Abstract

Hepatic abscesses are rarely encountered in disseminated nocardia infections. We report a rare case of idiopathic Sweet syndrome (SS) who responded well to steroid therapy. However, he developed multiple abscesses in the lung, liver and spleen after 6 months of systemic steroid therapy. The culture result from liver abscess and sputum was diagnostic of disseminiated nocardiosis. Intravenous sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim was given and follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan revealed resolution of abscess. To conclude, nocardiosis should be suspected as a likely cause of lung, liver and spleen abscesses in patients undergoing long-term steroid treatment. A high index of clinical suspicion in patients with defects in cell-mediated immunity and prompt management by appropriate image studies are needed to prevent delay in diagnosis.

Keywords: disseminated nocardiosis, hepatic abscesses, steroid, Sweet syndrome

Introduction

Sweet syndrome (SS), is a group of diseases that present as an acute inflammatory skin eruption, fever and leukocytosis associated with histopathologic evidence of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the cutaneous lesions [1,2]. There are three clinical types of SS: classical or idiopathic SS, malignancy-associated or paraneoplastic SS, and drug-induced SS [3]. Systemic glucocorticoids are the first line treatment for SS. Systemic symptoms and cutaneous manifestations rapidly improve after starting therapy [4].

The risk of nocardial infection is increased in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with defects in cell-mediated immunity [5]. The lungs are the primary site of nocardial infection in more than twothirds of cases, and this organism can disseminate from a pulmonary or cutaneous focus to virtually any organ [6]. The other commonly involved sites include brain , bone, heart valves, joints, and kidneys [7]. Hepatic abscesses are rarely encountered in disseminated nocardiosis [8-10]. Herein we report a patient in whom hepatic nocardial abscesses developed after systemic steroid therapy for his SS.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man was admitted to our immunological division due to several days of fever, prolonged cough and dyspnea for 2 weeks. He also suffered from painful papules and nodules on the skin of the trunk and four limbs. Skin biopsy showed histopathologic evidence of dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Serum testing for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-RNP antibody Sm, SS-A/Ro, SS-B/La, centromere, Scl-70, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), and rheumatoid factor were all negative. SS was diagnosed after a series of examinations according to the revised set of diagnostic criteria [2]. He responded well to steroid therapy and underwent regular outpatient department follow-up. His initial prednisolone dosage was 30 mg/day and was tapered to 10 mg/day.

He was re-admitted at our infectious diseases division 5 months later due to prolonged cough, diarrhea and fever. Lung cancer was suspected initially by chest X-ray but image of chest computed tomography (CT) favored pulmonary tuberculosis. Aeromonas caviae was isolated from blood culture but absent in stool specimen. Ceftazidime was administered for one week according to antimicrobial susceptibility test. Moreover, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was isolated from sputum culture and anti-tuberculosis regimen consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyraziamide were prescribed initially. Isoniazid and rifampicin were later replaced with streptomycin due to allergic reaction.

Approximately two weeks after discharge, the patient returned to the emergency department (ED) with an acute onset of vomiting and fever. His initial vital signs were unremarkable except body temperature of 38.1°C. The physical examination revealed diminished breathing sound over right lung fi eld. Laboratory test and chest radiograph showed a leukocytosis and right pleural effusion respectively. A clinical diagnosis of sepsis was made since hypotension was noted. Resuscitation was performed using intravenous fluid, inotropic agents and empirical antibiotics.

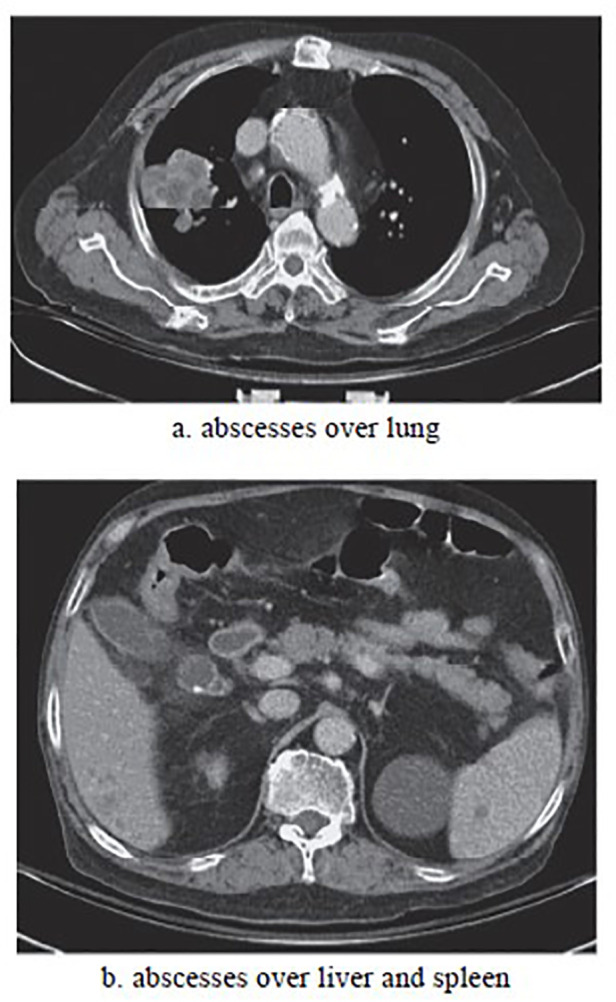

After admission, chest CT (Figure 1) revealed multiple abscesses in the lung, liver and spleen. Grampositive branched rods and weakly acid fast bacilli were found in specimen obtained via ultrasound guided aspiration of the liver abscess. Since Nocardia infection was suspected, intravenous sulfamethoxazoletrimethoprim (8 mg/kg iv of the trimethropim per day in 3 divided doses) was administered immediately. Afterwards, Nocardia species was isolated from the culture of sputum and liver abscess. Further identifications were not performed due to lack of molecular techniques at that time. Further hospital course was complicated by subsequent nosocominal pneumonia with respiratory failure, urinary tract infection and gastrointestinal bleeding. Due to difficult weaning course, tracheostomy was performed for respiratory care and patient was discharged from hospital 2 months later. A follow-up CT scan before discharge revealed resolution of abscesses. Unfortunately, he readmitted 3 months after this event due to subarachnoid hemorrhage and expired 2 days subsequently.

Figure 1. Abdomen computed tomography revealed multiple abscesses over lung, liver and spleen.

Discussion

Nocardia belongs to a genus of aerobic, grampositive, branching, filamentous, weakly acid-fast bacteria. They may cause localized or systemic suppurative disease in humans and animals [7]. Nocardia species are not usual normal human flora. They can be found in soil, rotten plants, dust, or water and can infect humans via skin inoculation or respiratory inhalation [9]. Inhalation of the organism is considered to be the most common mode of entry in western counties, which is supported in the literature by the observation that the majority of infections involve the lung [5]. In a recent retrospective survey of culture-proven nocardia infections in 81 patients with nocardiosis in Northern Taiwan [9], skin infections were the most common (n = 44, 54%) followed by localized pulmonary infections (n = 24, 30%) and disseminated infections (n = 13, 16%). Among 13 cases of disseminated nocardiosis, lung and brain involvement was found in 7 patients, brain and skin involvement in 2 patients. One case showed involvement with brain abscess, lung infection with bacteremia, lymphadenitis, and spontaneous peritonitis. There was no hepatic nocardiosis in those serial reports [9]. In another recent retrospective cohort study in a tertiary medical center in Israel involving 39 patients from a 15-year experience10, only seven (18%) patients were febrile (temperature above 38.0°C measured per rectum) on admission. About 10.5% of their patients had no evidence of infection at presentation, and the duration from the symptoms to admission require more than 1 month in 10.26%. A delayed period of over 10 days from admission to final diagnosis occurred in 38.46% of the cases. Disseminated diseases, defined as involvement of more than one organ or isolation of Nocardia from the bloodstream, were quite common consisting of almost 36% of patients. Among those with disseminated diseases, central nervous system (CNS) involvement was present in 35%, and no cases of hepatic involvement was seen in this study as well.10 From these reports, typical sites of disseminative nocardiosis include the lungs, skin, brain, and musculoskeletal system. Lesscommon sites include the pericardium, kidney, adrenal glands, eye, spleen, and liver [8].

Two main characteristics of nocardiosis deserve notice. First is its ability to disseminate to virtually any organ, particularly the central nervous system and second is its tendency to relapse or progress despite appropriate therapy [7]. Despite its aggressive nature, there are only some scattered reports of liver involvement in cases of nocardia infection in the literature [11-16]. Among the case series by Wang et al. [9] and Rosman et al. [10], there was no hepatic nocardiosis in those reports. The most comprehensive data about infective sites comprising 1050 cases of nocardiosis also found no liver involvement [7]. Nevertheless, hepato- pulmonary nocardiosis with abscesses have been reported in immunocompromised patients such as those with chronic granulomatous disease [12,13], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1], organ transplant recipients, [15,16] and those on long-term steroid use [11] (and our present case). From our clinical experience and other reported sporadic case reports of hepatic nocardiosis, the hallmark of extrapulmonary nocardiosis is abscess formation and can resemble a pyogenic bacterial process. This usually occurs through hematogenous dissemination [8]. The clinical presentation may include fever, abdominal pain, vomiting and leukocytosis, but the chemical liver function tests and abdominal ultrasonography might be initially negative [16]. The reasons for the low occurrence rate in the liver remain unclear. First, liver nocardiosis may be underdiagnosed because of the relatively slow growth of the organism. Some culture negative liver abscesses may be mistakenly diagnosed as other entities. Secondly, some cases of liver nocardiosis may have a fulminate course resulting in mortality before the initiation of image studies. To prevent delayed diagnosis, a high index of clinical suspicion in patients with defects in cell-mediated immunity and timely management by appropriate image studies are needed.

Our patient responded well to oral corticosteroids for his SS within a few weeks. However, prolonged steroid use predisposed him to contract pulmonary tuberculosis at the same time. The total reported case numbers of coexisting pulmonary tuberculosis with nocardiosis has been very few [1]. Our review found a case series of 5 out of 24 cases of localized pulmonary nocardial infections associated with active pulmonary tuberculosis [9]. Concomitant infection with Mycobacterium species has also been implicated as a risk factor for development of nocardiosis in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients [17]. Impaired cell-mediated immunity seemed to be a major predisposed factor for comorbidity of tuberculosis with nocardiosis in our patient.

In conclusion, we report a case of SS requiring prolonged oral corticosteroids, which predisposed him to be infected with pulmonary tuberculosis and disseminated nocardiosis with liver involvement. Lung and disseminated nocardiosis can be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in patients receiving immunosuppressive agents. Early recognition of nocardiosis enables a more rapid initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy and subsequently a favorable outcome.

References

- 1.SWEET R. B. AN ACUTE FEBRILE NEUTROPHTLIC DERMATOSTS. British Journal of Dermatology. 1964 Aug;76(8-9) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1964.tb14541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen Philip R., Kurzrock Razelle. Sweet's syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. International Journal of Dermatology. 2003 Oct;42(10) doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen Philip R, Kurzrock Razelle. Sweet’s syndrome: a neutrophilic dermatosis classically associated with acute onset and fever. Clinics in Dermatology. 2000 May;18(3) doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(99)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma R, Vasudevan B, Pragasam V, Mitra D. Unusual presentation of idiopathic sweet′s syndrome in a photodistributed pattern. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2014;59(2) doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.127682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorrel TC, Mitchell DH, Iredell JR, Chen SC-A. Nocardia species In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederman Edith R., Crum Nancy F. A Case Series and Focused Review of Nocardiosis. Medicine. 2004 Sep;83(5) doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000141100.30871.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaman B L, Beaman L. Nocardia species: host-parasite relationships. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1994 Apr;7(2) doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson John W. Nocardiosis: Updates and Clinical Overview. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2012 Apr;87(4) doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Hua-Kung, Sheng Wang-Huei, Hung Chien-Ching, Chen Yee-Chun, Lee Mong-Hong, Lin Wagner S., Hsueh Po-Ren, Chang Shan-Chwen. Clinical characteristics, microbiology, and outcomes for patients with lung and disseminated nocardiosis in a tertiary hospital. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2015 Aug;114(8) doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosman Yossi, Grossman Ehud, Keller Nathan, Thaler Michael, Eviatar Tali, Hoffman Chen, Apter Sarah. Nocardiosis: A 15-year experience in a tertiary medical center in Israel. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2013 Sep;24(6) doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cockerill Franklin R., Edson Randall S., Roberts Glenn D., Waldorf James C. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-resistant nocardia asteroides causing multiple hepatic abscesses. The American Journal of Medicine. 1984 Sep;77(3) doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sponseller P D, Malech H L, McCarthy E F, Horowitz S F, Jaffe G, Gallin J I. Skeletal involvement in children who have chronic granulomatous disease. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1991 Jan;73(1) doi: 10.2106/00004623-199173010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNeil M. M., Brown J. M., Magruder C. H., Shearlock K. T., Saul R. A., Allred D. P., Ajello L. Disseminated Nocardia transvalensis Infection: An Unusual Opportunistic Pathogen in Severely Immunocompromised Patients. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1992 Jan 01;165(1) doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramseyer L T, Nguyen D L. Nocardia brasiliensis liver abscesses in an AIDS patient: imaging findings. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1993 Apr;160(4) doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.4.8456695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott MA, Tefferi A, Marshall WF, Lacy MQ. Disseminated nocardiosis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997 Sep;20(5) doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanchanale Pavan, Jain Mayank, Varghese Joy, V Jayanthi, Rela Mohamed. Nocardialiver abscess post liver transplantation-A rare presentation. Transplant Infectious Disease. 2017 Mar 06;19(2) doi: 10.1111/tid.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qureshi S, Pandey A, Sirohi TR, Verma SR, Sardana V, Agrawal C, Asthana AK, Madan M. Mixed pulmonary infection in an immunocompromised patient: A rare case report. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2014;32(1) doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.124330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]