Abstract

Background

The aim of our study was to compare the Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock (AIMS65) score with the Modifi ed Early Warning Score (MEWS), quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score, Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS), and the complete Rockall score (CRS) in predicting clinical outcomes in cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).

Methods

A total of 442 consecutive cirrhotic patients admitted with UGIB during a 17-month period were retrospectively investigated. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes were rebleeding, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and development of infection. The area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for each system was analyzed.

Results

For prediction of mortality, the AUC of the AIMS65 score was greater than that of other scoring systems without statistical signifi cance. For the prediction of rebleeding, the AIMS65 score was superior to qSOFA (0.65 vs. 0.56, p = 0.020). For the prediction of ICU admission, the AIMS65 score was superior to the GBS and CRS (0.77 vs. 0.63, p = 0.005 and 0.77 vs. 0.63, p = 0.007, respectively). For the prediction of the development of infection, the AIMS65 score was superior to CRS (0.73 vs. 0.60, p = 0.010).

Conclusions

In predicting in-hospital mortality among cirrhotic patients with UGIB, the AIMS65 score showed a trend of better performance than the MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS. The AUCs of the AIMS65 score were greater than other four systems in predicting rebleeding, ICU admission and the development of infection.

Keywords: upper gastrointestinal bleeding, AIMS65, qSOFA, Glasgow-Blatchford score, Rockall score

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a frequent and fatal medical emergency, particularly among patients with cirrhosis, with a mortality rate of 5% to 17%. [1-8] However, there are few studies comparing these scoring systems in predicting adverse outcomes of UGIB in cirrhotic patients. Currently, most articles on the predictors of clinical outcomes for cirrhotic patients with UGIB have largely focused on variceal bleeding, which accounts for 55% to 87% of bleeding episodes. [5,6,8,9] The results of these studies may be of limited use when the bleeding source has not yet been identified on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopic examination. A simple, readily available, and precise scoring system to classify patients according to severity and to identify unstable patients would allow physicians to implement the correct treatment protocol for effective treatment and enable the proper allocation of resources.

Several scoring systems have been developed to predict the prognosis of UGIB. The Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock (AIMS65) score, a recently proposed scoring system to predict mortality in acute UGIB, has been validated as a simple, accurate, unweighted, non-endoscopic system with predictive value that is comparable or superior to the Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS) and complete Rockall score (CRS), the two currently most widely used stratification tools in UGIB. [10-16] The Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) system permits rapid calculation, based on clinical variablesand may help to identify critical or potentially critical UGIB patients. [17]

Infection in cirrhotic patients with UGIB increases the risk of failure to control bleeding, therebleeding rate, and mortality. [4,18-20] The quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA), also known as quickSOFA, is a novel scoring system developed to identify poor prognosis in patients with suspected infection. [21] Considering the significance of infection in patients with cirrhosis and the ability of the qSOFA for prognosis prediction in sepsis, qSOFA may help to recognize UGIB patients with possible unfavorable outcomes.

In this study, we compared the five most commonly used scoring systems—the AIMS65 score, MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS—for predicting the clinical outcome of cirrhotic patients with UGIB from all sources. We hypothesized that the AIMS65 score had the potential to become the new standard risk score for cirrhotic patients with UGIB due to its simplicity, accuracy, and convenience. Outcomes were assessed in terms of in-hospital mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and the development of infection.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a retrospective study conducted in two hospitals: a medical center (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou branch) and a regional hospital (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi branch); both hospitals were university-affiliated teaching hospitals.All adult (> 18-year-old) patients with cirrhosis presenting with UGIB to the emergency department (ED) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou branch between August 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010, and those presenting to the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi branch ED between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011, were reviewed for eligibility for inclusion.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital and informed consent was waived.

Survey Content and Administration

The medical records of all adult cirrhotic patients presenting with UGIB to the ED were reviewed. The diagnosis of UGI bleeding was made based on the following clinical manifestations: hematemesis, vomiting with coffee ground substance, melena, or blood from nasogastric tube aspiration. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was confirmed based on compatible abdomen sonographic findings accompanied by laboratory findings of hepatic dysfunction or clinical findings of portal hypertension. Child–Pugh classification (CP classification) A, B, or C was used to classify the severity of cirrhosis. [22] CP classification A denotes good hepatic function, CP classification B denotes intermediate hepatic function, and CP classification C poor function. Shock was defined as signs of shock at ED triage, including systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg and pulse rate > 100 beats/min. All patientsunderwent UGI endoscopy to confirm the source of hemorrhage. Variceal bleeding was diagnosed via endoscopic findings, including active hemorrhage from any varices, the presence of a clot over any varices, or the presence of blood in the stomach with varices asthe only potential source of bleeding. Those patients not diagnosed as having variceal bleeding were classified as having non-variceal bleeding. Patients were excluded if endoscopy was not performed. All cirrhotic patients with UGI bleeding were treated following a standardized protocol, including fluid resuscitation, vasoactive drugs, antibiotics, and high-dose acid suppression therapy, according to each hospital practiceguidelines. Clinical variables, including age, sex, clinical presentation of bleeding, vital signs, laboratory data, comorbidities, findings on endoscopic examination, the need for ICU admission, development of infection, rebleeding, and in-hospital mortalitywere recorded. ICU admission was indicated when a patient had respiratory failure with mechanical ventilation support or had signs of hemodynamic instability despite adequate fluid resuscitation and medical treatment. The development of infection in our studywas defined as any clinical symptoms and signs of suspected infections, such as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, [21] spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, urinary tract infection, pneumonia on chest radiograph, plus a positive bacterial culture of any specimen, including sputum, urine, blood, and ascites during hospitalization for UGIB. Rebleeding was defined as any of the following: (1) repeated endoscopy within 3 days, (2) continuous blood transfusion for more than 3 days, or (3) surgical intervention to control bleeding within 3 days. The AIMS65 score, MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS were calculated for all patients enrolled in the study. The methods for calculating these scores were based on the original articles [21,23-26] (Supplement Tables 4-7).

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes were rate of rebleeding, ICU admission, and development of infection.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Med-Calc Statistical Software version 17.0.4 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium). Normally distributed data are presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) and data with skewed distribution are expressed as median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for primary and secondary outcomes and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated for each score and outcome. The optimal thresholds of the AIMS65 score, MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS were identified as the threshold associated with the highest Youden index. The difference between two AUC values was analyzed using the method set out by DeLong et al. [27] The difference was considered significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Sensitivity Analysis

To test the robustness of the main results, several additional analyses were conducted. A subgroup analysis was conducted by stratifying causes of bleeding into variceal bleeding and non-variceal bleeding.

Results

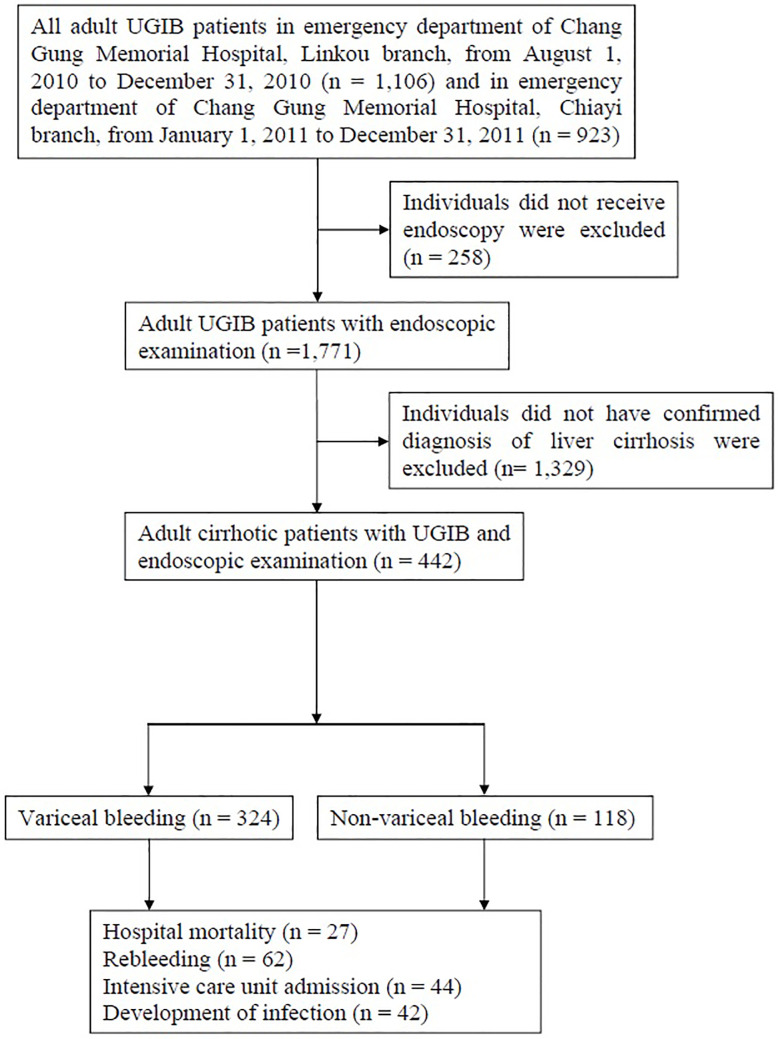

Figure 1 illustrates the selection process of study participants. A total of 442 patients with cirrhosis were enrolled in the study and underwent endoscopy for UGIB. Of these, over half (51.6%) were male and 31.2% were over 65 years of age. The mean level of hemoglobin was 9.1 (± 2.4) g/dL. The median AIMS65 score, MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS was 1 (IQR = 0–2), 3 (IQR = 1–4), 0 (IQR = 0–1), 10 (IQR = 8–13), and 9 (IQR = 7–9), respectively. Of the 442 patients, 27 died (in-hospital mortality rate 6.1%). The clinical characteristics and demographic data of patients are shown in Table 1. The ROC curve and AUC, with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p value, are shown in Table 2. Comparisons between each two scoring systems regarding in-hospital mortality, rebleeding, ICU admission rate, and development of infection, are presented in Table 3.

Figure 1. Fig. 1.

Flow chart of identification of study participants. Patients enrolled in the study; number of patients included in and excluded from the study. Adult patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) were included. Individuals who did not receive endoscopy and those who did not have a confirmed diagnosis of liver cirrhosis were excluded.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients.

ICU: intensive care unit.

aShock was defined as signs of shock at emergency department triage, including systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg and pulse rate > 100 beats/min.

* p < 0.05.

|

|

All n (%) |

Variceal bleeding n (%) |

Non-variceal bleeding n (%) |

p value |

|

||||||

|

Number of patients |

442 (100.0) |

324 (73.3) |

118 (26.7) |

|

|

||||||

|

Age > 65 years |

138 (31.2) |

84 (25.9) |

54 (45.8) |

< 0.001* |

|

||||||

|

Male sex |

228 (51.6) |

152 (46.9) |

76 (64.4) |

0.001 |

|

||||||

|

Endoscopic findings |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Esophageal varices |

345 (78.0) |

303 (93.5) |

42 (35.5) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Gastric varices |

184 (41.6) |

153 (47.2) |

31 (26.2) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Gastric ulcer |

120 (27.1) |

49 (15.1) |

71 (60.2) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Duodenal ulcer |

66 (14.9) |

18 (5.6) |

48 (40.7) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

Causes of bleeding |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Esophageal varices |

295 (66.7) |

295 (91.0) |

— |

— |

||||||

|

|

Gastric varices |

29 (6.6) |

29 (9.0) |

— |

— |

||||||

|

|

Gastric ulcer |

64 (14.5) |

— |

64 (54.2) |

— |

||||||

|

|

Duodenal ulcer |

45 (10.2) |

— |

45 (38.1) |

— |

||||||

|

|

Other |

9 (2.0) |

— |

9 (7.6) |

— |

||||||

|

Child–Pugh class of liver cirrhosis |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Child–Pugh class A |

158 (35.7) |

104 (32.1) |

54 (45.8) |

0.008* |

||||||

|

|

Child–Pugh class B |

169 (38.2) |

139 (42.9) |

30 (25.4) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Child–Pugh class B |

115 (26.0) |

81 (25.0) |

34 (28.8) |

0.419 |

||||||

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Heart failure |

22 (5.0) |

14 (4.3) |

8 (6.8) |

0.283 |

||||||

|

|

Ischemic heart disease |

61 (13.8) |

24 (7.4) |

37 (31.4) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Renal failure |

73 (16.5) |

42 (13.0) |

31 (26.3) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Metastatic cancer |

66 (14.9) |

45 (13.9) |

21 (17.8) |

0.308 |

||||||

|

Hemodynamic status at triage |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Shocka |

54 (12.2) |

43 (13.3) |

11 (9.3) |

0.262 |

||||||

|

Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Blood transfusion |

196 (44.3) |

147 (45.4) |

49 (41.5) |

0.472 |

||||||

|

|

Fresh frozen plasma |

84 (19.0) |

76 (23.5) |

8 (6.8) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

|

Endoscopic treatment |

243 (55.0) |

212 (65.4) |

31 (26.3) |

< 0.001* |

||||||

|

Outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Mortality |

27 (6.1) |

18 (5.6) |

9 (7.6) |

0.421 |

||||||

|

|

Rebleeding |

62 (19.9) |

58 (21.8) |

4 (8.9) |

0.002* |

||||||

|

|

ICU admission |

44 (10.0) |

39 (12.0) |

5 (4.2) |

0.015* |

||||||

|

|

Development of infection |

42 (9.5) |

36 (11.1) |

6 (5.1) |

0.056 |

||||||

Table 2. Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock, Modified Early Warning Score, quick Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment, Glasgow-Blatchford score,and Rockall score for the outcomes.

AIMS65: Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock; AUC: area under receiver operating characteristic curve; CI: confidence interval; CRS: complete Rockall score; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score; ICU: intensive care unit; MEWS: Modified Early Warning Score; qSOFA: quick Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment.

|

Outcome and scoring system |

AUC |

95% CI |

|

|||

|

Mortality |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.76 |

0.71–0.80 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.67 |

0.62–0.71 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.72 |

0.67–0.75 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.71 |

0.66–0.75 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.64 |

0.60–0.69 |

|||

|

Rebleeding |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.65 |

0.60–0.70 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.58 |

0.53–0.64 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.56 |

0.51–0.62 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.62 |

0.57–0.68 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.58 |

0.52–0.63 |

|||

|

ICU admission |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.77 |

0.73–0.81 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.74 |

0.69–0.78 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.75 |

0.70–0.79 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.63 |

0.58–0.67 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.63 |

0.59–0.68 |

|||

|

Development of infection |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS |

0.73 |

0.69–0.77 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.69 |

0.65–0.74 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.71 |

0.66–0.75 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.64 |

0.60–0.69 |

|||

|

CRS |

0.60 |

0.55–0.64 |

|

|||

Table 3. Comparison of receiver operation curve curves for Age 65; International normalizedratio; Mental status; Shock, Modified Early Warning Score, quick Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and complete Rockall score.

AIMS65: Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock; CRS: complete Rockall score; DBA: difference between area; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score; ICU: intensive care unit; MEWS: Modified Early Warning Score; qSOFA: quick Sepsis OrganFailure Assessment.

* p < 0.05.

|

Outcome and scoring system |

DBA |

p value |

|

|||

|

Mortality |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. MEWS |

0.087 |

0.140 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. qSOFA |

0.045 |

0.442 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. GBS |

0.051 |

0.365 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. CRS |

0.113 |

0.070 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. qSOFA |

0.043 |

0.351 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. GBS |

0.037 |

0.527 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. CRS |

0.026 |

0.670 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. GBS |

0.006 |

0.904 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. CRS |

0.069 |

0.274 |

|||

|

|

GBS vs. CRS |

0.063 |

0.204 |

|||

|

Rebleeding |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. MEWS |

0.068 |

0.141 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. qSOFA |

0.087 |

0.020* |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. GBS |

0.029 |

0.440 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. CRS |

0.074 |

0.074 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. qSOFA |

0.019 |

0.568 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. GBS |

0.039 |

0.391 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. CRS |

0.005 |

0.894 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. GBS |

0.058 |

0.121 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. CRS |

0.013 |

0.729 |

|||

|

|

GBS vs. CRS |

0.044 |

0.276 |

|||

|

ICU admission |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. MEWS |

0.033 |

0.561 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. qSOFA |

0.022 |

0.645 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. GBS |

0.142 |

0.005* |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. CRS |

0.136 |

0.007* |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. qSOFA |

0.011 |

0.724 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. GBS |

0.109 |

0.030* |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. CRS |

0.103 |

0.047* |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. GBS |

0.120 |

0.005* |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. CRS |

0.114 |

0.012* |

|||

|

|

GBS vs. CRS |

0.006 |

0.909 |

|||

|

Development of infection |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. MEWS |

0.032 |

0.534 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. qSOFA |

0.024 |

0.566 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. GBS |

0.085 |

0.090 |

|||

|

|

AIMS65 vs. CRS |

0.134 |

0.010* |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. qSOFA |

0.008 |

0.804 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. GBS |

0.053 |

0.266 |

|||

|

|

MEWS vs. CRS |

0.048 |

0.035* |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. GBS |

0.061 |

0.157 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA vs. CRS |

0.110 |

0.022* |

|||

|

GBS vs. CRS |

0.048 |

0.309 |

|

|||

For the prediction of mortality, the AUC was obtained for the AIMS65 score = 0.76 (95% CI = 0.71–0.80), MEWS = 0.67 (95% CI = 0.62–0.71), qSOFA score = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.67–0.75), GBS = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.66–0.75), and CRS = 0.64 (95% CI = 0.60–0.69). The AUC of the AIMS65 score was greater than that of the other scoring systems, without statistical significance (Table 3). The in-hospital mortality cutoff point that maximized the sum of the sensitivity and specificity was 1 for the AIMS65 score (sensitivity = 0.78, specificity = 0.67, total = 1.45), 4 for MEWS (sensitivity = 0.41, specificity = 0.88, total = 1.29), 0 for qSOFA (sensitivity = 0.74, specificity = 0.65, total = 1.39), 9 for GBS (sensitivity = 0.96, specificity = 0.47, total = 1.43), and 7 for CRS (sensitivity = 0.89, specificity = 0.34, total = 1.23).

For the prediction of rebleeding, the AUC was obtained for the AIMS65 score = 0.65 (95% CI = 0.60–0.70), MEWS = 0.58 (95% CI = 0.53–0.64), qSOFA = 0.56 (95% CI = 0.51–0.62), GBS = 0.62 (95% CI = 0.57–0.68), and CRS = 0.58 (95% CI = 0.52–0.63). The AIMS65 score was comparable to the MEWS, GBS, and CRS (p = 0.141, 0.440, and 0.074, respectively) and superior to the qSOFA (p = 0.020) in predicting rebleeding (Table 3).

The rebleeding cutoff point that maximized the sum of the sensitivity and specificity was 1 for the AIMS65 score (sensitivity = 0.54, specificity = 0.66, total = 1.20), 1 for MEWS (sensitivity = 0.82, specificity = 0.33, total = 1.15), 1 for qSOFA (sensitivity = 0.22, specificity = 0.91, total = 1.13), 7 for GBS (sensitivity = 0.93, specificity = 0.24, total = 1.17), and 8 for CRS (sensitivity = 0.61, specificity = 0.52, total = 1.13).

For the prediction of ICU admission, the AUC was obtained for the AIMS65 score = 0.77 (95% CI = 0.73–0.81), MEWS = 0.74 (95% CI = 0.69–0.78), qSOFA = 0.75 (95% CI = 0.70–0.79), GBS = 0.63 (95% CI = 0.58–0.67), and CRS = 0.63 (95% CI = 0.59–0.68). The AIMS65 score was comparable to the MEWS and qSOFA (p = 0.561 and 0.645, respectively) and superior to the GBS and CRS (p = 0.005 and 0.007, respectively) in predicting ICU admission (Table 3).

The ICU admission cutoff point that maximized the sum of the sensitivity and specificity was 2 for the AIMS65 score (sensitivity = 0.46, specificity = 0.93, total = 1.39), 4 for MEWS (sensitivity = 0.55, specificity = 0.91, total = 1.46), 0 for qSOFA (sensitivity = 0.75, specificity = 0.66, total = 1.41), 10 for GBS (sensitivity = 0.75, specificity = 0.54, total = 1.29), and 8 for CRS (sensitivity = 0.68, specificity = 0.51, total = 1.19).

For predicting the development of infection, the AUC was obtained for the AIMS65 score = 0.73 (95% CI = 0.69–0.77), MEWS = 0.69 (95% CI = 0.65–0.74), qSOFA = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.66–0.75), GBS = 0.64 (95% CI = 0.60–0.69), and CRS = 0.60 (95% CI = 0.55–0.64). The AIMS65 score was comparable to the MEWS, qSOFA, and GBS (p = 0.534, 0.566, and 0.090 respectively) and superior to the CRS (p = 0.010) in predicting the development of infection (Table 3).

The cutoff point for development of infection that maximized the sum of the sensitivity and specificity was 1 for the AIMS65 score (sensitivity = 0.66, specificity = 0.68, total = 1.34), 3 for MEWS (sensitivity = 0.52, specificity = 0.75, total = 1.27), 0 for qSOFA (sensitivity = 0.71, specificity = 0.65, total = 1.36), 9 for GBS (sensitivity = 0.76, specificity = 0.47, total = 1.23), and 7 for CRS (sensitivity = 0.88, specificity = 0.34, total = 1.22).

Sensitivity Analysis

The results of subgroup analysis presented that the AIMS65 was a better scoring system in predicting in-hospital mortality in both variceal bleeding group and non-variceal bleeding group than others (Supplement Tables 8,9).

Discussion

In Table 1, significant differences between the two groups (variceal bleeding and non-variceal bleeding) were noted in many variables, including age, sex, endoscopic findings, CP classification, comorbidities, and treatments. The reason for the differences in variablesis that the pathophysiology is quite different between variceal and non-variceal. [28] In non-variceal bleeding, the causes of bleeding are mainly owing to ulcerative or erosive lesions whereas variceal bleeding mostly results from complications of portal hypertension. [29] In addition, in patients with non-variceal bleeding, a history of Helicobacter pylori infection or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin is prevalent; in patients with variceal bleeding, a history of liver disease or alcohol abuse is more common. [6,30] In our study, the higher proportion of patients with CP classification A implies that there were possibly fewer complications of portal hypertension, such as seen in variceal bleeding. A higher proportion of patients with ischemic heart disease in the non-variceal bleeding group suggests a possible greater use of low-dose aspirin, increasing the risk of ulcer bleeding. [31] The slightly higher rate of mortality in the non-variceal bleeding group may be due to more older-aged patients or a higher proportion of patients with comorbidities of ischemic heart disease and renal disease. [6] In fact, although the mortality was slightly higher in the group with non-variceal bleeding, no significance was noted as compared with the variceal bleeding group (p = 0.421). Further prospective studies including a large number of patients and focusing on cirrhotic patients with UGIB are needed.

The results of the present study showed that the AIMS65 score had the greatest AUC values, compared with the MEWS, qSOFA, GBS, and CRS, for detecting in-hospital mortality. After adjusting the p value to < 0.1, the AIMS65 score was superior to theCRS (p = 0.070). There are few studies comparing scoring systems among cirrhotic patients with UGIB, and most of these studies have focused on variceal bleeding. The AIMS65 score is comparable to the CRS in predicting in-hospital mortality [11,12] and superior to the GBS and pre-endoscopy Rockall score (PRS) [10,12,13,15,16] in serial UGIB studies. Among studies of variceal bleeding, the AIMS65 score has been found to be more accurate than the CRS in predicting in-hospital mortality, [32] and is comparable to the PRS and GBS in predicting 30-day mortality. [33] Previous reports have indicated that the AIMS65 score is superior to the SOFA score, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and CP classification in predicting mortality in patients with variceal bleeding. [34] In a recent study, Bozkurt et al. [17] confirmed that the MEWS was as effective as the GBS and Rockall score in predicting in-hospital mortality. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to include the qSOFA and MEWS for the prediction of mortality in cirrhotic patients with UGIB, and our findings suggest that the AIMS65 score is comparable to other scoring systems.

In this study, we did not find any differences in performance between the AIMS65 score, MEWS, GBS, and CRS in the prediction of rebleeding; however, the AIMS65 score was superior to the qSOFA score (0.65 vs. 0.56, p = 0.020). The AUC values of these five scoring systems were between 0.56 and 0.65, implying that the clinical application of these systems in predicting rebleeding is limited. In agreement with a prospective study in Denmark, our data revealed similar performance of the CRS to detect rebleeding; the authors of that study found similarly low AUC values. [35] Also similar to our report, a recent investigation in Peru revealed that the GBS, CRS, and AIMS65 score were comparable in predicting rebleeding. [36] Recent prospective research in China has demonstrated that the AIMS65 score had better performance for predicting rebleeding than the GBS (AUC = 0.74 vs. 0.62, p = 0.01). [37] In contrast, another report from Mexico showed that the GBS (AUC = 0.76) was a better scoring system than the CRS (AUC = 0.69) and AIMS65 score (AUC = 0.66) for prediction of rebleeding, although no significant difference was noted (p = 0.28). [38] These discrepant findings in reports from different countries suggest that a new scoring system with performance that is superior to the current five scoring systems for rebleeding is required.

A simple and accurate scoring system to predict ICU admission is crucial for physicians, to enable them to commence appropriate resuscitation and make prompt specialist referral for urgent endoscopy. Previous studies have reported various results regarding this aspect. Hyett et al. [16] reported that the AIMS65 score had greater AUC values than the GBS, although this was not statistically significant (AUC = 0.69 vs. 0.63, p = 0.35). A prospective study from Turkey [14] revealed that the GBS had superior discriminatory power compared with the AIMS65 score (AUC = 0.80 vs. 0.75, p = 0.137) for composite clinical outcomes, defined as the need for surgical or endoscopic intervention, rebleeding, ICU admission, or in-hospital mortality, although this was not statistically significant. A more recent study conducted by Robertson et al. [12] showed that the AIMS65 score was superior to all other scores, including the GBS, PRS, and CRS (AUC = 0.74 vs. 0.70 vs. 0.62 vs. 0.71, respectively). There are limited reports on scoring systems or factors predicting ICU admission in patients with variceal bleeding and cirrhotic patients with UGIB from all sources.

Our study showed that the differences in AUC values between the AIMS65 score and GBS and between the AIMS65 and CRS in predicting ICU admission were statistically significant (p = 0.005 and 0.007, respectively). Furthermore, no differences were noted in AUC values between the AIMS65 score and MEWS or between the AIMS65 and qSOFA scores. The AIMS65, MEWS, and qSOFA may be valuable for early risk stratification of cirrhotic patients with UGIB, to prioritize ICU admission.

It is known that bacterial infection is frequently diagnosed in cirrhotic patients with UGIB, including those with variceal and non-variceal bleeding. [2,18-20] Bacterial infection is independently associated with multiple adverse outcomes (failure to control bleeding, recurrent bleeding episodes, in-hospital mortality) in cirrhotic patients with UGIB. [4,18-20] Timely antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the infection rate, in-hospital mortality, rebleeding episodes, days of hospitalization, and improves patient outcome. [1,2,38,39] A scoring system identifying patient groups that are likely to develop infection is crucial for physicians to select the most effective antibiotic and promptly administer antibioticprophylaxis. The results of our study indicate that the AIMS65 score had greater AUC values than those of the MEWS and qSOFA scores, although without statistical significance. However, the difference in AUC values between the AIMS65 score and CRS wassignificant (p = 0.010). The AIMS65 score may be the most appropriate tool to predict the development of infection in cirrhotic patients with UGIB in the ED.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, our study had a retrospective design and some data were unavailable or incomplete. However, we enrolled consecutive patients who fulfilled clearly defined inclusion criteria. We also reviewed individual charts using a standardized data collection tool to minimize variability. Second, our study included only two institutions. However, these were large-scale hospitals and urgent endoscopy is available 24 hours, 7 days a week in both hospitals. Therefore, patients with UGIB in critical condition are frequently transferred from neighboring cities to these hospitals.

Conclusions

The AIMS65 score is a better predictor of in-hospital mortality among cirrhotic patients with UGIB than the MEWS, qSOFA score, GBS, and CRS. The AUC values of the AIMS65 score were greater than those of the other four systems in predicting rebleeding, ICU admission, and the development of infection. This study proved that the AIMS65 score canbe applied to cirrhotic patient with all-source UGIB for the prediction of outcomes. The AIMS65 score is a simple, unweighted score, which is easy to calculate and does not rely on endoscopic examination.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the staff members of participating hospitals for the care of the investigated patients and for their help in collecting data.

Author Contributions

Yi-Chen Lai, Yi-Chuan Chen, Ming-Szu Hung and Yu-Han Chen conceived the study, designed the method. Yi-Chuan Chen and Ming-Szu Hung supervised the conduct of the data collection. Yi-Chuan Chen and Ming-Szu Hung undertook recruitment of participating centers and patients and managed the data, including quality control. Yi-Chuan Chen and Ming-Szu Hung provided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data; Yi-Chuan Chen chaired the data oversight committee. Yi-Chen Lai, Yi-Chuan Chen, Ming-Szu Hung, and Yu-Han Chen drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. Yi-Chuan Chen takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement Table 1. Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock and Glasgow-Blatchford score.

AIMS65: Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock; INR: international normalized ratio; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

|

Variables |

Score |

|

|||||

|

AIMS65 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

Albumin < 3.0 mg/dL |

1 |

|

||||

|

|

INR > 1.5 |

1 |

|

||||

|

|

Altered mental status |

1 |

|

||||

|

|

SBP < 90 mmHg |

1 |

|

||||

|

|

Age > 65 years |

1 |

|

||||

|

|

Maximum |

5 |

|

||||

|

Glasgow-Blatchford score |

|

|

|||||

|

Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) |

|

|

|||||

|

|

18.2–22.3 |

2 |

|||||

|

|

22.4–27.9 |

3 |

|||||

|

|

28.0–69.9 |

4 |

|||||

|

|

≥ 70.0 |

6 |

|||||

|

|

Hemoglobin, men (g/dL) |

|

|

||||

|

|

12.0–12.9 |

1 |

|||||

|

|

10.0–11.9 |

3 |

|||||

|

|

< 10.0 |

6 |

|||||

|

Hemoglobin, women (g/dL) |

|

|

|||||

|

|

10.0–11.9 |

1 |

|||||

|

|

< 10.0 |

6 |

|||||

|

SBP (mmHg) |

|

|

|||||

|

|

100–109 |

1 |

|||||

|

|

90–99 |

2 |

|||||

|

|

< 90 |

3 |

|||||

|

Other markers |

|

|

|||||

|

|

Pulse ≥ 100/min |

1 |

|||||

|

|

Presentation with melena |

1 |

|||||

|

|

Presentation with syncope |

2 |

|||||

|

|

Hepatic disease |

2 |

|||||

|

|

Heart failure |

2 |

|||||

|

Maximum |

23 |

|

|||||

Supplement Table 2. Rockall scorea.

CHF: congestive heart failure; HR, heart rate; IHD: ischemic heart disease; SBP: systolic blood pressure; UGI: upper gastrointestinal.

aPre-endoscopic Rockall score = score of age + score of shock + score of comorbidity (maximum score = 7); complete Rockall score = clinical Rockall score + score of diagnosis + score of stigmata of recent hemorrhage (maximum score = 11).

|

Variable |

Score |

|||

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Age (years) |

60 |

60–79 |

≥ 80 |

|

|

Shock |

|

HR > 100 |

SBP < 100 mmHg |

|

|

Comorbidity |

|

|

IHD, CHF, any major comorbidity |

Renal failure, liver failure, metastatic malignancy |

|

Diagnosis |

Mallory–Weiss tear or no lesion observed |

Peptic ulcer disease, erosive esophagitis |

UGI tract malignancy |

|

|

Stigmata of recent hemorrhage |

Clean-based ulcer, flat pigmented spot |

|

Blood in UGI tract, clot, visible vessel, bleeding |

|

Supplement Table 3. Quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessmenta.

SBP: systolic blood pressure.

aMaximum score = 3.

|

|

Scorea |

|

Altered mental status (Glasgow Coma Scale < 15) |

1 |

|

respiratory rate ≥ 22 |

1 |

|

SBP ≤ 100 mmHg |

1 |

Supplement Table 4. Modified Early Warning Score.

AVPU: alert, voice, pain, unresponsive scale; HR: heart rate; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

|

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

SBP (mmHg) |

< 70 |

71–80 |

81–100 |

101–199 |

|

≥ 200 |

|

|

HR (bpm) |

|

< 40 |

41–50 |

51–100 |

101–110 |

111–129 |

≥ 130 |

|

Respiratory rate (bpm) |

|

< 9 |

|

9–14 |

15–20 |

21–29 |

≥ 30 |

|

Temperature (°C) |

|

< 35.0 |

|

35.0–38.4 |

|

≥ 38.5 |

|

|

AVPU score |

|

|

|

Alert |

Reaction to voice |

Reaction to pain |

Unresponsive |

Supplement Table 5. Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock, Modified Early Warning Score, quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score for the outcomes in variceal bleeding group.

AIMS65: Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; CRS: complete Rockall score; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score; ICU: intensive care unit; MEWS, Modified Early Warning Score; qSOFA, quick Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment.

|

Outcome and scoring system |

AUC |

95% CI |

|

|||

|

Mortality |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.75 |

0.70–0.79 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.64 |

0.59–0.70 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.75 |

0.70–0.80 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.75 |

0.70–0.80 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.60 |

0.54–0.65 |

|||

|

Rebleeding |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.64 |

0.58–0.70 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.59 |

0.53–0.65 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.57 |

0.51–0.63 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.64 |

0.58–0.69 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.56 |

0.50–0.63 |

|||

|

ICU admission |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.78 |

0.73–0.82 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.72 |

0.67–0.77 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.74 |

0.69–0.79 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.60 |

0.54–0.65 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.61 |

0.56–0.66 |

|||

|

Development of infection |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.76 |

0.71–0.80 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.68 |

0.62–0.73 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.72 |

0.67–0.77 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.62 |

0.57–0.66 |

|||

|

CRS |

0.58 |

0.52–0.63 |

|

|||

Supplement Table 6. Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock, Modified Early Warning Score, quick Sepsis Related Organ Failure Assessment, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score for the outcomes in nonvariceal bleeding group.

AIMS65: Age 65; International normalized ratio; Mental status; Shock; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; CRS: complete Rockall score; GBS: Glasgow-Blatchford score; ICU: intensive care unit; MEWS: Modified Early Warning Score; qSOFA: quick Sepsis Organ Failure Assessment.

|

Outcome and scoring system |

AUC |

95% CI |

|

|||

|

Mortality |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.81 |

0.72–0.88 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.73 |

0.64–0.81 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.63 |

0.54–0.72 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.63 |

0.54–0.72 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.77 |

0.68–0.84 |

|||

|

Rebleeding |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.70 |

0.55–0.83 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.54 |

0.38–0.69 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.54 |

0.39–0.69 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.52 |

0.32–0.67 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.63 |

0.48–0.77 |

|||

|

ICU admission |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.82 |

0.73–0.88 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.80 |

0.72–0.87 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.78 |

0.69–0.85 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.65 |

0.55–0.73 |

|||

|

|

CRS |

0.61 |

0.51–0.70 |

|||

|

Development of infection |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

AIMS65 |

0.66 |

0.57–0.74 |

|||

|

|

MEWS |

0.66 |

0.58–0.74 |

|||

|

|

qSOFA |

0.62 |

0.53–0.71 |

|||

|

|

GBS |

0.61 |

0.52–0.70 |

|||

|

CRS |

0.68 |

0.55–0.73 |

|

|||

References

- 1.Moon Andrew M., Dominitz Jason A., Ioannou George N., Lowy Elliott, Beste Lauren A. Use of Antibiotics Among Patients With Cirrhosis and Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Is Associated With Reduced Mortality. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016 Nov;14(11) doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo Ming-Te, Yang Shih-Cheng, Lu Lung-Sheng, Hsu Chien-Ning, Kuo Yuan-Hung, Kuo Chung-Huang, Liang Chih-Ming, Kuo Chung-Mou, Wu Cheng-Kun, Tai Wei-Chen, Chuah Seng-Kee. Predicting risk factors for rebleeding, infections, mortality following peptic ulcer bleeding in patients with cirrhosis and the impact of antibiotics prophylaxis at different clinical stages of the disease. BMC Gastroenterology. 2015 May 20;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0289-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng Ying, Qi Xingshun, Dai Junna, Li Hongyu, Guo Xiaozhong. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015 Jan 15;8(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morsy Khairy H, Ghaliony Mohamed AA, Mohammed Hamdy S. Outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality among cirrhotic patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in upper Egypt. The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015 Jan 13;25(6) doi: 10.5152/tjg.2014.6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu Shou-Chien, Chen Chih-Yu, Weng Yi-Ming, Chen Shou-Yen, Lin Chi-Chun, Chen Jih-Chang. Comparison of 3 scoring systems to predict mortality from unstable upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014 May;32(5) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyles Thomas, Elliott Alan, Rockey Don C. A Risk Scoring System to Predict In-hospital Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis Presenting With Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2014 Sep;48(8) doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu Yao-Chun, Liou Jyh-Ming, Chung Chen-Shuan, Tseng Cheng-Hao, Lin Tzu-Ling, Chen Chieh-Chang, Wu Ming-Shiang, Wang Hsiu-Po. Early risk stratification with simple clinical parameters for cirrhotic patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010 Oct;28(8) doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrion Jean, Deltenre Pierre, De Maeght Stéphane, Ghilain Jean-Michel, Maisin Jean-Marc, Moulart Michel, Delaunoit Thierry, Verset Didier, Yeung Ralph, Schapira Michael. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis: changes and advances over the past two decades. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011 Sep;74(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svoboda Pavel, Konecny Michal, Martinek Arnost, Hrabovsky Vladimir, Prochazka Vlastimil, Ehrmann Jiri. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis patients. Biomedical Papers. 2012 Sep 01;156(3) doi: 10.5507/bp.2012.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanley Adrian J, Laine Loren, Dalton Harry R, Ngu Jing H, Schultz Michael, Abazi Roseta, Zakko Liam, Thornton Susan, Wilkinson Kelly, Khor Cristopher J L, Murray Iain A, Laursen Stig B. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017 Jan 04; doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Cara Juan G, Jiménez-Rosales Rita, Úbeda-Muñoz Margarita, de Hierro Mercedes López, de Teresa Javier, Redondo-Cerezo Eduardo. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow–Blatchford score, and Rockall score in a European series of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: performance when predicting in-hospital and delayed mortality. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 2015 Sep 07;4(3) doi: 10.1177/2050640615604779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson Marcus, Majumdar Avik, Boyapati Ray, Chung William, Worland Tom, Terbah Ryma, Wei James, Lontos Steve, Angus Peter, Vaughan Rhys. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2016 Jun;83(6) doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abougergi Marwan S., Charpentier Joseph P., Bethea Emily, Rupawala Abbas, Kheder Joan, Nompleggi Dominic, Liang Peter, Travis Anne C., Saltzman John R. A Prospective, Multicenter Study of the AIMS65 Score Compared With the Glasgow-Blatchford Score in Predicting Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2016 Jul;50(6) doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaka Elif, Yılmaz Serkan, Özgür Doğan Nurettin, Pekdemir Murat. Mark Courtney D., editor. Comparison of the Glasgow-Blatchford and AIMS65 Scoring Systems for Risk Stratification in Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014 Dec 31;22(1) doi: 10.1111/acem.12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura Shotaro, Matsumoto Takayuki, Sugimori Hiroshi, Esaki Motohiro, Kitazono Takanari, Hashizume Makoto. Emergency endoscopy for acute gastrointestinal bleeding: P rognostic value of endoscopic hemostasis and the AIMS65 score in J apanese patients. Digestive Endoscopy. 2013 Oct 29;26(3) doi: 10.1111/den.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyett Brian H., Abougergi Marwan S., Charpentier Joseph P., Kumar Navin L., Brozovic Suzana, Claggett Brian L., Travis Anne C., Saltzman John R. The AIMS65 score compared with the Glasgow-Blatchford score in predicting outcomes in upper GI bleeding. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2013 Apr;77(4) doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozkurt Seyran, Köse Ataman, Arslan Engin Deniz, Erdoğan Semra, Üçbilek Enver, Çevik İbrahim, Ayrık Cüneyt, Sezgin Orhan. Validity of modified early warning, Glasgow Blatchford, and pre-endoscopic Rockall scores in predicting prognosis of patients presenting to emergency department with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2015 Dec;23(1) doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0194-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vivas S, Rodriguez M, Palacio MA, Linares A, Alonso JL, Rodrigo L. Presence of Bacterial Infection in Bleeding Cirrhotic Patients Is Independently Associated with Early Mortality and Failure to Control Bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2001 Dec;46(12) doi: 10.1023/a:1012739815892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goulis John, Armonis Anastasios, Patch David, Sabin Caroline, Greenslade Lynda, Burroughs Andrew K. Bacterial infection is independently associated with failure to control bleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1998 May;27(5) doi: 10.1002/hep.510270504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernard Brigitte, Cadranel Jean-Francois, Valla Dominique, Escolano Sylvie, Jarlier Vincent, Opolon Pierre. Prognostic significance of bacterial infection in bleeding cirrhotic patients: A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1995 Jun;108(6) doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer Mervyn, Deutschman Clifford S., Seymour Christopher Warren, Shankar-Hari Manu, Annane Djillali, Bauer Michael, Bellomo Rinaldo, Bernard Gordon R., Chiche Jean-Daniel, Coopersmith Craig M., Hotchkiss Richard S., Levy Mitchell M., Marshall John C., Martin Greg S., Opal Steven M., Rubenfeld Gordon D., van der Poll Tom, Vincent Jean-Louis, Angus Derek C. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016 Feb 23;315(8) doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CHOLONGITAS E., PAPATHEODORIDIS G. V., VANGELI M., TERRENI N., PATCH D., BURROUGHS A. K. Systematic review: the model for end-stage liver disease - should it replace Child-Pugh's classification for assessing prognosis in cirrhosis? Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005 Dec;22(11-12) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saltzman John R., Tabak Ying P., Hyett Brian H., Sun Xiaowu, Travis Anne C., Johannes Richard S. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2011 Dec;74(6) doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subbe C.P. Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001 Oct 01;94(10) doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.10.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B, Northfield T C. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996 Mar 01;38(3) doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blatchford Oliver, Murray William R, Blatchford Mary. A risk score to predict need for treatment for uppergastrointestinal haemorrhage. The Lancet. 2000 Oct;356(9238) doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeLong Elizabeth R., DeLong David M., Clarke-Pearson Daniel L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988 Sep;44(3) doi: 10.2307/2531595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boonpongmanee Somprak, Fleischer David E, Pezzullo John C, Collier Kevin, Mayoral William, Al-Kawas Firas, Chutkan Robynne, Lewis James H, Tio Thian L, Benjamin Stanley B. The frequency of peptic ulcer as a cause of upper-GI bleeding is exaggerated. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2004 Jun;59(7) doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wollenman Casey S., Chason Rebecca, Reisch Joan S., Rockey Don C. Impact of Ethnicity in Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2014 Apr;48(4) doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunt RH, Malfertheiner P, Yeomans ND, Hawkey CJ, Howden CW. Critical issues in the pathophysiology and management of peptic ulcer disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995 Jul;7(7) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallas J., Lauritsen J., Villadsen H. Dalsgard, Gram L. Freng. Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding, Identifying High-Risk Groups by Excess Risk Estimates. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1995 Jan;30(5) doi: 10.3109/00365529509093304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Shih-Cheng, Wu Keng-Liang, Wang Jing-Hung, Lee Chen-Hsiang, Kuo Yuan-Hung, Tai Wei-Chen, Chen Chien-Hung, Chiou Shue-Shian, Lu Sheng-Nan, Hu Tsung-Hui, Changchien Chi-Sin, Chuah Seng-Kee. The effect of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer bleeding after endoscopic interventions. Hepatology International. 2012 Jun 22;7(1) doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9378-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Budimir Ivan, Gradišer Marina, Nikolić Marko, Baršić Neven, Ljubičić Neven, Kralj Dominik, Budimir jr. Ivan. Glasgow Blatchford, pre-endoscopic Rockall and AIMS65 scores show no difference in predicting rebleeding rate and mortality in variceal bleeding. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016 Jun 29;51(11) doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1200138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammad Asmaa N., Morsy Khairy H., Ali Moustafa A. Variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients: What is the best prognostic score? The Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology. 2016 Oct 25;27(5) doi: 10.5152/tjg.2016.16250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laursen Stig Borbjerg, Hansen Jane Møller, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell Ove B. The Glasgow Blatchford Score Is the Most Accurate Assessment of Patients With Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012 Oct;10(10) doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espinoza-Ríos Jorge, Sánchez Victor Aguilar, Paredes Eduar Alban Bravo, Valdivia José Pinto, Huerta-Mercado Tenorio Jorge. Comparison between Glascow-Blatchford, Rockall and AIMS65 scores in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a hospital in Lima, Peru. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2016 Apr-Jun;36(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong Min, Chen Wan Jun, Lu Xiao Ye, Qian Jie, Zhu Chang Qing. Comparison of three scoring systems in predicting clinical outcomes in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective observational study. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2016 Dec;17(12) doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motola-Kuba Miguel, Escobedo-Arzate Angélica, Tellez-Avila Félix, Altamirano José, Aguilar-Olivos Nancy, González-Angulo Alberto, Zamarripa-Dorsey Felipe, Uribe Misael, Chávez-Tapia Norberto C. Validation of prognostic scores for clinical outcomes in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding. Ann Hepatol. 2016 Nov-Dec;15(6) doi: 10.5604/16652681.1222107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chavez-Tapia Norberto C, Barrientos-Gutierrez Tonatiuh, Tellez-Avila Felix I, Soares-Weiser Karla, Uribe Misael. Antibiotic prophylaxis for cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 Sep 08; doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd002907.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]