Abstract

Radiotherapy is instrumental in the treatment of inoperable non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Studies have revealed that radiotherapy induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which consequently induces apoptosis and sensitization of cancer cells. A recent study has revealed that long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) CASC2 is negatively correlated with the malignancy of NSCLC cells. The present study investigated the effects and molecular mechanisms of CASC2 on radiosensitivity and ER stress in NSCLC cells. The overexpression of CASC2 markedly decreased cell survival and increased apoptosis, expression of PERK, phosphorylated-eIF2α and CHOP in irradiated human NSCLC cells, whereas knocking down PERK reversed these effects. Moreover, CASC2 considerably promoted the stability of PERK mRNA, but had no effect on the activity of PERK gene promoter in irradiated NSCLC cells. Strikingly, CASC2 exhibited no apparent effect on non-irradiated NSCLC cells. This study demonstrated that lncRNA CASC2 increases the stability of PERK mRNA, which consequently triggers the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP ER stress pathway and promotes radiosensitivity or apoptosis in irradiated NSCLC cells. Results of the present study suggest that CASC2 can act as an effective therapeutic target to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy in the treatment of NSCLC.

Keywords: Long non-coding RNA, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, PERK, eIF2α, CHOP, Non-small cell lung cancer, mRNA stability

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most prevalent cancer globally, with a high fatality rate (Ma et al. 2011). More than 80% of lung cancer cases are non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC) (He et al. 2016). The standard therapy for advanced NSCLC is radiation therapy (Yeo and Kim 2013). However, despite the progress in radiation technology, radiotherapy resistance is a critical factor that is limiting the therapeutic effect of radiation in NSCLC (Tang et al. 2016). Therefore, it is essential to explore the mechanisms of enhancing radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells.

A previous study revealed that endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is induced by radiotherapy of cancer cells (Saglar et al. 2014). Cumulative research has indicated that ER stress can induce apoptosis and enhance the sensitivity of tumor cells to radiotherapy (Yamamori et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2015), implying that ER stress can be a novel molecular target of ameliorating radiotherapy. ER is a subcellular structure that serves as a unique site for protein synthesis and folding (Walter and Ron 2011). Multiple physiological and pathological factors can trigger ER stress, which involves three primary mechanisms: (a) regulation of ER-associated protein translation through phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 α (eIF2α) by protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), (b) induction of endoplasmic chaperone and other modules to enhance the ability of proteins to fold, and (c) ER-related degradation to eliminate unfolded proteins in the ER. Persistence and intensification of ER stress trigger cell apoptosis via the ER stress pathway (Nishitoh 2012). PERK is an ER transmembrane protein kinase that suppresses protein synthesis by inhibiting the activity of eIF2α with phosphorylating serine. This causes increased expression of CHOP, a gene involved in growth arrest and induction of DNA damage (Hetz et al. 2011) (10). CHOP has a crucial function in apoptosis that occurs under endoplasmic reticulum stress (He et al. 2016; Nishitoh 2012).

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are noncoding RNAs that are longer than 200 nucleotides. Research conducted in the recent past has indicated that lncRNAs are essential in multiple cellular processes including gene regulation and cell differentiation (Kapranov et al. 2007; Yao et al. 2019). Previous studies have revealed that lncRNAs may have oncogenic or tumor-suppressing effects on NSCLC cells, and they regulate tumor development processes, such as cell proliferation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition, and apoptosis (Jiang et al. 2018; Li et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2017; Ricciuti et al. 2016; Shi et al. 2018). Recently, a novel lncRNA cancer susceptibility candidate 2 (CASC2) was identified and it was established that its expression is decreased in endometrial cancer (Baldinu et al. 2004). Furthermore, CASC2 suppresses malignancy in human gliomas (Wang et al. 2015). Remarkably, the expression of CASC2 is low in NSCLC and is associated with advanced TNM stage and tumor size, signifying that CASC2 may act as a novel target for NSCLC treatment (He et al. 2016).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect and the molecular mechanism of CASC2 on radiosensitivity and ER stress in NSCLC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and radiation treatment

Human NSCLC cell lines H23 (ATCC number CRL-5800) and H358 (ATCC number CRL-5807) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Beijing, China). Primary human bronchial epithelial cells (Cell Applications Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were grown in Bronchial/Tracheal Epithelial Cell Growth Medium (Cat. No. 511-500; Cell Applications Inc.). The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/mL of penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air. H23 and H358 cell lines were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. After culturing for 3 h, the cell lines were subjected to different doses of irradiation (2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy) using a linear accelerator Clinac 2100C (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 6 MV. A sham irradiation (0 Gy) was used as negative control.

Cell survival analysis

Cell survival was evaluated using colony formation assays. The H23 and H358 cells were seeded into six-well culture plates with 5 × 103 cells per well, and colony formation experiments conducted immediately after irradiation. After culturing cells for 10 days, cell colonies were fixed with 6.0% of glutaraldehyde, and stained with 0.5% of crystal violet. Cell survival was assessed by counting the number of colonies formed. Statistically significant difference in cell survival between the groups was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Cell transfection

LncRNA CASC2 or control lentiviral vector (Applied Biological Materials Inc., Richmond, BC, Canada) was co-transfected with psPAX2 and pMD2.G vectors into 293 T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (cat# 11668‐019; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After transfection into 293 T cells for 48 h, viral supernatant was collected after supercentrifugation and filtered using a 0.45 μm filter. The obtained lentiviruses were transfected into H23 and H358 cell lines together with 6 μg/mL of polybrene. After infection for 16 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium which contains 7 μg/mL of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and cells were cultured for another three days. The human PERK-shRNA lentiviral particles (Cat. No. sc-36213-V) and the shRNA negative control vectors (Cat. No. sc-108080) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA) and used to directly transduce H23 and H358 cells growing on 24-well plates, using Lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. After performing transient lentiviral transduction for 6 h, cells were subjected to subsequent analyses.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). A total of 1 μg RNA for each reaction was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). A PCR reaction system was constructed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Beijing, China). Real-time PCR was run on an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used: CASC2, 5′-GCACATTGGACGGTGTTTCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCAGTCCTTCACAGGTCAC-3′ (reverse); PERK, 5′-ATCCCCCATGGAACGACCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACCCGCCAGGGACAAAAATG-3′ (reverse); CHOP, 5′-GCCTTTCTCCTTTGGGACACTGTCCAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′- CTCGGCGAGTCGCCTCTACTTCCC-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-CCAGCAAGAGCACAAGAGGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGGTACATGACAAGGTGCGG-3′ (reverse). The procedure for real-time PCR was as follow: 95 °C for 20 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The PCR data were analyzed using 2−ΔΔCt method and the expression of GAPDH was used as the internal reference (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Determination of the stability of PERK mRNA

A total of 10 μg/ml of transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (Cat. No. SBR00013; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to pre-treat the cells (70–80% confluence) for 30 min. Cells were grown in media containing actinomycin D for 1, 2, and 4 h, respectively. Afterwards, the expression of PERK mRNA was detected by real-time PCR. Each experiment was repeated three independent times. Statistically significant difference in the expression of PERK mRNA between the groups was assessed by t test.

Western blotting

Proteins were isolated from cells and the concentration was measured by the Bio-Rad protein assay kit. A total of 20 μg protein extracts for each sample were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fuoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were subsequently incubated for 1 h with the following primary antibodies: anti-PERK (1:1000; Cat. No. sc-13973; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-eIF2α (1:1000; Cat. No. sc-30882; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phosphorylated eIF2α (1:1000; Cat. No. sc-101670; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti- GAPDH (1:1000; Cat. No. sc-32233; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membranes were then incubated for 1 h with the following secondary antibodies: bovine anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP), bovine anti-goat IgG-HRP and bovine anti-mouse IgG-HRP, which were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The protein bands were visualized using the ECL plus kit (GE Healthcare Inc., Shanghai, China). The western blots were analyzed using Image J software (NIH). Statistically significant difference in the proteins expressions between the groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Each experiment was repeated three independent times.

Luciferase reporter gene assay

The promoter of PERK gene was cloned into a luciferase reporter gene vector (Cat. No. S705088; SwitchGear Genomics, Shanghai, China). H23 and H358 cells stably transduced with human CASC2 lentivirus (LV-CASC2), nontransduced cells (NC) or blank control lentivirus (VC) were seeded in 96-well culture plates with a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and transfected with PERK gene promoter/luciferase reporter, using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Moreover, Plasmid PRL-CMV (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) encoding Renilla reniformis luciferase (at one fifth molar ratio to the reporter plasmid) was co-transfected with the reporter plasmid in each transfection as an internal control for data normalization. After culture for 24 h, cells were treated with irradiation at 0 Gy (sham irradiation) or 8 Gy with a linear accelerator operating at 200 cGy/minute and 6 MV. After irradiation for 24 h, the luciferase activity was determined using a LightSwitch Luciferase Assay Kit (Cat. No. LS010; SwitchGear Genomics) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The results were expressed as fold changes to that of NC at 0 Gy (designated as 1) and statistically significant difference in luciferase activity between the groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Three biological replicates were performed for each experiment.

Determination of cell apoptosis

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well. Cells were irradiated with a dose of 0 or 8 Gy at 6 MV after culturing for 3 h. Cell apoptosis was measured after 24 h of irradiation treatment using a microplate reader-based TiterTACS in situ apoptosis detection kit (catalog no., 4822-96-K; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocols (Zhu et al. 2015). Three biological replicates were performed for each experiment. Statistically significant difference in cell apoptosis between the groups was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and data represented as mean ± SD (standard deviations). SD was displayed as error bars on the graphs. A comparative analysis of more than two groups was executed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test, and comparisons between two groups were made using unpaired t test. P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CASC2 inhibits survival and promotes apoptosis in irradiated NSCLC cells

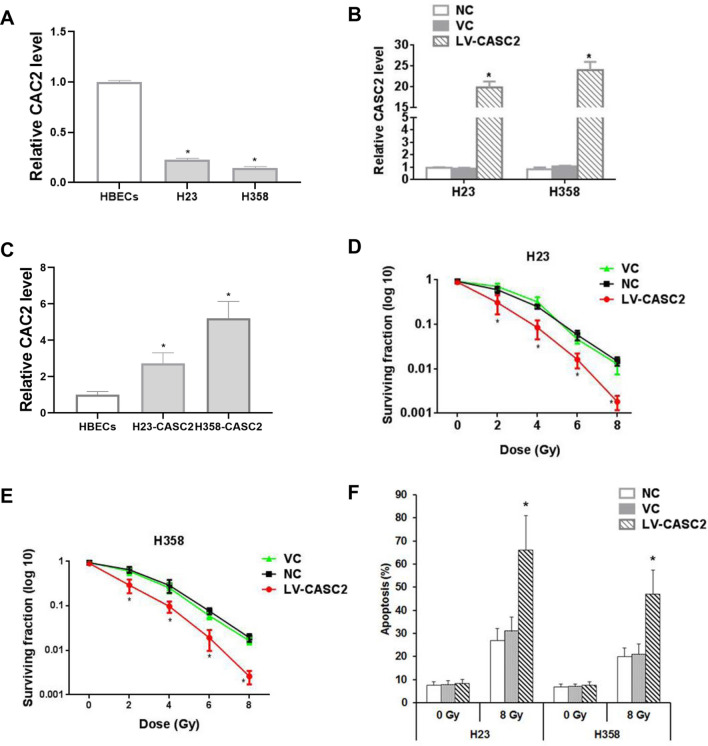

Strikingly, the expression of lncRNA CASC2 in human NSCLC cell lines H23 and H358 was markedly lower (about 15–20%) than that of the human bronchial epithelial cells (Fig. 1a). To explore the role of CASC2 in NSCLC, we constructed the two stable cell lines overexpressing CASC2. Stable lentiviral transduction of CASC2 caused significant overexpression of CASC2 in the NSCLC cells (approximately 17–20 fold of the constitutive levels, Fig. 1b). Since CASC2 was decreased in the NSCLC cells compared to the normal bronchial epithelial cells, we next investigated whether CASC2 level in the LV-CASC2-transfected NSCLC cells was up to that in the normal bronchial epithelial cells. By comparing the levels of re-introduced CASC2 in the NSCLC cell lines to that of HBECs, we confirmed that the reintroduction of CASC2 was to a physiologically-relevant level ((Fig. 1c). Overexpression of CASC2 considerably reduced the survival of cells treated with irradiation, implying that CASC2 can enhance the radiosensitivity of H23 and H358 cells (Fig. 1d, e). Moreover, CASC2 exhibited no remarkable effect on cell apoptosis in sham-irradiated cells, but under irradiation treatment, the high expression of CASC2 significantly increased cell apoptosis rate of H23 and H358 cell lines by over twofold (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

The role of CASC2 on survival and apoptosis of NSCLC cells in the presence or absence of irradiation. a Real-time PCR representing CASC2 expression levels in normal human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) and NSCLC cells H23 and H38. b The overexpression efficiency of CASC2 was verified by real-time PCR. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. c Real-time PCR representing CASC2 expression level in HBECs and NSCLC cell lines with overexpressed CASC2. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. d, e Colony-formation assay was used to evaluate the effect of CASC2 on cell survival under various irradiation doses. Colony-forming assays were performed immediately after irradiation. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. f The effect of CASC2 on apoptosis rate in H23 and H358 cell lines measured by TiterTACS in situ apoptosis detection kit, 24 h after irradiation at 0 Gy (sham irradiation) or 8 Gy. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. Nontransduced cells (NC) and cells stably transduced with the blank control lentivirus (VC) were used as controls. All experiments were repeated three times

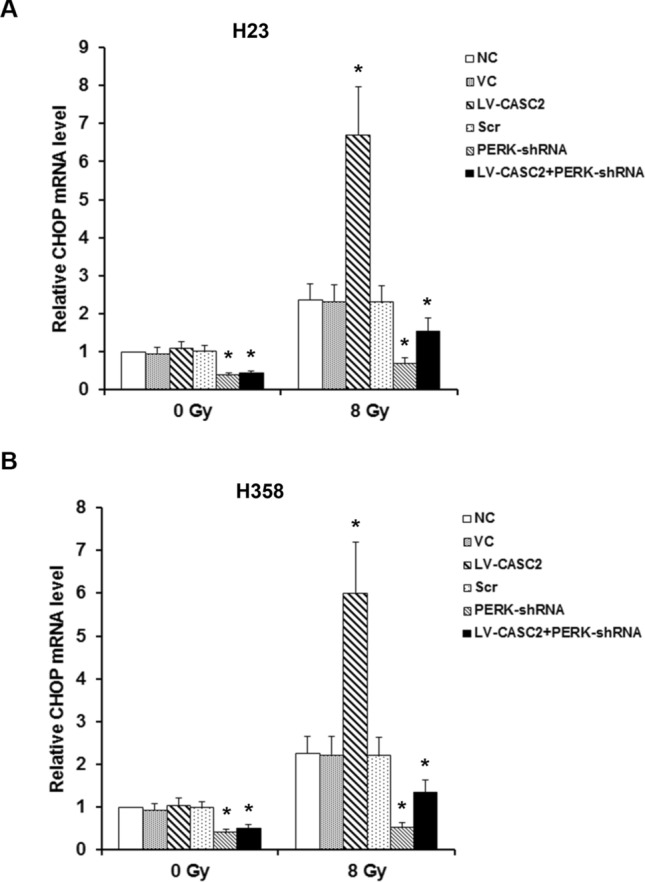

CASC2 triggers the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP pathway in irradiated NSCLC cells

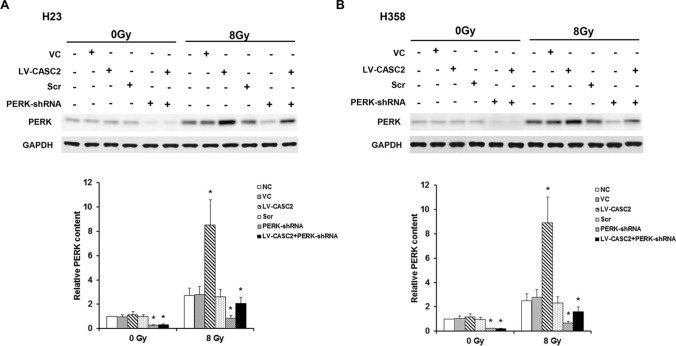

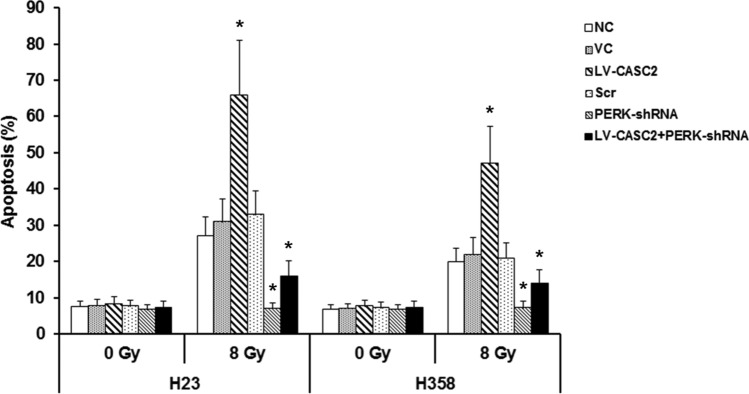

We next evaluated the effect of CASC2 on PERK signaling under the condition with and without irradiation, using western blot. Under sham irradiation, CASC2 had no significant effect on the protein expression of PERK in H23 and H358 cells lines, while CASC2 increased PERK protein levels by over threefold in irradiated H23 and H358 cells lines (Fig. 2). Moreover, with lentiviral transduction of PERK-shRNA, PERK deficiency significantly counteracted this effect (Fig. 2). Without irradiation, CASC2 failed to affect the phosphorylation of eIF2α at serine 51, which has been reported to be essential for PERK-induced inactivation of eIF2α (Walter and Ron 2011). Interestingly, CASC2 increased the phosphorylation of eIF2α by approximately 2.7–2.9-fold in the presence of irradiation (Fig. 3). Similar data trends were observed in CHOP (Walter and Ron 2011), a downstream effector molecule of PERK/eIF2α ER stress pathway and a stress-induced transcription factor that modulates the expression of genes associated with apoptosis (Fig. 4). Cumulatively, these data demonstrated that CASC2 induces the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP pathway in NSCLC cells under irradiation.

Fig. 2.

CASC2 modulates the expression of PERK in NSCLC cells under irradiation. a The expression of PERK in H23 cell lines determined by western blotting. b The expression of PERK in H358 cell lines determined by western blotting. Cells were stably transduced with LV-CASC2 (LV-CASC2) or transiently transduced with the PERK-shRNA lentivirus (PERK-shRNA), with the scramble shRNA lentivirus (Scr) as a control. Non-transduced cells (NC) and cells stably transfected with the blank vector (VC) were used as controls. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

Fig. 3.

CASC2 regulates the levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in NSCLC cells under irradiation. a Levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in H23 cell lines determined by western blotting. b Levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in H358 cell lines determined by western blotting. Cells were stably transduced with human CASC2 lentivirus (LV-CASC2). Non-transduced cells (NC) and cells stably transfected with a blank vector (VC) were used as controls. Cells stably transfected with LV-CASC2 were also transiently transduced with the PERK-shRNA lentivirus to knock down PERK, and cells transduced with the scrambled shRNA lentivirus used as control (Scr). One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

Fig. 4.

CASC2 modulates CHOP in NSCLC cells under irradiation. CHOP mRNA level was determined by real-time PCR in H23 cells (a) and CHOP mRNA level in H358 cells (b). One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

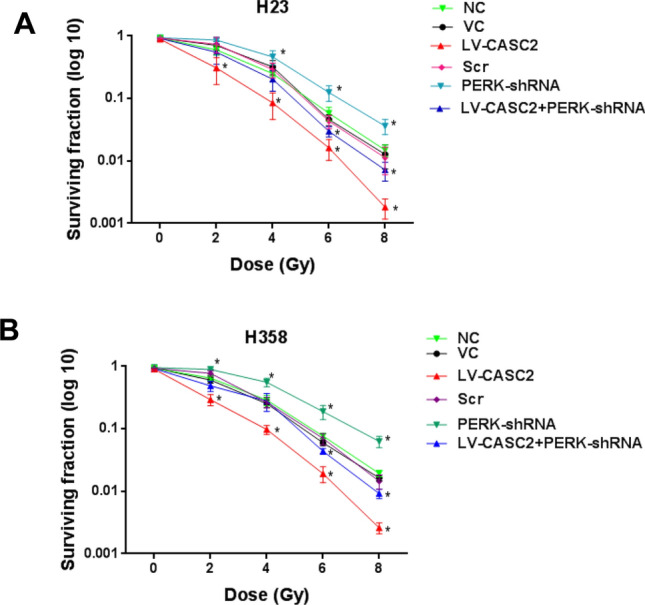

Effects of CASC2/PERK signaling on survival and apoptosis of irradiated NSCLC cells

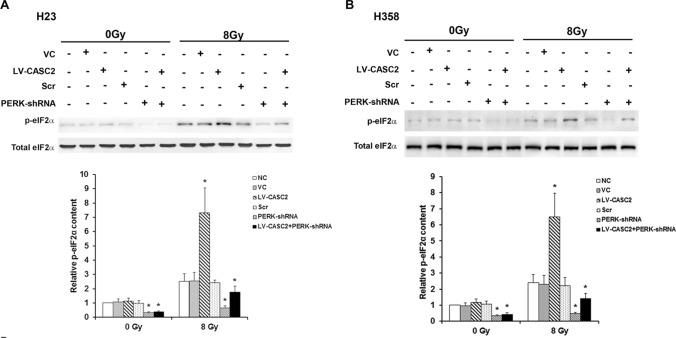

We further investigated whether CASC2 controls the survival and apoptosis of irradiated NSCLC cells by PERK signaling pathway. The overexpression of CASC2 and silencing of PERK exhibited no remarkable effect on apoptosis under sham irradiation, while in irradiated H23 and H358 cells, CASC2 increased the apoptosis by over twofold and this effect was reversed by silencing of PERK (Fig. 5). The CASC2-induced inhibition of cell survival was substantially counteracted by PERK deficiency under irradiation treatment (Fig. 6). Overall, these results indicated that CASC2 promotes apoptosis and radiosensitivity in irradiated NSCLC cells primarily through the PERK ER stress pathway.

Fig. 5.

Role of CASC2/PERK signaling in apoptosis of NSCLC cells under irradiation. Apoptosis in H23 and H358 cells was determined by TiterTACS in situ apoptosis detection kit, after 24 h of irradiation. Cells were treated with irradiation doses of 0 Gy or 8 Gy. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

Fig. 6.

Role of CASC2/PERK signaling in the survival of irradiated NSCLC cells. Colony-formation assays of a H23 cells and b H358 cells. Cells were treated with irradiation doses of 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy and Colony-forming assays were performed immediately after irradiation. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

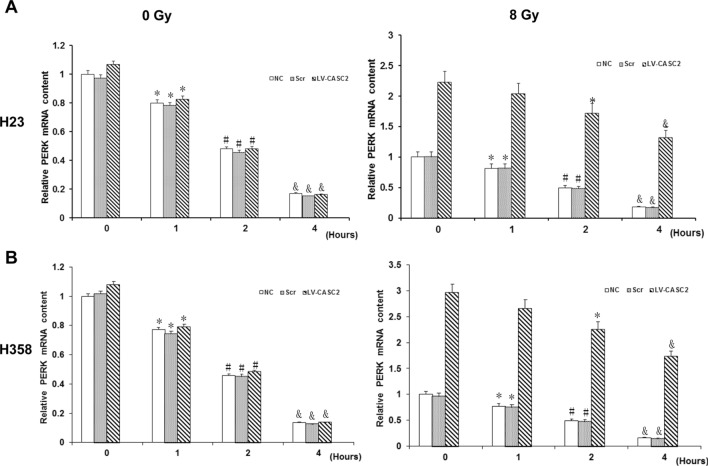

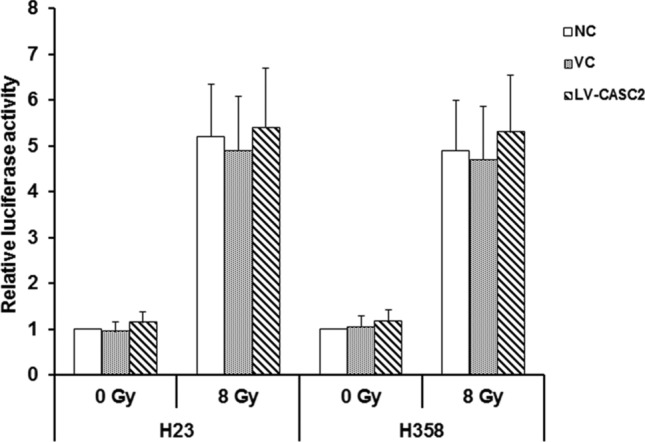

CASC2 promotes the stability of PERK mRNA in irradiated NSCLC cells

To explore the mechanism by which CASC2 regulates the PERK in NSCLC cells under irradiation, the H23 and H358 cells were first transfected by a luciferase reporter carrying the promoter of PERK. Notably, irradiation generally increased the activity of PERK gene promoter, whereas CASC2 did not have any effect on the fluorescence activity in the presence or absence of irradiation (Fig. 7). This indicates that CASC2 does not up-regulate the expression of PERK at the mRNA level. We further investigated the effect of CASC2 on the stability of PERK mRNA. In sham-irradiated H23 and H358 cells, CASC2 had no substantial effect on PERK mRNA levels with increase in the treatment time of actinomycin D (Fig. 8). Whereas, with irradiation, CASC2 markedly increased PERK mRNA levels, which decreased much more slowly than that in the controls with the increase of actinomycin D-treated time (Fig. 8). The PERK mRNA levels in irradiated cells as compared to the control levels (at 0 h of actinomycin D treatment) at 1, 2 and 4 h were decreased approximately 80%, 49% and 17%, respectively, in the controls, and 90%, 76% and 59%, respectively, in cells with CASC2 overexpression. These results indicated that CASC2 increased the levels of PERK mRNA in irradiated NSCLC cells primarily by enhancing PERK mRNA stability.

Fig. 7.

Role of CASC2 in the activity of the PERK gene promoter in NSCLC cells. Luciferase reporter gene assay was used to determine the function of CASC2 in the activity of PERK gene promoter in H23 and H358 cells. Cells were stably transduced with human CASC2 lentivirus (LV-CASC2). Non-transduced cells (NC) and cells stably transfected with a blank vector (VC) were used as controls. Cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids carrying the PERK gene promoter and then cultured for 24 h before treating cells with irradiation doses of 0 Gy or 8 Gy. One way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 vs NC. The experiment was repeated three times

Fig. 8.

Role of CASC2 in the stability of PERK mRNA of NSCLC cells. The mRNA level of PERK was measured by real-time PCR at 1, 2 and 4 h, respectively, after treatment with transcription inhibitor actinomycin D in a H23 cells and b H358 cells. Cells were treated with irradiation doses of 0 Gy (left panel) or 8 Gy (right panel) via linear accelerator Clinac 2100C operating at 200 cGy/minute and 6 MV. Immediately after irradiation, the cells were pre-treated with10 μg/ml of actinomycin D. *p < 0.05 vs 0 h; #p < 0.05 vs 1 h; &p < 0.05 vs 2 h. The experiment was repeated three times

Discussion

Lung cancer is the most prevalent cancer in both women and men, with a prevalence rate of 11.6% of all cancer cases. It is also a leading cause of cancer deaths, up to 18.4% of all cancer deaths (Bray et al. 2018). Radiotherapy significantly contributes to the effective treatment of inoperable NSCLC (Koh et al. 2012). Radiotherapy has been reported to induce ER stress, which consequently induces apoptosis and sensitivity of tumor cells to ionizing radiation (Saglar et al. 2014; Yamamori et al. 2013; Zhu et al. 2015). ER stress has been proven to be a potential target for cancer treatment. A previous study proposed the concept of targeting the UPR of ER, and discussed the potential of therapeutic intervention targeting the UPR of ER for cancer treatment (Nam and Jeon 2019). Small molecules or compounds that target ER and induce ER stress are proving to be potential anticancer drugs for subsequent generations (Banerjee and Zhang 2018). Furthermore, ER stress can act as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment (Clarke et al. 2014). Clinically, drugs that activate ER stress can be combined with radiotherapy to treat cancer. For example, dhalcomoracin has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation and increases sensitivity to radiotherapy in NSCLC by inducing ER stress (Zhang et al. 2020b). Phenethyl isothiocyanate in combination with Gefitinib induces apoptosis in NSCLC cells through ER stress-mediated Mcl-1 degradation (Zhang et al. 2020a). The present study revealed that CASC2 promoted apoptosis and radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells principally by enhancing the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP ER stress signaling pathway. Drugs targeting CASC2 may be a potential novel strategy for cancer treatment by modulating ER stress.

Research conducted in the recent past has demonstrated that CASC2 can acts as a tumor suppressed lncRNA in multiple tumors, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and pancreatic cancer (Wang et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019b). Furthermore, CASC2 has been demonstrated to enhance chemo-sensitivity of several cancers including sensitivity of cervical cancer to cisplatin, sensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma to TRAIL and sensitivity of prostate cancer to docetaxel (Feng et al. 2017; Gao et al. 2019; Jin et al. 2018). However, the effect of CASC2 on sensitivity of cancer to radiotherapy is still indeterminate. A study by He et al. (2016) revealed that CASC2 was remarkably down-regulated in NSCLC. This study established that the constitutive level of CASC2 in human NSCLC cell lines was lower than that in normal human bronchial epithelial cells, which is consistent with previous findings. Therefore, overexpression of CASC2 was used to evaluate the effect of CASC2 on NSCLC cells under irradiation. Notably, CASC2 alone had no significant effect on apoptosis in NSCLC cells, but it markedly decreased NSCLC cell survival and increased apoptosis under irradiation. These findings indicate that CASC2 can enhance sensitivity of NSCLC cells to irradiation, thereby promoting the therapeutic efficiency of irradiation-based treatment.

CASC2 significantly enhanced the expression of PERK in irradiated NSCLC cells. Conversely, CASC2 did not increase the expression of PERK in normal/sham-irradiated NSCLC cells, and this possibly explains why CASC2 had no significant apoptotic effect on the sham-irradiated cells. Strikingly, CASC2 did not significantly affect activity of the PERK gene promoter, but substantially enhanced the stability of PERK mRNA in the presence of irradiation, thereby explaining the CASC2-enhanced expression of PERK in irradiated NSCLC cells. LncRNAs can modulate genes in multiple ways, such as remodeling the chromatin, regulating RNA splicing, and competitively sponging microRNA (Gao et al. 2019; Hu et al. 2012). Cumulative research has revealed that lncRNAs bind to RNA-binding proteins, such as HuR, that modulates mRNA stability, thus promoting the stability of downstream mRNA (Wang et al. 2019). The molecular mechanisms by which CASC2 regulates the target gene have not been comprehensively studied. Previous studies revealed that CASC2 can increase mRNA level by directly binding to miRNA and inhibiting the expression of miRNA (Miao et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019a). Moreover, CASC2 directly binds to the protein of EIF4A3 and inhibits activation of the NF-κB pathway (Zhang et al. 2018). This study demonstrated that CASC2 significantly increased the expression levels of PERK and p-elF2α under an irradiation dose of 8 Gy and this can be attributed to the increase in the stability of PERK mRNA by CASC2. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which CASC2 increases the stability of PERK mRNA in irradiated NSCLC cells is still unknown. Thus, we intend to conduct further studies in the future to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

PERK, ATF6 and IRE1 are three vital stress sensors that promote adaptation to ER stress and restore normal ER functions (Walter and Ron 2011). PERK-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α triggers ER stress by regulating the translation of ER proteins (Nishitoh 2012). Intense ER stress can increase apoptosis and the sensitivity of cancer cells to irradiation (Nishitoh 2012). CHOP is a known effector of ER stress that can promote apoptosis after ER stress (Hetz et al. 2011). This study revealed that CASC2 increased the stability of PERK mRNA and upregulated the protein levels of PERK. In addition, CASC2 promoted phosphorylation of eIF2α, increased the expression of CHOP, and induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells under irradiation. The sensitivity of cells in which PERK was knocked down was not induced by irradiation-induced stress even under CASC2 overexpression. Therefore, CASC2 can promote irradiation-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cells by activating PERK-mediated eIF2α/CHOP ER stress.

In addition to irradiation, numerous chemicals/chemotherapeutic agents can induce ER stress in NSCLC cells (Colombo et al. 2016; Joo et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2015). Further studies should be conducted to investigate whether CASC2 can only enhance irradiation-induced ER stress/apoptosis, or it may also enhance other insults-induced ER stress/apoptosis in NSCLC cells. Moreover, CASC2 not only inhibits tumor development in endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer and gliomas but also inhibits tumor development in NSCLC(Baldinu et al. 2004; He et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2015), all of which can be managed by radiotherapy (Bodensohn et al. 2016; Carter et al. 2016; Colombo et al. 2016; He et al. 2016). Therefore, it will be imperative to examine whether CASC2 can enhance radiosensitivity in the other cancer cells.

Additionally, radiotherapy can induce response to DNA damage in cancer cells. CHOP is known as growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene, GADD153 (10). CASC2 can enhance the expression of CHOP signifying that CASC2 can promote irradiation-induced DNA damage in cancer cells by regulating CHOP. Thus, it will be essential to conduct future studies to investigate the effect and mechanisms of CASC2 in promoting irradiation-induced DNA damage in cancer cells. Nonetheless, this study had the following limitation: we only evaluated the survival of NSCLC cells within 24 h. Numerous studies have been conducted on the evaluation of irradiation on NSCLC cells within 24 h, such as investigations on the role of lncRNA PVT1 in radiosensitivity of NSCLC cells (Wu et al. 2017). In addition, a previous study revealed that high expression of CASC2 remarkably induced cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells (Zhang et al. 2019b). The present study revealed that CASC2 inhibited the survival of NSCLC cells, indicating that CASC2 can induce cell cycle arrest caused by irradiation in NSCLC. We intend to conduct further studies in the future to test these hypotheses.

Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that lncRNA CASC2 increases the expression of PERK in irradiated NSCLC cells by increasing the stability of PERK mRNA in vitro. This subsequently activates the PERK/eIF2α/CHOP ER stress signaling pathway and promotes radiosensitivity in irradiated NSCLC cells. Our findings suggest that CASC2 might act as a novel molecular therapeutic target to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy in NSCLC.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design, interpretation of the studies and analysis of the data and review of the manuscript. YY, ZD and JK conducted the experiments, YY supplied critical reagents, ZD carried out the data collection, analysis and interpretation, wrote the manuscript. JK participated in the experiment process, data collection and analysis.

Funding

The present study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grants #15A0106), Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence their work.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

All data is available by reasonable inquiry of the corresponding author by email.

References

- Baldinu P, et al. Identification of a novel candidate gene, CASC2, in a region of common allelic loss at chromosome 10q26 in human endometrial cancer. Hum Mutation. 2004;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/humu.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Zhang W. Endoplasmic reticulum: target for next-generation cancer therapy. ChemBioChem. 2018;19:2341–2343. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201800461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodensohn R, Corradini S, Ganswindt U, Hofmaier J, Schnell O, Belka C, Niyazi M. A prospective study on neurocognitive effects after primary radiotherapy in high-grade glioma patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:642–650. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0941-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R, et al. Radiosensitisation of human colorectal cancer cells by ruthenium(II) arene anticancer complexes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20596. doi: 10.1038/srep20596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HJ, Chambers JE, Liniker E, Marciniak SJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in malignancy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo N, et al. ESMO-ESGO-ESTRO Consensus Conference on Endometrial Cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:16–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, et al. Modulation of CASC2/miR-21/PTEN pathway sensitizes cervical cancer to cisplatin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2017;623–624:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W et al. (2019) Long non-coding RNA CASC2 regulates Sprouty2 via functioning as a competing endogenous RNA for miR-183 to modulate the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to docetaxel. Arch Biochem Biophys 665:69–78. htttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- He X, et al. Low expression of long noncoding RNA CASC2 indicates a poor prognosis and regulates cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:9503–9510. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Martinon F, Rodriguez D, Glimcher LH. The unfolded protein response: integrating stress signals through the stress sensor IRE1alpha. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1219–1243. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Alvarez-Dominguez JR, Lodish HF. Regulation of mammalian cell differentiation by long non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:971–983. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Chen A, Wu X, Zhou M, Ul Haq I, Mariyam Z, Feng Q. NEAT1 acts as an inducer of cancer stem cell-like phenotypes in NSCLC by inhibiting EGCG-upregulated CTR1. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4852–4863. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, et al. CASC2/miR-24/miR-221 modulates the TRAIL resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell through caspase-8/caspase-3. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:318. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo H et al (2016) c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway is critically involved in arjunic acid induced apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cells Phytother Res (PTR) 30:596–603. Htttps://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5563 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kapranov P, et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316:1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh PK, Faivre-Finn C, Blackhall FH, De Ruysscher D. Targeted agents in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): clinical developments and rationale for the combination with thoracic radiotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:626–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. Long non-coding RNA 1308 promotes cell invasion by regulating the miR-124/ADAM 15 axis in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6599–6609. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Wang Y, Liu X, Yan J, Su L. A novel derivative of tetrandrine (H1) induces endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis and prosurvival autophagy in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10403–10413. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Guo S, Su L. Chaetocin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress response and leads to death receptor 5-dependent apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2015;20:1499–1507. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, et al. Long non-coding RNA linc00673 regulated non-small cell lung cancer proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial mesenchymal transition by sponging miR-150-5p. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:118. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0685-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, et al. An integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expressions in non-small cell lung cancers. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao WJ, Yuan DJ, Zhang GZ, Liu Q, Ma HM, Jin QQ. lncRNA CASC2/miR18a5p axis regulates the malignant potential of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting RBBP8. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:1797–1806. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam SM, Jeon YJ (2019) Proteostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum: road to cure. Cancers 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nishitoh H. CHOP is a multifunctional transcription factor in the ER stress response. J Biochem. 2012;151:217–219. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciuti B, Mencaroni C, Paglialunga L, Paciullo F, Crino L, Chiari R, Metro G. Long noncoding RNAs: new insights into non-small cell lung cancer biology, diagnosis and therapy. Med Oncol. 2016;33:18. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saglar E, Unlu S, Babalioglu I, Gokce SC, Mergen H. Assessment of ER stress and autophagy induced by ionizing radiation in both radiotherapy patients and ex vivo irradiated samples. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2014;28:413–417. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, et al. Long noncoding RNA PCAT6 functions as an oncogene by binding to EZH2 and suppressing LATS2 in non-small-cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine. 2018;37:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, et al. Radiation-induced miR-208a increases the proliferation and radioresistance by targeting p21 in human lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (CR) 2016;35:7. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Liu YH, Yao YL, Li Z, Li ZQ, Ma J, Xue YX. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 suppresses malignancy in human gliomas by miR-21. Cell Signal. 2015;27:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through CASC2/miR-367/FBXW7 axis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:123. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, et al. Long noncoding RNA EGFR-AS1 promotes cell growth and metastasis via affecting HuR mediated mRNA stability of EGFR in renal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:154. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Li Y, Zhang H, Hu X. Knockdown of Lncrna PVT1 enhances radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer by sponging Mir-195. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:2453–2466. doi: 10.1159/000480209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamori T, Meike S, Nagane M, Yasui H, Inanami O. ER stress suppresses DNA double-strand break repair and sensitizes tumor cells to ionizing radiation by stimulating proteasomal degradation of Rad51. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3348–3353. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao RW, Wang Y, Chen LL. Cellular functions of long noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:542–551. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo SG, Kim ES. Efficient approach for determining four-dimensional computed tomography-based internal target volume in stereotactic radiotherapy of lung cancer. Radiat Oncol J. 2013;31:247–251. doi: 10.3857/roj.2013.31.4.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Liang S, Zhou Y, Li S, Li Y, Liao W. HNF1A/CASC2 regulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation through PTEN/Akt signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:2816–2827. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Leng T, Zhang Q, Zhao Q, Nie X, Yang L. Sanguinarine inhibits epithelial ovarian cancer development via regulating long non-coding RNA CASC2-EIF4A3 axis and/or inhibiting NF-kappaB signaling or PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Biomed Pharmacother Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;102:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhu M, Sun Y, Li W, Wang Y, Yu W (2019) Upregulation of lncRNA CASC2 suppresses cell proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer via inactivation of the TGF-beta. Signal Pathway Oncol Res 27:379–387. htttps://doi.org/10.3727/096504018X15199531937158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, et al. Long non-coding RNA CASC2 upregulates PTEN to suppress pancreatic carcinoma cell metastasis by downregulating miR-21. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:18. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0728-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Chen M, Cao L, Ren Y, Guo X, Wu X, Xu K. Phenethyl isothiocyanate synergistically induces apoptosis with Gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated degradation of Mcl-1. Mol Carcinogen. 2020;59:590–603. doi: 10.1002/mc.23184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SR, et al. Chalcomoracin inhibits cell proliferation and increases sensitivity to radiotherapy in human non-small cell lung cancer cells via inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated paraptosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2020;41:825–834. doi: 10.1038/s41401-019-0351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Abulimiti M, Liu H, Su XJ, Liu CH, Pei HP. RITA enhances irradiation-induced apoptosis in p53-defective cervical cancer cells via upregulation of IRE1alpha/XBP1 signaling. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1279–1288. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.