Abstract

Background

Patients with malignant gliomas have a poor prognosis. However, little is known about patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of the prognosis and the primary treatment goal.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study in patients with newly diagnosed malignant gliomas (N = 72) and their caregivers (N = 55). At 12 weeks after diagnosis, we administered the Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire to assess understanding of prognosis and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to evaluate mood. We used multivariable regression analyses to explore associations between prognostic understanding and mood and McNemar tests to compare prognostic perceptions among patient-caregiver dyads (N = 48).

Results

A total of 87.1% (61/70) of patients and 79.6% (43/54) of caregivers reported that it was “very” or “extremely” important to know about the patient’s prognosis. The majority of patients (72.7%, [48/66]) reported that their cancer was curable. Patients who reported that their illness was incurable had greater depressive symptoms (B = 3.01, 95% CI, 0.89-5.14, P = .01). There was no association between caregivers’ prognostic understanding and mood. Among patient-caregiver dyads, patients were more likely than caregivers to report that their primary treatment goal was cure (43.8% [21/48] vs 25.0% [12/48], P = .04) and that the oncologist’s primary goal was cure (29.2% [14/48] vs 8.3% [4/48], P = .02).

Conclusions

Patients with malignant gliomas frequently hold inaccurate perceptions of the prognosis and treatment goal. Although caregivers more often report an accurate assessment of these metrics, many still report an overly optimistic perception of prognosis. Interventions are needed to enhance prognostic communication and to help patients cope with the associated distress.

Keywords: caregiver, illness perceptions, malignant glioma, prognostic awareness, treatment goal

Although patients with malignant gliomas often have a poor prognosis, there is an inadequate understanding of these patients’ and their caregivers’ perceptions of their prognosis and treatment goals. Among patients with advanced solid tumors, most patients report wanting to know as much as possible about their prognosis.1–3 Yet, more than half of patients with advanced solid tumors have an overly optimistic perception of their prognosis and the goal of treatment.1,4 Data demonstrate that patient-clinician communication about prognosis leads to greater prognostic awareness in patients with advanced cancer.5–7 Importantly, patients with advanced cancer who are aware of their prognosis are less likely to prefer aggressive treatment or life-extending therapies at the end of life.7–11 However, prior studies have shown that more accurate prognostic understanding may be associated with greater depressive and/or anxiety symptoms in patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers.1,12,13 Although this prior research has provided important insight into prognostic understanding in patients with advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignances, very few studies have specifically assessed these perceptions among patients with gliomas or their caregivers, and the limited available data suggest that this population may similarly hold inaccurate perceptions about prognosis.14–16

In this prospective study, we sought to evaluate information preferences of patients with newly diagnosed malignant gliomas and their caregivers, their understanding of their prognosis, and treatment goal. We explored associations between patients’ and caregivers’ prognostic understanding and their mood. We also compared patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of prognosis and treatment goal among patient-caregiver dyads.

Methods

Study Procedures

The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this study prior to its initiation. From January 18, 2016 through March 16, 2018, we enrolled 100 patients with a malignant glioma and 82 caregivers in the ambulatory care setting. We identified and recruited consecutively eligible patients and their caregivers by screening the brain tumor clinic weekly outpatient schedule. We obtained permission from the patient’s oncologist prior to approaching the patient and/or caregiver. Participants provided written informed consent. We extracted information about the patient’s diagnosis, including tumor type and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutation status from the electronic health record.

Participants

Patients were eligible to enroll in this study if they were receiving their primary cancer care at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, were within 6 weeks of diagnosis of a malignant glioma as documented in the pathology report in the electronic health record (glioblastoma, anaplastic astrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, high-grade glioma not otherwise specified), age 18 years or older, able to read and write in English, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2, had no known psychiatric or cognitive disorder that would preclude them from providing informed consent, and had a Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) score greater than 25 documented in the medical record. For patients with no previously documented score, the MMSE was performed by a trained member of the clinical or research team to confirm eligibility. Each patient who provided consent to participate in the study was asked to identify a relative or friend as his or her primary caregiver. Eligible caregivers were age 18 years or older, able to read and respond to questions in English, and required to either live with the patient or have in-person contact with the patient at least twice per week. Patients were permitted to participate without an enrolled caregiver. Additionally, participating caregivers were permitted to stay in the study if their loved ones became unable to participate.

Study Measures

Enrolled patients and caregivers completed baseline demographic questionnaires detailing their age, sex, race, ethnicity, religion, relationship status, educational level, annual household income, and living situation. At 12 weeks after enrollment (± 4 weeks), patients and caregivers completed questionnaires to assess their information preferences, understanding of their prognosis, treatment goal, and mood. We administered questionnaires at scheduled clinic visits or sent questionnaires by mail or secure electronic communication (ie, encrypted email messages) to participants with no scheduled visit during that time period.

We administered the Prognosis and Treatment Perceptions Questionnaire (PTPQ) to assess patients’ and caregivers’ beliefs about the likelihood of cure, importance of knowing about prognosis, frequency of conversations with their oncologists about prognosis, perceptions of the goal of cancer treatment, and prognostic awareness (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). This questionnaire has been widely used to investigate perceptions of prognosis and expectations of patients with cancer, including those with brain tumors.1,12,15,17 Each item on the PTPQ is scored individually. We assessed responses to the question “How important is it for you (your loved one) to know about the likely outcome of your (their) cancer over time?” with options ranging from “extremely important” to “not at all important.” We also examined patients’ and caregivers’ responses to the question “How often have you (your loved one) had a conversation with your (their) oncologist about the likely outcome of your (their) cancer over time?” with options ranging from “very often” to “never.” We evaluated prognostic understanding using the item “How likely do you think it is that you (your loved one) will be cured of cancer?” with responses ranging from “extremely likely (more than a 90% chance of cure),” to “no chance (0% chance of cure).” Per prior research, we grouped responses into 2 categories, with responses of “very unlikely (less than 10% chance of cure)” or “no chance (0% chance of cure)” considered “incurable,” and all other responses considered “curable.” 1 We also analyzed participants’ responses to the question “How would you describe your (your loved one’s) current medical status?” with choices of “relatively healthy,” “relatively healthy and terminally ill,” “seriously ill and not terminally ill,” and “seriously ill and terminally ill.” Consistent with prior studies, we grouped the responses into 2 categories: “terminally ill” or “not terminally ill.” 1,12 Participants were asked to identify their (loved one’s) primary goal of their current cancer treatment as well as their oncologist’s primary goal from the following options: “to lessen their suffering as much as possible,” “for them and/or their family to be able to keep hoping,” “to make sure they have done everything,” “to extend their life as long as possible,” “to cure their cancer,” “to help cancer research,” and “other.” We grouped responses into primary treatment goal of “to cure my (their) cancer” vs all other responses.1,12,17

We administered the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to assess symptoms of depression and anxiety in all study participants (patients and caregivers). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a validated questionnaire used extensively in samples of patients with cancer and their caregivers, and contains two 7-item subscales assessing depressive and anxiety symptoms during the past week.18 Scores on each subscale range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater depressive or anxiety symptoms.18–20

Statistical Analyses

We performed all analyses using SAS version 9.4 software. We used descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and ranges for continuous variables to summarize patients’ and caregivers’ baseline characteristics. We described patients’ and caregivers’ preferences for information about prognosis and their perceptions about the likely outcome of the cancer (curable vs incurable) and the patient’s current medical status (terminally ill vs not terminally ill). We reported all available case analyses without accounting for missing data, given the descriptive nature of the study. Denominators vary between specific questions because some participants did not answer all questions on their study survey. We performed multivariable linear regression analyses to examine the associations between prognostic understanding and mood both for patients and caregivers, controlling for age and sex, given their potential confounding effect on the relationship between prognostic understanding and mood.21–23 Additionally, we performed Fisher exact tests to explore the impacts of education level, religion, tumor grade, and IDH status on patients’ perception of curability and terminally ill status. We used McNemar tests to compare perceptions about prognosis and treatment goal in patient-caregiver dyads. We used a significance level of .05 for all comparisons.

Results

Participants

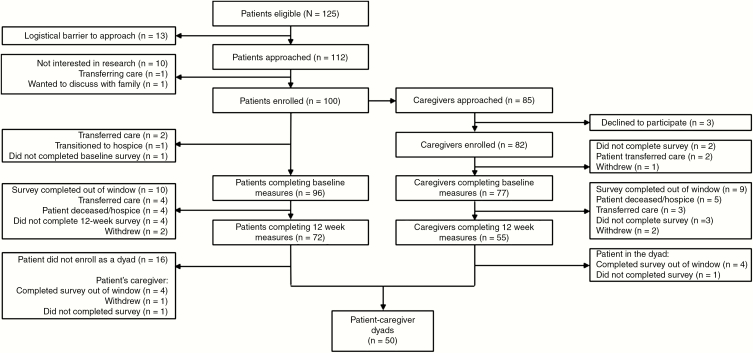

We identified 125 eligible patients (Fig. 1), and approached 112 for study participation. We enrolled 89.3% (100/112) of those approached to participate in the study. Of the 100 patient participants, 85 had eligible caregivers, of whom 96.5% (82/85) agreed to participate in the study. Seventy-two patients and 55 caregivers completed both baseline demographics and 12-week questionnaires. Denominators vary among analyses because some participants did not answer all questions on their study survey. Table 1 displays patient and caregiver sociodemographic characteristics. The mean age of patients was 56.2 years and the mean age of caregivers was 52.9 years. The majority of patients and caregivers were white and non-Hispanic, and most caregivers were female and the spouse of the patient. The most common diagnosis among patients was IDH wild-type glioblastoma.

Fig. 1.

Flow Diagram of Patient and Caregiver Recruitment

Table 1.

Patient and Caregiver Baseline Characteristics

| Patients (n = 72) | Caregivers (n = 55) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range), y | 56.2 (24-82) | 52.9 (23-82) |

| Sex, female (n, %) | 23 (31.9%) | 43 (78.2%) |

| Race (n, %) | ||

| White | 66 (91.7%) | 51 (92.7%) |

| Asian | 3 (4.2%) | 3 (5.5%) |

| Other | 3 (4.2%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 65 (90.3%) | 52 (94.6%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Unspecified | 6 (8.3%) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Income | ||

| Less than or equal to $50 000 | 8 (11.1%) | |

| $51 000-$100 000 | 18 (25.0%) | |

| Greater than $150 000 | 41 (56.9%) | |

| Not disclosed | 5 (6.9%) | |

| Education | ||

| 11th grade or less | 1 (1.4%) | – |

| High school graduate or GED | 11 (15.3%) | 12 (21.8%) |

| 2 years of college/AA degree/Technical school training | 12 (16.7%) | 15 (27.3%) |

| College graduate (BA or BS) | 22 (30.6%) | 15 (27.3%) |

| Graduate degree | 26 (36.1%) | 13 (23.6%) |

| Diagnosis (n, %) | ||

| Glioblastoma | 53 (73.6%) | |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 17 (23.6%) | |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | 1 (1.4%) | |

| High-grade glioma, NOS | 1 (1.4%) | |

| IDH mutation status | ||

| IDH wild type | 53 (73.6%) | |

| IDH mutant | 19 (26.4%) | |

| CG relationship to patient (n, %) | ||

| Spouse | 46 (83.6%) | |

| Child | 5 (9.1%) | |

| Sibling | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Parent | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Other | 2 (3.6%) |

Abbreviations: AA, associate in arts; BA, bachelor of arts; BS, bachelor of science; CG, caregiver; GED, General Educational Development; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Patient Prognostic Understanding

In our analyses of all participants, patients reported wanting to know as much as possible about their illness, with 87.1% (61/70) of patients stating it was “very ” or “extremely” important to know about the likely outcome of their cancer over time. However, only 19 of 70 patients (27.1%) reported that they discussed their prognosis with their oncologist “often” or “very often,” with the remainder reporting only infrequently having these conversations. The majority of patients (48/66, 72.7%) reported that their cancer was curable, and 40 of 67 patients (59.7%) described themselves as not terminally ill. There were no significant differences in prognostic understanding between patients with World Health Organization grade III tumors vs those with World Health Organization grade IV tumors, nor between patients with IDH-mutant gliomas vs IDH wild-type gliomas. In addition, prognostic awareness was not significantly associated with performance status in the study population, and we found no significant differences in perception by religion or level or education.

In multivariable analyses, patients who reported that their illness was incurable had greater depressive symptoms compared with those who perceived their cancer as curable (B = 3.01, 95% CI, 0.89-5.14, P = .01) (Table 2). Similarly, patients who reported that they were terminally ill had greater depressive symptoms than those who reported that they were not terminally ill (B = 2.41, 95% CI, 0.48-4.34, P = .02). Patients’ anxiety symptoms were not significantly associated with their perception of likelihood of cure or their assessment of their current medical status. Neither age nor sex were significantly associated with depression or anxiety scores at 3 months. Although we controlled for age and sex given their effect on mood in prior studies of patients with cancer, neither age nor sex contributed significantly to the models in our study population.

Table 2.

Association Between Patient Mood and Perception of Prognosis and Medical Status

| Difference in mean score, Ba | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HADS–Depression Score | |||

| Perceived likelihood of cure | .01 | ||

| Incurable | 3.01 | (0.89 to 5.14) | |

| Curable | (Reference) | ||

| Assessment of current medical status | .02 | ||

| Terminally ill | 2.41 | (0.48 to 4.34) | |

| Not terminally ill | (Reference) | ||

| HADS–Anxiety Score | |||

| Perceived likelihood of cure | .07 | ||

| Incurable | 1.73 | (–0.17 to 3.62) | |

| Curable | (Reference) | ||

| Assessment of current medical status | .20 | ||

| Terminally ill | 1.13 | (–0.60 to 2.86) | |

| Not terminally ill | (Reference) |

Abbreviation: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

aAll models adjusted for age and sex.

Caregiver Prognostic Understanding

Caregivers also reported that it was important for their loved ones to know as much as possible about their illness, with 79.6% (43/54) of all participating caregivers stating that it was “very” or “extremely” important for their loved one to know about the likely outcome of their cancer over time. Yet, only 20.4% (11/54) of caregivers reported that their loved one had discussed prognosis with their oncologist “often” or “very often.” Only 44.2% (23/52) of caregivers acknowledged that their loved one’s illness was incurable, although the majority of caregivers (55.8% [29/52]) reported that their loved one was terminally ill. In multivariable analyses, there was no significant association between caregivers’ mood symptoms and their assessment of their loved ones’ medical status or perception about likelihood of cure.

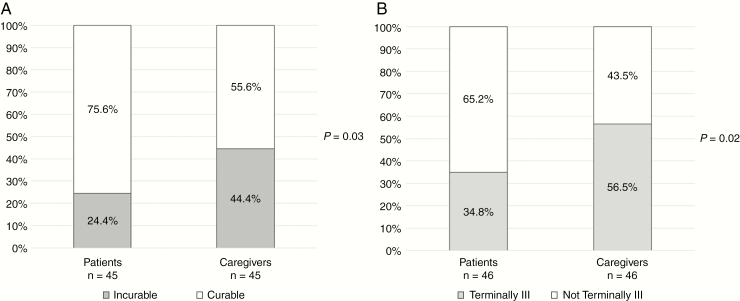

Patient-Caregiver Dyads Prognostic Understanding

We compared patients’ and caregivers’ prognostic understanding among 50 patient-caregiver dyads (Fig. 2). Denominators vary among analyses according to how many pairs completed the given question. Patients were significantly more likely than caregivers to report that the cancer was curable (75.6% [34/45] vs 55.6% [25/45], P = .03). Similarly, patients were less likely than caregivers to report that they were terminally ill (34.8% [16/46] vs 56.5% [26/46], P = .02).

Fig. 2.

Patients’ and Caregivers’ Perceptions About Prognosis.

A, Perceived likelihood of cure. In dyadic analyses, significantly more patients than caregivers report that their cancer is curable. B, Assessment of current medical status. Significantly more caregivers than patients report that the patient is terminally ill.

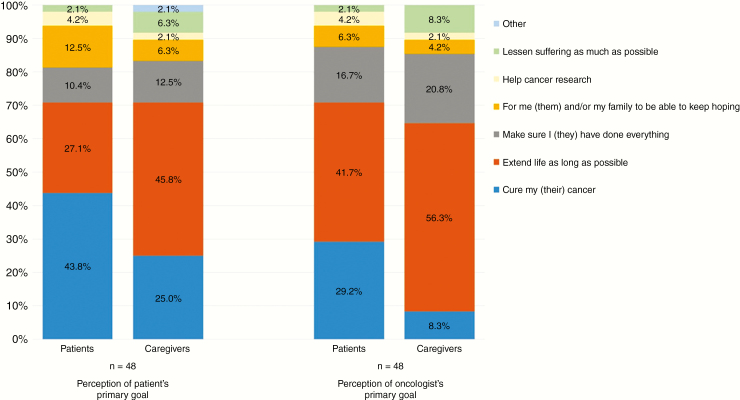

We also compared patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions regarding the patient’s primary treatment goal and their perceptions regarding the oncologist’s primary treatment goal (Fig. 3). Among dyads, patients were more likely than caregivers to report that their primary treatment goal was cure (43.8% [21/48] vs 25.0% [12/48], P = .04) and that the oncologist’s primary goal was cure (29.2% [14/48] vs 8.3% [4/48], P = .02).

Fig. 3.

Perceptions of Patient’s Primary Treatment Goal and Oncologist’s Primary Treatment Goal Patients more commonly report that their primary treatment goal is to cure their cancer, in comparison with caregivers’ perception of the primary goal. Patients also more frequently report their oncologist’s primary treatment goal is to cure their cancer, compared with caregivers.

Discussion

In this study, we found that although most patients with newly diagnosed malignant gliomas and their caregivers wanted information about their prognosis, they frequently had an inaccurate appreciation of the low likelihood of being cured of their cancer, with more than 70% of patients and more than 50% of caregivers reporting that their (loved one’s) cancer had a 10% or greater chance of being cured. This is particularly striking because the majority of patient participants carried the diagnosis of an IDH wild-type glioblastoma, and thus had a median expected survival of less than 2 years from the time of diagnosis. Of note, patients and caregivers reported infrequent conversations about prognosis with their oncologists. However, it remains unclear whether these conversations were truly infrequent or inadequate, or whether participants simply did not recall these discussions. Prior patient-clinician communication studies have shown that even when conversations about prognosis occur, patients may not accurately recall them, particularly when these discussions have high emotional content.24–26 Furthermore, the PTPQ does not specifically assess how often patients and caregivers want to have conversations about prognosis, so it remains unclear whether the frequency of these conversations matches patient and caregiver preferences. Our results highlight the need for further investigation into communication about prognosis between patients with malignant gliomas, their caregivers, and their oncologists. This may ultimately lead to the identification of barriers to communication and interventions to support more timely and/or effective communication about prognosis for patients with malignant gliomas, because such interventions have proven beneficial in other advanced cancer populations.27–30

Notably, we found that although patients reported wanting to know about their prognosis, patients who reported that their illness was incurable or that they were terminally ill had greater depressive symptoms. Although we are unable to assess the directionality of this association, these results suggest that efforts to promote conversations about prognosis in this population must take into account the potential psychological implications of perceptions about prognosis. More robust support systems are needed to address the psychological distress experienced by patients with malignant gliomas in coping with the terminal nature of their illness.

We also identified significant discordance between patients with malignant gliomas and their caregivers with respect to their prognostic understanding as well as their perceptions regarding the patients’ primary treatment goal and the oncologists’ primary treatment goal. In comparison with their caregivers, patients more frequently reported that their own goal and/or their oncologist’s goal was to cure their cancer. The reasons for this discordance remain unclear. It is possible that patients are more likely than their caregivers to report their hope or wish for a cure rather than their assessment of the intended goal of their cancer treatment. Importantly, data suggest that when patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers have a concordant appreciation of their poor prognosis, they are more likely to complete “do not resuscitate” orders and to enroll in hospice.31,32 Thus, understanding and addressing the drivers of the discordant perceptions of patients with malignant gliomas and their caregivers might have important implications for end-of-life decision making in this population. Furthermore, such understanding could enable clinicians and caregivers to ensure that treatment decisions throughout the disease course match the patient’s goals and wishes, resulting in better patient mood and quality of life, and improvement in mood and subsequent bereavement adjustment for their caregivers.7,8,33

There are several limitations of our study. First, this study was conducted at a single academic medical institution serving a relatively homogeneous patient population. The limited racial and socioeconomic diversity of our patient and caregiver sample limits the generalizability of the results. Second, the small sample size at the selected time point and differences in the number of respondents to each PTPQ question may have limited our ability to detect meaningful differences between groups. Third, because the analyses were conducted at a single time point, we were unable to assess the directionality or causality of the observed relationship between patients’ depressive symptoms and their perceptions regarding the curability of their illness. Also, this study assesses patient and caregiver self-reported perceptions about prognosis, but, because we did not record conversations with providers or inquire about where patients and caregivers obtained information about the illness, we do not have the ability to opine on how illness understanding may relate to information sources. Not only may patients and caregivers find information on the internet, but they also interact with many providers on their multidisciplinary team who may provide additional information about the illness and treatment goals. Moreover, although we sampled participants at 3 months after diagnosis, it is possible that some patients and caregivers had not yet engaged in prognostic discussions with their providers by this time, which is fairly early in the course of treatment. Lastly, this study assessed patients’ cognitive function only according to MMSE status. More robust neuropsychological testing to understand patients’ cognitive function could help determine whether impaired cognition mediates apparent prognostic awareness in patients.

In conclusion, the majority of patients with newly diagnosed malignant gliomas and their caregivers desire information about prognosis but report that they infrequently discuss prognosis with their oncologists. Many patients with malignant gliomas, and to a lesser degree their caregivers, report inaccurate assessments of their prognosis and primary treatment goal shortly after beginning their cancer treatment. Patients and caregivers often report a primary treatment goal that differs from their perception of the oncologist’s primary goal. In addition, there is significant discordance among patient-caregiver dyads, with patients more frequently reporting that their own goal and/or their oncologist’s goal is to cure their cancer. Our findings highlight the need for a better understanding of the source of these discrepancies and identification of the barriers to effective communication between patients with malignant gliomas, their caregivers, and their oncologists. Such understanding is necessary to inform the development of interventions to enhance communication about prognosis in this population. In addition, although patients report wanting to know as much as possible about their prognosis, patients with an accurate understanding of their prognosis have greater depressive symptoms, suggesting that this is a vulnerable population with significant supportive care needs. Further investigation is needed to identify the optimal means of promoting improved patient-caregiver-clinician communication about prognosis while adequately addressing the psychological distress associated with coping with a terminal brain cancer diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Pappas Center for Neuro-Oncology and the Cancer Outcomes Research Group at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center.

Conflict of interest statement.

Dr Forst has ownership interest in Eli Lilly. Dr Greer has received consultant fees from Concerto HealthAI, has collected royalties from Humana Press/Springer, and is the investigator for an industry-sponsored study with Gaido Health/BCG Digital Ventures. Dr Batchelor is on the scientific advisory board for Genomicare. Dr Temel has received research support from Pfizer. The remaining authors have no pertinent conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Park ER, et al. Associations among prognostic understanding, quality of life, and mood in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(2):278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Innes S, Payne S. Advanced cancer patients’ prognostic information preferences: a review. Palliat Med. 2009;23(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PA, et al. Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yennurajalingam S, Rodrigues LF, Shamieh O, et al. Perception of curability among advanced cancer patients: an international collaborative study. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):501–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3809–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al. Physicians’ propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients’ awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(6):673–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finlayson CS, Chen YT, Fu MR. The impact of patients’ awareness of disease status on treatment preferences and quality of life among patients with metastatic cancer: a systematic review from 1997-2014. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wen FH, Chen JS, Chang WC, Chou WC, Hsieh CH, Tang ST. Accurate prognostic awareness and preference states influence the concordance between terminally ill cancer patients’ states of preferred and received life-sustaining treatments in the last 6 months of life. Palliat Med. 2019;33(8):1069–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang ST, Liu TW, Chow JM, et al. Associations between accurate prognostic understanding and end-of-life care preferences and its correlates among Taiwanese terminally ill cancer patients surveyed in 2011-2012. Psychooncology. 2014;23(7):780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Coping and prognostic awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2551–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sato T, Soejima K, Fujisawa D, et al. Prognostic understanding at diagnosis and associated factors in patients with advanced lung cancer and their caregivers. Oncologist. 2018;23(10):1218–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diamond EL, Corner GW, De Rosa A, Breitbart W, Applebaum AJ. Prognostic awareness and communication of prognostic information in malignant glioma: a systematic review. J Neurooncol. 2014;119(2):227–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Applebaum AJ, Buda K, Kryza-Lacombe M, et al. Prognostic awareness and communication preferences among caregivers of patients with malignant glioma. Psychooncology. 2018;27(3):817–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamond EL, Prigerson HG, Correa DC, et al. Prognostic awareness, prognostic communication, and cognitive function in patients with malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(11):1532–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al. Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in family caregivers of patients with incurable cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1607–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6516):344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moser MT, Künzler A, Nussbeck F, Bargetzi M, Znoj HJ. Higher emotional distress in female partners of cancer patients: prevalence and patient-partner interdependencies in a 3-year cohort. Psychooncology. 2013;22(12):2693–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parker Oliver D, Washington K, Smith J, Uraizee A, Demiris G. The prevalence and risks for depression and anxiety in hospice caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(4):366–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robinson TM, Alexander SC, Hays M, et al. Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(9):1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koedoot CG, Oort FJ, de Haan RJ, Bakker PJ, de Graeff A, de Haes JC. The content and amount of information given by medical oncologists when telling patients with advanced cancer what their treatment options are. Palliative chemotherapy and watchful-waiting. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(2):225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Osch M, Sep M, van Vliet LM, van Dulmen S, Bensing JM. Reducing patients’ anxiety and uncertainty, and improving recall in bad news consultations. Health Psychol. 2014;33(11):1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a patient-centered communication intervention on oncologist-patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: the VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rodenbach RA, Brandes K, Fiscella K, et al. Promoting end-of-life discussions in advanced cancer: effects of patient coaching and question prompt lists. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):842–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: a cluster randomized clinical trial of the serious illness care program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shen MJ, Trevino KM, Prigerson HG. The interactive effect of advanced cancer patient and caregiver prognostic understanding on patients’ completion of Do Not Resuscitate orders. Psychooncology. 2018;27(7):1765–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trevino KM, Prigerson HG, Shen MJ, et al. Association between advanced cancer patient-caregiver agreement regarding prognosis and hospice enrollment. Cancer. 2019;125(18):3259–3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wright AA, Zhang B, Keating NL, Weeks JC, Prigerson HG. Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.