Abstract

Previous studies have found impaired affective decision-making, as measured by the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), in various antisocial populations. This is the first study to compare the IGT in violent and nonviolent incarcerated American youth. The IGT was administered to 185 incarcerated adolescent male offenders charged with either nonviolent (38.4%) or violent (61.6%) crimes. General linear mixed models and t tests were used to assess differences between the groups. The full sample performed worse than if they had selected from the decks at random. The violent offenders performed more poorly than the nonviolent offenders overall, primarily because they preferred “disadvantageous” Deck B to a greater degree; however, they did demonstrate some degree of learning by the final block of the task. Adolescent offenders demonstrate impaired affective decision-making. Behavior suggested preferential attention to frequency of loss and amount of gain and inattention to amount of loss.

Keywords: adolescence, antisocial behavior, decision-making, juvenile offenders, violence, incarceration

The prevalence of criminal behavior is significantly higher in older adolescents as compared with children and adults. In 2010, arrest rates for both violent and property crimes in the United States were highest among youth aged 17 to 18 years (Sickmund & Puzzanchera, 2014). This “age-crime curve” is consistent across Western countries and time periods (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983) and widely acknowledged to reflect a common increase in offending in adolescence with a corresponding decrease in adulthood (Cauffman, Fine, Mahler, & Simmons, 2018; Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983).

A growing body of interdisciplinary literature has suggested that neurodevelopmen-tal timelines may contribute to this peak in antisocial and risky behavior. Many researchers have argued that the functional developmental timing of neural systems, specifically those implicated in emotional processing and cognitive regulation, leads to heightened vulnerability for impaired affective decision-making in adolescence (Casey, Heller, Gee, & Cohen, 2017; Casey, Jones, & Hare, 2008; Somerville, Jones, & Casey, 2010; Steinberg, 2007, 2008). Compared with adults, adolescents are less able to anticipate consequences of their actions, less willing to delay gratification (Steinberg et al., 2009), more sensitive to rewards, and less sensitive to aversive stimuli (Cauffman et al., 2010; Crone, Vendel, & van der Molen, 2003). This behavioral research is supported by brain imaging findings surrounding areas related to rewards, inhibition, and emotion (Galvan et al., 2006; Galvan, Hare, Voss, Glover, & Casey, 2007; Silverman, Jedd, & Luciana, 2015).

While risky decision-making is relatively normative in youth, this study examines a subset of adolescents who have demonstrated particularly poor decision-making resulting in involvement with the criminal justice system. Both the developmental psychology and criminological literature suggest that impaired affective decision-making is a notable characteristic of youth offenders as they may be particularly swayed by monetary incentives (e.g., selling drugs) and/or more likely to react without thinking in the context of emotionally charged situations (e.g., violent assault). This study will test whether adolescent offenders who have demonstrated poor decision-making in real-world contexts also show deficits in decision-making as indexed by a neurocognitive task, the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, & Anderson, 1994). We will then examine differences in performance between violent and nonviolent offenders, as categorized by the crimes with which they have been charged.

Although the IGT (see below) has been well studied in youth community samples of convenience (Almy, Kuskowski, Malone, Myers, & Luciana, 2017; Cauffman et al., 2010; Hooper, Luciana, Conklin, & Yarger, 2004), there is limited empirical research involving clinically antisocial youth (see Ernst et al., 2003; Miura, 2009, for exceptions), and none to our knowledge examining American youth involved in the criminal justice system. Research elucidating the cognitive mechanisms of decision-making in adolescent offenders offers the potential to help identify those at risk of offending (Popma & Raine, 2006). It may also promote more developmentally appropriate sentencing strategies for youth when balancing justice, punishment, and rehabilitation. For example, in the context of classical deterrence theory (Beccaria, 1988), a better understanding of youths’ affective decision-making may shed light on the relative efficacy of emphasizing swiftness, certainty, or severity of punishment and its impact on both subsequent offending and youths’ future psychosocial developmental trajectory.

IGT

The IGT (Bechara et al., 1994) is a complex neurocognitive task that was originally designed to mimic real-life decision-making under conditions of ambiguity and risk. It was initially used to examine cognitive deficits among otherwise healthy adults with ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) lesions. The vmPFC damage is characterized by marked disturbances in decision-making, insensitivity to future consequences, and poor social conduct. These deficits are sometimes referred to as “acquired sociopathy.” Neuroimaging studies of healthy adolescents and adults suggest that engagement in the IGT recruits both the frontal cortex and the amygdala (Buelow & Suhr, 2009), two areas highly implicated in antisocial behavior and emotion processing (Umbach, Berryessa, & Raine, 2015; Yang & Raine, 2009).

The IGT is a card game in which participants are instructed to win as much pretend “money” as possible. In the original and computerized versions of the task, individuals are instructed to select one card at a time from four different decks for a total of 100 selections (trials). Two (A′ and B′) are “disadvantageous” decks, which have high immediate and consistent rewards coupled with even higher unpredictable losses resulting in long-term loss, whereas two other decks (C′ and D′) are “advantageous” decks associated with lower immediate rewards, but even lower occasional losses resulting in long-term net gain. In the early stages of engagement in the task, when conditions are ambiguous and unknown, individuals are expected to make random choices, selecting cards from a mixture of the advantageous and disadvantageous decks. By the latter half of the task, once conditions become more familiar, healthy individuals typically learn strategies for increasing long-term gain such that they shift their choice-making to prioritize the advantageous decks (Hooper et al., 2004). When the 100 trials are divided into five blocks of 20 trials, the learning-based improvements in performance are typically seen within the final two blocks. A common summary measure of the task is Net Total, which is the number of total disadvantageous card selections subtracted from the number of total advantageous card selections. In addition, Net Total scores are calculated for each of the five blocks to examine the effects of experience and learning on task performance. Finally, disaggregation of the “advantageous” and “disadvantageous” decks may reveal specific deck preferences in line with greater attention to frequency or amount of punishment/reward.

The IGT has been used in numerous studies of children, adolescents, and adults in community (Almy et al., 2017; Denburg et al., 2007; Hooper et al., 2004; Huizenga, Crone, & Jansen, 2007; Overman et al., 2004), clinical (Kessler & Levitt, 1999; Kully-Martens, Treit, Pei, & Rasmussen, 2013; Shurman, Horan, & Nuechterlein, 2005), and forensic (Schmitt, Brinkley, & Newman, 1999; Yechiam et al., 2008) samples as a laboratory measure of decision-making (see Buelow & Suhr, 2009). In healthy adolescents, poor performance on the Iowa Gambling Test has been associated with risky behaviors such as binge drinking (Xiao et al., 2009) and adolescent smoking (Xiao, Koritzky, Johnson, & Bechara, 2013). Various clinical populations have demonstrated impaired performance on the IGT, including individuals with substance use disorder (e.g., Barry & Petry, 2008), pathological eating behaviors (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity; Brogan, Hevey, & Pignatti, 2010), and severe mental health disorders (Adida et al., 2008; Ritter, Meador-Woodruff, & Dalack, 2004; Schuermann, Kathmann, Stiglmayr, Renneberg, & Endrass, 2011), although among individuals with psychopathic traits, findings have been mixed or null (Beszterczey, Nestor, Shirai, & Harding, 2013; Hughes, Dolan, Trueblood, & Stout, 2015; Losel & Schmucker, 2004).

Empirical studies have examined developmental changes in performance on the IGT or child-friendly variants across childhood and adolescence. Although many studies have demonstrated that the frequency of advantageous card selection increases linearly from school age to late adolescence (Almy et al., 2017; Crone & van der Molen, 2004; Crone et al., 2003), other studies have evidenced quadratic effects where adolescents perform poorly relative to children and adults (D. G. Smith, Xiao, & Bechara, 2012). These divergent findings may be the result of how the studies operationalize age (e.g., as a linear vs. categorical variable) and/or study methodology (longitudinal vs. cross sectional). The majority of studies are cross sectional (see Almy et al., 2017, for an exception) but treat age differently. Crone et al. (2003) and Crone and van der Molen (2004) grouped their children by age, whereas D. G. Smith et al. (2012) treated age as a linear variable. These methodological differences suggest that categorizing age may mask the slight dip in performance exhibited in certain years of adolescence as demonstrated by the D. G. Smith and colleagues’ (2012) study.

IGT IN FORENSIC POPULATIONS

Compared with studies with adults, there is little empirical research using the IGT in forensic juvenile samples. One exception is a study by Miura (2009) of 317 detained Japanese males aged 19 and younger (lower bound age was not reported). He found that both self-reported violent and nonviolent offenders were more likely to choose cards from disadvantageous decks relative to the number of cards from the advantageous decks; no significant differences were found between the two groups (violent MNet Total = 52.5, SD= 8.4; nonviolent MNet Total = 54.4, SD = 9.4). More specific details regarding the number of selections from each deck or progress over time were not reported.

Adolescents diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorders (i.e., conduct disorder [CD] and oppositional defiant disorder [ODD]) are overly represented in the juvenile justice system (Teplin, Abram, McClelland, Dulcan, & Mericle, 2002; Teplin et al., 2006; Wasserman, McReynolds, Lucas, Fisher, & Santos, 2002); one estimate suggests more than 40% of detained youth meet diagnostic criteria for a disruptive behavior disorder (Teplin et al., 2006). Hobson, Scott, and Rubia (2011) found that community-based clinically referred (but not involved in the justice system) adolescents aged 10 to 17 who met criteria for CD/ODD made more disadvantageous choices on the IGT compared with same age controls without a history of behavior problems.

Studies on IGT performance among incarcerated or justice-involved adult samples have demonstrated mixed findings. Although some report that adult offenders across wide age ranges demonstrate poor overall performance on the IGT relative to community controls (Yechiam et al., 2008), others found no differences in overall performance between incarcerated adult offenders and nonincarcerated controls (Hughes et al., 2015). In the Yechiam et al. (2008) study, performance on the IGT was associated with specific types of offenses, for example, participants who used substances and those who had been convicted of sex offenses tended to overweigh gains (disproportionately selecting from high reward decks), whereas inmates convicted of assault/murder tended to focus on their most recent results and ignored more distant outcomes resulting in less consistent choices.

Several studies have examined learning in offenders by examining IGT performance over the course of the task. Schmitt et al. (1999) found that incarcerated adults (40 years old and younger) demonstrated some degree of improvement over the course of the task as indicated by fewer selections from the disadvantageous decks in the later blocks. However, because they initially selected so frequently from the disadvantageous decks, learning was relative; that is, even by the final block, they continued to select more often from the disadvantageous decks than from the advantageous decks. In contrast, a longitudinal study of recently released offenders aged 22 to 51 years found that recidivistic adult offenders demonstrated poor performance over the entire course of the task compared with nonrecidivistic and control individuals (Beszterczey et al., 2013). In the Hughes et al. (2015) study cited above, neither the offenders nor the community controls demonstrated any degree of learning across the task.

The overwhelming majority of studies using the IGT report the aggregated proportion of disadvantageous and advantageous decks. A general review of the IGT literature found that only 17 of the 479 included studies reported the proportion of choices from each of the decks (Steingroever, Wetzels, Horstmann, Neumann, & Wagenmakers, 2013). Among offending populations, most studies attribute poor performance to impulsive and perseverative selection of disadvantageous decks associated with high immediate rewards at the expense of long-term outcomes. However, given the variety of punishment and reward contingencies in the IGT, a more granular analysis of performance by an individual deck can increase our understanding of to which particular aspects of the task participants attend and may have specific implications for treatment and/or sentencing options. For example, selecting cards predominantly from the punishment decks, but equally between the two options, suggests a relative insensitivity to frequency of punishment and an overarching attendance to amount of reward (low utility of certainty). Alternatively, selecting cards disproportionately from Deck B relative to Deck A suggests a degree of attention to frequency (certainty) as well as amount of punishment (severity). To our knowledge, there are no studies of the IGT with forensic populations that have examined the number of cards selected from each deck.

Although we do expect to see impaired performance overall in the sample, given the relatively sparse and highly discrepant literature, we have no a priori hypothesis as to how nonviolent and violent offenders compare either in terms of overall performance or in performance over time. On one hand, violent offenders may perform particularly poorly on the task, because violent offenses are relatively high cost, and, thus, may reflect significant maladaptive decision-making (Jensen & Metsger, 1994). On the other hand, violent offenders may demonstrate impaired decision-making in highly affective or ambiguous contexts, but more normative performance once conditions are known. Nonviolent offenses such as selling drugs and theft may be more habitual types of offenses, in which the offenders are aware of potential consequences and choose to engage in the behavior, regardless of those consequences (albeit with adaptations to reduce risk of law enforcement detection; May & Hough, 2001). That may suggest there will be little to no learning or shift in behavior over the course of the task.

AIMS AND QUESTIONS OF THE PRESENT STUDY

Although the IGT is a well-utilized neurocognitive task in research on healthy and clinical populations, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first application of the task to a large incarcerated population of American adolescents. In light of studies that support the predictive utility of the IGT for real-world risk-taking behaviors such as binge drinking and smoking in community-based adolescents (Johnson et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2013) and for recidivism in justice-involved adults (Beszterczey et al., 2013), the task is well suited to this population.

This article aims to descriptively assess performance on the IGT in a group of adolescent male offenders and to investigate potential differences in behavior and performance between violent and nonviolent offenders with the following research questions:

Research Question 1: How do adolescent offenders perform on the IGT and does that performance change over time?

Research Question 2: Are there differences in learning behavior and performance (e.g., Net Total [advantageous minus disadvantageous choices]) between violent and nonviolent offenders?

Research Question 3: What aspects of the task does each subtype of offender prioritize (as measured by deck selection preferences)?

MATERIALS AND METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

As part of a larger study (Leonard et al., 2013), 268 male adolescents between the ages of 16 and 18 were recruited from Rikers Correctional Facility in New York City. At the time the data were collected in 2009 and 2010, 16-and 17-year-old youth were charged and detained in the adult criminal justice system. Youth were invited to participate if they had at least 6 weeks left on their sentence or estimated length of stay, could complete an interview in English, and were between the ages of 16 and 18.

A subset of 185 youths were selected for inclusion in this study, based on completed questionnaire and task data and availability of official charges. Of the 268 participants, five were missing IGT data, six were missing estimated IQ data, and 72 were missing information about criminal charges. The remaining 185 comprised the final sample. Charge information was obtained through the New York City Department of Corrections online service and the National Victim Notification Network. Youth were excluded from analyses if their charge information was sealed or missing. The majority of the offenders (61.6%) had been charged with a violent felony (e.g., assault with a deadly weapon, second-degree murder), 22.7% had been charged with a nonviolent felony (e.g., criminal sale of a controlled substance, criminal possession of stolen property), 11.9% had been charged with a misdemeanor (unauthorized use of a vehicle, theft), and the remaining 3.8% had been charged with violations of some sort (e.g., administrative, parole). Participants were classified as “violent” if they were charged with at least one violent offense, and “non-violent” otherwise. Participants had spent on average 117 days incarcerated. There were no significant differences between nonviolent and violent offenders in age, estimated IQ, race/ethnicity, or days already spent incarcerated. Basic demographic information is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1:

Participant Demographics

| Type of offender | Violent | Nonviolent | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 114 | 71 | 185 |

| Days already spent incarcerated at time of assessmenta | |||

| M (SD) | 121.17 (139.45) | 111.01 (117.53) | 117.26 (131.19) |

| Age | |||

| M (SD) | 17.36 (0.79) | 17.53 (0.61) | 17.43 (0.73) |

| Race (%) | |||

| Black | 49.1 | 56.3 | 51.9 |

| White | 0.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Hispanic | 24.6 | 31.0 | 27.0 |

| Asian | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| Mixed race | 16.6 | 5.7 | 11.9 |

| Otherb | 7.0 | 4.2 | 5.9 |

| Estimated IQ | |||

| M (SD) | 86.88 (15.99) | 90.92 (15.19) | 88.43 (15.58) |

Missing data on time incarcerated for two nonviolent offenders and four violent offenders.

Includes any participant who selected only the “other’ race option.

Youth who were 18 years old or legally emancipated provided informed consent. Youth less than 18 years of age provided informed assent, and parental consent was obtained for participation. All procedures were approved by the New York University Institutional Review Board and the New York City Department of Corrections.

MEASURES

IGT

Four decks of cards, each of which consists of 60 cards, were presented simultaneously on a computer screen to the participants. Participants started the task with a “loan” of US$2,000 in pretend money and were told to select 100 cards total from any of the four decks of cards. They were informed that the task was not random and that the goal was to collect as much “play” money as possible (Bechara, 2007). After each card selection, participants were informed how much money they won or lost as a result of their card selection. Two decks (A′ and B′) yield high immediate monetary returns, but are disadvantageous in the long term. Although both of the disadvantageous decks result in a net loss over repeated draws (potential net loss of up to US$3,750), Deck A′ contained frequent (50% of cards) small punishments, whereas Deck B′ contained less frequent (10%) but much larger punishments. Two decks (C′ and D′) yield relatively low immediate monetary returns, but are advantageous in the long term. Similar to the disadvantageous decks, Deck C′ contains frequent (50%) small punishments, and Deck D′ contains infrequent (10%) larger punishments, although both decks result in the same net gain over repeated draws (potential net gain of up to US$1,875) (see Table 2 for a graphic of the deck details in this study).

TABLE 2:

Iowa Gambling Task Design

| Characteristics | Deck A′ | Deck B′ | Deck C′ | Deck D′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Disadvantageous | Disadvantageous | Advantageous | Advantageous |

| Punishment pattern | Frequent/small amount | Infrequent/large amount | Frequent/small amount | Infrequent/large amount |

| Net | −US$3,750 | −US$3,750 | + US$1,875 | + US$1,875 |

Estimated IQ

The reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test-Third Edition (WRAT-3; Wilkinson, 1993) is an educational achievement battery designed for individuals aged 12 to 75 years and, similar to previous studies (e.g., T. D. Smith, Smith, & Smithson, 1995; Vance & Fuller, 1995), was used as an approximation of verbal IQ. Participants are asked to read aloud letters and words, and the number of correctly read letters and words are summed and converted to standard scores, percentiles, and school grade equivalents. In clinical populations of children referred for academic difficulties, the WRAT-3 subtests have shown moderate to high correlations with Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) subtests, ranging from r = .55 to r= .71 (T. D. Smith et al., 1995; Vance & Fuller, 1995).

Measures of Performance

In all forms of the IGT, participants do not know the magnitude or probability of outcomes when making choices, and, thus, have to rely on learning over time to make decisions (it is assumed that participants will make better decisions later in the task, after the conditions have been learned, as compared with earlier). Successful performance on the task requires the participant to refrain from making decisions based on short-term large immediate gains in favor of decisions based on smaller immediate gains but greater longterm success. Traditionally—and as demonstrated by the most often used measure of “success,” Net Total—the focus of the IGT is on the long-term outcome (expected value). Net Total is derived by subtracting the total number of disadvantageous selections (from Decks A′ and B′) from the total number of advantageous selections (from Decks C′ and D′; Bechara, Damasio, Tranel, & Anderson, 1998; Bolla, Eldreth, Matochik, & Cadet, 2005; Franken & Muris, 2005). Based on random chance alone, participants should select ~50% good cards, resulting in a Net Total score of 0. Impaired performance has been defined in multiple studies with clinical (Bechara & Damasio, 2002) and community participants (Kerr & Zelazo, 2004) as selecting more than 50% bad cards, and that benchmark will also be used here in the descriptive part of the analyses (see Steingroever et al., 2013, for a review) through the use of t tests (Kerr & Zelazo, 2004).

We will examine several additional outcome measures established in earlier literature, including Net Total, the pattern of this difference by 20-block trials over 100 card plays (Bechara & Damasio, 2002; Bechara et al., 2001; Bechara, Tranel, & Damasio, 2000), and the number of selections from each deck (Cauffman et al., 2010).

ANALYSES

The research questions were assessed using t tests and general linear mixed models with intercepts allowed to vary by participant, and fixed effects of group and either deck type or block, depending on the analysis. Linear mixed models are preferable to other strategies (e.g., analyses of variance [ANOVAs]) in these analyses because they are robust to unequal variance and unbalanced sample sizes (Demidenko, 2013). The ImerTest package (v 3.0-1; Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, 2017) and lmer function from the lme4 package (vl. 1-x19; Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) in R were used for the general linear mixed models. Bootstrapping and bias-corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for the t tests between groups, due to their unequal sizes. There were no significant differences in age, estimated IQ, or time spent incarcerated at time of assessment between the violent and nonviolent offenders, and, thus, they were not included as covariates.

RESULTS

POTENTIAL COVARIATES

Potential covariates were tested for significant associations with performance on the task. Overall performance on the task was unrelated to estimated IQ score (r = .3, p = .73). In addition, likely due to the narrow age range of the participants, performance on the task was unrelated to age (r = −.09, p = .29). There was no association between number of days already spent incarcerated at the time of assessment and performance (r = −.12, p = .09).

FULL SAMPLE

The t distribution was used to compare the basic summary measure of advantageous selections minus disadvantageous selections in the full sample with the mean expected score based on random responding (i.e., 0). That is, if selecting completely at random, the expected score on the task is 0. The participants demonstrated significantly lower than chance performance on the task overall (MNet Total = −11.75, SD = 21.79, t = −7.34, p< .001, Cohen’s d = 0.54). Furthermore, they performed worse than chance on each of the five blocks that comprise the task (all ps < .001).

VIOLENT OFFENDERS VERSUS NONVIOLENT OFFENDERS

Net Total

After applying Welch’s correction to account for unequal variances, an independent samples t test revealed that serious violent offenders (n = 114, MNet Total = −14.14, SD = 23.65) performed more poorly on the IGT than their nonviolent counterparts (n = 71, MNet Total = −7.92, SD = 17.91, t = 2.03, p = .04, Cohen’s d = 0.30, Hedges’s d = 0.30) across the task. Using a bootstrapped sample of 1,000, a bias-corrected and accelerated 95% CI for the difference in means did not include 0, indicating significance, 95% CI = [0.17, 12.28]. This difference was then examined by disaggregating the deck preferences by the offender.

Deck Preferences

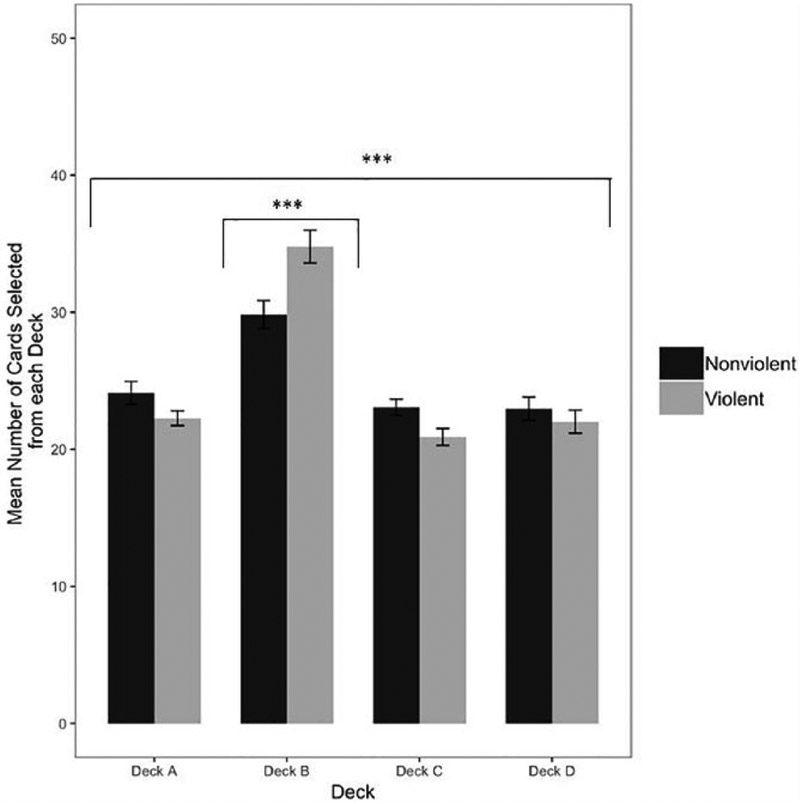

A linear mixed model was conducted to assess interactions between deck preferences and type of offender (violent/nonviolent). As compared with the reference deck (Deck A), both groups selected disproportionately more cards from Deck B (b = 5.70, SE = 1.39, t[732.00] = 4.11, p < .0001). There were no differences between number of selections from Deck A and number of selections from Decks C and D (p = .45, p = .41). The interaction coefficient between group and Deck B was positive and significant (b = 6.82, SE = 1.77, t[732.00] = 3.86, p < .0001), indicating an even greater preference for Deck B in the violent group as compared with the nonviolent group. The interaction coefficients for Decks C and D were nonsignificant (p = .86, p = .61), as was the group variable, which indicates no group differences in Deck A (the reference deck; p = .14). Deck selections by group are shown graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Deck Selection by Group With Standard Error Bars.

***p < .001.

Learning Over Time

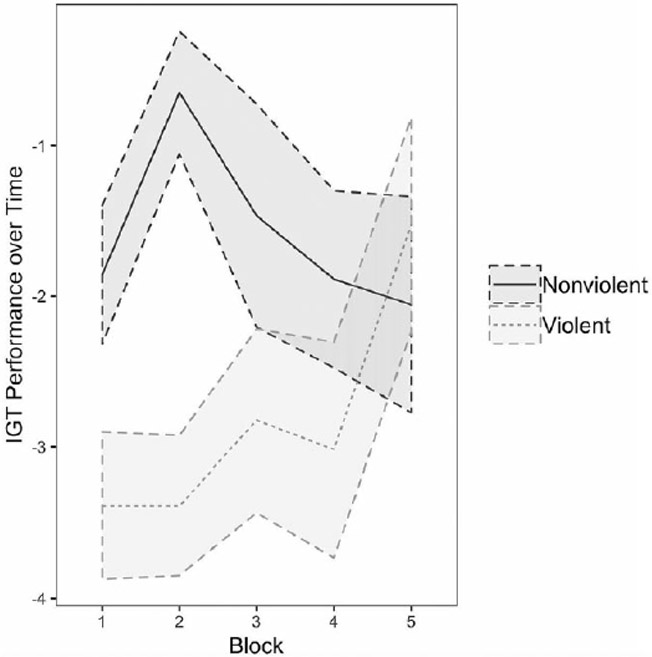

A linear mixed model was conducted to probe main effects and the interaction of group and block, treating block as a continuous variable. There was no main effect of block (b = −0.16, SE = 0.17, t[738] = −0.95, p = .34). The negative main effect of group indicates that the violent group performed worse than the nonviolent group overall (b = −2.96, SE = 0.93, t[589.23] = −3.20, p = .002); however, a Positive Block × Group interaction (b = 0.57, SE = 0.22, t[738] = 2.61, p = .002) suggests that the violent group did show some improvement over time, albeit mild, unlike the nonviolent group. Visual inspection of group averages over time in Figure 2 is consistent with this theory, although we note that this “improved performance” in the violent group still resulted in a mean Net Total in Block 5 of less than 0 (Table 3).

Figure 2: Number of Advantageous Cards Minus Disadvantageous Cards per Block With Shaded Standard Error.

Table 3:

Means and Standard Deviations by Group of Iowa Gambling Task Performance Over Time

| Net Total per Block | Group | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Block 1 | Nonviolent | 71 | −1.86 | 3.89 |

| Violent | 114 | −3.39 | 5.17 | |

| Net Block 2 | Nonviolent | 71 | −0.65 | 3.43 |

| Violent | 114 | −3.39 | 4.92 | |

| Net Block 3 | Nonviolent | 71 | −1.46 | 6.25 |

| Violent | 114 | −2.82 | 6.47 | |

| Net Block 4 | Nonviolent | 71 | −1.89 | 4.96 |

| Violent | 114 | −3.02 | 6.47 | |

| Net Block 5 | Nonviolent | 71 | −2.06 | 6.05 |

| Violent | 114 | −1.53 | 7.59 |

Block was also treated as a factor variable in a follow-up analysis, based on visual inspection of Figure 2, and to probe interaction effects at each block. The reference block was Block 1. The only significant effect was an interaction effect of group and Block 5 (b = 2.06, SE = 0.98, t[732] = 2.10, p = .04), suggesting that the violent group improves over the nonviolent group in Block 5. This further indicates that the improvements shown by the violent group over time are primarily attributed to the final block.

DISCUSSION

This study examined performance on the IGT among a sample of incarcerated male youth. The offenders performed significantly worse than would be expected if they had chosen from the decks at random, both in total and in each block of the task. The offenders were then subdivided into violent and nonviolent groups based on the crime with which they had been charged. As expected, results suggest that both groups demonstrate perseverative and consistent impairment in decision-making. Overall performance was consistent with failure to improve over the course of the task and disproportionate selection from a disadvantageous deck resulting in high rewards but higher punishment with a net loss over the course of the task and within each block.

The differences between the two types of offenders were driven by a greater preference for Deck B within the violent group, above and beyond the preference shown by the nonviolent group. Interestingly, the two types of offenders also demonstrated differential behavior in terms of learning during the task. According to the linear mixed model examining block by group, there was a positive Block 5 × Group interaction for the violent offenders, this, paired with visual inspection of Figure 2 indicates that the violent offenders, unlike the nonviolent offenders, showed some sign of improvement or learning by the final block (choosing fewer disadvantageous cards than in the beginning) when deck contingencies would have been better known. Like the adult offenders in Schmitt et al. (1999), despite the “learning,” even by the final block, they were net negative, continuing to prefer the disadvantageous decks. In contrast, there was no main effect of block when it was treated continuously, nor were there block effects when it was treated as a factor, suggesting a generally flat trajectory of performance over the course of the task and no sign of learning in the nonviolent group.

Few studies have examined this decision-making task in a sample of forensic male adolescents whose real-world choices suggest that their decision-making abilities may be significantly impaired. The summary findings are somewhat consistent with those of Yechiam et al. (2008), who suggested that violent offenders may be particularly poor at future-oriented thinking but differ from Miura (2009) who found impairments overall in antisocial youth, but no differences by offender type (violent/nonviolent). Using the Risky Choice Task, another task designed to measure risky decision-making, several studies have found impaired decision-making in antisocial youth, as compared with controls (Syngelaki, Moore, Savage, Fairchild, & Van Goozen, 2009), and particularly in early-onset antisocial youth, as compared with later onset (Fairchild et al., 2009). These convergent findings lend strength to the idea that antisocial youth are particularly impaired when it comes to decision-making.

As hypothesized by earlier literature (Chiu & Lin, 2007; Huizenga et al., 2007), the summary measure of Net Total disguised significant differential deck selection within the two categories (disadvantageous and advantageous). The negative performance by both groups was primarily driven by a preference for Deck B′, a high reward and infrequent but large punishment deck. This level of performance is consistent with developmental literature that suggests a preference for Deck B′ is common behavior in young children (Huizenga et al., 2007), reflecting a tendency for instant gratification and an inability to consider future consequences of current behavior. The preference for Deck B′ by the offenders, thus, mirrors their real-world behavioral choices and this was particularly true of violent offenders.

Behaviorally and with regard to learning, differences on the IGT were restricted to improvements by Block 5 by the violent offenders. Although this study lacks the granularity of data to examine choices by trial, the pattern suggests that once they discovered the high reward/infrequent punishment scheme of Deck B′, they stuck with that strategy for a period of time, although very gradually began to experiment more by Block 5, showing some degree of learning, albeit delayed relative to similar-aged and even younger community samples (Cauffman et al., 2010). In contrast, the performance of the nonviolent group suggests a lack of learning because by Block 5, they remained at approximately the same level of performance as seen in Block 1.

Because of the age of our sample, some charges were sealed and not available for youth who had been charged with certain severe crimes (e.g., capital crimes). It is, therefore, possible that this methodology excluded youth who may be particularly violent in their offending, but we theorize that including these youth would strengthen rather than diminish the magnitude of our findings. This study depended on official reports of criminal offending. Some studies suggest significant concurrent validity between official and self-reports of criminal offending (Maxfield, Weiler, & Widom, 2000). Others suggest that relying on either alone will underestimate arrests (Kirk, 2006). In all likelihood, more accurate ways of assigning individuals to groups would have led to the recategorization of those who were characterized as nonviolent but had evaded arrest for a violent offense.

Due to institutional rules surrounding the sample population, this study employed “fake” money in contrast to other studies, which have used real (albeit smaller amounts) money (e.g., Almy et al., 2017). Some research suggests that the choice of real versus “fake” money reinforcers does not significantly affect performance on the IGT (Bowman & Turnbull, 2003), whereas others have seen that brain activity patterns during the task were dependent on type of reinforcer (Xu et al., 2018). Even if the “fake” money may have led to more risk taking on the task, there is little reason to believe that would differ by offender subtype.

Considering this is the first study examining the IGT in juvenile offenders in the United States, there are numerous studies that could extend and clarify the findings herein. This study was limited to comparisons between different types of incarcerated male youth offenders. Accordingly, the best comparison we could make to a “control” group was to compare the mean Net Total in the offender group with a mean of 0, which is what would be expected under conditions of chance. Future studies could include demographically matched community controls in an effort to draw more robust conclusions. In addition, because performance in both groups was similar to adult forensic findings, future studies could compare youth and adult samples to concretely test whether decision-making deficits are equally present among both, or particularly significant in youth. Furthermore, our sample disproportionately comprised Hispanic and Black youth from an urban area, and it is unclear whether findings would generalize to youth incarcerated from different backgrounds (i.e., rural), to youth of different racial/ethnic backgrounds, or to female juvenile offenders. Social and structural variables related to offending behavior and involvement in the criminal justice system have disproportionate effects on Black and Hispanic youth (Haynie & Payne, 2006; Proctor & Dalakar, 2003). Furthermore, we did not assess histories of trauma, which has been found to have profound effects on youths’ cognition and behavior (Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). Finally, the youth in this study were incarcerated in a high-stress, adult correctional facility, which was under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice for widespread physically abusive behavior by correctional personnel at the time the data were collected (Leonard et al., 2013; Office of the United States Attorney Southern District of New York, 2014). Both acute and chronic stresses have been shown to promote increases in risk-taking and rewardseeking among adolescent males, notably through decreased activation of the prefrontal cortex (Galvan & Rahdar, 2013; Uy & Galvan, 2017). Future studies should examine justice-involved youth who are detained in facilities designed for juvenile justice populations and include a measure of subjective stress. Finally, a longitudinal study could shed light on whether the findings of Beszterczey et al. (2013) also apply to juveniles, and whether this task may be useful in risk assessments.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This study has both theoretical and practical implications. Our main findings—that adolescent offenders were significantly impaired in a laboratory task indexing risky decisionmaking, and that violent and nonviolent offenders did demonstrate significant (albeit small) differences in behavior and performance on the task—are consistent with the idea that different types of youth offenders may be more or less affected by shifts in the aforementioned three tenets of deterrence. Both types of offenders demonstrated behavior over the course of the task, which suggested dominant attendance initially toward the amount of the reward, and second toward frequency of punishment. Heightened susceptibility to reward is a normative feature of adolescence and a large body of behavioral and neural studies have related this hypersensitivity to increases in risk-taking behavior. However, more recent neuroimaging studies of typically developing adolescents have suggested that reduced sensitivity to negative feedback (Ernst et al., 2005; McCormick & Telzer, 2017) is also associated with increases in risky behavior. Thus, in adolescence, rewards in response to behavioral choices may increase subsequent approach motivation, whereas dampened sensitivity to negative outcomes may reduce motivation to avoid potential negative consequences.

This study intentionally disaggregated the disadvantageous and advantageous decks to examine offender behavior in more detail. In the present report, severe punishments, associated with Deck B′, did not seem to dissuade the youth offenders from preferring this deck. Because the youth did appear sensitive to frequency of punishment, extrapolating from the behavior shown on this task suggests that with regard to adolescents, criminal justice strategies that prioritize certainty and speed over severity in designing sanctions may be more effective than current sentencing policies, which typically emphasize severity. This may be particularly true for violent youth offenders who make significantly worse decisions under conditions of ambiguity and appear to improve after circumstances become more familiar. Reducing ambiguity regarding the consequences of criminal behavior may incrementally improve decision-making in violent youth offenders specifically. This suggestion is hardly new; for example, the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study, carried out in Hawaii by researchers with buy-in from policy-and lawmakers, implemented sentences for low-level offenders, which emphasized certainty and swiftness over severity (Hawken & Kleiman, 2009).

Indeed, a refocus and acknowledgment of important differences between juvenile and adult offenders is in line with current attitudes toward the juvenile criminal justice system expressed by policymakers (H.R. 1809, 2017), juvenile justice researchers (Cauffman et al., 2018), and notably, recent Supreme Court decisions (Graham v. Florida, 2010; Miller v. Alabama, 2012; Roper v. Simmons, 2005) that relied on neurodevelopmental evidence of immature decision-making among adolescents to determine adolescents’ diminished culpability. Despite these recent trends, it is difficult to predict large-scale changes in the juvenile criminal justice system in the near future. Findings suggested by studies like these may also be helpful in promoting incremental changes in risk assessment tools and intervention designs. Recently, interventions informed by neurocognitive science that focus on enhancing decision-making and future-oriented thinking have shown promise among youth at high risk of offending and problematic substance use (Knight, Dansereau, Becan, Rowan, & Flynn, 2015). Finally, forensic assessments of youth offenders might be enhanced if future studies find a relationship between performance on the IGT and treatment outcomes or recidivism (as in Beszterczey et al., 2013). For example, detained youth who perform particularly poorly may be more carefully monitored or provided with extra resources.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the young men who participated in the study, Bethany Casarjian, PhD; Robin Casarjian; and the following project staff: Angela Banfield; Leslie Booker; Christina Laitner, PhD; Jessica Linick, PhD; Rita Mirabelli; Michael Pass; Isaiah Pickens; Audrey Watson, PhD; and Michelle Silverman for data preparation. We would also like to extend our appreciation to the New York City Department of Corrections staff, particularly Deputy Wardens Winette Saunders-Halyard and Erik Berliner, and Officers John Hatzaglou and Maywattie Mahedeo. Marya V Gwadz, PhD; Charles M. Cleland, PhD; and Nim Tottenham, PhD, provided significant scientific input to the methods of the study. Evan Slovak provided assistance in the editing of this manuscript. Funding: T32DA007233-35, R01 DA 024764, to Noelle R. Leonard, PhD, principal investigator.

Biography

Rebecca Umbach, PhD, is a T32 postdoctoral fellow in the Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research program at New York University and a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychology at Columbia University. She received her PhD in Criminology from the University of Pennsylvania. Her work focuses primarily on the putative pathways between environmental risk factors, cognitive development, and externalizing behavior.

Noelle R. Leonard, PhD, is a senior research scientist at the New York University Silver School of Social Work with an expertise in designing, implementing, evaluating, and disseminating behavioral interventions for highly vulnerable youth and adults. These interventions involve a variety of modalities including mindfulness meditation and mobile health technology for homeless/runaway youth, youth involved in the criminal justice adolescent mothers with young children, and youth and adults at high risk of/infected with HIV/AIDS.

Monica Luciana is a distinguished McKnight University professor at the University of Minnesota in the Department of Psychology and a founding member of the UMN Center for Neurobehavioral Development where she conducts longitudinal studies of brain and behavioral development in adolescents using personality measures, cognitive tests, and brain imaging techniques. Funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, she co-directs the Twin Hub of the NIH-funded ABCD Consortium as well as the consortium’s workgroup on neurocognition.

Shichun Ling is a PhD candidate in Criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, with a bachelor’s in Psychology and Social Behavior from the University of California-Irvine and a Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience certificate from the University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on understanding the biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to the etiology of criminal behavior as well as their clinical and legal implications.

Christina Laitner, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and the Clinical Director of the Child and Adolescent Partial Hospitalization Program at NYC Health + Hospitals Bellevue. Her clinical and research interests focus on therapies for treating children and adolescents with traumatic stress.

Contributor Information

REBECCA UMBACH, New York University; Columbia University.

NOELLE R. LEONARD, New York University

MONICA LUCIANA, University of Minnesota.

SHICHUN LING, University of Pennsylvania.

CHRISTINA LAITNER, New York University School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- Adida M, Clark L, Pomietto P, Kaladjian A, Besnier N, Azorin J-M, & Goodwin GM (2008). Lack of insight may predict impaired decision making in manic patients. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 829–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almy B, Kuskowski M, Malone SM, Myers E, & Luciana M (2017). A longitudinal analysis of adolescent decisionmaking with the Iowa Gambling Task. Developmental Psychology, 54, 689–702. doi: 10.1037/dev0000460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry D, & Petry NM (2008). Predictors of decision-making on the Iowa Gambling Task: Independent effects of lifetime history of substance use disorders and performance on the Trail Making Test. Brain and Cognition, 66, 243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beccaria C (1988). On crimes and punishments. New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A (2007). Iowa Gambling Task professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR, Damasio H, & Anderson SW (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50(1–3), 7–15. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, & Damasio H (2002). Decision-making and addiction (part I): Impaired activation of somatic states in substance dependent individuals when pondering decisions with negative future consequences. Neuropsychologia, 40, 16751689. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00015-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, & Anderson SW (1998). Dissociation of working memory from decision making within the human prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 18, 428–437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00428.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Dolan S, Denburg N, Hindes A, Anderson SW, & Nathan PE (2001). Decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in alcohol and stimulant abusers. Neuropsychologia, 39, 376–389. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(00)00136-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Tranel D, & Damasio H (2000). Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions. Brain, 123, 2189–2202. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.11.2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beszterczey S, Nestor PG, Shirai A, & Harding S (2013). Neuropsychology of decision making and psychopathy in high-risk ex-offenders. Neuropsychology, 27, 491–497. doi: 10.1037/a0033162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla KI, Eldreth D, Matochik J, & Cadet J (2005). Neural substrates of faulty decision-making in abstinent marijuana users. NeuroImage, 26, 480–492. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman CH, & Turnbull OH (2003). Real versus facsimile reinforcers on the Iowa Gambling Task. Brain and Cognition, 53, 207–210. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan A, Hevey D, & Pignatti R (2010). Anorexia, bulimia, and obesity: Shared decision making deficits on the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT). Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16, 711–715. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelow MT, & Suhr JA (2009). Construct validity of the Iowa Gambling Task. Neuropsychology Review, 19, 102–114. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9083-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Heller AS, Gee DG, & Cohen AO (2017). Development of the emotional brain. Neuroscience Letters, 693, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.11.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM, & Hare TA (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124, 111–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Fine A, Mahler A, & Simmons C (2018). How developmental science influences juvenile justice reform. UC Irvine Law Review, 8(1), 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cauffman E, Shulman EP, Steinberg L, Claus E, Banich MT, Graham S, & Woolard J (2010). Age differences in affective decision making as indexed by performance on the Iowa Gambling Task. Developmental Psychology, 46, 193–207. doi: 10.1037/a0016128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Y-C, & Lin C-H (2007). Is deck C an advantageous deck in the Iowa Gambling Task? Behavioral and Brain Functions, 3(1), Article 37. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, & van der Molen MW (2004). Developmental changes in real life decision making: Performance on a gambling task previously shown to depend on the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Developmental Neuropsychology, 25, 251–279. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2503_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Vendel I, & van der Molen MW (2003). Decision-making in disinhibited adolescents and adults: Insensitivity to future consequences or driven by immediate reward? Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 1625–1641. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00386-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E (2013). Mixed models: Theory and applications with R (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Denburg NL, Cole CA, Hernandez M, Yamada TH, Tranel D, Bechara A, & Wallace RB (2007). The orbitofrontal cortex, real-world decision making, and normal aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1121, 480–498. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Grant SJ, London ED, Contoreggi CS, Kimes AS, & Spurgeon L (2003). Decision making in adolescents with behavior disorders and adults with substance abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 33–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Nelson EE, Jazbec S, McClure EB, Monk CS, Leibenluft E, & Pine DS (2005). Amygdala and nucleus accumbens in responses to receipt and omission of gains in adults and adolescents. NeuroImage, 25, 1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild G, van Goozen SHM, Stollery SJ, Aitken MRF, Savage J, Moore SC, & Goodyer IM (2009). Decision making and executive function in male adolescents with early-onset or adolescence-onset conduct disorder and control subjects. Biological Psychiatry, 66, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2009.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken IHA, & Muris P (2005). Individual differences in decision-making. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Hare TA, Parra CE, Penn J, Voss H, Glover G, & Casey BJ (2006). Earlier development of the accumbens relative to orbitofrontal cortex might underlie risk-taking behavior in adolescents. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 26, 6885–6892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1062-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Hare T, Voss H, Glover G, & Casey BJ (2007). Risk-taking and the adolescent brain: Who is at risk? Developmental Science, 10(2), F8–F14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, & Rahdar A (2013). The neurobiological effects of stress on adolescent decision making. Neuroscience, 249, 223–231. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUR0SCIENCE.2012.09.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010).

- Hawken A, & Kleiman M (2009). Managing drug involved probationers with swift and certain sanctions: Evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/229023.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, & Payne DC (2006). Race, friendship networks, and violent delinquency. Criminology, 44, 775–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00063.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, & Gottfredson M (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American Journal of Sociology, 89, 552–584. doi: 10.2307/2779005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson CW, Scott S, & Rubia K (2011). Investigation of cool and hot executive function in ODD/CD independently of ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 1035–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02454.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper CJ, Luciana M, Conklin HM, & Yarger RS (2004). Adolescents’ performance on the Iowa Gambling Task: Implications for the development of decision making and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Developmental Psychology, 40, 1148–1158. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes MA, Dolan MC, Trueblood JS, & Stout JC (2015). Psychopathic personality traits and Iowa Gambling Task performance in incarcerated offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22, 134–144. doi: 10.1080/13218719.2014.919689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huizenga HM, Crone EA, & Jansen BJ (2007). Decision-making in healthy children, adolescents and adults explained by the use of increasingly complex proportional reasoning rules. Developmental Science, 10, 814–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen EL, & Metsger LK (1994). A test of the deterrent effect of legislative waiver on violent juvenile crime. Crime & Delinquency, 40, 96–104. doi: 10.1177/0011128794040001007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Xiao L, Palmer P, Sun P, Wang Q, Wei Y, & Bechara A (2008). Affective decision-making deficits, linked to a dysfunctional ventromedial prefrontal cortex, revealed in 10th grade Chinese adolescent binge drinkers. Neuropsychologia, 46, 714–726. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUR0PSYCH0L0GIA.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2017, H.R. 1809, 115th Cong (2017). Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1809

- Kerr A, & Zelazo PD (2004). Development of “hot” executive function: The children’s gambling task. Brain and Cognition, 55, 148–157. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00275-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D, & Levitt SD (1999). Using sentence enhancements to distinguish between deterrence and incapacitation. Journal of Law & Economics, 42(S1), 343–363. doi: 10.1086/467428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS (2006). Examining the divergence across self-report and official data sources on inferences about the adolescent life-course of crime. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22, 107–129. doi: 10.1007/s10940-006-9004-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Dansereau DF, Becan JE, Rowan GA, & Flynn PM (2015). Effectiveness of a theoretically-based judgment and decision making intervention for adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1024–1038. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0127-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kully-Martens K, Treit S, Pei J, & Rasmussen C (2013). Affective decision-making on the Iowa Gambling Task in children and adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19, 137–144. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, & Christensen RHB (2017). lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 52(13), 1–26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard NR, Jha AP, Casarjian B, Goolsarran M, Garcia C, Cleland CM, & Massey Z (2013). Mindfulness training improves attentional task performance in incarcerated youth: A group randomized controlled intervention trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, Article 792. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losel F, & Schmucker M (2004). Psychopathy, risk taking, and attention: A differentiated test of the somatic marker hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 522–529. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Weiler BL, & Widom CS (2000). Comparing self-reports and official records of arrests. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16, 87–110. doi: 10.1023/A:1007577512038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May T, & Hough M (2001). Illegal dealings: The impact of low-level police enforcement on drug markets. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 9, 137–162. doi: 10.1023/A:1011201112490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick EM, & Telzer EH (2017). Failure to retreat: Blunted sensitivity to negative feedback supports risky behavior in adolescents. Neuroimage, 147, 381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012).

- Miura H (2009). Differences in frontal lobe function between violent and nonviolent conduct disorder in male adolescents. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 63, 161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the United States Attorney Southern District of New York. (2014). CRIPA investigation of the New York City Department of Correction Jails on Rikers Island. New York, NY: Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/usao-sdny/legacy/2015/03/25/SDNYRikersReport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Overman WH, Frassrand K, Ansel S, Trawalter S, Bies B, & Redmond A (2004). Performance on the IOWA card task by adolescents and adults. Neuropsychologia, 42, 1838–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popma A, & Raine A (2006). Will future forensic assessment be neurobiologic? Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15, 429–444. doi: 10.1016/J.CHC.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor B, & Dalakar J (2003). Poverty in the United States: 2002 (U.S. Census Bureau, Current population reports, P60–222). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter L, Meador-Woodruff JH, & Dalack GW (2004). Neurocognitive measures of prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 68, 65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00086-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, & Koenen KC (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41, 71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper v. Simmons, 541 U.S. 1040 (2005).

- Schmitt WA, Brinkley CA, & Newman JP (1999). Testing Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis with psychopathic individuals: Risk takers or risk averse? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuermann B, Kathmann N, Stiglmayr C, Renneberg B, & Endrass T (2011). Impaired decision making and feedback evaluation in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 41, 1917–1927. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000262X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurman B, Horan WP, & Nuechterlein KH (2005). Schizophrenia patients demonstrate a distinctive pattern of decision-making impairment on the Iowa Gambling Task. Schizophrenia Research, 72, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M, & Puzzanchera C (Eds.). (2014). Juvenile offenders and victims: 2014 national report. Pittsburgh, PA: National Center for Juvenile Justice; Retrieved from https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/nr2014/downloads/chapter6.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MH, Jedd K, & Luciana M (2015). Neural networks involved in adolescent reward processing: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage, 122, 427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DG, Xiao L, & Bechara A (2012). Decision making in children and adolescents: Impaired Iowa Gambling Task performance in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1180–1187. doi: 10.1037/a0026342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TD, Smith BL, & Smithson MM (1995). The relationship between the WISC-III and the WRAT3 in a sample of rural referred children. Psychology in the Schools, 32, 291–295. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, & Casey BJ (2010). A time of change: Behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition, 72, 124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2007). Risk taking in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 55–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28, 78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Graham S, O’Brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, & Banich M (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80, 28–44. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29738596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingroever H, Wetzels R, Horstmann A, Neumann J, & Wagenmakers E-J (2013). Performance of healthy participants on the Iowa Gambling Task. Psychological Assessment, 25, 180–193. doi: 10.1037/a0029929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syngelaki EM, Moore SC, Savage JC, Fairchild G, & Van Goozen SH (2009). Executive functioning and risky decision making in young male offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 1213–1227. doi: 10.1177/0093854809343095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK, & Mericle AA (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 1133–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, Mericle AA, Dulcan MK, & Washburn JJ (2006). Psychiatric disorders of youth in detention. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Umbach R, Berryessa CM, & Raine A (2015). Brain imaging research on psychopathy: Implications for punishment, prediction, and treatment in youth and adults. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43, 295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uy JP, & Galvan A (2017). Acute stress increases risky decisions and dampens prefrontal activation among adolescent boys. NeuroImage, 146, 679–689. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUR0IMAGE.2016.08.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance B, & Fuller GB (1995). Relation of scores on WISC-III and WRAT-3 for a sample of referred children and youth. Psychological Reports, 76, 371–374. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.76.2.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Lucas CP, Fisher P, & Santos L (2002). The voice DISC-IV with incarcerated male youths: Prevalence of disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 314–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson G (1993). Wide Range Achievement Test 3: Administration manual. Wilmington, DE: Jastak Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Bechara A, Grenard LJ, Stacy WA, Palmer P, Wei Y, & Johnson CA (2009). Affective decision-making predictive of Chinese adolescent drinking behaviors. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 15, 547–557. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Koritzky G, Johnson CA, & Bechara A (2013). The cognitive processes underlying affective decision-making predicting adolescent smoking behaviors in a longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, Article 685. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Pan Y, Qu Z, Fang Z, Yang Z, Yang F, & Rao H (2018). Differential effects of real versus hypothetical monetary reward magnitude on risk-taking behavior and brain activity. Scientific Reports, 8(1), Article 3712. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21820-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, & Raine A (2009). Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 174, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yechiam E, Kanz JE, Bechara A, Stout JC, Busemeyer JR, Altmaier EMM, & Paulsen JS (2008). Neurocognitive deficits related to poor decision making in people behind bars. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(1), 44–51. doi: 10.3758/PBR.15.1.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]