Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine the mediating role of psychological distress on the associations between two forms of harassment, military sexual trauma (MST) and sexual orientation-based discrimination (SOBD), and alcohol use in a sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) military personnel.

Methods

Data were analyzed from 254 LGB military service members in the United States. Bivariate associations were examined between MST, SOBD, anxiety and depression, distress in response to stressful military events, and alcohol use. A latent psychological distress factor was estimated using anxiety and depression, and distress in response to stressful military events. Path analyses were used to estimate the direct effects of MST and SOBD on alcohol use and the indirect effects of MST and SOBD on alcohol use through psychological distress.

Results

All bivariate associations were positive and significant between MST, SOBD, anxiety and depression, distress in response to military events, and alcohol use. In multivariable analyses, after adjusting for demographic covariates, a significant indirect effect was observed for SOBD on alcohol use through psychological distress. MST was not directly or indirectly associated with alcohol use when SOBD was included in the path model.

Conclusion

Overall, findings suggest SOBD is associated with poorer mental health, which in turn places LGB military personnel at greater risk of alcohol use and associated problems. These results affirm the need for interventions that reduce SOBD in the military and suggest that these interventions will have a positive impact on the health of LGB military personnel.

Keywords: LGB, military, harassment, mental health, alcohol

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals have a longstanding history of serving in the United States military (Shlits, 1993; Sinclair, 2009). However, it was not until the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue – a policy that forced LGB military personnel to conceal their sexual orientation or face discharge – that LGB members could serve openly. In studies that focus on LGB military personnel, it is clear that the intersection of being both LGB and in the military presents an increased risk for harassment and mental health disorders (Matarazzo et al., 2014).

LGB civilians have demonstrated increased risk for mental health disorders, such as depression (Williamson, 2000), anxiety (S. D. Cochran & Mays, 2009), and post-traumatic stress (Roberts, Austin, Corliss, Vandermorris, & Koenen, 2010), compared to heterosexual civilians. Military personnel, both active duty service members and veterans, also experience higher rates of the same diagnoses compared to civilian populations (Hoerster et al., 2012; Magruder & Yeager, 2009), and these conditions have high levels of comorbidity among military personnel (Campbell et al., 2007; Ginzburg, Ein-Dor, & Solomon, 2010; Kozaric-Kovacic & Kocijan-Hercigonja, 2001). Based on this research, LGB military personnel are potentially more vulnerable to mental health problems due to combined stress of being LGB and serving in the military. Although research is limited, risk for post-traumatic stress and depression are significantly higher, and symptoms are more severe, among LGB veterans compared to heterosexual veterans (Hankin et al., 1999; Ray-Sannerud, Bryan, Perry, & Bryan, 2015).

Military sexual trauma (MST), defined as sexual harassment or physical sexual assault that occurred while the victim was in the military (Suris & Lind, 2008), is prevalent within the military and a significant risk factor for development of the aforementioned mental health problems (Groves, 2013). Although prevalence rates vary, most studies report rates of MST ranging from 20% - 43% (Suris & Lind, 2008). In terms of mental health, MST is commonly associated with an increased risk of post-traumatic stress with comorbid anxiety and depression (Maguen et al., 2012; Ray-Sannerud et al., 2015; Suris & Lind, 2008; Suris, Lind, Kashner, Borman, & Petty, 2004). In fact, MST has been evidenced to be one of the strongest predictors of post-traumatic stress and to have an equal or higher impact on psychological well-being than combat exposure (Kang, Dalager, Mahan, & Ishii, 2005; Kimerling, Gima, Smith, Street, & Frayne, 2007).

Sexual orientation-based discrimination (SOBD) is any enacted expression of stigma that occurs in connection to one’s sexual minority identity (National Defense Research Institute, 2010). SOBD is an interpersonal sexual minority stressor that contributes to the development of more proximal intrapersonal sexual minority stress (e.g., internalized stigma, expectations of rejection), and has been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes among LGB individuals (Gilbert & Zemore, 2016; Lee, Gamarel, Bryant, Zaller, & Operario, 2016). For example, among LGB civilians, SOBD has been evidenced to be associated with post-traumatic stress (Robinson & Rubin, 2016). Furthermore, anticipated SOBD has been evidenced to be predictive of worse trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms (Chaudoir & Quinn, 2016; Pachankis, 2007). However, less is known about these associations among LGB military personnel.

Although research documenting the prevalence of SOBD, MST, and related health outcomes within the military remains limited, some research indicates high rates of SOBD and MST for LGB military personnel. For example, nearly half (47%) of participants in an online survey of 445 LGB veterans reported experiencing at least one incident of verbal, physical, or sexual assault (American Psychological Association Joint Divisional Task Force on Sexual Orientation and Military Service, 2009). The negative health consequences of this experience for LGB military personnel is supported by research demonstrating a positive association between SOBD and lifetime and past-year Veterans Health Administration utilization among LGB veterans (Simpson, Balsam, Cochran, Lehavot, & Gold, 2013).

Exposure to stress is associated with greater rates of alcohol use among military personnel (Schumm & Chard, 2012). For LGB military personal, adaptive coping responses, sufficient for dealing with normative general stressors, may be insufficient for managing the increased burden of stress associated with experiences of harassment and associated mental health problems, resulting in the increased use of less adaptive strategies (e.g., alcohol; Kelley et al., 2013; Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, Grant, & Hasin, 2012; Marshall et al., 2012; McFarlane, 1998). Rates of heavy drinking and binge drinking among active-duty military personnel more broadly have been consistently elevated (Bray, Brown, & Williams, 2013). In fact, excessive alcohol use has been estimated to result in the loss of about 320,000 work days and 12,600 active duty military personnel being unable to deploy or being removed from service each year (Schumm & Chard, 2012). Less is known about alcohol use among LGB military personnel but some research has indicated higher rates of alcohol use disorders among LGB veterans (B. N. Cochran, Balsam, Flentje, Malte, & Simpson, 2013).

Overall, there is limited previous research on the effects of MST and SOBD on alcohol use among LGB military personnel. Research among military personnel more broadly supports a positive association between alcohol use and non-combat related trauma, including MST (Creech & Borsari, 2014; Hankin et al., 1999; Suris & Lind, 2008). Further, there is evidence to suggest that psychological distress may contribute to increased alcohol use among military personnel and veterans (Cadigan, Klanecky, & Martens, 2017; Kline et al., 2014; Schumm & Chard, 2012; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Lehavot, & Kaysen, 2014). Based on the evidence reviewed above, the purpose of this study was to examine the effects of MST and SOBD on psychological distress and alcohol use in a sample of LGB military personnel. We predicted that LGB service members who experience more MST and SOBD would present with more symptoms of psychological distress and alcohol use.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were collected as part of a study of LGB military service members in the United States. Participants were recruited on the internet via listservs, social media, and social networks of the Armed Forces between April 2012 and October 2013. Eligible participants were at least 18 years old, LGB self-identified, and active within the United States Armed Forces during the past five years or a reservist.

After completing an online survey administered on the Qualtrics platform, participants were compensated with a $10 electronic gift card and entered in a drawing for an additional $50 gift card, which was held each time 50 surveys were completed. In total, 729 surveys were started, 467 participants provided informed consent, and 321 were eligible to complete the survey. Of those that were eligible, 254 participants completed the survey. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City Univer- sity of New York.

Measures

Demographics

Participants provided information about age, sexual orientation, gender, race/ethnicity, HIV-status, education, relationship status, income, branch of military, most recent position in military, and active duty status. For sexual orientation, participants were asked to select if they identified as gay or lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual. For gender, participants were asked to select whether they currently identified as male or female.

Experiences of harassment

Sexual orientation-based discrimination

Eight survey items based on a Department of Defense (DOD) report (National Defense Research Institute, 2010) were used to assess participant’s experiences of sexual orientation-based offensive or hostile speech, gestures, intimidation, vandalism, physical assault, and workplace discrimination. Participants rated each item based on how frequently they witnessed or experienced each item involving military personnel in the previous year. Items were rated using a Likert-type type scale ranging from one (Never) to five (Very Often) and summed as an indicator of overall experience. The measure has been previously validated for use among military personnel (Estrada, Probst, Brown, & Graso, 2011) and demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (α = .90).

Military sexual trauma

MST was assessed using 19 items from a 2010 survey of active duty members that examined the frequency of experienced sexual harassment and sexual assault by military personnel, DOD service civilian employees, and/or contractors within the past year (Rock, Lipari, Cook, & Hale, 2011). The items assessed exposure to unwanted or uninvited offensive language (e.g., sexual jokes; sexist remarks; comments about appearance), sexual coercion (e.g., repeated attempts to establish romantic and/or sexual relationships; retaliatory behavior for not sexually cooperating), and sexual acts (e.g., inappropriate touching; non-consensual sex). Items were rated using a Likert-type scale ranging from zero (Never) to four (Very Often) and summed as an indicator of overall experience. This measure has been previously validated for use with military personnel (Ormerod, Nye, Joseph, Fitzgerald, & Rock, 2010) and demonstrated good internal reliability in the present study (α = .95).

Psychological distress

We used the Military Version of the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-M; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) to capture distress in response to stressful military experiences. Participants responded to 17 different statements, which described symptoms that veterans sometimes have in response to stressful military experiences, by rating how much they have been bothered by each symptom in the last month. Each item was rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from one (Not at all) to five (Extremely) and the scale demonstrated good internal reliability (α = .94). The twelve-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) was used to assess anxiety and depression symptoms in the past week (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Participants rated each item on a Likert-type scale ranging from zero (Not at all) to four (Extremely). The scale demonstrated good internal reliability (α = .93).

Alcohol use

Participants completed the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) to assess alcohol use in the previous six months (Babor & Grant, 1989). Likert-type scales assessed drinking frequency (one item; 0 = never; 4 = four or more times per week), quantity of alcohol consumption on a typical drinking day (one item; 0 = 1–2 drinks; 4 = 10 or more drinks), problems related to alcohol consumption (six items; 0 = never; 4 = daily or almost daily), physical injury to self or others as a result of drinking (one item; 0= no; 2 = yes, during the last six months), and concerns regarding their drinking shared by others (one item; 0 = no; 4 = yes, during the last six months). Items were summed to create a total scale score (α = .78).

Analysis Plan

First, we conducted bivariate analyses using SPSS (version 24). We assessed demographic differences across key variables using ANOVAs and further investigated significant group differences using Tukey-Kramer tests. Next, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients to assess bivariate associations between continuous variables. Finally, we estimated three path analysis models in stepwise fashion using Mplus (version 8.0) to test the hypothesized direct effects of MST on alcohol problems, the hypothesized direct effect of SOBD on alcohol problems, and the hypothesized indirect effects of MST and SOBD on alcohol problems through psychological distress. This approach allowed multiple regressions to be tested simultaneously along with estimates of the direct effects of our predictors (MST and SOBD) and the indirect effects through psychological distress on alcohol use. Previous research has demonstrated strong correlations and high levels of comorbidity among traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety disorders, and some of this research suggests that these different disorders load onto a single psychological distress factor (Caspi et al., 2014; Slade & Watson, 2006). In the present study, the PCL-M was assessed in response to stressful military experiences rather than a specific traumatic event and all participants completed the PCL-M regardless of trauma exposure. As such, we decided to examine a single latent factor representing psychological distress that included PCL-M scores, as well as anxiety and depression symptoms. In the first path model, MST was examined as a predictor of alcohol use with psychological distress as a mediator. In the second path model, SOBD was examined as a predictor of alcohol use with psychological distress as a mediator. In the third path model, MST and SOBD were simultaneously examined as independent predictors of alcohol use with psychological distress as a mediator. We utilized default maximum likelihood estimation and each path in our model was adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, HIV-status, relationship-status, income, and active-duty status. We evaluated model fit using standard indices including a non-significant chi-square statistic for the model, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.06, a comparative fit index (CFI) greater than 0.95, and a Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) greater than 0.95.

Results

The final analytic sample included 254 LGB military personnel. Demographic characteristics of the sample and associations between demographics and variables of interest are presented in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 73 (M=30.4, SD=7.8). Participants who identified as female reported significantly more MST compared to those who identified as male. White participants reported significantly less MST compared to those who identified as a race/ethnicity other than Black, White, or Hispanic. Bisexual participants reported significantly more MST, depression and anxiety, and higher PCL-M scores compared to those who identified as lesbian or gay. HIV-positive participants reported significantly less alcohol use compared to HIV-negative/unknown participants. Participants with a high school diploma reported significantly more MST compared to those with college degrees, and those with a GED or less reported significantly more depression and anxiety compared to those with some graduate school. Single participants reported more depression and anxiety, and alcohol use compared to those in relationships. Participants earning less than $20,000 a year reported significantly more MST, SOBD, depression and anxiety, and high PCL-M scores compared to the higher income groups. In general, participants in the Army reported the highest rates of MST, SOBD, depression, anxiety, and PCL-M scores. Participants who were enlisted reported significantly higher PCL-M scores compared to officers. Participants who reported active duty status endorsed significantly less MST, depression and anxiety, and PCL-M scores compared to those who were inactive. As shown in Table 2, there were significant positive correlations between MST, SOBD, depression and anxiety symptoms, PCL-M scores, and alcohol use.

Table 1.

Comparisons of harassment, psychological distress, and alcohol use by demographic characteristics.

| Full Sample (N=254) |

Sexual Orientation Based Discrimination |

Military Sexual Trauma |

Depression & Anxiety Symptoms |

PCL-M Scores |

Alcohol Use |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | M | F (p) | M | F (p) | M | F (p) | M | F (p) | M | F (p) | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 86 | 33.9 | 11.85 | 0.00 (.983) | 11.51 | 6.65 (.011) | 1.47 | 2.13 (.146) | 26.05 | 0.10 (.748) | 5.45 | 0.80 (.373) |

| Male | 168 | 66.1 | 11.83 | 7.33 | 1.61 | 26.55 | 6.01 | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Black | 13 | 5.1 | 10.62 | 0.98 (.404) | 9.62a,b | 5.21 (.002) | 1.51 | 2.62 (.051) | 23.31 | 1.47 (.224) | 2.92 | 2.58 (.054) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 38 | 15.0 | 10.87 | 9.08a,b | 1.72 | 27.55 | 6.68 | |||||

| White | 172 | 67.7 | 11.95 | 7.22a | 1.48 | 25.73 | 5.68 | |||||

| Other | 31 | 12.2 | 12.90 | 16.48b | 1.80 | 29.84 | 6.77 | |||||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||||||

| Gay or Lesbian | 222 | 87.4 | 11.90 | 0.22 (.642) | 8.15 | 4.13 (.043) | 1.52 | 6.49 (.011) | 25.64 | 7.05 (.008) | 5.63 | 3.08 (.080) |

| Bisexual | 32 | 12.6 | 11.41 | 12.88 | 1.85 | 31.53 | 7.19 | |||||

| HIV Status | ||||||||||||

| Negative/Unknown | 240 | 94.5 | 11.94 | 1.47 (.227) | 9.00 | 1.76 (.168) | 1.56 | 0.00 (.999) | 26.35 | 0.02 (.878) | 5.98 | 4.59 (.033) |

| Positive | 14 | 5.5 | 10.07 | 4.50 | 1.56 | 26.86 | 3.21 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| GED or less | 11 | 4.3 | 12.82 | 2.21 (.087) | 9.64a,b | 5.00 (.002) | 2.12a | 3.51 (.016) | 33.18a | 3.66 (.013) | 7.55 | 2.63 (.051) |

| HS Diploma | 129 | 50.8 | 12.57 | 11.52a | 1.59a,b | 27.94a | 5.69 | |||||

| BA | 63 | 24.8 | 11.40 | 5.70b | 1.54a,b | 24.27a | 6.79 | |||||

| Graduate School | 51 | 20.1 | 10.33 | 5.31b | 1.39b | 23.59a | 4.59 | |||||

| Relationship Status | ||||||||||||

| Single | 106 | 41.7 | 11.93 | 0.51 (.819) | 9.45 | 0.59 (.443) | 1.72 | 9.13 (.003) | 27.20 | 0.86 (.355) | 7.16 | 15.45 (.000) |

| Partnered | 148 | 58.3 | 11.77 | 8.24 | 1.45 | 25.80 | 4.86 | |||||

| Income | ||||||||||||

| Less than $19,999 | 39 | 15.4 | 15.54a | 12.05 (.000) | 14.90a | 8.87 (.000) | 1.86a | 4.42 (.013) | 31.51a | 4.42 (.013) | 5.90 | 1.18 (.311) |

| $20,000 to $74,999 | 166 | 65.4 | 11.48b | 8.69b | 1.51b | 25.42b | 5.54 | |||||

| $75,000 or more | 49 | 19.3 | 10.12b | 4.06b | 1.47b | 25.57b | 6.71 | |||||

| Branch of Military | ||||||||||||

| Army | 86 | 33.9 | 13.65a | 4.52 (.002) | 13.08a | 4.47 (.002) | 1.73a | 2.48 (.045) | 29.92a | 3.41 (.010) | 5.56 | 0.77 (.547) |

| Navy | 56 | 22.0 | 11.98a,b | 7.36b | 1.53a,b | 25.61a,b | 5.89 | |||||

| Marine Corps | 21 | 8.3 | 9.76b | 6.86a,b | 1.44a,b | 24.43a,b | 6.57 | |||||

| Air Force | 74 | 29.1 | 10.38b | 6.36b | 1.40b | 23.39b | 5.50 | |||||

| Coast Guard | 17 | 6.7 | 11.12a,b | 4.06b | 1.63a,b | 26.47a,b | 7.41 | |||||

| Most Recent Position | ||||||||||||

| Enlisted | 137 | 53.9 | 12.36 | 1.71 (.165) | 10.01a | 2.69 (.047) | 1.66 | 2.19 (.090) | 28.04a | 3.03 (.030) | 5.67 | 0.88 (.452) |

| Officer | 77 | 30.3 | 10.82 | 6.58a | 1.40 | 23.12b | 6.48 | |||||

| Reservist | 21 | 8.3 | 11.05 | 4.81a | 1.54 | 26.05a,b | 5.10 | |||||

| National Guard | 19 | 7.5 | 13.11 | 12.74a | 1.54 | 28.00a,b | 5.05 | |||||

| Active Duty | ||||||||||||

| No | 75 | 29.5 | 13.13 | 5.75 (.017) | 9.88 | 0.89 (.346) | 1.73 | 6.15 (.014) | 30.35 | 12.40 (.001) | 5.67 | 0.12 (.734) |

| Yes | 179 | 70.5 | 11.30 | 8.27 | 1.49 | 24.72 | 5.89 | |||||

Note: Rows within the same column that have different superscripts differed significantly in post hoc analyses at p < 0.05 using Tukey-Kramer tests.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients among key variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| 2. Military Sexual Trauma | −.21*** | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| 3. Sexual Orientation-Based Discrimination | −.09 | .68*** | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| 4. Anxiety & Depression Symptoms | −.06 | .34*** | .39*** | ─ | ─ | ─ |

| 5. PCL-M Scores | .02 | .38*** | .44*** | .75*** | ─ | ─ |

| 6. Alcohol Use | −.14* | .19** | .17** | .26*** | .28*** | ─ |

| Mean | 30.14 | 8.75 | 11.84 | 1.56 | 26.38 | 5.82 |

| Standard Deviation | 7.78 | 12.36 | 5.62 | 0.71 | 11.88 | 4.72 |

| Cronbach’s α | ─ | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.78 |

Note:

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

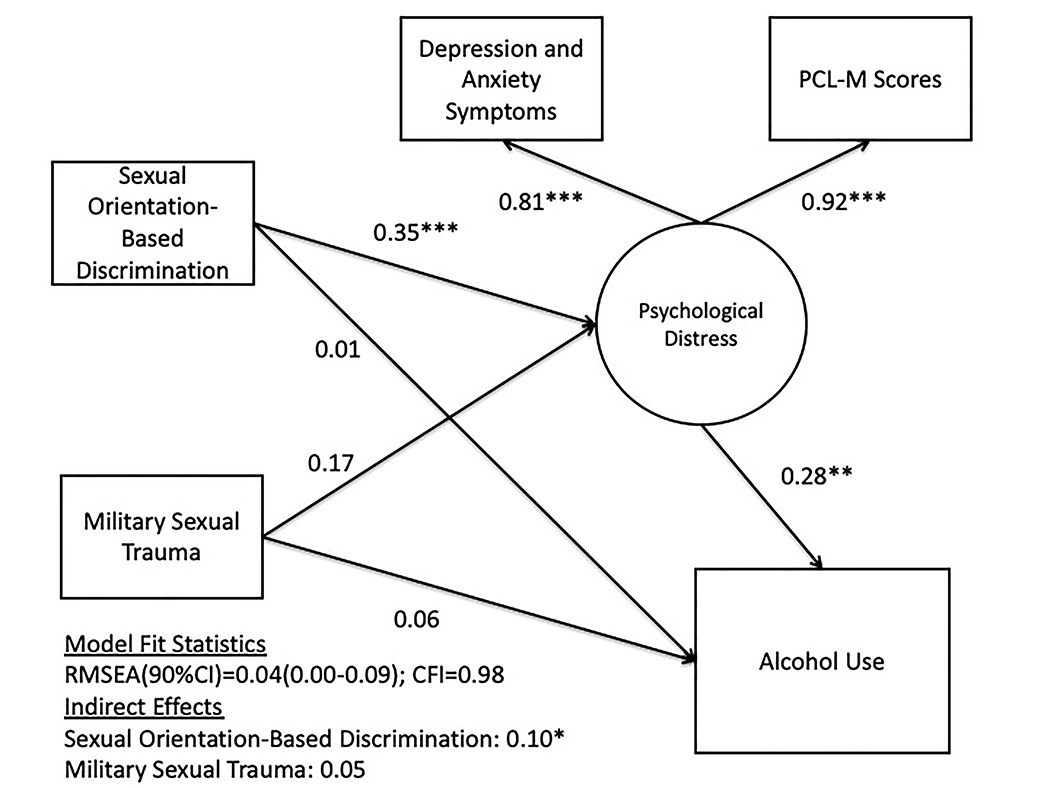

Path coefficients and model fit statistics are presented in detail in Table 3. All models were adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, HIV-status, relationships status, income, and active-duty status. In the first model, MST was significantly associated with greater psychological distress and psychological distress was significantly associated with greater alcohol use. A significant positive indirect effect was observed for MST on alcohol use through psychological distress. The model demonstrated good fit and accounted for 26.2% of the variance in psychological distress and 17.0% of the variance in alcohol use. In the second model, SOBD was significantly associated with greater psychological distress and psychological distress was significantly associated with greater alcohol use. A significant positive indirect effect was observed for SOBD on alcohol problems through psychological distress. The model demonstrated good fit and accounted for 30.6% of the variance in psychological distress and 16.8% of the variance in alcohol use. Finally, in the third model that included MST and SOBD as predictors of alcohol use along with psychological distress as a mediator, SOBD was significantly associated with greater psychological distress and psychological distress was significantly associated with greater alcohol use. MST was not significantly associated with psychological distress or alcohol use when MST and SOBD were included in the same model. A significant positive indirect effect was observed for SOBD on alcohol use through psychological distress. Model fit improved slightly in the third model compared to the first and second models that examined SOBD and MST independently. The third model is presented in Figure 1. Overall, the third model accounted for 32.0% of the variance in psychological distress and 17.0% of the variance in alcohol use.

Table 3.

Predictors of Alcohol Use among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults in the Military

| Alcohol Use Step 1 |

Alcohol Use Step 2 |

Alcohol Use Step 3 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized |

Standardized |

Unstandardized |

Standardized |

Unstandardized |

Standardized |

|||||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Measurement Model | ||||||||||||

| Psychological Distress Factor | ||||||||||||

| Depression and Anxiety Symptoms | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.82 | 0.05 *** | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.05 *** | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.05 *** |

| PCL-M Scores | 18.78 | 2.50 | 0.91 | 0.06 *** | 18.97 | 2.31 | 0.92 | 0.05 *** | 18.94 | 2.24 | 0.92 | 0.05 *** |

| Structural Model | ||||||||||||

| MST →Psychological Distress | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.11 *** | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| SOBD →Psychological Distress | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.09 *** | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.11 *** |

| MST →Alcohol Use | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| SOBD →Alcohol Use | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Psychological Distress →Alcohol Use | 2.28 | 0.76 | 0.28 | 0.08 *** | 2.33 | 0.81 | 0.28 | 0.09 ** | 2.28 | 0.81 | 0.28 | 0.09 ** |

| Indirect Effect | ||||||||||||

| MST →Psychological Distress →Alcohol Use | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.05 * | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| SOBD →Psychological Distress →Alcohol Use | ─ | ─ | ─ | ─ | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.51 * | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.04 * |

| Model Fit | ||||||||||||

| χ2 | 12.25 (8) p=.140 | 12.04 (8) p=.150 | 11.83 (9) p=.223 | |||||||||

| CFI | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.99 | |||||||||

| TLI | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | |||||||||

| RMSEA | 0.05 90%CI (0.00–0.09) | 0.05 90%CI (0.00–0.09) | 0.04 90%CI (0.00–0.08) | |||||||||

Note: MST = military sexual trauma. SOBD = sexual orientation-based discrimination. Model adjusted for age, gender, sexual orientation, HIV-status, relationship-status, income, and active-duty status.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

Figure 1.

Path model depicting the direct and indirect associations between MST, SOBD, psychological distress, and alcohol use. All beta coefficients displayed are standardized model effects.

Discussion

SOBD and MST were associated with greater psychological distress and greater alcohol use among LGB military personnel. Significant indirect effects were observed for MST and SOBD when examined independently as predictors of alcohol use through symptoms of psychological distress. However, in the final model of our analyses – which included both MST and SOBD as predictors of alcohol use – a significant indirect effect was observed for SOBD on alcohol use through psychological distress and the indirect effect of MST on alcohol use through psychological distress was no longer significant. Conceptually, this suggests that individuals who reported experiences of MST were also likely to report experienced SOBD and any effect of MST on alcohol use is likely shared by SOBD. Overall, the findings from this study suggest that SOBD may be a driving factor for alcohol use among LGB military personnel due to the associated elevations in psychological distress.

Our findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating associations between SOBD and greater risk of psychological distress and substance use among LGB individuals (Dermody et al., 2014; Nadal, Whitman, Davis, Erazo, & Davidoff, 2016; Wilder & Wilder, 2012). In fact, LGB individuals experience a range of unique and chronic stressors based on stigmatizing attitudes rooted in heterosexism, and this stigma adversely affects the health of these individuals (Meyer, 2003). Among LGB veterans, elevated rates of psychological distress and alcohol use have been observed compared to heterosexual veterans (B. N. Cochran et al., 2013). Our findings extend this previous research and suggest that SOBD is associated with increased risk of psychological distress among LGB military personnel. As a consequence, LGB military personnel who experience SOBD may also be at increased risk of problematic alcohol use due to effects of psychological distress.

In contrast to our expectations, MST was not associated with psychological distress or alcohol use when SOBD and MST were examined in the same model. Previous research involving military personnel more broadly has demonstrated an association between MST and alcohol problems through elevations in post-traumatic stress (Hahn, Tirabassi, Simons, & Simons, 2015). One possibility for our unexpected finding is that there is significant overlap between experiences of SOBD and MST, which was supported by the strong correlation between these measures in the present study. Similar to sexual violence, SOBD can serve as attempts to assert heterosexuality and establish dominance over LGB individuals (Groves, 2013). Indeed, masculinity and dominance are traits that are highly valued in heterosexist societies, including the military (Turchik & Wilson, 2010). Research from the general population indicates that LGB individuals experience greater rates of sexual victimization across the lifespan compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Walters, Chen, & Breiding, 2013). Taken together, our findings do not dispute previous research that demonstrates the adverse impact of sexual victimization on mental health among military personnel. Rather, they suggest that when MST and SOBD are considered together, SOBD remains a dominant risk factor for psychological distress and associated alcohol use among LGB military personnel.

Although our analyses are based on cross-sectional data, they are consistent with previous ecological momentary assessment research, involving sexual and gender minorities, that has demonstrated increased psychological distress and increased rates of alcohol use following experiences of SOBD (Livingston et al., 2020; Livingston, Flentje, Heck, Szalda-Petree, & Cochran, 2017). Further, they are consistent with research that suggests alcohol use may increase as psychological distress increases due to reinforcing immediate, but short-term, relief alcohol provides for these symptoms (Bandermann & Szymanski, 2014; Kelley et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2012; McFarlane, 1998; Schumm & Chard, 2012). Overall, our study, in combination with this previous research, suggests that SOBD has significant consequences in terms of alcohol use among LGB military personnel and efforts to reduce SOBD in the military would have positive implications for alcohol use in this population.

Our study highlights the need to prevent experiences of SOBD in the military as these experiences may contribute to the greater rates of psychological distress and substance use observed among LGB military personnel (B. N. Cochran et al., 2013). As mentioned, heterosexist values are associated with SOBD in the military, but SOBD also negatively is also associated with poorer social cohesion, something that is also highly valued in the military (Goldbach & Castro, 2016). As such, efforts to reduce SOBD may also benefit the military more broadly by improving cohesion among service members. Previous reviews have highlighted a range of structural and interpersonal interventions for reducing rates of SOBD (Chaudoir, Wang, & Pachankis, 2017; Hatzenbuehler, 2016). These reviews suggest that the development and enforcement of non-discrimination policies, training leadership to recognize and stop SOBD, and including LGB individuals in leadership roles may help create social spaces that are more affirming of LGB identities. In the military, removal of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue policy was an important first step toward a less exclusive environment for LGB military personnel and the aforementioned interventions are needed to create an integrated and inclusive environment for LGB military personnel. Furthermore, other researchers have argued that preventing SOBD may also result in reductions of MST as both of these acts are rooted in similar heterosexist attitudes (Burks, 2011).

Limitations

The present study should be considered in light of some limitations. First, as mentioned, the data used is this study are cross-sectional and provide limited information as to the direction of the observed associations. Although we have highlighted previous research that has demonstrated greater rates of psychological distress and alcohol use as a direct consequence of SOBD, the implications of the present study would be strengthened by additional longitudinal research that includes more robust assessments of psychological distress and alcohol use (e.g., EMA). Second, although our measures of MST and SOBD have been previously validated independently for use in samples of military personnel, these measures shared a strong correlation in the present study and multicollinearity between the two measures may have obscured the effects of MST on psychological distress and alcohol use. Our measurement of SOBD did not include items related to sexual assault but the MST measure did include some items that were related to gender-based discrimination, which could overlap with some of the SOBD items. Third, our sample was limited in demographic variation and a more diverse sample would have allowed for a more nuanced investigation of demographic differences. For example, previous research has demonstrated greater rates of victimization, psychological distress, and substance use among those who identify as bisexual and those who are HIV-positive. Considering these limitations, the findings from the present study would be further supported by future research that examined the impacts of MST and SOBD on psychological distress and alcohol use in a diverse sample of LGB military personnel and incorporated a longitudinal repeated-measures design.

Conclusion

LGB military personnel experience significant levels of harassment and discrimination in the military. The results from the present study are consistent with previous research that suggests SOBD is associated with elevations in psychological distress, and as a consequence greater rates of alcohol use. Together, our findings suggest that preventing SOBD in the military would be associated with improvements in mental health and reductions in alcohol use among military personnel. As such, interventions are needed that promote more inclusive policies protecting LGB military personnel from discrimination, train military personnel to recognize and stop SOBD, and integrate more LGB military personnel into leadership positions. These efforts are likely to that contribute to an environment that is more affirming of LGB military personnel and result in improved health outcomes in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire team of CHEST staff, interns, volunteers, and recruiters, with special thanks to Christian Grov, PhD and John Pachankis, PhD, Matthew Wachman, Aaron Belkin, PhD, Andrew Jenkins, Grace Macalino, PhD, Admiral Steinman, Katie Miller, Ron Nalley, Jeff Meuller, Maj USAF, OutServe-SLDN, and our participants who volunteered their time. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided through collaboration between the Palm Center and the Center for HIV Educational Studies and Training (CHEST) at Hunter College, City University of New York (CUNY).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RM, upon reasonable request.

References

- American Psychological Association Joint Divisional Task Force on Sexual Orientation and Military Service. (2009). Report of the Joint Divisional Task Force on Sexual Orientation and Military Service. Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbc/publications/militaryhomepage.html [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, & Grant M (1989). From clinical research to secondary prevention: International collaboration in the development of the Alcohol Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Health & Research World, 13(4), 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- Bandermann KM, & Szymanski DM (2014). Exploring coping mediators between heterosexist oppression and posttraumatic stress symptoms among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(3), 213–224. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM, & Williams J (2013). Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the US military. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(10), 799–810. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burks DJ (2011). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual victimization in the military: An unintended consequence of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”? American Psychologist, 66(7), 604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan JM, Klanecky AK, & Martens MP (2017). An examination of alcohol risk profiles and co-occurring mental health symptoms among OEF/OIF veterans. Addictive Behaviors, 70, 54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, Yano EM, Kirchner JE, Chan D, … Chaney EF (2007). Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: Implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(6), 711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, … Poulton R (2014). The p factor: one general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 119–137 %@ 2167–7026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, & Quinn DM (2016). Evidence that anticipated stigma predicts poorer depressive symptom trajectories among emerging adults living with concealable stigmatized identities. Self and Identity, 15(2), 139–151. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1091378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Balsam K, Flentje A, Malte CA, & Simpson T (2013). Mental health characteristics of sexual minority veterans. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(2–3), 419–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, & Mays VM (2009). Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 647–658. doi: 10.1037/a0016501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech SK, & Borsari B (2014). Alcohol use, military sexual trauma, expectancies, and coping skills in women veterans presenting to primary care. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2), 379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Marshal MP, Cheong J, Burton C, Hughes T, Aranda F, & Friedman MS (2014). Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(1), 30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory - An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. doi:Doi 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada AX, Probst TM, Brown J, & Graso M (2011). Evaluating the Psychometric and Measurement Characteristics of a Measure of Sexual Orientation Harassment. Military Psychology, 23(2), 220–236. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.559394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, & Zemore SE (2016). Discrimination and drinking: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine, 161, 178–194. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg K, Ein-Dor T, & Solomon Z (2010). Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression: A 20-year longitudinal study of war veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 123(1–3), 249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, & Castro CA (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) service members: life after don’t ask, don’t tell. Current psychiatry reports, 18(6), 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves C (2013). Military sexual assault: An ongoing and prevalent problem. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(6), 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AM, Tirabassi CK, Simons RM, & Simons JS (2015). Military sexual trauma, combat exposure, and negative urgency as independent predictors of PTSD and subsequent alcohol problems among OEF/OIF veterans. Psychological Services, 12(4), 378–383. doi: 10.1037/ser0000060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin CS, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, Miller DR, Frayne S, & Tripp TJ (1999). Prevalence of depressive and alcohol abuse symptoms among women VA outpatients who report experiencing sexual assault while in the military. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12(4), 601–612. doi:Doi 10.1023/A:1024760900213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerster KD, Lehavot K, Simpson T, McFall M, Reiber G, & Nelson KM (2012). Health and health behavior differences US military, veteran, and civilian men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(5), 483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Dalager N, Mahan C, & Ishii E (2005). The role of sexual assault on the risk of PTSD among Gulf War veterans. Annals of Epidemiology, 15(3), 191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Runnals J, Pearson MR, Miller M, Fairbank JA, Brancu M, … Registry VM-AM (2013). Alcohol use and trauma exposure among male and female veterans before, during, and after military service. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 133(2), 615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, Street A, & Frayne S (2007). The Veterans Health Administration and military sexual trauma. American Journal of Public Health, 97(12), 2160–2166. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2006.092999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline A, Weiner MD, Ciccone DS, Interian A, St Hill L, & Losonczy M (2014). Increased risk of alcohol dependency in a cohort of National Guard troops with PTSD: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 50, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaric-Kovacic D, & Kocijan-Hercigonja D (2001). Assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbidity. Military Medicine, 166(8), 677–680. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000181419300002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Gamarel KE, Bryant KJ, Zaller ND, & Operario D (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. Lgbt Health, 3(4), 258–265. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston NA, Flentje A, Brennan J, Mereish EH, Reed O, & Cochran BN (2020). Real-time associations between discrimination and anxious and depressed mood among sexual and gender minorities: The moderating effects of lifetime victimization and identity concealment. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston NA, Flentje A, Heck NC, Szalda-Petree A, & Cochran BN (2017). Ecological Momentary Assessment of Daily Discrimination Experiences and Nicotine, Alcohol, and Drug Use Among Sexual and Gender Minority Individual. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(12), 1131–1143. doi: 10.1037/CCP0000252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magruder KM, & Yeager DE (2009). The prevalence of PTSD across war eras and the effect of deployment on PTSD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatric Annals, 39(8), 778–788. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20090728-04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Cohen B, Ren L, Bosch J, Kimerling R, & Seal K (2012). Gender differences in military sexual trauma and mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Womens Health Issues, 22(1), E61–E66. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Prescott MR, Liberzon I, Tamburrino MB, Calabrese JR, & Galea S (2012). Coincident posttraumatic stress disorder and depression predict alcohol abuse during and after deployment among Army National Guard soldiers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(3), 193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo BB, Barnes SM, Pease JL, Russell LM, Hanson JE, Soberay KA, & Gutierrez PM (2014). Suicide risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender military personnel and veterans: What does the literature tell us? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(2), 200–217. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC (1998). Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addictive Behaviors, 23(6), 813–825. doi:Doi 10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, & Davidoff KC (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 488–508. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Defense Research Institute. (2010). Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: An Update of RAND’s 1993 Study Retrieved from Santa Monica, CA: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2010/RAND_MG1056.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ormerod AJ, Nye CD, Joseph DL, Fitzgerald LF, & Rock LM (2010). 2010 gender relations survey of active duty members: Report on scales and measures (Report No. 2010–028). Retrieved from Arlington, VA: [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Sannerud BN, Bryan CJ, Perry NS, & Bryan AO (2015). High levels of emotional distress, trauma exposure, and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among military personnel and veterans with a history of same sex behavior. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(2), 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, & Koenen KC (2010). Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2433–2441. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2009.168971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JL, & Rubin LJ (2016). Homonegative microaggressions and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(1), 57–69. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2015.1066729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rock LM, Lipari RN, Cook PJ, & Hale AD (2011). 2010 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members: Overview Report on Sexual Harassment. Retrieved from https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a541045.pdf.

- Schumm JA, & Chard KM (2012). Alcohol and stress in the military. Alcohol Research-Current Reviews, 34(4), 401–407. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000313234200004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlits R (1993). Conduct Unbecoming: Lesbians and Gays in the U.S. military, Vietnam to the Persian Gulf. New York: Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Balsam KF, Cochran BN, Lehavot K, & Gold SD (2013). Veterans Administration health care utilization among sexual minority veterans. Psychological Services, 10(2), 223–232. doi: 10.1037/a0031281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Lehavot K, & Kaysen DL (2014). Drinking motives moderate daily relationships between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 237–247. doi: 10.1037/a0035193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair GD (2009). Homosexuality and the military: A review of the literature. J Homosex, 56(6), 701–718. doi: 10.1080/00918360903054137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade TIM, & Watson D (2006). The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychological Medicine, 36(11), 1593–1600 %@ 1469–8978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris A, & Lind L (2008). Military sexual trauma - A review of prevalence and associated health consequences in veterans. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 9(4), 250–269. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris A, Lind L, Kashner TM, Borman PD, & Petty F (2004). Sexual assault in women veterans: An examination of PTSD risk, health care utilization, and cost of care. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(5), 749–756. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138117.58559.7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchik JA, & Wilson SM (2010). Sexual assault in the US military: A review of the literature and recommendations for the future. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(4), 267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ML, Chen J, & Breiding MJ (2013). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Findings on Victimization by Sexual Orientation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder H, & Wilder J (2012). In the wake of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell: Suicide prevention and outreach for LGB service members. Military Psychology, 24(6), 624–642. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2012.737725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson IR (2000). Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Education Research, 15(1), 97–107. doi:DOI 10.1093/her/15.1.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]