaches to defer or shorten treatment from a Comprehensive Cancer Center in the United States. 2020;5:582-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Benson R, Prashanth G, Mallick S. Moderate hypofractionation for early laryngeal cancer improves local control: A systematic review and meta-analysis [E-pub ahead of print]. 2020. 10.1007/s00405-020-06082-9. Accessed June 15, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Achard V., Aebersold D.M., Said Allal A. A national survey on radiation oncology patterns of practice in Switzerland during the COVID-19 pandemic: Present changes and future perspectives. Radiother Oncol. 2020;150:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang S.L., Fang H., Song Y.W. Hypofractionated versus conventional fractionated postmastectomy radiotherapy for patients with high-risk breast cancer: A randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:352–360. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomson D.J., Palma D., Guckenberger M. Practice recommendations for risk-adapted head and neck cancer radiation therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: An ASTRO-ESTRO consensus statement. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown A.M., Atyeo J., Field N. Evaluation of patient preferences towards treatment during extended hours for patients receiving radiation therapy for the treatment of cancer: A time trade-off study. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calman F., White L., Beckingham E., Deehan C. When would you like to be treated?—A short survey of radiotherapy outpatients. Clin Oncol. 2008;20:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White L., Beckingham E., Calman F., Deehan C. Extended hours working in radiotherapy in the UK. Clin Oncol. 2007;19:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.01.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Datta N.R., Heuser M., Bodis S. A roadmap and cost implications of establishing comprehensive cancer care using a teleradiotherapy network in a group of sub-Saharan African countries with no access to radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;95:1334–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Datta N.R., Heuser M., Samiei M. Teleradiotherapy network: Applications and feasibility for providing cost-effective comprehensive radiotherapy care in low- and middle-income group countries for cancer patients. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:523–532. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Datta N.R., Rajasekar D. Improvement of radiotherapy facilities in developing countries: A three-tier system with a teleradiotherapy network. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:695–698. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sabesan S. Medical models of teleoncology: Current status and future directions. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10:200–204. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shirke M.M., Shaikh S.A., Harky A. Tele-oncology in the COVID-19 Era: The way forward? Trends Cancer. 2020;6:547–549. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sirintrapun S.J., Lopez A.M. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540–545. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_200141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thaker D.A., Monypenny R., Olver I., Sabesan S. Cost savings from a telemedicine model of care in northern Queensland, Australia. Med J Aust. 2013;199:414–417. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization Sustainable development goals- the goals within a goal: Health targets for SDG-3. https://www.who.int/sdg/targets/en/ Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.