ABSTRACT

Gain-of-function (GOF) p53 mutations occur commonly in human cancer and lead to both loss of p53 tumor suppressor function and acquisition of aggressive cancer phenotypes. The oncogenicity of GOF mutant p53 is highly related to its abnormal protein stability relative to wild type p53, and overall stoichiometric excess. We provide an overview of the mechanisms of dysfunction and abnormal stability of GOF p53 specifically in lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, where, depending on histologic subtype, 33-90% of tumors exhibit GOF p53 mutations. As a distinguishing feature and oncogenic mechanism in lung and many other cancers, GOF p53 represents an appealing and cancer-specific therapeutic target. We review preclinical evidence demonstrating paradoxical depletion of GOF p53 by proteasome inhibitors, as well as preclinical and clinical studies of proteasome inhibition in lung cancer. Finally, we provide a rationale for a reexamination of proteasome inhibition in lung cancer, focusing on tumors expressing GOF p53 alleles.

KEYWORDS: P53 mutation, gain-of-function, stability, proteasome, proteasome inhibitors, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide.1 In the United States alone, the estimated incidence of lung cancer is 228,115 cases for the year 2019, second only to breast cancer and prostate cancer in women and men respectively.2 Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer deaths for both men and women with an estimated 142,670 deaths in the US alone for the year 2019, accounting for almost 25 percent of all cancer deaths.2 One in 15 males and one in 17 females in the United States will be diagnosed with lung cancer in their lifetime.2

Notably, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was the first human cancer for which therapy targeted at oncogenic driver mutations was pioneered,3 and subsequently numerous additional targeted agents were developed for rare targetable subtypes of NSCLC, along with the more recent establishment of immune checkpoint therapy for a subset of lung cancer patients.4,5 Nevertheless, the poor prognosis associated with lung cancer remains, due to a lack of targeted and immune therapeutic approaches for the majority of patients. Among genetic driver gene mutations in lung cancer, p53 is mutated in 33 to 90 percent of tumors, depending on histologic subtype,6 and mutant p53 is implicated in driving many of the hallmarks of cancer that lead to cancer progression and poorer prognosis.7–9 One distinguishing characteristic of mutant p53, in contrast to wild type p53, is its high stability and massive accumulation, as it is well known to evade degradation by the proteasome protein degradation machinery. Cancer cells harboring mutant p53 depend on the excess level of the protein to drive oncogenic activities, including proliferation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis and resistance to therapy.10,11 Therefore, much research effort has been devoted to uncovering means of degrading mutant p53. However, to date, there are no FDA approved drugs that primarily target this pathway, although some drug candidates are currently under investigation in clinical trials.12,13

There is emerging preclinical evidence of paradoxical degradation of mutant p53 by prolonged exposure to proteasome inhibitors.14–16 Recent reports have also established evidence of proteasomal hyperactivity in mutant p53 bearing cancer cells but not in wild type p53 cancers.17,18 Proteasome inhibitors are currently FDA approved for the treatment of myeloma and are relatively well tolerated. Therefore, these observations provide an attractive insight into the possibility that proteasome inhibitors can be used to target cancers with mutant p53, of which lung cancer is one. However, clinical trials of proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer, or any other cancer, have not selected patients based on p53 mutation status and unfortunately, did not live up to expectations. Given these considerations, a rational approach to patient selection and synergistically appropriate combinatorial therapeutic regimen with proteasome inhibitors may have profound therapeutic implications, and warrants a closer attention for use in lung cancer.

Physiologic p53 function, structure and regulation

p53 is a nuclear protein, transcription factor, and tumor suppressor that responds to many cancer-related cellular stressors including DNA damage, oncogene signaling and metabolic dysregulation, whose function is to induce cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, DNA repair and alter metabolism in response to these cellular stressors.19 Alterations in p53 function occurs in most cancers through genetic loss at the p53 locus, losses within the p53 tumor suppressor network of other upstream regulators or downstream targets of p53, or through missense p53 mutations which result in gain-of-function (GOF) oncogenic activities.20

The p53 protein consists of five functional domains. The N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD; residues 1–93) is an intrinsically disordered domain responsible for interacting with transcriptional activators.21 Adjacent is the proline rich domain (PRP; residues 94–101) which enables protein-protein interactions.22 A structured DNA binding domain (DBD; residues 102–292) follows the PRP, and is responsible for recognizing and binding to promoters of target genes.23 The tetramerization domain lies between residues 324–355 and allows p53 to form tetramers that are required for p53 DNA binding activity and thus, tumor suppressor activity.24 Finally, the intrinsically disordered C-terminal domain (CTD; residues 360–393) represents an interaction site for many proteins, and regulates the sequence-specific DNA binding activity of p53.25

Under normal unstressed cellular conditions, p53 is located in the nucleus where it is closely associated with its major negative regulator, the E3 Ligase, Murine Double Minute 2 (MDM2). MDM2 maintains p53 in an inactive state and regulates physiologic p53 levels in unstressed cells by orchestrating a series of ubiquitination events that results in degradation of p53 by the ubiquitin/proteasome system.26–29 Upon cellular stress, p53 becomes activated by a multistep process of phosphorylation at the N-terminal TAD by kinases such as ATM/ATR and CHK2/CHK1.30–34 These phosphorylation events result in conformational changes in p53 that decrease its affinity for MDM2, thus decreasing p53 ubiquitination and causing stabilization.35 At the same time, p53 also forms a tighter association with its transcriptional coactivators p300 and CREB-binding protein (CBP), resulting in acetylation and further stabilization.36,37 The attained stable levels of p53 under these conditions is sufficient to activate its target genes in order to bring about cellular responses to stress, including cell cycle arrest, DNA damage repair, apoptosis and senescence.38 p53 also transactivates MDM2, such that when stress is overcome, p53, in turn, is quickly inactivated by MDM2-driven ubiquitination in a negative feedback loop to maintain homeostasis.39 Indeed, this is the overarching model of p53 regulation. More recently, additional important regulators have emerged, and include other E3 ligases with the ability to ubiquitinate p53, such as COP1, PIRH2, TRIM24, and the chaperone-associated hsc70 interacting protein (CHIP).40–42 Another critically important regulator of p53 is murine double minute 4 (MDM4; also known as MDM-x) which does not impact p53 stability, but negatively regulates its activity by occluding the p53 N-terminal TAD.43,44 MicroRNAs (miRNA) have also been implicated in p53 regulation either directly by targeting p53 mRNA, or indirectly, by targeting the mRNA of its key regulators including MDM2 and MDM4, p85-alpha, CDC42, SIRT1, HDAC, and mTOR.45–48

Aberrant p53 function and regulation

During oncogenesis, the loss of normal p53 tumor suppressor function occurs either through alterations in p53 regulation or structure. Regulatory malfunction occurs primarily through overexpression or amplification of its major negative regulators including MDM2, MDM4, COP1, and PIRH2. Alterations in MDM2 regulators that increase MDM2’s activity including ARF silencing, HAUSP overexpression, and WIP1 amplification have also been described as a means of wildtype p53 suppression in select tumors.40

Structural abnormalities leading to loss of p53 function occur primarily through mutations. p53 mutations occur in about 50 percent of human cancers.19,49 Broadly, these mutations are either somatic or germline. Germline mutations in p53 are characterized in familial syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, which is known to predispose to several cancer types.50,51 Somatic mutations are more frequent.52 They include missense mutations within the DNA-binding domain, frameshift insertions and deletions, nonsense mutations and silent mutations. Of these, missense mutations are most common, representing 75% of all p53 mutations and are present in 40% of all human cancers.49 Other mutations occur less frequently with frameshift insertions and deletions, nonsense mutations and silent mutations accounting for 9, 7, and 5% of all p53 mutations respectively.53

p53 mutations in lung cancer

p53 mutations occur in the majority of lung cancers, ranging from 33% in adenocarcinomas, to 79% in squamous cell cancer, and up to 90% in small cell lung cancer.6 Mutant GOF p53 is now recognized as a driver oncogene in lung carcinogenesis, and p53 missense mutations are closely related to smoking.49,52,53 Mutant p53 has been implicated in nearly all 10 hallmarks of cancer, including proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, genomic instability and altered metabolism (Figure 1).7–9 Indeed loss of p53 tumor suppressor function and GOF oncogenic activities may portend a poorer prognosis in lung cancer.54–58 As a result, mutant p53 is considered an attractive target for lung cancer therapy; however to date, there are no FDA-approved drugs that primarily target this pathway in lung or any other cancer. However, promising candidate therapeutics that indirectly target GOF p53, such as APR-246 and HSP90 inhibitors, have recently entered clinical testing.12,13 While eagerly awaiting the results of these trials, efforts continue toward discovering novel targetable vulnerabilities of mutant p53. One such potential vulnerability of GOF p53-expressing lung cancers is the altered proteasome homeostasis induced by GOF p53, and the possibility that GOF p53-induced proteasome dysregulation could be targeted by proteasome inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Wildtype p53 is a tumor suppressor while mutant p53 acquires gain-of-function (GOF) oncogenic activities implicated in several hallmarks of cancer.

Crosstalk between mutant p53 and the proteasome machinery

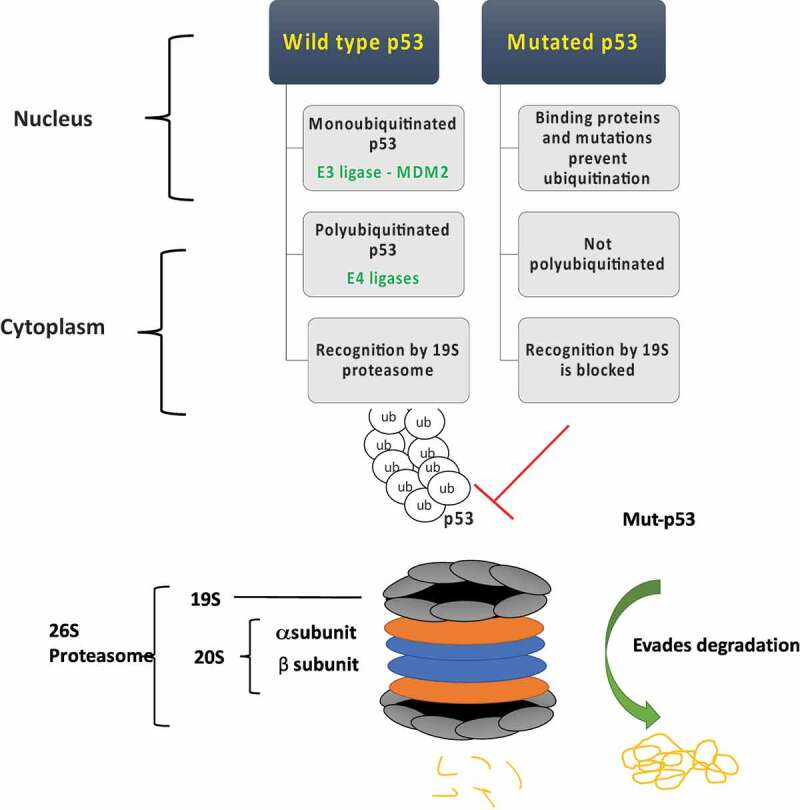

The proteasome is a multi-subunit/multi-complex catalytic system comprised of the 20S catalytic core and the 19S regulatory particle, which together form the 26S proteasome (Figure 2). The proteasome is the key degradation apparatus responsible for maintaining protein homeostasis in eukaryotes through chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and caspase-like activities.59–61 The 19S regulatory particle caps the 20S proteasome on both ends, and acts as an external gate through which proteins must first be processed before degradation. The 19S particle is responsible for identifying proteins tagged by ubiquitination, deubiquitinating these proteins and guiding them into the 20S core. The 20S core consists of two external alpha subunit rings, and two inner beta subunit rings, with each ring made up of seven subunits. It is within the 20S proteasome that proteins already processed by the 19S are degraded in an ATP-dependent manner via chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and caspase-like activities.

Figure 2.

Wild type p53 is readily degraded by the proteasome through a multistep process of ubiquitination mediated primarily through the E3 ligase Murine Double Minute 2 (MDM2) and other E4 ligases. Mutant p53 (Mut-p53) evades proteasomal degradation likely due to defective ubiquitination and recognition by the proteasome machinery.

The maintenance of high levels of mutant p53 in cancer cells is critical to its GOF oncogenic activities.10,11 Indeed, lung and other cancers are “addicted” to this stoichiometric excess of mutant p53 for survival.62 As discussed previously, and shown in Figure 2, wild type p53 is tightly regulated and readily degraded by the proteasome. Mutant p53 on the other hand, is known to evade this degradation machinery, accounting for its massive accumulation and high stability. Much effort has gone into understanding the mechanism by which mutant p53 evades degradation by the proteasome. One of the first proposed and generally accepted mechanisms is decreased binding of mutant p53 by MDM2 and the resulting insufficient ubiquitination of p53 mutants for downstream degradation.63,64 On the other hand, the inability of mutant p53 to bind MDM2 for transactivation leads to constitutionally low levels of MDM2 in most tumors with mutant p53, abrogating the negative feedback loop seen under wild type p53 conditions.

While the effects of p53 missense mutations on MDM2 binding and MDM2 transactivation may, in fact, be present in many tumors with mutant p53, conformational change does not fully explain the aberrant stability of mutant p53. It is now known that some p53 mutants retain their conformation but still attain high stability and accumulation.65 Further advances in knowledge have demonstrated that MDM2 binds mutant p53 and vice versa, however, ubiquitination and degradation of mutant p53 is less efficient.41,66–69 More recent data now highlights previously published findings suggesting that certain proteins, including the heat shock family of proteins, form stable complexes with mutated p53, protecting it from ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome.70–73. On the other hand, some heat shock proteins bind mutant p53, aiding in chaperone mediated degradation by the E3 ligase CHIP.74,75 Additional data has also implicated macroautophagy as a mechanism of mutant p53 degradation following prolonged proteasome inhibition.16 Still other work from this laboratory has suggested that DNA damage signals that normally stabilize wild-type p53, can occur constitutively in lung cancer cells and induce stabilization of mutant p53, inducing GOF oncogenic activity as opposed to activities related to wild-type p53 driven DNA repair, growth arrest, or apoptotic activities.76 Together, these findings suggest that factors specific to cancer cells or within the tumor microenvironment may be at play in the stabilization of mutant p53.

Recent analyses of several GOF-p53 cancer cell lines have also shown differential upregulation of the 20S/26S proteasome/immunoproteasome subunit genes in the setting of GOF p53 mutations across many cancer types.17,77 Using single cell proteomic analysis and RNA-sequencing, the authors initially analyzed a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell line with mutant p53 before and after p53 depletion. Genes belonging to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway were the most significantly affected genes.17 They further evaluated four other TNBC cell lines and confirmed similar findings. Remarkably, they also found a significant decrease in proteasome activity upon silencing of mutant p53 in cell lines of many different cancer types including ovarian, pancreatic, hepatic, colonic and prostate cancers. Indeed, depletion of mutant p53, but not wild type p53, resulted in decreased activity of the rate limiting chymotrypsin-like and trypsin-like activities of the proteasome, which was linked to the ability of mutant p53 to transactivate the proteasome family of genes.17 Interestingly, a prior study of lung and colon cancer cell lines expressing wildtype and mutant p53, respectively, showed suppression of proteasomal activity with wild type p53 expression, while increased proteasomal activity was observed in the presence of mutant p53.18

As already noted, p53 is an important regulatory protein whose degradation is dependent on the ubiquitin-proteasome system. As such, inhibition of the proteasome is expected to result in accumulation of p53, which has been reported.78–80 However, published data also reveal that prolonged proteasome inhibition paradoxically results in degradation of mutant p53 through a mechanism yet to be determined.14,15 Indeed, lessons learned from multiple myeloma would suggest that the hyperactive proteasome induced by GOF p53 may contribute to oncogenesis and/or paradoxical stabilization of GOF p53 via rapid preferential degradation of a critical tumor-suppressive regulatory protein involved in p53 turnover. In the case of multiple myeloma, it has been suggested that the hyperactive proteasome degrades the NF-KB inhibitory protein, IκBα, resulting in increased stability of NF-KB oncogene leading to decreased apoptosis and increased cancer cell survival.81–85 Inhibiting the proteasome with a proteasome inhibitor led to IκBα stabilization and subsequent degradation of NF-KB, which in turn, resulted in increased apoptosis and decreased survival. This underscored a mechanism of action of proteasome inhibitors in myeloma, leading to FDA approval of the drug bortezomib. Additionally, the reported degradation of mutant p53 by macroautophagy upon prolonged proteasome inhibition with MG132 could be implicated in the mechanistic pathway of mutant p53 depletion by these agents.16

Use of proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer – from preclinical studies to clinical trials

Despite the evidence of GOF mutant p53 destabilization by the proteasome, to date, no clinical trial of proteasome inhibitors in lung, or any other cancer, has selected patients based on p53 mutation status. Preclinical studies of proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer have shown evidence of efficacy across several cell lines in vitro.86–88 The few published xenograft models also showed evidence of proteasome inhibitor efficacy in lung cancer.86,88,89 Moreover, evidence of antitumor activity in vivo was also demonstrated in other cancer models, including head and neck, pancreatic, prostate and ovarian.90–92 Mechanisms of action were identified to involve several pathways including NF-KB inhibition and subsequent VEGF downregulation, downregulation of the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl-2 and Bcl- XL, wildtype p53 accumulation and p21 upregulation, p27kip upregulation, and upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinases.86,88,93 In addition, combination therapy with currently available chemotherapeutics appeared to be more effective.86,89,91

Unequivocally, phase I studies in lung cancer with bortezomib showed acceptable toxicity with some evidence of activity.94–98 A phase 1 trial of induction therapy with the combination of a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) and bortezomib in 21 patients showed 60% or more histologic tumor necrosis following treatment in 30% of patients, and 90% necrosis in 2 patients.99 Another phase I study of marizomib and HDACi showed evidence of activity resulting in stable disease and tumor shrinkage but did not meet RECIST criteria for response.100

As bortezomib was the first FDA-approved proteasome inhibitor, most clinical trials of proteasome inhibition in lung cancer have utilized bortezomib (see Table 1). Only one study in lung cancer patients of the second generation proteasome inhibitor, carfilzomib, has been reported in the literature, and it was used as a single agent.116 Two studies employing carfilzomib in combination with chemotherapy have also been initiated in lung cancer, but one of those trials, a combination study with carboplatin and etoposide, was terminated early, while the other trial employing carfilzomib is still ongoing, evaluating the combination of carfilzomib with irinotecan in irinotecan-sensitive cancers.117

Table 1.

Phase I/II and II trials of proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer.

| Study | Arms | Assessed Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combination Therapy in Previously Treated Patients | Phase II, previously treated advanced NSCLC, 2006101 |

Arm A Bortezomib on D1,4,8, 11 (n = 75) Arm B Bortezomib on D1,4,8,11 plus Docetaxel D1 (n = 80) |

Response Rate (%): 8 vs 9 Disease Control Rate (%): 29 vs 54 Median PFS (months):1.5 vs 4 One-year survival (%): 39 vs 33 Median survival (months): 7.4 vs 7.8 |

| Phase II, previously treated advanced NSCLC 2009102 |

Arm A Erlotinib D1 (n = 25) Arm B Erlotinib D1 plus Bortezomib D1 and 8 (n = 25) |

Response rate (%):16 vs 9 Median PFS (months): 2.7 vs 1.3 Median OS (months): 7.3 vs 8.5 months 6-month Survival: 56% in both |

|

| Phase II, advanced NSCLC, Performance status of 2, 2009103 |

Arm A Docetaxel on D1, 8, 15 plus Cetuximab loading dose on D1 then weekly maintenance dose (n = 32) Arm B Docetaxel on D1, 8, 15 plus Bortezomib on days 1,8, 15. (n = 32) |

Response Rate (%):13.3 vs 10.3 Median PFS (months):3.4 vs 1.9 months Median OS (months): 5 vs 3.9 |

|

| Phase II, previously treated advanced NSCLC, 2010104 |

Arm A Pemetrexed D1 plus Bortezomib D1 and 8 (n = 45) Arm B Pemetrexed D1 alone (n = 45) Arm C Bortezomib D1 and 8 (n = 40) |

Response rate (%): 7 vs 4 vs 0 Disease control rate (%): 73 vs 62 vs 43 Median survival OS (months): 8.6 vs 12.7 vs 7.8 |

|

| Phase II, previously treated advanced NSCLC, 2011105 |

Arm A Docetaxel D1 plus Bortezomib on D1 and 8 (n = 40) Arm B Docetaxel on D1 then Bortezomib on days 2 and 8 (n = 41) |

Response Rate (%): 10 vs 10 Disease Control Rate (%): 50 vs 49 Median PFS (weeks): 12 vs 11 Median OS (months): 13.3 vs 10.5 |

|

| Phase II, advanced NSCLC as third line therapy, 2014106 |

Single Arm biweekly Bortezomib D1, 4, 8, 11 and daily 2-week Vorinostat (n = 18) |

Response rate: No objective response. Stable disease (%): 27.8 Median PFS (months): 1.5 Median OS (months): 4.7 |

|

| Phase I/II, advanced NSCLC, 2015107 |

Single Arm Bortezomib plus Paclitaxel and carboplatin with concurrent thoracic radiation therapy |

Response rate (%): 26 Median OS (months): 25 Median PFS (months): 8.4 |

|

| Phase II, locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, 2016108 |

Single Arm Bortezomib Plus Gemcitabine/Cisplatin (n = 53) |

Response Rate (%): 17 Median PFS (months): 2.5 Median OS (months): 10.6 1-year survival (%): 38.1 |

|

| Combination Therapy in Chemo-naïve Patients | Phase II, chemo naïve advanced NSCLC, 2009109 |

Single Arm Bortezomib plus Gemcitabine and Carboplatin (n = 114) |

Response Rate (%): 23 Disease Control Rate: 68 Median PFS (months): 5 Median OS (months): 11 1-year survival (%): 47 2-year survival (%): 19 |

| Phase I/II, chemo-naïve advanced NSCLC, 2012110 |

Single Arm Weekly Bortezomib D1 and 8 Plus standard doses of Carboplatin and Bevacizumab (n = 9) |

Response Rate (%): 44 Median PFS (months): 5.5 Median OS (months): 10.9 |

|

| Single Agent Therapy in Chemo-naïve Patients | Phase II, chemo-naïve advanced NSCLC, 2010111 |

Single Arm biweekly Bortezomib Day 1,4,8, 11 every 21 days (n = 14) |

Response Rate (%): No objective response Disease Control Rate (%): 21 Median PFS (months): 1.3 Median OS (months): 9.9 |

| Phase II, chemo-naive advanced NSCLC, 2012112 |

Single Arm Bortezomib on D1 and 4 for 2 weeks followed by 10-day rest period (n = 18) |

Response Rate (%): No objective response Disease Control Rate: 59 Median PFS (months): 2.4 Median OS (months): 9.8 |

|

| Single Agent in Previously Treated Patients | Phase II, relapsed or refractory extensive stage SCLC, 2006113 |

Single Arm Bortezomib (n = 56; 28 platinum sensitive and 28 platinum refractory) |

Response Rate (%): 1 patient Median PFS (months): 1 Median OS (months): 3 |

| Phase II, advanced-stage bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, 2011114 |

Single Arm Biweekly Bortezomib on D1 and 8 (n = 42) |

Response Rate (%): No objective response Disease Control Rate (%): 57 Median PFS (months): 5.5 Median OS (months): 13.6 |

|

| Phase II, KRAS G12D-mutant lung cancers, 2019115 |

Single Arm Biweekly Bortezomib on D1, 4, 8, 11 (n = 16) |

Response Rate (%): 6 Disease Control Rate: 5 patients Median PFS (months): 1 month Median OS (months): 13 |

|

| Phase I/II, Carfilzomib in advanced solid tumors (NSCLC, SCLC, OVCC, RCC, other)116 |

Single Arm 2–10 minute twice weekly infusion of Carfilzomib SCLC (n = 9) NSCLC (n = 15) |

Response Rate (%): 0 Disease Control Rate (%):21.5% Stable Disease: 43.1% after 2 cycles. |

Notably, single agent bortezomib in non-selected patients, whether pre-treated or chemo-naïve, did not show the promising results of preclinical studies. In the single study focusing on advanced refractory extensive stage SCLC patients, one patient with platinum-refractory disease had a partial response to single agent bortezomib.113 Since refractory disease to platinum is associated with mutant p53 status, it would have been interesting to know the p53 status of this particular patient. Another study of advanced-stage bronchioloalveolar carcinoma showed one exceptional responder who had mucinous adenocarcinoma; however, this study was terminated early due to low accrual.114 Another study in which patients were selected based on KRASG12D mutation status also showed one exceptional responder with 66% tumor regression.115 The authors later evaluated the p53 status of these patients based on preclinical in vivo studies showing increased response to proteasome inhibitors in a p53 null background compared to wild-type. Results were available in only 9 out of 22 patients due to tissue availability, and as a further caveat, p53 status was assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC), which is at best, an imperfect correlate for p53 mutational status with a significant rate of both false positivity and negativity.118 Of these, tumors from 3 of the patients were p53 mutant, while the other 6 retained wild type p53 as based on IHC staining. Two of three patients with presumed mutant p53 had stable disease with greater than 20% tumor shrinkage at 6 months, whereas one had progressive disease. Of the patients with IHC staining consistent with wild type p53 status, one was the exceptional responder while four had progressive disease.

In the only reported study evaluating the use of carfilzomib among several advanced solid cancer types, one patient with SCLC who had failed 6 prior chemotherapy regimens had a durable partial response with carfilzomib alone, and was continued on treatment for 39 cycles.116 Two more patients had stable disease. The study did not progress to stage 2, as the futility criteria were not met for any of the solid tumor types.

Overall, the results of these clinical trials of proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer are variable, and in many cases underwhelming, in contrast to what was expected from preclinical data. Nevertheless, there still remains evidence of activity of proteasome inhibitors. A few lessons are noteworthy and should be taken into consideration for future trials: 1) Combination treatment showed overall better response than single agent therapy across studies; 2) Concurrent combination of proteasome inhibitors with chemotherapeutics was more favorable than sequential therapy; 3) More cycles of bortezomib resulted in a longer progression-free course, for example, patients who received 8, 6 and 4 cycles demonstrated 11.5, 4.2 and 3.4 months of stable disease respectively.111 Another important consideration is that the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of different proteasome inhibitors to attain indicated levels within the tumor tissue were generally not evaluated in these studies.

The disappointing results from clinical trials employing proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer underscore the heterogeneity of lung cancer and suggest that a more rational approach to patient selection, choosing mechanistically appropriate proteasome inhibitors in target patient populations, and appropriate combination with other chemotherapeutics based on mechanisms of action, is warranted.

Conclusion and future directions

The evidence implicating mutant p53 in proteasomal hyperactivity, the known evasion of mutant p53 from degradation by the proteasome, and paradoxical degradation of mutant p53 upon prolonged proteasome inhibition, provides an attractive insight to the possibility that GOF p53 missense mutants can be targeted by manipulating the proteasome. However, to date, no clinical studies in lung cancer, or any other cancer, have prospectively selected patients based on p53 mutation status, and only very limited retrospective analyses have been performed to examine the efficacy of proteasome inhibitors in the subgroup of patients with mutant p53 alleles treated on prior proteasome inhibitor clinical trials. It is also important to note that the evidence for mutant p53 degradation upon proteasome inhibition has only been demonstrated in cell culture models, and preclinical in vivo studies of efficacy are currently lacking and will be needed to justify future trials. Moreover, results of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of currently studied proteasome inhibitors should be taken into consideration when designing future preclinical and clinical studies.

Published work thus far from pre-clinical (cell culture) experiments and clinical trials utilizing proteasome inhibitors in lung cancer and other solid tumors clearly supports investigation that furthers our understanding of the mechanistic pathway of mutant p53 degradation by proteasome inhibitors, which we believe will lead to novel therapeutic strategies to subvert mutant p53 gain-of-function oncogenic activities. Though this review has focused on lung cancer, such strategies will have a strong potential for generalizability across all tumor types characterized by high frequencies of missense gain of function p53 mutant alleles.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Grossman, S. Deb, and S.P. Deb labs for helpful comments and suggestions. SRG was supported by NCI R01CA172660.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R01CA172660].

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Cancer. [accessed 2019. July 13]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. 2019. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, RA O, BW B, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non–small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasim F, BF S, GA E. 2019. Lung cancer. Med Clin North Am. 103:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anagnostou VK, Brahmer JR. 2015. Cancer immunotherapy: A future paradigm shift in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 21:976–984. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peifer M, Fernández-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH, Plenker D, Leenders F, Sun R, Zander T, et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shetzer Y, Molchadsky A, Rotter V. Oncogenic mutant p53 gain of function nourishes the vicious cycle of tumor development and cancer stem-cell formation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6;a026203. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oren M, Rotter V. 2010. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2:a001107. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, Yin B, Willis NA, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Jacks T. 2004. Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cell. 2004:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrova EM, Yallowitz AR, Li D, Xu S, Schulz R, Proia DA, Lozano G, Dobbelstein M, Moll UM. 2015. Improving survival by exploiting tumour dependence on stabilized mutant p53 for treatment. Nature. 523:352–356. doi: 10.1038/nature14430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexandrova EM, Mirza SA, Xu S, Schulz-Heddergott R, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. P53 loss-of-heterozygosity is a necessary prerequisite for mutant p53 stabilization and gain-of-function in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health . ClinicalTrials.gov. [accessed 2019 October28]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=apr+246&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search.

- 13.National Institutes of Health . ClinicalTrials.gov. [accessed 2019 October28]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=hsp90+inhibitor&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=.

- 14.Halasi M, Pandit B, Gartel AL. 2014. Proteasome inhibitors suppress the protein expression of mutant p53. Cell Cycle. 13:3202–3206. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.950132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An WG, Chuman Y, Fojo T, Blagosklonny MV. 1998. Inhibitors of transcription, proteasome inhibitors, and DNA-damaging drugs differentially affect feedback of p53 degradation. Exp Cell Res. 244:54–60. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choudhury S, Kolukula VK, Preet A, Albanese C, Avantaggiati ML. 2013. Dissecting the pathways that destabilize mutant p53: the proteasome or autophagy? Cell Cycle. 12:1022–1029. doi: 10.4161/cc.24128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walerych D, Lisek K, Sommaggio R, Piazza S, Ciani Y, Dalla E, Rajkowska K, Gaweda-Walerych K, Ingallina E, Tonelli C, et al. Proteasome machinery is instrumental in a common gain-of-function program of the p53 missense mutants in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:897–909. doi: 10.1038/ncb3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali A, Wang Z, Fu J, Ji L, Liu J, Li L, Wang H, Chen J, Caulin C, Myers JN, et al. Differential regulation of the REGγ-proteasome pathway by p53/TGF-β signalling and mutant p53 in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2667. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vousden KH, Lu X. 2002. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. 2000. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu H, Levine AJ. 1995. Human TAFII31 protein is a transcriptional coactivator of the p53 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92:5154–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker KK, Levine AJ. 2002. Identification of a novel p53 functional domain that is necessary for efficient growth suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 93:15335–15340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joerger AC, Fersht AR. The tumor suppressor p53: from structures to drug discovery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chène P. 2001. The role of tetramerization in p53 function. Oncogene. 20:2611–2617. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg RL, Freund SMV, Veprintsev DB, Bycroft M, Fersht AR. Regulation of DNA binding of p53 by its C-terminal domain. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:801–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliner JD, Pietenpol JA, Thiagalingam S, Gyuris J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674:90644-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossman SR, Deato ME, Brignone C. Polyubiquitination of p53 by a ubiquitin ligase activity of p300. Science. 2003;300:342–344. doi: 10.1126/science.1080386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grossman SR, Perez M, Kung AL, Joseph M, Mansur C, Xiao Z-X, Kumar S, Howley PM, Livingston DM. 1998. p300/MDM2 complexes participate in MDM2-mediated p53 degradation. Mol Cell. 2:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig AL, Burch L, Vojtesek B, Mikutowska J, Thompson A, Hupp TR. 2015. Novel phosphorylation sites of human tumour suppressor protein p53 at Ser 20 and Thr 18 that disrupt the binding of mdm2 (mouse double minute 2) protein are modified in human cancers. Biochem J. 342:133–141. doi: 10.1042/bj3420133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appella E, Anderson CW. 2001. Post-translational modifications and activation of p53 by genotoxic stresses. Eur J Biochem. 268:2764–2772. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.0222x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ou YH, Chung PH, Sun TP, SS Y. 2005. p53 C-terminal phosphorylation by CHK1 and CHK2 participates in the regulation of DNA-damage-induced C-Terminal acetylation. Mol Biol Cell. 16:1684–1695. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-08-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yogosawa S, Yoshida K. 2018. Tumor suppressive role for kinases phosphorylating p53 in DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 109:3376–3382. doi: 10.1111/cas.13792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chehab NH, Malikzay A, Stavridi ES, Halazonetis TD. 1999. Phosphorylation of Ser-20 mediates stabilization of human p53 in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 96:13777–13782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shieh SY, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. 1997. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 91:325–334. doi: 10.1016/S00928674(00)80416-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert PF, Kashanchi F, Radonovich MF, Shiekhattar R, Brady JN. 1998. Phosphorylation of p53 serine 15 increases interaction with CBP. J Biol Chem. 273:33048–33053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito A, Lai CH, Zhao X, Saito S, Hamilton MH, Appella E, Yao T-P. 2001. p300/CBP-mediated p53 acetylation is commonly induced by p53-activating agents and inhibited by MDM2. Embo J. 20:1331–1340. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laptenko O, Prives C. 2006. Transcriptional regulation by p53: one protein, many possibilities. Cell Death Differ. 13:951–996. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris SL, Levine AJ. 2005. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene. 23:2899–2908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wasylishen AR, Lozano G. Attenuating the p53 pathway in human cancers: many means to the same end. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukashchuk N, Vousden KH. 2007. Ubiquitination and degradation of Mutant p53. Mol Cell Biol. 27:8284–8295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.00050-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li D, Marchenko ND, Schulz R, Fischer V, Velasco-Hernandez T, Talos F, Moll UM. 2011. Functional inactivation of endogenous MDM2 and CHIP by HSP90 causes aberrant stabilization of mutant p53 in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 9:577–588. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-10-0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu B, Gilkes DM, Farooqi B, Sebti SM, Chen J. 2006. MDMX overexpression prevents p53 activation by the MDM2 inhibitor nutlin. J Biol Chem. 281:33030–33035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shvarts A, Bazuine M, Dekker P, Ramos YFM, Steegenga WT, Merckx G, RCA VH, van der Houven van Oordt W, van der Eb AJ, AG J, et al. Isolation and identification of the human homolog of a new p53-binding protein, Mdmx. Genomics. 1997;43:34–42. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman Y, Pilpel Y, MicroRNAs OM. 2014. Alu elements in the p53-Mdm2-Mdm4 regulatory network. J Mol Cell Biol. 6:192–197. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SY, Lee JH, Ha M, Nam JW, Kim VN. 2009. miR-29 miRNAs activate p53 by targeting p85α and CDC42. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 16:23–29. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bou Kheir T, Futoma-Kazmierczak E, Jacobsen A. miR-449 inhibits cell proliferation and is down-regulated in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2011;10. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suh -S-S, Yoo JY, Nuovo GJ, Jeon Y-J, Kim S, Lee TJ, Kim T, Bakacs A, RH A, Kaur B, et al. MicroRNAs/TP53 feedback circuitry in glioblastoma multiforme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:5316–5321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202465109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olivier M, Goldgar DE, Sodha N, Ohgaki H, Kleihues P, Hainaut P, Eeles RA. Li-Fraumeni and related syndromes: correlation between tumor type, family structure, and TP53 genotype. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6643–6650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Mulvihill JJ, Blattner WA, Dreyfus MG, Tucker MA, Miller RW. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5358–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Curtis C. Human Cancers. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. 2010. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 1:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olivier M, Eeles R, Hollstein M, Khan MA, Harris CC, Hainaut P. 2002. The IARC TP53 database: new online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum Mutat. 19:607–614. doi: 10.1002/humu.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steels E, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, Branle F, Lemaitre F, Mascaux C, Meert AP, Vallot F, Lafitte JJ, Sculier JP. 2001. Role of p53 as a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 18:705–719. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitsudomi T, Hamajima N, Ogawa M, Takahashi T. Prognostic significance of p53 alterations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clinical Cancer Res. 2000;6:4055–4063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu J, Zhou Y, Huang L, Ou W, Wu J, Li S, Liu B. TP53 mutation is associated with a poor clinical outcome for non-small cell lung cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2016;5:705–713. doi:doi. 10.3892/mco.2016.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kandioler D, Stamatis G, Eberhardt W, Kappel S, Zöchbauer-Müller S, Kührer I, Mittlböck M, Zwrtek R, Aigner C, Bichler C. 2008. Growing clinical evidence for the interaction of the p53 genotype and response to induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 135:1036–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campling BG, El-Deiry WS. 2003. Clinical implication of p53 mutation in lung cancer. Mol Biotechnol. 24:141–156. doi: 10.1385/MB:24:2:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciechanover A. 2005. Proteolysis: from the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 6:79–86. doi: 10.1038/nrm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Recognition FD. 2009. Processing of Ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pickart CM, Cohen RE. 2004. Proteasomes and their kin: proteases in the machine age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 5:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vaughan CA, Pearsall I, Singh S, Windle B, Deb SP, Grossman SR, Yeudall WA, Deb S. 2016. Addiction of lung cancer cells to GOF p53 is promoted by up-regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor through multiple contacts with p53 transactivation domain and promoter. Oncotarget. 7:12426–12446. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kubbutat MHG, Jones SN, Vousden KH. 1997. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kubbutat MHG, Ludwig RL, Ashcroft M, Vousden KH. 2015. Regulation of Mdm2-directed degradation by the C terminus of p53. Mol Cell Biol. 18:5690–5698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joerger AC, Fersht AR. 2007. Structure-function-rescue: the diverse nature of common p53 cancer mutants. Oncogene. 26:2226–2242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Midgley CA, Lane DP. 1997. P53 protein stability in tumour cells is not determined by mutation but is dependent on Mdm2 binding. Oncogene. 15:1179–1189. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buschmann T, Minamoto T, Wagle N, Fuchs SY, Adler V, Mai M, Ronai Z. 2000. Analysis of JNK, Mdm2 and p14(ARF) contribution to the regulation of mutant p53 stability. J Mol Biol. 295:1009–1021. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimizu H, Saliba D, Wallace M, Finlan L, PRR L-S, Hupp TR. 2006. Destabilizing missense mutations in the tumour suppressor protein p53 enhance its ubiquitination in vitro and in vivo. Biochem J. 397:355–367. doi: 10.1042/bj20051521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prives C, White E. 2008. Does control of mutant p53 by Mdm2 complicate cancer therapy? Genes Dev. 22:1259–1264. doi: 10.1101/gad.1680508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Tan TH, Eliyahu D, Oren M, Levine AJ. Activating mutations for transformation by p53 produce a gene product that forms an hsc70-p53 complex with an altered half-life. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8(531–539):PMC363177. doi: 10.1128/MCB.8.2.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitesell L, Sutphin PD, Pulcini EJ, Martinez JD, Cook PH. 2015. The physical association of multiple molecular chaperone proteins with mutant p53 is altered by geldanamycin, an hsp90-binding agent. Mol Cell Biol. 18:1517–1524. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peng Y, Chen L, Li C, Lu W, Chen J. 2001. Inhibition of MDM2 by hsp90 contributes to mutant p53 stabilization. J Biol Chem. 276:40583–40590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schulz-Heddergott R, Moll UM. 2018. Gain-of-function (GOF) mutant p53 as actionable therapeutic target. Cancers (Basel). 10:1–16. doi: 10.3390/cancers10060188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Muller P, Hrstka R, Coomber D, Lane DP, Vojtesek B. 2008. Chaperone-dependent stabilization and degradation of p53 mutants. Oncogene. 27:3371–3383. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Esser C, Scheffner M, Höhfeld J. 2005. The chaperone-associated ubiquitin ligase CHIP is able to target p53 for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 280:27443–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Frum RA, Love IM, Damle PK, Mukhopadhyay ND, Palit Deb S, Deb S, Grossman SR. 2016. Constitutive activation of DNA damage checkpoint signaling contributes to mutant p53 accumulation via modulation of p53 ubiquitination. Mol Cancer Res. 14:423–436. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-15-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lisek K, Walerych D, Del Sal G. 2017. Mutant p53–Nrf2 axis regulates the proteasome machinery in cancer. Mol Cell Oncol. 4:e1217967. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2016.1217967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mortenson MM, Schlieman MG, Virudachalam S, Bold RJ. 2004. Effects of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib alone and in combination with chemotherapy in the A549 non-small-cell lung cancer cell line. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 54:343–353. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang Y, Ikezoe T, Saito T, Kobayashi M, Koeffler HP, Taguchi H. 2004. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 induces growth arrest and apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells via the JNK/c-Jun/AP-1 signaling. Cancer Sci. 95:176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xue Y, Barker N, Hoon S, He P, Thakur T, Abdeen SR, Maruthappan P, Ghadessy FJ, Lane DP, Stabilizes B. 2019. Activates p53 in proliferative compartments of both normal and tumor tissues in vivo. Cancer Res. 79:3595–3607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Schlossman R, Richardson P, Anderson KC. 2001. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in the pathophysiology of human multiple myeloma: therapeutic applications. Oncogene. 20:4519–4527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chauhan D, Uchiyama H, Akbarali Y, Urashima M, Yamamoto KI, Libermann TA, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma cell adhesion-induced interleukin-6 expression in bone marrow stromal cells involves activation of NF-kappa B. Blood. 1996;87:1104–1112. doi: 10.1182/blood.V87.3.1104.bloodjournal8731104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Mitsiades C, Mitsiades N, Hayashi T, Munshi N, Dang L, Castro A. 2002. Palombella V NF-kappa B as a therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem. 277:16639–16647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roy P, Sarkar UA, Basak S. 2018. The NF-κB activating pathways in multiple myeloma. Biomedicines. 6:59. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6020059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Demchenko YN, Kuehl WM. A critical role for the NFkB pathway in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2010;1(1):59–68. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Denlinger CE, Rundall BK, Keller MD, Jones DR. Proteasome inhibition sensitizes non-small-cell lung cancer to gemcitabine-induced apoptosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;781207–781214. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ling Y, Liebes L. Mechanisms of proteasome inhibitor PS-341-induced G 2 -M-Phase arrest and apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1145–1154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schenkein DP. Preclinical data with bortezomib in lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7(Suppl 2):S49–55. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2005.s.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Teicher BA, Ara G, Herbst R, Palombella VJ, Adams J. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in cancer theraapy. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2638–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sunwoo JB, Chen Z, Dong G, Yeh N, Crowl Bancroft C, Sausville E, Adams J, Elliott P, Van Waes C. Novel proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits activation of nuclear factor- B, cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1419–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boccadoro M, Morgan G, Cavenagh J. Preclinical evaluation of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2005;5:18. Published 2005 June1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adams J, Palombella VJ, Sausville EA, Johnson J, Destree A, Lazarus DD, Maas J, Pien CS, Prakash S, Elliott PJ, et al. Proteasome inhibitors: a novel class of potent and effective antitumor agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2615–2622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Frankel A, Man S, Elliott P, Adams J, Kerbel RS. Lack of multicellular drug resistance observed in human ovarian and prostate carcinoma treated with the proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3719–3728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mack PC, Davies AM, Lara PN, Gumerlock PH, Gandara DR. Integration of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341(Velcade) into the therapeutic approach to. Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;41(suppl1):S89–S9. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(03)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Davies AM, Ho C, Metzger AS, Beckett LA, Christensen S, Tanaka M, Lara PN, Lau DH, Gandara DR. 2007. Phase I study of two different schedules of bortezomib and pemetrexed in advanced solid tumors with emphasis on non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2:1112–1116. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815ba7d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dudek AZ, Lesniewski-Kmak K, Shehadeh NJ, Pandey ON, Franklin M, Kratzke RA, Greeno EW, Kumar P. 2009. Phase I study of bortezomib and cetuximab in patients with solid tumours expressing epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Cancer. 100:1379–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bommakanti SV, Dudek AZ, Khatri A, Kirstein MN, Gada PD. 2011. Phase 1 trial of gemcitabine with bortezomib in elderly patients with advanced solid tumors. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials. 34:597–602. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181f9441f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Voortman J, Smit EF, Honeywell R, Kuenen BC, Peters GJ, van de Velde H, Giaccone G. 2007. A parallel dose-escalation study of weekly and twice-weekly bortezomib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 13:3642–3651. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jones DR, Moskaluk CA, Gillenwater HH, Petroni GR, Burks SG, Philips J, Rehm PK, Olazagasti J, Kozower BD, Bao Y. 2012. Phase I trial of induction histone deacetylase and proteasome inhibition followed by surgery in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 7:1683–1690. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318267928d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Millward M, Price T, Townsend A, Sweeney C, Spenser A, Sukumaran S, Longenecker A, Lee L, Lay A, Sharma G, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor marizomib with the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat in patients with melanoma, pancreatic and lung cancer based on in vitro assessments of the combination. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:2303–2317. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9766-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fanucchi MP, Fossella FV, Belt R, Natale R, Fidias P, Carbone DP, Govindan R, Raez LE, Robert F, Ribiero M. 2006. Randomized phase II study of bortezomib alone and bortezomib in combination with docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 24:5025–5033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lynch TJ, Fenton D, Hirsh V, Bodkin D, Middleman EL, Chiappori A, Halmos B, Favis R, Liu H, WL T, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of erlotinib alone and in combination with bortezomib in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1002–1009. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181aba89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lilenbaum R, Wang X, Gu L, Kirshner J, Lerro K, Vokes E. 2009. Randomized phase II trial of docetaxel plus cetuximab or docetaxel plus bortezomib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2: CALGB 30402. J Clin Oncol. 27:4487–4491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Scagliotti GV, Germonpré P, Bosquée L, Vansteenkiste J, Gervais R, Planchard D, Reck M, De Marinis F, Lee JS, Park K. 2010. A randomized phase II study of bortezomib and pemetrexed, in combination or alone, in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 68:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lara PN, Longmate J, Reckamp K, Gitlitz B, Argiris A, Ramalingam S, Belani CP, Mack PC, Lau DHM, Koczywas M, et al. Randomized phase II trial of concurrent versus sequential bortezomib plus docetaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A california cancer consortium trial. Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12:33–37. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2011.n.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoang T, Campbell TC, Zhang C, Kim K, Kolesar JM, KR O, JH B, Robinson EG, Ahuja HG, Kirschling RJ, et al. Vorinostat and bortezomib as third-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A wisconsin oncology network phase II study. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:195–199. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9980-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao Y, Foster NR, Meyers JP, Thomas SP, Northfelt DW, Rowland KM, Mattar BI, Johnson DB, Molina JR, Mandrekar SJ, et al. A phase I/II study of bortezomib in combination with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and concurrent thoracic radiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG)-N0321. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:172–180. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kontopodis E, Kotsakis A, Kentepozidis N, Syrigos K, Ziras N, Moutsos M, Filippa G, Mala A, Vamvakas L, Mavroudis D, et al. A phase II, open-label trial of bortezomib (VELCADE®) in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:949–956. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-2997-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Davies AM, Chansky K, Lara PN, Gumerlock PH, Crowley J, Albain KS, Vogel SJ, Gandara DR. 2009. Bortezomib plus gemcitabine/carboplatin as first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A phase II southwest oncology group study (S0339). J Thorac Oncol. 4:87–92. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181915052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Piperdi B, Walsh WV, Bradley K, Zhou Z, Bathini V, Hanrahan-Boshes M, Hutchinson L, Perez-Soler R. 2012. Phase-I/II study of bortezomib in combination with carboplatin and bevacizumab as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 7:1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824de2fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li T, Ho L, Piperdi B, Elrafei T, Camacho FJ, Rigas JR, Perez-Soler R, Gucalp R. 2010. Phase II study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341, Velcade®) in chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Lung Cancer. 68:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Besse B, Planchard D, Veillard A-S, Taillade L, Khayat D, Ducourtieux M, Pignon J-P, Lumbroso J, Lafontaine C, Mathiot C, et al. Phase 2 study of frontline bortezomib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lara PN, Chansky K, Davies AM, Franklin WA, Gumerlock PH, Guaglianone PP, Atkins JN, Farneth N, Mack PC, Crowley JJ, et al. Bortezomib (PS-341) in relapsed or refractory extensive stage small cell lung cancer: A Southwest oncology group phase II trial (S0327). J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:996–1001. doi: 10.1097/01243894-200611000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ramalingam SS, Davies AM, Longmate J, Edelman MJ, Lara PN, Vokes EE, Villalona-Calero M, Gitlitz B, Reckamp K, Salgia R, et al. Bortezomib for patients with advanced-stage bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: A California cancer consortium phase II study (NCI 7003). J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1741–1745. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318225924c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Drilon A, Schoenfeld AJ, Arbour KC. Exceptional responders with invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas: a phase 2 trial of bortezomib in patients with KRAS G12D-mutant lung cancers. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Papadopoulos KP, Burris HA, Gordon M, Lee P, Sausville EA, Rosen PJ, Patnaik A, Cutler RE, Wang Z, Lee S, et al. A phase I/II study of carfilzomib 2-10-min infusion in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;72:861–868. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2267-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.National Institutes of Health . Clinical Trials.Gov. [accessed 2019 June12]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Lung+Cancer&term=Carfilzomib&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=.

- 118.Taylor D, Koch WM, Zahurak M, Shah K, Sidransky D, Westra WH. Immunohistochemical detection of p53 protein accumulation in head and neck cancer: correlation with p53 gene alterations. Hum Pathol. 1999. October;30:1221–1225. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization . Cancer. [accessed 2019. July 13]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.