Abstract

Growth in the presence of Emotional Support Animals (ESAs) in our society has recently garnered a substantial amount of attention, both in the popular media and the professional literature. Public media abounds with stories focusing on the increasing number of animals claimed as ESAs, the impact of this growth on society, the industry claiming to certify ESAs, and the various types of animals described as “certified.” The authors propose an assessment model for ESAs certification comprising a four-pronged approach for conducting these types of assessments: (1) understanding, recognizing, and applying the laws regulating ESAs, (2) a thorough valid assessment of the individual requesting an ESA certification, (3) an assessment of the animal in question to ensure it actually performs the valid functions of an ESA, and (4) an assessment of the interaction between the animal and the individual to determine whether the animal’s presence has a demonstrably beneficial effect on that individual. This model aligns with professional ethics, standards of professional practice, and the law and seeks to provide clear guidelines for mental health professionals conducting ESA evaluations.

Keywords: ethics, emotional support animal, ESA, disability, assessment

The pervasive presence of Emotional Support Animals (ESAs) in our society has recently garnered a substantial amount of attention both in the popular media and the professional literature (e.g., Boness, Younggren, & Frumkin, 2017; Younggren, Boness, & Boisvert, 2016). Public media abounds with articles that focus on the increasing number of animals certified as ESAs, the impact of this growth on society, the ESA certification industry, and the various types of animals described as “certified” (Herzog, 2016) - a list that includes squirrels, peacocks, pigs, ducks, monkeys, hamsters, turtles, and even snakes. The novelty evident in such a list requires no explanation and the basis on which some of these animals acquired certification remains a mystery. Taking matters to the extreme, an airline recently fielded a request to allow an ESA to travel with another animal as its own ESA (Matyszczyk, 2018).

Professional publications have detailed concerns about the certification of ESAs, including ethical concerns about whether treating mental health professionalsshould even offer such certifications, particularly given such work constitutes boundary crossings and has little to do with therapy (Younggren, Boness, & Boisvert, 2016). In addition, the issue of whether any scientific basis exists to support the notion that ESAs have a measurable impact on the psychological condition of the person alleging a need “…is inconsistent, sparse and emerging” (Younggren et. al, 2016, p. 4). Existing reports of benefits likely suffer from bias and correlational artifacts (Crossman, 2017; Le Roux & Kemp, 2009). Further, a recent survey study of practicing forensic and clinical mental health practitioners failed to reveal any consensual model for how to evaluate individuals reporting need for an ESA, such as which assessment instruments should be used when conducting such an evaluation (Boness, Younggren, & Frumkin, 2017). As such, this has resulted in a murky state of affairs related to ESAs and ESA evaluations/certifications.

Such certifications have allowed most ESAs to travel with their owners on airlines free of charge and to reside in housing otherwise prohibiting pets without the requirement of a pet deposit or fee. Demands for ESA accommodations have created a burden for airlines, who have tried to cope by adjusting their policies in an attempt to reasonably control the growth of these travel companions on flights (Gilbertson, 2018). In addition, landlords have also begun to tighten up the way they deal with the impact of the growth in ESA certifications by insisting that the presence of any animal conforms to law, meaning that ESAs cannot wander around a building’s common areas and must stay in their owner’s apartment (Disability Rights California, 2014). Clearly, emotional support animal certifications, whether legitimate or not, have significantly affected several sectors of society including travel, public accommodations and housing.

In order to obtain access rights for an ESA, per the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA, 2003), a letter from a treating mental health professional is required. A major difficulty with most ESA certifications involves a general lack of awareness regarding ESA laws on the part of many mental health professionals writing certification letters, as well as a lack of consistent standards for performing appropriate assessments (Boness, Younggren & Frumkin, 2016). Some professionals providing putative assessments and offering certifications online have suffered disciplinary actions by their licensing boards (e.g., State Board of Licensed Professional Counselor Examiners v. Stanford Sutherland, 2016), suggesting a recognition of malfeasance in the practitioner community and need for clearer assessment guidelines within the field of professional psychology.

The Ethical Challenge

In spite of the fact that the professional literature cautions mental health professionals about providing certification letters for their own clients (e.g., Younggren et al., 2016), many psychotherapists and health care professionals continue to perform this service. In addition, the popular media is replete with evidence that the number of people asserting needs for ESAs is striking and continuing to increase, placing a burden on those charged with accommodating such requests. The ethical issues inherent in this discussion fall into three primary categories: competence, assessment practices, and boundary problems. Understanding the laws and policies that regulate ESAs (described in more detail below) comprises part of the competence problem, and is well described elsewhere (e.g., Younggren, Boness, & Boisvert, 2016). Additionally, mental health professionals who lack full awareness of the law will likely fail to recognize that writing such letters constitutes a disability determination that becomes a part of the individual’s clinical records. Such mental health professionals may also fail to fully grasp the elements of an assessment necessary to confirm ESA eligibility or may lack the skills needed to perform a formal and comprehensive disability assessment. While these issues are important, they have been elaborated on previously (see Boness et al., 2017 and Younggren et al., 2016). Therefore, the remainder of the manuscript focuses on the ethical concerns related to boundary issues.

The boundary issue arises when a mental health professional agrees to evaluate a psychotherapy client for some purpose not directly related to the treatment, in this case, for a psychological disability. In making such a request, the individual may expect that the mental health professional who has shown them support and positive regard, will comply in advocating for them by drafting the letter. In many cases, providing a documentation letter requested by a given individual may pose no ethical problem for a treating mental health professional. For example, letters confirming the fact that an individual has regularly attended therapy sessions, documenting a diagnosis as a focus of treatment, or providing proof of payment for services for valid medical expense purposes provide instances in which providing a simple letter in response to an individual’s request poses no boundary problem. Documenting the disability necessary to support a lawful need for an ESA, however, rises to another level of assessment.

The psychotherapist, who must focus on maintaining a therapeutic alliance, will become compromised when attempting to avoid bias in conducting an objective evaluation (Greenberg & Shuman, 1997). Will the psychotherapist simply determine ad hoc that the individual warrants such a letter based on their work together, without an additional focused assessment? Will the psychotherapist recognize their own potential biases that might preclude an objective assessment? What will happen to the therapeutic relationship if the psychotherapist’s assessment does not support the individual’s wishes? These are all questions that demand thorough consideration before assuming the role of assessor in this context.

In the pages that follow we will document the key components necessary to establish the need for an ESA, consistent with professional standards of assessment and integrity. While some contend that ESA assessments can be conducted by treating therapists, consistent with the wording of the law, we hold that conducting this type of an assessment creates a risky role conflict for treating psychotherapists and has very little to do with psychotherapy (Younggren, Boness, & Boisvert, 2016). Consequently, such evaluations, which are clearly forensic in nature (see Younggren, et. al.), should be conducted by individuals having no other relationship with the person seeking to qualify for ESA accommodations. However, as with any evaluation intended to answer a legal question, the mental health professional must own the responsibility to assess their personal competence, biases, integrity, and potential consequences to the therapeutic relationship in agreeing to consider preparing documentation to support the need for an ESA.

The Emotional Support Animal Evaluation Model

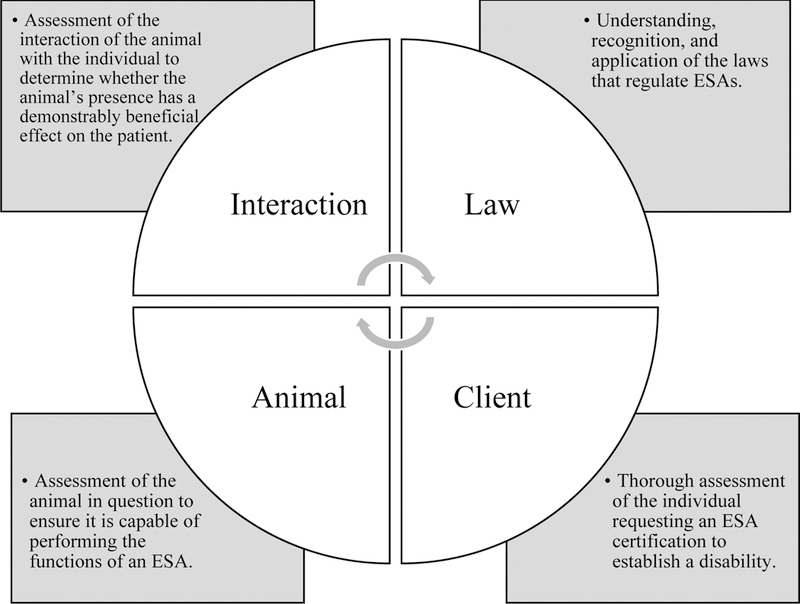

Despite the rapid increase in ESA requests and certifications, there remain no extant guidelines for conducting such assessments. The lack of clear guidelines has resulted in a highly ambiguous state of affairs whereby current ESA certifications have no standards against which they can be compared and judged as valid or not. Given the need for standard guidelines, we propose the following model for mental health professionals who agree to conduct ESA evaluations. This model is comprehensive, arguably consistent with the existing standards of practice for psychological assessments (e.g., Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, American Psychological Association Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychology, American Academy of Psychiatry and Law [AAPL] Practice Guidelines for the Forensic Evaluation of Psychiatric Disability) and comports with the requirements of law. We believe that appropriate certification must include four related components: (1) understanding, recognition, and application of the laws that regulate ESAs, (2) a thorough assessment of the individual requesting an ESA certification, (3) an assessment of the animal in question to ensure it is capable of performing the valid functions of an ESA, and (4) an assessment of the interaction between the animal and the owner to determine whether the animal’s presence has a demonstrably beneficial effect on the owner. This model is depicted in Figure 1 which represents the four components as cyclical in nature rather than in a step-by-step process. The cyclical nature of the process aligns with our belief that each component of the model should inform the others, rather than occurring in a step-by-step fashion. Below we elaborate on the relevant components of our ESA assessment model. For each component, we articulate relevant guidelines. These guidelines are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Standard Model for Mental Health Professionals Conducting Emotional Support Animal Evaluations. This figure summarizes the main components of Emotional Support Animal evaluations. The cyclical nature of the figure is consistent with our belief that each component of the model should inform the others, rather than occurring in a step-by-step fashion.

Table 1.

Summary of Guidelines for Mental Health Professionals Conducting Emotional Support Animal Evaluations

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| Guideline 1 | The mental health professional must be able to understand, recognize, and apply the laws that regulate Emotional Support Animals. |

| Guideline 2 | The mental health professional should conduct a thorough assessment of the individual requesting an Emotional Support Animal certification in order to establish a disability and disability-related need. |

| Guideline 2a | A necessary component of the comprehensive disability assessment includes an evaluation of malingering. |

| Guideline 3 | The mental health professional should consider if the animal in question is capable of performing the functions of an Emotional Support Animal |

| Guideline 3a | When necessary, the mental health professional should seek collateral information regarding the capability of the animal in question to serve as an Emotional Support Animal. |

| Guideline 4 | The mental health professional should assess the interaction of the client with the animal to determine whether the animal’s presence has a demonstrably beneficial effect on the patient |

Note. This table of guidelines is intended to serve as a quick-reference and should be accompanied by the full descriptions provided in the main of the manuscript.

The Law

Guideline 1: The mental health professional must be able to understand, recognize, and apply the laws that regulate Emotional Support Animals.

We contend a mental health professional intending to engage in the certification of an ESA for a given individual must have solid familiarity with relevant law. Younggren, Boness, and Boisvert (2016) discussed, in detail, the confusion that often arises with dealing with ESAs and how the use of these animals is, or is not, authorized by law. First, there is no legal clarity regarding which types of animals are covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). As a civil rights law prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities, the ADA aims to ensure equal opportunities in access to public accommodations, employment, and transportation (ADA, 2018). The ADA covers Service Animals (SAs) and Psychiatric Service Animals (PSAs) but not does not cover ESAs. Therefore, the ADA does not directly apply to or entitle the use of an ESA. (For a thorough discussion of the different types of service animals see Younggren et al., 2016.)

In the spirit of clarifying any confusion, readers should note that only two laws directly apply to the use of ESAs in public accommodations: the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA, 2003) and the Fair Housing Act (FHA, 1968). Under the ACAA, the ESA must be allowed to accompany their handler in the main cabin of an aircraft at no charge. As applied to the FHA, the ESA can stay with its owner in a housing unit that otherwise prohibits pets and the landlord must not impose a fee of any sort related to this special accommodation (Wisch, 2015). The ACAA and FHA describe specific requirements that must be met before an ESA is granted these protections (see Younggren, Boness, & Boisvert, 2016). First, the individual must have a psychiatric diagnosis consistent with the DSM-5 and assigned by a licensed mental health professional. Second, the person must qualify as disabled based on the psychological condition and the presence of the animal must ameliorate some of the symptoms of that disability. They key criterion in the second requirement is the word “disabled.” Tran-Lein (2013), an attorney, emphasized that the ESAs must “…perform many disability-related functions, including, but not limited to, providing emotional support to persons with disabilities who have a disability-related need for such support… but they must (emphasis added) provide a disability-related benefit to such individuals” (p. 2). The definition of disability becomes critical because the person allowed this exception must, by law, qualify as mentally or emotionally disabled by their psychological condition.

Disability, broadly defined, refers to a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities (24 CFR 8.3). For the psychologist working with an individual, disability as it applies to ESA certifications is not simply a matter of discomfort experienced by the individual. Disability, in this case, describes a psychological condition that substantially interferes with the individual’s ability to perform major life activities. Disability does not mean the individual has an attachment to the ESA, feels happier in proximity to the ESA, or just wants to accompany the animal, which is usually their pet. It means that the person requires the presence of the animal to function or remain psychologically stable. Arguably, then, the individual who receives an ESA certification for a psychological disability must undergo a comprehensive assessment which, as a result, allows the qualified assessor to describe the exact nature of the disability and how the presence of the animal impacts that disability.

Assessment of Client

Guideline 2: The mental health professional should conduct a thorough assessment of the individual requesting an Emotional Support Animal certification in order to establish a disability and disability-related need.

Remain mindful that ESA certifications include a disability determination (Younggren et al., 2016). Those undertaking such an evaluation must, therefore, understand the definition of a disability, how to assess the condition, and how to determine the manner in which the ESA measurably assists the disabled person. This can pose confusion because the term “disability” has more than one legal definition. That said, one of the most commonly used definitions of disability is that found in the Social Security Act (SSA) which defines a disability as “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) which can be expected to result in death or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months” (SSA, 2012). The critical point to glean from this definition is that a disability determination is not a casual opinion about a person’s psychological condition, but rather a formal determination of “mental impairment” that relates to a “significant deviation, loss or loss of use of any body structure or body function in an individual with a health condition or a disease” (Anderson & Cocchiarella, 2008, p. 5). Examples of specific criteria for mental disabilities may be found on the Social Security web site (for adults see: www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/12.00-MentalDisorders-Adult.htm; for children see: www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/112.00-MentalDisorders-Childhood.htm).

The next question of ethical importance involves how one conducts a competent disability evaluation. The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (Anafang, Gold & Meyer, 2018) has taken the position that the purpose of a disability evaluation involves tying the impairments to a mental health condition. In so doing, the Academy contends that an appropriate evaluation includes a review of records and collateral information, a standard examination of the subject of the evaluation, an examination of the relationship of the impairment to the “mental disorder,” a review of alternate explanations for the alleged disability, and a formulation of opinions (Anfang, Gold & Meyer, 2018). The American Psychological Association has not produced a similar document on conducting disability evaluations, however, we can turn to the Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychology for guidance (APA, 2011). According to the SGFP, when a psychologist conducts a forensic assessment of a person, they use multiple sources of information (SGFP 9.02), strive to utilize appropriate methods and procedures in their work, and seek information that will differentially test plausible rival hypotheses (SGFP, 9.01).

Some of the questions that should be answered before the certification of a disability lend themselves to evaluation with psychological test data, while behavioral assessment may prove useful in evaluating others. For example, does the presence of the ESA allow the individual to more effectively perform activities of daily living (ADLs) commonly done by others, reduce anxiety sufficiently to yield measurable improvements in concentration, or facilitate improved social interactions with other people?

Guideline 2a: A necessary component of the comprehensive disability assessment includes an evaluation of malingering.

An additional component of this examination, per AAPL guidelines for Forensic Evaluation and Psychiatric Disability (Gold et al., 2008), includes assessing for malingering or “faking bad.” This becomes particularly necessary if the claim is based primarily on self-report, given that malingering commonly occurs in disability determinations (e.g., some authors have noted evidence for probable malingering in over 30% of disability or worker’s compensation cases [Mittenberg et al., 2002]). Given disability evaluations involve complex, multifactorial assessments of an individual’s psychological condition, they should typically include some assessment of malingering.

In any case, the mental health professional will need to document three phenomena to comport with this guideline: the presence of a mental disorder, the disabling nature of the symptoms, and the amelioration of some symptoms or level of the disability’s severity by the presence of or interaction with an ESA. These phenomena cannot be adequately described without also assessing the client’s interaction with the animal intended to be an ESA.

Assessment of the Animal

Guideline 3: The mental health professional should consider if the animal in question is capable of performing the functions of an Emotional Support Animal.

Another necessary aspect of an ESA evaluation involves assessing the temperament of the animal that meets the individual’s need for emotional support. Though mental health professionals are more than likely not trained or competent to directly assess animal temperaments, consideration of this factor via collateral information is nonetheless critical to ESA certification. This is particularly warranted because some animals simply do not match the purported role of an ESA well. With recent evidence of companion animal attacks on other airline passengers (e.g., Hefferman, 2018) and some animals’ inability to cope with the stresses of exposure to the public and alien environments (e.g., air travel, shopping areas, or other highly stimulating environments that include encounters with unknown people), the reality is that not all animals can reasonably serve as an ESA (Mashable, 2019).

Recall that in order to meet criteria for certification, the presence of the animal must ameliorate some symptom(s) of the disability or provide a disability-related benefit to the individual. Some animals simply cannot do this, and some may be able to do so in certain contexts or environments but not in others. Take, for example, the situation of a dog who purportedly reduces the anxiety of its owner. Perhaps the dog achieves this effect via its calm, steady presence; or by leaning steadily into his/her owner when the individual starts to panic and allowing the owner to pet him/her; or by being playful and silly and distracting the owner from his/her own anxiety. But when brought into a foreign environment that is scary or overwhelming (such as a busy airport), that same dog might no longer be able to provide the steady presence that was so calming to the individual at home.

In fact, the media is replete with examples of dogs becoming so scared they defecate, vomit, or aggress toward others (Hefferman, 2018). If the animal itself is so overwhelmed, scared, or aggressive that it’s behaving in a distressed, uncharacteristic, possibly attacking manner, it is highly unlikely that the animal has the ability (in that state) to provide a grounded steady presence for the individual. To the contrary, the animal’s presence may actually serve to increase the individual’s distress as the disabled person witnesses their beloved animal suffer and/or attack others or as the person must attempt to manage the potential angry responses by other humans distressed or harmed by the animal’s inappropriate behavior. Repeated instances of such behavior, while obviously not helpful to the animal, may also be damaging for the animal-human relationship (Patronek et al., 1996, Kwan and Bain, 2013). From this perspective, consideration of the animal’s temperament should also be context dependent; that is, taking into consideration the environment in which the animal is supposed to serve as an ESA. Living in a quiet, fairly predictable home environment is far less stressful and more readily managed by most animals, than going into public, sometimes chaotic, environments with lots of strangers and unpredictability (e.g., airports, flying on an airplane). An animal may be able to serve the role of ESA in the former environment, but not in the latter.

Guideline 3a: When necessary, the mental health professional should seek collateral information regarding the capability of the animal in question to serve as an Emotional Support Animal.

It is incumbent on the mental health professional to consider the temperament of the animal and obtain reliable collateral information to support a conclusion that the animal is able to serve the ESA function in the environment in which it will be placed. Such collateral information could come from a variety of sources. For example, with dogs, one option is to obtain documentation that the dog has passed the Canine Good Citizen (CGC) Test (https://www.akc.org/products-services/training-programs/canine-good-citizen/), which tests for a fairly basic standard of temperament and decorum in public environments. The CGC is a prerequisite for many therapy dog groups, is encouraged by homeowner’s insurance companies, and is sometimes required by landlords. Alternatively, information could be obtained from an animal trainer, animal behaviorist, or veterinarian who has assessed the animal and can speak to the animal’s temperament and likely behavior in novel, potentially stressful environments. The mental health clinician can then use such information when considering whether the animal is able to fulfill the role of an ESA in specific contexts, in much the same manner that forensic clinicians rely on collateral sources in a multitude of forensic or administrative evaluations. What is key here is to respect the reality that the assessment of the animal is beyond the skill set of most mental health professionals and that this information usually needs to be gleaned from other sources unless the professional has demonstrated competence in these types of assessments. In cases where the Emotional Support Animal has not been evaluated and collateral information is not available, the mental health professional must consider how this severely limits the comprehensiveness of the ESA evaluation and any resulting certification.

Assessment of Client-Animal Interaction

Guideline 4: The mental health professional should assess the interaction of the client with the animal to determine whether the animal’s presence has a demonstrably beneficial effect on the patient.

It is important for the ESA evaluation to include an assessment of the client-animal interaction in order to determine whether there is indeed beneficial impact of the animal’s presence on the individual. This “beneficial impact” should be directly relevant to the individual’s disability and disability-related impairment. This step is consistent with the forensic or quasi-forensic nature of the assessment and with general standards and ethics for conducting such evaluations (e.g., Greenburg and Shuman, 1997; Specialty Guidelines for Forensic Psychologists, 2012). It is not sufficient to simply take the client’s word that the animal helps or to simply assume it is so because the individual loves their pet. Part of the necessary distinction requires differentiation between someone who is emotionally attached to and enjoys the company of their pet (which could include most pet owners) versus individuals who must rely on the animal for reduction or alleviation of disability related symptoms. In order to do this, it is important to first assess whether there is a bona fide disability, and if so, to identify what the disability is and in what specific way the animal is thought to have an impact on that disability.

Then, we contend, an observation of the individual and animal together is essential for ascertaining whether a disability-related amelioration of symptoms occurs. There must be opportunities for the mental health professional to see the individual both with and without the animal present so as to compare the individual’s mental status and comportment in both contexts. Some things to consider during the observation of the individual and animal together include: Does the individual interact with the animal in some specific way and, if so, what is the effect on the individual? Is there any change in the individual when the animal is present versus when it is not? What evidence can the mental health professional identify and describe to support the conclusion that the animal is providing a disability-related benefit? What disability-related symptoms are being impacted by the animal and in what way? Are the disability-related symptoms decreased or mitigated in some way when the animal is present? Given the answers to these questions do rely on clinical judgment, the mental health professional could also include formal assessment instruments that measure the reduction of the disability-related symptoms. For example, the mental health professional may use a standardized, objective measure of symptomology directly relevant to the disability (e.g., the GAD-7 for anxiety symptoms) in a pre-post fashion. That is, the individual’s anxiety symptoms are assessed without the animal and again in the presence of the animal to determine if there is any amelioration of symptoms and related impairment. The ability to answer such questions is necessary for completing a comprehensive ESA evaluation.

Unintended Consequences to Consider

When a mental health professional conducts a formal disability assessment, that report and associated data become a part of the individual’s medical records. A finding of mental disability can lead to subsequent adverse consequences for the individual. Questions about mental disability can legitimately be asked as qualifications in certain employment circumstances (e.g., child care, teaching, or public safety job screening) or licenses (e.g., school bus driver or firearms license). In some states a, psychologist may have a reporting obligation to certain state agencies upon finding an individual mentally disabled. For example, Illinois licensed psychologists may have a mandatory obligation to notify the Illinois Department of Human Services Firearm Owners Identification (FOID) Mental Health Reporting System (430 ILCS 65), upon finding some individuals mentally disabled. The question of mental disability will come up if the individual seeks government security clearance, and in some cases life or disability insurance. Obtaining a disability finding and subsequently failing to report it on certain applications (e.g., for employment, insurance, or security clearance) may have serious consequences for the individual. Documentation of mental disability may also become a factor in subsequent child custody disputes. As part of the informed consent process, therefore, the mental health professional has an ethical obligation to alert the individual to the potential adverse consequences of carrying a mental disability finding in their health care records and take care to ensure the individual understands the long-term risks that go with receiving a psychiatric disability.

Discussion

The purpose of the current paper was to delineate a seminal model for conducting comprehensive ESA evaluations. Our model, intended for use by mental health professionals, argues that ESA evaluations must include four related components: (1) recognition and application of laws that regulate ESAs, (2) a thorough disability assessment of the person requesting the ESA certification, (3) an assessment of the animal, and (4) an assessment of the client-animal interaction and the specific disability-related function the animal serves. This model is consistent with standards of psychological assessment and requirements of the law and, therefore, the absence of any of these four components results in an ESA certification that is incomplete.

The ESA assessment model offered here serves as an important risk-management strategy. Previous work has demonstrated the potential ethical and legal issues relevant to mental health providers writing ESA evaluation letters (Younggren et al., 2016) and a general lack of awareness of these issues among professionals (Boness et al., 2017). This model, therefore, aids mental health professionals in ensuring they are upholding the ethical and legal standards of the profession when deciding whether or not to engage in such an evaluation, and, when applicable, conducting such evaluations. It is our belief that the use of this model will also aid in reducing the negative impact illegitimate ESA requests have on society, particularly in the cases of air travel and housing, while also encouraging the upmost professional standards are maintained.

As with most models, this should be used as a guiding framework, making necessary adjustments and decisions where needed. While we have intended to be broad in describing the requirements of a comprehensive ESA evaluation, the way in which this information is acquired, measured, and assessed may vary based on each case. For example, while we have argued the importance of assessing for malingering, we intentionally do not offer suggestions regarding specific assessment instruments. This omission is intentional given that such a decision should be specific to the referral question and case at hand. Similarly, assessment of the animal’s temperament may vary based on the type of animal in question, the resources available in one’s area, and the disability-related benefit they are claiming to provide. Consider this model dynamic in nature and intended to serve as a starting place for identifying the core components of a thorough ESA evaluation, rather than offering guidance on the specific tools and techniques necessary for a comprehensive evaluation. This is why it is particularly important to ensure that mental health professionals have, or take the necessary steps to acquire (e.g., through training, consultation, or similar activities), competence related to the components outlined by the model (e.g., the law, disability assessment).

Given the complexity of conducting comprehensive ESA evaluations, it is our hope that this model will provide mental health professionals with a clear starting place while also safeguarding them against potential ethical or legal pitfalls. As more research on ESAs continue to emerge and the role of the mental health professional becomes clearer, particularly as elucidated by the law, it is possible that new considerations will need to be incorporated into the current model. In the meantime, the current model is intended to serve as the first set of guidelines for conducting comprehensive ESA assessments.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey N. Younggren, University of New Mexico

Cassandra L. Boness, University of Missouri

Leisl M. Bryant, Private Practice

Gerald P. Koocher, Quincy College

References

- Americans with Disabilities (ADA) Act National Network. (2018). What is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)? Retrieved from https://adata.org/learn-about-ada

- Andersson GBJ & Cocchiarella L (2008). American Medical Association: Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment (Ed 6), Chicago IL: AMA [Google Scholar]

- Anfang SA, Gold LH, and Meyer D (2018). AAPL practice resource for the Forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, Online March 2018, 46 (1 Supplement), S2–S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boness CL, Younggren JN, & Frumkin IB (2017). The certification of emotional support animals: Differences between clinical and forensic mental health practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48(3), 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman MK (2017, Effects of interactions with animals on human psychological distress, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(7), 761–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disability Rights California. (2014). Psychiatric service and emotional support animals. Retrieved from http://www.disabilityrightsca.org/pubs/548301.pdf

- Ensminger JJ, & Thomas JL (2013). Writing letter to help patients with service and support animals. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 13, 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson D (2018), Spirit Airlines tightens rules on emotional support animals. USA Today Oct 14, 2018, (I know this is not right) htps://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/flights/2018/10/03/sprit-airlines

- Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, Metzner JL, Price M, Wall BW& Zonana HV. (2008). AAPL Practice Guideline for the Forensic Evaluation of Psychiatric Disability. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 36(4), S3–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SA, & Shuman DW (1997). Irreconcilable conflict between therapeutic and forensic roles. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 28, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan D (2018, November, 13), Comfort Animals’ Do Not Belong In An Aircraft Cabin; Regulators May Act Soon To Address The Problem, Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidheffernan1/2018/11/13/comfort-animals-do-not-belong-in-an-aircraft-cabin-regulators-may-act-soon-to-address-the-problem/#513121fb4aba

- Herzog H (2016) Emotional Support Animals: The therapist’s dilemma, retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/animals-and-us/201607/emotional-support-animals-the-therapists-dilemma, Psychology Today, July 2016.

- Housing and Urban Development 24 CFR 8.3 Subtitle A (4–1-04 Version).

- Mashable (2019). A complete guide to airline policy on emotional support animals. Retrieved from https://mashable.com/2018/02/27/emotional-support-animal-traveling-airplane-policy/#M_oDujiXR5qsbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb

- Matyszczyk C (2018). On this United Airline’s flight, an emotional support animal had its own emotional support animal. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/chris-matyszczyk/on-a-united-airlines-flight-an-emotional-support-animal-had-its-own-emotional-support-animal.html

- Miller Z (2018). 10 dog breeds that may make great emotional support animals, Insider, Nov. 15, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.thisisinsider.com/best-dog-breeds-emotional-support-animals-2018-10?utm_source=email&utm_medium=referral&utm_content=topbar&utm_term=desktop.

- Mittenberg W, Patton C, Canyock EM, & Condit DC (2002). Base rates of malingering and symptom exaggeration. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 24, 1094–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State Board of Licensed Professional Counselor Examiners v. Stanford Sutherland (2016) Retrieved from https://www.dora.state.co.us/pls/real/ddms_public.display_document?p_section=DPO&p_source=ELIC_PUBLIC&p_doc_id=473699&p_doc_key=C9581B58DF08B56A95AF03C3B36FB50C

- Tran-Lien A (2013). Reasonable accommodations and emotional support animals, The Therapist, January/February, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.camft.org/COS/Resources/Attorney_Articles/Ann/Reasonable_Accommodations_and_Emotional_Support_Animals.aspx.

- United States Social Security Administration Office of Disability Programs: Disability Evaluation Under Social Security. Retrieved from https://www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/general-info.htmonOctober25, 2018.

- Wisch R (2015). FAQ’s on emotional support animals. Retrieved from https://www.animallaw.info/article/faqs-emotional-support-animals

- Younggren JN, Boisvert J and Boness C (2016). Examining emotional support animals and role conflicts in professional psychology. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 47(4), 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]