Abstract

The neuronal mechanisms contributing to the generation of involuntary muscle contractions (spasms) in humans with spinal cord injury (SCI) remain poorly understood. To address this question, we examined the effect of Achilles and tibialis anterior tendon vibration at 20, 40, 80, and 120 Hz on the amplitude of the long-polysynaptic (LPR, from reflex onset to 500 ms) and long-lasting (LLR, from 500 ms to reflex offset) cutaneous reflex evoked by medial plantar nerve stimulation in the soleus and tibialis anterior and reciprocal Ia inhibition between these muscles in 25 individuals with chronic SCI. We found that Achilles tendon vibration at 40 and 80 Hz, but not other frequencies, reduced the amplitude of the LLR in the tibialis anterior but not the soleus muscle without affecting the amplitude of the LPR. Vibratory effects were stronger at 80 compared with 40 Hz. Similar results were found in the soleus muscle when the tibialis anterior tendon was vibrated. Notably, tendon vibration at 80 Hz increased reciprocal Ia inhibition between antagonistic ankle muscles and vibratory-induced increases in reciprocal Ia inhibition were correlated with decreases in LLR, suggesting that participants with a larger suppression of later cutaneous reflex activity had stronger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonistic muscle. Our study is the first to provide evidence that tendon vibration suppresses late spasm-like activity in antagonist but not agonist muscles, likely via reciprocal inhibitory mechanisms, in humans with chronic SCI. We argue that targeted vibration of antagonistic tendons might help to control spasms after SCI.

Introduction

Approximately 80% of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) experience involuntary muscle contractions (spasms) in muscles innervated at or below the level of injury (Little et al., 1989). Spasms commonly interfere with daily activities and are considered problematic by the majority of people who experience them (Little et al., 1989; Skold et al., 1999). Animal (Bennett et al., 2001) and human (Gorassini et al., 2004) studies showed that spasms are generated by activation of persistent inward currents (PICs) in motoneurons. PICs prolong the firing of motoneurons, which persists even if the membrane potential falls below what was needed for initial recruitment. Recent evidence also showed that neurons involved in the central pattern generator (CPG) circuitry can contribute to the development of spasms (Lin et al., 2019). Thus, the complex and widespread pattern of leg movements described during spasms in humans with chronic SCI (Mayo et al., 2017) can result from changes in a variety of spinal circuits (D’Amico et al., 2014).

One way to make inferences about the neuronal mechanisms contributing to spasms is by examining the cutaneous reflex. Cutaneous reflexes are amplified in animal models of SCI (Bennett et al., 2004; Rank et al., 2011). Note that the amplitude of the long-polysynaptic (LPR, 40–500 ms) component of the cutaneous reflex evoked by caudal nerve trunk stimulation likely reflects the prolonged polysynaptic excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) and Ca2+ PICs (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011) whereas the long-lasting component (LLR, 500–5,000 ms) is likely to be mediated entirely by Ca2+ PICs (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011). Cutaneous reflexes are also amplified in humans with SCI (Kawamura et al., 1989; Gorassini et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2010; D’Amico et al., 2013; Butler et al., 2016). In individuals with different severity of SCI the amplitude of the LLR, but not the LPR, is substantially diminished by cyproheptadine – a 5-HT inverse agonist used to inhibit PIC activation (Murray et al., 2010). In addition, activation of motoneurons during non-volitional muscle spasms in humans with chronic SCI is driven by PICs intrinsic to the motoneuron and not by simple elevated synaptic inputs (Gorassini et al., 2004). A critical question is how to suppress the LLR in humans with SCI? In control subjects, prolonged tendon vibration decreases the resting discharge rate of muscle spindles and the short latency component of the stretch reflex in lower-limb muscles (Ribot-Ciscar et al., 1998; Shinohara, 2005). In humans with SCI, repeated activation of sensory afferents projecting to motoneurons might be useful to modulate symptoms of hyperexcitability. For example, whole body vibration has been shown to decrease at times stretch reflex excitability in individuals with SCI (Estes et al., 2018). Note that in control (Ritzmann et al., 2018) and SCI (Perez et al., 2004) participants, vibration increases reciprocal Ia inhibition in an antagonistic muscle. Vibration of a muscle or tendon can inhibit antagonist motoneuron firing (MacDonell et al., 2010) and generate inhibitory post-synaptic potentials in antagonist motoneurons via Ia interneurons (Heckman & Binder, 1991). PICs are sensitive to reciprocal Ia inhibition (Kuo et al., 2003; Hyngstrom et al., 2007; Johnson & Heckman, 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that tendon vibration attenuates spasm-like cutaneous reflex activity in antagonist muscles via reciprocal Ia inhibitory mechanisms following chronic SCI.

To test our hypothesis, we used vibration over the Achilles and tibialis anterior tendon on separate trials and examined their effect on the amplitude of a cutaneous reflex evoked by medial plantar nerve stimulation in the soleus (SOL) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles, and tested the strength of reciprocal Ia inhibition between these muscles in humans with chronic SCI. We found that tendon vibration suppressed late spasm-like cutaneous reflex activity in antagonist muscles and SCI participants with larger suppression showed larger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonist muscle.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Twenty-five individuals (mean age 40.6±15.8 years, 4 women; Table 1) with SCI participated in the study. All participants gave informed consent to experimental procedures, which were approved by the local ethics committee at the University of Miami in accordance with guidelines established in the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB protocol #20170222). Participants had a chronic injury (≥1 year) and were classified using the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) exam as having a cervical (C2-C8; n=13) or thoracic (T4-T11; n=12) SCI and by the American Spinal Cord Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) as AIS A (n=9), AIS B (n=1), AIS C (n=8) or AIS D (n=7). Spasticity was assessed using the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS). The frequency of spasms was assessed using the Penn Frequency Scale (Penn et al., 1989) and the severity of spasms was assessed using a 3-point scale (described below; Priebe et al., 1996; Mayo et al., 2017). We measured the effect of tendon vibration over the Achilles or TA tendon on the amplitude of the cutaneous reflex evoked by medial plantar nerve stimulation in the TA and SOL and reciprocal Ia inhibition between these muscles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with spinal cord injury

| Age (Yrs) | Time Since Injury (Yrs) | Sex | Injury Level | AIS | TA Spasticity (MAS) | SOL Spasticity (MAS) | Spasm Frequency | Spasm Severity | Spasm Medication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 6 | M | C2 | D | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | BAC & DIAZ |

| 2 | 42 | 27 | F | C2 | D | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | BAC |

| 3 | 71 | 9 | M | C2 | D | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | BAC |

| 4 | 21 | 3 | F | C4 | D | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | NC |

| 5 | 43 | 13 | M | C4 | D | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | BAC |

| 6 | 29 | 3 | M | C4 | C | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | NU |

| 7 | 20 | 2 | F | C5 | C | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | BAC |

| 8 | 37 | 3 | M | C5 | C | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | NC |

| 9 | 61 | 2 | M | C5 | D | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | BAC |

| 10 | 54 | 5 | M | C5 | A | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | NC |

| 11 | 60 | 16 | M | C5 | D | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | BAC |

| 12 | 25 | 4 | M | C6 | A | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | BAC |

| 13 | 39 | 3 | M | C7 | C | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | NC |

| 14 | 30 | 3 | M | T4 | A | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | BAC |

| 15 | 58 | 3 | M | T4 | A | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | NC |

| 16 | 47 | 15 | F | T4 | C | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | BAC |

| 17 | 61 | 41 | M | T5 | C | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | NU |

| 18 | 46 | 18 | M | T5 | A | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | BAC |

| 19 | 45 | 24 | M | T5 | A | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | BAC |

| 20 | 52 | 17 | M | T5 | A | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | NC |

| 21 | 23 | 2 | M | T6 | C | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | NU |

| 22 | 57 | 20 | M | T6 | A | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | NU |

| 23 | 26 | 4 | M | T7 | A | 0 | 4 | 3 | 2 | NU |

| 24 | 28 | 7 | M | T9 | B | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | NC |

| 25 | 18 | 1 | M | T11 | C | 0 | 2 | 4 | 2 | NU |

AIS=American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale, BAC=Baclofen, C=Cervical, DIAZ=Diazepam, F=Female, M=Male, MAS=Modified Ashworth Scale, NC=Not Currently Using, NU=Never Used, SOL=Soleus, T=Thoracic, TA=Tibialis Anterior, Yrs=years

MAS.

To evaluate the magnitude of spasticity, participants laid in a semi-supine position with the trunk at 30° angle. A neutral position reduces the risk of increasing increases in spasticity related to the resting length of rectus femoris (de Azevedo et al., 2015). Resistance to a manual passive muscle stretch of the ankle plantarflexors and dorsiflexors was evaluated using a five-point scale (0=no increase in tone, 1=slight increase in tone with a catch and release or minimal resistance at the end of range, 2=more marked increased tone through most of the range of movement but affected parts easily moved, 3=considerable increase in tone and passive movement difficultly, and 4=affected parts rigid; Bohannon & Smith, 1987). All MAS assessments were evaluated by the same experienced rater.

Spasms frequency and severity.

Using the Penn Frequency Scale, participants rated the frequency that they experience spasms using a five-point scale (0=no spasms, 1=spasms only induced by stimulation, 2=spontaneous spasms occurring less than once per hour, 3=spontaneous spasms occurring 1 to 10 times per hour, 4=spontaneous spasms occurring more than 10 times per hour). Using a 3-point scale, participants rated the severity of their spasms (0: Mild, 1: Moderate, 2: Severe).

Electromyographic (EMG) recordings.

EMG was recorded from the TA and SOL muscles, with surface electrodes (2 cm diameter, Ag/AgCl electrodes; ConMed Corp., Utica, NY). Electrodes were placed 2 cm apart over the muscle belly. For the TA, the electrodes were placed one-third of the distance between the fibular head and the medial malleolus. For the SOL, the proximal electrode was placed 3 cm distal to the medial gastrocnemius muscle on the midline of the leg. A ground electrode was placed over the patella. EMG signals were amplified (P511 amplifier; Natus Neurology-Grass, West Warwick, RI), filtered (30Hz to 1kHz), and sampled at 3000Hz (1401 interface, Signal v6, Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England).

Tendon vibration.

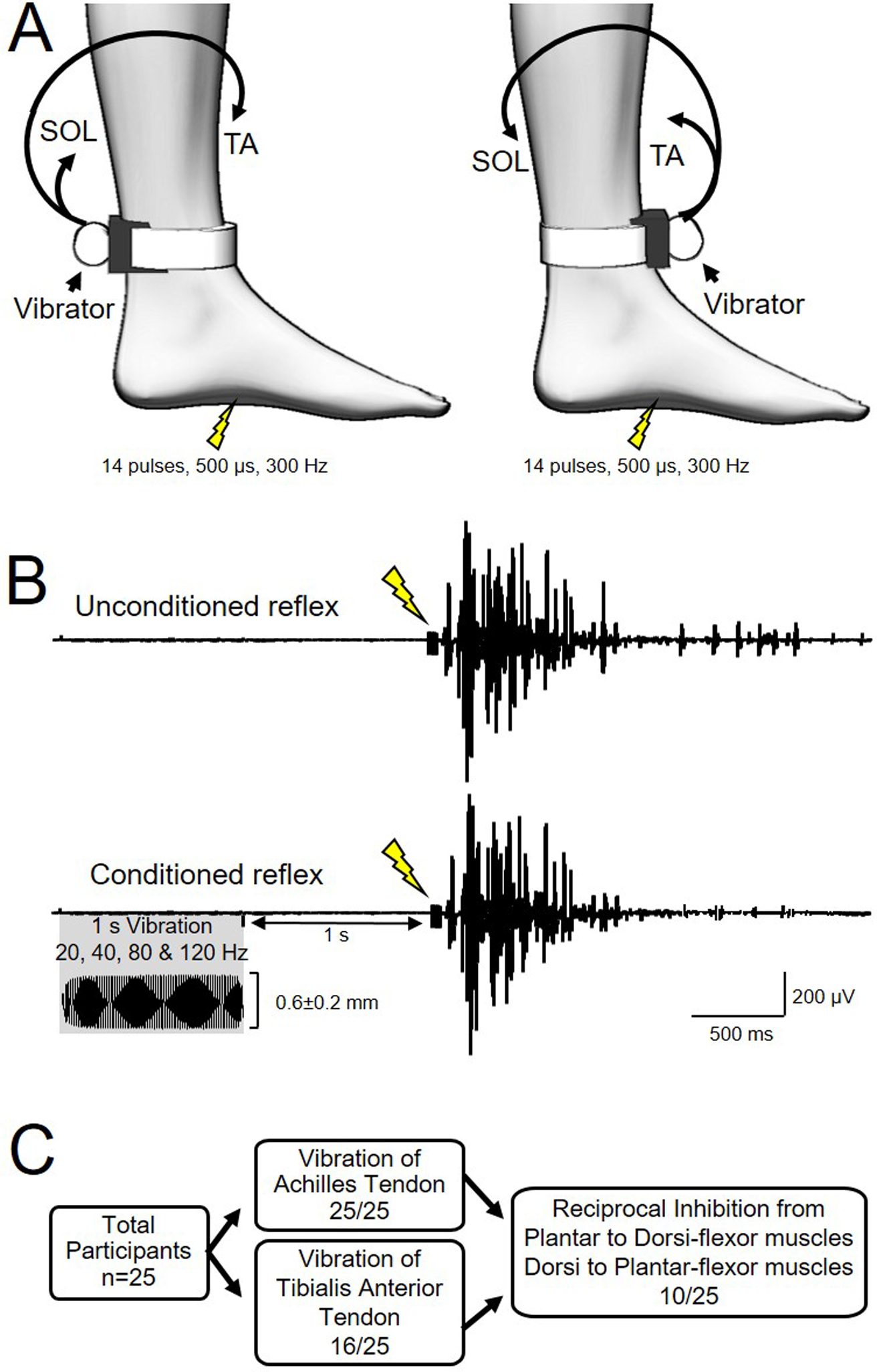

A custom 3D-printed case containing a vibrator motor (320–102; Precision Microdrives, London, UK) was attached over the Achilles or the TA tendon with an elastic strap in such a way that the axis of the vibrator motor was perpendicular to the muscle tendon tested and that the eccentric weight was aligned to the midline of the tendon (Fig. 1A). The strap was adjusted to standardize pressure between the limb and device at ~1N (FlexiForce A401; Tekscan, Inc, South Boston, MA). Real-time vibration acceleration data was acquired with an accelerometer (ADXL377; Adafruit Industries, New York, NY) sampled at 3000 Hz (1401 interface, Signal v6, Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England) to ensure consistent vibration amplitude throughout the different frequencies tested. Achilles and TA tendon vibration were applied at 20, 40, 80, and 120 Hz at similar amplitudes (20 Hz=0.5±0.2 mm, 40 Hz=0.5±0.1 mm, 80 Hz=0.5±0.07 mm, and 120 Hz=0.5±0.04 mm; F3,72=1.5, p=0.2).

Figure 1. Experimental setup.

A) Cutaneous reflexes were evoked by electrical stimulation of the mid arch of the foot (14 pulses, 500μs duration, 300 Hz). The vibrator was attached to the leg over the Achilles tendon or tibialis anterior (TA) tendon at the ankle with the eccentric weight aligned with the tendon and axis of rotation perpendicular to the tendon. Electromyographic (EMG) activity was recorded from the TA and soleus (SOL) muscles. B) Ten unconditioned and 10 conditioned (1s vibration of Achilles or TA tendon ending 1s before electrical stimulation) reflexes were recorded at each vibration frequency (20, 40, 80 and 120 Hz; 0.56±0.17 mm amplitude) for each tendon. C) Number of participants for each part of the study.

Cutaneous Reflex.

During testing, participants were seated with the tested leg placed on a custom platform with the hip (~120°) and knee (~160°) flexed and the ankle restrained by straps in ~110° of plantarflexion. The cutaneous reflex was evoked by electrical stimulation of the medial plantar nerve at the mid-arch of the foot with a bipolar electrode configuration (2 cm diameter Ag/AgCl electrodes; ConMed Corp., Utica, NY; 2 cm distance between electrodes) using a high frequency train of pulses (14 pulses, pulse duration 500 μs, frequency 300 Hz; DS7A stimulator; Digitimer, Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK) and referred as unconditioned reflex (Fig. 1B). Previous studies using electrical stimulation to elicit the cutaneous reflex in lower-limb muscles in humans with SCI have used intensities between 15 and 100 mA (Murray et al., 2010; D’Amico et al., 2013; Butler et al., 2016). Our preliminary data showed that the amplitude and duration of the cutaneous reflex in the TA muscle changed with increases in stimulus intensity (Amplitude: F4,25=9.9, p<0.01; Duration: F4,25=3.0, p=0.04). Thus, we completed an intensity recruitment curve in each SCI participant to determine the intensity at which both components of the cutaneous reflex were present. Consistent with previous results, we found that in all participants on average 50.9±27.0 mA (range=10–100 mA) was needed to elicit the cutaneous reflex and that higher stimulation intensities were needed in participants with motor complete (71.4±23.2 mA) compared with the incomplete (38.8±16.8 mA, p<0.001) injuries. The onset latency and duration of the entire reflex were determined on individual trials and mean values were calculated. Reflex onset and offset were defined as a time point where mean rectified background EMG activity in each of the muscles tested exceeded the baseline by 5SD above the resting EMG background measured 100 ms before the stimulus artifact. To ensure that the magnitude of the reflex was not influenced by variations in reflex duration in each muscle, the mean amplitude was also calculated using a fixed window corresponding to the duration of the unconditioned TA and SOL reflex. We measured the latency, mean amplitude of the long-polysynaptic (LPR, from onset to 500 ms) and the long-lasting (LLR, from 500 to reflex offset) components of the cutaneous reflex (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011; Norton et al., 2008) and the total duration of the reflex. For the LLR, a window from 500 ms post stimulation to the average offset time of the unconditioned reflexes for each participant and muscle was used for analysis. Tendon vibration was applied to the Achilles or TA tendon for 1 s, on separate experiments, ending 1 s prior to the electrical pulses for evoking the cutaneous reflex. Note that overall the cutaneous reflex in the SOL was smaller in amplitude and duration compared with the TA therefore we examined the cutaneous reflex in fewer subjects in the SOL (n=16) compared with the TA (n=25) muscle. The cutaneous reflex was tested without vibration (unconditioned reflex) and with a preceding vibratory stimulus (conditioned reflex) in a randomized order (Fig. 1B). Ten unconditioned and 10 conditioned reflexes were tested at each frequency. The amplitude of cutaneous reflex was normalized to the amplitude of the maximal motor response (M-max). The M-max of the TA and SOL was obtained by using supramaximal electrical stimulation (pulse during 200 μs, DS7A stimulator, Digitimer, Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK) over the common peroneal and posterior tibial nerve, respectively. The stimulus intensity was increased in 10 mA steps until the amplitude of the M-max failed to increase with increases in intensity. A total of 80 reflexes were acquired in each experiment.

Reciprocal Ia inhibition.

Reciprocal Ia inhibition was tested using a previously described paradigm (Capaday et al., 1990) during ~10% of isometric maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) into dorsiflexion and plantarflexion without vibration (unconditioned trials) and with a preceding vibratory stimulus at 80 Hz (conditioned trials) in a randomized order (n=10). Note that this frequency was used because of the strong suppressive effects of vibration at 80 Hz on the LLR. During MVCs, subjects were asked to perform three brief MVCs for 3–5 s with each of the muscles tested, separated by ~30 s of rest. The maximal mean EMG activity measure over a period of 1 s on the rectified response generated during each MVC was analyzed and the highest value of the three trials was used. Visual feedback was provided to participants to unsure that participants maintained ~10% of MVC during testing (dorsiflexion: unconditioned trials=12.0±3.6% of MVC, conditioned trials=12.1±3.9% of MVC; plantarflexion: unconditioned trials=13.9±3.1% of MVC, conditioned trials=13.3±3.0% of MVC; p=0.2). Reciprocal Ia inhibition from plantarflexor to dorsiflexor muscles was assessed by using electrical stimulation (DS7A stimulator; Digitimer, Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK) over the posterior tibial nerve and from dorsiflexor to plantarflexor muscles was assessed by using electrical stimulation over the common peroneal nerve at motor threshold intensity. Motor threshold was defined as the minimal intensity required to elicit a motor response of ≥50 μV in 3 out of 5 trials. Electrical pulses were delivered at 3 s intervals (0.33 Hz). One-hundred unconditioned and 100 conditioned trials were acquired. In conditioned trials, tendon vibration was applied to the Achilles or TA tendon for 1 s, ending 1.5 s prior to the electrical stimulus (corresponding to the time between vibration and the LLR in the reflex experiments) used to test reciprocal Ia inhibition. Data were analyzed by averaging mean rectified EMG activity for each condition. Mean amplitude was calculated for the 90 ms prior to stimulation as the baseline amplitude. Inhibition was identified as the area where mean rectified EMG remained below the baseline amplitude for a minimum of 10 ms. Inhibition area was calculated as:

Inhibition Area was then normalized to the baseline amplitude (Bunday et al., 2014):

Inhibition area was calculated for both the 1st 10ms of inhibition (for between muscle comparisons) and the duration of the unconditioned trial (to examine effects of vibration).

Data analysis.

Normal distribution was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk’s test and homogeneity of variances by the Levene’s test of equality and Mauchly’s test of sphericity. When sphericity could not be assumed, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction statistic was used. Latencies, durations and EMG amplitudes of the unconditioned LLR and LLR were compared between the TA and SOL muscles using Mann-Whitney U tests in all subjects and between participants with motor complete and incomplete injuries. Three-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to examine the effect of VIBRATION (unconditioned reflex, conditioned reflex by vibration at 20, 40, 80, and 120 Hz), COMPONENT (LPR, LLR) and MUSCLE (TA, SOL) on the mean amplitude of the cutaneous reflex when the Achilles and TA tendons were vibrated. One way ANOVA was used to test the effect of stimulation intensity on reflex amplitude and duration during preliminary experiments. Two-way repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare the effect of CONDITION (unconditioned trials, conditioned trials by vibration at 80 Hz) and MUSCLE on the latency, duration, voluntary EMG activity, and magnitude of reciprocal Ia inhibition. A mixed-model repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine the effect of INJURY (motor complete, incomplete), CONDITION and MUSCLE on the mean amplitude of the LLR of the cutaneous reflex. Tukey post hoc analysis was used to test for significant comparisons. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient analysis were used as needed. All statistical analyses were conducted with SigmaPlot (Systat; San Jose, CA). Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. Group data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

Results

Unconditioned reflex

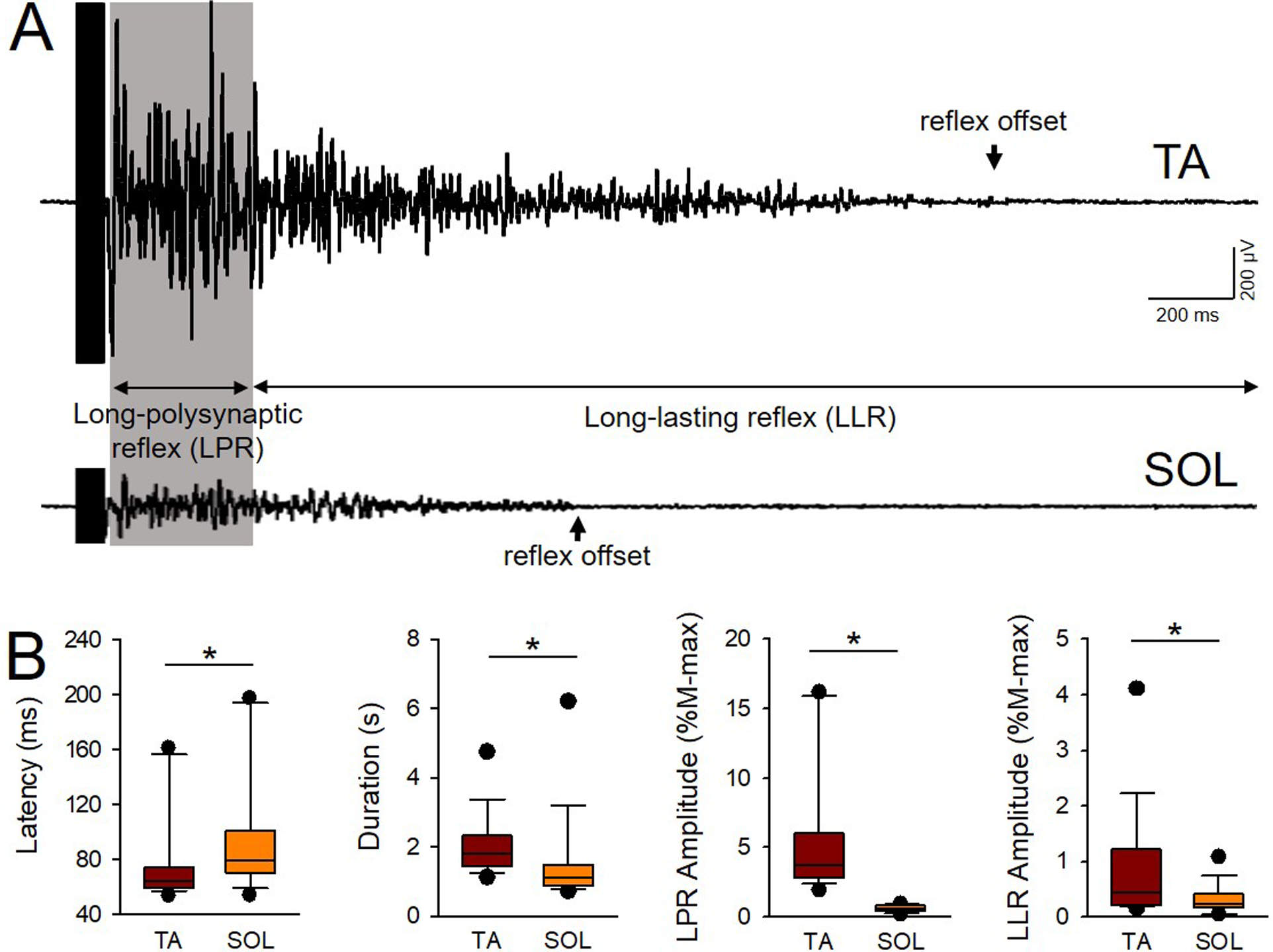

Figure 2A illustrates averaged EMG traces of the unconditioned cutaneous reflex in the TA and SOL muscles in an individual with SCI. Note that the magnitude of the reflex is larger in the TA compared with the SOL muscle. We found that the onset latency of the reflex was shorter in the TA (76.8±32.6 ms) compared with the SOL (96.6±4.1 ms; U=67.0, p=0.02; Fig. 2B) in the majority of participants (15/16). In addition, the total reflex duration was longer in TA (2.0±0.8 s) compared with the SOL (1.4±1.3 s; U=43.0, p<0.01) in the majority of participants (14/16). The amplitude of the LPR and the LLR was larger in the TA (LPR=5.6±4.6% M-max, 86.6±64.3 μV; LLR=0.8±1.0% M-max, 16.7±12.7 μV) compared with the SOL (LPR=0.6±0.2% M-max, 17.2±9.4 μV; U=0.0, p<0.01; LLR=0.3±0.2% M-max, 6.3±5.7 μV; U=590, p=0.01; Fig. 2B) muscle. Note that a larger mean amplitude in the LPR and LLR in the TA compared with the SOL was found in 13/16 participants. The onset latency of the reflex was longer in both muscles in participants with motor complete (TA=90.2±35.6 ms; SOL= 126.0±55.0 ms) compared with incomplete (TA=64.1±8.9 ms, U=32.0, p=0.02; SOL=72.9±9.9ms, U=10.5 p=0.03) injuries. No differences were found on the total reflex duration in participants with motor complete (TA=1.7±0.6 s, SOL=1.9±2.3 s) compared with incomplete (TA=1.7±0.8 s, U=70.0 p=0.8; SOL=1.2±0.4 s, U=31.0, p=1.0) injuries. Also, the amplitude of the LPR and LLR was similar for the TA (p=0.16, p=0.22, respectively) and SOL (p=0.17, p=0.40, respectively) in participants with motor complete and incomplete SCI.

Figure 2. Unconditioned TA and SOL cutaneous reflexes.

A) Averaged EMG traces of the unconditioned cutaneous reflex in the TA (upper trace) and SOL (lower trace) muscles in an individual with SCI (Participant #7 on Table 1: C5, AIS C, Female, 20 yrs, 2 yrs post-SCI). Note that the magnitude of the reflex is larger in the TA compared with the SOL muscle. The latency and total duration of each reflex were calculated as well as the amplitude of the long-polysynaptic (LPR, gray shadow) and long-lasting (LLR) component of the cutaneous reflex. Arrows signify the time of reflex offset for each muscle. B) Graphs show group data for latency, duration, and amplitude of the LPR and LLR in the TA and SOL muscles (n=16). The abscissa shows the muscle tested (TA and SOL). The ordinate shows the latency in milliseconds (ms), and the amplitude of the LPR and LLR expressed as a % of the M-max of each muscle (M-max*s). Note that the latency was longer in the SOL compared with the TA muscle, and total reflex duration was prolonged in the TA compared with the SOL muscle. Both LPR and LLR amplitude were larger in the TA compared with the SOL muscle. Error bars represent the 25th and 75th percentile.*p<0.05.

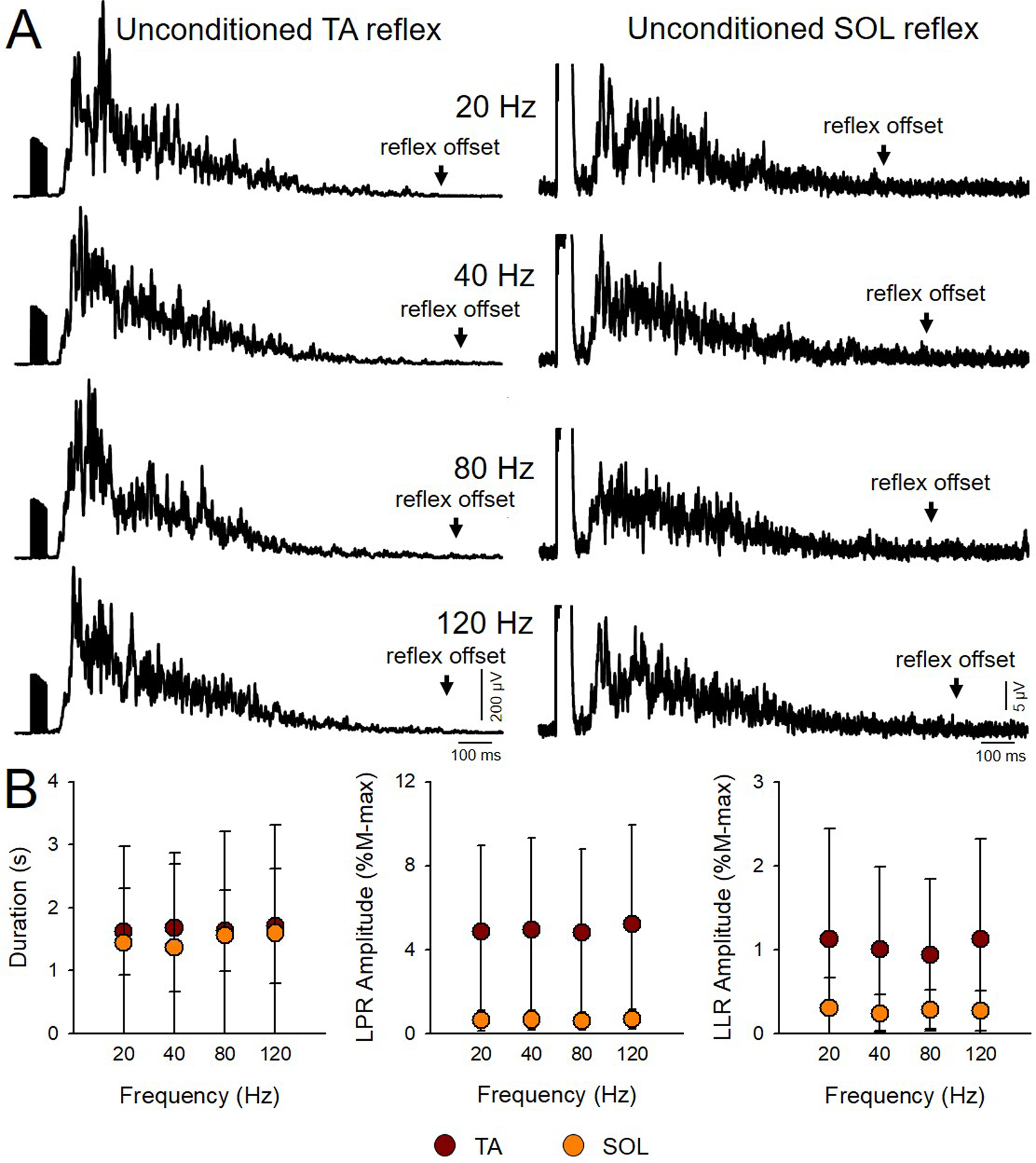

Figure 3A illustrates averaged rectified EMG traces of the unconditioned cutaneous reflex in the TA (left panel) and SOL (right panel) muscle in a representative SCI participant. We tested 10 unconditioned reflexes in a randomized order at each vibration frequency. We found that the total duration of the unconditioned TA (F3,72=0.16, p=0.9) and SOL (F3,45=1.0, p=0.4) reflex remained constant across trials (Fig. 3B, left side graph). In addition, we found that the amplitude of the LPR (TA: F3,72=1.4 p=0.3; SOL: F3,45=0.8, p=0.5; Fig. 3B middle graph) and LLR (TA: F3,72=1.1, p=0.4; SOL: F3,45=0.5, p=0.7; Fig. 3B right side graph) were similar across trials.

Figure 3. Unconditioned TA and SOL cutaneous reflexes at each frequency.

A) Averaged rectified EMG traces of the unconditioned cutaneous reflex in the TA (left panel) and SOL (right panel) muscles in a representative SCI participant (Participant #15 on Table 1: T4, AIS A, Male, 58 yrs, 3 yrs post-SCI). We tested 10 unconditioned reflexes in a randomized order with 10 conditioned reflexes by vibration at different frequencies. B) Graphs show group data for the duration and of the LPR and LLR for the TA (brown; n=16) and SOL (orange; n=16) unconditioned reflexes. The abscissa shows the unconditioned reflexes tested at each frequency. The ordinate shows the duration in seconds (s), and the amplitude of the LPR and LLR expressed as a % of the M-max (M-max*s). Note that duration and amplitude of the LPR and LLR unconditioned reflexes remain similar across frequencies in both muscles. Error bars represent standard deviation.*p<0.05.

Effects of vibration on the cutaneous reflex

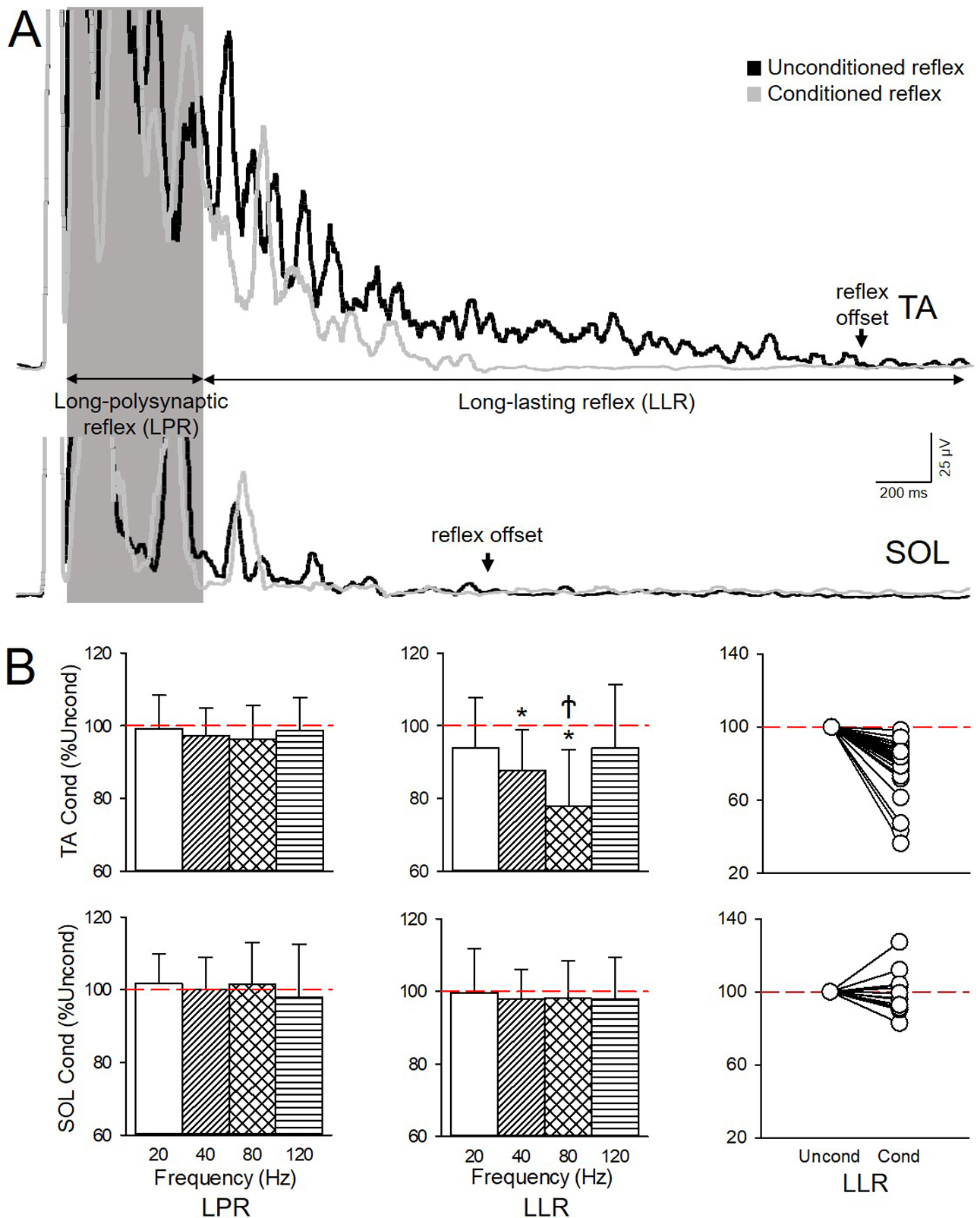

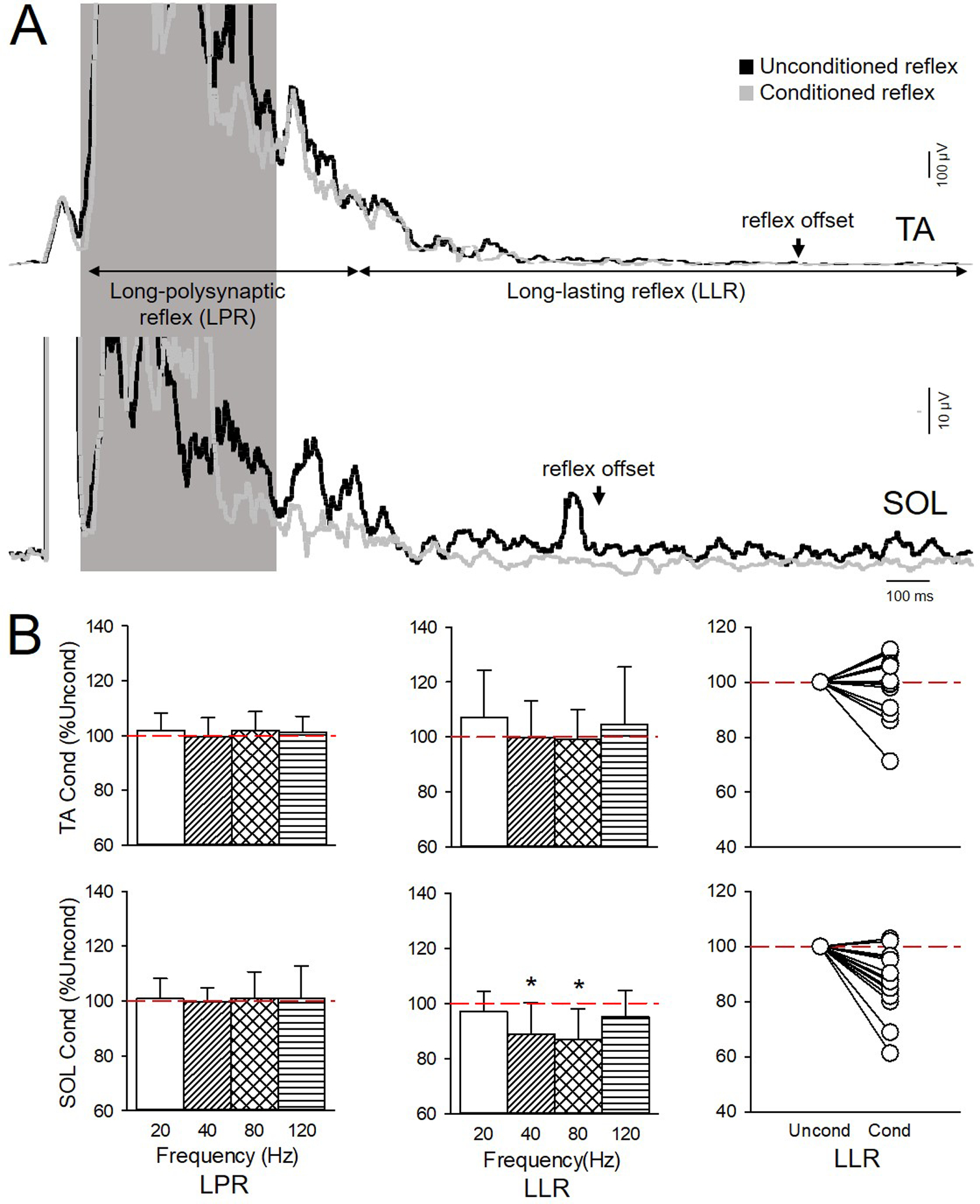

Figure 4A illustrates representative averaged rectified and smoothed EMG traces of the conditioned (gray traces) and unconditioned (black traces) cutaneous reflexes in the TA (upper traces) and SOL (lower traces) muscle when the Achilles tendon was vibrated at 80 Hz in a representative individual with SCI. Note here that the amplitude of the LLR was reduced in the TA but not in the SOL in the conditioned compared with the unconditioned reflex. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA showed an effect of Achilles tendon VIBRATION (F4,60=2.7, p=0.04), COMPONENT (F1,15=24.9, p<0.01), MUSCLE (F1,15=23.2, p<0.01) and their interaction (F4,60=2.8, p=0.03) on the cutaneous reflex. We also found an interaction between VIBRATION × COMPONENT (F4,60=3.8, p<0.01), MUSCLE × VIBRATION (F4,60=4.9, p<0.01), and MUSCLE × COMPONENT (F1,15=12.7, p<0.01). Post hoc analysis revealed that Achilles tendon vibration at 40 (87.6±11.3% of the unconditioned reflex; p<0.01) and 80 Hz (77.7±15.6% of the unconditioned reflex; p<0.01), but not at 20 (94.0±13.7% of the unconditioned reflex; p=0.8) and 120 Hz (94.0±17.4% of the unconditioned reflex; p=1.0), reduced the amplitude of the LLR in the TA (Fig. 4B, upper middle graph). The LLR was reduced by at least 10% at 40 (16/25; range: 6% increase to 38% decrease) and 80 Hz (22/25; range: 2% to 64% decrease; Fig. 4B, upper right side graph) in the majority of SCI participants. Note that the amplitude of the LLR was reduced to a larger extent at 80 compared with 40 Hz (p<0.01). In contrast, Achilles tendon vibration did not affect the LLR mean in the SOL muscle at any of the frequencies tested (20 Hz=99.7±12.0% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; 40 Hz=97.8±8.2% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; 80 Hz=98.0±10.5% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; 120 Hz=97.9±11.4% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; Fig. 4B, lower middle graph). In addition, Achilles tendon vibration at any frequency did not affect the LPR in the TA (p=1.0) and SOL (p=1.0) muscle.

Figure 4. Effects of Achilles tendon vibration on the cutaneous reflex.

A) Averaged rectified and smoothed EMG traces of the conditioned (gray traces) and unconditioned (black traces) cutaneous reflexes in the TA (upper traces) and SOL (lower traces) muscle when the Achilles tendon was vibrated at 80 Hz in an individual with SCI (Participant #4 on Table 1: C4, AIS D, Female, 21 yrs, 3 yrs post-SCI). B) Graphs show group data showing the amplitude of the LPR and LLR after Achilles tendon vibration at 20, 40, 80 and 120 Hz in TA (upper graphs; n=25) and SOL (lower graphs; n=16). The abscissa shows the vibration frequency (20 Hz=white bars, 40 Hz=diagonal bars, 80 Hz=crossed bars, and 120 Hz= horizontal bars). The ordinate shows the amplitude of the conditioned (Cond) LPR and LLR expressed as a % of the unconditioned (Uncond) reflex (red dashed lines) for each muscle. Right side graphs show individual data for the LLR in both muscles after 80 Hz vibration. Note that LLR was reduced with 40 and 80Hz vibration in TA, but not in SOL, and LPR in both muscles remained unchanged by vibration at all frequencies. Note that the majority of participants had a reduction of the LLR after 80 Hz vibration in the TA but not in the SOL muscle. Error bars represent standard deviation.*p<0.05 vs unconditioned; Ϯp<0.05 vs all other frequencies of vibration.

Figure 5A illustrates representative averaged rectified and smoothed EMG traces of the conditioned (gray traces) and unconditioned (black traces) cutaneous reflex in both muscles when the TA tendon was vibrated at 80 Hz in an individual with SCI. Note here that the amplitude of the LLR was reduced in the SOL but not in the TA muscle in the conditioned compared with the unconditioned reflex. Three-way repeated measures ANOVA showed an effect of TA tendon VIBRATION (F4,60=3.3, p=0.02), COMPONENT (F1,15=24.9, p<0.01), MUSCLE (F1,15=13.1, p<0.01) but not in their interaction (F4,60=1.9, p=0.1) on the cutaneous reflex. We found an interaction between VIBRATION × COMPONENT (F4,60=5.2, p<0.01) and MUSCLE × COMPONENT (F1,15=15.7, p<0.01). Post hoc analysis revealed that TA tendon vibration at 40 (88.8±11.3% of the unconditioned reflex, p=0.03) and 80 Hz (86.9±10.9% of the unconditioned reflex, p=0.01), but not at 20 (97.0±7.4% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0) and 120 Hz (95.2±9.5% of the unconditioned reflex, p=0.9) reduced the LLR in TA (Fig. 5B, lower middle graph). The LLR was reduced by at least 10% at 40 (7/16; range: 5% increase to 40% decrease) and 80 Hz (11/16; range; 2% increase to 39% decrease; Fig. 4B, lower right side graph) in the majority of SCI participants. No differences were found in amplitude of the LLR at 40 and 80 Hz (p=1.0). In contrast, TA tendon vibration did not affect the LLR in the TA muscle at any of the frequencies tested (20 Hz=107.2±17.2% of the unconditioned reflex, p=0.9; 40 Hz=99.8±13.3% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; 80 Hz=99.1±10.9% of the unconditioned reflex, p=1.0; 120 Hz=104.6±20.8% of the unconditioned reflex, p=0.7; Fig. 5B, upper middle graph). TA tendon vibration at any frequency did not affect the amplitude of the LPR reflex in the TA (p=1.0) and SOL (p=1.0) muscle. Additional analysis revealed an effect of CONDITION (F1,14=17.0, p<0.01), and MUSCLE (F1,14=10.3, p<0.01) but not INJURY (F1,14=2.1, p=0.17) nor in their interaction (F1,14=0.16, p=0.69) on the LLR of the cutaneous reflex.

Figure 5. Effect of TA tendon vibration on the cutaneous reflex.

A) Averaged rectified and smoothed EMG traces of the conditioned (gray traces) and unconditioned (black traces) cutaneous reflexes in the TA (upper traces) and SOL (lower traces) muscle when the TA tendon was vibrated at 80 Hz in an individual with SCI (Participant #18 on Table 1: T5, AIS A, Male, 46 yrs, 18 yrs post-SCI). B) Graphs show group data showing LPR and LLR after TA tendon vibration at 20, 40, 80 and 120 Hz in TA (upper graphs; n=25) and SOL (lower graphs; n=16). The abscissa shows the vibration frequency (20 Hz=white bars, 40 Hz=diagonal bars, 80 Hz=crossed bars, and 120 Hz= horizontal bars). The ordinate shows the amplitude of the conditioned (Cond) LPR and LLR expressed as a % of the unconditioned (Uncond) reflex (red dashed lines) for each muscle. Right side graphs show individual data for the LLR in both muscle after 80 Hz vibration. Note that LLR was reduced with 40 and 80 Hz vibration in SOL, but not in TA, and LPR in both muscles was unchanged. Error bars represent standard deviation.*p<0.05 vs unconditioned.

Reciprocal Ia inhibition

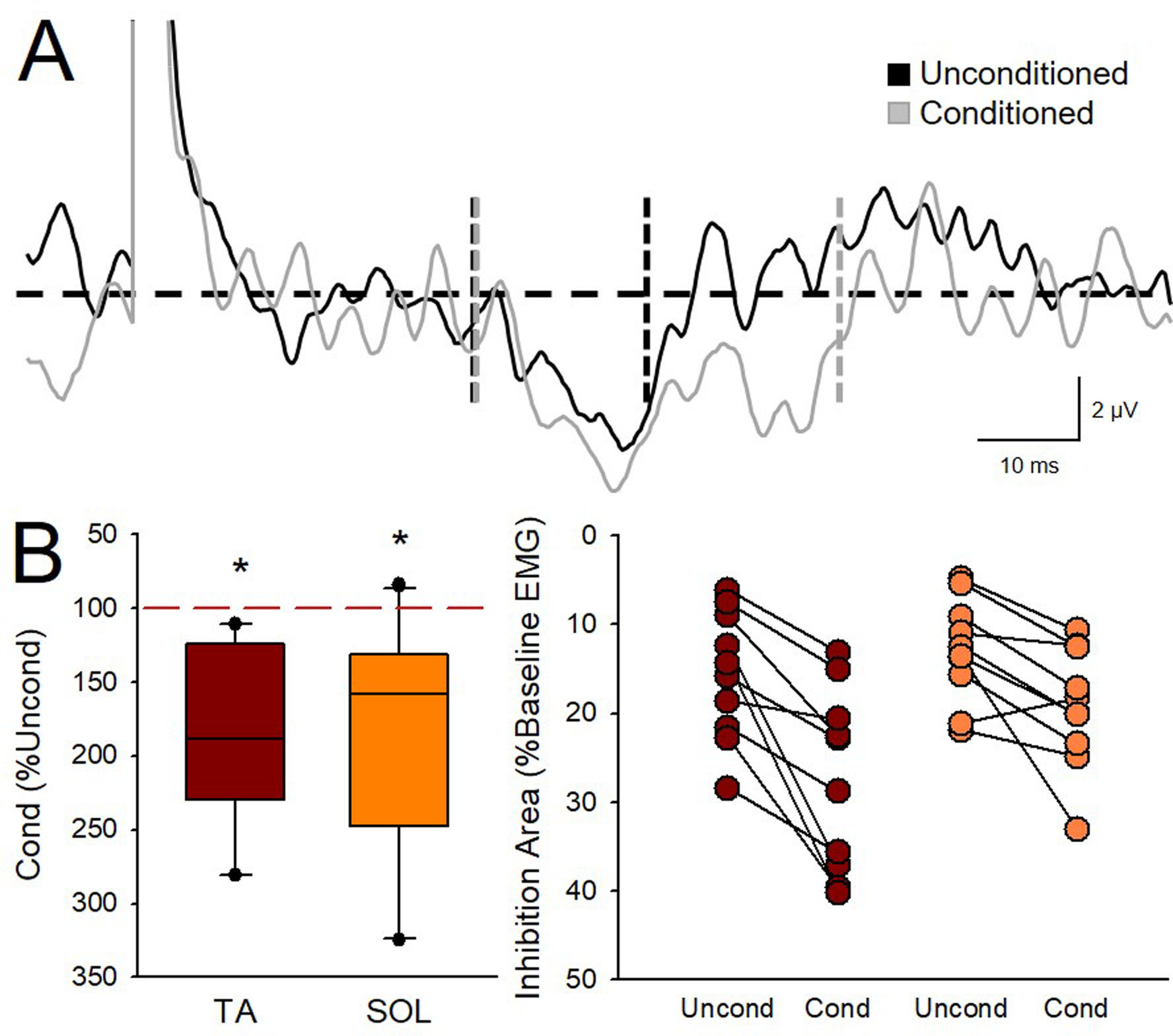

Averaged rectified EMG activity recorded from the TA muscle during 10% of MVC with (gray trace) and without (black trace) preceding vibration of the Achilles tendon at 80 Hz (Fig. 6A). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed an effect of CONDITION (F1,9=16.8, p<0.01), MUSCLE (F1,9=5.8, p=0.04) but not in their interaction (F1,9=1.2, p=0.3) on the duration of reciprocal Ia inhibition. Post hoc analysis showed that the duration of reciprocal Ia inhibition was longer in the TA (unconditioned=19.0±13.0 ms, conditioned=29.7±15.2; p<0.01) and SOL (unconditioned=12.7±6.7 ms, conditioned=19.4±15.6 ms; p<0.01) muscle on trials with (conditioned) compared with without (unconditioned) preceding vibration. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed an effect of CONDITION (F1,9=43.4, p<0.01), MUSCLE (F1,9=5.9, p=0.04) but not in their interaction (F1,9=2.9, p=0.1) on the magnitude of reciprocal Ia inhibition. Post hoc analysis showed that Achilles tendon vibration at 80 Hz increased reciprocal Ia inhibition in the TA (unconditioned=15.5±6.7%, conditioned= 24.2±7.9%; p<0.01; Fig. 6B, right graph) in all SCI participants (10/10). Similarly, TA tendon vibration at 80 Hz increased reciprocal Ia inhibition in the SOL (unconditioned=10.9±6.0%, conditioned= 16.4±4.7%; p<0.01; Fig. 6B) in the majority of SCI participants (9/10). Note that at baseline (unconditioned trials) reciprocal Ia inhibition was greater in the TA compared with the SOL (p=0.02; Fig. 6B, left graph). Note that similar results were found with the same window was used for analysis across muscles (CONDITION: F1,9=31.0, p<0.01, MUSCLE: F1,9=8.2, p=0. 02, interaction F1,9=3.5, p=0.1).

Figure 6. Effect of vibration on reciprocal Ia inhibition.

A) Averaged rectified EMG activity recorded from the TA muscle during 10% of MVC with and without preceding vibration of the Achilles tendon at 80 Hz. The black horizontal dashed line represents the mean baseline EMG amplitude. Vertical dashed lines represent the onset and offset of inhibition for the Unconditioned (Uncond, black trace) and Conditioned (Cond, grey trace). Note that both the amplitude and duration of the inhibition was increased with 80 Hz Achilles tendon vibration. B) Group data showing reciprocal Ia inhibition in the TA (red) and SOL (orange) muscle after 80 Hz vibration of the Achilles and TA tendon, respectively (left graph; n=10). The abscissa shows the muscle tested (TA and SOL). The ordinate shows the area of inhibition in conditioned trials expressed as a % of the inhibition found in unconditioned trials for each muscle. Error bars represent the 25th and 75th percentiles. Individual data for the area of inhibition in the unconditioned and conditioned trials for each muscle are presented on the right (n=10). The abscissa shows the conditions tested [Unconditioned (Uncond) and 80 Hz vibration conditioned (Cond) trials in the TA (brown) and SOL (orange) muscles]. The ordinate shows the inhibition area as a percentage of the mean baseline EMG amplitude for each muscle and condition. Note that inhibition increased in the TA in all participants and in 9 out of 10 participants in the SOL. *p<0.05.

Correlations

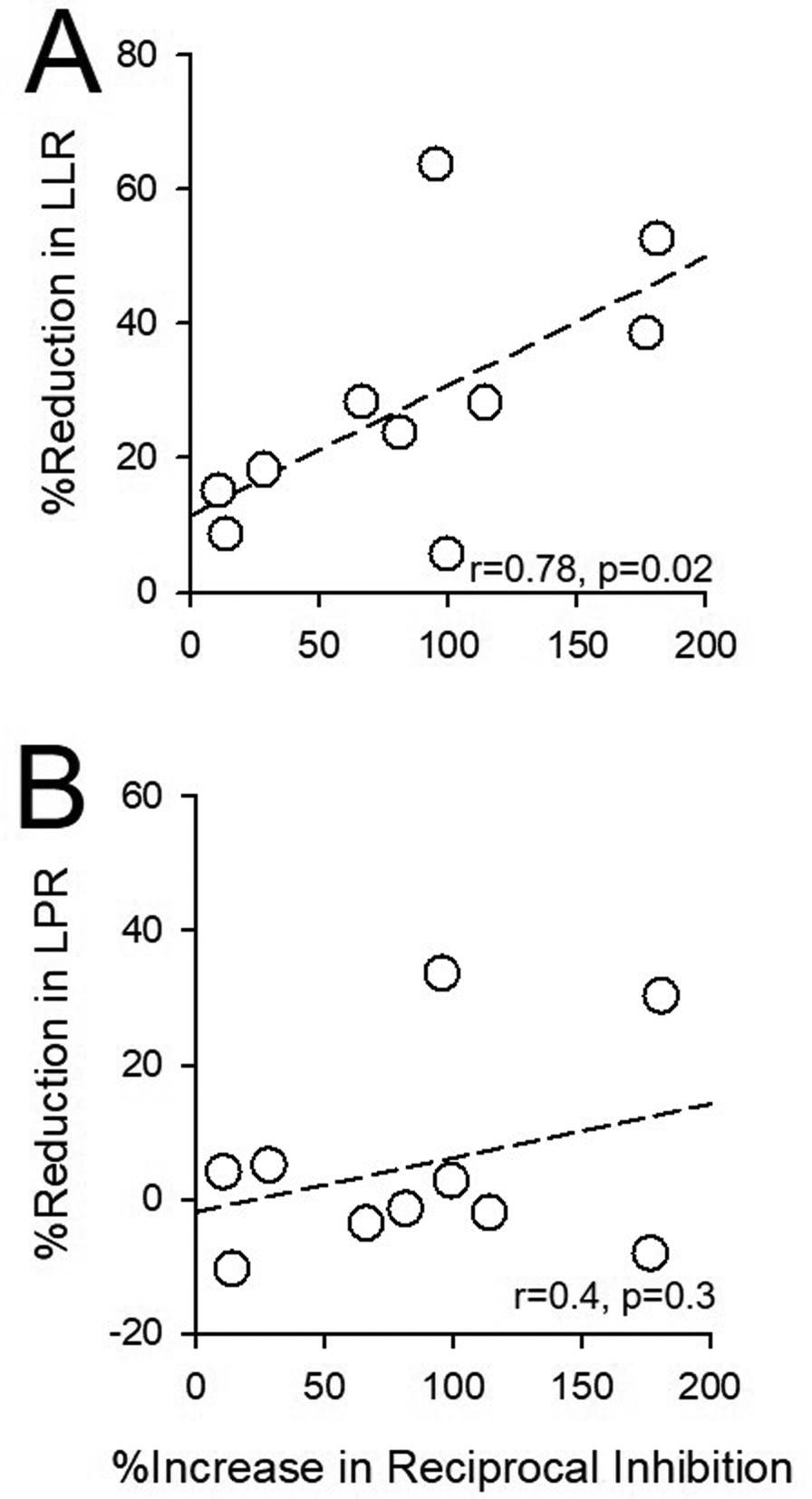

The latency of the TA reflex was correlated with the latency of the SOL reflex (r=0.7, p=0.01). Thus, individuals with prolonged TA reflexes also showed prolonged SOL reflexes. The LPR in the TA was correlated with the LPR in the SOL (r=0.5, p=0.04). However, the LLR was not correlated between muscles (r=0.2, p=0.4). The spasm frequency was correlated with the reflex duration in both TA (ρ=0.5; p=0.05) and SOL (ρ=0.6; p<0.01) muscles. Notably, the increases in reciprocal Ia inhibition by vibration were correlated with the reduction of LLR in the TA muscle (r=0.78, p=0.02; Fig. 6C), but not the LPR (r=0.4, p=0.3), induced by vibration. This association was only examined in the TA muscle because only five of the participants who were able to complete the reciprocal Ia inhibition experiment had cutaneous reflex activity in the SOL muscle. None of the reflex variables correlated with the time post injury (TA duration: p=0.1; SOL duration: p=0.4; TA LPR: p=0.6; TA LLR: p=0.5; SOL LPR: p=0.7; SOL LLR: p=0.6), injury level (TA duration: p=0.3; SOL duration: p=0.5; TA LPR: p=0.6; TA LLR: p=0.4; SOL LPR: p=0.5; SOL LLR: p=0.5) or the degree of spasticity (TA duration: p=1.0; SOL duration: p=0.8; TA LPR: p=1.0; TA LLR: p=1.0; SOL LPR: p=0.7; SOL LLR: p=0.6). Whether participants were taking anti-spastic medication also did not have an effect on the reflex (TA duration: p=0.7; SOL duration: p=0.9; TA LPR: p=0.2, TA LLR: p=0.5, SOL LPR: p=0.3, SOL LLR p=0.7). The reduction in the LLR evoked by vibration (TA LLR: r=0.0, p=1.0; SOL LLR: r=0.15, p=0.6) was not correlated with MAS scores in the SOL and TA muscle, respectively.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that tendon vibration suppresses late cutaneous reflex activity in an antagonist but not an agonist ankle muscle in humans with chronic SCI. We studied the effect of vibration on early (LPR) and late (LLR) components of the cutaneous reflex, which reflect to a different extent activity in neuronal pathways contributing to muscle spasms (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011). Specifically, we found that Achilles tendon vibration at 40 and 80 Hz reduced the amplitude of the LLR in the TA but not in the SOL muscle without affecting the LPR. Similarly, tibialis anterior tendon vibration at 40 and 80 Hz reduced the amplitude of the LLR in the SOL but not in the TA muscle without affecting the LPR. Tendon vibration to the Achilles and TA tendon increased reciprocal Ia inhibition between antagonist muscles. Notably, the magnitude of vibratory-induced increases in reciprocal Ia inhibition was correlated with the magnitude of LLR reduction, suggesting that participants with a larger suppression of late cutaneous reflex activity had stronger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonistic muscle. These finding support the hypothesis that tendon vibration attenuates late spasm-like activity in antagonist muscles via reciprocal inhibitory mechanisms following chronic SCI.

Effects of vibration on the cutaneous reflex

Evidence showed that cutaneous reflexes are amplified after SCI (Bennett et al., 2004; Rank et al., 2011; Butler et al., 2016). Here, we found that medial plantar nerve stimulation evoked a cutaneous reflex in the TA and SOL muscles but the duration and amplitude of the reflex was larger in the TA compared with the SOL muscle in humans with chronic SCI. This is consistent with evidence showing that muscle spasms are observed in both flexor and extensor muscles after chronic SCI (Little et al., 1989; Schmit and Benz, 2002). This might also not be surprising since the cutaneous reflex tested in our study involves a flexor withdrawal response, which activate strongly flexor compared with extensor muscles. The main question that we addressed in our study was how to suppress the later part of the cutaneous reflex or spasm-like activity in humans with chronic SCI. Evidence showed that the amplitude of the LPR component of the cutaneous reflex likely reflects the prolonged EPSP and Ca2+ PICs (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011) while the LLR component is likely to be mediated entirely by Ca2+ PICs (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011). Notably, we found that Achilles tendon vibration at 40 and 80 Hz, but not 20 and 120 Hz, reduced the amplitude of the LLR in the antagonist but not in the agonist muscle without affecting the amplitude of the LPR. Similar results were found in the antagonistic SOL muscle when the tibialis anterior tendon was vibrated at 40 and 80 Hz. Our selective effects of tendon vibration in the LLR but not the LPR components of the reflex supports the hypothesis that tendon vibration attenuates spasm-like activity after chronic SCI. This is also consistent with evidence showing attenuation of cutaneous reflexes in various muscles via tendon vibration in people with (Butler et al., 2006) and without (Martin et al., 1990) SCI, suggesting that repeated activation of sensory afferents projecting to motoneurons can be used to modulate symptoms of hyperexcitability. Our results indicate that 80 Hz is the optimal frequency for suppressing the LLR in the antagonistic muscle. Muscle spindle primary endings are sensitive to low-amplitude mechanical vibrations applied to the tendons as the one used in our study (Roll et al., 1989). Note that muscle spindle primary endings (Ia fibers) fire with a one-to-one ratio up to what appears to be an optimal frequency of 80 Hz but can respond to vibration up to ~200 Hz (Burke et al., 1976; Roll et al., 1989). This might contribute to the strongest effects that we observed at the 80 Hz frequency. Vibratory frequencies around 80 Hz appear to be optimal for facilitation of motor evoked potentials (MEPs) elicited by transcranial magnetic stimulation (Siggelkow et al., 1999; Steyvers et al., 2003) and for suppressing the Soleus H-reflex (Seo et al., 2018) in control subjects. There are factors that may explain the lack of effectiveness of 20 and 120 Hz vibration frequencies. Vibration can activate Ia fibers at a frequency that makes them unresponsive to other inputs, this is a phenomenon known as “busy-line” (Bove et al., 2003). While this could happen at 120 Hz the lack of changes at 20 Hz might be better explained by the fact that this stimulus frequency might be less adequate for the response of the majority of the primary endings. In fact, evidence showed that the secondary endings and Golgi tendon receptors better responded one-to-one at frequencies ~20 Hz (Roll et al., 1989).

A mechanism for LLR suppression

Vibration of a muscle or tendon can inhibit antagonist motoneuron firing (MacDonell et al., 2010) and generate inhibitory post-synaptic potentials in antagonist motoneurons via Ia interneurons (Heckman & Binder, 1991). Note that PICs are sensitive to reciprocal Ia inhibition (Kuo et al., 2003; Hyngstrom et al., 2007; Johnson & Heckman, 2010) and are a primary contributor to the LLR after SCI (Li et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2011). Therefore, it might be possible that vibration, which is known to activate Ia afferents (Roll et al., 1989) would also suppress PICs, which are particularly sensitive to Ia reciprocal inhibition (Kuo et al., 2003; Hyngstrom et al. 2007; Johnson & Heckman, 2010). This is consistent with our finding that tendon vibration at 80 Hz increased reciprocal Ia inhibition between antagonistic ankle muscles. We also found that the magnitude of vibratory-induced increases in reciprocal Ia inhibition and decreases in LLR were correlated, suggesting that participants with a larger suppression of late cutaneous reflex activity had stronger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonistic muscle, further supporting our interpretation. This is also consistent with evidence showing that in control subjects (Ritzmann et al., 2018) and in people with incomplete chronic SCI (Perez et al., 2004), whole body and focal tendon vibration increases reciprocal Ia inhibition in an antagonistic muscle. Prolonged activation of Ia interneurons may be due to repetitive firing of Ia afferents due to PICs (Russo & Hounsgaard, 1994, 1996) or potentially PICs generated in the inhibitory interneurons themselves. PICs have also been observed in other types of interneurons (Tepper et al., 2010; Pressler & Regehr, 2013). Recent evidence showed that sensory activation of V3 interneurons can evoke spasms (Lin et al., 2019). Thus, it is also possible that vibration-related activation of Ia and other interneurons involved in the CPG network might contribute to the LLR suppressive effects and needs further investigation. We found that the suppressive effects of vibration on the LLR were more pronounced in the TA with Achilles tendon vibration than in the SOL with TA tendon vibration. This difference might be explained by the fact that in human reciprocal Ia inhibition seems to be stronger from plantarflexor to dorsiflexor than from dorsiflexor to plantarflexor muscles (Crone et al., 1987). This is also supported by our data showing that baseline levels of reciprocal Ia inhibition without vibration were stronger from plantarflexor to dorsiflexor than from dorsiflexor to plantarflexor muscles.

Limitations

It is important to note that we tested individuals with both motor complete (AIS A/B) and incomplete (AIS C/D) SCI. Because the cutaneous reflex is influenced by contributions from afferent input and supraspinal pathways (Pierrot-Deseilligny & Burke 2005), it is possible that differences in connectivity on residual pathways contributed to our findings. Our analyses revealed no differences in the amplitude of the unconditioned and conditioned LLR in the TA and SOL muscles between participants with motor complete or incomplete SCI, suggesting that it is less likely that differences in the preservation of residual pathways affected our results. However, we have to consider that most individuals with a diagnosis of clinically motor complete SCI show evidence for continuity of CNS tissue across the injured segments (Kakulas, 1988; Bunge et al., 1993). In particular, people with motor complete injuries with spasticity show descending connectivity compared with people without spasticity (Sangari et al., 2019). As in other studies (Baunsgaard et al., 2016; Craven & Morris 2010), we found that most of our participants with motor complete injuries presented spasticity in plantarflexor but not in dorsiflexor muscles. If descending connectivity is present in plantarflexor muscles, this might contribute to reciprocal inhibitory effects onto dorsiflexors muscles and explain, at least in part, why vibratory effects were more pronounced when the Achilles compared with the TA tendon was vibrated in people with motor complete injuries. However, we acknowledge that we examined reciprocal Ia inhibition during voluntary activity only in individuals with incomplete injuries and we speculate that the same mechanism is responsible for the attenuation of the LLR in individuals with motor complete injuries.

Functional considerations

Muscle spasms are experienced in ~80% of people with SCI (Little et al., 1989). Spasms commonly interfere with daily activities and are considered to be problematic in the majority of people who experience them (Little et al., 1989; Skold et al., 1999). Care must be taken, when defining spasms and spasticity. Self-reported questionnaires and clinical exams indicate that symptoms of spasticity are characterized by involuntary muscle activity or ‘muscle spasms’, hyperreflexia, and clonus (Dietz, 2000; Nielsen et al., 2007). The definition of spasticity has been broadened and challenged over the years, opening the consideration of including symptoms of upper motor neuron lesion when referring to spasticity which go beyond the classical velocity-dependent presentation (Pandyan et al., 2005). Pharmaceutical agents are considered to be the gold standard treatment for spasticity and spasms following SCI. However, many people find these medications ineffective and/or dislike their side effects, which might interfere with motor function (Adams & Hicks, 2005; McKay et al., 2018; Theriault et al., 2018). Higher use of prescription drugs for spasticity-related problems have also been associated with a greater risk of mortality (Krause et al., 2009); highlighting the need for effective non-pharmacological treatments. Although some studies have suggested that whole body vibration (Ness & Field-Fote, 2009; Estes et al., 2018) and focal vibration (Laessoe et al., 2004; Murillo et al., 2011) can decrease symptoms of spasticity, there is currently no conclusive evidence for their use as an anti-spasmodic approach in people with SCI (Sadeghi & Sawatzky, 2014). Their effect is also short lasting and it seems to be present in participants with severe spasticity (Estes et al., 2018). Because movement‐related receptive fields of motoneurons are widened after SCI (Hyngstrom et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2013) a better control of afferent transmission could result in better management of whole limb spasms after the injury. Our results indicate that focal tendon vibration acting in part through reciprocal inhibitory mechanisms reduced spasm-like activity in an antagonist but not agonist muscle. The correlation found between the duration of reflexes in the TA and SOL muscles and the self-reported spasm frequency, suggest that these outcomes might have clinical relevance. Thus, focal vibration targeting antagonist tendons may provide a viable alternative as it avoids the side effects of whole body vibration (Wysocki et al., 2011) and can be applied in multiple environments and during daily life activities.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7. Correlations.

Graphs show correlations between increases in reciprocal Ia inhibition and reduction of LLR (A) and LPR (B) in the TA muscle after 80 Hz Achilles tendon vibration. The abscissa shows the increase in the area of inhibition in conditioned trials expressed as a % of the inhibition found in unconditioned trials for the TA. The ordinate shows the reduction in amplitude of the conditioned LPR and LLR expressed as a % of the unconditioned reflex. Note that participants with a larger suppression of later cutaneous reflex activity had stronger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonistic muscle. Pearson correlation coefficients and p-values are displayed in the lower right corner of each graph.

Key points.

Cutaneous reflexes were tested to examine the neuronal mechanisms contributing to muscle spasms in humans with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI). Specifically, we tested the effect of Achilles and tibialis anterior tendon vibration on the early and late components of the cutaneous reflex and reciprocal Ia inhibition in the soleus and tibialis anterior muscles in humans with chronic SCI.

We found that tendon vibration reduced the amplitude of later but not earlier cutaneous reflex activity in the antagonist but not agonist muscle relative to the location of the vibration. In addition, reciprocal Ia inhibition between antagonist ankle muscles increased with tendon vibration and participants with a larger suppression of later cutaneous reflex activity had stronger reciprocal Ia inhibition from the antagonistic muscle.

Our study is the first to provide evidence that tendon vibration attenuates late cutaneous spasm-like reflex activity likely via reciprocal inhibitory mechanisms, and may represent a method, when properly targeted, for controlling spasms in humans with SCI.

References

- Adams MM & Hicks AL. (2005) Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 43(10), 1362–4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baunsgaard CB, Nissen UV, Christensen KB & Biering-Sorensen F. (2016). Modified Ashworth scale and spasm frequency score in spinal cord injury: reliability and correlation. Spinal Cord 54(9), 702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Li Y, Harvey PJ & Gorassini M. (2001). Evidence for plateau potentials in tail motoneurons of awake chronic spinal rats with spasticity. J Neurophysiol 86(4), 1972–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DJ, Sanelli L, Cooke CL, Harvey PJ & Gorassini MA. (2004). Spastic long-lasting reflexes in the awake rat after sacral spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 91(5), 2247–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW & Smith MB. (1987). Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys Ther 67(2), 206–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove M, Nardone A & Schieppati M. (2003). Effects of leg muscle tendon vibration on group Ia and group II reflex responses to stance perturbation in humans. J Physiol 550(2), 617–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunday KL, Tazoe T, Rothwell JC & Perez MA. (2014). Subcortical control of precision grip after human spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 34(21), 7341–7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge RP, Puckett WR, Becerra JL, Marcillo A & Quencer RM. (1993). Observations on the pathology of human spinal cord injury. A review and classification of 22 new cases with details from a case of chronic cord compression with extensive focal demyelination. Adv Neurol 59, 75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke D, Hagbarth KE, Lofstedt L & Wallin BG. (1976). The responses of human muscle spindle endings to vibration of non-contracting muscles. J Physiol 261(3), 673–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JE, Godfrey S & Thomas CK. (2006). Depression of involuntary activity in muscles paralyzed by spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve 33(5), 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Cody FW & Stein RB. (1990). Reciprocal inhibition of soleus motor output in humans during walking and voluntary tonic activity. J Neurophysiol 64(2), 607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven BC & Morris AR. (2010). Modified Ashworth scale reliability for measurement of lower extremity spasticity among patients with SCI. Spinal Cord 48(3), 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone C, Hultborn H, Jespersen B & Nielsen J. (1987). Reciprocal Ia inhibition between ankle flexors and extensors in man. J Physiol 389, 163–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico JM, Murray KC, Li Y, Chan KM, Finlay MG, Bennett DJ & Gorassini MA. (2013). Constitutively active 5-HT2/α1 receptors facilitate muscle spasms after human spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 109(6), 1473–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico JM, Condliffe EG, Martins KJ, Bennett DJ & Gorassini MA. (2014). Recovery of neuronal and network excitability after spinal cord injury and implications for spasticity. Front Integr Neurosci 8, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo ER, Maria RM, Alonso KC & Cliquet A Jr. (2015). Posture Influence on the Pendulum Test of Spasticity in Patients with Spinal Cord Injury. Artif Organs 39(12), 1033–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V (2000). Spastic movement disorder. Spinal Cord 38(7), 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes S, Iddings JA, Ray S, Kirk-Sanchez NJ & Field-Fote EC. (2018). Comparison of Single-Session Dose Response Effects of Whole Body Vibration on Spasticity and Walking Speed in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Neurotherapeutics, 15(3), 684–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorassini MA, Knash ME, Harvey PJ, Bennett DJ & Yang JF. (2004). Role of motoneurons in the generation of muscle spasms after spinal cord injury. Brain 127(Pt 10), 2247–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ & Binder MD. (1991). Analysis of Ia-inhibitory synaptic input to cat spinal motoneurons evoked by vibration of antagonist muscles. J Neurophysiol 66(6), 1888–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD, Miller JF & Heckman CJ. (2007). Intrinsic electrical properties of spinal motoneurons vary with joint angle. Nat Neurosci 10(3), 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyngstrom A, Johnson M, Schuster J & Heckman CJ. (2008). Movement-related receptive fields of spinal motoneurons with active dendrites. J Physiol 586(6), 1581–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD & Heckman CJ. (2010). Interactions between focused synaptic inputs and diffuse neuromodulation in the spinal cord. Ann NY Acad Sci 1198, 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Kajtaz E, Cain CM & Heckman CJ. (2013). Motoneuron intrinsic properties, but not their receptive fields, recover in chronic spinal injury. J Neurosci 33(48), 18806–18813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakulas A (1988). The applied neurobiology of human spinal cord injury: a review. Paraplegia 26(6), 371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura J, Ise M & Tagami M. (1989). The clinical features of spasms in patients with a cervical spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 27(3), 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause JS, Carter RE & Pickelsimer E. (2009). Behavioral risk factors of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90(1), 95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JJ, Lee RH, Johnson MD, Heckman HM & Heckman CJ. (2003). Active dendritic integration of inhibitory synaptic inputs in vivo. J Neurophysiol 90(6), 3617–3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laessoe L, Nielsen JB, Biering-Sorensen F, & Sønksen J. (2004). Antispastic effect of penile vibration in men with spinal cord lesion. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 85(6), 919–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gorassini MA & Bennett DJ. (2004). Role of persistent sodium and calcium currents in motoneuron firing and spasticity in chronic spinal rats. J Neurophysiol 91(2), 767–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Li Y, Lucas-Osma AM, Hari K, Stephens MJ, Singla R, Heckman CJ, Zhang Y, Fouad K, Fenrich KK & Bennett DJ. (2019). Locomotor-related V3 interneurons initiate and coordinate muscles spasms after spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 121(4), 1352–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JW, Micklesen P, Umlauf R & Britell C. (1989). Lower extremity manifestations of spasticity in chronic spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 68(1), 32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell CW, Ivanova TD & Garland SJ. (2010). Changes in the estimated time course of the motoneuron afterhyperpolarization induced by tendon vibration. J Neurophysiol 104(6), 3240–3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BJ, Roll JP & Hugon M. (1990). Modulation of cutaneous flexor responses induced in man by vibration-elicited proprioceptive or exteroceptive inputs. Aviat Space Environ Med 61(10), 921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo M, DeForest BA, Castellanos M & Thomas CK. (2017). Characterization of Involuntary Contractions after Spinal Cord Injury Reveals Associations between Physiological and Self-Reported Measures of Spasticity. Front Integr Neurosci 11, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay WB, Sweatman WM & Field-Fote E. (2018). The experience of spasticity after spinal cord injury: perceived characteristics and impact on daily life. Spinal Cord 56(5), 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo N, Kumru H, Vidal-Samso J, Benito J, Medina J, Navarro X & Valls-Sole J. (2011). Decrease of spasticity with muscle vibration in patients with spinal cord injury. Clin Neurophysiol 122(6), 1183–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KC, Nakae A, Stephens MJ, Rank M, D’Amico J, Harvey PJ, Li X, Harris RL, Ballou EW, Anelli R, Heckman CJ, Mashimo T, Vavrek R, Sanelli L, Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ & Fouad K. (2010). Recovery of motoneuron and locomotor function after spinal cord injury depends on constitutive activity in 5-HT2C receptors. Nat Med 16(6), 694–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KC, Stephens MJ, Rank M, D’Amico J, Gorassini MA & Bennett DJ. (2011). Polysynaptic excitatory postsynaptic potentials that trigger spasms after spinal cord injury in rats are inhibited by 5-HT1B and 5-HT1F receptors. J Neurophysiol 106(2), 925–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness LL & Field-Fote EC. (2009). Effect of whole-body vibration on quadriceps spasticity in individuals with spastic hypertonia due to spinal cord injury. Restor Neurol Neurosci 27(6), 621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JB, Crone C, Hultborn H. (2007). The spinal pathophysiology of spasticity--from a basic science point of view. Acta Physiol 189(2), 171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton JA, Bennett DJ, Knash ME, Murray KC & Gorassini MA. (2008). Changes in sensory-evoked synaptic activation of motoneurons after spinal cord injury in man. Brain 131(Pt 6), 1478–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandyan AD, Gregoric M, Barnes MP, Wood D, Van Wijck F, Burridge J, Hermens H & Johnson GR. (2005). Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil 27(1–2), 2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn RD, Savoy SM, Corocos D, Latash M, Gottlieb G, Parke B & Kroin JS. (1989). Intrathecal baclofen for severe spinal spasticity. N Engl J Med 320(23), 1517–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Floeter MK & Field-Fote E. (2004). Repetitive sensory input increases reciprocal Ia inhibition in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurol Phys Ther 28(3), 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny E & Burke D. (2005). The circuitry of the human spinal cord: Its role in motor control and movement disorders. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Pressler RT & Regehr WG. (2013). Metabotropic glutamate receptors drive global persistent inhibition in the visual thalamus. J Neurosci 33(6), 2494–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe MM, Sherwood AM, Thornby JI, Kharas NF & Markowski J. (1996). Clinical assessment of spasticity in spinal cord injury: a multidimensional problem. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 77(7), 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank MM, Murray KC, Stephens MJ, D’Amico J, Gorassini MA & Bennett DJ. (2011). Adrenergic receptors modulate motoneuron excitability, sensory synaptic transmission and muscle spasms after chronic spinal cord injury. J Neurophysiol 105(1), 410–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot-Ciscar E, Rossi-Durand C & Roll JP. (1998). Muscle spindle activity following muscle tendon vibration in man. Neurosci Lett 258(3), 147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzmann R, Krause A, Freyler K & Gollhofer A. (2018). Acute whole-body vibration increases reciprocal inhibition. Hum Mov Sci 60, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JP, Vedel JP & Ribot E. (1989). Alteration of proprioceptive messages induced by tendon vibration in man: a microneurographic study. Exp Brain Res 76(1), 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo RE & Hounsgaard J. (1994). Short-term plasticity in turtle dorsal horn neurons mediated by L-type Ca2+ channels. Neuroscience, 61(2), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo RE & Hounsgaard J. (1996). Plateau-generating neurones in the dorsal horn in an in vitro preparation of the turtle spinal cord. J Physiol 493 (Pt 1), 39–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi M & Sawatzky B. (2014). Effects of vibration on spasticity in individuals with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 93(11), 995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangari S, Lundell H, Kirshblum S & Perez MA. (2019). Residual descending motor pathways influence spasticity after spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol 86(1), 28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmit BD & Benz EN. (2002). Extensor reflexes in human spinal cord injury: activation by hip proprioceptors. Exp Brain Res 145(4), 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HG, Oh BM, Leigh JH, Chun C, Park C & Kim CH. (2016). Effect of Focal Muscle Vibration on Calf Muscle Spasticity: A Proof-of-Concept Study. PM&R, 8(11), 1083–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M (2005). Effects of prolonged vibration on motor unit activity and motor performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37(12), 2120–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggelkow S, Kossev A, Schubert M, Kappels HH, Wolf W & Dengler R. (1999). Modulation of motor evoked potentials by muscle vibration: the role of vibration frequency. Muscle Nerve 22(11), 1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skold C, Levi R & Seiger A. (1999). Spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury: nature, severity, and location. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 80(12), 1548–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyvers M, Levin O, Verschueren SM & Swinnen SP. (2003). Frequency-dependent effects of muscle tendon vibration on corticospinal excitability: a TMS study. Exp Brain Res 151(1), 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Tecuapetla F, Koos T & Ibanez-Sandoval O. (2010). Heterogeneity and diversity of striatal GABAergic interneurons. Front Neuroanat 4, 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriault ER, Huang V, Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP & Harel NY. (2018). Antispasmodic medications may be associated with reduced recovery during inpatient rehabilitation after traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 41(1), 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki A, Butler M, Shamliyan T & Kane RL. (2011). Whole-body vibration therapy for osteoporosis: state of science. Ann Intern Med 155(10), 680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.