Abstract

Backgrounds and aims

As COVID-19 spreads rapidly, this global pandemic has not only brought the risk of death but also spread unbearable psychological pressure to people around the world. The aim of this study was to explore (a) the mediating role of rumination in the association between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences of college students, and (b) the moderating role of psychological support in the indirect relationship between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences of college students.

Methods

Eight hundred and forty-one Chinese college students (Mage = 19.50 years, SD = 1.580) completed the measures of stressors of COVID-19, stress consequences, rumination, and psychological support.

Results

Stressors of COVID-19 were significantly positively associated with stress consequences, and mediation analyses indicated that rumination partially mediated this association. Moderated mediation analysis further revealed that psychological support buffered the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and rumination, as well as the relation between rumination and stress consequences.

Discussion and conclusion

Findings of this study demonstrated that stressors associated with COVID-19 is positively related to rumination, which in turn, is related to stress consequences in college students. However, psychological support buffered this effect at both indirect mediation paths, suggesting that college students with greater psychological support may be better equipped to prevent negative stress consequences.

Keywords: COVID-19 stressor, Rumination, Stress consequence, Psychological support

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease continues to spread rapidly at a global scale. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified the emergence of the novel coronavirus as a pandemic and a health emergency of global concern (PHEIC) (Eurosurveillance Editorial Team, 2020). On Feb 11, 2020, this novel coronavirus was officially named as Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) by WHO. As of August 25, 2020, more than 23 million confirmed cases with 800,000 deaths had been reported worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020a). While the global virus has sparked an unprecedented response among the scholarly community, the large majority of recent topics of inquiry have been concerning emergency care, viral pathogenesis, and so forth. In contrast, attention to the impact of COVID-19 on people’s mental health, particularly for the younger population, have been scant (Tran, Ha, et al., 2020).

COVID-19 not only endangers people's health and lives but is also likely to yield short and long-term negative psychological consequences for human societies. Several early studies on the psychological effects of COVID-19 showed notable prevalence of anxiety, depression, stress (Wang et al., 2020a), insomnia (Hao et al., 2020), and post-traumatic stress disorder (Tan et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020) among those affected. In particular, those who experienced physical symptoms of COVID-19 were also 2–3 times more likely to report having the aforementioned negative psychological symptoms (Chew, Lee, et al., 2020). The prolonged prevalence of COVID-19 remains a source of great psychological pressure, both for the general public (Wang et al., 2020a) and specific sectors of society (Chew et al., 2020, Hao et al., 2020, Tan et al., 2020).

With the salience of the increasing number of COVID-19 infections, widespread dissemination of misinformation (dubbed the COVID-19 infodemic; World Health Organization, 2020b), and unavailability of epidemic prevention resources in the marketplace, those residing in close proximity of epicenters of COVID-19 may be highly susceptible to the negative outcomes of acute and chronic stress (Liu et al., 2020). Indeed, stressors have long been documented to be strong risk factors of several mental health consequences, such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia (Pappa et al., 2020, Vedhara et al., 2000, Wahab et al., 2013). However, not everyone under these stressors will exhibit negative outcomes; those who are well-equipped to adequately cope with the stressors may be able to appropriate their psychological and cognitive resources to manage impending or concurrent issues (Lazarus, 1993).

Because one’s overall well-being is largely contingent on their mental health (Prince et al., 2007), it remains important to examine the psychological consequences of stressors stemming from COVID-19 related issues. Heretofore, we refer to these stress-induced consequences stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic as simply stress consequences. Given the novelty of COVID-19, however, it is unclear how the specific stressors associated with the disease may have impacted Chinese college students early in the pandemic. Thus, the aim of the present study is to investigate whether the stressors of COVID-19 experienced by college students is significantly associated with stress consequences and examine the potential mediating and moderating mechanisms in this association.

1.1. The mediating role of rumination

In examining the consequences of sudden stressors, it is important to consider the possible mediators that may play a role in increasing stress consequences. In particular, rumination may be a subsequent consequence of sudden stressors as well as being an antecedent of stress consequences. Rumination is a maladaptive form of cognitive self-reflection, characterized by repeated thoughts and recollection of feelings associated with negative events (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008, Robinson and Alloy, 2003). The perseverative cognition hypothesis posits that rumination is a common response to stress and reasons that such perseverative cognition exacerbates stress consequences as stressors are prolonged under a ruminative state (Brosschot, Gerin, & Thayer, 2006). Rumination is commonly regarded as a poor coping strategy, characterized by its passive nature and tendency to hinder individual social problem solving. Indeed, prior research has shown that individuals exhibiting high levels of rumination are often coupled with facing their problems more negatively and divorced from adaptive problem-solving behaviors that otherwise serve to address the source of the issue (Hasegawa et al., 2015). As rumination is associated with increased negative emotions and decreased suppression of negative information, this unique cognitive mechanism serves as a catalyst in the cycle of negative emotions and cognitions (Liu & Tian, 2013). This sustained negative patterns of emotion and cognition has been documented to result in a plethora of adverse health consequences, such as impaired sleep (Allen, 2007), sleep disorders (Butz and Stahlberg, 2018, Guastella and Moulds, 2007, Takano et al., 2012), depression and anxiety (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010), and decreased health levels (Joormann & Gotlib, 2010).

While past studies have evidenced that rumination predicts a diverse range of stress consequences, no studies to date have directly investigated the mediating role of rumination in the association between COVID-19 related stressors and stress consequences in college students. Many scholars have conceptualized rumination as a risk or protective factor (i.e., it buffers or exacerbates the effects of stress). However, the unique and unusual social ecology brought about by COVID-19 warrant examining rumination as a consequence of COVID-19 stressors. Rumination has been documented to be influenced by perceived stress (Chen and Huang, 2019, Wang et al., 2019) and because attention increases under high levels of vigilance (Qi & Gao, 2020), the cognitive behavior presents itself as a natural, but potentially dangerous, variable in models of stress consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008) for adolescents (Skitch & Abela, 2008). Specifically, rumination has been evidenced to be a mutable variable in response to stressful life events (e.g., Li et al., 2019, Liu and Wang, 2017, Michl et al., 2013) and can play a mediating role between changing stressors and their respective consequences, such as work stressors and impaired sleep (Berset, Elfering, Lüthy, Lüthi, & Semmer, 2011) and perceived stress and depression (Wang et al., 2019). As COVID-19 brought about sudden changes to our social ecology, as well as great uncertainty regarding the impending future, rumination tendencies may increase in those who may not have otherwise be susceptible in response to more routine stressors. Indeed, as COVID-19 presents a host of salient stressors pertaining to both the individual and others at an alarming degree, and with little to no certain solutions in sight, students may find themselves ruminating over possible outcomes that may befall on them or their close ones. Given the uncertainty associated with the course of COVID-19, it stands to reason that students may engage in more rumination as their stressors increase, which in turn may increase their risk for developing several negative psychological outcomes.

1.2. The moderating role of psychological support

COVID-19 stressors may increase college students’ stress consequences through the mediating role of rumination, but there is a diverse range of sensitivity among individuals with regard to how they respond to stressors. In other words, not all college students with high COVID-19 stressors may engage in a high level of rumination or experience the detriments of COVID-19 stressors or rumination. One key buffering mechanism may be psychological support. Psychological support is defined as the capacity to use internal and external resources to establish an environmental and individual support system in an effort to maintain and promote one’s mental health (Zhou & Zhang, 2017). Because stress consequences result from a dynamic interplay between risk and protective factors (Masten, 2001), psychological support may serve as a protective factor against psychological risk factors specific to COVID-19 (i.e., COVID-19 related stressors). In other words, psychological support may weaken the negative association between COVID-19 stressors and its subsequent stress consequences. Findings from several studies allude to supporting this notion. For instance, social support has been documented to yield favorable sleep outcomes (Kent de Grey, Uchino, Trettevik, Cronan, & Hogan, 2018), such as lower levels of insomnia severity (Kim & Suh, 2019). Further, social support has been evidenced to buffer the adverse impact of negative life events on wellbeing (Nezlek & Allen, 2006) as well as perfectionism on depression and anxiety (Zhou, Zhu, Zhang, & Cai, 2013). That is, social support plays a critical role in reducing depression (Bouteyre et al., 2007, Costa et al., 2017).

Psychological support may be particularly prevalent and effective during times of pandemics. The history of epidemics has generally observed the public utilizing more psychological coping strategies, such as problem-focused coping as well as seeking social support as negative stress consequences also rise (Chew, Wei, Vasoo, Chua, & Sim, 2020). During the SARS epidemic, individuals reported receiving more social support from family and friends compared to before the epidemic (Lau, Yang, Tsui, Pang, & Wing, 2006). While the efficacy of psychological support in combatting the stress consequences specific to COVID-19 requires more investigation, an early report yielded promising results showing that social support was negatively associated with the degree of anxiety and stress (Xiao, Zhang, Kong, Li, & Yang, 2020). However, further examination of this buffering effect is warranted given the ubiquity of COVID-19 related stressors in recent times and the accessibility of psychological stressors as a possible protective mechanism. To date, no previous studies examined whether psychological support as a protective factor that buffers the adverse impact of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences and a moderator in the indirect relation between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequence via rumination.

1.3. Present study

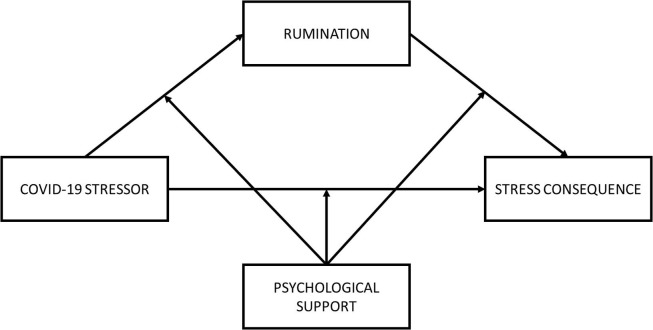

The purposes of this research were twofold: (a) to test whether rumination would mediate the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences in college students, and (b) to test whether the direct and indirect relations between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences via rumination were moderated by psychological support. The proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 1 . Based on the review of literature, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Rumination will mediate the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences.

Hypothesis 2

Psychological support will moderate the direct and indirect relations between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences via rumination.

Fig. 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 841 college students in China (Mage = 19.50, SD = 1.580, range = 18–25, 61.0% Female) participated in this study from February 17 to March 15, 2020. Participation in this study was entirely voluntary and no compensation was given to participants for their participation. To abide by local government policies, the study questionnaire was distributed to potential participants electronically via SurveyStar (Changsha Ranxing Science and Technology, Shanghai, China) and no face-to-face contact was made. All participants consented to participation and data were anonymized. Furthermore, 68.6% of these participants were 1st year standing, 16.5% were 2nd year standing, 10.0% were 3rd year standing, and 4.9% were 4th year standing. Fifty-three percent reported residency in urban settings. As the Ministry of Education in China extended Winter recess from February 2020 to April 2020, universities were not in active session when data were collected.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Stressors of COVID-19

We compiled the COVID-19 stressors scale, comprised of 19 items, α = 0.942 (see Supplemental Materials for the scale). The scale included four dimensions: (1) disease stressors of COVID-19 (7 items; e.g., “I am worried that I will be infected by COVID-19”), (2) information stressors of COVID-19 (4 items; e.g., “I heard some negative news about COVID-19”), (3) measures stressors of COVID-19 (4 items; e.g., “Academic schedule was disrupted”), and (4) environmental stressors of COVID-19 (4 items; e.g., “I am separated and alienated from my classmates and friends”). Participants rated each item on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (No Stress) to 5 (Great Stress). Greater mean scores indicated higher levels of COVID-19 related stress.

2.2.2. Rumination

The Chinese Version (Han & Yang, 2009) of the Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS) (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) was administered to measure participants’ level of rumination, α = 0.950. The scale consisted of 22 items (e.g., “I go away by myself and think about why I feel this way” and “I think back to other times I have been depressed”) and included three dimensions: (1) brooding (5 items), (2) reflective pondering (5 items), and (3) symptom rumination (12 items). Participants rated each item on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always), with higher mean scores indicating higher levels of rumination. This scale has been used in the Chinese population (e.g., Chen et al., 2018, Cui et al., 2017, Li et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2020b) and shown good reliability and validity.

2.2.3. Stress consequences

Stress consequences were assessed by the Pressure Effect Scale (Liu, 2014) which comprised 17 items (e.g., “Difficulty concentrating,” “Poor appetite, loss of appetite,” “Easy to lose temper and feel irritable”; see Supplemental Materials for scale). The scale included three dimensions: (1) behavioral symptoms (6 items), (2) psychological symptoms (7 items), (3) physical symptoms (4 items), with good reliability and validity in Chinese samples, α = 0.869. Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with higher scores showing higher levels of stress consequences.

2.2.4. Psychological support

Psychological support was measured by the College Students Psychological Support Scale (Zhou & Zhang, 2017), with good reliability and validity in Chinese samples, α = 0.851. The scale consisted of 26 items (e.g., “I can turn to the right person for help when I'm in trouble.”) and included five dimensions: (1) Self-acceptance (7 items) (e.g., “I'm indecisive when it comes to decision-making.”), (2) responsible talk (self-care; 6 items) (e.g., “I'm good at relieving myself.”), (3) coping strategy (5 items) (e.g., “I have many ways of dealing with problems.”), (4) spiritual pillar (4 items) (e.g., “I have role models to inspire me and help me through the tough times.”), and (5) intimate relationship (4 items) (e.g., “I can find resources from my surroundings to help me.”). Participants rated each item on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher mean scores indicating higher levels of psychological support.

2.3. Procedure

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the first author’s institution. We obtained consent from all participating college students before data collection. Participants were given the survey questionnaire where they provided demographic information and completed the measurements listed above.

2.4. Data analysis

The purpose of this study was to explore whether rumination played a mediating role between the stressors of COVID-19 and the stress consequences of college students, and whether psychological support played a moderating role in the indirect path between the stressors of COVID-19 and the direct path between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences. These research questions were tested in three steps. First, the descriptive statistics and bi-variate Pearson correlations were calculated. Second, the mediating effect of rumination was examined by using PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4) (Hayes, 2017). Third, the analyses of the moderating effect of psychological support on the direct and indirect links between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences were constructed applying the PROCESS macro (Model 59). All study continuous variables were standardized, and the models utilized 5000 resamples through bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs) to determine whether the effects in PROCESS Model 4 and Model 59 were significant (Hayes, 2017).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Table 1 lists the means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, bi-variate correlations, and Cronbach’s α for the study variables. The data were examined for normality of distribution by skewness and kurtosis (Kline, 2015). The skewness and kurtosis of all variables were within the acceptable ranges (|skewness| < 3 and |kurtosis| < 10). As expected, stressors of COVID-19 were positively correlated with rumination and stress consequences, but negatively correlated with psychological support. Rumination was positively and negatively correlated with stress consequences and psychological support, respectively. Additionally, stress consequence was negatively correlated with psychological support.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations.

| Variable | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SOC | 2.39 | 0.71 | 0.074 | −0.585 | (0.94) | |||

| 2. Rumination | 1.55 | 0.45 | 0.657 | −0.340 | 0.47*** | (0.95) | ||

| 3. SC | 1.89 | 0.52 | 0.714 | −0.243 | 0.46*** | 0.68*** | (0.87) | |

| 4. PLS | 3.39 | 0.44 | 0.348 | −0.157 | −0.31*** | −0.41*** | −0.48*** | (0.85) |

Note: N = 841; M = mean, SD = standard deviation; Numbers in parentheses denote Cronbach’s α. SOC = Stressors of COVID-19. SC = Stress consequences. PLS = Psychological support; *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

3.2. Testing for mediation effect

Hypothesis 1 assumed that rumination mediates the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequence. To test this hypothesis, we used Model 4 of the SPSS macro PROCESS complied by Hayes (2017). The regression results for testing mediation are reported in Table 2 . Results indicated that stressors of COVID-19 were positively related to rumination, which was, in turn, positively associated with stress consequences. The residual direct effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences remained positive. These results show that rumination partially mediated the association between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences (indirect effect = 0.280, SE = 0.022, 95% CI = [0.238, 0.326]), and the mediation effect accounted for 60.87% of the total effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 2.

Testing the mediation effect of SOC on SC.

| Model 1 (SC) |

Model 2 (Rumination) |

Model 3 (SC) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | t | β | t | β | t |

| SOC | 0.46 | 15.21*** | 0.47 | 15.53*** | 0.18 | 6.58*** |

| Rumination | 0.59 | 21.21*** | ||||

| R2 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.49 | |||

| F | 231.35*** | 241.21*** | 402.58*** | |||

Note: N = 841. Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. SOC = Stressors of COVID-19. SC = Stress consequences. PLS = Psychological support; ***p < 0.001.

3.3. Moderated mediation effect analysis

Hypothesis 2 proposed that the direct and indirect relationships between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences via rumination would be moderated by psychological support. To examine this moderated mediation model, we used Model 59 of PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2017). The results of parameters for three regression models are shown in Table 3 . Model 1 of Table 3 shows that the product (interaction term) of stressors of COVID-19 and psychological support had a significant negative association with rumination.

Table 3.

Testing the moderated mediation effect of SOC on SC.

| Model 1 (Rumination) |

Model 2 (SC) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | t | β | t |

| SOC | 0.37 | 12.37*** | 0.15 | 5.68*** |

| PLS | −0.32 | −10.35*** | −0.25 | −9.29*** |

| SOC × PLS | −0.12 | −4.34*** | −0.05 | −1.90 |

| Rumination | 0.48 | 16.25*** | ||

| Rumination × PLS | −0.08 | −2.65** | ||

| R2 | 0.32 | 0.54 | ||

| F | 129.04*** | 196.23*** | ||

Note: N = 841. Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column; SOC = Stressors of COVID-19, SC = Stress consequences, PLS = Psychological support; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

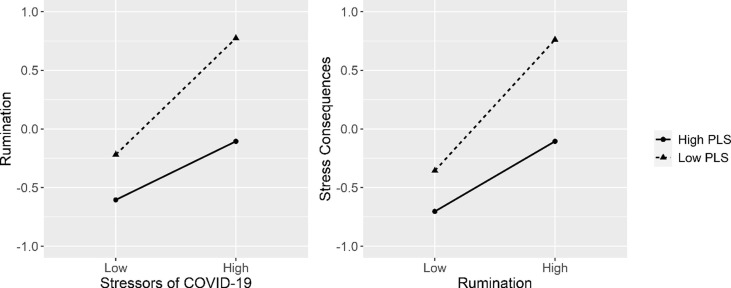

Following the methodology from a previous study (Wang et al., 2017), we plotted predicted rumination against stressors of COVID-19, separately for low and high levels of psychological support (one SD below the mean and one SD above the mean, respectively) (Fig. 2 ). Simple slope test demonstrated that for college students with high levels of psychological support, stressors of COVID-19 were positively associated with rumination, b simple = 0.25, p < 0.001. For college students with low psychological support, stressors of COVID-19 yielded a stronger positive association with rumination, b simple = 0.50, p < 0.001. Simple slope tests demonstrated that the higher the level of psychological support, the weaker the association between stressors of COVID-19 and rumination.

Fig. 2.

Interaction graphs for indirect paths. Note: PLS = Psychological Support.

Moreover, as Model 2 of Table 3 illustrates, the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences was significant, but this effect was not moderated by psychological support (p = 0.057). In addition, Model 2 of Table 3 also indicated that there was a significant main effect of rumination on stress consequences, and the product (interaction term) of rumination and psychological support had a significant negative association with stress consequence (p = 0.008), which suggests the effect of rumination on stress consequences was moderated by psychological support.

For a clear demonstration of the moderating role of psychological support, this study plotted the predicted stress consequences against rumination, separately for low and high levels of psychological support (one SD below and one SD above the mean, respectively; Fig. 2). Simple slope tests revealed that in both high and low levels of psychological support, rumination significantly correlated with stress consequence. However, the relation between rumination and stress consequences appeared to be stronger for those reporting low psychological support than those reporting high psychological support.

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap analysis further indicated that the indirect effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences through rumination was moderated by psychological support. Particularly, for college students low in psychological support, the indirect effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences via rumination was significant, b = 0.28, SE = 0.03, 95% CIboot = [0.22, 0.34]. The indirect effect was also significant for college students with high psychological support, but weaker, b = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CIboot = [0.06, 0.15]. Results indicate that rumination mediated the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences, but psychological support weakened the mediating effect of rumination. Because psychological support moderated the indirect effects, but not the direct effect, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

4. Discussion

While several empirical studies have shown the effect of stressors on stress consequences (Davey et al., 2016, Furuyashiki and Kitaoka, 2019, Gillespie et al., 2001, Lowe et al., 2017), the underlying mediating and moderating mechanisms remain less clear. Investigating the degree to which these underlying mechanisms of the stress consequences of college students under the pressure of COVID-19 is vitally important. The present study examined and proposed a novel moderated mediation model to test how stressors of COVID-19 generated harmful stress consequences, whether this relation was mediated by rumination, and how psychological may buffer the negative effects of COVID-19 stressors and rumination. Our results indicated that the impact of stressors of COVID-19 on stress consequences was significant and positive among Chinese college students, and this relation can be partially explained by heightened rumination. That is, stressors of COVID-19 increased rumination, which in turn, also increased stress consequences. Furthermore, the indirect relation was moderated by psychological support in the first and second stage of the mediation process. These two relations became weaker for college students with higher levels of psychological support.

4.1. The mediating role of rumination

Mediation results of this study suggested that rumination was not only an outcome of stressors of COVID-19 but also a partial catalyst for stress consequences. For the first stage of the mediation process (i.e., stressors of COVID-19 → rumination), this study indicated that stressors of COVID-19 promoted the activation of rumination mechanisms. This finding is in line with prior literature on rumination and stress consequences, whereby rumination tendencies are partly mutable in response to stressful life events (Li et al., 2019, Liu and Wang, 2017, Michl et al., 2013). Uncontrollable factors and stressors may create a dissonance between the ideal goal state and the reality state, leading to rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Indeed, those who have not learned proper emotion management strategies may be more sensitive to a perceived sudden lack of sense of control over their environment (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1995) given the impact that COVID-19 had on the current social ecology.

For the second stage of our mediation model (i.e., rumination → stress consequences), the present study found that rumination was associated with more stress consequences. Engaging in rumination may indeed lead college students to find themselves in a cycle of negative emotions and cognitions, thus making college students more susceptible to suffering stress consequences, such as anxiety (Liu & Wang, 2017), poorer sleep quality (Li et al., 2019), and depression (Michl et al., 2013). One may argue that COVID-19 stressors are unique from typical stressors; that is, because of the novelty of COVID-19, uncertainty shrouds any discussion or coverage of the pandemic and may make rumination over possible “what ifs” an unfortunate natural response among those affected. As our model shows, this may be particularly problematic given the rudimentary nature of rumination in leading to stress consequences.

It is also worth noting, however, that rumination only partially mediated the association between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences. That is, stressors of COVID-19 remained a significant, direct predictor of stress consequences even upon controlling for rumination. The remaining direct and positive association between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences may suggest that COVID-19 related stressors are uniquely salient risk factors that could significantly increase the prevalence of stress consequences. Thus, each of the separate paths in the mediation model was noteworthy and social interventions may be necessary at various stages of managing one’s COVID-19 stressors to mitigate susceptibility to stress consequences.

4.2. The moderating role of psychological support

Our findings also suggest that psychological support could moderate the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and rumination as well as the path between rumination and stress consequences. Both patterns were consistent with the risk buffer model (Masten, 2001) and showed that the adverse effects of stressors of COVID-19 on rumination and rumination on stress consequences were weaker in college students with high psychological support than in those with low psychological support. Psychological support may serve as a protective factor that mitigates the adverse effects of stressors of COVID-19 on rumination and rumination on stress consequences. There are two possible explanations for these findings. Firstly, after experiencing the stressors of COVID-19, psychological support can help college students shift their attention to positive things and reduce ruminant thoughts about negative events, thus acting as a buffer against rumination and protecting college students from stressors of COVID-19. Techniques specific to psychological support may be incorporated into conventional psychotherapy (e.g., Cognitive Behavior Therapy [CBT], Dialectical Behavior Therapy [DBT]) to assist more psychologically vulnerable populations (e.g., younger individuals) build the necessary resources to manage their stressors. Such interventions may be critical for reducing the psychological impact of COVID-19 (Ho, Chee, & Ho, 2020). Secondly, college students with higher psychological support have more psychological resources. Even with a higher tendency of rumination, these students experienced fewer stressful consequences due to the protective nature of having psychological support. Given the novelty of COVID-19, however, it is difficult to make definitive claims without a broader range of studies. Future studies may examine how proper provision of psychoeducation with accurate health information pertaining to COVID-19 for those who are psychologically impacted by the virus and its related outcomes (Tran, Dang, et al., 2020). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that for college students with high-levels of psychological support, the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and rumination as well as rumination and stress consequences remained significant. These suggest that despite the possible benefits of psychological support, college students may still be negatively impacted by the stressors stemming from COVID-19.

Contrary to our expectations, the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and stress consequences was not moderated by psychological support. This finding suggests that high stressors of COVID-19 are a salient risk factor for stress consequences among college students, and psychological support does not serve as a buffer against the adverse impact of high stressors of COVID-19. One possible explanation utilizing the Transactional Stress Process Model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) is that the stressors associated with COVID-19 may overload an individual, overburdening and exceeding their personal resources available to cope (Gellis, Kim, & Hwang, 2004). Because the stressors of COVID-19 may run high on the surface and be a chronic, salient threat, any dispositional psychological support may not be enough to prevent the onset of negative outcomes. Thus, while our results are promising, psychological support is not a catch-all solution in addressing the clear association of COVID-19 stressors and rumination to stress consequences. Rather, our results should be interpreted as indication of a possible starting area of social intervention during times of pandemics.

4.3. Implications

In order to help college students maintain proper mental health during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, government and health authorities may benefit from routine monitoring and measuring of student stress and related outcomes. Given the rampant ubiquity of misinformation floating social media, government and health authorities may also prioritize disseminating accurate information about COVID-19 and educating its populace about relying on trusted sources to reduce media-related stressors and prevent unnecessary stressors. As psychological support moderated the relation between stressors of COVID-19 and rumination as well as the path between rumination and stress consequences, future research may examine the efficacy of incorporating guided problem-solving strategies to help college students better understand and cope with their problems in an adaptive manner. Interventions that aim to improve students’ mood and confidence, develop their ability for help-seeking, and build their psychological resiliency may also yield positive results. As many colleges and universities contemplate opening campuses, administrators should monitor the mental health of their students and identify at-risk groups that may require additional interventions as the academic year progresses.

4.4. Limitations and future directions

Interpretation of the findings of this study must consider the following limitations. Firstly, the fact that this study is a cross-sectional survey study does not allow inference of causality. Future studies may examine longitudinal data as they become available to infer causality of the findings in this study. Secondly, the measures are based on a Chinese college student sample and the extent to which results may be generalizable to other cultural contexts or demographics is limited. Future studies may collect data from multiple informants (e.g., teacher, peer, or parent) across different cultures to further examine the robustness of our findings. Additionally, the current study did not collect information regarding students’ field of study nor socioeconomic status. Prior studies have identified both healthcare related fields of study and socioeconomic status to be relevant factors in COVID-19-related stress and behaviors (Tan et al., 2020, Tran et al., 2020) and future studies may incorporate this to examine how repeated exposure to minute details regarding the physiology of the virus may influence their stressors. Future studies may also examine the robustness of the model presented in this paper in other populations that may be exposed to qualitatively different COVID-19 stressors in both frequency and intensity (e.g., frontline healthcare workers). Lastly, while rumination in this study was conceptualized as being mutable in response to the advent of COVID-19, future studies may benefit from also examining the role of rumination as a moderating factor as COVID-19 stressors become chronic concerns in the long-term compared to being sudden negative life events.

5. Conclusion

Although further replication and extensions are needed, this study is an important step in unpacking how stressors of COVID-19 relate to stress consequences of Chinese college students. Because rumination served as one potential mechanism by which stressors of COVID-19 were associated with more stress consequences, it remains important to address rumination directly or intervene in a manner that reduces the impact of rumination on stress consequences. As many mental health counseling and clinical resources are spread thin, the need to examine social and psychological protective factors is becoming increasingly important. Our results on psychological support provide a promising step forward in examining how non-clinical interventions may help to mitigate the negative outcomes of COVID-19 stressors during these unique and unusual times.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Baojuan Ye: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Project administration. Dehua Wu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Data curation, Resources. Hohjin Im: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Software, Visualization, Resources. Mingfan Liu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Xinqiang Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Qiang Yang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105466.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R.P. Improving RLS diagnosis and severity assessment: Polysomnography, actigraphy and RLS-sleep log. Sleep Medicine. 2007;8:S13–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berset M., Elfering A., Lüthy S., Lüthi S., Semmer N.K. Work stressors and impaired sleep: Rumination as a mediator. Stress and Health. 2011;27(2):e71–e82. doi: 10.1002/smi.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouteyre E., Maurel M., Bernaud J.-L. Daily hassles and depressive symptoms among first year psychology students in France: The role of coping and social support. Stress and Health. 2007;23(2):93–99. doi: 10.1002/smi.1125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brosschot J.F., Gerin W., Thayer J.F. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;60(2):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz S., Stahlberg D. Can self-compassion improve sleep quality via reduced rumination? Self and Identity. 2018;17(6):666–686. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2018.1456482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Jin T., Wang T., Chen X. Violent exposure and social anxiety of college students: Mediating of ruminative responses. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2018;26(06):1200–1203. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Huang Y. Study on relationship between self-identity, peer stress and rumination thinking in college students. Occupation and Health. 2019;35(15):2115–2119. doi: 10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2019.0557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J.H.…Sharma V.K. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew Q.H., Wei K.C., Vasoo S., Chua H.C., Sim K. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: Practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Medical Journal. 2020;61(7):350–356. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A.L.S., Heitkemper M.M., Alencar G.P., Damiani L.P., Silva R.M.d., Jarrett M.E. Social support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life and resilience in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2017;40(5):352–360. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Mao T., Ye T., Lei B., Chen S.…Fan F. Effect of neuroticism on sleep quality of naval officers and soldiers: Moderated mediating effect. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;25(03):539–542. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davey C.G., López-Solà C., Bui M., Hopper J.L., Pantelis C., Fontenelle L.F., Harrison B.J. The effects of stress–tension on depression and anxiety symptoms: Evidence from a novel twin modelling analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46(15):3213–3218. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurosurveillance Editorial Team Note from the editors: World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(5):200131e. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyashiki T., Kitaoka S. Neural mechanisms underlying adaptive and maladaptive consequences of stress: Roles of dopaminergic and inflammatory responses. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2019;73(11):669–675. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis Z.D., Kim J., Hwang S.C. New York state case manager survey: Urban and rural differences in Job activities, job stress, and job satisfaction. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2004;31(4):430–440. doi: 10.1007/BF02287694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie N.A., Walsh M.H.W.A., Winefield A.H., Dua J., Stough C. Occupational stress in universities: Staff perceptions of the causes, consequences and moderators of stress. Work & Stress. 2001;15(1):53–72. doi: 10.1080/02678370110062449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella A.J., Moulds M.L. The impact of rumination on sleep quality following a stressful life event. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(6):1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., McIntyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;87:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Yang H. Chinese version of Nolen-Hoeksema ruminative responses scale (RRS) Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;17(05) doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2009.05.028. 550–551+549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa A., Yoshida T., Hattori Y., Nishimura H., Morimoto H., Tanno Y. Depressive Rumination and Social Problem Solving in Japanese University Students. J Cogn Psychother. 2015;29(2):134–152. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.29.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford Publications; 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200202-sitrep-13-ncov-v3.pdf?sfvrsn=195f4010_6 [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.S., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 2020;49(3):155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J., Gotlib I.H. Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24(2):281–298. doi: 10.1080/02699930903407948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent de Grey R.G., Uchino B.N., Trettevik R., Cronan S., Hogan J.N. Social support and sleep: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2018;37(8):787–798. doi: 10.1037/hea0000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Suh S. Social support as a mediator between insomnia and depression in female undergraduate students. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2019;17(4):379–387. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1363043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. The Guilford Press; New York: 2015. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Lau J., Yang X., Tsui H., Pang E., Wing Y. Positive mental health-related impacts of the SARS epidemic on the general public in Hong Kong and their associations with other negative impacts. Journal of Infection. 2006;53(2):114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44(1):1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S., Folkman S. Springer Publishing Company; 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gu S., Wang Z., Li H., Xu X., Zhu H., Deng S., Ma X., Feng G., Wang F., Huang J.H. Relationship between stressful life events and sleep quality: Rumination as a mediator and resilience as a moderator. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:348. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Zhang F., Wei C., Jia Y., Shang Z., Sun L., Wu L., Sun Z., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu W. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research. 2020;287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P. (2014). The Consequences of enterprise staff's pressure source on pressure effects: The mediation effect of optimistic personality. (Master's thesis, Anhui University).

- Liu W., Tian L. Progress on the relationship between rumination thinking and suicidal ideation. Chinese Journal of Public Health. 2013;29(11):1710–1712. doi: 10.11847/zgggws2013-29-11-47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.H., Wang W. Relationship between negative life events and state-anxiety: Mediating role of rumination and moderating role of self-affirmation. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2017;31(9):728–733. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2017.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe S.R., Joshi S., Galea S., Aiello A.E., Uddin M., Koenen K.C.…Cerdá M. Pathways from assaultive violence to post-traumatic stress, depression, and generalized anxiety symptoms through stressful life events: Longitudinal mediation models. Psychological Medicine. 2017;47(14):2556–2566. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl L.C., McLaughlin K.A., Shepherd K., Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(2):339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek J.B., Allen M.R. Social support as a moderator of day-to-day relationships between daily negative events and daily psychological well-being. European Journal of Personality. 2006;20(1):53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S., Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):115–121. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S., Wisco B.E., Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S., Wolfson A., Mumme D., Guskin K. Helplessness in children of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(3):377–387. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Patel V., Saxena S., Maj M., Maselko J., Phillips M.R., Rahman A. No health without mental health. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):859–877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M., Gao H. Acute psychological stress promotes general alertness and attentional control processes: An ERP study. Psychophysiology. 2020;57(4) doi: 10.1111/psyp.13521. 10.1111/psyp.v57.410.1111/psyp.13521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M.S., Alloy L.B. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and research. 2003;27(3):275–291. doi: 10.1023/A:1023914416469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skitch S.A., Abela J.R.Z. Rumination in response to stress as a common vulnerability factor to depression and substance misuse in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(7):1029–1045. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Jing M., Goh Y., Yeo L.L.L., Zhang K., Chin H.-K., Ahmad A., Khan F.A., Shanmugam G.N., Chan B.P.L., Sunny S., Chandra B., Ong J.J.Y., Paliwal P.R., Wong L.Y.H., Sagayanathan R., Chen J.T., Ng A.Y.Y., Teoh H.L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C., Sharma V.K. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(4):317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Zhang Z., Lai A., Ho R., Tran B., Ho C., Tam W. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;87:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B.X., Dang A.K., Thai P.K., Le H.T., Le X.T.T., Do T.T.T., Nguyen T.H., Pham H.Q., Phan H.T., Vu G.T., Phung D.T., Nghiem S.H., Nguyen T.H., Tran T.D., Do K.N., Truong D.V., Vu G.V., Latkin C.A., Ho R.C.M., Ho C.S.H. Coverage of health information by different sources in communities: Implication for COVID-19 epidemic response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(10):3577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B.X., Ha G.H., Nguyen L.H., Vu G.T., Hoang M.T., Le H.T., Latkin C.A., Ho C.S.H., Ho R.C.M. Studies of novel coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic: A global analysis of literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(11):4095. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran B.X., Vu G.T., Latkin C.A., Pham H.Q., Phan H.T., Le H.T., Ho R.C.M. Characterize health and economic vulnerabilities of workers to control the emergence of COVID-19 in an industrial zone in Vietnam. Safety Science. 2020;129:104811. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano K., Iijima Y., Tanno Y. Repetitive thought and self-reported sleep disturbance. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(4):779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedhara K., Shanks N., Anderson S., Lightman S. The role of stressors and psychosocial variables in the stress process: A study of chronic caregiver stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(3):374–385. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S., Rahman F.N.A., Wan Hasan W.M.H., Zamani I.Z., Arbaiei N.C., Khor S.L., Nawi A.M. Stressors in secondary boarding school students: Association with stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms: Stress in adolescents. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2013;5:82–89. doi: 10.1111/appy.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Choo F.N., Tran B., Ho R., Sharma V.K., Ho C. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;87:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Zhao M., Wang X., Xie X., Wang Y., Lei L. Peer relationship and adolescent smartphone addiction: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating role of the need to belong. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017;6(4):708–717. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Xu X., Wang H., Hu F., Jin C., Han B.…Li M. Relationship between trait anxiety and positive and negative affect in young male military personnel: Roles of rumination and educational lenel. Journal of Third Military Medical University. 2020;42(02):119–124. doi: 10.16016/j.1000-5404.201908051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Zhu A., Xu S., Xiang A., Bian C., Lu F.…Li M. Relationship between perceived stress and depression: Multiple mediating roles of reflection and brooding. Third Military Medical University. 2019;41(4):388–393. doi: 10.16016/j.1000-5404.201809102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020a). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-13, from World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report-13[R/OL].

- World Health Organization. (2020b). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-52, from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200312-sitrep-52-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=e2bfc9c0_4.

- Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China Medical science monitor. International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2020;26:e923549–e923551. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Zhang X. Development and preliminary application of college students psychological support scale. Modern Preventive Medicine. 2017;44(23):4301–4305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Zhu H., Zhang B., Cai T. Perceived social support as moderator of perfectionism, depression, and anxiety in college students. Social Behavior Personality. 2013;41(7):1141–1152. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2013.41.7.1141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.