Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is a rare soft tissue tumor which can be detected in many parts of the body. Its etiology and clinical behavior are not fully understood, and its treatment is controversial. This study aimed to present the management of a pancreatic tail case presenting with extracolonic obstruction findings. Unblock distal pancreatectomy + left surrenalectomy + left hemicolectomy + splenectomy operation was made with R0 resection principles. Although there are some medical treatments reported in children and unresectable tumors in the medical literature, complete surgical resection following oncological principles seems to be the most important and main treatment modality in the treatment of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. However, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor has many aspects that are not yet clearly understood, and it is a disease being continuously researched.

Keywords: Myofibroblastic, pancreas, mass

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare soft tissue tumor which can be detected in many parts of the body. Its etiology and clinical behavior are not fully understood, and its treatment is controversial (1-5). Although this unusual disease has a relatively good prognosis, its differential diagnosis from other malignant diseases is challenging. In our study, we presented the management of a pancreatic tail case presenting with extracolonic obstruction findings. The aim of this study was to discuss our patient that had IMT originating from the tail of pancreas in light of the literature.

Case Report

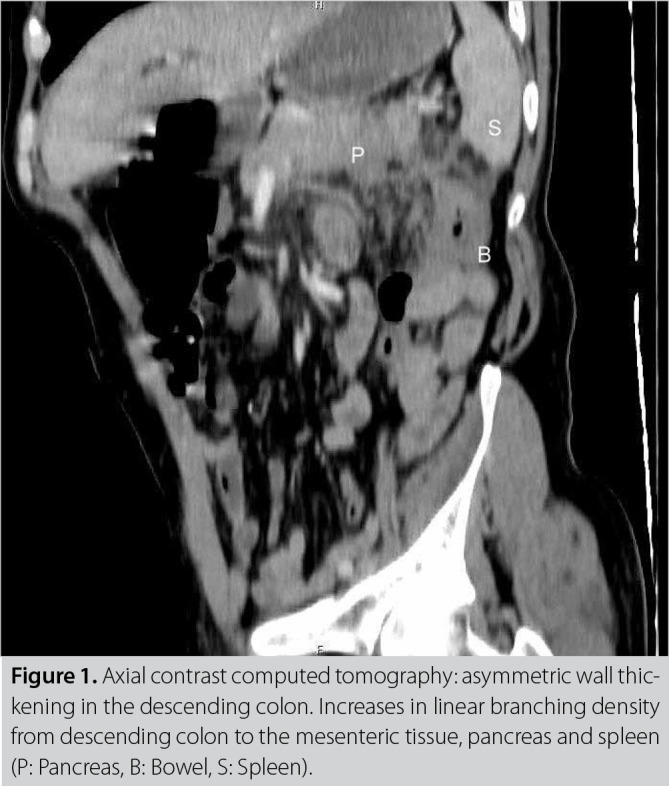

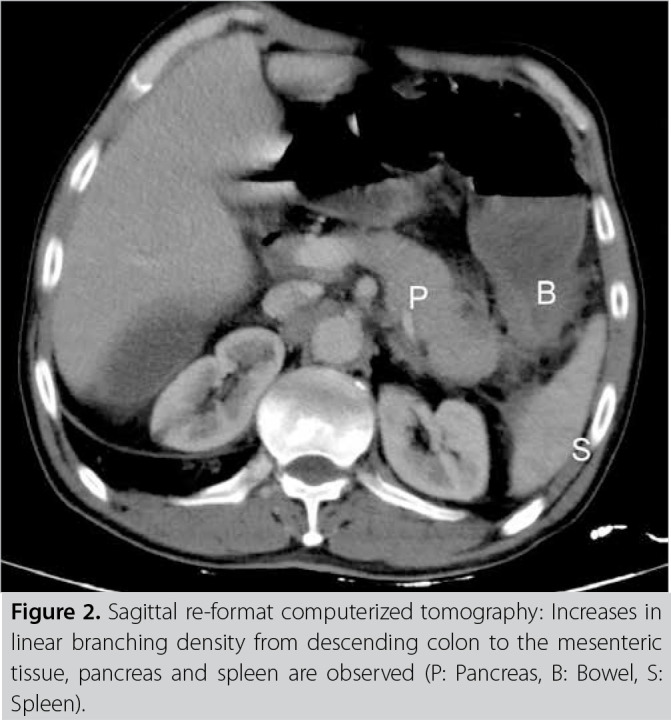

A 61-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain. Blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg and Heart rate: 90/min. There was no personal or family history. There was mild distension and moderate sensitivity in abdominal examination. No special condition was detected in other whole-body system examinations. Antral gastritis was found in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. In colonoscopy, there was an impression of external compression in the descending colon which did not allow proximal transition. Wbc: 9200 103/10 µL, hemoglobin: 10.8 mg/dL, and tumor markers (CEA, CA-19-9) were within normal limits. Whole abdominal tomography revealed diffuse wall thickening in the descending colon and marked dilatation of the proximal colon segments. Marked inflammatory changes were observed in fatty tissue in the pericolic area (Figures 1, 2). It was decided to perform laparotomy on the patient for diagnosis and treatment. Exploration revealed a mass of approximately 10 cm, which was thought to be of distal pancreas origin, with 2 cm invasion of the anterior abdomen wall, covering the colonic splenic flexure, left surrenal and splenic vessels, and which was attached to the jejunum adjacent to the treitz ligament, the left kidney parenchyma and mezo via desmoplastic reaction. Considering oncological principles, the desmoplastic adhesions of the tumor with the left kidney and the jejunum in the treitz ligament were separated and the anterior abdominal wall muscle fibers were included into the piece according to R0 resection, and the patient underwent unblock distal pancreatectomy + left surrenalectomy + left hemicolectomy + splenectomy operation (Figure 3). Postoperatively, the patient developed a low flow pancreatic fistula with a daily flow rate of 400 cc. Following oddi sphincterotomy via endoscopic retrograde cholanjio-pancreatography (ERCP), the fistula was closed with medical treatment and follow-up. The patient was discharged on the 16th postoperative day. Resection material was fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution (%10 NB Formaldehyde, Novogen Diagnostik, Istanbul, Turkey) and delivered to the pathology laboratory. On gross examination, macroscopy revealed a colon without any pili due to severe edema of 26 cm on a 15 x 13 x 7 cm irregularly shaped material. A 10 cm mass lesion that encapsulated the colon from the middle section had narrowed the lumen due to compression. The mass had 2 cm surrenal muscle area on one side and 2 cm irregular muscle area on the other side.

Figure 1. Axial contrast computed tomography: asymmetric wall thic- kening in the descending colon. Increases in linear branching density from descending colon to the mesenteric tissue, pancreas and spleen (P: Pancreas, B: Bowel, S: Spleen).

Figure 2. Sagittal re-format computerized tomography: Increases in linear branching density from descending colon to the mesenteric tissue, pancreas and spleen are observed (P: Pancreas, B: Bowel, S: Spleen).

Figure 3. En bloc resection including the colon, mesenteric fatty tis- sue, partial pancreas and adrenal gland.

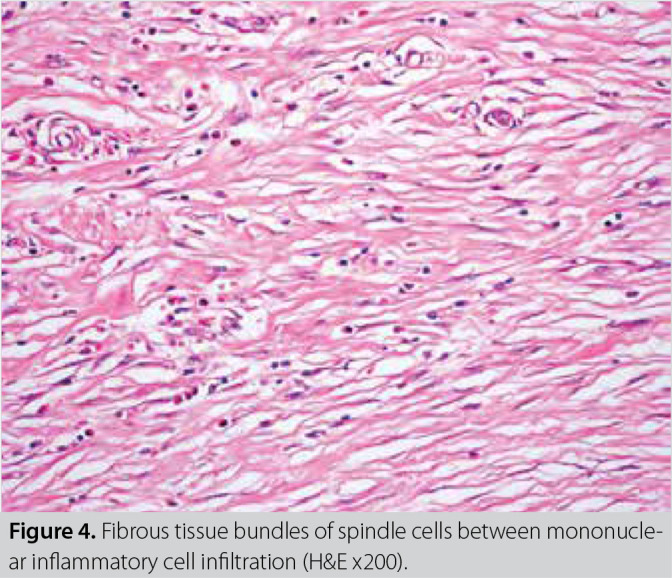

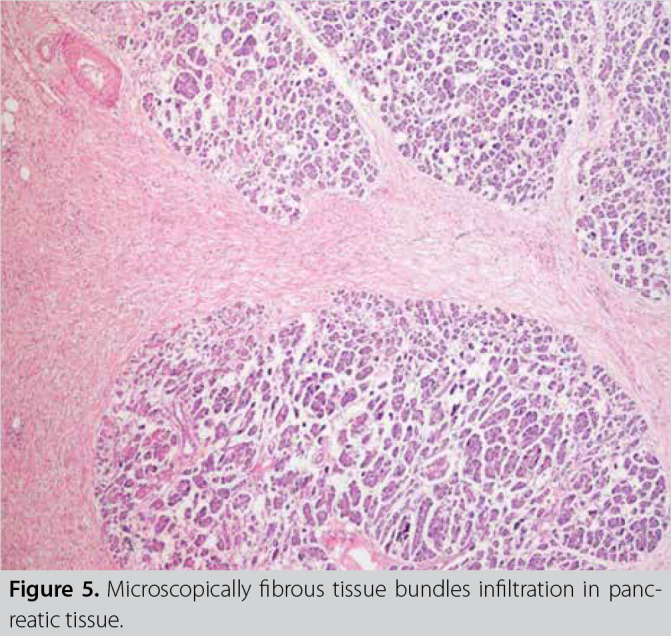

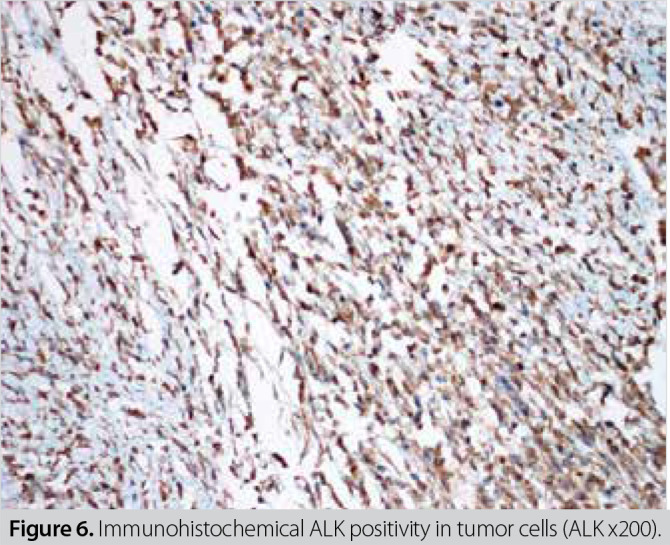

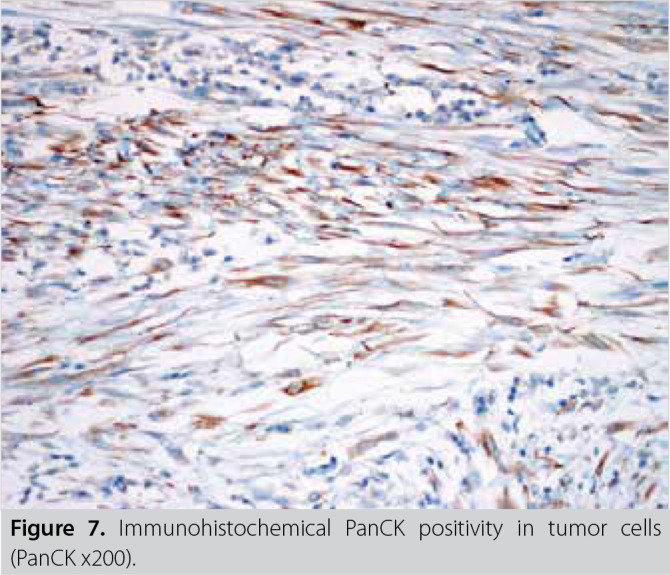

On histopathologic examination, a tumoral lesion was observed predominantly consisting of cytologically bland spindle- or stellate-shaped cells loosely arranged in an edematous or hyaline stroma with scattered plasma cells and lymphocytes. Tumoral cells were arranged in a storiform or fascicular growth pattern with a limited infiltrative border neighboring organs. Inflammatory cells were formed in small clusters in some areas. No cytologic atypia, atypical mitotic figures or necrosis were seen. Immunohistochemical study revealed in a strong intensity, diffuse positive staining for vimentin and alpha smooth muscle actin; in a weak-moderate intensity, focal positive staining for pancytokeratin and in a weak-moderate, near diffuse positive staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Positive staining for IgG4 antibody was seen in a few scattered plasma cells. The tumor cells did not stain with IgG4. Likewise, the tumoral cells did not stain with DOG-1, CD117, beta-catenin, desmin and S-100 protein. On the basis of morphologic and immunohistochemical staining results, the case was diagnosed as IMT (Figure 4-7).

Figure 4. Fibrous tissue bundles of spindle cells between mononucle- ar inflammatory cell infiltration (H&E x200).

Figure 5. Microscopically fibrous tissue bundles infiltration in panc- reatic tissue.

Figure 6. Immunohistochemical ALK positivity in tumor cells (ALK x200).

Figure 7. Immunohistochemical PanCK positivity in tumor cells (PanCK x200).

No problems were detected in the polyclinic follow-up of the patient and informed consent was obtained for publication. No evidence of relapse or metastasis was observed in the laboratory and radiological tests performed at the 8th month.

Discussion

IMT is a rare disease. It is known in the literature as inflammatory fibrosarcoma, inflammatory pseudotumor or IMT. Its prevalence in men and women is generally equal, and it is seen in a very wide age range of 0-82 (1-3).

IMT can be seen in many parts of the body. Locations where it can be seen cover a very broad spectrum; including the pancreas, lungs, tongue, heart mediastinum, extremities, liver, small intestine, brain, placenta, pelvis, retroperitoneum, epiglottis, kidney, bladder and testis (3-5). When this disease is located in the pancreas, it can be seen in the tip, body or the tail of the pancreas (1). In our case, it was located in the pancreatic tail.

Clinical symptoms of the disease are associated with its location. It can be detected by radiological tests or examination as a result of non-specific complaints, or it can also present itself with a mass or associated symptoms, findings or complications (1,6). In our case, the tumor did not cause mass formation radiologically, and presented itself through the complication of colonic obstruction. In addition, there are also atypical cases in the literature presenting with psychiatric disorders such as anorexia nervosa (7).

Although it has been reported in the literature to be generally locally aggressive and non-metastatic, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas may also show lymphatic metastasis (4). Peritoneal dissemination of stomach-induced IMT has also been shown in the literature (8).

As with many tumor types, radiological or laboratory diagnosis is not possible and histopathological diagnosis is required. This may be a biopsy accompanied by interventional radiology; however, diagnosis is usually made after surgical excision, as in our case.

In cases with pancreatic lesions, surgery is usually performed with laparotomy as in our case, but laparoscopic resection may also be a treatment option (2).

There are cases in the literature where remission is achieved with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitors when surgical resection is not possible and also cases showing a good response to methotrexate and vinorelbine chemotherapy (5,9). On the contrary, there are cases showing no response to adriamycin and gemcitabine chemotherapy (6).

Complete surgical resection following oncological principles is seen as the most important and main treatment method in the treatment of this disease (10,11). Postoperative adjuvant therapy is not recommended, but long-term follow-up is required. As a matter of fact, IMT has a local recurrence rate of 15-37% (10,12).

Histopathologic differential diagnosis of this case included fibromatosis (desmoid tumor), extraintestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumor, IgG4-related sclerosing diseases and less likely other tumors with spindle cells. The immunohistochemical reactivity of the spindle and stellate cells for pancytokeratin and ALK and negativity for beta-catenin, CD117, DOG-1 assist in distinguishing IMT from fibromatosis and extraintestinal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. IgG4-related sclerosing lesions are usually a group of disorders ill-defined, entrapping the normal tissues in the vicinity. They tend to have more intense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory cell infiltration and prominent sclerosis and phlebitis than the typical IMT. Recently, a number of studies have found IgG4-positive plasma cells in IMTs (13). Likewise, IgG4 positivity was detected in a small number of cells in our case.

For other tumors composed of elongated spindle cells arranged in a fascicular or storiform growth pattern, differentiation from IMTs may less likely pose a problem. These entities include fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. These tumors usually contain high cellularity, higher nuclear atypia, more mitotic figures and necrosis than IMTs. Indeed, the immune staining pattern is different these tumors and solves the problem.

Lacoste et al. (14) have reported that high-dose steroid treatment resulted in tumor regression and tumor disappeared in pancreatic inflammatory tumor in children and the disease was not detected during 2-year follow-up.

In conclusion, complete surgical resection following oncological principles seems to be the most important and main treatment modality in the treatment of IMTs. However, IMT has many aspects that are not yet clearly understood, and it is a disease being continuously researched.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Peer Review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patient who participated in this case.

Author Contributions: Concept - N.İ., S.K.K.; Design - N.İ., S.K.K., S.Ü.; Supervision - N.İ., S.K.K., S.Ü., S.D.; Materials - T.B., H.G., S.Ü.; Data Collection and/or Processing - N.İ., S.K.K., S.D.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - S.D., S.Ü., O.N.G., H.G.; Literature Search - N.İ., S.K.K., T.B., H.G.; Writing Manuscript - N.İ., S.K.K., H.G., O.N.G.; Critical Reviews - H.G., O.N.G.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Casadei R, Piccoli L, Valeri B, Santini D, Zanini N, Minni F, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the pancreas resembling pancreatic cancer: clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Chir Ital. 2004;56(6):849–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeRubertis BG, McGinty J, Rivera M, Miskovitz PF, Fahey TJ 3rd. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for inflammatory pseudotumor of the pancreas. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(6):1001–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-4546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caporalini C, Moscardi S, Tamburini A, Pierossi N, Di Maurizio M, Buccoliero AM. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the Tongue. Report of a pediatric case and review of the literature. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2018;37(2):117–125. doi: 10.1080/15513815.2017.1385667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanger P, Kronsbein U, Merkle P, Bosse A. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas with regional lymph node involvement. Pathologe. 2002;23(2):161–166. doi: 10.1007/s00292-002-0523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maruyama Y, Fukushima T, Gomi D, Kobayashi T, Sekiguchi N, Sakamoto A, et al. Relapsed and unresectable inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor responded to chemotherapy: a case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7(4):521–524. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poves I, Alonso S, Jimeno M, Bessa X, Burdío F, Grande L. Retroperitoneal inflammatory pseudotumor presenting as a pancreatic mass. JOP. 2012;13(3):308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding D, Bu X, Tian F. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the head of the pancreas with anorexia and vomiting in a 69-year-old man: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(2):1546–1550. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KA, Park CM, Lee JH, Cha SH, Park SW, Hong SJ, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the stomach with peritoneal dissemination in a young adult: imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29(1):9–11. doi: 10.1007/s00261-003-0085-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob SV, Reith JD, Kojima AY, Williams WD, Liu C, Vila Duckworth L. An unusual case of systemic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with successful treatment with ALK-inhibitor. Case Rep Pathol. 2014;2014:470340–470340. doi: 10.1155/2014/470340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Watanabe K, Nagata M, Tasaki K, Honda I, Watanabe S, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9(1):116–119. doi: 10.1007/s005340200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panda D, Mukhopadhyay D, Datta C, Chattopadhyay BK, Chatterjee U, Shinde R. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor arising in the pancreatic head: a rare case report. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(6):538–540. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1322-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(8):859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida K, Satoi S, Miyoshi H, Hachimine D, Ikeura T, Shimatani M, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the pancreas and liver with infiltration of IgG4-positive plasmacells. Intern Med. 2007;46(17):1409–1412. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacoste L, Galant C, Gigot JF, Lacoste B, Annet L. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreatic head. JBR-BTR. 2012;95(4):267–269. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]