Abstract

Primary gastric mucormycosis is a rare but potentially lethal fungal infection due to the invasion of Mucorales into the gastric mucosa. It may result in high mortality due to increased risk of complications in immunocompromised patients. Common predisposing risk factors to develop gastric mucormycosis are prolonged uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with or without diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), solid organ or stem cell transplantation, underlying hematologic malignancy, and major trauma. Abdominal pain, hematemesis, and melena are common presenting symptoms. The diagnosis of gastric mucormycosis can be overlooked due to the rarity of the disease. A high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis and management of the disease, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Radiological imaging findings are nonspecific to establish the diagnosis, and gastric biopsy is essential for histological confirmation of mucormycosis. Prompt treatment with antifungal therapy is the mainstay of treatment with surgical resection reserved in cases of extensive disease burden or clinical deterioration. We presented a case of acute gastric mucormycosis involving the body of stomach in a patient with poorly controlled diabetes and chronic renal disease, admitted with acute onset of abdominal pain. Complete resolution of lesion was noted with 16 weeks of medical treatment with intravenous amphotericin B and posaconazole.

1. Introduction

Gastric mucormycosis is a rare but lethal fungal infection due to invasion of Mucorales (a filamentous fungus) into the gastric mucosa that may result in high mortality (up to 54%) in immunocompromised patients [1]. An estimated 75% of mucormycosis (formally known as zygomycosis) infection is caused by the fungi class of zygomycetes and particularly Mucor, Rhizopus, or Rhizomucor species [1–3]. Common sites of mucormycosis are upper respiratory tract, nasal or paranasal sinuses, skin, orbit, and brain; however, the gastrointestinal tract is rarely infected [4]. Serologic biomarkers are nonspecific; however, a biopsy from the affected site is the gold standard to establish histologic diagnosis of mucormycosis. A positive culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on biopsy specimen is occasionally required for diagnosis confirmation. Medical management with antifungal therapy such as lipid formulation of amphotericin B, posaconazole, and newer agents isavuconazole or triazole is the mainstay option for treating gastric mucormycosis [5, 6]. For patients with severe disease such as tissue necrosis and those with late presentation, a combination of both medical management with early surgical resection may improve the outcome of disease. We present a case of an immunocompetent individual who developed gastric mucormycosis.

2. Case Presentation

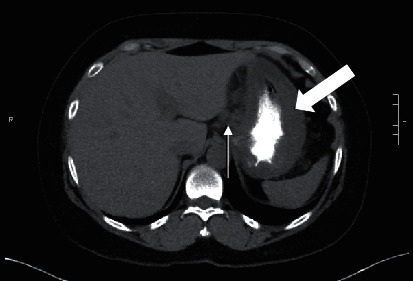

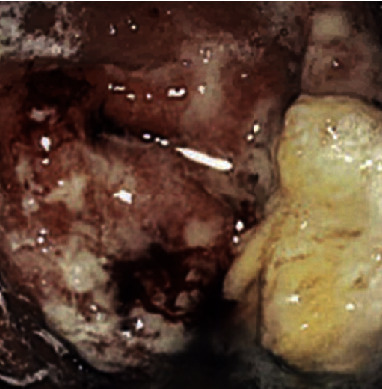

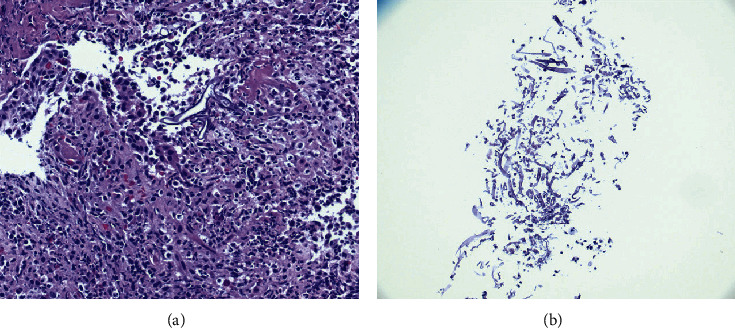

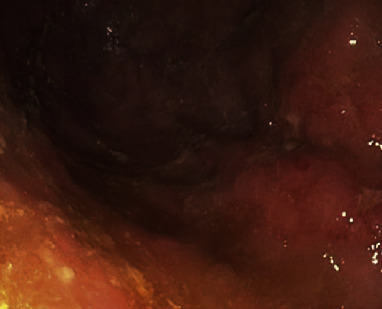

A 55-year-old female with past medical history of insulin-dependent uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and stage IIIb chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency room with acute abdominal pain for two weeks. The abdominal pain was epigastric, 7/10 in severity, and nonradiating, without precipitating or relieving factors. It was associated with nausea and multiple episodes of nonbiliary, nonbloody emesis. On physical examination, vitals were unremarkable. Epigastric tenderness was noted on abdominal examination. Laboratory workup was remarkable for leukocytosis (11.2 k/ul), elevated lipase (589 u/L), and elevated creatinine (1.62 mg/dL). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1) demonstrated transmural thickening at gastric body and fundus, with associated perigastric inflammation and reactive adenopathy. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed multiple ulcerated sessile masses in the gastric fundus with a large exudate covering mass (Figure 2). Biopsy of mass revealed polymorphonuclear neutrophils indicating inflammation of gastric mucosa and fragments of invasive fungal hyphae (zygomycetes) with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture of the biopsy specimens detecting Rhizopus microsporus DNA (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). The patient was not amenable to the surgical resection because of multiple comorbidities and high risk for surgical complications. She was medically treated with intravenous amphotericin B 5 mg/kg daily that was later switched to posaconazole 300 mg daily due to worsening renal function and poor tolerance. Surveillance of the gastric lesions was performed with serial EGDs. Complete resolution of gastric mucormycosis with the absence of hyphae was noted on endoscopic gastric biopsies after 16 weeks of antifungal therapy (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

CT scan of the abdomen displaying the transmural thickening of the stomach (white blocked arrow) and the perigastric inflammation with reactive adenopathy (white arrow).

Figure 2.

Upper endoscopy showing ulcerated lesion in the gastric fundus with the overlaying bleeding and exudative material.

Figure 3.

Histological examination of lesion showing polymorphonuclear neutrophils indicating inflammation of gastric mucosa (a) and fragments of invading fungal hyphae (b).

Figure 4.

Repeat EGD showing cleared infection and ulceration in the fundus of the stomach.

3. Discussion

An estimated prevalence of mucormycosis is 0.16 (0.12 to 0.20) per 10,000 patients [7]. The prevalence rate of mucormycosis amongst patients with uncontrolled diabetes is 36% [8]. We presented a case of acute gastric mucormycosis in a patient with poorly controlled diabetes and chronic renal disease, admitted with acute onset of abdominal pain. An uncontrolled diabetes and CKD stage IIIb were major risk factors predisposing to the development of gastric mucormycosis. The patient's symptoms were not amenable to proton pump inhibitors which prompted further investigation including abdominal radiological imaging and upper endoscopy. Radiological imaging findings were nonspecific; however, EGD revealed multiple ulcerated sessile masses located at greater curvature and gastric fundus. These mucosal lesions were covered with a large grayish exudate, highly suspicious for gastric mucormycosis. The diagnosis of gastric mucormycosis was confirmed with histological examination, culture, and PCR of biopsy specimen.

Gastrointestinal mucosal involvement could be the sole manifestations of mucormycosis that accounts for approximately 7% of all reported cases [1]. Among gastrointestinal mucormycosis, the stomach is the most commonly affected organ (67%), followed by the colon (21%), small intestine (4%), and esophagus (2%) [1, 4, 8, 9]. The invasion of Mucorales into the body occurs through inhalation, ingestion, or inoculation of the spores [8]. The ingestion of the spores possibly from being present in fermented milk, dried bread products, fermented porridges, and alcoholic beverages derived from infected corn is the primary mode of Mucorales entry into the gastrointestinal tract. And even possibly from infected tongue depressors at physician clinics [2]. An iatrogenic gastric mucormycosis has been reported in a study from using a wooden tongue depressor and wooden applicators for crushing and mixing medication for a critically ill patient on tube feeding [10]. While immunocompetent hosts can fight off the invasion of Mucorales after ingestion of the spores into the alimentary tract, immunocompromised individuals are not able to resist mucosal invasion due to poor defence mechanism and are prone to develop severe infection. The pathogenesis of infection in diabetic patients with or without diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) remains to be elusive at this time. The proposed mechanism of gastric mucormycosis infection is the phagocytic dysfunction, impaired chemotaxis, and defective intracellular destruction of Mucorales in the presence of acidic environment of the stomach [11]. Uncontrolled diabetes and CKD may produce slightly acidic environment in the body similar to a diabetic ketoacidosis and predispose patients to mucormycosis.

In the current literature, multiple case reports on gastric mucormycosis have shown abdominal pain as the most common presenting symptom followed by hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, and odynophagia (Table 1) [4, 9, 12–44]. The predisposing risk factors to develop gastric mucormycosis are prolonged uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with or without diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), solid organ or stem cell transplantation, underlying hematologic malignancy, major trauma, utility of steroids, disseminated chronic infections, iron overload states, and severe neutropenia (Table 1) [4, 9, 12–44]. The gastric body is the most commonly affected location of gastric mucormycosis. The invasion of blood vessels under the mucosal surface may result in life-threatening gastrointestinal hemorrhage and is a poor prognostic factor of disease [4].

Table 1.

Clinical presentation and management of gastric mucormycosis.

| Study | Year | Age | Gender | Presenting symptoms | Predisposing factor | Location | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma [12] | 2020 | 66 | F | Abdominal pain | N/A | Body | Total gastrectomy and amphotericin B | Alive |

| Madireddy [13] | 2020 | 28 | M | Melena | Diabetes mellitus | Fundus | Gastrectomy, amphotericin B, and posacanozole | Alive |

| Buckholz and Kaplan [14] | 2020 | 63 | M | Epigastric pain | Hematological malignancy | Body and fundus | Total gastrectomy and amphotericin B | Died |

| Platt et al. [15] | 2019 | 33 | F | Epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting | Immunosuppressive medication | Cardia | Amphotericin B and surgical debridement | Died |

| Yusuf et al. [16] | 2019 | 51 | M | Hematemesis | Hematological malignancy | Cardia | Amphotericin B | N/A |

| Adhikari et al. [17] | 2019 | 57 | F | Hematemesis | N/A | N/A | Amphotericin B and posacanozole | Alive |

| Uchida et al. [4] | 2019 | 82 | F | Epigastric pain and melena | Immunosuppressive medication | Upper body and fundus | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Guddati et al. [18] | 2019 | 42 | M | Hematemesis | N/A | Multiple sites | Total gastrectomy | Alive |

| Sehmbey et al. [19] | 2019 | 48 | M | Coffee ground emesis | Trauma | Body and fundus | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Alfano et al. [20] | 2018 | 42 | F | Abdominal pain and melena | Organ transplantation | Posterior wall | Amphotericin B and posacanozole | Alive |

| Termos et al. [9] | 2018 | 52 | F | Abdominal pain | Diabetes | N/A | Amphotericin B and total gastrectomy | Died |

| Abreu et al. [50] | 2018 | 23 | F | Diffuse abdominal pain and vomiting | N/A | N/A | Total gastrectomy and amphotericin B | Alive |

| Gani et al. [21] | 2018 | 79 | M | Dysphagia and odynophagia | Organ transplantation | N/A | Isavuconazole | Alive |

| Sánchez-Velázquez et al. [22] | 2017 | 53 | F | Hematemesis | N/A | Cardia | Total gastrectomy | Died |

| Kgomo et al. [23] | 2017 | 38 | F | Hematemesis | HIV | Entire stomach | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Chow et al. [24] | 2017 | 34 | M | Abdominal pain and fever | Trauma | Fundus and cardia | Subtotal gastrectomy | Died |

| Nasa et al. [25] | 2017 | 31 | M | Abdominal distention | N/A | N/A | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Lee and Lee [26] | 2016 | 41 | F | Melena | Trauma | N/A | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Kim et al. [27] | 2016 | 45 | M | Weakness | Diabetic ketoacidosis | Entire stomach | Amphotericin B and gastrectomy | Alive |

| El Hachem et al. [28] | 2016 | 67 | M | Dysphagia and epigastric pain | N/A | Greater curvature | Amphotericin B and posacanozole | Alive |

| Sethi et al. [29] | 2016 | 58 | M | Hematemesis | Organ transplantation | Antrum and distal body | Amphotericin B | Alive |

| Putrus et al. [30] | 2015 | 65 | M | Abdominal pain | Diabetes mellitus | Cardia and body | Amphotericin B and total gastrectomy | Died |

| Alvarado-Lezama et al. [31] | 2015 | 32 | M | Abdominal pain | Diabetic ketoacidosis | N/A | Total gastrectomy | Died |

| Raviraj et al. [32] | 2015 | 19 | F | Fever, vomiting, and diarrhea | N/A | N/A | Amphotericin B and posacanozole | Alive |

| Kulkarni and Thakur [33] | 2014 | 50 | M | Abdominal pain and distention | Diabetes | Gastric body | Surgical intervention | Died |

| Lee et al. [34] | 2014 | 55 | M | Severe abdominal pain | N/A | N/A | Subtotal gastrectomy and amphotericin B | Alive |

| Katta et al. [35] | 2013 | 60 | M | Unconsciousness | N/A | Cardia and fundus | Amphotericin B and posacanozole | Alive |

| Dutta et al. [36] | 2012 | 64 | F | Abdominal distention and odynophagia | N/A | Fundus and body | Amphotericin B | Alive |

| Chhaya et al. [37] | 2011 | 53 | F | Melena | N/A | Body | Amphotericin B | Alive |

| Berne et al. [38] | 2009 | 55 | M | Postoperative fever | N/A | Greater curvature | Total gastrectomy and amphotericin B | Died |

| Prasad and Nataraj [39] | 2008 | 28 | M | Abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, and fever | N/A | Lesser curvature | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Ho et al. [40] | 2007 | 58 | W | Hematemesis | N/A | Posterior wall | Amphotericin B | Alive |

| Paulo De Oliveria and Milech [41] | 2002 | 17 | F | Epigastric pain | Diabetic ketoacidosis | Greater curvature and posterior wall | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Sheu et al. [42] | 1998 | 70 | M | Fever, epigastric pain, and melena | Organ transplantation | Greater curvature | Amphotericin B | Died |

| Winkler et al. [43] | 1996 | 37 | F | Melena | Organ transplantation | N/A | Amphotericin B | Alive |

| Sasaki et al. [44] | 1993 | 80 | F | Pancytopenia | Hematological malignancy | N/A | N/A | Died |

The radiological modalities such as CT scan or MRI of the abdomen usually reveal nonspecific findings such as mucosal wall thickening, mass, and reactive lymphadenopathy and prompts additional investigation with endoscopic or surgical biopsy of the lesions. EGD finding of ulcerated patchy mucosal lesions with overlying greenish or greyish exudate is a characteristic feature of gastric mucormycosis; however, biopsy of lesions is essential to differentiate it from gastric malignancy [4, 8, 21]. EGD alone does not help to make a definitive diagnosis, and additional testing with biopsy specimens is required. Histopathological and culture testing is the most definite in establishing the diagnosis. Direct microscopy, using optical brighteners, and hematoxylin and eosin stains have shown rapid visualization of the morphological structure of fungi for diagnosis of mucormycosis [45]. In addition, neutrophilic infiltration can also be seen on histological examination. PCR and fungal cultures of the specimen are occasionally needed for absolute confirmation of diagnosis. The cultures are performed on the Sabouraud agar, and rapid growth of fungi can be seen within three to seven days. Molecular-based assays, such as PCR, have shown sensitivity and specificity closer to 100% in comparison to microscopic and histopathological assays and have been noted to yield faster test results [45].

Early initiation of antifungal therapy within 6 days was found to have better patient outcomes and lower mortality rates [9, 46]. Multiple studies have shown the medical management with antifungal therapy is the mainstay treatment; however, a combination of antifungal with surgical management with either debridement or gastrectomy of mucormycosis lesions may be required in a significant number of cases specifically in those with severe disease and multiple comorbidities (Table 1) [4, 9, 12–44]. In vitro studies have shown the resistance of Mucorales to many antifungal medications such as fluconazole, ketoconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole, flucytosine, and echinocandins [47]. Commonly used antifungal medications are lipid formulation of amphotericin B (45% to 52%) and posaconazole (45%) in hospitalized patients with mucormycosis [7]. The dosage of amphotericin B remained under debate for a long time, and decision to use low versus high dose should be based upon individual patient factors including drug tolerability, side effects, and disease response to medical therapy. Currently, a dose of 5 mg/kg body is recommended by majority of physicians with a gradual escalation of dose up to 10 mg/kg for effective control of disease [45, 48, 49]. Among patients with poor tolerability of amphotericin B and those with the risk of potential side effects such as nephrotoxicity, an alternative antifungal, posaconazole, is recommended. Posaconazole is an oral agent which can also be used as maintenance agent and for long-term prophylaxis in the management of gastric mucormycosis. Although it is better tolerated than amphotericin B, in patients with hematological malignancy and gastric mucormycosis, erratic absorption of drug is concerning which may result in breakthrough infection due to suboptimal concentration of serum posaconazole. In our case, the patient was initially started on first-line antifungal agent liposomal amphotericin B. It was stopped in two weeks due to development of worsening renal function and poor tolerability. It was switched with posaconazole 300 mg daily that was also used as maintenance and salvage therapy. Posaconazole was continued for roughly four months thereafter when repeat EGD showed complete resolution of gastric mucormycosis. The duration of antifungal therapy at this time appears to be controversial given insufficient data. Serial EGD surveillance of gastric lesions is required to determine the effect of the therapy. Newer antifungal agents isavuconazole and triazole are also being utilized; however, their efficacy in resolution of the disease is still under investigation.

At times, management is not only sufficient with antifungal therapy alone and certain patients require surgical intervention. A combination of antifungal and surgical resection of lesions is indicated in case of extensive disease, angioinvasion, mucosal necrosis, and those with failed medical therapy [26, 45]. Aggressive surgical resection of necrotic lesions and negative tissue margins of fungal invasion may prevent dissemination of disease and its complications such as bowel perforation, peritonitis, and massive hemorrhage [2].

4. Conclusion

Mucormycosis is a fatal opportunistic fungal infection which may result in high mortality in untreated patients. A high index of suspicion and awareness of physicians is required for early diagnosis and management of disease particularly in immunocompromised patients. A typical presentation such as worsening abdominal pain should be investigated with CT scan or MRI and EGD in those with inconclusive finding on radiological imaging. Biopsy of the suspected mucosal lesions is the diagnostic of gastric mucormycosis. Immediate medical management with antifungal agents such as liposomal amphotericin B or posaconazole is required given the invasive nature of disease and high mortality. Serial EGD may be essential to monitor healing of gastric mucormycosis and determine duration of medical management. A combination of medical and surgical resection of mucosal lesions is warranted in the case of poor response to antifungal therapy and those with extensive disease burden.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Haider A. Naqvi and Muhammad Nadeem Yousaf were responsible for manuscript writing, figures, and review of data. Fizah S. Chaudhary contributed to data review and proofreading. Lawrence Mills was responsible for the overall supervision of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Roden M. M., Zaoutis T. E., Buchanan W. L., et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(5):634–653. doi: 10.1086/432579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrikkos G., Skiada A., Lortholary O., Roilides E., Walsh T. J., Kontoyiannis D. P. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012;54(1):S23–S34. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neofytos D., Horn D., Anaissie E., et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of multicenter prospective antifungal therapy (PATH) alliance registry. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(3):265–273. doi: 10.1086/595846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida T., Okamoto M., Fujikawa K. Gastric mucormycosis complicated by a gastropleural fistula: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98 doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018142.e18142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marty F. M., Ostrosky-Zeichner L., Cornely O. A., et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(7):828–837. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kontoyiannis D. P., Lewis R. E. How I treat mucormycosis. Blood. 2011;118(5):1216–1224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-316430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kontoyiannis D. P., Yang H., Song J. Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016;16:p. 730. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2023-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vera A., Hubscher S. G., McMaster P., Buckels J. A. C. Invasive gastrointestinal zygomycosis in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2002;73(1):145–147. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201150-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Termos S., Othman F., Alali M., et al. Total gastric necrosis due to mucormycosis: a rare case of gastric perforation. American Journal of Case Reports. 2018;19:527–533. doi: 10.12659/ajcr.908952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maraví-Poma E., Rodríguez-Tudela J. L., de Jalón J. G., et al. Outbreak of gastric mucormycosis associated with the use of wooden tongue depressors in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2004;30(4):724–728. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibrahim A. S., Kontoyiannis D. P. Update on mucormycosis pathogenesis. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2013;26(6):508–515. doi: 10.1097/qco.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma D. Successful management of emphysematous gastritis with invasive gastric mucormycosis. BMJ Case Report. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madireddy N. P. R., Uppin S. G., Uppin M. S. A rare case of gastric zygomycosis mimicking malignancy: case report with review of literature. Journal of Bacteriology and Mycology. 2020;7:p. 1126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckholz A., Kaplan A. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis presenting as emphysematous gastritis after stem cell transplant for myeloma. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2020;95(1):33–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Platt J. M., Chu J. N., Yarze J. C. Gastric mucormycosis and pneumatosis in a patient with APECED: 2717. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2019;114 doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000600400.04882.f9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yusuf A., Castellani L., Xiong X., Muller M., May G. A165 invasive gastric mucormycosis-case report of a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. 2019;2(2):326–327. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwz006.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adhikari S., Gautam A. R., Paudyal B., Sigdel K. R., Basnyat B. Case report: gastric Mucormycosis-a rare but important differential diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in an area of Helicobacter pylori endemicity. Wellcome Open Research. 2019;4:p. 5. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15026.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guddati H., Andrade C., Muscarella P., Hertan H. An unusual cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding-gastric mucormycosis. Oxford Medical Case Reports. 2019;2019(2):p. 135. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omy135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sehmbey G., Malik R., Kosa D. Gastric ulcer and perforation due to mucormycosis in an immunocompetent patient. ACG Case Reports Journal. 2019;6 doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000154.e00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alfano G., Fontana F., Francesca D., et al. Gastric mucormycosis in a liver and kidney transplant recipient: case report and concise review of literature. Transplantation Proceedings. 2018;50(3):905–909. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gani I., Doroodchi A., Falkenstrom K. Gastric mucormycosis in a renal transplant patient treated with isavuconazole monotherapy. Case Reports in Transplantation. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/9839780.9839780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez Velázquez P., Pera M., Gimeno J. Mucormycosis: an unusual cause of gastric perforation and severe bleeding in immunocompetent patients. Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas. 2017;109:223–225. doi: 10.17235/reed.2016.4269/2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kgomo M. K., Elnagar A. A., Mashoshoe K., Thomas P., Hougenhouck-Tulleken W. G. V. Gastric mucormycosis: a case report. World Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;8(1):1–3. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v8.i1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow K. L., McElmeel D. P., Brown H. G., Tabriz M. S., Omi E. C. Invasive gastric mucormycosis: a case report of a deadly complication in an immunocompromised patient after penetrating trauma. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2017;40:90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasa M., Sharma Z., Lipi L., Sud R. Gastric angioinvasive mucormycosis in immunocompetent adult, a rare occurrence. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2017;65(12):103–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S. W., Lee H. S. Gastric mucormycosis followed by traumatic cardiac rupture in an immunocompetent patient. The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016;68(2):99–103. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2016.68.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J. H., Lee H. J., Ha J. H., et al. A case of gastric mucormycosis induced necrotic gastric ulcer in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. The Korean Journal of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research. 2016;16(4):230–234. doi: 10.7704/kjhugr.2016.16.4.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El Hachem G., Chamseddine N., Saidy G. Bone marrow necrosis: an unusual initial presentation of sickle cell anemia. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia. 2016;16(1):S195–S198. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sethi S. S. N., Sandhu J. S., Kaur S., Makkar V., Sohal P. M. Gastric mucormycosis: an unusual transplant infection. International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health. 2017;6:819–821. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2017.1163623112016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putrus A. A.-G. A., AlSamman M. A., Castro-Borobio M., Khan M. B., Ng S. C. Gastric mucormycosis: a devastating fungal infection in an immunocompromised patient. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:p. S321. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(15)31061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarado-Lezama J., Espinosa-González O., García-Cano E., Sánchez-Córdova G. Gastritis enfisematosa secundaria a mucormicosis gástrica. Cirugía Y Cirujanos. 2015;83(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raviraj K. S., Miglani P., Garg A., Agarwal P. K. Gastric mucormycosis with hemolytic uremic syndrome. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2015;63(10):75–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kulkarni R. V., Thakur S. S. Invasive gastric mucormycosis-a case report. Indian Journal of Surgery. 2015;77(S1):87–89. doi: 10.1007/s12262-014-1164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S. H., Son Y. G., Sohn S. S., Ryu S. W. Successful treatment of invasive gastric mucormycosis in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a case report. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2014;8(2):401–404. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katta J., Gompf S. G., Narach T., et al. Gastric mucormycosis managed with combination antifungal therapy and no surgical debridement. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. 2013;21(4):265–268. doi: 10.1097/ipc.0b013e31826e81b3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta A., Roy M., Singh T. D. Gastric mucormycosis in an immunocompetent patient. Journal of Medical Society. 2012;26:192–194. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chhaya V., Gupta S., Arnaout A. Mucormycosis causing giant gastric ulcers. Endoscopy. 2011;43(S 02):E289–E290. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berne J. D., Villarreal D. H., McGovern T. M., Rowe S. A., Moore F. O., Norwood S. H. A fatal case of posttraumatic gastric mucormycosis. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 2009;66(3):933–935. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000233673.30138.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad B. S. S. A., Nataraj K. S. Primary gastrointestinal mucormycosis in an immunocompetent person. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2008;54:211–213. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.41805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho Y.-H., Wu B.-G., Chen Y.-Z., Wang L.-S. Gastric mucormycosis in an alcoholic with review of the literature. Tzu Chi Medical Journal. 2007;19(3):169–172. doi: 10.1016/s1016-3190(10)60011-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paulo De Oliveira J. E., Milech A. A fatal case of gastric mucormycosis and diabetic ketoacidosis. Endocrine Practice. 2002;8:44–46. doi: 10.4158/EP.8.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheu B. S., Lee P. C., Yang H. B. A giant gastric ulcer caused by mucormycosis infection in a patient with renal transplantation. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S60–S61. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler S., Susani S., Willinger B., et al. Gastric mucormycosis due to Rhizopus oryzae in a renal transplant recipient. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1996;34(10):2585–2587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2585-2587.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki A., Tsukaguchi M., Takayasu K. Myelodysplastic syndrome developing acute myelocytic leukemia with gastric mucormycosis. Rinsho Byori. 1993;41:1054–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skiada A., Lass-Floerl C., Klimko N. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis. Medical Mycology. 2018;56:93–101. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chamilos G., Lewis R. E., Kontoyiannis D. P. Delaying amphotericin B-based frontline therapy significantly increases mortality among patients with hematologic malignancy who have zygomycosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47(4):503–509. doi: 10.1086/590004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almyroudis N. G., Sutton D. A., Fothergill A. W., Rinaldi M. G., Kusne S. In vitro susceptibilities of 217 clinical isolates of zygomycetes to conventional and new antifungal agents. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2007;51(7):2587–2590. doi: 10.1128/aac.00452-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tissot F., Agrawal S., Pagano L., et al. ECIL-6 guidelines for the treatment of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis and mucormycosis in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients. Haematologica. 2017;102(3):433–444. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cornely O. A., Cuenca-Estrella M., Meis J. F., Ullmann A. J. European society of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases (ESCMID) fungal infection study group (EFISG) and European confederation of medical mycology (ECMM) 2013 joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of rare and emerging fungal diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2014;20(3):1–4. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abreu B. F. B. B. D., Duarte M. L., Santos L. R. D., Sementilli A., Figueiras F. N. A rare case of gastric mucormycosis in an immunocompetent patient. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2018;51(3):401–402. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0304-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]