Abstract

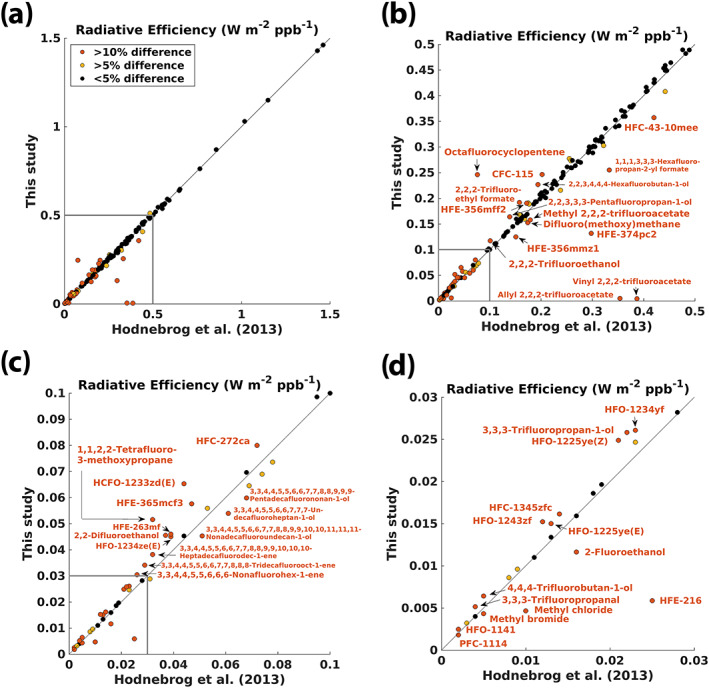

Human activity has led to increased atmospheric concentrations of many gases, including halocarbons, and may lead to emissions of many more gases. Many of these gases are, on a per molecule basis, powerful greenhouse gases, although at present‐day concentrations their climate effect is in the so‐called weak limit (i.e., their effect scales linearly with concentration). We published a comprehensive review of the radiative efficiencies (RE) and global warming potentials (GWP) for around 200 such compounds in 2013 (Hodnebrog et al., 2013, https://doi.org/10.1002/rog.20013). Here we present updated RE and GWP values for compounds where experimental infrared absorption spectra are available. Updated numbers are based on a revised “Pinnock curve”, which gives RE as a function of wave number, and now also accounts for stratospheric temperature adjustment (Shine & Myhre, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001951). Further updates include the implementation of around 500 absorption spectra additional to those in the 2013 review and new atmospheric lifetimes from the literature (mainly from WMO (2019)). In total, values for 60 of the compounds previously assessed are based on additional absorption spectra, and 42 compounds have REs which differ by >10% from our previous assessment. New RE calculations are presented for more than 400 compounds in addition to the previously assessed compounds, and GWP calculations are presented for a total of around 250 compounds. Present‐day radiative forcing due to halocarbons and other weak absorbers is 0.38 [0.33–0.43] W m−2, compared to 0.36 [0.32–0.40] W m−2 in IPCC AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.018), which is about 18% of the current CO2 forcing.

Keywords: radiative efficiencies, global warming potentials, halocarbons

Key Points

Radiative efficiencies are reassessed for more than 600 compounds and global warming potentials calculated for around 250 of these

Forty‐two compounds have >10% different radiative efficiency compared to a comprehensive review in 2013

Present‐day radiative forcing due to halocarbons and other weak absorbers is 0.38 [0.33–0.43] W m−2, which is ~18% of the CO2 forcing

1. Introduction

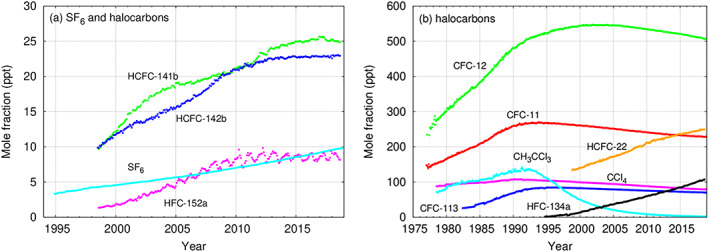

Anthropogenic forcing of climate change is one of the most important challenges facing humanity. The largest contributor to radiative forcing of climate change is the increased levels of greenhouse gases such as CO2, N2O, CH4, and halocarbons and related compounds. While many halocarbons, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), are known for depleting stratospheric ozone (Molina & Rowland, 1974; WMO, 2019), they are also powerful greenhouse gases. Despite the phase‐out of several halocarbons through the Montreal Protocol from 1987 and its amendments and adjustments, halocarbons still make an important contribution to radiative forcing of climate change because many have long atmospheric lifetimes. Furthermore, the concentrations of some replacement compounds, such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are rising. More specifically, Figure 1 (WMO/GAW, 2019) shows that HCFC‐22 has recently become the second most abundant compound (of the greenhouse gases with only anthropogenic sources) after CFC‐12. HFC‐134a has, in only 20 years, increased from very low abundance to become the fourth most abundant halocarbon. Emissions of HFCs, perfluorocarbons, SF6, and NF3 are included in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Controls on emissions of HFCs, in addition to CFCs and HCFCs, are included in the 2016 Kigali Agreement to the Montreal Protocol (see discussion in Kochanov et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Atmospheric abundances of important halocarbons (and SF6), separated into (a) lower and (b) higher mole fractions and based on observations from a number of stations (from WMO/GAW, 2019). The plots are based on the data submitted to the World Data Center for Greenhouse Gases supported by the Japan Meteorological Agency by laboratories participating in the GAW program.

Differences in the intensity and wavelength of infrared (IR) absorption bands lead to distinct radiative forcing efficiencies of various gases. Radiative efficiency (RE) is a measure of the radiative forcing for a unit change in the atmospheric concentration of a gas, and for halocarbons and related compounds is usually reported in units of W m−2 ppb−1. To provide policy makers with guidance on the relative effectiveness of actions limiting the emissions of different gases, metrics have been developed to place the impact of emissions of different gases on a common scale. The most widely used metric is the global warming potential (GWP) with a 100‐year time horizon (hereafter GWP(100)), which is based on the time‐integrated radiative forcing due to a pulse emission of a unit mass of gas, normalized by the reference gas CO2 and was introduced in the first assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 1990) (see section 2.5).

In 2013 we reviewed the literature data and provided a comprehensive and self‐consistent set of new calculations of REs and GWPs for halocarbons and related compounds (Hodnebrog et al., 2013, hereafter referred to as H2013). Unlike the major greenhouse gases, current atmospheric concentrations of these compounds are low enough for the forcing to scale almost linearly with abundance, and we will therefore refer to these compounds as weak atmospheric absorbers. Adopting a common method for calculating REs and GWPs provides a more consistent approach to comparing metrics between different compounds than if these metrics are taken from studies that used different methodologies. Our results were incorporated by the IPCC into the fifth assessment report (AR5) (Myhre et al., 2013) and, as a result, they are now used in national and international agreements. The UNFCCC adopted AR5 values for reporting emissions under the Paris Agreement and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) uses GWP values from AR5 in its reports. To ensure that climate policy decisions are based on the latest scientific data, it is important to periodically review and update the assessments. Additional infrared absorption spectra and refinements in estimations of the atmospheric lifetimes of halocarbons and other compounds have become available since our last review. Specifically, we have considered and included absorption spectra given as supporting information to published papers, and from the HITRAN2016 (Kochanov et al., 2019) and PNNL (Sharpe et al., 2004) databases. Atmospheric lifetimes have recently been updated in WMO (2019) and these estimates have been used here. The provision of GWP(100) values in this paper, and in H2013, should not be seen as an endorsement of that metric, as the choice of metric depends on the policy context (Myhre et al., 2013); the RE and lifetime values presented here can be used to derive values for alternative emission metrics.

We have updated and extended our previous assessment of REs and GWPs for halocarbons and other weak atmospheric absorbers. Updates are based on new absorption spectra for 60 compounds considered in our previous review, the latest estimates of atmospheric lifetimes, and an update to the RE calculation method. The review has been extended to include around 440 additional compounds to bring the total number of compounds considered to more than 600. Included are several isomeric species which have identical empirical formulae but are structurally and spectrally distinct. Therefore, there is no need to consider isomeric compounds together within the context of this review. The radiative forcing contributions of the 40 most abundant halocarbons and related compounds in the atmosphere are estimated. The present work is the most comprehensive review of the radiative efficiencies and GWPs of halogenated compounds performed to date.

2. Data and Method

2.1. Absorption Cross Sections

In addition to the experimental spectra included in H2013 we have included, either in the main or supporting information, all IR absorption spectra available from the HITRAN2016 (Gordon et al., 2017; Kochanov et al., 2019) and PNNL (Sharpe et al., 2004) databases. The vast majority of spectra from PNNL are also available in HITRAN2016 and we have only included data from one of the databases to avoid overlap. The main sources of experimental infrared absorption cross sections in H2013 were the Ford Motor Company (e.g., Sihra et al., 2001), the Spectroscopy and Warming potentials of Atmospheric Greenhouse Gases project (Ballard et al., 2000b; Highwood & Shine, 2000), HITRAN‐2008 (Rothman et al., 2009) and GEISA‐2009 (Jacquinet‐Husson et al., 2011) databases, and data provided by authors of published papers (e.g., Imasu et al., 1995). Several of the spectra used in H2013 were provided in the supporting information and later included in the HITRAN2016 and GEISA‐2015 (Jacquinet‐Husson et al., 2016) databases. Many publications now make available their measured absorption cross sections as supporting information. Since spectra provided as supporting information are typically not in a standardized data format and need to be converted, we could only carry out RE calculations for a limited number of these supporting information spectra, and we have prioritized the 40 most atmospherically abundant compounds. For other studies the reported integrated absorption cross section and RE value, if available, are listed (Tables S1‐S20).

As in H2013, each of the available spectra has been evaluated and if several spectra from the same laboratory group exist, we only use the latest published spectrum. For example, spectra from Sihra et al. (2001) supersede those from Pinnock et al. (1995) and Christidis et al. (1997) due to improvements in the methodology of the Ford laboratory measurements. When more than one spectrum was available from a source, the spectrum that was recorded nearest room temperature and atmospheric pressure was used (see section 2.2 for a discussion of the temperature dependence of cross sections). The choices of spectra to be used in RE calculations have been explained for each group of compounds in the supporting information (Texts S1–S20).

In contrast to H2013, we only consider experimental absorption cross sections that are measured in a laboratory. As a result, 44 of the compounds included in H2013 have been omitted here because experimental spectra are not available, while nine of the compounds that only had calculated spectra in H2013 have been updated with RE values based on experimental spectra. Calculated IR spectra have been published for a vast number of compounds (e.g., Davila et al., 2017; Papanastasiou et al., 2018), with some studies including thousands of compounds (Betowski et al., 2016; Kazakov et al., 2012; McLinden et al., 2014) but these have a considerably larger uncertainty than experimental spectra (see Table 1 of H2013).

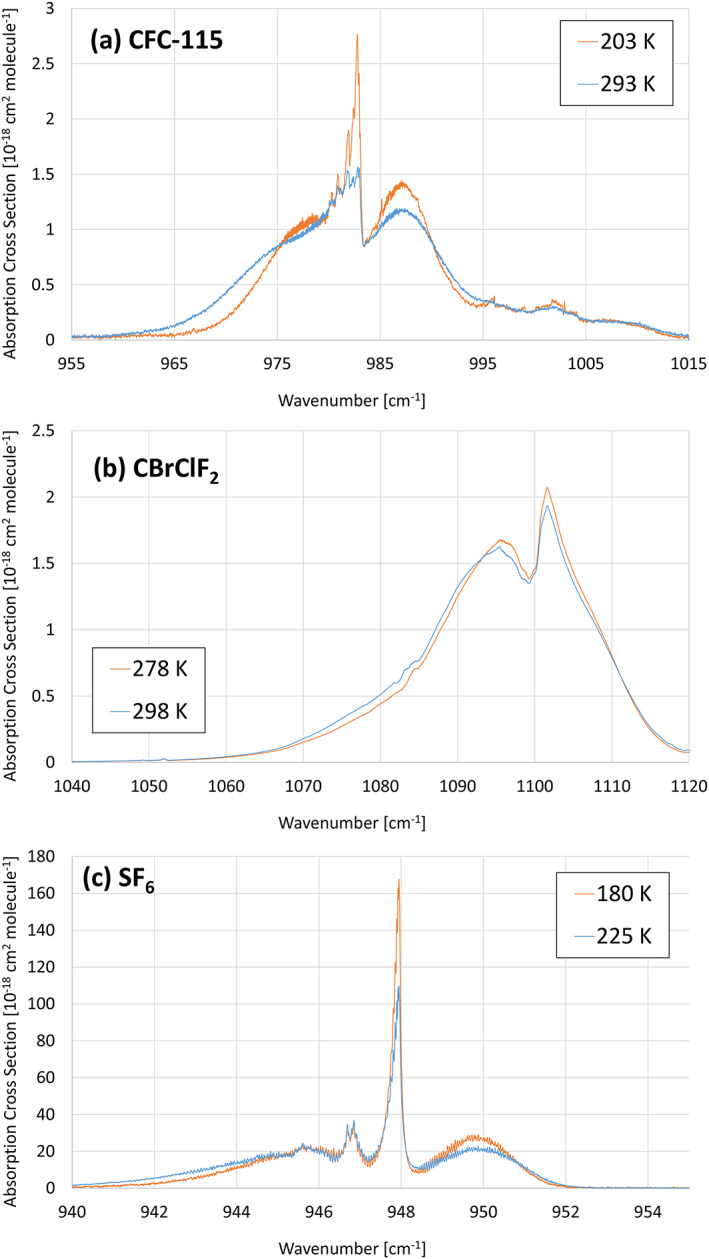

2.2. Temperature Dependence of Cross Sections

Although absorption cross sections are temperature dependent, integrated absorption cross sections show little dependence on temperature. The origin of the temperature dependence of absorption cross sections is the strong dependence of rotational states on temperature. Consequently, spectral bands are generally broader and have a lower peak intensity when observed at higher temperatures. This effect is illustrated in Figure 2 for a range of compound types (CFC, halon and sulfur‐containing species), temperature range and pressure. The effect is noticeable even for the 20 K temperature difference illustrated in Figure 2 for CBrClF2. These small changes in band structure have a negligible effect on calculated REs, and hence GWPs.

Figure 2.

Effect of temperature on band shape. (a) CFC‐115: T = 203 K, p = 0 Torr; T = 298 K, p = 0 Torr (Massie et al., 1991; McDaniel et al., 1991). (b) CBrClF2: T = 273 K, p = 760 Torr; T = 293 K, p = 760 Torr (Sharpe et al., 2004). (c) SF6: T = 180 K, p = 75 Torr; T = 225 K, p = 78 Torr (referred to as Varanasi, private communication, 2000, in HITRAN).

However, when molecules exist in two or more distinct conformational forms, the possibility of significant temperature dependence of the integrated cross section exists (Godin et al., 2019). For example, the absorption spectra for CFC‐114 reported by McDaniel et al. (1991) indicate that there are bands within the spectrum that show relatively strong positive temperature dependence, bands that show a weak negative temperature dependence, and bands that are not temperature dependent. These observations can be rationalized in terms of the temperature dependence of the populations of the two different conformers of CFC‐114. However, the integrated cross sections of most molecules show little temperature dependence, and for consistency, we have used spectra obtained at ambient temperatures, where the experimental uncertainties are typically smallest.

2.3. Radiative Efficiency

In H2013, a common method was used to calculate the RE for most gases. This employed the “Pinnock curve” (Pinnock et al., 1995) where the RE as a function of wave number was calculated for a weak absorber absorbing equally at all wave numbers. Multiplying this curve by the absorption cross section of a given gas yields its RE. In H2013 the Pinnock curve was updated (Figure 3, blue line), most notably by increasing its spectral resolution from 10 to 1 cm−1 using the Oslo Line‐By‐Line (OLBL) radiative transfer model run at 0.02 cm−1 resolution (note that there was a typo in the caption of Figure 6 in H2013, wrongly stating a resolution of 0.2 cm−1); the updated calculations also used more refined atmospheric profiles of temperature, cloudiness and greenhouse gas concentrations. For instance, the atmospheric representation was expanded from one global mean profile to two profiles, one for the tropics and one for the extratropics, and the inclusion of refined cloud profiles led to weaker RE in the 800–1,200 cm−1 region (see sections 2.3 and 3.3.1 of H2013 for details). The Pinnock et al. (1995) method, and the H2013 update, yield the instantaneous RE (i.e., the radiative efficiency in the absence of stratospheric temperature adjustment). Since the RE, which includes this adjustment, provides a more accurate representation of a gas's impact on surface temperature, H2013 incorporated a correction to account for this. For most gases, the instantaneous RE was simply increased by 10%. For several gases (CFC‐11, CFC‐12, HFC‐41, and PFC‐14) the correction was explicitly calculated using OLBL, either because of the absolute importance of that gas or because, in the case of HFC‐41, it was known that the RE is less than its instantaneous value. However, this approach was somewhat ad hoc and may not have been applicable to all gases.

Figure 3.

Instantaneous radiative forcing (IRF) efficiency (for a 0–1 ppb increase in mixing ratio) per unit cross section compared between the previous (Hodnebrog et al., 2013) and updated (Shine & Myhre, 2020) results from the Oslo line‐by‐line (OLBL) radiative transfer model run at 0.02 cm−1 spectral resolution. Also shown is the new radiative forcing (RF) efficiency where the effect of stratospheric temperature adjustment per unit cross section, based on 10 cm−1 narrow band model (NBM) simulations (Shine & Myhre, 2020), have been used to modify the OLBL curve. The curves have been averaged to 10 cm−1 spectral resolution in the plot, to improve readability, but RE calculations in this paper have been made using a 1 cm−1 version of the RF efficiency curve (as provided in the supporting information of Shine and Myhre, 2020).

Shine and Myhre (2020) have incorporated stratospheric temperature adjustment into the Pinnock curve for the first time, by calculating the impact of absorption by a gas at a given wave number on stratospheric temperatures (Figure 3, red vs. purple line). The calculation of this adjustment is computationally intensive, as the RE due to absorption by a gas at a given wave number occurs not only at that wave number (as in the case of instantaneous RE) but now depends on the emission by gases (mostly CO2, H2O, and O3) at all other wave numbers. Because of this, Shine and Myhre (2020) calculated the effect of adjustment using a narrow‐band (10 cm−1) radiation code, and applied this to updated instantaneous RE calculations using OLBL (which included an improved representation of the water vapor continuum and some changes to the representation of clouds). The new method reproduced detailed calculations for a range of gases (including HFC‐41 and CFC‐11) to better than 1.5%. Although more complicated in its derivation, it is no more complicated than the original Pinnock method in its application. This new method (which also requires the use of the lifetime correction described in section 2.4) is applied to all gases here and hence improves the relative consistency of derived REs.

2.4. Atmospheric Lifetimes and Lifetime Correction

The atmospheric lifetime of a compound is required for calculations of GWPs and Global Temperature‐change Potentials (GTPs) (see section 2.5). The RE value obtained from the method described in section 2.3 assumes the compound is well‐mixed in the atmosphere. Most of the compounds included in this study have a nonuniform vertical and horizontal distribution in the atmosphere, and the lifetime can be used to correct for that. Here we use the method presented in H2013 (their section 3.3.4), where two approximations are given depending on the primary loss mechanism of the compound. One approximation is used for compounds primarily being lost through photolysis in the stratosphere: the fractional correction f to the RE of f(τ) = 1 − 0.1826τ−0.3339 is applicable for lifetimes τ of 10 < τ < 104 years. Another approximation is used for compounds primarily lost through reaction with OH in the troposphere: , where a = 2.962, b = 0.9312, c = 2.994, d = 0.9302, and is applicable for 10−4 < τ < 104 years. The lifetime corrections for very short‐lived compounds should be treated as particularly approximate, as the correction depends on where the emissions take place. Excepted from these approximations are CFC‐11, CFC‐12, and Halon‐1211 because explicit LBL calculations were made in H2013 (see their section 3.3.3) to derive factors to account for non‐uniform mixing. The derived factors were 0.927, 0.970, and 0.937, respectively, and are used here in the RE calculations for these compounds. These factors are less than one, despite being quite long‐lived compounds, because of stratospheric loss due to photolysis.

The recent WMO (2019) report gives the most up‐to‐date and complete overview of atmospheric lifetimes of halocarbons and related compounds, and we rely on these estimates. Explanations and sources for the lifetime estimates in WMO (2019) are given for each compound in their Chapter 1.2 and Table A‐1. For some compounds that do not have a lifetime estimate in WMO (2019), lifetime estimates have been taken from previous literature and sometimes as an average across different estimates if more studies exist (see Tables S1–S20 for references to lifetime estimates). For several compounds, we are not aware of any estimates of lifetimes; for these we only present REs assuming a constant horizontal and vertical distribution in the atmosphere, and no estimates of GWPs can be given.

2.5. Description of Metrics

The most widely used emission metric in climate policy is the GWP. It was introduced by IPCC (1990) where values for three time horizons (20, 100, and 500 years) were given. The GWP values were updated in following assessment reports. GWP has been widely adopted in climate policies, and the Kyoto Protocol adopted GWPs for a time horizon of 100 years as its metric for implementing a multigas approach. At UNFCCC COP24 it was decided to use GWP(100) for reporting national emissions to the Paris Agreement, while parties may in addition use other metrics (e.g., global temperature change potential) to report supporting information on aggregate emissions and removals of greenhouse gases, expressed in CO2 equivalents (UNFCCC, 2019).

The GWP is based on the time‐integrated radiative forcing due to a pulse emission of a unit mass of a gas. It can be given as an absolute GWP for gas i (AGWPi) (usually in W m−2 kg−1 year) or as a dimensionless value by dividing the AGWPi by the AGWP of a reference gas, normally CO2. Thus, the GWP for gas i over a time horizon of H years is defined as

IPCC has usually presented GWPs for a time horizon (H) of 20, 100, and 500 years (although IPCC AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013) only gave GWPs for 20 and 100 years). We use updated lifetimes and RE values presented in section 3 to calculate GWPs for 20, 100, and 500 years as in H2013.

The models used to calculate the impulse response function for CO2 (Joos et al., 2013) include climate‐carbon cycle feedbacks, but usually no feedbacks are included for the non‐CO2 gases when metrics are calculated. IPCC AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013) included this feedback tentatively in the metric values (see their Table 8.7 and supporting information Table 8.SM.16), which increased the GWP(100) values by 10–20%. Gasser et al. (2017) found that accounting for climate‐carbon feedback increases the emission metrics of non‐CO2 species but, in most cases, less than indicated in AR5. They also found that when the feedback is removed for both the reference and target gas, the relative metric values are generally only modestly different compared to when the feedback is included in both (absolute metric values change more markedly); in the case of GWP(100) the differences are less than 1%. As pointed out by Gasser et al. (2017), including or excluding the climate–carbon feedback ultimately depends on the user's goal, but consistency should be ensured in either case. To resolve the consistency issue, we have excluded the climate‐carbon feedback also for CO2 by using the impulse response function for CO2 based on the Gasser et al. (2017) simple Earth system model (see their Appendix C); their model shows very good agreement with Joos et al. (2013) when the climate‐carbon feedback is included. Our documentation of input data and presentation of calculations allow for the inclusion of the climate‐carbon feedback to our results in further studies or applications, both for CO2 and the non‐CO2 compounds.

Changes to the parameters in AGWPCO2 impact all GWP values, and the GWP(100) values presented in section 3 are about 14% higher than if the old AGWPCO2 from AR5 or H2013 had been used. This is due to two changes: (i) The impulse response function for CO2 is updated as explained above and (ii) the RE of CO2 is updated using 409.8 ppm for 2019 (Butler & Montzka, 2020) and the simplified expression for CO2 RF presented in Etminan et al. (2016), which is an update of the formula from Myhre et al. (1998) used in IPCC assessment reports since TAR (IPCC, 2001). Among other improvements, Etminan et al. (2016) made more extensive use of line‐by‐line calculations compared to Myhre et al. (1998). Using the new formula, a 1 ppm change in the CO2 concentration at current (year 2019) levels of CO2 (409.8 ppm) and N2O (331.9 ppb) (Butler & Montzka, 2020) gives a radiative efficiency for CO2 of 0.012895 W m−2 ppm−1. The new AGWPCO2 values for 20, 100, and 500 year time horizons are 2.290 × 10−14, 8.064 × 10−14, and 2.694 × 10−13 W m−2 yr (kgCO2)−1, respectively. The AGWPCO2(100) value in AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013) and H2013 was about 14% higher, mainly because we updated the impulse response function (accounts for about 8% of the 14% change) and because of a higher atmospheric concentration of CO2 which lowers its RE (accounts for ~5%), and slightly because of the new formula from Etminan et al. (2016) (accounts for ~1%). Accounting for all these changes, but including the climate‐carbon feedback for CO2, as has been done in much of the prior literature, would give AGWPCO2 values which are 3%, 8%, and 13% higher for 20, 100, and 500 year time horizons, respectively.

It is worth highlighting that the impact of increasing CO2 mixing ratios on GWP values is the net result of two opposing effects. First, many CO2 absorption features are saturated, or close to saturation, and hence the RE of CO2 decreases as its mixing ratio increases. Second, the fraction of CO2 remaining in the atmosphere (measured by the impulse response function) increases with CO2 mixing ratio (see Figure 8.31 in Myhre et al., 2013). The first effect decreases AGWPCO2 while the second effect increases AGWPCO2. Hence, GWP calculations for optically thin gases which are defined as AGWPX/AGWPCO2 will change with CO2 mixing ratio.

An alternative, the GTP was introduced by Shine et al. (2005). It uses the change in global mean temperature following a pulse emission for a chosen point in time as the impact parameter. While GWP is a metric integrated over time, the GTP is based on the temperature change per unit emissions for a selected year, t after the pulse emission. As for the GWP, the impact of CO2 is normally used as reference:

where AGTP (K kg−1) is the absolute GTP. The GTP uses the same input as for GWP but in addition includes a temperature response function that represents the thermal inertia of the climate system. AR5 presented values for both GWP and GTP. Here we follow the method used by AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013) and H2013 for calculating GTPs, except that the impulse response function and RE for CO2 are updated as explained above and the climate response parameters are updated from Boucher and Reddy (2008) to Geoffroy et al. (2013) (as given in Appendix C of Gasser et al., 2017), which are based on an ensemble of models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 (CMIP5) (Taylor et al., 2011) and involve a lower climate sensitivity (0.88 compared to 1.1 K (W m−2)−1 in Boucher and Reddy, 2008). The new AGTPCO2 values for 20, 50, and 100 year time horizons are 5.413 × 10−16, 4.559 × 10−16, and 4.146 × 10−16 K (kgCO2)−1, respectively. Including the climate‐carbon feedback for CO2, but keeping all other parameters the same, would give AGTPCO2 values which are 5%, 8%, and 11% higher, respectively.

There continues to be a vigorous debate about the applicability of different emission metrics (e.g., Myhre et al., 2013); metric choice depends on the particular policy context in which they are applied, and the degree to which continuity of choice is important in that context (e.g., Allen et al., 2018; Cain et al., 2019; Rogelj & Schleussner, 2019). A specific development has been the suggested use of metrics that compare one‐off pulse emissions of long‐lived gases (such as CO2) with step‐changes in emissions of short‐lived species (e.g., gases with lifetimes less than a few decades), on the basis that this leads to a more informed comparison of their ultimate impact on temperature; such approaches can either adopt GWP values, but adapt their usage (Allen et al., 2016) or more directly compute the pulse‐step equivalence (W. J. Collins et al., 2019). In the context of this review, the important point is that all such metrics require the same set of inputs (RE and lifetimes).

It is important to note that the RE and GWP(100) calculations presented here only include the direct effect, while indirect effects can be important for several compounds. Some compounds, and particularly CFCs and halons, influence radiative forcing indirectly through depletion of stratospheric ozone as shown in other work (e.g., Daniel et al., 1995; WMO, 2019). The removal of organic compounds by reaction with OH in the troposphere acts as a source of ozone and prolongs the lifetime of methane, and this has been shown to be important for several hydrocarbons (W. J. Collins et al., 2002; Hodnebrog et al., 2018).

2.6. Uncertainties

An overview of estimated contributions to uncertainties associated with the radiative forcing of halocarbons was given in Table 1 of H2013. A total RE uncertainty of ~13% was estimated for compounds with lifetimes longer than about 5 years, and ~23% for compounds with lifetimes shorter than that. The much higher uncertainty for shorter‐lived compounds is caused by the difficulty of estimating nonuniform horizontal and vertical distributions in the atmosphere, which in turn are dependent on the location of emissions (see section 2.4).

Table 1 gives updated estimates of contributions to the total radiative forcing uncertainties. As in H2013, the uncertainty estimates are based on published literature and subjective judgment and we estimate the total uncertainty to be valid for a 5% to 95% (90%) confidence range. The total RF uncertainty, calculated using the root‐sum‐square (RSS) method, is ~14% and 24% for compounds with lifetimes longer and shorter than ~5 years, respectively. These total RF uncertainties are slightly higher than in H2013 and explanations are given below.

Table 1.

Estimated Contributions to the Total Radiative Forcing Uncertainty

| Source of uncertainty | Estimated contribution to total RF uncertainty | References used as basis for uncertainty estimates |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental absorption cross‐sections | ~5% | Ballard et al. (2000a),Bravo et al. (2010), and Forster et al. (2005) |

| ‐neglected far infrared bands | ~3% | |

| ‐neglected shortwave bands | ~5% | |

| Radiation scheme | ~5% | W. D. Collins et al. (2006), Forster et al. (2005), and Oreopoulos et al. (2012) |

| Clouds | ~5% | Forster et al. (2005) and Gohar et al. (2004) |

| Spectral overlap and water vapor distribution | ~3% | Forster et al. (2005), Jain et al. (2000), and Pinnock et al. (1995) |

| Surface emissivity and temperature, and atmospheric temperature | ~5% | Forster et al. (2005) |

| Tropopause level | ~5% | Forster et al. (2005),Freckleton et al. (1998), and Myhre and Stordal (1997) |

| Temporal and spatial averaging | ~1% | Freckleton et al., 1998, and Myhre and Stordal (1997) |

| Stratospheric temperature adjustment | ~2% | Forster et al. (2005), Gohar et al. (2004), and Shine and Myhre (2020) |

| Nonuniform vertical profile | ~5% for lifetimes > ~5 years, | Hodnebrog et al. (2013) and Sihra et al. (2001) |

| ~20% for lifetimes < ~5 years | ||

| Total (RSS) | ~14% for lifetimes > ~5 years | |

| ~24% for lifetimes < ~5 years |

One issue with the use of laboratory data is that it does not always cover the entire spectral range for which radiative forcing is important (see, e.g., Figure 3). For example, the PNNL measurements mostly cover the 600–6,500 cm−1 wave number range, and so their use would neglect any absorption (and hence forcing) at lower wave numbers, although in general it extends to much higher wave numbers than those in other data sets.

The uncertainty due to lack of spectral data at low wave numbers cannot be assessed for every gas in our analysis, but there is some evidence to indicate its typical size. Highwood and Shine (2000) computed the contribution of wave numbers less than 700 cm−1 to the RE for HFC‐134a and found it contributed around 2% to the forcing. Bravo et al. (2010) presented an analysis of the RE due to a set of seven perfluorocarbons. They compared the RE calculated using ab initio methods for the wave number interval 0–2,500 cm−1 with calculations for the wave number interval 700–1,400 cm−1, chosen because it coincided with the wave number range for their associated laboratory measurements. Most of the additional absorption was at wave numbers below 700 cm−1. They found that the integrated absorption cross sections and REs for the narrow range were within 2% for the lighter PFCs, but this difference increased to 10% for heavier PFCs. Since many of the measured data sets (e.g., the PNNL data) use a broader wavelength range than 700–1,400 cm−1, it is unlikely that our estimates are systematically in error by such a large amount. Nevertheless, we introduce an additional generic uncertainty to our estimates, which was not included in the analysis of H2013, of ~3% due to neglected bands (Table 1); clearly this could be systematically investigated in future work, perhaps by including ab initio calculations outside the range of measured cross sections.

Another source of uncertainty not considered in H2013 is the contribution to RE from absorption of shortwave (SW), or solar, radiation in the near‐infrared (3,000 to 14,000 cm−1). There has been renewed interest in the SW forcing due to methane (e.g., W. D. Collins et al., 2018; Etminan et al., 2016). Etminan et al. (2016) find the direct effect of methane's near‐IR bands enhances its forcing by 6% but there is an additional 9% impact via the effect of this absorption on stratospheric temperatures (and hence on longwave forcing). This contrasts with the impact of the near‐IR bands of CO2 which cause a decrease of a few percent, because much of the additional forcing is at higher altitudes. The contribution of these near‐IR bands to RE is further complicated by the fact that it depends strongly on the overlap between these bands and those of water vapor (Etminan et al., 2016), many of which are saturated for typical atmospheric paths, making generic statements difficult.

The potential impact of SW absorption is difficult to constrain for the diverse range of gases discussed here, without much more detailed study, not least because many of the experimental data sets do not extend to such high wave numbers (the PNNL data are a notable exception). For the heavier halogenated gases, the strongest fundamental and combination bands will generally be at lower wave numbers, at which SW absorption is less important (see, e.g., Bera et al., 2009). The lighter, more hydrogenated, gases, will have more significant absorption bands in the solar near‐infrared but, on the other hand, these gases are likely to be much shorter‐lived, so that their impact on stratospheric temperatures is likely to be lower. We introduce an additional uncertainty of ~5% due to the potential effect of this shortwave absorption (Table 1).

Since H2013, surface emissivity has been included as a source of uncertainty together with surface temperature and atmospheric temperature, and consequently the estimated contribution to RF uncertainty has been increased from ~3% to ~5% (Table 1). The stratospheric temperature adjustment is now based on a much more sophisticated method compared to the generic 10% increase used in H2013 (see section 2.3), and we have lowered the uncertainty contribution for this term from ~4% to ~2%. The remaining sources of uncertainties and their estimated contributions given in Table 1 are unchanged, and we refer to H2013 for detailed explanations of each term.

Uncertainties in the atmospheric lifetime of the compounds are also important for metric calculations, and since H2013, SPARC (2013) have provided recommended lifetime values and uncertainties for a range of halocarbons. Their estimates are derived using atmospheric chemistry transport and inverse modeling, and analysis of atmospheric observations and laboratory measurements. Possible uncertainty ranges for most of the compounds in SPARC (2013) have been evaluated in Velders and Daniel (2014; their Table 1) and range from ±3% to ±33% (1 standard deviation), depending on the compound; they are typically in the range from ±15% to ±20% (or ±25% to ±33% when converted from 1 standard deviation to 5–95% (90%) confidence range). However, Velders and Daniel (2014) point out that the possible uncertainty range is likely an overestimation of the true uncertainty and the most likely range, given for some of the compounds, is substantially lower (±12% to ±20% when converted from 1 standard deviation to 5–95% (90%) confidence range).

GWP uncertainties are affected by uncertainties in the compound's lifetime, RE and the AGWPCO2, and uncertainties in GWP and/or GTP have been investigated in previous studies (Boucher, 2012; Hodnebrog et al., 2013; Olivié & Peters, 2013; Reisinger et al., 2010; Velders & Daniel, 2014; Wuebbles et al., 1995). H2013 (see their section 3.6.4) estimated GWP(100) uncertainties of ±38% and ±34% (5–95% (90%) confidence) for CFC‐11 and HFC‐134a, respectively. GWP(100) uncertainties for six HFCs in WMO (2015; their Tables 5 and 6) were approximately in the range 30–50%, which is similar to the GWP(100) uncertainties for several ozone‐depleting substances given in Velders and Daniel (2014) (their Table 4). We estimate that the uncertainties given in H2013, WMO (2015) and Velders and Daniel (2014) (approximately in the range 30–50%) are similar for the GWP(100) values calculated here and are probably also representative for most other halocarbons with similar or longer lifetimes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Updated Spectra, REs, and GWPs for the Most Abundant Halocarbons and Related Compounds

This section broadly follows the structure of section 4.1 in H2013, where absorption cross sections and radiative efficiency estimates in the literature were reviewed and new RE and GWP calculations were presented. However, we limit this section to only include studies and spectra that were not included in H2013, and only to the 40 most abundant halocarbons presented in Table 7 of Meinshausen et al. (2017) (see section 3.3 for other compounds). Also, only experimental spectra are used as a basis for our calculations here, unlike H2013 which included RE and GWP calculations for some compounds where only calculated spectra existed. In cases where spectra have been measured at different temperatures, we have used the spectra closest to room temperature (see section 2.2 for a discussion of temperature dependence of cross sections). All REs are given for all‐sky and with stratospheric temperature adjustment included (see section 2.3). The lifetime correction method from H2013, to account for a nonhomogeneous vertical and horizontal distribution in the atmosphere, has been applied to the calculated REs (see section 2.4).

Table 2 lists absorption cross sections that are new since H2013 and Tables S1–S6 in the supporting information list all (to the best of our knowledge) absorption cross sections and reported RE values from the literature. Tables S1–S6 also include calculations using the Pinnock curve from H2013 for easier identification of possible changes in RE that are due to the updated Pinnock curve from Shine and Myhre (2020). We have followed the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, IUPAC, naming scheme and included the unique Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number, CASRN, for each compound listed in the tables. Table 3 presents updated atmospheric lifetimes, REs, and GWP(100) values and discussions of the results are given below for each group of compounds. RE values with more significant figures, needed to reproduce the GWP(100) values, are given in the supporting information.

Table 2.

Integrated Infrared Absorption Cross‐Section Updates (S) Since the H2013 Review for the 40 Most Abundant Halocarbons and Related Compounds in the Atmosphere

| Name | CASRN | Identifier | Formula a | T (K) | Wn. range (cm−1) | S b | Reference | Database c | New d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorofluorocarbons | |||||||||

| Trichlorofluoromethane | 75‐69‐4 | CFC‐11 | CCl3F | 298 | 570–3,000 | 10.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Dichlorodifluoromethane | 75‐71‐8 | CFC‐12 | CCl2F2 | 294 | 800–1,270 | 13.5 | Harrison ( 2015a ) | H16 | S |

| 296 | 600–3,000 | 13.9 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S | ||||

| 1,1,2‐Trichloro‐1,2,2‐trifluoroethane | 76‐13‐1 | CFC‐113 | CCl2FCClF2 | 298 | 620–3,000 | 14.6 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,2‐Dichloro‐1,1,2,2‐tetrafluoroethane | 76‐14‐2 | CFC‐114 | CClF2CClF2 | 298 | 600–3,000 | 17.4 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1‐Chloro‐1,1,2,2,2‐pentafluoroethane | 76‐15‐3 | CFC‐115 | CClF2CF3 | 296 | 946–1,368 | 11.9 | Totterdill et al. ( 2016 ) | B | |

| 296 | 525–3,000 | 20.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S | ||||

|

Hydrochlorofluorocarbons | |||||||||

| Chlorodifluoromethane | 75‐45‐6 | HCFC‐22 | CHClF2 | 295 | 730–1,380 | 10.5 | Harrison ( 2016 ) | H16 | S |

| 296 | 550–3,000 | 10.8 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S | ||||

| 1,1‐Dichloro‐1‐fluoroethane | 1717‐00‐6 | HCFC‐141b | CH3CCl2F | 295 | 705–1,280 | Harrison (2019) | L | ||

| 283 | 570–1,470 | 8.0 | Le Bris et al. ( 2012 ) | S | |||||

| 298 | 550–3,000 | 8.4 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

| 1‐Chloro‐1,1‐difluoroethane | 75‐68‐3 | HCFC‐142b | CH3CClF2 | 283 | 650–1,500 | 10.7 | Le Bris and Strong ( 2010 ) | H16 | S |

| 298 | 600–3,000 | 11.2 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

|

Hydrofluorocarbons | |||||||||

| Trifluoromethane | 75‐46‐7 | HFC‐23 | CHF3 | 294 | 950–1,500 | 12.3 | Harrison ( 2013 ) | H16 | S |

| 296 | 600–3,000 | 12.7 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S | ||||

| Difluoromethane | 75‐10‐5 | HFC‐32 | CH2F2 | 298 | 510–3,000 | 7.0 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,1,1,2,2‐Pentafluoroethane | 354‐33‐6 | HFC‐125 | CHF2CF3 | 298 | 510–3,000 | 17.4 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,1,1,2‐Tetrafluoroethane | 811‐97‐2 | HFC‐134a | CH2FCF3 | 296 | 750–1,600 | 13.2 | Harrison (2015b) | H16 | S |

| 296 | 600–3,000 | 14.2 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S | ||||

| 1,1,1‐Trifluoroethane | 420‐46‐2 | HFC‐143a | CH3CF3 | 296 | 570–1,500 | 13.8 | Le Bris and Graham ( 2015 ) | H16 | B |

| 298 | 500–3,000 | 13.9 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

| 1,1‐Difluoroethane | 75‐37‐6 | HFC‐152a | CH3CHF2 | 298 | 525–3,000 | 8.0 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,1,1,2,3,3,3‐Heptafluoropropane | 431‐89‐0 | HFC‐227ea | CF3CHFCF3 | 298 | 500–3,000 | 25.3 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,1,1,2,2,3,4,5,5,5‐Decafluoropentane | 138495‐42‐8 | HFC‐43‐10mee | CF3CHFCHFCF2CF3 | 305 | 550–1,600 | 30.1 | Le Bris et al. ( 2018 ) | B | |

| 298 | 500–3,000 | 30.4 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

|

Chlorocarbons and Hydrochlorocarbons | |||||||||

| 1,1,1‐Trichloroethane | 71‐55‐6 | Methyl chloroform | CH3CCl3 | 298 | 500–3,000 | 5.3 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Tetrachloromethane | 56‐23‐5 | Carbon tetrachloride | CCl4 | 296 | 700–860 | 6.7 | Harrison et al. (2017) | H16 | S |

| 295–8 | 730–825 | 6.3 | Wallington et al. ( 2016 ) | B | |||||

| 298 | 730–825 | 6.4 | Sharpe et al. (2004) | P | L | ||||

| Chloromethane | 74‐87‐3 | Methyl chloride | CH3Cl | 295–8 | 660–1,620 | 0.8 | Wallington et al. ( 2016 ) | B | |

| 296 | 600–3000 | 1.3 | Sharpe et al. (2004) | P | S | ||||

| Dichloromethane | 75‐09‐2 | Methylene chloride | CH2Cl2 | 295–8 | 650–1,290 | 2.6 | Wallington et al. ( 2016 ) | B | |

| 298 | 600–3,000 | 2.8 | Sharpe et al. (2004) | H16 | S | ||||

| Trichloromethane | 67‐66‐3 | Chloroform | CHCl3 | 295–8 | 720–1,245 | 4.4 | Wallington et al. ( 2016 ) | B | |

| 298 | 580–3,000 | 5.0 | Sharpe et al. (2004) | H16 | S | ||||

|

Bromocarbons, hydrobromocarbons and halons | |||||||||

| Bromomethane | 74‐83‐9 | Methyl bromide | CH3Br | 296 | 550–3,000 | 1.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | P | S |

| Bromochlorodifluoromethane | 353‐59‐3 | Halon‐1211 | CBrClF2 | 298 | 600–3,000 | 13.2 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Bromotrifluoromethane | 75‐63‐8 | Halon‐1301 | CBrF3 | 298 | 510–3,000 | 16.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| 1,2‐Dibromo‐1,1,2,2‐tetrafluoroethane | 124‐73‐2 | Halon‐2402 | CBrF2CBrF2 | 298 | 550–3,000 | 16.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

|

Fully fluorinated species | |||||||||

| Nitrogen trifluoride | 7783‐54‐2 | NF3 | 296 | 600–1,970 | 7.3 | Totterdill et al. ( 2016 ) | B | ||

| 298 | 600–3,000 | 7.2 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

| Sulfur hexafluoride | 2551‐62‐4 | SF6 | 295 | 650–2,000 | 24.0 | Kovács et al. (2017) | L | ||

| 298 | 560–3,000 | 21.2 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | ||||

| Sulfuryl fluoride | 2699‐79‐8 | SO2F2 | 298 | 500–3,000 | 14.0 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S | |

| Tetrafluoromethane | 75‐73‐0 | PFC‐14 | CF4 | 298 | 570–3,000 | 19.8 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Hexafluoroethane | 76‐16‐4 | PFC‐116 | C2F6 | 298 | 500–3,000 | 23.1 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Octafluoropropane | 76‐19‐7 | PFC‐218 | C3F8 | 298 | 600–3,000 | 27.5 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Octafluorocyclobutane | 115‐25‐3 | PFC‐C 318 | cyc (‐CF2CF2CF2CF2‐) | 298 | 550–3,000 | 21.7 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Decafluorobutane | 355‐25‐9 | PFC‐31‐10 | n‐C4F10 | 298 | 500–3,000 | 32.4 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

| Dodecafluoropentane | 678‐26‐2 | PFC‐41‐12 | n‐C5F12 | 278 | 500–3,000 | 37.3 | Sharpe et al. ( 2004 ) | H16 | S |

Note. Spectra used in the present RE calculations are indicated in bold (see Tables S1–S6 in the supporting information for a complete list of spectra used in RE calculations).

cyc, cyclic compound.

Integrated absorption cross section given in units of 10−17 cm2 molecule−1 cm−1.

Absorption cross section downloaded from database: H16, HITRAN 2016; P, PNNL.

New data since H2013: L, literature; S, spectrum; B, both.

Table 3.

Lifetimes (τ), Radiative Efficiencies and Direct Effect GWPs (Relative to CO2) for the 40 Most Abundant Halocarbons and Related Compounds in the Atmosphere

| τ (yr) | RE (W m−2 ppb−1) | GWP(100) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifier/name | Formula | CASRN | H2013 a | WMO (2019) | H2013 | This work | H2013 | This work |

| Chlorofluorocarbons | ||||||||

| CFC‐11 | CCl3F | 75‐69‐4 | 45.0 | 52.0 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 4,660 | 5,870 |

| CFC‐12 | CCl2F2 | 75‐71‐8 | 100.0 | 102.0 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 10,200 | 11,800 |

| CFC‐113 | CCl2FCClF2 | 76‐13‐1 | 85.0 | 93.0 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 5,820 | 6,900 |

| CFC‐114 | CClF2CClF2 | 76‐14‐2 | 190.0 | 189.0 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 8,590 | 9,990 |

| CFC‐115 | CClF2CF3 | 76‐15‐3 | 1020.0 | 540.0 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 7,670 | 10,200 |

|

Hydrochlorofluorocarbons | ||||||||

| HCFC‐22 | CHClF2 | 75‐45‐6 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 1,770 | 2,060 |

| HCFC‐141b | CH3CCl2F | 1717‐00‐6 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 782 | 903 |

| HCFC‐142b | CH3CClF2 | 75‐68‐3 | 17.2 | 18.0 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1,980 | 2,410 |

|

Hydrofluorocarbons | ||||||||

| HFC‐23 | CHF3 | 75‐46‐7 | 222.0 | 228.0 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 12,400 | 15,500 |

| HFC‐32 | CH2F2 | 75‐10‐5 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 677 | 809 |

| HFC‐125 | CHF2CF3 | 354‐33‐6 | 28.2 | 30.0 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 3,170 | 3,940 |

| HFC‐134a | CH2FCF3 | 811‐97‐2 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 1,300 | 1,600 |

| HFC‐143a | CH3CF3 | 420‐46‐2 | 47.1 | 51.0 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 4,800 | 6,130 |

| HFC‐152a | CH3CHF2 | 75‐37‐6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 138 | 172 |

| HFC‐227ea | CF3CHFCF3 | 431‐89‐0 | 38.9 | 36.0 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 3,350 | 3,800 |

| HFC‐236fa | CF3CH2CF3 | 690‐39‐1 | 242.0 | 213.0 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 8,060 | 9,210 |

| HFC‐245fa | CHF2CH2CF3 | 460‐73‐1 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 858 | 1,010 |

| HFC‐365mfc | CH3CF2CH2CF3 | 406‐58‐6 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 804 | 959 |

| HFC‐43‐10mee | CF3CHFCHFCF2CF3 | 138495‐42‐8 | 16.1 | 17.0 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 1,650 | 1,680 |

|

Chlorocarbons and hydrochlorocarbons | ||||||||

| 1,1,1‐Trichloroethane | CH3CCl3 | 71‐55‐6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 160 | 169 |

| Tetrachloromethane | CCl4 | 56‐23‐5 | 26.0 | 32.0 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1,730 | 2,310 |

| Chloromethane | CH3Cl | 74‐87‐3 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 12 | 6 |

| Dichloromethane | CH2Cl2 | 75‐09‐2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 9 | 12 |

| Trichloromethane | CHCl3 | 67‐66‐3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 16 | 22 |

|

Bromocarbons, hydrobromocarbons and halons | ||||||||

| Bromomethane | CH3Br | 74‐83‐9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 2 | 3 |

| Halon‐1211 | CBrClF2 | 353‐59‐3 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 1,750 | 2,030 |

| Halon‐1301 | CBrF3 | 75‐63‐8 | 65.0 | 72.0 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 6,290 | 7,600 |

| Halon‐2402 | CBrF2CBrF2 | 124‐73‐2 | 20.0 | 28.0 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1,470 | 2,280 |

|

Fully fluorinated species | ||||||||

| Nitrogen trifluoride | NF3 | 7783‐54‐2 | 500.0 | 569.0 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 16,100 | 18,500 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | SF6 | 2551‐62‐4 | 3200.0 | 3200.0 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 23,500 | 26,700 |

| Sulfuryl fluoride | SO2F2 | 2699‐79‐8 | 36.0 | 36.0 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 4,100 | 4,880 |

| PFC‐14 | CF4 | 75‐73‐0 | 50000.0 | 50000.0 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 6,630 | 7,830 |

| PFC‐116 | C2F6 | 76–16‐4 | 10000.0 | 10000.0 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 11,100 | 13,200 |

| PFC‐218 | C3F8 | 76‐19‐7 | 2600.0 | 2600.0 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 8,900 | 9,850 |

| PFC‐C‐318 | c‐C4F8 | 115‐25‐3 | 3200.0 | 3200.0 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 9,550 | 10,800 |

| PFC‐31‐10 | n‐C4F10 | 355‐25‐9 | 2600.0 | 2600.0 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 9,200 | 10,600 |

| PFC‐41‐12 | n‐C5F12 | 678‐26‐2 | 4100.0 | 4100.0 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 8,550 | 9,780 |

| PFC‐51‐14 | n‐C6F14 | 355‐42‐0 | 3100.0 | 3100.0 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 7,910 | 9,140 |

| PFC‐61‐16 | n‐C7F16 | 335‐57‐9 | 3000.0 | 3000.0 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 7,820 | 8,920 |

| PFC‐71‐18 | n‐C8F18 | 307‐34‐6 | 3000.0 | 3000.0 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 7,620 | 8,760 |

Note. Compounds where the radiative efficiencies are based on new spectra since the H2013 review are marked in bold. Recommended RE and GWP(100) values are indicated in bold. Lifetimes are taken from WMO (2019). Note that RE values with more significant digits have been used to calculate GWP(100) and that these are available in the supporting information.

Lifetimes in H2013 were from WMO (2011) except for PFC‐71‐18.

3.1.1. Chlorofluorocarbons

Since H2013, new spectra have been included for the five most‐abundant CFCs, but the RE remains unchanged for four of the compounds (Tables 2 and 3). CFC‐115 now has a much larger RE than in H2013 (0.25 compared to 0.20 W m−2 ppb−1) due to the addition of spectra from the PNNL database (Sharpe et al., 2004). In H2013, and in two out of four previous studies (Jain et al., 2000; Myhre & Stordal, 1997), the CFC‐115 spectrum used is that from McDaniel et al. (1991), which has an integrated absorption cross‐section of 1.21 × 10−16 cm2 molecule−1 cm−1 and gives an RE of 0.20 W m−2 ppb−1 in our calculations (Table S1). Recently, Totterdill et al. (2016) measured the IR absorption spectrum of CFC‐115 and performed detailed LBL radiative transfer calculations to determine its RE. Their integrated absorption spectrum of 1.19 × 10−16 cm2 molecule−1 cm−1 is in relatively good agreement with McDaniel et al. (1991) and their resulting RE of 0.21 W m−2 ppb−1 agrees well with H2013. The PNNL spectrum for CFC‐115 has a much higher integrated absorption cross section of 2.01 × 10−16 cm2 molecule−1 cm−1 and our calculations give a RE of 0.32 W m−2 ppb−1. A comparison between the McDaniel et al. (1991) and PNNL absorption spectra shows that the locations and relative strength of the main absorption bands are similar, but that the overall magnitude of the bands are higher in the PNNL spectrum (not shown). Due to the large difference between the two spectra, we have also inspected the PNNL spectra measured at different temperatures (278 and 323 K), and these have similar integrated absorption cross sections and yield similar RE values as the 296 K PNNL spectrum (Table S1), and so give no indication of error in the 296 K PNNL spectra. A fourth source for CFC‐115 spectra is Fisher et al. (1990) who report an integrated absorption cross section of 1.74 × 10−16 cm2 molecule−1 cm−1, which is higher than McDaniel et al. (1991) and lower than (but nearer to) PNNL. Reasons for the large difference between the spectra remain unknown. We have calculated our new RE value of 0.25 W m−2 ppb−1 by averaging the RE values based on the three available spectra (McDaniel et al., 1991; Sharpe et al., 2004; Totterdill et al., 2016).

The stratospheric temperature adjustment for the CFCs ranges from 9% to 12% increase of the instantaneous RE, and the generic 10% increase used in H2013 was a relatively good approximation for these compounds (Figure 4). (Note that the 10% assumption was not used for CFC‐11 and CFC‐12 in H2013.) The atmospheric lifetimes of the five CFCs have been updated based on WMO (2019) since H2013, most notably for CFC‐11 (52 vs. 45 years in H2013) and CFC‐115 (540 vs. 1,020 years in H2013). A combination of updated lifetimes, REs, and the AGWPCO2 leads to higher GWP(100) values for all five CFCs (Table 3 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Stratospheric temperature adjustment represented as the % increase of the instantaneous RE for 40 abundant compounds. The red line shows the 10% assumption used in H2013 for nearly all compounds (note that the 10% assumption was not used for CFC‐11, CFC‐12, and PFC‐14).

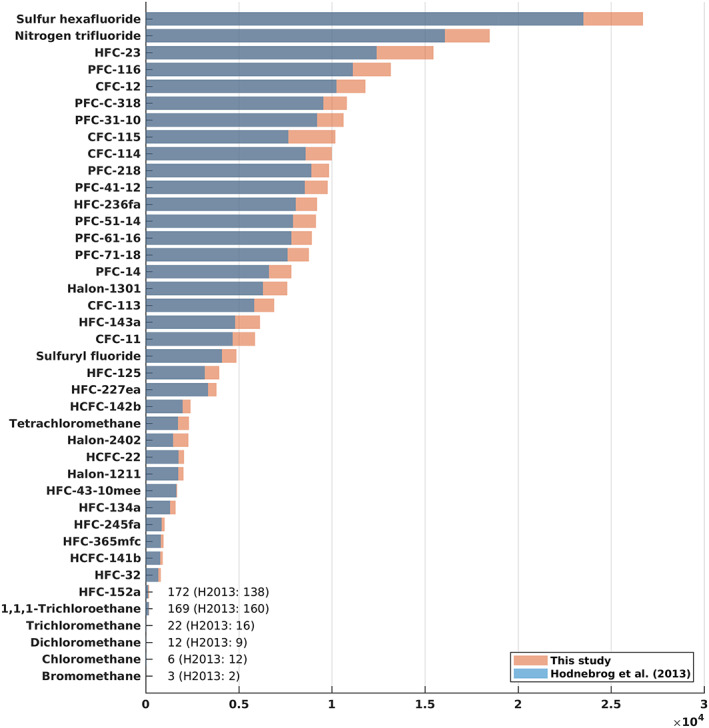

Figure 5.

GWP(100) ranking calculated in this study and from H2013 for 40 most abundant compounds. Note that only one compound (chloromethane) shows a decrease in GWP(100).

3.1.2. Hydrochlorofluorocarbons

Six new spectra have been included for the three most‐abundant HCFCs in this category, but their REs are unchanged when rounded to two decimals (Tables 2 and 3). The updated AGWPCO2, and slightly longer lifetimes for two of the compounds (HCFC‐141b and HCFC‐142b), contribute to higher GWP(100) (Tables 3 and S2 and Figure 5).

3.1.3. Hydrofluorocarbons

Since H2013, spectra have been added to eight of the 11 most‐abundant HFC compounds (Table 2) and in most cases this led to little or no change in the RE (Table 3). For HFC‐23, the two new spectra (Harrison, 2013; Sharpe et al., 2004) each have higher integrated absorption cross sections than the two spectra used in H2013 (Table S3); this leads to a higher RE for this compound (0.19 compared to 0.17 W m−2 ppb−1 in H2013). Another contributing factor is the stratospheric temperature adjustment. The RE is now 13% higher than the instantaneous RE for HFC‐23 (Figure 4), while in H2013 a generic 10% increase was used. In fact, all 11 HFC compounds have stratospheric temperature adjustments larger than 10% and most of them around 13%.

For HFC‐43‐10mee, the H2013 RE value of 0.42 W m−2 ppb−1 was not calculated using new spectra but was based on the RE given in the fourth assessment report (AR4) (Forster et al., 2007), which was again based on personal communication with D. A. Fisher in IPCC (1994). Recently, Le Bris et al. (2018) measured the absorption cross section and calculated a much lower RE of 0.36 W m−2 ppb−1 for HFC‐43‐10mee when using the method in H2013 (Table S3). They also showed that the RE calculated with their spectrum agreed very well with that calculated from the PNNL spectrum. Here, we have used the spectra from both Le Bris et al. (2018) and the PNNL database and calculated a RE of 0.36 W m−2 ppb−1 (Table 3), in excellent agreement with Le Bris et al. (2018).

Updated GWP(100) values are higher for all HFCs (Table 3 and Figure 5), and this is due to a combination of updated AGWPCO2, higher RE values for several compounds (HFC‐43‐10mee is a notable exception), and longer lifetimes for all compounds except HFC‐227ea and HFC‐236fa.

3.1.4. Chlorocarbons and Hydrochlorocarbons

Nine new spectra have been added for the five most‐abundant compounds since H2013 (Table 2). Wallington et al. (2016) made new measurements of the absorption spectra of the chloromethanes CH3Cl, CH2Cl2, CHCl3, and CCl4, and provided recommended spectra for these compounds by combining existing and new experimental data. We have used their recommended spectra to calculate REs for all four chloromethanes (see Text S4 for an explanation of the choice of spectra). The resulting RE for CCl4 of 0.17 W m−2 ppb−1 is unchanged since H2013 (Tables 3 and S4), where the spectrum from Nemtchinov and Varanasi (2003) was used. The RE of CHCl3 is lower than in H2013 (0.07 vs. 0.08 W m−2 ppb−1), where the spectrum from Vander Auwera (2000) was used. For CH3Cl and CH2Cl2, new RE calculations were not carried out for H2013 but retained from IPCC AR4 (Forster et al., 2007). Our calculations using the Wallington et al. (2016) spectrum show that the RE value of 0.03 W m−2 ppb−1 for CH2Cl2 is unchanged since H2013 when rounded to two decimal places. The RE of CH3Cl is now 0.005 W m−2 ppb−1, which is lower than the 0.01 W m−2 ppb−1 value in H2013 (which originated from AR4), but in excellent agreement with the original instantaneous RE value of 0.005 W m−2 ppb−1 from Grossman et al. (1997).

For CH3CCl3, we added the spectrum from the HITRAN 2016 database, which was again adopted from the PNNL database, and calculate a lower RE value compared to H2013 (0.06 vs. 0.07 W m−2 ppb−1) (Tables 2 and 3). The addition of the new spectrum did not change the RE, but the updated Pinnock curve and particularly the method to account for stratospheric temperature adjustment (see section 2.3) led to the lower value (Table S4). For all five compounds in this group, the stratospheric temperature adjustment is lower than the generic 10% increase used in H2013, and ranges from 0% change to a 9% increase of the instantaneous RE (Figure 4). GWP(100) values are lower for CH3Cl, and higher for the remaining four compounds (Table 3 and Figure 5). Lifetime updates for four of the compounds contribute to the changes in GWP 100‐year values.

3.1.5. Bromocarbons, Hydrobromocarbons, and Halons

Since H2013, absorption spectra from the HITRAN 2016 and PNNL databases have been included in the RE calculations for each of the four most‐abundant compounds (Table 2). Changes in RE since H2013 are negligible (<5%) for the three halons, while CH3Br shows a lower RE (0.004 vs. 0.005 W m−2 ppb−1) (Table 3), mainly because the stratospheric temperature adjustment is lower (~4%) compared to the generic 10% increase used in H2013 (Figure 4). Since H2013, lifetimes are longer for Halon‐1301 and Halon‐2402 while GWP(100) values are higher for all four compounds (Tables 3 and S5 and Figure 5).

3.1.6. Fully Fluorinated Species

For 9 of the 12 most‐abundant compounds, spectra have been added from the HITRAN 2016 database (where spectra were again adopted from the PNNL database) since H2013 (Table 2). Still, the calculated RE values for all these compounds are relatively similar to those reported in H2013 (Table 3). Sulfuryl fluoride shows the largest change of around 5%, mainly due to a slightly higher integrated absorption cross section in the new PNNL spectrum compared to that of Andersen et al. (2009), which was used in H2013 (Table S6). This is in turn partly because the PNNL spectrum also includes a weak absorption band around 550 cm−1 (not shown).

For NF3, two new spectra have been added since H2013 and the calculated RE value is now based on three different spectra (Robson et al., 2006; Sharpe et al., 2004; Totterdill et al., 2016) (Tables 2, 3, and S6). The RE value of 0.20 W m−2 ppb−1 is the same as in H2013, but the RE of 0.25 W m−2 ppb−1 presented in Totterdill et al. (2016) is substantially higher (>20%). Totterdill et al. (2016) attribute the differences to a higher integrated absorption cross section compared to Robson et al. (2006) (which was used to calculate the RE value in H2013 and AR5), but our RE calculation differs by less than 5% when using spectra from each of the two studies separately (Table S6) so this is only part of the reason. Other potential reasons include differences between the radiative transfer models, treatment of clouds, and stratospheric temperature adjustment.

The RE of SF6 has had a relatively wide range in reported literature values from 0.49 W m−2 ppb−1 (Jain et al., 2000) to 0.68 W m−2 ppb−1 (H. Zhang et al., 2011) (Table S6). Since H2013, Kovács et al. (2017) have made new measurements of the SF6 absorption spectrum and used a LBL model to calculate a RE value of 0.59 W m−2 ppb−1. Their spectrum is not included here, but their RE value is close to our calculated RE value of 0.57 W m−2 ppb−1 using spectra from the HITRAN and PNNL databases; this value was also presented in H2013 and used in AR5.

The stratospheric temperature adjustment for the fully fluorinated species ranges from 8% to 13% increase of the instantaneous RE (Figure 4). For most of these compounds, the generic 10% increase used in H2013 was a relatively good approximation for stratospheric temperature adjustment (note that the 10% assumption was not used for PFC‐14 in H2013).

GWP(100) values are higher than in H2013 for all compounds in this category (Tables 3 and S6 and Figure 5), mainly due to the updated AGWPCO2. The only lifetime change since H2013 is for NF3, which has a longer lifetime of 569 years compared to the value of 500 years that was used earlier. While we have adopted atmospheric lifetimes from WMO (2019), we note that two recent studies have calculated substantially shorter lifetimes for SF6 than the widely used estimate of 3,200 years (Ravishankara et al., 1993). If the shorter SF6 lifetimes of 1,278 [1,120–1,475] years (Kovács et al., 2017) or 850 [580–1,400] years (Ray et al., 2017) would have been used instead of 3,200 years, our GWP(100) value of 26,700 would not have been significantly affected (by less than 5%), but a shorter lifetime could be important for metric calculations using time horizons of several hundred years.

3.2. Present‐Day Radiative Forcing From Halocarbons and Related Compounds

Figure 6 shows preindustrial to present‐day radiative forcing for the halocarbons and related compounds discussed in section 3.1. RF for each group of compounds is compared against that reported in AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013—see their Table 8.2), when atmospheric concentrations from 2011 were used. We have used the atmospheric concentrations from Meinshausen et al. (2017) for 2014, but updated with 2019 observations from Butler and Montzka (2020) when available (see Table 4 for details). In the RF calculation, we use the preindustrial concentrations recommended by Meinshausen et al. (2017); these are nonzero for CH3Cl, CHCl3, CH2Cl2, CH3Br, and PFC‐14/CF4, and assumed to be zero for the remaining compounds (see Table 4 footnote).

Figure 6.

Preindustrial to present‐day radiative forcing for the different groups of compounds. Note that in AR5 (Myhre et al., 2013) (yellow bars), Halon‐1211 and Halon‐1301 were included in the CFC category.

Table 4.

Concentrations (ppt) and Radiative Forcing (mW m−2) for the 40 Most Abundant Halocarbons and Related Compounds in the Atmosphere

| Radiative forcing (mW m−2) a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifier/name | Concentrations (ppt) | H2013 REs | Updated REs | % difference |

| Chlorofluorocarbons | 246.16 | 247.47 | 1 | |

| CFC‐11 | 226.50 | 58.89 | 58.76 | 0 |

| CFC‐12 | 501.60 | 159.51 | 160.50 | 1 |

| CFC‐113 | 69.70 | 21.05 | 21.01 | 0 |

| CFC‐114 | 16.31 | 5.01 | 5.13 | 2 |

|

CFC‐115 |

8.43 | 1.70 | 2.08 | 22 |

| Hydrochlorofluorocarbons | 59.44 | 60.95 | 3 | |

| HCFC‐22 | 246.80 | 51.33 | 52.78 | 3 |

| HCFC‐141b | 24.39 | 3.95 | 3.92 | −1 |

|

HCFC‐142b |

22.00 | 4.16 | 4.25 | 2 |

| Hydrofluorocarbons | 35.61 | 37.26 | 5 | |

| HFC‐23 | 30.00 | 5.25 | 5.73 | 9 |

| HFC‐32 | 8.34 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 1 |

| HFC‐125 | 29.10 | 6.58 | 6.80 | 3 |

| HFC‐134a | 107.77 | 17.35 | 18.01 | 4 |

| HFC‐143a | 23.83 | 3.77 | 4.00 | 6 |

| HFC‐152a | 6.92 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 4 |

| HFC‐227ea | 1.01 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 6 |

| HFC‐236fa | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 3 |

| HFC‐245fa | 2.05 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1 |

| HFC‐365mfc | 0.77 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 2 |

|

HFC‐43‐10mee |

0.25 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −15 |

| Chlorocarbons and hydrochlorocarbons | 15.50 | 14.67 | −5 | |

| 1,1,1‐Trichloroethane | 1.60 | 0.11 | 0.10 | −6 |

| Tetrachloromethane | 78.50 | 13.35 | 13.04 | −2 |

| Chloromethane | 539.54 | 0.83 | 0.38 | −53 |

| Dichloromethane | 36.35 | 0.91 | 0.85 | −7 |

|

Trichloromethane |

9.90 | 0.30 | 0.29 | −6 |

| Bromocarbons, hydrobromocarbons and halons | 2.07 | 2.09 | 1 | |

| Bromomethane | 6.69 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −14 |

| Halon‐1211 | 3.25 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 2 |

| Halon‐1301 | 3.28 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0 |

|

Halon‐2402 |

0.40 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0 |

| Fully fluorinated species | 12.83 | 13.06 | 2 | |

| Nitrogen trifluoride | 1.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | 9.96 | 5.65 | 5.64 | 0 |

| Sulfuryl fluoride | 2.04 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 5 |

| PFC‐14 | 81.09 | 4.47 | 4.64 | 4 |

| PFC‐116 | 4.40 | 1.10 | 1.15 | 4 |

| PFC‐218 | 0.60 | 0.17 | 0.16 | −3 |

| PFC‐C‐318 | 1.34 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0 |

| PFC‐31‐10 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2 |

| PFC‐41‐12 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1 |

| PFC‐51‐14 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 2 |

| PFC‐61‐16 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0 |

|

PFC‐71‐18 |

0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1 |

| Total | 371.60 | 375.49 | 1.0 | |

Note. Concentrations in italics are from 2014 (Meinshausen et al., 2017) and the remaining from 2019 (Butler & Montzka, 2020). The REs used to calculate RF are both from H2013 and from this study. Note that RE values with more significant digits than given in Table 3 have been used to calculate RF for each compound and that these are available in the supporting information.

Preindustrial values are zero except for chloromethane (457 ppt), dichloromethane (6.9 ppt), trichloromethane (6 ppt), bromomethane (5.3 ppt), and PFC‐14/CF4 (34.05 ppt), see Meinshausen et al. (2017).

When using the same RE values as in AR5 (from H2013), we see that the change from 2011 to 2014/2019 concentrations has led to a decrease in radiative forcing of CFCs (Figure 6). At the same time, concentrations of the CFC replacement compounds HCFCs and HFCs have increased and this leads to stronger RF for these compound groups, most notably for HFCs with a 83% increase in the RF. In total, RF due to increasing concentrations of HCFCs and HFCs more than outweighs the decrease in RF due to declining concentrations of CFCs. For the present‐day (2014/2019) RF, nearly all compound groups show slightly higher RF when using new REs compared to using AR5 REs. The total present‐day (2014/19) RF due to halocarbons is 0.38 [0.33 to 0.43] W m−2 compared to 0.36 [0.32 to 0.40] W m−2 in AR5, and while updated RE values push present‐day RF upward (by ~4 mW m−2; green vs. purple bars in Figure 6), the main reason for the RF increase can be attributed to increased concentrations (yellow vs. green bars in Figure 6).

Table 4 shows that the main contributors to the ~4 mW m−2 increase in RF are the updated RE values for CFC‐12, HCFC‐22, and HFC‐134a. Chloromethane has the largest relative change in RF (and RE) with a 53% decrease. While its atmospheric concentration is the highest among the compounds, its high abundance is mainly due to natural sources (WMO, 2019) and its influence on anthropogenic RF is therefore much smaller than would otherwise be expected. Here we have assumed a pre‐industrial value of 457 ppt from Meinshausen et al. (2017) who used a simple budget equation for its derivation, and it should be noted that this number is associated with uncertainties due to a lack of observations. Table 4 further shows that CFC‐115 and HFC‐43‐10mee, respectively, have the second and third largest relative RF change due to new REs. While the new REs of methyl chloride and HFC‐43‐10mee are lower compared to H2013, the RE of CFC‐115 is higher (see section 3.1).

The RF of 0.38 W m−2 due to halocarbons and other weak atmospheric absorbers can be put into context by comparison with the RF due to increased CO2 concentrations. When using the simplified formula from Etminan et al. (2016), and assuming preindustrial (1750) and 2019 CO2 concentrations of 278 ppm (Myhre et al., 2013) and 409.8 ppm (Butler & Montzka, 2020), respectively (and of 270 ppb and 331.9 ppb, respectively, for N2O), the present‐day RF due to CO2 is 2.09 W m−2. Thus, the RF due to halocarbons and other weak absorbers is 18% of the RF due to increased CO2 concentrations.

3.3. Updated Spectra, REs, and GWPs for Other Weak Atmospheric Absorbers

This section has a similar structure to section 3.1 but presents and discusses lifetimes, REs, and GWP(100) values for compounds other than the 40 most abundant halocarbons and related compounds. Table 5 shows results for the compound groups included in our previous review (H2013), and brief discussions of these results are given in sections 3.3.1, 3.3.7 below. Tables S7–S13 in the supporting information provide information on how the RE numbers were derived and list previously published absorption cross sections and reported RE values from the literature. In addition to the compound groups included in H2013, we have made RE calculations for a number of other compounds, mainly based on absorption spectra from the HITRAN 2016 (Kochanov et al., 2019) and PNNL (Sharpe et al., 2004) databases. These results are presented in Tables S14–S20 and a brief discussion of these results is given in section 3.3.8 below.

Table 5.

Lifetimes (τ), Radiative Efficiencies and Direct GWPs (Relative to CO2) for Less Abundant Compounds

| RE (W m−2 ppb−1) | GWP(100) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifier/name | Formula a | CASRN | τ (yr) | H2013 | This work | H2013 | This work |

| Chlorofluorocarbons | |||||||

| CFC‐13 | CClF3 | 75‐72‐9 | 640.0 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 13,900 | 17,200 |

| CFC‐112 | CCl2FCCl2F | 76‐12‐0 | 63.6 | 0.28 | 4,880 | ||

| CFC‐112a | CCl3CClF2 | 76‐11‐9 | 52.0 | 0.25 | 3,740 | ||

| CFC‐113a | CCl3CF3 | 354‐58‐5 | 55.0 | 0.24 | 4,140 | ||

| CFC‐114a | CCl2FCF3 | 374‐07‐2 | 105.0 | 0.30 | 7,850 | ||

| E‐R316c | trans cyc (‐CClFCF2CF2CClF‐) b | 3832‐15‐3 | 75.0 | 0.27 | 4,470 | ||

| Z‐R316c | cis cyc (‐CClFCF2CF2CClF‐) b | 3934‐26‐7 | 114.0 | 0.30 | 5,990 | ||

| CFC 1112 | CClF=CClF | 598‐88‐9 | 7.1 days | 0.01 | <1 | ||

| CFC 1112a | CCl2 = CF2 | 79‐35‐6 | 2.3 days | 0.01 | <1 | ||

| 1,1,2‐trichloro‐2‐fluoroethene | CCl2 = CClF | 359‐29‐5 | (0.13) | ||||

| Chlorotrifluoroethylene | CF2 = CClF | 79‐38‐9 | (0.11) | ||||

|

Hydrochlorofluorocarbons | |||||||

| HCFC‐21 | CHCl2F | 75‐43‐4 | 1.7 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 148 | 168 |

| HCFC‐31 | CH2ClF | 593‐70‐4 | 1.2 | 0.07 | 83 | ||

| HCFC‐121 | CHCl2CCl2F | 354‐14‐3 | 1.1 | 0.15 | 61 | ||

| HCFC‐122 | CHCl2CClF2 | 354‐21‐2 | 0.9 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 59 | 59 |

| HCFC‐122a | CHClFCCl2F | 354‐15‐4 | 3.1 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 258 | 257 |

| HCFC‐123 | CHCl2CF3 | 306‐83‐2 | 1.3 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 79 | 95 |

| HCFC‐123a | CHClFCClF2 | 354‐23‐4 | 4.0 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 370 | 415 |

| HCFC‐124 | CHClFCF3 | 2837‐89‐0 | 5.9 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 527 | 627 |

| HCFC‐124a | CHF2CClF2 | 354‐25‐6 | 17.0 | 0.25 | 2,170 | ||

| HCFC‐132 | CHClFCHClF | 431‐06‐1 | 1.7 | 0.14 | 128 | ||

| HCFC‐132a | CHCl2CHF2 | 471–43‐2 | 1.1 | 0.13 | 74 | ||

| HCFC‐132c | CH2FCCl2F | 1842‐05‐3 | 4.1 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 338 | 359 |

| HCFC‐133a | CH2ClCF3 | 75–88‐7 | 4.6 | 0.15 | 407 | ||

| HCFC‐141 | CH2ClCHClF | 430‐57‐9 | 1.1 | 0.07 | 49 | ||

| HCFC‐225ca | CHCl2CF2CF3 | 422‐56‐0 | 1.9 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 127 | 143 |

| HCFC‐225cb | CHClFCF2CClF2 | 507‐55‐1 | 5.9 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 525 | 596 |

| HCFO‐1233zd(E) | (E)‐CF3CH=CHCl | 102687‐65‐0 | 42.5 days | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1 | 4 |

| HCFO‐1233zd(Z) | (Z)‐CF3CH=CHCl | 99728‐16‐2 | 13.0 days | 0.02 | <1 | ||

| (E/Z)‐1‐chloro‐2‐fluoro‐ethene | (E/Z)‐CHCl = CHF | 460‐16‐2 | 1.8 days | 0.001 | <1 | ||

|

Hydrofluorocarbons | |||||||

| HFC‐41 | CH3F | 593‐53‐3 | 2.8 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 116 | 142 |

| HFC‐134 | CHF2CHF2 | 359‐35‐3 | 10.0 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1,120 | 1,330 |

| HFC‐143 | CH2FCHF2 | 430‐66‐0 | 3.6 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 328 | 382 |

| HFC‐152 | CH2FCH2F | 624‐72‐6 | 0.5 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 16 | 23 |

| HFC‐161 | CH3CH2F | 353‐36‐6 | 80.0 days | 0.02 | 0.02 | 4 | 5 |

| HFC‐227ca | CF3CF2CHF2 | 2252‐84‐8 | 30.0 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 2,640 | 3,140 |

| HFC‐236cb | CH2FCF2CF3 | 677‐56‐5 | 13.4 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 1,210 | 1,420 |

| HFC‐236ea | CHF2CHFCF3 | 431‐63‐0 | 11.4 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 1,340 | 1,570 |

| HFC‐245ca | CH2FCF2CHF2 | 679‐86‐7 | 6.6 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 716 | 827 |

| HFC‐245cb | CF3CF2CH3 | 1814‐88‐6 | 39.9 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 4,620 | 4,790 |

| HFC‐245ea | CHF2CHFCHF2 | 24270‐66‐4 | 3.2 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 235 | 267 |

| HFC‐245eb | CH2FCHFCF3 | 431‐31‐2 | 3.2 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 290 | 341 |

| HFC‐263fb | CH3CH2CF3 | 421‐07‐8 | 1.1 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 76 | 78 |

| HFC‐272ca | CH3CF2CH3 | 420‐45–1 | 9.0 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 144 | 629 |

| HFC‐329p | CHF2CF2CF2CF3 | 375‐17‐7 | 32.0 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 2,360 | 3,040 |

| HFO‐1123 | CHF=CF2 | 359‐11‐5 | 1.4 days | 0.002 | <1 | ||

| HFO‐1132a | CH2 = CF2 | 75‐38‐7 | 4.6 days | 0.004 | 0.004 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1141 | CH2 = CHF | 75‐02‐5 | 2.5 days | 0.002 | 0.002 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1225ye(Z) | (Z)‐CF3CF=CHF | 5528‐43‐8 | 10.0 days | 0.02 | 0.02 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1225ye(E) | (E)‐CF3CF=CHF | 5595‐10‐8 | 5.7 days | 0.01 | 0.02 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1234ze(Z) | (Z)‐CF3CH=CHF | 29118‐25‐0 | 10.0 days | 0.02 | 0.02 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1234ze(E) | (E)‐CF3CH=CHF | 29188‐24‐9 | 19.0 days | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1 | 1 |

| HFO‐1234yf | CF3CF=CH2 | 754‐12‐1 | 12.0 days | 0.02 | 0.03 | <1 | <1 |

| HFO‐1336mzz(E) | (E)‐CF3CH=CHCF3 | N/A | 0.3 | 0.13 | 19 | ||

| HFO‐1336mzz(Z) | (Z)‐CF3CH=CHCF3 | 692‐49‐9 | 27.0 days | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2 | 2 |

| HFO‐1243zf | CF3CH=CH2 | 677‐21‐4 | 9.0 days | 0.01 | 0.02 | <1 | <1 |

| HFC‐1345zfc | CF3CF2CH=CH2 | 374‐27‐6 | 9.0 days | 0.01 | 0.02 | <1 | <1 |

| 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,6‐Nonafluorohex‐1‐ene | n‐C4F9CH=CH2 | 19430‐93‐4 | 9.0 days | 0.03 | 0.03 | <1 | <1 |

| 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8‐Tridecafluorooct‐1‐ene | n‐C6F13CH=CH2 | 25291‐17‐2 | 9.0 days | 0.03 | 0.03 | <1 | <1 |

| 3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,9,9,10,10,10‐Heptadecafluorodec‐1‐ene | n‐C8F17CH=CH2 | 21652‐58‐4 | 9.0 days | 0.03 | 0.04 | <1 | <1 |

| 1‐Propene, 3,3,3‐trifluoro‐2‐(trifluoromethyl)‐ | (CF3)2C=CH2 | 382‐10‐5 | 10.3 days | 0.03 | <1 | ||

| 1,1,2,2,3,3‐hexafluorocyclopentane | cyc (‐CF2CF2CF2CH2CH2‐) | 123768‐18‐3 | 1.6 | 0.20 | 126 | ||

| 1,1,2,2,3,3,4‐heptafluorocyclopentane | cyc (‐CF2CF2CF2CHFCH2‐) | 15290‐77‐4 | 2.8 | 0.24 | 243 | ||

| 1,3,3,4,4,5,5‐heptafluorocyclopentene | cyc (‐CF2CF2CF2CF=CH‐) | 1892‐03‐1 | 0.6 | 0.21 | 47 | ||

| (4R,5R)‐1,1,2,2,3,3,4,5‐octafluorocyclopentane | trans‐cyc (‐CF2CF2CF2CHFCHF‐) b | 158,389‐18‐5 | 3.2 | 0.26 | 271 | ||

| HFO‐1438ezy(E) | (E)‐(CF3)2CFCH=CHF | 14149‐41‐8 | 0.3 | 0.08 | 9 | ||

| HFO‐1447fz | CF3(CF2)2CH=CH2 | 355‐08‐8 | 9.0 days | 0.03 | <1 | ||

| 1,3,3,4,4‐pentafluorocyclobutene | cyc (‐CH=CFCF2CF2‐) | 374‐31‐2 | 0.7 | 0.27 | 97 | ||

| 3,3,4,4‐tetrafluorocyclobutene | cyc (‐CH=CHCF2CF2‐) | 2714‐38‐7 | 84.0 days | 0.21 | 27 | ||

| 3‐Fluoro‐1‐propene | CH2 = CHCH2F | 818‐92‐8 | (0.06) | ||||

| 1‐Fluorohexane | n‐C6H13F | 373‐14‐8 | (0.04) | ||||

| Fluorobenzene | C6H5‐F | 462‐06‐6 | (0.07) | ||||

|

Chlorocarbons and hydrochlorocarbons | |||||||

| Chloroethane | CH3CH2Cl | 75‐00‐3 | 48.0 days | 0.004 | <1 | ||

| 1,1‐Dichloroethane | CH3CHCl2 | 75‐34‐3 | (0.03) | ||||

| 1,2‐Dichloroethane | CH2ClCH2Cl | 107‐06‐2 | 82.0 days | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 |

| 1,1,2‐Trichloroethane | CH2ClCHCl2 | 79‐00‐5 | (0.05) | ||||

| 1,1,1,2‐Tetrachloroethane | CH2ClCCl3 | 630‐20‐6 | (0.10) | ||||

| 1,1,2,2‐Tetrachloroethane | CHCl2CHCl2 | 79‐34‐5 | (0.10) | ||||

| 1,1,2‐Trichloroethene | CHCl = CCl2 | 79‐01‐6 | 5.6 days | 0.01 | <1 | ||

| 1,1,2,2‐Tetrachloroethene | CCl2 = CCl2 | 127‐18‐4 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 7 | ||

| 2‐Chloropropane | CH3CHClCH3 | 75‐29‐6 | 22.0 days | 0.004 | <1 | ||

| Chloromethyl benzene | C6H5‐CH2Cl | 100‐44‐7 | (0.02) | ||||

| 3‐Chloro‐1‐propene | CH2 = CHCH2Cl | 107‐5‐1 | (0.05) | ||||

| 1‐Chloro‐4‐methylbenzene | p‐Cl‐C6H4‐CH3 | 106‐43‐4 | (0.05) | ||||

| 3,4‐Dichloro‐1‐butene | CH2ClCHClCH=CH2 | 760‐23‐6 | (0.06) | ||||

| 1‐Chloro‐3‐methylbenzene | m‐Cl‐C6H4‐CH3 | 108‐41‐8 | (0.05) | ||||

| 2,3‐Dichloropropene | CH2ClCCl = CH2 | 78‐88‐6 | (0.05) | ||||

| 1‐Chloro‐2‐methylbenzene | o‐Cl‐C6H4‐CH3 | 95‐49‐8 | (0.04) | ||||

| 1,2‐Dichloropropene | CHCl = CClCH3 | 563‐54‐2 | (0.03) | ||||

| 1‐Chloropentane | CH3(CH2)3CH2Cl | 543‐59‐9 | (0.02) | ||||

| 1‐Chlorobutane | CH3(CH2)2CH2Cl | 109‐69‐3 | 4.5 days | 0.001 | <1 | ||

| 1‐Chloro‐2‐methylpropane | (CH3)2CHCH2Cl | 513‐36‐0 | (0.02) | ||||

| Chloroethene | CH2 = CHCl | 75‐01‐4 | (0.04) | ||||

| 1,2‐Dichloroethene (E) | (E)‐CHCl = CHCl | 156‐60‐5 | (0.09) | ||||

| Hexachloro‐1,3‐butadiene | CCl2 = CClCCl = CCl2 | 87‐68‐3 | (0.14) | ||||

| 1,3‐Dichloropropene (E) | (E)‐CHCl = CHCH2Cl | 10061‐02‐6 | (0.06) | ||||

| 1,3‐Dichloropropene (Z) | (Z)‐CHCl = CHCH2Cl | 10061‐01‐5 | (0.06) | ||||

| 1,3‐Dichloropropane | CH2ClCH2CH2Cl | 142‐28‐9 | (0.03) | ||||

| Chlorobenzene | C6H5‐Cl | 108‐90‐7 | (0.04) | ||||

| 1,4‐Dichlorobenzene | p‐Cl‐C6H4‐Cl | 106‐46‐7 | (0.08) | ||||

| 1,3‐Dichlorobenzene | m‐Cl‐C6H4‐Cl | 541‐73‐1 | (0.08) | ||||

| 1,2‐Dichlorobenzene | o‐Cl‐C6H4‐Cl | 95‐50‐1 | (0.05) | ||||

| 1,2‐Dichloroethylene (Z) | (Z)‐CHCl = CHCl | 156‐59‐2 | (0.04) | ||||

| Hexachloro‐1,3‐cyclopentadiene | C5Cl6 | 77‐47‐4 | (0.11) | ||||

| 3‐Chloro‐1‐propyne | CH2ClC ≡ CH | 624‐65‐7 | (0.02) | ||||

|

Bromocarbons, hydrobromocarbons, and halons | |||||||

| Dibromomethane | CH2Br2 | 74‐95‐3 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1 | 2 |

| Halon‐1201 | CHBrF2 | 1511‐62‐2 | 4.9 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 376 | 398 |

| Halon‐1202 | CBr2F2 | 75‐61‐6 | 2.5 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 231 | 226 |

| Halon‐2301 | CH2BrCF3 | 421‐06‐7 | 3.2 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 173 | 186 |

| Halon‐2311 (Halothane) | CHBrClCF3 | 151‐67‐7 | 1.0 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 41 | 47 |

| Halon‐2401 | CHBrFCF3 | 124‐72‐1 | 2.9 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 184 | 211 |

| Tribromomethane | CHBr3 | 75‐25‐2 | 57.0 days | 0.01 | <1 | ||

| Halon‐1011 | CH2BrCl | 74‐97‐5 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 5 | ||

| Bromoethane | CH3CH2Br | 74‐96‐4 | 50.0 days | 0.01 | <1 | ||

| 1,2‐Dibromoethane | CH2BrCH2Br | 106‐93‐4 | 89.0 days | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| 1‐Bromopropane | CH3CH2CH2Br | 106‐94‐5 | 15.0 days | 0.002 | <1 | ||

| 2‐Bromopropane | CH3CHBrCH3 | 75‐26‐3 | 20.0 days | 0.004 | <1 | ||

| Bromomethyl benzene | C6H5‐CH2Br | 100‐39‐0 | (0.03) | ||||

| 3‐Bromo‐1‐propene | CH2 = CHCH2Br | 106‐95–6 | (0.04) | ||||

| Bromine Nitrate | BrONO2 | 40423‐14‐1 | (0.10) | ||||

| Bromoethene | CH2 = CHBr | 593‐60‐2 | (0.04) | ||||

|

Fully fluorinated species | |||||||