Abstract

Alcohol-mediated carbonyl addition has enabled catalytic enantioselective syntheses of diverse fluorine-containing compounds without the need for stoichiometric metals or discrete redox manipulations. Reactions of this type may be separated into two broad categories: redox-neutral hydrogen auto-transfer reactions wherein lower alcohols and n-unsaturated pronucleophiles are converted to higher alcohols and corresponding 2-propanol mediated carbonyl reductive couplings.

Keywords: fluorine, iridium, ruthenium, enantioselective catalysis, carbonyl addition, hydrogen transfer

Graphical Abstract

I. Introduction

Due to the favorable biological properties of organofluorine compounds, fluorinated structural motifs appear ubiquitously across commercial pharmaceutical and agrochemical ingredients1 and many powerful methods that now exist for their synthesis.2 In the course of our ongoing exploration into transfer hydrogenative carbonyl addition,3 we have developed a suite of catalytic enantioselective methods for the formation of chiral organofluorine compounds wherein π-unsaturated reactants are converted to transient organometallic nucleophiles via alcohol-mediated hydrogen-transfer. Two reactions types have emerged: hydrogen auto-transfer processes, wherein primary alcohols serve both as reductant and carbonyl proelectrophile (enabling conversion of lower alcohols to higher alcohols), and related 2-propanol-mediated reductive couplings of discrete carbonyl reactants. Such transfer hydrogenative carbonyl additions may be differentiated from “borrowing hydrogen” processes, which promote formal alcohol substitution.4 Most importantly, unlike many classical carbonyl additions, the present alcohol-mediated processes circumvent the use of stoichiometric organometallic reagents, which pose issues of safety, require multistep syntheses, generate stoichiometric quantities of metallic byproducts and are non-cryogenic. In this account, we provide a comprehensive survey of catalytic enantioselective methods for the synthesis of chiral organofluorine compounds via alcohol-mediated carbonyl addition with an emphasis on preparative capabilities (Scheme 1). For detailed discussions of reaction mechanism and stereochemical models, the reader is referred to the primary literature citations.

Scheme 1.

Organofluorine compounds via enantioselective alcohol-mediated carbonyl addition.

II. Chiral Organofluorine Compounds via Alcohol-Mediated Carbonyl Addition

In 2008, cyclometallated π-allyliridium C,O-benzoate complexes bound by chiral chelating phosphines were shown to catalyze highly enantioselective alcohol-mediated carbonyl allylations5 and crotylations6 using allyl acetate and α-methyl allyl acetate, respectively, as pronucleophiles. In 2011, using the cyclometallated π-allyliridium C,O-benzoate complex modified by (R)-Cl,MeO-BIPHEP, related carbonyl (α-trifluoromethyl)allylations using a-trifluoromethyl allyl benzoate as pronucleophile were developed (Scheme 2).7 In reactions conducted from the alcohol oxidation level, moderate to good yields of the CF3-bearing homoallylic alcohols were generated with excellent levels of anti-diastereo- and enantioselectivity. Using 2-propanol as terminal reductant under otherwise equivalent conditions, an identical set of adducts is accessible from the aldehyde oxidation level with comparable levels of anti-diastereo- and enantioselectivity. Finally, in carbonyl (α-trifluoromethyl)allylations of enantiomerically enriched chiral γ-stereogenic alcohols, high levels of catalyst-directed stereoinduction are observed (eq. 1).

Scheme 2.

anti-Diastereo- and enantioselective iridium-catalyzed carbonyl (α-trifluoromethyl)allylation.

|

(eq. 1) |

To illustrate the utility of the reaction products, the compound obtained upon (α-trifluoromethyl)allylation of 1,4-aminobutanol was transformed to two useful N-containing building blocks (Scheme 3). Specifically, exposure to ozone followed by NaBH4 furnished a 1,3-diol, which was converted to the indicated p-toluenesulfonate in a site-selective fashion. Conversion of the p-toluenesulfonate to the CF3-bearing piperidine was then accomplished in accordance with a related literature procedure.8,9 Alternatively, the p-toluenesulfonate can be eliminated and the resulting olefin can be subjected to diastereoselective ruthenium-catalyzed hydrogenation to provide the syn-trifluoro-isopropyl-substituted secondary alcohol as a single diastereomer.10

Scheme 3.

CF3-Bearing building blocks obtained via (α-trifluoromethyl)allylation of aminobutanol.

The cyclometallated n-allyliridium C,O-benzoate complex modified by (R)-Cl,MeO-BIPHEP was also effective in promoting highly enantioselective carbonyl (2-fluoro)allylations (Scheme 4).11 Using commercially available (2-fluoro)allyl chloride as pronucleophile, benzylic, allylic and aliphatic alcohols were converted to the corresponding homoallylic alcohols in good to excellent yield with uniformly high levels of enantioselectivity. Using 2-propanol as terminal reductant under otherwise identical conditions, corresponding aldehyde reductive couplings of (2-fluoro)allyl chloride occur with roughly equivalent levels of enantioselectivity (not shown). In all cases, small quantities of defluorinated side products were observed (3–10% yield), which were easily removed upon chromatographic isolation of the product. Diastereoselective hydrogenation of the vinyl fluoride-containing products was readily achieved at ambient pressures of hydrogen gas using the Crabtree catalyst.12 In this way, syn-3-fluoro-1-alcohols are formed from primary alcohols in the absence of stoichiometric organic or metallic byproducts.

Scheme 4.

Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed carbonyl (2-fluoro)allylation.

Commercially available solutions of fluoral hydrate or difluoroacetaldehyde ethyl hemiacetal, 75 wt% in water or 90 wt% in ethanol, respectively, can be utilized in highly anti-diastereo- and enantioselective carbonyl (α-aryl)allylations (Scheme 5).13 Again, the chromatographically purified cyclometallated π-allyliridium C,O-benzoate complex modified by (S)-Cl,MeO-BIPHEP was identified as the catalyst of choice. Using 2-propanol as terminal reductant and molecular sieves to remove water and ethanol, (α-aryl)allylation of both fluoral and difluoroacetaldehyde occur in good to excellent yield with high levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity. These results are significant as nearly all enantioselective metal catalyzed additions to fluoral require anhydrous conditions involving in situ generation of gaseous fluoral, which is acutely toxic. The hydrate and hemiacetal solutions are less hazardous than their gaseous counterparts. Additionally, there is surprising paucity of catalytic enantioselective methods for formation of CHF2-bearing stereocenters.14 The ability to engage fluoral hydrate and difluoroacetaldehyde ethyl hemiacetate in highly anti-diastereo- and enantioselective (α-aryl)allylation enabled concise routes to di- and trifluoromethylated derivatives of the FDA-approved alkaloid d-hyoscyamine (dextro-atropine) (Scheme 6).15

Scheme 5.

anti-Diastereo- and enantioselective iridium-catalyzed carbonyl (α-aryl)allylation of fluoral hydrate and difluoroacetaldehyde ethyl hemiacetal.

Scheme 6.

Syntheses of CF3- and CHF2-bearing derivatives of d-hyoscyamine (dextro-atropine).

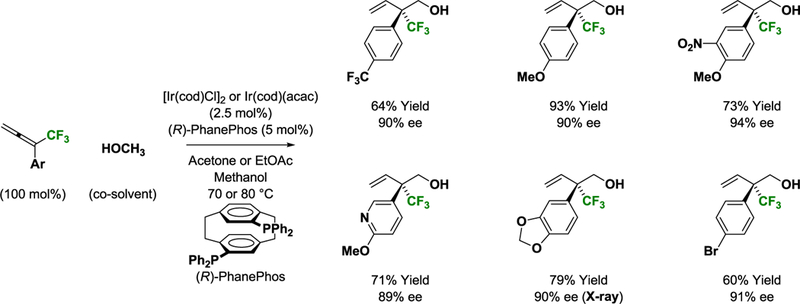

The use of methanol as a feedstock in metal catalyzed C-C coupling is an important objective in chemical synthesis.16 Following the development of non-asymmetric allene-methanol C-C couplings,17 it was found that iridium complexes modified by PhanePhos catalyze the enantioselective reductive coupling of CF3-allenes with methanol via hydrogen auto-transfer.18,19 Products of hydrohydroxymethylation are formed exclusively as the branched regioisomers with excellent levels of enantiomeric enrichment (Scheme 7). In this process, methanol dehydrogenation provides formaldehyde and an iridium hydride. Allene hydrometalation then delivers an allyliridium species that undergoes formaldehyde addition to furnish a homoallylic iridium alkoxide. Alkoxide exchange with another equivalent of methanol releases the product and closes the catalytic cycle. This transformation enables catalytic enantioselective formation of acyclic CF3-bearing quaternary carbon stereocenters without stoichiometric metals or byproducts.20 The utility of this method was highlighted in syntheses of chiral carboxylic acids that incorporate CF3-bearing quaternary carbon stereocenters (Scheme 8).

Scheme 7.

Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed reductive coupling of methanol with CF3-allenes via hydrogen auto-transfer.

Scheme 8.

Syntheses of enantiomerically enriched carboxylic acids that incorporate CF3-bearing quaternary carbon stereocenters.

Iridium complexes modified by PhanePhos are also effective catalysts for the 2-propanol-mediated reductive coupling of 1,1-disubstituted allenes with fluoral (Scheme 9).21 In this way, branched CF3-substituted secondary alcohols bearing acyclic quaternary carbon stereocenters20 are formed with high levels of anti-diastereo- and enantioselectivity. The utility of this method was illustrated by the construction of CF3-substituted oxetanes and azetidines (Scheme 10). The oxetane formation proceeds via secondary to primary methanesulfonate transfer, which accounts for the divergent diastereoselectivity of these processes. Iridium-PhanePhos complexes were uniquely effective in the allene-mediated C-C coupling described herein.18,21 Investigations into the reaction mechanism suggest the chromatographically stable, cyclometallated iridium-(R)-PhanePhos complex, (R)-Ir-PP-I, is the active catalyst. Generation of the cyclometallated complex in situ provides a slightly more active catalyst that does not incorporate the bidentate acetate counterion, which appears to impede conversion (Scheme 11).

Scheme 9.

Enantioselective iridium-catalyzed reductive coupling of fluoral with allenes mediated by 2-propanol.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of an enantiomerically enriched CF3-substituted oxetane and CF3-substituted azetidine.

Scheme 11.

The catalytically competent cyclometallated iridium-PhanePhos complex (R)-Ir-PP-I.

III. Summary and Outlook

Carbonyl addition has played a fundamental role in chemical synthesis since the inception of organic chemistry as a field. However, traditional methods have typically relied on the use of stoichiometric carbanions, which must be preformed and deployed under cryogenic conditions and incur issues of safety, waste generation and functional group compatibility. By harnessing the reducing power of alcohols, we have demonstrated that carbonyl additional can be accomplished from transient organometallic nucleophiles in the absence of stoichiometric metals under non-cryogenic conditions.3 As summarized herein, adaptation of these methods for the synthesis of chiral organofluorine compounds enables access to novel fluorine-containing compounds that would otherwise be difficult to prepare. For application of this chemistry on scale, it will be important to reduce catalyst loadings, as successfully accomplished in related iridium-catalyzed alcohol aminations.22 The focus of future studies will be on the development of related C-C couplings, including alcohol-mediated carbonyl arylations and related cross-electrophile reductive couplings.

Funding

The Welch Foundation (F-0038) and the NIH (RO1-GM069445) are acknowledged for partial support of this research. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is acknowledged for postdoctoral fellowship support (JT).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- [1].For selected reviews underscoring he prevalence of organofluorine compounds in pharmaceutical and agrochemical ingredients:; (a) Thayer AM ENZYMES AT WORK: Rapid screening and optimization of enzymatic activity, along with available, easy-to-use enzymes, are making biocatalysis a handy tool for chiral synthesis. Chem. Eng. News 2006, 84, 15–25. [Google Scholar]; (b) Müller K; Faeh C; Diederich F Fluorine in Pharmaceuticals: Looking Beyond Intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang J; Sánchez-Roselló M; Aceña JL; del Pozo C; Sorochinsky AE; Fustero S; Soloshonok VA; Liu H Fluorine in Pharmaceutical Industry: Fluorine-Containing Drugs Introduced to the Market in the Last Decade (2001–2011). Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhou Y; Wang J; Gu Z; Wang S; Zhu W; Aceña JL; Soloshonok VA; Izawa K; Liu H Next Generation of Fluorine-Containing Pharmaceuticals, Compounds Currently in Phase II–III Clinical Trials of Major Pharmaceutical Companies: New Structural Trends and Therapeutic Areas. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Meanwell NA Fluorine and Fluorinated Motifs in the Design and Application of Bioisosteres for Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].For selected reviews on the preparation of organofluorine compounds, see: [Google Scholar]; (a) Gong Y Recent Applications of Trifluoroacetaldehyde Ethyl Hemiacetal for the Synthesis of Trifluoromethylated Compounds. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004, 17, 1659–1675. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cahard D; Xu X; Couve-Bonnaire S; Pannecoucke X Fluorine & chirality: how to create a nonracemic stereogenic carbon–fluorine centre? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nie J; Guo H-C; Cahard D; Ma J-A Asymmetric Construction of Stereogenic Carbon Centers Featuring a Trifluoromethyl Group from Prochiral Trifluoromethylated Substrates. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 455–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Furuya T; Kamlet AS; Ritter T Catalysis for fluorination and trifluoromethylation. Nature 2011, 473, 470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Besset T; Schneider C; Cahard D Tamed arene and heteroarene trifluoromethylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5048–5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Studer AA “Renaissance” in radical trifluoromethylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 8950–8958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liang T; Neumann CN; Ritter T Introduction of Fluorine and Fluorine-Containing Functional Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8214–8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Campbell MG; Ritter T Modern Carbon–Fluorine Bond Forming Reactions for Aryl Fluoride Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 612–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Xu X-H; Matsuzaki K; Shibata N Synthetic Methods for Compounds Having CF3–S Units on Carbon by Trifluoromethylation, Trifluoromethylthiolation, Triflylation, and Related Reactions . Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 731–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Yang X; Wu T; Phipps RJ; Toste FD Advances in Catalytic Enantioselective Fluorination, Mono-, Di-, and Trifluoromethylation, and Trifluoromethylthiolation Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 826–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Alonso C; Martinez de Marigorta E; Rubiales G; Palacios F Carbon Trifluoromethylation Reactions of Hydrocarbon Derivatives and Heteroarenes. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1847–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Zhu Y; Han J; Wang J; Shibata N; Sodeoka M; Soloshonok VA; Coelho JAS; Toste FD Modern Approaches for Asymmetric Construction of Carbon–Fluorine Quaternary Stereogenic Centers: Synthetic Challenges and Pharmaceutical Needs. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3887–3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].For selected reviews on alcohol-mediated carbonyl addition, see: [Google Scholar]; (a) Hassan A; Krische MJ Unlocking Hydrogenation for C–C Bond Formation: A Brief Overview of Enantioselective Methods. Org. Proc. Res. Devel. 2011, 15, 1236–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Ketcham JM; Shin I; Montgomery TP; Krische MJ Catalytic Enantioselective C–H Functionalization of Alcohols by Redox‐Triggered Carbonyl Addition: Borrowing Hydrogen, Returning Carbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9142–9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nguyen KD; Park BY; Luong T; Sato H; Garza VJ; Krische MJ Metal-catalyzed reductive coupling of olefin-derived nucleophiles: Reinventing carbonyl addition. Science 2016, 354, aah5133–1–aah5133–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim SW; Zhang W; Krische MJ Catalytic Enantioselective Carbonyl Allylation and Propargylation via Alcohol-Mediated Hydrogen Transfer: Merging the Chemistry of Grignard and Sabatier. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2371–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Holmes M; Schwartz LA; Krische MJ Intermolecular Metal-Catalyzed Reductive Coupling of Dienes, Allenes, and Enynes with Carbonyl Compounds and Imines. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6026–6052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].For selected reviews on alcohol substitution via “borrowing hydrogen” or hydrogen auto-transfer, see: [Google Scholar]; (a) Guillena G; Ramón DJ; Yus M Alcohols as Electrophiles in C–C Bond Forming Reactions: The Hydrogen Autotransfer Process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2358–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hamid MHSA; Slatford PA; Williams JMJ Borrowing Hydrogen in the Activation of Alcohols. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 1555–1575. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nixon TD; Whittlesey MK; Williams JMJ Transition Metal Catalyzed Reactions of Alcohols using Borrowing Hydrogen Methodology. Dalton Trans. 2009, 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dobereiner GE; Crabtree RH Dehydrogenation as a Substrate-Activating Strategy in Homogeneous Transition-Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 681–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guillena G; Ramón DJ; Yus M Hydrogen Autotransfer in the N-Alkylation of Amines and Related Compounds using Alcohols and Amines as Electrophiles. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1611–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yang Q; Wang Q; Yu Z Substitution of Alcohols by N-Nucleophiles via Transition Metal-Catalyzed Dehydrogenation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2305–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Nandakumar A; Midya SP; Landge VG; Balaraman E Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Hydrogen-Transfer Annulations: Access to Heterocyclic Scaffolds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 11022–11034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Huang F; Liu Z; Yu Z C-Alkylation of Ketones and Related Compounds by Alcohols: Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Dehydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 862–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Quintard A; Rodriguez J Catalytic Enantioselective OFF ↔ ON Activation Processes Initiated by Hydrogen Transfer: Concepts and Challenges. Chem. Comm. 2016, 52, 10456–10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Quintard A; Rodriguez J A Step into an Eco-Compatible Future: Iron- and Cobalt-Catalyzed Borrowing Hydrogen Transformation. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Chelucci G Metal-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Pyrroles and Indoles from Alcohols. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 331, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Kim IS; Ngai M-Y; Krische MJ Enantioselective Iridium-Catalyzed Carbonyl Allylation from the Alcohol or Aldehyde Oxidation Level Using Allyl Acetate as an Allyl Metal Surrogate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6340–6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim IS; Ngai M-Y; Krische MJ Enantioselective Iridium-Catalyzed Carbonyl Allylation from the Alcohol or Aldehyde Oxidation Level via Transfer Hydrogenative Coupling of Allyl Acetate: Departure from Chirally Modified Allyl Metal Reagents in Carbonyl Addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14891–14899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) Kim IS; Han SB; Krische MJ anti-Diastereo- and Enantioselective Carbonyl Crotylation from the Alcohol or Aldehyde Oxidation Level Employing a Cyclometallated Iridium Catalyst: α-Methyl Allyl Acetate as a Surrogate to Preformed Crotylmetal Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2514–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao X; Townsend IA; Krische MJ Enhanced anti-Diastereo- and Enantioselectivity in Alcohol-Mediated Carbonyl Crotylation Using an Isolable Single Component Iridium Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2350–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gao X; Zhang YJ; Krische MJ Iridium-Catalyzed anti-Diastereo- and Enantioselective Carbonyl (α-Trifluoromethyl)allylation from the Alcohol or Aldehyde Oxidation Level. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4173–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Karjalainen OK; Passiniemi M; Koskinen AMP Short and Straightforward Synthesis of (–)-1-Deoxygalactonojirimycin. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1145–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Piperidines are the third most prevalent ring system in small molecule drugs: Taylor RD; MacCoss M; Lawson ADG. Rings in Drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen Q; Qing F-L Stereoselective construction of the 1,1,1-trifluoroisopropyl moiety by asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-(trifluoromethyl)allylic alcohols and its application to the synthesis of a trifluoromethylated amino diol. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 11965–11972. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hassan A; Montgomery TP; Krische MJ Consecutive iridium catalyzed C–C and C–H bond forming hydrogenations for the diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of syn-3-fluoro-1-alcohols: C–H (2-fluoro)allylation of primary alcohols. Chem. Comm. 2012, 48, 4692–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Crabtree RH Iridium compounds in catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979, 12, 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cabrera JM; Tauber J; Zhang W; Xiang M; Krische MJ Selection between Diastereomeric Kinetic vs Thermodynamic Carbonyl Binding Modes Enables Enantioselective Iridium-Catalyzed anti-(α-Aryl)allylation of Aqueous Fluoral Hydrate and Difluoroacetaldehyde Ethyl Hemiacetal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9392–9395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Bandini M; Sinisi R; Umani-Ronchi A Enantioselective organocatalyzed Henry reaction with fluoromethyl ketones. Chem. Commun. 2008, 4360–4362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu Y-L; Shi T-D; Zhou F; Zhao X-L; Wang X; Zhou J Organocatalytic Asymmetric Strecker Reaction of Di- and Trifluoromethyl Ketoimines. Remarkable Fluorine Effect. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3826–3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Grassi D; Li H; Alexakis A Formation of chiral fluoroalkyl products through copper-free enantioselective allylic alkylation catalyzed by an NHC ligand. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11404–11406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Aikawa K; Yoshida S; Kondo D; Asai Y; Mikami K Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tertiary Alcohols and Oxetenes Bearing a Difluoromethyl Group. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 5108–5111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Banik SM; William Medley J; Jacobsen EN Catalytic, asymmetric difluorination of alkenes to generate difluoromethylated stereocenters. Science 2016, 353, 51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Bos M; Huang W-S; Poisson T; Pannecoucke X; Charette AB; Jubault P Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Highly Functionalized Difluoromethylated Cyclopropanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 13319–13323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) van der Mei FW; Qin C; Morrison RJ; Hoveyda AH Practical, Broadly Applicable, α-Selective, Z-Selective, Diastereoselective, and Enantioselective Addition of Allylboron Compounds to Mono-, Di-, Tri-, and Polyfluoroalkyl Ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9053–9065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].For a recent review on atropine (d/l-hyoscyamine), see: Rita P; Animesh DK An Updated Overview On Atropa Belladonna L. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2011, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- [16].For reviews on the use of methanol as a C1 feedstock in metal catalyzed C-C coupling, see: [Google Scholar]; (a) Sam B; Breit B; Krische MJ Paraformaldehyde and Methanol as C1 Feedstocks in Metal-Catalyzed C–C Couplings of π-Unsaturated Reactants: Beyond Hydroformylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3267–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Natte K; Neumann H; Beller M; Jagadeesh RV Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Utilization of Methanol as a C1 Source in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6384–6394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moran J; Preetz A; Mesch RA; Krische MJ Iridium-catalysed direct C–C coupling of methanol and allenes. Nature Chem. 2011, 3, 287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Holmes M; Nguyen KD; Schwartz LA; Luong T; Krische MJ Enantioselective Formation of CF3-Bearing All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenters via C–H Functionalization of Methanol: Iridium Catalyzed Allene Hydrohydroxymethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 8114–8117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].For a related iridium-PhanPhos-catalyzed C-C coupling of methanol with 2-substituted dienes, see: Nguyen KD; Herkommer D; Krische MJ Enantioselective Formation of All-Carbon Quaternary Centers via C-H Functionalization of Methanol: Iridium-Catalyzed Diene Hydrohydroxymethylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14210–14213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feng J; Holmes M; Krische MJ Acyclic Quaternary Carbon Stereocenters via Enantioselective Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 12564–12580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schwartz LA; Holmes M; Brito GA; Gonçalves TP; Richardson J; Ruble JC; Huang K-W; Krische MJ Cyclometallated Iridium-PhanePhos Complexes Are Active Catalysts in Enantioselective Allene-Fluoral Reductive Coupling and Related Alcohol-Mediated Carbonyl Additions that Form Acyclic Quaternary Carbon Stereocenters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Berliner MA Dubant SPA; Makowski T; Ng K; Sitter B; Wager C; Zhang Y Use of an Iridium-Catalyzed Redox-Neutral Alcohol-Amine Coupling on Kilogram Scale for the Synthesis of a GlyT1 Inhibitor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2011, 15, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar]