Abstract

Background:

The uptake of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) has been slow among people living with HIV (PLWH).

Methods:

We surveyed adults recently diagnosed with HIV in 14 South African primary health clinics. Sixteen potential barriers and facilitators related to preventive therapy among PLWH were selected based on the literature review and qualitative interviews. Best-worst scaling (BWS) was used to quantify the relative importance of the attributes. BWS scores were calculated based on the frequency of participants’ selecting each attribute as the best or worst among six options (across multiple choice sets) and rescaled from 0 (always selected as worst) to 100 (always selected as best) and compared by currently receiving IPT or not.

Results:

Among 342 patients surveyed, 33% (n=114) were currently taking IPT. Having the same standard of life as someone without HIV was most highly prioritized (BWS score=67.3, SE=0.6), followed by trust in healthcare providers (score=66.3±0.6). Poor standard of care in public clinics (score=30.6±0.6) and side effects of medications (score=33.7±0.6) were least prioritized. BWS scores differed by IPT status for few attributes, but overall ranking was similar (spearman’s rho=0.9).

Conclusion:

Perceived benefits of preventive therapy were high among PLWH. IPT prescription by healthcare providers should be encouraged to enhance IPT uptake among PLWH.

Keywords: choice experiment, isoniazid preventive therapy, patient preferences

Introduction

About 1.7. billion individuals are estimated to be latently infected with tuberculosis (TB) in 2014 [1], and 1.5 million deaths occurred due to active TB in 2016 – the highest burden due to an infectious disease [2]. In South Africa, there are 7 million people living with HIV, consisting of large pool of people to potentially reactivate latent TB infection (LTBI) to active TB [2]. People living with HIV (PLWH) have a 20-fold higher risk of developing active TB from LTBI thus identifying and treating LTBI is a crucial part of effective TB control among PLWH [3].

Isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT), the provision of daily isoniazid (INH) for at least 6 months, has been shown to reduce TB incidence by up to 60% among PLWH [4–6]. Recently, new shorter drug regiments such as a weekly dose of rifapentine and isoniazid for 3 months have been recommended as effective options for TB preventive treatment [7]. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended provision of IPT to PLWH since 2011 [8], only 15 of the 30 high burden TB/HIV countries reported any provision of TB preventive treatment to HIV-positive people in 2018 [7]. South Africa has been the leading country to provide TB preventive treatment, but the coverage rate is still sub-optimal at 56% [7].

Barriers and facilitators for IPT uptake have been identified at the patient, provider and health systems levels [9,10]. Fear of side effects, non-disclosure of HIV status or competing socioeconomic responsibilities are associated with a lower rate of IPT uptake and retention in care among PLWH [11]. Providers often do not receive sufficient training to implement new guidelines or may prioritize prescription of antiretroviral therapy (ART) over IPT [12]. Frequent IPT stock-out or lack of transportation to clinics also impedes initiation and adherence to IPT [13].

There are limited studies on how patients recently diagnosed with HIV perceive and prioritize different factors and make a decision regarding uptake of preventive therapy. We sought to quantify the relative importance of 16 factors related to preventive therapy (including IPT) among individuals recently diagnosed with HIV. The findings of this study are relevant to policy makers and healthcare providers who aim to design and implement effective programs for linkage to care for preventive therapy in high HIV/TB burden settings.

Methods

Study population and setting

This study was conducted at 14 public primary care clinics in the Dr. Kenneth Kaunda health district in North West province, South Africa from November 2014 to December 2015. The study was nested within an ongoing cluster randomized trial, which compares the impact of two different diagnostic tests for latent TB infection on the proportion of IPT initiation among newly diagnosed HIV patients in these 14 clinics [14,15]. Clinics were selected to represent a range of clinic hours, patient volumes, urban vs rural setting, and geographic locations. Patients were eligible for enrolment if they were ≥18 years old, and diagnosed with HIV in the preceding six months. The study personnel unrelated to the local clinics recruited and enrolled the participants. Since the survey included reading choice tasks, patients were asked to read a sample sentence in English, Xhosa, Setswana, or Zulu, and only those who were able to read were enrolled after written informed consent was obtained. In this community, the literate rate among adults was 94% [16]. Majority of the respondents (82%) chose to complete the English version of questionnaire. All interviews were conducted in a private room in the clinic to ensure patients’ confidentiality. Interviewers administered the overall questionnaire. The study participants were asked to read each of the best-worst scaling (BWS) choice tasks at their own pace, which was shown in a A4-size flashcard by the interviewer, and report their choices to the interviewer. The study was approved by institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the University of Witwatersrand.

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey using an object case best-worst scaling (BWS) instrument. BWS is a stated-preference method based on the assumption that a respondent is a rational choice maker to maximize their utility and can choose the best (most important) and the worst (least important) attribute from a set of available options in a given choice task [17–20]. Choice experiments including BWS were developed in marketing and transportation research but have been widely used in health service research to elicit patients’ perspectives and preferences for health interventions and treatments [21,22]. Of three variants of BWS, object case BWS allows to estimate the relative importance of attributes in a continuous quantitative scale [23].

Selection of attributes

We followed the framework for instrument development of a choice experiment in order to identify and refine the tested attributes [20]. First, we carried out a literature review on barriers and facilitators regarding uptake of preventive therapies including ART [10,11,15,24]. In-depth interviews were conducted among 56 PLWH and healthcare providers to elicit patients’ experience and perceptions of ART and IPT as part of the parent study in the 14 clinics [15]. We sought to identify attributes likely to influence HIV-positive individuals’ decision-making for uptake of preventive therapy at individual, interpersonal, community and health systems levels using a social ecological model [25]. A total of 16 attributes were selected which represented roughly equal numbers of both barriers and facilitators to uptake of preventive therapy and converted to simple statements. The statements were reviewed by stakeholders and pre-tested by research staff, and health providers and a random selection of patients in the study clinics. Based on the feedback, we added the following in the vignette: “the statement you agree with the most” to clarify the meaning of choosing the statement which best describes respondents’ thoughts and “the statement you disagree with the most” for choosing the statement worst describing their thoughts. The final design was pilot-tested among the first 30 enrolled patients to evaluate acceptability and content-validity (Table 1).

Table 1.

16 tested attributes related to preventive therapies tested in the best-worst scaling task

| Attributes | Statements |

|---|---|

| Strength | Medications to prevent disease help me feel stronger. |

| Prevention for illness | I can avoid getting serious illnesses that are common for people with HIV. |

| Benefits of medication | The benefits of medication are greater than the harms. |

| Knowledge on pill purpose | I know the purpose of each different medication that I take. |

| Difficulty in daily adherence | I have trouble taking medication on a daily basis. |

| Pill burden | I don’t want to take a lot of pills every day. |

| Side effects | All medicines have some side effects. |

| Normalization of preventive therapy | Lots of people with HIV take preventive treatments. |

| Family responsibility | My family needs me to take care of them now and in the future. |

| Same standard of life | People with HIV can have the same standard of life as someone without HIV. |

| Long life | People with HIV can live a long time if they take care of themselves. |

| Fear of HIV disclosure to family | I am afraid to disclose my HIV status to my family. |

| Fear of unintended HIV disclosure | I worry that taking pills every day tells other people that I have HIV. |

| Trust in healthcare providers | I trust that doctors and nurses know what is best for my health. |

| Poor standard of care | The standard of care in public clinics is poor. |

| Transportation cost | Getting to the clinic costs me too much money. |

Experimental Design

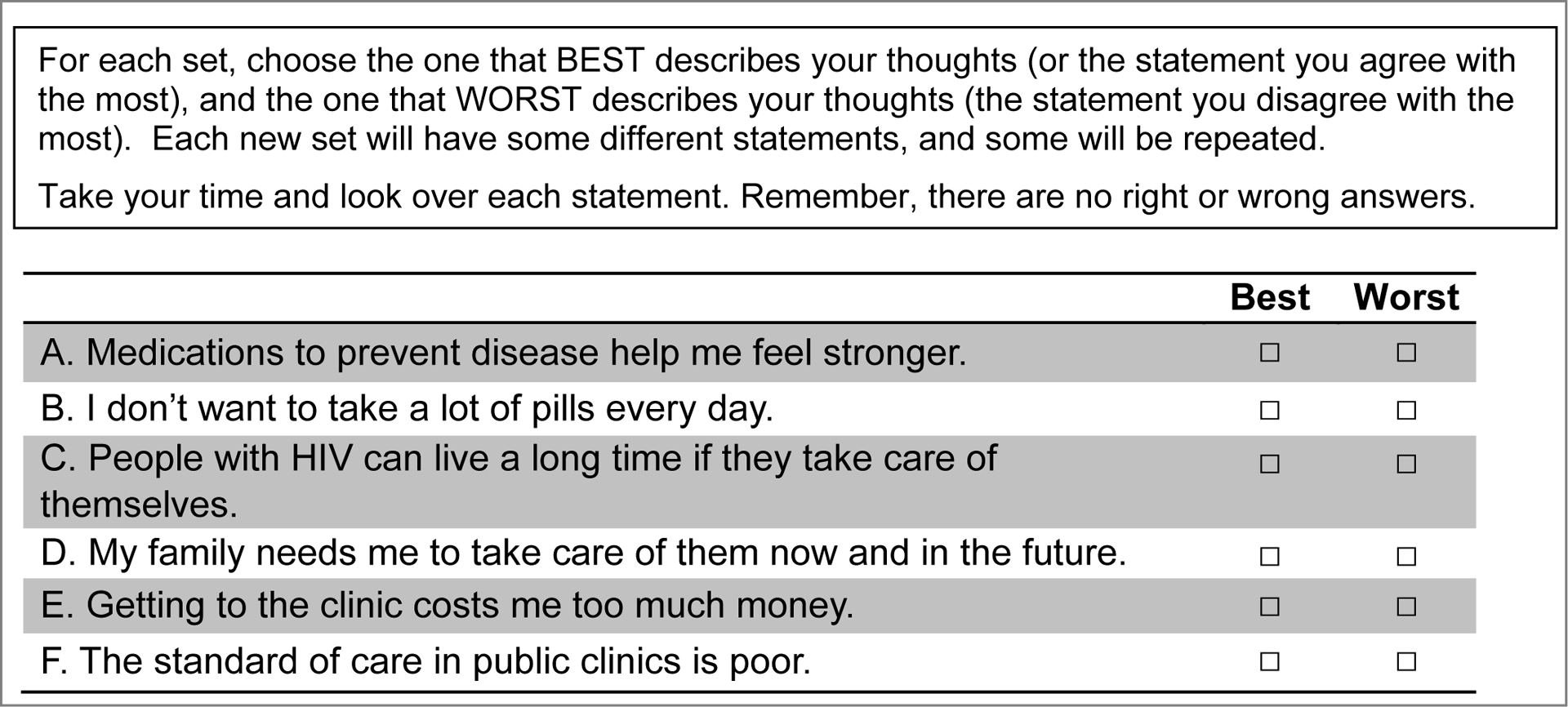

We used a balanced incomplete block design, which allows the repetition of different combinations of statements in the subsets of all possible choice scenarios [26]. The design allows one to estimate utility or preference associated with each statement with an increased precision. Each participant was presented with six statements in each given choice task and asked to choose one statement out of the six that best described their thoughts, as well as the one statement that least described their thoughts. Each of the 16 statements appeared six times across 18 separate choice tasks (Figure 1). Each pair of two statements also appeared twice across the questionnaire. In addition to BWS tasks, we collected socio-demographics and a brief clinical history from each participant.

Figure 1.

Example of a best-worst scaling choice task with six attributes related to preventive therapies among HIV-positive individuals

Data Analysis

The dependent variable was the participants’ choice of the best and worst statement in each subset of statements presented to them [27]. Each statement chosen as best received a score of 100 while the statement chosen as worst received a score of 0 and all other non-selected statements a score of 50 [28]. The aggregate BWS score was calculated as the mean score across all respondents. A BWS score of 50 would mean that overall, either respondents were indifferent to the statement or equally likely selected it as the best or worst statement. We compared BWS scores by each participant’s IPT initiation status at the time of survey (receiving IPT vs. no IPT). We used Spearman’s rho to compare the ranked correlation of the 16 attributes between the two groups. We compared the BWS scores using Wald tests, assuming a null hypothesis of no statistically significant difference by IPT initiation status.

To explore preference heterogeneity among participants, we fitted latent class conditional logit models and estimated the probability of each respondent belonging to each class [29]. We fitted up to five classes and calculated Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to identify the number of classes with the best model fits [30]. Coefficients from the conditional logit models represents the relative degree of preference for attributes in each latent class. In multinomial logistic regression, we examined sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with class membership including age, gender, history of being close to TB patients, IPT status, having disclosed HIV status to any of household members, monthly household income (≤R1000 vs. >R1000; R1000 is equivalent to US $82 in 2015), and having more than two adults living in the household. Factors with p-value < 0.10 were retained and those with p-value <0.05 fitted in the final models. Results are reported with adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All analyses were conducted in STATA 13.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 342 HIV-positive individuals were enrolled and completed the questionnaire (Table 2). The mean age was 34(±10) years, and 65% (n=218) were female. About 33% (n=115) had initiated and were currently receiving IPT, and 56% (n=192) were on ART at enrollment. The mean CD4 count at enrollment was 238 (±211) cells/mm3 in the IPT group, compared to 323 (±208) cells/mm3 in the no IPT group (p<0.001). The average time since HIV diagnosis was longer in the participants receiving IPT (70±77 days) than among those not receiving IPT (35±49 days) (p<0.001). In the IPT group, about 68% (77/114) of the participants had disclosed their HIV status to at least one household member, compared to 50% (114/226) in the no IPT group (p=0.003).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by the current status of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) among 342 HIV-positive individuals, South Africa

| N (%) | On IPT at enrollment (N=115) | No IPT (N=227) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (± SD) | 34 (±10) | 34 (±10) | 0.99 |

| Time since HIV diagnosis, Mean (± SD) (days) | 70 (±77) | 35 (±49) | <0.01 |

| CD4 cell count, Mean (± SD)† | 238 (±211) | 323 (±208) | <0.01 |

| ART status | |||

| Yes | 100 (87.0) | 92 (40.9) | <0.01 |

| No | 15 (13.0) | 133 (59.1) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Full time | 49 (21.7) | 23 (20.0) | 0.04 |

| Part time or piece jobs | 56 (24.8) | 16 (13.9) | |

| Unemployed | 121 (53.5) | 76 (66.1) | |

| Marriage status | |||

| Married | 4 (3.5) | 14 (6.2) | 0.37 |

| Living with partner | 39 (33.9) | 91 (40.4) | |

| Not living with my partner | 36 (31.3) | 63 (28.0) | |

| No current partner | 36 (31.3) | 57 (25.3) | |

| Mode of transportation to clinic | |||

| On foot | 89 (77.4) | 156 (70.0) | 0.06 |

| Public taxi or bus | 25 (21.7) | 53 (23.8) | |

| Private car or motorbike | 1 (0.9) | 14 (6.3) | |

| Transportation cost (Rand) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0, 16) | 0 (0, 15) | 0.86 |

| History of contact to a TB patient | |||

| Yes | 31 (27.0) | 72 (32.0) | 0.55 |

| No | 83 (72.2) | 149 (66.2) | |

| Perceived risk of developing TB within next year | |||

| Very or Moderately likely | 1 (0.9) | 5 (2.2) | 0.26 |

| Slightly likely | 35 (30.4) | 51 (22.6) | |

| It is not at all likely | 79 (68.7) | 170 (75.2) | |

| Disclosure of HIV status to any of household member | |||

| Yes | 77 (67.5) | 114 (50.4) | <0.01 |

| No | 37 (32.5) | 112 (49.6) | |

| Disclosure of HIV status to partner‡ | |||

| Yes | 61 (92.4) | 134 (84.8) | 0.12 |

| No | 5 (7.6) | 24 (15.2) |

Pearson χ2 test (discrete variables), t-test (mean comparison for continuous variables) and Mann-Whitney test (median comparison for continuous variables) were used.

N for on IPT at enrolment and no IPT groups is 111 and 186, respectively.

N shown among those with current partners.

Abbreviation: ART: Antiretroviral therapy; IPT: Isoniazid preventive therapy; TB: Tuberculosis

Attribute prioritization

Having the same standard of life as someone without HIV was most highly prioritized (BWS score=67.3, SE=0.6), followed by trust in healthcare providers (score=66.3±0.6) and living a long life (score=63.4±0.6) (Table 3). Poor standard of care in public clinics (score =30.6±0.6) was prioritized the lowest, followed by side effects of medications (score=33.7±0.6) and fear of unintended disclosure of HIV status to others (score=34.6±0.6). Difficulty of daily adherence to medication (score=43.5±0.5) or pill burden (score=40.9±0.5) were moderately ranked. Transportation cost (score=37.5±0.5) had a lower BWS score as well.

Table 3.

Ranking of 16 statements related to preventive therapies among 342 HIV-positive individuals

| Statement | Best* | Worst† | BWS score | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People with HIV can have the same standard of life as someone without HIV. | 786 | 75 | 67.3 | 0.6 |

| I trust that doctors and nurses know what is best for my health. | 771 | 102 | 66.3 | 0.6 |

| People with HIV can live a long time if they take care of themselves. | 662 | 112 | 63.4 | 0.6 |

| Medications to prevent disease help me feel stronger. | 503 | 88 | 60.1 | 0.5 |

| My family needs me to take care of them now and in the future. | 476 | 101 | 59.1 | 0.5 |

| I can avoid getting serious illnesses that are common for people with HIV. | 578 | 204 | 59.1 | 0.7 |

| I know the purpose of each different medication that I take. | 384 | 93 | 57.1 | 0.5 |

| The benefits of medication are greater than the harms. | 389 | 169 | 55.4 | 0.6 |

| Lots of people with HIV take preventive treatments. | 294 | 181 | 52.7 | 0.5 |

| I have trouble taking medication on a daily basis. | 72 | 337 | 43.5 | 0.5 |

| I don’t want to take a lot of pills every day. | 73 | 447 | 40.9 | 0.5 |

| I am afraid to disclose my HIV status to my family. | 122 | 592 | 38.5 | 0.6 |

| Getting to the clinic costs me too much money. | 55 | 566 | 37.5 | 0.5 |

| I worry that taking pills every day tells other people that I have HIV. | 84 | 714 | 34.6 | 0.6 |

| All medicines have some side effects. | 112 | 783 | 33.7 | 0.6 |

| The standard of care in public clinics is poor. | 94 | 890 | 30.6 | 0.6 |

Number of times chosen as best attribute in a given choice set is calculated. A total of 1,944 (324 respondents × 6 times per attribute) was available to be selected per attribute.

Number of times chosen as worst attribute in a given choice set is calculated.

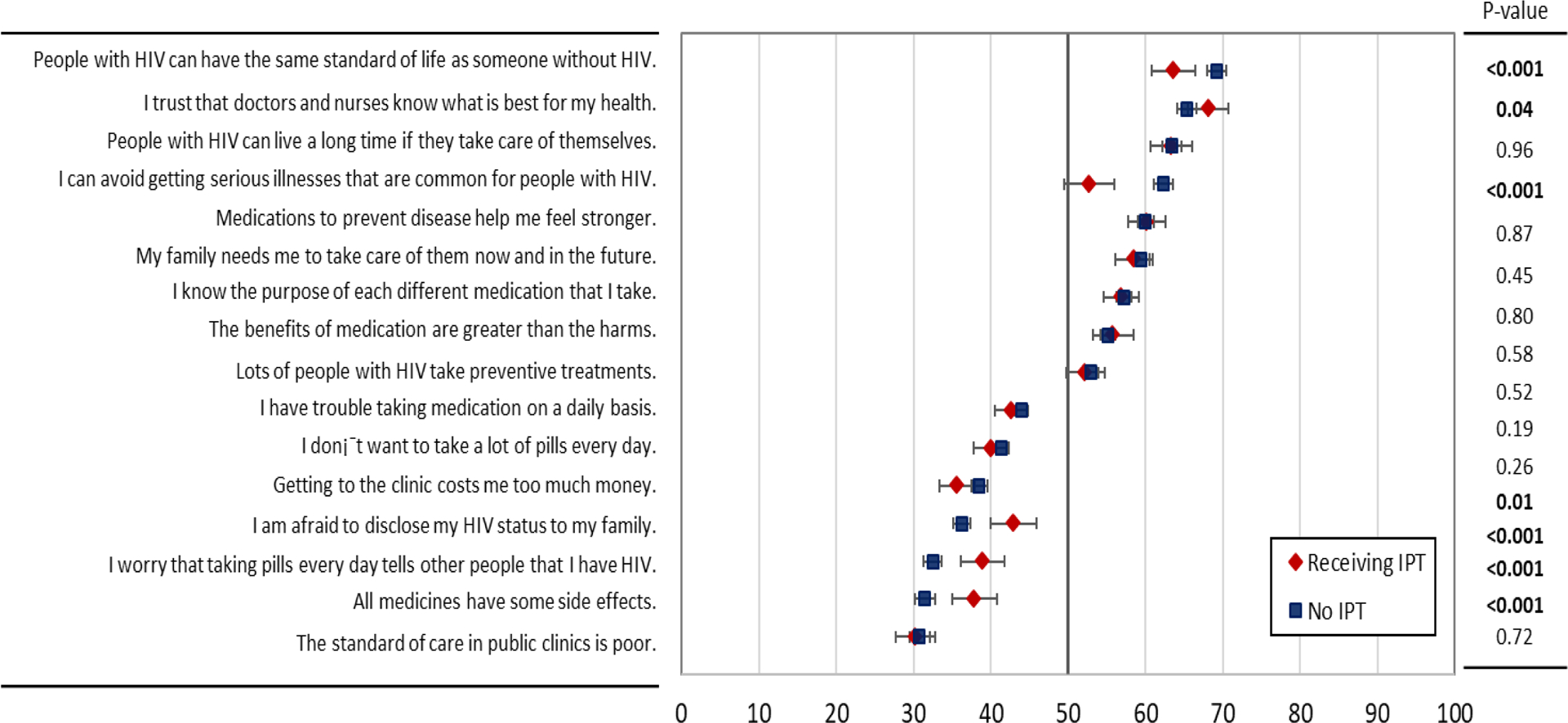

When stratified by IPT status, the overall ranking of the attributes was highly correlated between the two groups, suggesting the relative (ordinal) importance attached to these attributes are strongly correlated (spearman’s rho=0.9). Individuals receiving IPT had a significantly lower score for illness prevention (score=52.8±1.6) compared to those who were not on IPT (score=62.3±0.6, p<0.001) (Figure 2). Those on IPT also had significantly higher BWS scores for fear of unintended HIV disclosure to family (score=42.9±1.5 vs. score=36.3±0.6, p<0.001) and to others (score=38.9±1.5 vs. score=32.5±0.6, p<0.001) compared to those who were not on IPT.

Figure 2. Best-worst scaling (BWS) scores for 16 statements related to preventive therapies among HIV-positive individuals by IPT status.

Red diamonds represent the mean priority score among individuals receiving IPT at enrollment, while blue squares represent the responses of individuals not taking IPT. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals, and p-values from Wald tests comparing mean BWS scores by IPT status are presented to the right

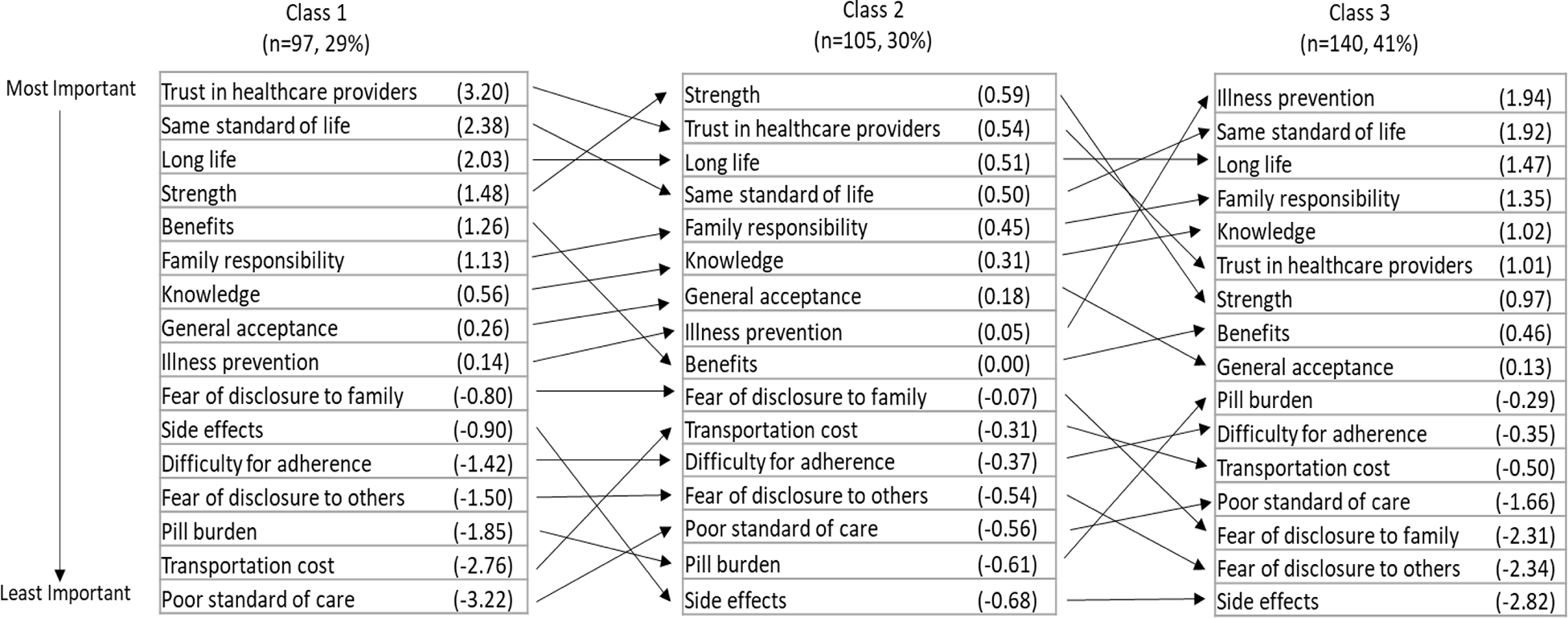

Latent class analysis

Based on the AIC and BIC criteria and the sample size within each class, we identified three classes (Figure 3). The class 1, 2, and 3 included about 29%, 30%, and 41% of participants, respectively. Compared to those in the first class, individuals in the second class membership were more likely to report perceived risk of developing TB within next year (aOR=2.05; 95% CI: 1.02–4.12), be older than 40 years old (aOR=3.05; 95% CI: 1.41–6.61), and have lower household income (aOR=2.52; 95% CI: 1.34–4.76) (Table 4). The third class membership was strongly associated with non-disclosure of HIV status to any of household members (aOR=8.33, 95% CI:4.28–16.23) as well as lower household income (aOR=3.50; 95% CI: 1.70–7.21) and having more than two adults living in the household (aOR=2.42; 95% CI 1.21–4.85). Being male was also associated with the third class membership. While the relative degree of preference for attributes varied across the latent class memberships, the overall ranking of the attributes in class 2 and 3 was highly correlated with that in class 1 (spearman’s rho=0.90 and 0.75, respectively).

Figure 3. Ranking of 16 attributes by coefficients in each latent class.

The number in the parenthesis represent coefficients estimated from the latent conditional logistic regression model. Class 1, 2 and 3 includes 97, 105 and 140 individuals, respectively.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions of latent class 2 and 3 memberships

| Class 2 (vs. Class 1) | Class 3 (vs. Class 1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | aOR* | OR | aOR* | ||

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| <30 | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| 30–39 | 1.27 (0.65–2.45) | 1.08 (0.53–2.20) | 1.01 (0.55–1.85) | ||

| 40+ | 2.83 (1.39–5.77) | 3.05 (1.41–6.61) | 2.22 (1.14–4.33) | ||

| Time since HIV diagnosis (days) | |||||

| <30 | 0.88 (0.47–1.66) | 2.51 (1.34–4.69) | |||

| 30–60 | 0.67 (0.31–1.42) | 0.87 (0.40–1.91) | |||

| 60+ | Ref | Ref | |||

| CD4 cell count (per 100 counts/mm3) | 1.03 (0.89–1.18) | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) | |||

| Sex, Male (vs. Female) | 1.45 (0.79–2.65) | 1.97 (1.12–3.46) | 2.02 (0.97–4.19) | ||

| Employment status | |||||

| Full time | 0.54 (0.26–1.10) | 1.03 (0.55–1.93) | |||

| Part time or piece jobs | 1.29 (0.59–2.82) | 2.49 (1.21–5.10) | |||

| Unemployed | Ref | ||||

| Marriage status | |||||

| Married or living with partner | 1.59 (0.80–3.17) | 1.80 (0.96–3.39) | |||

| Not living with my partner | 1.26 (0.62–2.56) | 0.81 (0.41–1.61) | |||

| No current partner | Ref | Ref | |||

| Number of adults living in the Household, 3+ (vs. 1–2) | 1.54 (0.88–2.68) | 2.06 (1.21–3.49) | 2.42 (1.21–4.85) | ||

| Monthly household income (rand), < 1000 (vs. 1000+) | 2.57 (1.42–4.66) | 2.52 (1.34–4.76) | 2.86 (1.58–5.18) | 3.50 (1.70–7.21) | |

| Mode of transportation to clinic | |||||

| Public taxi or bus | 0.92 (0.47–1.79) | 1.01 (0.55–1.87) | |||

| Private car or motorbike | 2.30 (0.43–12.25) | 2.83 (0.58–13.72) | |||

| On foot | Ref | Ref | |||

| History of contact to a TB patient, Yes (vs. No) | 0.49 (0.26–0.94) | 1.30 (0.75–2.26) | |||

| Perceived risk of developing TB within next year | |||||

| Slightly or more likely | 1.93 (1.02–3.64) | 2.05 (1.02–4.12) | 1.38 (0.74–2.57) | ||

| It is not at all likely | Ref | Ref | |||

| Disclosure of HIV status to any of household member, No (vs. Yes) | 1.05 (0.55–2.02) | 8.33 (4.28–16.23) | |||

| Disclosure of HIV status to partner, No (vs. Yes) | 1.37 (0.49–3.77) | 1.35 (0.52–3.53) | |||

| Currently on IPT at enrolment, Yes (vs. No) | 1.03 (0.59–1.80) | 0.41 (0.23–0.72) | |||

Adjusted for all other covariates shown in the column

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratios; aOR, adjusted odds ratios; TB, tuberculosis; IPT, isoniazid preventive therapy

Discussion

Our study findings suggest that individuals with a recent HIV diagnosis place a higher prioritization on trust in healthcare providers and medication benefits, compared to structural barriers such as transportation costs, when these factors were considered simultaneously. They also highly perceive that people with HIV can have the same standard of life and a long life, compared to those without HIV. BWS methodology has several advantages compared to simple prioritization techniques as it generates more consistent results by allowing only extreme choices rather than ranking or rating all potential options [31]. Such priorities regarding preventive therapy among HIV-positive individuals need to be considered to design and deliver patient-centered care in sub-Saharan Africa.

We observed that patients highly prioritize medication benefits of preventive therapy and trust in health care providers, and very few people considered the standard of care in public clinics as poor. Counseling and education are important parts of increasing patients’ knowledge which influence their decision on initiating and completing treatment [5,32,33]. Other qualitative studies have shown that perceived patient-derived barriers such as lack of money for transport to clinic or pill burden are low when patients have a good understanding of medication benefits [13]. Our study results also emphasize that educating patients about IPT alone would not be sufficient, and it is crucial to simultaneously build trust between health care providers and patients, similar to what we found among HIV-positive pregnant women [34]. Having a favorable relationship with health care providers or trust in the healthcare system have been associated with an increased likelihood of IPT initiation and completion in South Africa and other sub-Saharan countries [9,35].

Difficulty in adherence, pill burden, fear of HIV disclosure to family or transportation cost were among the least prioritized in this study, contradicting other studies where these were identified as major barriers for uptake of ART and/or IPT [10,13,36]. In this study, these were either not chosen or chosen as the worst statement, indicating potentially lower importance of these factors compared to other medication benefits. Participants were all recently diagnosed with HIV (average of 60 days) and had received ART and IPT for about only one month. Thus pill burden and monthly clinic visits were probably not perceived as major barriers yet. In addition, most people received ART as a fixed dose combination tables (one pill per day) which may explain why one additional pill for IPT was well accepted in our study population. Other qualitative studies have also shown that HIV-related stigma was not a specific barrier to IPT especially for those who were already engaged in HIV care [9]. About half of the participants walked to clinic thus participants could have considered the cost of transportation as a minor burden.

We noted some differences in prioritization by IPT status but such differences were relatively minor. Among those who received IPT, fear of HIV disclosure to family or others was more highly prioritized compared to those not receiving IPT. It is important to note that some of the observed differences by IPT status may reflect differences in the corresponding populations; for example, those not on IPT reported significantly shorter time since HIV diagnosis. When we explored the preference heterogeneity using the latent class analysis, the overall ranking of the attributes was similar across the three latent classes despite that the relative degree of preference for attributes varied. Some demographic factors were significantly associated with the class memberships. Notably, the second class membership was associated with lower household income and older age, potentially explaining why transportation cost and gaining strength by taking the medication were considered as more important attributes.

Although individuals in the third class membership were significantly less likely to have disclosed HIV status to household members, more than 80% of the individuals who had partners did so to their partners, and the non-disclosure of HIV status was independently associated with shorter time since HIV diagnosis at the time of enrollment. Thus, this class membership potentially reflects the preferences of those more newly diagnosed (i.e. within a month) who had not had a chance to disclose their HIV status to household members yet, rather than intentionally not disclosing due to fear or social stigma. This might explain why the third class membership ranked the attributes related to disclosure of HIV status relatively low. Being male may have also contributed to the lower likelihood of disclosing HIV status. Overall, all classes highly perceived that people with HIV could have the same standard of life as well as a long life. These findings emphasize the general importance of perceived medication benefits of preventive therapies among newly diagnosed with HIV.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we asked participants to choose between both positive and negative statements in the same choice task. It is possible that positive statements were considered as facilitators of preventive therapy and negative statements as barriers. However, substantial proportions of individuals chose positive statements as the statements “worst” describing their thoughts, and negative statements as “best” describing their thoughts across different choice tasks. For example, the statement “I can avoid getting serious illnesses that are common for people with HIV” was chosen as the best for two-third of the times and as the worst for one-third, supporting that participants likely identified best and worst statements as intended. Second, our methods assume that the importance assigned to the best or worst statement is similar across individuals. To overcome this, we fitted three classes in the latent class analysis but observed largely similar patterns across the classes. Third, although we emphasized to the respondents that participation and responses in the study would not have any effect on receiving their care at the clinics, there could have been social desirability bias on how they responded to the questions related to quality of care or trust in healthcare providers. However, our results are in line with the qualitative findings that patients highly valued the quality of care they received at these clinics [15]. Finally, we caution that our results comparing priorities by IPT status were not intended to reveal a causal relationship and should not be interpreted as such. Future studies to elicit preferences in a longitudinal design are warranted.

Conclusion

We have quantified the perceived priorities for preventive therapies for tuberculosis among HIV-positive individuals in South Africa. We demonstrate that trust in healthcare providers and medication benefits were highly prioritized, while structural barriers and side effects of medications were prioritized the least. These findings illustrate the importance of eliciting and responding to patients’ priorities when attempting to implement interventions that seek to prevent future disease, including IPT. Our results support that IPT prescription would be well accepted by patients and should encouraged and delivered by healthcare providers via enhanced counseling on medication benefits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH supplement R01 AI095041 02S1. We thank all study participants for devoting their time to take part in this study. We thank our study coordinators, Sandy Chon, Cokiswa Quomfo, Mmabatho Malegotsi, Juanita Market, Elvis Rangxa, and Thembekile Mmoledi as well as all study staff who helped in data collection. We also thank all the reviewers who provided valuable insights and comments.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Houben RMGJ Dodd PJ. The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling Metcalfe JZ, editor. PLOS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017. Geneva; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn SD, Churchyard G. Epidemiology of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(4):325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golub JE, Saraceni V, Cavalcante SC, Pacheco AG, Moulton LH, King BS, et al. The impact of antiretroviral therapy and isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson RJ, Boulle A, Glynn JR, Fielding K, van Cutsem G, et al. Isoniazid plus antiretroviral therapy to prevent tuberculosis: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9944):682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organisation. Global Health TB Report [Internet]. Who. 2018. 277 p. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. 2011.

- 9.Jacobson KB, Niccolai L, Mtungwa N, Moll AP, Shenoi SV. “It’s about my life”: facilitators of and barriers to isoniazid preventive therapy completion among people living with HIV in rural South Africa. AIDS Care. 2017;29(7):936–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makanjuola T, Taddese HB, Booth A. Factors associated with adherence to treatment with isoniazid for the prevention of tuberculosis amongst people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review of qualitative data. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gust DA, Mosimaneotsile B, Mathebula U, Chingapane B, Gaul Z, Pals SL, et al. Risk Factors for Non-Adherence and Loss to Follow-Up in a Three-Year Clinical Trial in Botswana. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mindachew M, Deribew A, Memiah P, Biadgilign S. Perceived barriers to the implementation of Isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource constrained settings: a qualitative study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17(26):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lester R, Hamilton R, Charalambous S, Dwadwa T, Chandler C, Churchyard GJ, et al. Barriers to implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV clinics: a qualitative study. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 5):S45–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub J, Lebina L, Qomfu C, Chon S, Cohn S, Masonoke K, et al. Implementation of QuantiFERON®– TB Gold In-Tube test for diagnosing latent tuberculosis among newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients in South Africa In: In: 46th World Conference on Lung Health of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union). Cape Town, South Africa; 2015. p. Abstract OA-399–05. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerrigan D, Tudor C, Motlhaoleng K, Lebina L, Qomfu C, Variava E, et al. Relevance and acceptability of using the Quantiferon gold test (QGIT) to screen CD4 blood draws for latent TB infection among PLHIV in South Africa: formative qualitative research findings from the TEKO trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey. 2015;

- 17.Louviere J, Lings I, Islam T, Gudergan S, Flynn T. An introduction to the application of (case 1) best-worst scaling in marketing research. Int J Res Mark. 2013;30(3):292–303. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flynn TN. Valuing citizen and patient preferences in health: recent developments in three types of best-worst scaling. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marley AAJ, Louviere JJ. Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best–worst choices. J Math Psychol. 2005;49(6):464–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen EM, Segal JB, Bridges JFP. A framework for instrument development of a choice experiment: an application to type 2 diabetes. Patient. 2016;9(5):465–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheung K long Wijnen BF, Hollin IL Janssen EM, Bridges JF Evers SMAA, et al. Using Best – Worst Scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(12):1195–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown L, Lee T, De Allegri M, Rao K, Bridges JF. Applying stated-preference methods to improve health systems in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(5):441–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Zweifel P, Johnson FR. Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling : an overview. Health Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Getahun H, Granich R, Sculier D. Implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV worldwide: barriers and solutions. Aids. 2010; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufman MR, Cornish F, Zimmerman RS, Johnson BT. Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalabh HT. Statistical Analysis of Designed Experiments, Third Edition. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molassiotis A, Emsley R, Ashcroft D, Caress A, Ellis J, Wagland R, et al. Applying Best-Worst scaling methodology to establish delivery preferences of a symptom supportive care intervention in patients with lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best--worst scaling: What it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou M, Thayer WM, Bridges JFP. Using Latent Class Analysis to Model Preference Heterogeneity in Health: A Systematic Review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;36(2):175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–69. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marley AAJ, Louviere JJ. Some probabilistic models of best, worst, and best–worst choices. J Math Psychol. 2005;49(6):464–80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohn D, O’Brien R, Geiter L, Gordin F. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal. 2000;49(6):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.M’Imunya J, Kredo T, Volmink J. Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim H-Y, Dowdy DW, Martinson NA, E Golub J, Bridges JFP, Hanrahan CF. Maternal priorities for preventive therapy among HIV-positive pregnant women before and after delivery in South Africa: a best-worst scaling survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(7):e25143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omesa EN, Kathure EM, Mulwa R, Maritim A, Owiti PO, Takarinda KC, et al. Uptake of isoniazid preventive therapy and associated factors among HIV positive patients in an urban health centre, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2016;93(10):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakrapani V, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Kurian AK, Dubrow R. Barriers to free antiretroviral treatment access for female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(11):973–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.