Introduction

Taking into account and evaluating the presence of a physical illness plays a crucial role in the clinical encounter with the elderly who may present suicidal ideation (SI) and suicidal behavior (SB) (1, 2).

On the one hand, physical illness is associated with greater suicidality risk in the elderly. This association has been inferred from both quantitative and qualitative findings based on population and registry cohorts (3–5), case-control studies (6–13), psychological autopsies (14, 15), coroners’ reports (16, 17), and suicide notes (17, 18) [for reviews, see (19, 20)]. This applies to SI/wishes to die (20–22) and the entire span of SB, including suicide attempts (SAs) and completed suicides [for reviews, see (20, 23, 24)].

On the other hand, a physical illness may render the suicidality assessment of the elderly complex for multiple reasons (25): a) the possible presence of uncommon or masking clinical features of both SB (indirect or passive SB, e.g. self-starvation) and psychiatric disorders associated with SB (e.g. atypical depressive disorders with prevalent somatic or cognitive symptoms) (26–28); b) the risk of overlooking and missing SB when severe illnesses coexist (29); c) the frequent reticence among the elderly in externalizing SI as they place more emphasis on their physical conditions (30–33); and d) the eventual caregivers’ representations of suicide as a more “understandable” act when facing greater physical fragilities and the intrinsic proximity of the end of life (34, 35). S. de Beauvoir wrote in the 1970s about the feeling of resignation or impotence of what may be considered an inexorable outcome: “Some suicides of elder people follow states of neurotic depression that one has not been able to heal; but most are normal reactions to an irreversible, desperate situation, experienced as intolerable” (36).

A large number of the elderly who died by suicide had had recent contact with primary healthcare professionals, including in emergency departments (EDs). Approximately 50 to 70% of individuals had consulted a healthcare professional in the 30 days preceding their death (32, 37), and more than 80% had done so in the six months prior to death (38). In most of these cases, the last consultation had focused on physical complaints in the absence of a psychiatric diagnosis (32, 37). Notably, affective disorders in the geriatric population can go undiagnosed by ED physicians (39).

The aim of this opinion paper is to point out the opportunity of assessing suicidality in the elderly when they present to the ED with physical illness. To this purpose, it could be useful to overview some both controversial and consensual key points on suicidality risk in the elderly, as discussed below.

Discussion

Some Controversial Matters

When considering whether the presence of the physical disease is a significant risk factor for suicidality in older versus younger patients, a legitimate objection could be that the former has statistically higher somatic susceptibility. The same objection could be raised to the argument that an the increasing rate of SI/wishes to die (21), SAs (40), and completed suicides (5, 6, 8, 41) in the elderly has been observed in the presence of multiple somatic illnesses (a “burden of physical illness”). The answer to this question is probably addressed by qualitative studies, from which the subjective attributions of mental suffering as a consequence of one or more physical illnesses have emerged (14, 15, 17, 18).

Another debated point is the extent to which mental comorbidities contribute to the suicidality risk in the elderly (1). Psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder and substance use disorder have been shown to play a significant role in death by suicide among individuals older than 65 years (6, 42, 43). While some studies found that the effect of physical illness on suicidality risk persisted even after controlling for comorbid mental disorders (5, 9), others have relegated physical illness to a secondary contributing risk factor (16, 29). Major depressive disorder, in analogy with functional impairment or pain, could be considered as a possible mediating factor that partially explains the link between physical illness and suicidality risk (physical illness causes/contributes to the occurrence of depressive disease and the latter increases suicidality risk); similarly, substance use disorder (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepine, or opioids abuse) may be included in this reciprocal link, initially interpreted as tentative of self-medication that eventually exacerbates both major depression and suicidality (4, 19, 28, 43–45).

And Some Common Clinical Features

In recent years, studies have highlighted the role of physical illness, especially among the oldest patients. Physical illness exerted a stronger motivational effect for suicide in old-old (≥75 years old) attempters compared to their young-old (65–74 years old) and middle-aged (64–50 years old) counterparts (46). One-third of those 70+ years of age who had attempted suicide attributed their act to somatic distress (47). Among those who had died by suicide, a greater incidence of physical illness was reported in the old-old compared to the young-old (38, 48) and middle-aged adults (38). Those in whom the reason for completed suicide was attributed to the presence of physical illness were older than those in whom the reason was attributed to the presence of mental illness (17). Hospitalization due to physical illness had the greatest influence on the risk of completed suicide among the old-old (41).

Contrary to findings in the general population, in the elderly non-lethal events seem to be more common in males (1), especially among the young-old where this has been attributed to so-called “elderly adolescentism” (49). Improvements to welfare and healthcare may have led to a rejuvenation of the 65–74 age group, which could be at the origin of certain behavioral patterns such as SA intended as a “cry-for-help” in response to environmental adversities (49). In this case, the stressful context could be represented by the occurrence of one or more physical illnesses (49). In studies that did not utilize the distinction between old-old, middle-aged, and young adults, the proportion reporting that SA was due to physical illness did not differ between males and females in the 70+ age group (47, 50). As far as completed suicides, the presence of physical illness should be considered as a warning sign, especially in males (15), in particular, those with serious and multiple illnesses (6). The risk of completed suicides has been shown to differ between males than females depending on the type of physical illness (4). In the old-old patients, hospitalization with a physical illness conferred a greater risk of completed suicides in males (41).

Globally, neurological diseases, pain, and oncological conditions occurred more frequently in the suicidal elderly. An association between neurologic diseases and SI, SA, and SB was observed (6, 12, 51–55), especially for stroke and hemiplegia (4, 11, 13, 56, 57), epilepsy (4, 8, 45, 58), and dementia (13, 59, 60). A greater rate of SI was documented in patients with Parkinson’s disease (60, 61), and the role of sub-thalamic deep brain stimulation (DBS) on suicidality risk in patients treated for extrapyramidal movement disorders is still discussed [for a recent systematic review, see (62)]. The pain was significantly and independently associated with SI/wishes to die (21, 22, 63–66) and completed suicides (8, 10, 17). Oncological conditions in the elderly were shown to be associated with SI, and the entire span of SB (3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 13, 17, 67, 68).

Conclusions

The elderly who attend the ED with a physical illness are vulnerable individuals and the ED visit often represents a “sentinel event” that may signal a medical or psychosocial fracture in their established equilibrium (69, 70).

In addition to investigation and management of physical illness, attention needs to be paid to its psychic repercussion on the elderly. This also includes addressing and assessing suicidality that, for the reasons synthesized in the introduction, is frequent in this population but can be missed by the clinician. In a specular way, recommendations on suicidality prevention measures in the elderly encourage a so-called “multi-faceted” approach, which emphasizes the in-depth consideration of aspects related to the presence of physical illness, considered among the most relevant determinants of the elderly’s SI and SB (37, 71–74).

This opportunity involves both primary healthcare professionals and psychiatrists. The ED represents a clinical setting where the elderly with both physical illness and greater suicidality risk frequently converge. Conversely, the ED, by offering an integrated somatic/psychiatric approach, constitutes a precious resource for this complex and fragile population.

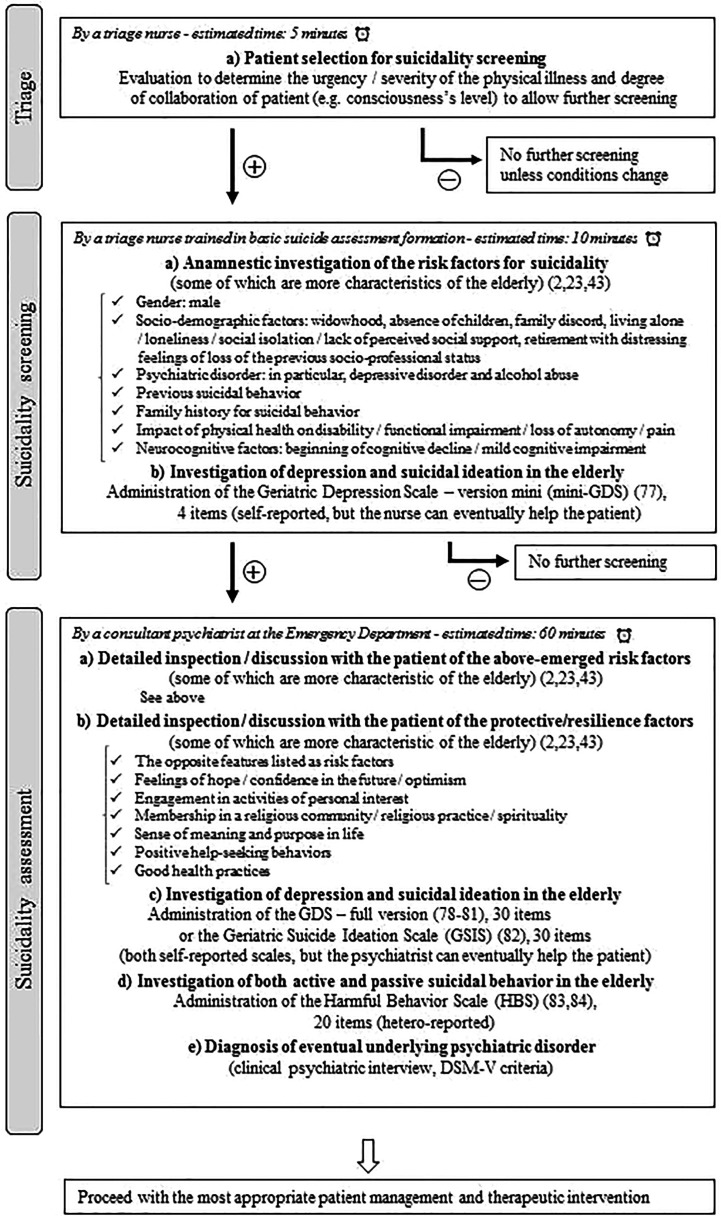

Not every elderly patient who arrives at the ED with physical illness can be screened for suicide. Thus, there are some pragmatic considerations, which would limit this approach in the clinical practice. They are dictated by the clinical condition of the patient (e.g. urgency/severity of the physical illness, consciousness’s level) and the amount of resources, regarding both staff and time, which can be allotted for the suicidality assessment. To achieve a more balanced cost-benefit ratio, we propose —mainly on the basis of a previous Canadian work (75)— a potential example of a tiered assessment (2, 23, 43, 76–83) ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

A proposal for a potential tiered suicidality assessment in the elderly with physical illness attending an Emergency Department.

The ED, the place of what cannot be deferred, may be finally at the center of the clinical and human encounter with the elderly who, confronted with the possibility of approaching the end of their existences (perceived as more concrete or urgent by the presence of physical illness), present a moral pain experienced as non-repairable. The dialogue with these patients in the ED can constitute the beginning of a therapeutic relationship aimed at trying to understand the individual meaning to the urgency of their days, and therefore to explore an alternative to suicide as unique possibility to avoid the unbearable psychache.

Future research is needed to refine the comprehension of the suicidality peculiarities in the elderly population and translate it into clinical practice through an eventual feasible, validated, and consensual screening.

Author Contributions

AC, AAm, MR, and JA researched the literature and drafted the primary manuscript. SM, MPr, AAg, and GS carefully revised the manuscript. GS, MA, GB, LM, and MPo supervised all steps of the work and provided the intellectual impetus. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1. De Leo D, Draper B, Krysinska K. Suicidal elderly people in clinical and community settings. Risk factors, treatment and suicide prevention. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; (2009). p. 703–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am (2011) 34:451–68. 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shelef A, Hiss J, Cherkashin G, Berger U, Aizenberg D, Baruch Y, et al. Psychosocial and medical aspects of older suicide completers in Israel: a 10-year survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2014) 29:846–51. 10.1002/gps.4070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Conwell Y. Physical diseases as predictors of suicide in older adults: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2015) 50:1427–39. 10.1007/s00127-015-1051-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Almeida OP, McCaul K, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. Suicide in older men: the health in men cohort study (HIMS). Prev Med (2016) 93:33–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Runeson B, Skoog I, Wilhelmson K, Allebeck P. Burden of illness and suicide in elderly people: case-control study. BMJ (2002) 324:1355. 10.1136/bmj.324.7350.1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quan H, Arboleda-Flórez J, Fick GH, Stuart HL, Love EJ. Association between physical illness and suicide among the elderly. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2002) 37:190–7. 10.1007/s001270200014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, Kopp A, Redelmeier DA. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med (2004) 164:1179–84. 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Conner KR, Eberly S, Caine ED. Suicide at 50 years of age and older: perceived physical illness, family discord and financial strain. Psychol Med (2004) 34:137–46. 10.1017/s0033291703008584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harwood DMJ, Hawton K, Hope T, Harriss L, Jacoby R. Life problems and physical illness as risk factors for suicide in older people: a descriptive and case-control study. Psychol Med (2006) 36:1265–74. 10.1017/S0033291706007872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Voaklander DC, Rowe BH, Dryden DM, Pahal J, Saar P, Kelly KD. Medical illness, medication use and suicide in seniors: a population-based case control study. J Epidemiol Commun Health (2008) 62:138–46. 10.1136/jech.2006.055533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Hirsch JK, Conner KR, Eberly S, Caine ED. Health status and suicide in the second half of life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2010) 25:371–9. 10.1002/gps.2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jia CX, Wang LL, Xu AQ, Dai AY, Qin P. Physical illness and suicide risk in rural residents of contemporary China. Crisis (2014) 35:330–7. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harwood D, Hawton K, Hope T, Jacoby R. Suicide in older people without psychiatric disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2006) 21:363–7. 10.1002/gps.1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pompili M, Innamorati M, Masotti V, Personnè F, Lester D, Di Vittorio C, et al. Suicide in the elderly: a psychological autopsy study in a North Italy area (1994–2004). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2008) 16:727–35. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318170a6e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Snowdon J, Baume P. A study of suicides of older people in Sydney. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2008) 17:261–9. 10.1002/gps.586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fegg M, Kraus S, Graw M, Bausewein C. Physical compared to mental diseases as reasons for committing suicide: a retrospective study. BMC Palliat Care (2016) 15:14. 10.1186/s12904-016-0088-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheung G, Merry S, Sundram F. Late-life suicide: insight on motives and contributors derived from suicide notes. J Affect Disord (2015) 185:17–23. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fiske A, O’Riley AA, Widoe RK. Physical health and suicide in late life: an evaluative review. Clin Gerontol (2008) 31:31–50. 10.1080/07317110801947151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fässberg MM, Cheung G, Canetto SS, Erlangsen A, Lapierre S, Lindner R, et al. A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults. Aging Ment Health (2016) 20:166–94. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1083945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lapierre S, Boyer R, Desjardins S, Dubé M, Lorrain D, Préville M, et al. Daily hassles, physical illness, and sleep problems in older adults with wishes to die. Int Psychogeriatr (2012) 24:243–52. 10.1017/S1041610211001591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lapierre S, Desjardins S, Préville M, Berbiche D, Lyson Marcoux M. Wish to die and physical illness in older adults. Psychol Res (Libertyville IL) (2015) 5:125–37. 10.17265/2159-5542/2015.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Draper B. Editorial Review. Attempted suicide in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (1996) 11:577–87. 10.1002/gps.1739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan J, Draper B, Banerjee S. Deliberate self-harm in older adults: a review of the literature from 1995 to 2004. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2007) 22:720–32. 10.1002/gps.1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Orden KA, Conwell Y. Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment Health (2016) 20:240–51. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1065791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gottfries CG. Is there a difference between elderly and younger patients with regard to the symptomatology and aetiology of depression? Int Clin Psychopharmacol (1998) 13(Suppl 5):613–8. 10.1097/00004850-199809005-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szanto K, Gildengers A, Mulsant BH, Brown G, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF. Identification of suicidal ideation and prevention of suicidal behaviour in the elderly. Drugs Aging (2002) 19:11–24. 10.2165/00002512-200219010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2009) 5:363–89. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Suominen K, Henriksson M, Isometsä E, Conwell Y, Heilä H, Lönnqvist J. Nursing home suicides—a psychological autopsy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2003) 18:1095–101. 10.1002/gps.1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Seidlitz L, Lyness JM, Cox C, Caine ED. Age and suicidal ideation in older depressed inpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (1999) 7:289–96. 10.1097/00019442-199911000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Waern M, Beskow J, Runeson B, Skoog I. Suicidal feelings in the last year of life in elderly people who commit suicide. Lancet (1999) 354:917–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)93099-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harwood DMJ, Hawton K, Hope T, Jacoby R. Suicide in older people: mode of death, demographic factors, and medical contact before death. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2000) 15:736–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Betz ME, Schwartz R, Boudreaux ED. Unexpected suicidality in an older emergency department patient. J Am Geriatr Soc (2013) 61:1044–5. 10.1111/jgs.12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Costanza A, Baertschi M, Weber K, Canuto A, Sarasin F. Le patient suicidaire âgé aux Urgences [Suicidal elderly patient at the emergency department]. La Gazette Med (2015) 4:12–3. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winterrowd E, Canetto SS, Benoit K. Permissive beliefs and attitudes about older adult suicide: a suicide enabling script? Aging Ment Health (2015) 21:173–81. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1099609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Beauvoir S. La Vieillesse [Old age]. Gallimard: Paris, France: (1970). p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR. Suicide in elders. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2001) 932:132–50. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Innamorati M, Pompili M, Di Vittorio C, Baratta S, Masotti V, Badaracco A, et al. Suicide in the old elderly: results from one Italian county. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2014) 22:1158–67. 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meldon SW, Emerman CL, Schubert DS. Recognition of depression in geriatric ED patients by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med (1997) 30:442–7. 10.1016/s0196-0644(97)70002-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levy TB, Barak Y, Sigler M, Aizenberg D. Suicide attempts and burden of physical illness among depressed elderly inpatients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2011) 52:115–7. 10.1016/j.archger.2010.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Erlangsen A, Vach W, Jeune B. The effect of hospitalization with medical illnesses on the suicide risk in the oldest old: a population-based register study. J Am Geriatr Soc (2005) 53:771–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53256.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McIntosh JL. Suicide prevention in the elderly (age 65-99). Suicide Life Threat Behav (1995) 25:180–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Conwell Y, Thompson C. Suicidal behavior in elders. Psychiatr Clin North Am (2008) 31:333–56. 10.1016/j.psc.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2003) 58:249–65. 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cheung G, Sundram F. Understanding the progression from physical illness to suicidal behavior: a case study based on a newly developed conceptual model. Clin Gerontol (2017) 40:124–9. 10.1080/07317115.2016.1217962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim H, Ahn JS, Kim H, Cha YS, Lee J, Kim MH, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of old-old suicide attempters compared with young-old and middle-aged attempters. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2018) 33:1717–26. 10.1002/gps.4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wiktorsson S, Berg AI, Wilhelmson K, Mellqvist Fässberg M, Van Orden K, Duberstein P, et al. Assessing the role of physical illness in young old and older old suicide attempters. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2016) 31:771–4. 10.1002/gps.4390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Paraschakis A, Douzenis A, Michopoulos I, Christodoulou C, Vassilopoulou K, Koutsaftis F, et al. Late onset suicide: distinction between “young-old” vs. “old-old” suicide victims. How different populations are they? Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2012) 54:136–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amore M, Solano P. Comportamento suicidario nell’anziano. In: Pompili M, Girardi P, editors. Manuale di Suicidologia. Pisa, Italy: Pacini; (2015). p. 397–416. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wiktorsson S, Rydberg Sterner T, Mellqvist Fässberg M, Skoog I, Ingeborg Berg A, Duberstein P, et al. Few sex differences in hospitalized suicide attempters aged 70 and above. Int J Env Res Public Health (2018) 15:E141. 10.3390/ijerph15010141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arciniegas DB, Anderson CA. Suicide in neurologic illness. Curr Treat Options Neurol (2002) 4:457–68. 10.1007/s11940-002-0013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coughlin SS, Sher L. Suicidal behavior and neurological Illnesses. J Depress Anxiety (2013) Suppl 9:12443. 10.4172/2167-1044.S9-001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Costanza A, Baertschi M, Weber K, Canuto A. Maladies neurologiques et suicide: de la neurobiologie au manque d’espoir [Neurological diseases and suicide: from neurobiology to hopelessness]. Rev Med Suisse (2015) 11:402–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Eliasen A, Dalhoff KP, Horwitz H. Neurological diseases and risk of suicide attempt: a case-control study. J Neurol (2018) 265:1303–9. 10.1007/s00415-018-8837-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Costanza A, Amerio A, Aguglia A, Escelsior A, Serafini G, Berardelli I, et al. When sick brain and hopelessness meet: some aspects of suicidality in the neurological patient. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets (2020). 10.2174/1871527319666200611130804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stenager EN, Madsen C, Stenager E, Boldsen J. Suicide in patients with stroke: epidemiological study. BMJ (1998) 316:1206–10. 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Teasdale TW, Engberg AW. Suicide after a stroke: a population study. J Epidemiol Community Health (2001) 55:863–6. 10.1136/jech.55.12.863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB, Sidenius P, Agerbo E. Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case–control study. Lancet Neurol (2007) 68:693–8. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70175-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Erlangsen A, Zarit SH, Conwell Y. Hospital-diagnosed dementia and suicide: a longitudinal study using prospective, nationwide register data. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2008) 16:220–8. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181602a12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Serafini G, Calcagno P, Lester D, Girardi P, Amore M, Pompili M. Suicide risk in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Curr Alzheimer Res (2016) 13:1083–99. 10.2174/1567205013666160720112608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Berardelli I, Belvisi D, Corigliano V, Costanzo M, Innamorati M, Fabbrini G, et al. Suicidal ideation, perceived disability, hopelessness and affective temperaments in patients affected by Parkinson’s disease. Int J Clin Pract (2018) 19, e13287. 10.1111/ijcp.13287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Berardelli I, Belvisi D, Nardella A, Falcone G, Lamis DA, Fabbrini G, et al. Suicide in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets (2019) 18:466–77. 10.2174/1871527318666190703093345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Awata S, Seki T, Koizumi Y, Sato S, Hozawa A, Omori K, et al. Factors associated with suicidal ideation in an elderly urban Japanese population: a community-based, cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2005) 59:327–36. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Li LW, Conwell Y. Pain and self-injury ideation in elderly men and women receiving home care. J Am Geriatr Soc (2010) 58:2160–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03151.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kang HJ, Stewart R, Jeong BO, Kim SY, Bae KY, Kim SW, et al. Suicidal ideation in elderly Korean population: a two-year longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr (2014) 26:59–67. 10.1017/S1041610213001634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jorm AF, Henderson AS, Scott R, Korten AE, Christensen H, Mackinnon AJ. Factors associated with the wish to die in elderly people. Age Ageing (1995) 24:389–92. 10.1093/ageing/24.5.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Llorente MD, Burke M, Gregory GR, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Horner RD, et al. Prostate cancer: a significant risk factor for late-life suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2005) 13:195–201. 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Miller M, Mogun H, Azrael D, Hempstead K, Solomon DH. Cancer and the risk of suicide in older Americans. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26:4720–4. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Carter MW, Reymann MR. ED use by older adults attempting suicide. Am J Emerg Med (2014) 32:535–40. 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Betz ME, Arias SA, Segal DL, Miller I, Camargo CA, Jr, Boudreaux ED. Screening for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in older adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc (2016) 64:e72–7. 10.1111/jgs.14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Erlangsen A, Nordentoft M, Conwell Y, Waern M, De Leo D, Lindner R, et al. International Research Group on Suicide among the Elderly. Key considerations for preventing suicide in older adults: consensus opinions of an expert panel. Crisis (2011) 32:106–9. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Conwell Y. Suicide later in life: challenges and priorities for prevention. Am J Prev Med (2014) 47:S244–50. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Draper BM. Suicidal behaviour and suicide prevention in later life. Maturitas (2014) 79:179–83. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Raue PJ, Ghesquiere AR Bruce ML. Suicide risk in primary care: identification and management in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep (2014) 16:466. 10.1007/s11920-014-0466-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health National guidelines for Seniors" mental health - The assessment of suicide risk and prevention of suicide (2006). Available at: https://ccsmh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/NatlGuideline_Suicide.pdf (Accessed June 10, 2020).

- 76. Hammami S, Hajem S, Barhoumi A, Koubaa N, Gaha L, Laouani Kechrid C. Screening for depression in an elderly population living at home. Interest of the Mini-Geriatric Depression Scale. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique (2012) 60:287–93. 10.1016/j.respe.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res (1982) 17:37–49. 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Heisel MJ, Flett GL, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Does the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) distinguish between older adults with high versus low levels of suicidal ideation? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2005) 13:876–83. 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Heisel MJ, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM, Feldman MD. Screening for suicide ideation among older primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Med (2010) 23:260–9. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.080163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cheng ST, Edwin CS, Lee SY, Wong JY, Lau KH, Chan LK, et al. The Geriatric Depression Scale as a screening tool for depression and suicide ideation: a replication and extention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2010) 18:256–65. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bf9edd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Heisel MJ, Flett GL. The development and initial validation of the Geriatric Suicide Ideation Scale. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2006) 14:742–51. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000218699.27899.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Draper B, Brodaty H, Low LF, Richards V, Paton H, Lie D. Self-destructive behaviors in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc (2002) 50:354–8. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Draper B, Brodaty H, Low LF, Richards V. Prediction of mortality in nursing home residents: impact of passive self-harm behaviors. Int Psychogeriatr (2003) 15:187–96. 10.1017/s1041610203008871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]