Abstract

Background and objectives

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced mass closures of childcare facilities and schools. While these measures are necessary to slow virus transmission, little is known regarding the secondary health consequences of social distancing. The purpose of this study is to assess the proportion of injuries secondary to physical child abuse (PCA) at a level I pediatric trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients at our center was conducted to identify injuries caused by PCA in the month following the statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland. The proportion of PCA patients treated during the Covid-19 era were compared to the corresponding period in the preceding two years by Fisher’s exact test. Demographics, injury profiles, and outcomes were described for each period.

Results

Eight patients with PCA injuries were treated during the Covid-19 period (13 % of total trauma patients), compared to four in 2019 (4 %, p < 0.05) and three in 2018 (3 %, p < 0.05). The median age of patients in the Covid-19 period was 11.5 months (IQR 6.8–24.5). Most patients were black (75 %) with public health insurance (75 %). All injuries were caused by blunt trauma, resulting in scalp/face contusions (63 %), skull fractures (50 %), intracranial hemorrhage (38 %), and long bone fractures (25 %).

Conclusions

There was an increase in the proportion of traumatic injuries caused by physical child abuse at our center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Strategies to mitigate this secondary effect of social distancing should be thoughtfully implemented.

Abbreviations: PCA, physical child abuse; IQR, interquartile range; OSH, outside hospital; ISS, injury severity score; ED, emergency department; JHCC, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center

Keywords: Covid-19, Coronavirus, Physical child abuse, Nonaccidental trauma

1. Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced mass closures of businesses, schools and childcare facilities around the United States, and internationally, in an effort to mitigate the spread of disease. While social distancing measures are beneficial and necessary in slowing transmission of the virus (Lewnard & Lo, 2020), they may have unintended secondary health consequences, especially to vulnerable populations. For families with young children, both self-imposed and government mandated social distancing measures have resulted in increased time in the home setting. Additionally, they have restricted access to childcare arrangements and decreased interfaces with primary care pediatricians, reducing contact with the caretakers and healthcare providers who typically account for the majority of child protective services referrals. These circumstances may increase the risk of family violence, and increased intimate partner violence has been reported (Kelly & Morgan, 2020; Sapien, Thompson, Raghavendran, & Megan Rose, 2020). However, less is known regarding the effects of social distancing measures on physical child abuse.

The purpose of this study is to assess the proportion of injuries secondary to physical child abuse treated at a level I pediatric trauma center in the month following the mandatory statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland during the Covid-19 pandemic. Furthermore, we sought to characterize the demographic and injury profiles of children treated for physical child abuse at our center and to compare them with the corresponding period in the two preceding years. In doing so, we hope to increase awareness of this secondary health consequence of social distancing in hopes that mitigation strategies can be implemented to prevent physical child abuse should similar circumstances arise in the future.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source and study population

This institutional review board approved retrospective study reviewed patients from the Johns Hopkins Pediatric Trauma Registry. The registry is comprised of patients undergoing evaluation and treatment by the pediatric trauma team at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore, Maryland. Johns Hopkins Children’s Center (JHCC) is designated by the Maryland Institute of Emergency Medical Services Systems (MIEMSS) as a level I pediatric trauma center and regional burn center. The center treats over 800 children who are severely injured or burned each year, and services both the city of Baltimore and the surrounding region. Over half of patients treated at the trauma center are African American and most are publicly insured.

The pediatric trauma team consists of pediatric surgeons, emergency medicine physicians, critical care specialists, a multidisciplinary child protection team, and a variety of other healthcare providers focused on pediatric trauma care. Patients are included in the registry if trauma team activation criteria (described in detail below) are met on presentation, if pediatric trauma service consultation is provided during the emergency department (ED) stay or hospital admission, or if the patient is a suspected or confirmed victim of an assault. A trained senior clinical data specialist abstracts the record of every patient in the registry for demographic characteristics, injury profiles, and outcomes.

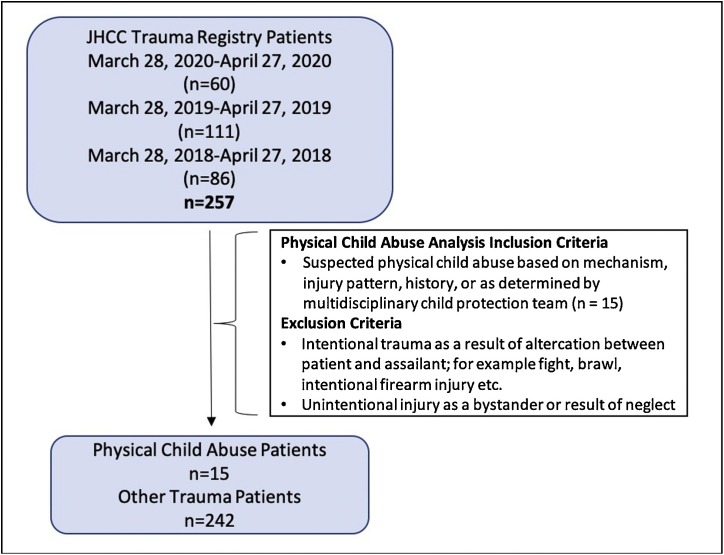

All patients less than 15 years of age in the institutional trauma registry were considered for inclusion (Fig. 1 ). The study period of interest was one month following the statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland, which occurred on the evening of March 27, 2020. Therefore, patients admitted from March 28, 2020 to April 27, 2020 were included. For the sake of comparison, data on patients treated over the same time period in 2019 and 2018 were collected.

Fig. 1.

Patient selection criteria. Patients <15 years of age who were entered into the trauma registry at our pediatric trauma center were considered for inclusion. The study period included the month following the statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland, and the corresponding period in the preceding two years. JHCC, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.

The period of study was chosen based on our target study population. The majority of patients treated for injuries sustained by physical child abuse both at our center and as reported in the literature are infants and young children (Marek et al., 2018; Pandya et al., 2009). Therefore, we felt it was appropriate to choose a study period that might most affect this population, and the Governor’s order to mandate closure of childcare facilities on March 27, 2020 provided a logical start date. It should be noted that public school closures were initiated about one month before childcare closures but persisted through the end of the study period.

Detailed analysis was performed on patients whose injuries were consistent with physical child abuse, which was defined as intentional use of physical force that resulted in physical injury (Leeb, Paulozzi, Melanson, Simon, & Arias, 2008). All suspected victims of physical child abuse are evaluated by a multidisciplinary child protection team. The assessment of the child protection team is based on injury patterns and mechanism, and only cases that are deemed highly specific or diagnostic for physical child abuse are recorded as such in the trauma registry. Victims of intentional trauma resulting from an altercation between the patient and an assailant, such as a fight, brawl, or intentional firearm injury, were not considered physical child abuse. Similarly, those who sustained an unintentional injury as a bystander to an assault directed at another individual were not considered physical child abuse. Finally, for consistency with the objective of this study, victims of sexual abuse or child neglect without inflicted injury were excluded from the analysis entirely.

2.2. Demographics and initial hospital evaluation

Demographic and initial hospital evaluation data were collected on patients identified to have sustained an injury secondary to physical child abuse. Demographic data including age in months, sex, race, and payer status were obtained for each patient, and median, interquartile range (IQR) and percentage calculations were performed where appropriate.

Initial hospital evaluation including patient origin, trauma response level, and emergency department disposition were determined. Patient origin was classified as home/scene of injury when the first medical evaluation occurred at JHCC, or transfer from an outside hospital (OSH) when JHCC served as a tertiary referral center. Trauma response level was reported as the level of trauma team activation in the emergency department upon patient arrival or first evaluation, as dictated by institutional protocol. Level 1 trauma team activation occurs when prehospital information or triage assessment indicates that there is a high likelihood of life-threatening injuries – patients with level 1 activation have evidence of systemic shock, respiratory distress, or severely depressed mental status. Additionally, specific injuries that may require immediate surgical care such as large burns or penetrating injuries to the head, neck, or trunk are activated as level 1. Level 2 responses are activated for patients with moderately depressed mental status or relatively serious mechanism or detected injuries without profound systemic physiologic response. Patients who do not meet trauma team activation criteria are evaluated by pediatric emergency medicine physicians with possible subsequent consultation from the trauma surgery service.

Emergency department disposition was either discharge to home with a safety plan as determined by child protective services, discharge to immediate foster care, or admission to the surgical floor or pediatric intensive care unit.

2.3. Injury characteristics and outcomes

Rates of injured patients secondary to physical child abuse as a proportion of total trauma patients were calculated for the Covid-19 period and the corresponding periods in 2019 and 2018. Diagnosed injuries were identified based on chart review of imaging results, documentation of physical examination findings, and operative reports. Mechanism of injury was classified as blunt, burn, or penetrating trauma. Body region involvement was catalogued as head, extremity, and/or trunk. Using diagnosed injuries and body region involvement, the injury severity score (ISS) was calculated in standard fashion (Marcin & Pollack, 2002). When the injury required operative intervention, this was also captured. Finally, total hospital length of stay and final disposition (home/foster care, rehabilitation, mortality) were recorded.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The ratio of patients with injuries sustained by physical child abuse, as a proportion of all trauma patients, treated during the Covid-19 period were compared to the corresponding periods in the prior two years by Fisher’s exact testing. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata version 15 (StataCorp 2017, College Station, TX). The significance level was set at a p value of less than 0.05.

Comparison of demographics, initial hospital evaluation, injury profiles, and outcomes across periods is provided; however, because of the small number of patients studied, any significant differences were thought to more likely represent statistical anomalies rather than clinically relevant distinctions. Therefore, comparative statistical analysis was not performed for these variables.

3. Results

3.1. Study cohort and rates of physical child abuse

Of the 257 patients in the trauma registry during the study period, 15 were identified as victims of physical child abuse. The proportion of patients treated for injuries sustained by physical child abuse was significantly higher during the Covid-19 period compared to the prior two years (Table 1 ). Eight patients with physical child abuse injuries were treated during the Covid-19 period (13 % of total trauma patients), compared to four in 2019 (4 % of total trauma patients, p value 0.029) and three in 2018 (3 % of total trauma patients, p value 0.022). The proportion of patients treated during the Covid-19 period was also higher when compared to the combined data for 2019 and 2018 (Covid-19: 13 %, 2018/2019: 3.6 %, p value 0.009)

Table 1.

Percentage of total trauma patients, demographic characteristics, and initial evaluation of patients treated for physical child abuse during the month following statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the corresponding period in 2019 and 2018. * indicates significance with p value <0.05.

| Covid-19 Period | 2019 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 8 | n = 4 | n = 3 | |

| % of total trauma patients* | 13 % | 4 % | 3 % |

| Age, median (IQR), months | 11.5 (6.8–34.5) | 10 (3.5-17.8) | 21 (16.0-31.0) |

| Sex, % male | 38 | 50 | 100 |

| Race | |||

| White | 2 (25 %) | 1 (25 %) | 2 (67 %) |

| Black | 6 (75 %) | 3 (75 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 1 (13 %) | 1 (25 %) | 2 (67 %) |

| Public | 6 (75 %) | 3 (75 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Uninsured | 1 (13 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Patient origin | |||

| Home/Scene of injury | 4 (50 %) | 3 (75 %) | 3 (100 %) |

| Transfer from OSH | 4 (50 %) | 1 (25 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Initial Trauma Response | |||

| Level 1 activation | 1 (13 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Level 2 activation | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Trauma Consultation | 5 (63 %) | 4 (100 %) | 2 (67 %) |

| ED Response only | 2 (25 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| ED Disposition | |||

| Home | 2 (25 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Foster care | 1 (13 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Surgical Floor | 3 (38 %) | 2 (50 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Pediatric Intensive Care Unit | 2 (25 %) | 2 (50 %) | 1 (33 %) |

During the Covid-19 period, the median age of patients with injuries secondary to physical child abuse was 11.5 months (IQR 6.8–34.5). Males made up 38 % of those patients. Physical child abuse patients were predominantly black (75 %) with public health insurance (75 %) (Table 1).

3.2. Initial hospital evaluation of patients treated in the Covid-19 period

Our trauma center was the point of initial medical evaluation for half of physical child abuse patients treated in the Covid-19 period, whereas the other half were transferred to our center from another hospital (Table 1). Most patients were initially evaluated by the emergency medicine team with subsequent formal trauma service consultation (63 %), while one patient (13 %) warranted level 1 trauma team activation and two patients (25 %) were evaluated by the emergency medicine team alone. Emergency department disposition was variable with two patients discharged to home with a safety plan as determined by child protective services (25 %), one patient discharged to immediate foster care (13 %), three patients admitted to the surgical floor (38 %), and two patients requiring admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (25 %).

3.3. Injury patterns and outcomes of patients treated in the Covid-19 period

Blunt trauma was the mechanism of injury for all physical child abuse patients treated during the Covid-19 period (Table 2 ). Seven of the eight patients sustained head trauma and two sustained trauma to the extremity. Patients were diagnosed with a number of injuries including face/scalp contusion (63 %), skull fracture (50 %), intracranial hemorrhage (38 %), and long bone fracture (25 %). The average ISS for patients with these injuries was 7.1 (range 1–17). No patients required operative intervention, and the average length of stay was 2.5 days (range 1–6). All patients were discharged to the home/foster care setting.

Table 2.

Injury patterns and outcomes in physical child abuse patients during the month following statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the corresponding period in 2019 and 2018. ISS, injury severity score.

| Covid-19 Period | 2019 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 8 | n = 4 | n=3 | |

| Trauma Mechanism | |||

| Blunt | 8 (100 %) | 3 (75 %) | 2 (68 %) |

| Burn | 0 (0 %) | 1 (25 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Diagnosed Injuries | |||

| Intracranial Hemorrhage | 3 (38 %) | 2 (50 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Skull fracture | 4 (50 % | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Long bone fracture | 2 (25 %) | 1 (25 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Partial thickness burn | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Full thickness burn | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Scalp or face contusion | 5 (63 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Body region | |||

| Head | 7 (88 %) | 2 (50 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Extremity | 2 (25 %) | 2 (50 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| Trunk | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (33 %) |

| ISS, mean (range) | 7.1 (1–17) | 10.3 (10-11) | 10.5 (10-11) |

| Operative intervention | 0 (0 %) | 2 (50 %) | 0 (0%) |

| Length of Stay, mean (range), days | 2.5 (1–6) | 8.0 (4–15) | 1.7 (1–3) |

| Final disposition | |||

| Home/Foster care | 8 (100 %) | 3 (100 %) | 3 (100 %) |

4. Discussion

In this early report of physical child abuse during the Covid-19 pandemic, our data demonstrate an increase in the proportion of physical child abuse patients treated at a level I pediatric trauma center in the immediate period following the statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland. This was notably due to both an increase in the incidence of physical child abuse injuries and a reduction in overall trauma patients treated at our center. While social distancing measures and movement restrictions are justifiably mandated, they appear to have previously unrecognized secondary health consequences. In particular, vulnerable populations such as young children may be at increased risk for harm as parents struggle to accommodate to these unprecedented circumstances.

While not formally demonstrated prior to this study, the theoretical increased risk of physical child abuse during this period has been suggested in the scientific literature (Campbell, 2020; Peterman et al., 2020) and the lay press (Agrawal, 2020; Santhanam, 2020). Quarantines and social isolation have been previously linked to increases in child maltreatment and family violence (Peterman et al., 2020). In particular, evidence suggests that violence against children increases with school closures (Cluver et al., 2020) and in the summer season (Leaman, Hennrikus, & Nasreddine, 2017), when schools are normally not in session. Our data would suggest that a similar pattern exists for young infants and toddlers during periods of childcare facility closure. In the case of Covid-19, this is likely due to increased exposure to perpetrators of violence against children in the home as well as restricted access to safe alternative childcare arrangements. As families struggle to replace reliable professional and informal childcare arrangements, children may be placed under the supervision of less capable caregivers for longer periods of time, which may increase the risk of physical child abuse. In contrast, weekends have been correlated with reduced physical child abuse cases (Bullock, Koval, Moen, Carney, & Spratt, 2009), suggesting that brief periods without formal childcare might not have the same impact as the prolonged period studied here.

In addition to the loss of childcare arrangements during the Covid-19 pandemic, economic insecurity and poverty related stress have increased with the international and local suspension of business and commerce. Economic insecurity has been temporally linked to physical child abuse, with income loss and housing hardship most strongly correlated with child maltreatment (Conrad-Hiebner & Byram, 2020). Specifically relating to the history of economic downturns in the United States, significant increases in physical child abuse were observed during the 2008 recession (Berger et al., 2011; Jordan, MacKay, & Woods, 2017; Shanahan, Zolotor, Parrish, Barr, & Runyan, 2013). During the study period, the unemployment rate in the state of Maryland rose to a record high 9.9 %, with nearly 350,000 new jobless claims filed (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Additionally, although measures of socioeconomic status were limited in our dataset, most patients who suffered injuries as a result of physical child abuse at our center had either public insurance or were uninsured entirely, indicating a relative level of economic insecurity in the household (Casey et al., 2018). However, we were limited in assessing the degree of economic strain caused by the Covid-19 pandemic specifically to our patient’s families. To mitigate the economic effects of Covid-19, federal cash transfer programs have been enacted. Similar programs have led to reduced child maltreatment in other settings (Peterman, Neijhoft, Cook, & Palermo, 2017; Thompson, 2014), but it is unclear whether those results are generalizable to protecting young children during the unprecedented Covid-19 period.

Along with the increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries during the Covid-19 pandemic observed at our center, isolation and social distancing measures may reduce recognition of related injuries in the community. More than two thirds of cases of child abuse and neglect are initially recognized and reported by educational personnel, social services staff, and medical personnel who are likely to have more limited contact with children during the Covid-19 pandemic (US Department of Health & Human Services; Administration for Children & Families, 2019). With reduced exposure to these services, there is widespread concern that victims of child maltreatment are going undetected, and that as social distancing measures are relaxed, a surge of newly diagnosed victims of physical child abuse will emerge (Agrawal, 2020; Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Green, 2020; Santhanam, 2020; Sapien, Thompson, Raghavendran, & Rose., 2020). In our city alone, overall reports of maltreatment to child protective services have been reduced by approximately 60 % since the Covid-19 pandemic began (Baltimore Child Protective Services, personal communication, May 2020). While under detection of physical child abuse cases may be further exacerbated by reluctance to seek evaluation for fear of contracting Covid-19 in the medical environment, the patients in this study were diagnosed with injuries that necessitated hospital-level evaluation and treatment, and in half of instances required transfer to a tertiary pediatric center. Thus, we suspect our methodology is less prone to under-detection. However, it is certainly possible, and equally as troubling, that a large group of patients might be sustaining less severe injuries that are not being evaluated by healthcare providers. We were unfortunately unable to assess the volume and proportion of less severe physical child abuse injuries since they might not have required treatment at our level I trauma center.

Overall, the demographic and injury profiles of the physical child abuse patients treated at our trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic did not differ from the comparison groups of the preceding two years. Furthermore, the population described here is similar to that reported in the literature with more than half of patients being less than one year of age with public health insurance (Yu et al., 2018). Collectively, this information shows that while physical child abuse patients make up a larger percentage of total trauma patients during the Covid-19 pandemic, risk factors and injury patterns may be unchanged.

Although formal reporting on physical child abuse during the Covid-19 pandemic is limited, several others have brought attention to the potential for increases in family violence during this period (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Campbell, 2020; Peterman et al., 2020; Usher, Bhullar, Durkin, Gyamfi, & Jackson, 2020). Media and anecdotal reports of increased intimate partner violence have emerged around the world (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020). These have mainly described an increased volume of calls to domestic violence hotlines (Graham-Harrison, Giuffrida, Smith, & Ford, 2020; Kelly & Morgan, 2020). The underlying reasons for potential increases in intimate partner violence have been cited as social isolation, reduced opportunities to escape abusive partners, and loss of alternative accommodation opportunities, peer support, and mentoring services (Bradbury-Jones & Isham, 2020; Campbell, 2020; Usher et al., 2020). Additionally, alcohol use in the home has been linked to both intimate partner violence and physical child abuse (Curtis et al., 2019). With the closure of bars and restaurants during Covid-19, alcohol sales for consumption in the home have increased (Bremner, 2020), and therefore may contribute to increased family violence. Whether or not these anecdotal reports translate to physical child abuse is undetermined.

This study is limited by the short period of retrospective review, and thus by the small number of patients included. After noting an immediate increase in the proportion of physical child abuse cases treated at our center after the statewide closure of childcare facilities, we felt a sense of urgency to publish this data to increase awareness amongst healthcare providers, policymakers, and families. Both regional and nationwide data over several additional months will need to be compiled to determine if the Covid-19 pandemic is broadly associated with increased physical child abuse with more certainty. Additionally, as social distancing measures are relaxed, this report should increase vigilance to identify victims of child maltreatment who went undetected during the period of study. Furthermore, long-term follow-up was limited due to the time sensitive nature of this study. While we were able to follow all patients through their hospital discharge and short term follow up, we were unable to assess for any long-term morbidities associated with their injuries.

As with most studies of physical child abuse, correctly identifying patients can be challenging, especially through a retrospective chart review. By closely studying injury patterns, described histories, and review by a multidisciplinary pediatric trauma team, we were able to identify injuries consistent with physical child abuse with a high level of certainty. Despite our confidence that the patients reported here did sustain nonaccidental trauma, there may have been other patients at our center who were either not included in the trauma registry or were mistakenly misclassified as sustaining injuries from accidental trauma, thus underrepresenting the true incidence of physical child abuse. In particular, older patients with only cutaneous injuries are not typically included in the trauma registry, which may explain the predominance of infants and toddlers in this study.

Finally, the results of this study must be interpreted in the context of changing baseline rates of traumatic injuries during the Covid-19 pandemic. The increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries seen in this study is due to both an increase in the number of physical child abuse cases, and a reduction in the number of all traumatic injuries treated at our center. Reporting on pediatric trauma overall during the Covid-19 pandemic has been variable, with some centers showing increased injuries while others have seen a reduction in total cases similar to our center (Sugand et al., 2020; Williams, Chrisco, Nizamani, & King, 2020; Williams, Winters, & Cooksey, 2020). Therefore, further research is needed to determine if physical child abuse incidence is truly increasing during the Covid-19 period, or simply failing to see the same reduction that has occurred with other traumatic injuries.

5. Conclusions

In summary, during the period following the statewide closure of childcare facilities in Maryland, there was an increase in the proportion of traumatic injuries caused by physical child abuse treated at our level I pediatric trauma center. While mandated social distancing measures are necessary to reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus, they may have unintended health consequences. Strategies to mitigate these secondary effects should be thoughtfully designed and implemented with special consideration to reducing physical child abuse.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Agrawal N. New York Times; 2020. The coronavirus could cause a child abuse epidemic.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/opin p. Available: [Google Scholar]

- Berger R.P., Fromkin J.B., Stutz H., Makoroff K., Scribano P.V., Feldman K.…Fabio A. Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: A multicenter analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):637–643. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Isham L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;19:1–3. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner J. Newsweek; 2020. U.S. Alcohol sales increase 55 percent in one week amid coronavirus pandemic.https://www.newsweek.com/us-alcohol-sal p. Available: [Google Scholar]

- Bullock D.P., Koval K.J., Moen K.Y., Carney B.T., Spratt K.F. Hospitalized cases of child abuse in America: Who, what, when, and where. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2009;29(3):231–237. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31819aad44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics . US Department of Labor; 2020. State employment and unemployment – April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7127800/pdf/main.pdf Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J.A., Pollak J., Glymour M., Mayeda E.R., Hirsch A.G., Schwartz B.S. Measures of SES for electronic health record-based research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;54(3):430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L., Lachman J.M., Sherr L., Wessels I., Krug E., Rakotomalala S.…McDonald K. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395(10231) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad-Hiebner A., Byram E. The temporal impact of economic insecurity on child maltreatment: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2020;21(1):157–178. doi: 10.1177/1524838018756122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A., Vandenberg B., Mayshak R., Coomber K., Hyder S., Walker A.…Miller P.G. Alcohol use in family, domestic and other violence: Findings from a cross-sectional survey of the Australian population. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2019;38(4):349–358. doi: 10.1111/dar.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Harrison E., Giuffrida A., Smith H., Ford L. The Guardian; 2020. Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence.https://www.theguardian.com/society/202 Available: [Google Scholar]

- Green P. Risks to children and young people during covid-19. British Medical Journal. 2020;369(1669) doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1669. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K.S., MacKay P., Woods S.J. Child maltreatment: Optimizing recognition and reporting by school nurses. NASN School Nurse. 2017;32(3):192–199. doi: 10.1177/1942602X16675932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J., Morgan T. BBC News; 2020. Coronavirus: Domestic abuse calls up 25% since lockdown, charity says.https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-52157620 Available. [Google Scholar]

- Leaman L., Hennrikus W., Nasreddine A.Y. An evaluation of seasonal variation of nonaccidental fractures in children less than 1 year of age. Clinical Pediatrics. 2017;56(14):1345–1349. doi: 10.1177/0009922816687324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb R.T., Paulozzi L.J., Melanson C., Simon T.R., Arias I. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2008. Child maltreatment surveillance: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewnard J.A., Lo N.C. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;3099(20):2019–2020. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcin J.P., Pollack M.M. Triage scoring systems, severity of illness measures, and mortality prediction models in pediatric trauma. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30(11 SUPPL):457–467. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek A.P., Nygaard R.M., Cohen E.M., Polites S.F., Sirany A.M.E., Wildenberg S.E.…Richardson C.J. Rural versus urban pediatric non-accidental trauma: Different patients, similar outcomes. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3639-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya N.K., Baldwin K., Wolfgruber H., Christian C.W., Drummond D.S., Hosalkar H.S. Child abuse and orthopaedic injury patterns: Analysis at a level I pediatric trauma center. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2009;29(6):618–625. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181b2b3ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., Neijhoft A.N., Cook S., Palermo T.M. Understanding the linkages between social safety nets and childhood violence: A review of the evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning. 2017;32(7):1049–1071. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., Potts A., Donnell M.O., Shah N., Oertelt-prigione S., Van Gelder N.…Thompson K. The Center for Global Development; 2020. Working paper 528 April 2020 pandemics and violence against women and children. [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam L. PBS News Hour; 2020. Why child welfare experts fear a spike of abuse during COVID-19.https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/why p. Available: [Google Scholar]

- Sapien J., Thompson G., Raghavendran B., Rose M. ProPublica; 2020. Domestic violence and child abuse will rise during quarantines. So will neglect of at-risk people, social workers say.https://www.propublica.org/article/dome Available. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan M.E., Zolotor A.J., Parrish J.W., Barr R.G., Runyan D.K. National, regional, and state abusive head trauma: Application of the CDC algorithm. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugand K., Park C., Morgan C., Dyke R., Aframian A., Hulme A.…COVERT Collaborative Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric orthopaedic trauma workload in central London: A multi-centre longitudinal observational study over the “golden weeks”. Acta Orthopaedica. 2020 doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1807092. Article In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. Cash transfer programs can promote child protection outcomes. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2014;38(3):360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services; Administration for Children and Families . Child Welfare Information Gateway; Washington: 2019. Child maltreatment 2017: Summary of key findings. [Google Scholar]

- Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. Family violence and COVID‐19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2020 doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. Epub ahead. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams F.N., Chrisco L., Nizamani R., King B.T. COVID-19 related admissions to a regional burn center: The impact of shelter-in-place mandate. Burns Open. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x.Bizzarro. Article In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams N., Winters J., Cooksey R. Staying home but not out of trouble: No reduction in presentations to the South Australian paediatric major trauma service despite the COVID ‐19 pandemic. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ans.16277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.R., DeMello A.S., Greeley C.S., Cox C.S., Naik-Mathuria B.J., Wesson D.E. Injury patterns of child abuse: Experience of two Level 1 pediatric trauma centers. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2018;53(5):1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]