Abstract

The main discussion above of the novel pathogenic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has focused substantially on the immediate risks and impact on the respiratory system; however, the effects induced to the central nervous system are currently unknown. Some authors have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 infection can dramatically affect brain function and exacerbate neurodegenerative diseases in patients, but the mechanisms have not been entirely described. In this review, we gather information from past and actual studies on coronaviruses that informed neurological dysfunction and brain damage. Then, we analyzed and described the possible mechanisms causative of brain injury after SARS-CoV-2 infection. We proposed that potential routes of SARS-CoV-2 neuro-invasion are determinant factors in the process. We considered that the hematogenous route of infection can directly affect the brain microvascular endothelium cells that integrate the blood-brain barrier and be fundamental in initiation of brain damage. Additionally, activation of the inflammatory response against the infection represents a critical step on injury induction of the brain tissue. Consequently, the virus’ ability to infect brain cells and induce the inflammatory response can promote or increase the risk to acquire central nervous system diseases. Here, we contribute to the understanding of the neurological conditions found in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection and its association with the blood-brain barrier integrity.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Blood-brain barrier, Neurological complications, Inflammatory response, Neurotropism

Coronaviruses

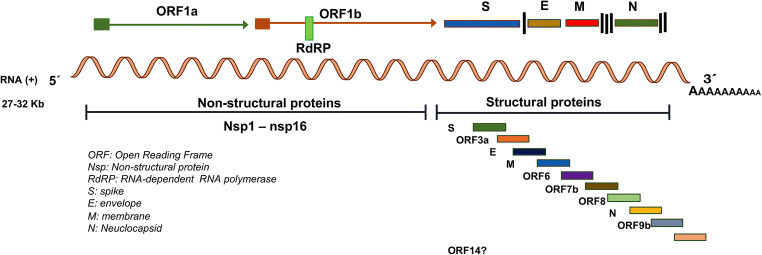

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to the order Nidovirales and family Coronaviridae which is grouped on four genera based on phylogeny: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus, and Deltacoronavirus (International Committee for Taxonomy of Virus; https://talk.ictvonline.org/). CoVs are envelopment and spherical particles of 80 to 120 nm in diameter with a crown-like structures. This family contains the largest and non-segmented RNA genome, which is formed with a single-strand positive-sense around 27 to 32 kb in size [1]. CoVs’ genome shares structural organization, although differs in the base pairs number and sequence, even among closely related CoVs. The open reading frames 1a/b (ORF1a and ORF1b), located at the 5′ end encode non-structural components, the polyproteins pp1a and pp1b. Two viral proteases cleave these proteins to generate 16 non-structural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16), including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), an important protein involved in genome transcription and replication. The 3′ end includes ORFs that encode four major structural proteins: the spike surface glycoprotein (S), a small envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleocapsid protein (N) that covers the RNA (Fig. 1). Besides, the CoV genome maintains genes that encode accessory proteins indispensable for adaptation and virulence and be successful to specific host [2, 3].

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV-2 genome organization. The SARS-CoV-2 genome size is around 32 kb and is an RNA single-strand positive-sense that encodes 16 non-structural proteins (5′ end) and 4 structural proteins (3′ end) (S, E, M, and N) and 6 accessory proteins. SARS-CoV-2 genome. The genome contains a PoliA tail at 3′ end

The Betacoronavirus are zoonotic pathogens that have a wild animal origin, for example, bat or rodent origin. This group includes pathogenic human CoVs (HCoVs), such as HCoV-229E, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-HKU1, that infect mammals and provoke mild related respiratory illness in infants, young children, elderly individuals, and immunocompetent hosts [1, 3]. However, the severe acute respiratory syndrome-related CoV (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome-related CoV (MERS-CoV) cause a severe respiratory syndrome in humans that aroused large-scale pandemics during 2002–2003 and 2012, respectively [4, 5]. Importantly, late in December 2019, Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, China, reported a cluster of cases of atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, associated with a virus that rapidly spread all over the world.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoV-2 (SARS-CoV-2)

Briefly, on December 26, 2019, a male patient of 41 years old, who worked at the local seafood market, was hospitalized in the Central Hospital of Wuhan. The patient-reported symptoms are fever, chest tightness, cough, pain, weakness, sputum production, and dyspnea [6]. For its origin, it was speculated that the disease could be associated with a CoV. This information was confirmed after the unknown virus was isolated from bronchial-alveolar lavage fluid from the patient [6]. On January 12, 2020, China publicly shared the genetic sequence of a new CoV.

Metagenomic RNA sequencing identified a new RNA virus whose genome sequence of 29,903 nucleotides was designated as WH-Human1 coronavirus [6], later referred to as 2019 novel coronavirus, and at present named as SARS CoV type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the World Health Organization (WHO). SARS-CoV-2 has an overall genome sequence identity of 82% with SARS-CoV [7] and 96.2% with batCoV RaTG13 (Rhinolophus affinis) from Yunnan province, suggesting a bat origin [8]. Although the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is zoonotic, there is no certainty of its intermediate animal host. Some studies indicated that snakes were the intermediate hosts, but the most recent research concluded that some pangolin species are the missing link [9–11].

On January 30, 2020, the WHO declared SARS-CoV-2 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and pandemic on March 11, 2020. The global situation by SARS-CoV-2 infections reported to the WHO by August 15, 2020, includes 21,026,758 confirmed cases and 755,786 deaths, while the America region reported 11,271,215 confirmed cases (https://covid19.who.int/).

Clinical Features of CoV Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Pathogenicity and transmission capacity of any pathogen are indicated from the R0 value. Epidemiologically, R0 is defined as the average number of people who will acquire a disease from an infected person. Therefore, R0 indicates the potential spread (contagious) or decline of disease. When Ro < 1, the condition will decline and eventually disappear; if R0 = 1, the disease will stay alive, but will not turn in to an epidemic; with values of Ro > 1, cases could grow exponentially and cause an epidemic or a pandemic [12]. The transmissibility and mortality rate of SARS-CoV-2 have been reported by several authors, and the estimated value is so far under debate (for more detail, see reference Liu et al. [12]). However, according to Chen et al. [13], it is estimated that SARS-CoV-2 has relatively low pathogenicity (3%) and moderate transmissibility (R0 = 1.4–5.5).

COVID-19 is the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. SARS-CoV-2 infects the higher upper respiratory tract, but with increased disease severity, the lower respiratory tract is also affected. The main routes of transmission are respiratory droplets and human-to-human, close contact [7, 14, 15]. However, oral-fecal transmission, tears secretion, aerosols, fomites, and even air and surface environmental (e.g., patient’s room, floor, air outlet fan, toilet area, and personal protective equipment) are other possible routes of virus’ transmission; nevertheless, the effectiveness of these alternative routes is still controversial [15–18]. SARS-CoV-2 infection is possible for the entire population; however, the severity of the illness depends on some highlighted aspects seen around the world. In this sense, higher percentages of infection have been diagnosed in men than in women [19–21], and elderly males (≥ 80 years) are the group more susceptible to complications [22]. Besides, chronic underlying diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cancer, have a meaningful impact in case fatality risk [22, 23]. On the other hand, pediatric patients (2 months to 17 years) may have mild symptoms or be asymptomatic; in fact, they have their own clinical features [24–27].

The period of incubation of the SARS-CoV-2, which determines the time in which symptoms are observed, has a wide range from 1 to 14 days [14, 20, 28]. Early and common symptoms by COVID-19 include fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain; other symptoms include myalgia, fatigue, and headache. Less common symptoms are sputum production, hemoptysis, and gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [22, 28–31]. Depending on illness evolution, COVID-19 might be classified according to the severity of the clinical symptoms in mild (i.e., non-pneumonia and development mild pneumonia); severe (i.e., dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥ 30 breaths per minute, blood oxygen saturation ≤ 93%, the partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio < 300, and lung infiltrates > 50% in the first 24 to 48 h); and critical (i.e., respiratory failure, sepsis, septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure, for example, heat failure, coagulopathy, acute cardiac, and acute kidney injury) [22, 23, 31].

Clinical diagnosis is made based on symptoms, exposure, and chest imaging that show the presence of lung imaging features consistent with CoVs pneumonia that includes ground-glass lung [32, 33]. The respiratory tract is the classical target for SARS-CoV-2 infection; nonetheless, the virus is also visualized by immunofluorescent staining in gastric, duodenal, and rectum glandular epithelial cells [18], showing other target tissues and complexity of the illness. Interestingly, there is evidence of signs and symptoms of COVID-19 patients (Table 1) and other HCoVs infections [38].

Table 1.

Signs of neurological associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Type of study | Signs and symptoms/cases (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

|

Retrospective, single-center case series n = 138 patients |

Dizziness 13 (9.4%) Headache 9 (6.5%) |

[21] |

|

Retrospective n = 38 patients |

Headache 3 (8%) |

[30] |

|

Retrospective, single-center study n = 99 patients |

Confusion 9 (9%) Headache 8 (8%) |

[19] |

|

Retrospective, observational case series n = 214 patients |

Neurological manifestations 78 (36.4%) Central nervous system (CNS) manifestations 53 (24.8%) Dizziness 36 (16.8%) Headache 28 (13.1%) Others symptoms: impaired consciousness, acute cerebrovascular disease, ataxia, seizure Peripheral nervous system (PNS) manifestations 19 (8.9%) Taste impairment 12 (5.6%) Smell impairment 11 (5.1%) Others symptoms: vision impairment, nerve pain |

[34] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient |

Anosmia | [35] |

|

Retrospective observational study n = 114 patient |

Anosmia associated with dysgeusia 54 (47%) |

[36] |

|

Retrospective report n = 24 males n = 19 females |

CNS syndromes Encephalopathies 10 (23%) Symptoms: confusion and disorientation, psychosis, and seizures Neuroinflammatory syndromes 12 (27%) Symptoms: encephalitis, features of an autoimmune encephalitis stimulus sensitive myoclonus, and convergence spasm. Confusion and seizure. Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM): 9 (21%) Hemorrhagic 5 (12%) Necrotizing encephalitis 1(2%), Myelitis 2(5%) Hemorrhagic leucoencephalitis 1(2%) |

[37] |

Neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2

Up to date, many reports have described the association between respiratory viral infections with neurological symptoms. There are several recognized respiratory pathogens that gain access to the central nervous system (CNS), for instance, respiratory syncytial virus, the influenza virus, the human metapneumovirus, and HCoVs (HCoV229E, HCoV-OC43, and SARS-CoV) [39], that induce manifestations such as febrile or afebrile seizures, among other encephalopathies [40, 41].

Primary cultures of human astrocytes and microglia and various human neuronal cell lines, such as the neuroblastoma SK-N-SH, the neuroglioma H4, and the oligodendrocytic MO3.13, have potential tropism for HCoV-OC43 [42]. Using an experimental animal model, HCoV-OC-43 infection also showed neuro-invasiveness and neuro-virulence [43]. Therefore, it is not surprising to find brain SARS-positive autopsies. Using in situ hybridization, the SARS genomic sequence has been detected in the cytoplasm of neurons of the hypothalamus and cerebral cortex [44]. Furthermore, Moriguchi et al. [45] confirmed the presence of the new SARS-CoV-2 in cerebral spinal fluid. In accord, epidemiological and clinical research have described neurological, non-common symptoms, and neurological manifestations associated with the SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 2). These clinical features include neuralgia, confusion, hyposmia, hypogeusia, and altered consciousness, symptoms that evidence the neurotropic invasion by SARS-CoV-2 [19, 41].

Table 2.

Neurological manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Type of study and data of patients | Neurological diagnostic, symptoms, and clinical specimen for SARS-CoV-2 detection | Reference |

|---|---|---|

|

Case series n = 4 patients 73 Y/A male, 83 Y/A female, 80 Y/A female, and 88 Y/A female |

Acute stroke Altered mental status, facial droop, slurred speech, left-side weakness, hemiplegia, and aphasia Not specific specimen |

[46] |

|

Case report n = 2 patients 31 Y/A male, 62 Y/A female |

Hunt and Hess grade 3 subarachnoid hemorrhage from a rupture aneurysm Headache and loss of consciousness Ischemic stroke Nasal specimen |

[47] |

|

Case report n = 5 patients, < 50 Y/A |

Large-vessel stroke Headache, dysarthria, numbness, hemiplegia, and reduced level of consciousness Not specific specimen |

[48] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient 41 Y/A |

Meningoencephalitis Seizure, lethargic, photophobia, worsening encephalopathy, disorientation, hallucinations, and neck stiffness Not specified specimen |

[49] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient 24 Y/A |

Meningitis/encephalitis fatigue and fever, vomit, seizures, unconsciousness, and neck stiffness Cerebral spinal fluid specimen |

[45] |

|

Retrospectively report n = 24 males and 19 females 16–85 Y/A |

Stroke and stroke with pulmonary thromboembolism Guillain-Barré syndrome Nasopharyngeal specimen |

[37] |

|

Case report n = 2 patients 52 Y/A male, 39 Y/A male |

Variants of Guillain-Barré syndrome Miller Fisher syndrome Diplopia, gait instability, headache, anosmia, and ageusia Polyneuritis cranialis and ageusia Oropharyngeal specimen |

[50] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient 61 Y/A female |

Acute Guillain-Barré syndrome Legs weakness and severe fatigue Oropharyngeal specimen |

[51] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient 65 Y/A male |

Guillain-Barré syndrome Acute progressive symmetric ascending quadriparesis, facial paresis bilaterally Oropharyngeal specimen |

[52] |

|

Case report n = 5 patients |

Guillain-Barré syndrome Nasopharyngeal specimen |

[53] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient |

Guillain-Barré syndrome Nasopharyngeal specimen |

[54] |

|

Case report n = 1 patient 58 Y/A female |

Acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy Altered mental status Nasopharyngeal specimen |

[55] |

Despite the evidence demonstrating the neurotropism of respiratory viruses, the exact mechanism of neuro-invasion accomplished by viruses remains currently unknown. However, the route of invasion of the CNS has recently been described for HCoV-OC-43. This virus gains access to the CNS through the olfactory bulb, moving along the olfactory nerve. Then, neuro-propagation occurs along the multiple axonal connections expanding through the CNS (e.g., neuron-to-neuron propagation or diffusing particles) [56]. Similar to HCoV-OC-43, a model in vivo of SARS-CoV infection suggested that the virus enters the brain via the olfactory bulb, and then, a transneuronal spread could occurs [57].

Also, some infectious blood-borne viruses primarily targeting peripheral organs have evolved strategies to thwart the blood-brain barrier (BBB). These strategies include direct infection of the brain microvascular endothelial cells that form the BBB, a paracellular entry that involves alteration of the tight junctions, or the “Trojan horse” invasion, via the traffic of infected monocytes/macrophages migrating across the BBB, in a similar manner as the not-respiratory immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) [58, 59]. Likewise, when human primary monocytes are activated following infection by HCoV-229E and eventually become macrophages, it can invade tissues, including the CNS [60, 61]. Additionally, it has been reported that through activation of the brain microendothelium, the damage caused by the inflammatory response, allows the virus to reach the CNS. In this sense, the neuro-invasion of SARS-CoV-2 could occur through trans-synaptic transfer, via the olfactory nerve, infection of vascular endothelium, or leukocyte migration across the BBB [38].

The SARS-CoV-2 Receptor

The cellular tropism of CoV depends on the location of its receptor which can be expressed in cells different from those of the respiratory system. Therefore, if SARS-CoV-2 has reached the CNS, the infection of brain cells depends on receptor recognition. It is the first step of viral infection and a key determinant of the host cell and tissue tropism. Walls et al. [62] reported that the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a metallopeptidase, mediates SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells, establishing it as a functional receptor for this recently appeared CoV. Previous studies achieved with SARS-CoV also showed that the binding affinity between viruses and human ACE2 correlates with increased virus transmissibility and disease severity in humans [63].

The human ACE2 protein is included within the renin angiotensin system (RAS) which is widely known for its physiological roles in electrolyte homeostasis, body fluid volume regulation, and cardiovascular control in the peripheral circulation. Renin, an enzyme produced from the kidney, acts on angiotensinogen (AGT), a liver precursor, to release angiotensin I (Ang I), an inactive decapeptide. Human ACE2 cleaves Ang I to convert it to the active octapeptide Ang II, the effector peptide of RAS, which is essential for various physiological functions [64].

The RAS has been described in various tissues such as the heart, the kidney, the lungs, the liver, the retina, and the brain [64, 65]. Chen et al. [66] screened the human ACE2 mRNA expression in human organs based on hGTEx database. They found that the digestive tract intestine displayed the highest expression of human ACE2, followed by the testis and the kidney. Consequently, the high vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2 to these organs could explain the positive detection of the virus in the patient’s feces and urine [67]. The expression of human ACE2 in the heart is lower than that in the intestine and kidney but higher than that in the lung, which serves as the main target organ for SARS-CoV-2, indicating a potential infection susceptibility of the human heart.

Unfortunately, there is relatively little information available on both the expression and regulation of RAS in the brain [68, 69]. Dzau et al. [70] demonstrated the expression of the ACE2 mRNA in mouse and rat brains using Northern blot analyses, although low levels of the human ACE2 mRNA were shown in the human brain using quantitative real-time RT-PCR [71, 72]. Chappell et al. [73] made the first demonstration of the endogenous presence of the ACE2 protein in brain tissues of rats using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and radioimmunoassays. Later, immunohistochemistry studies showed that human ACE2 protein was restricted to endothelial and arterial smooth muscle cells of cerebral vessels [74]. However, Lavoie et al. [68] produced double-transgenic mice which express the green fluorescent protein driven by the renin promoter and the β-galactosidase driven by the human angiotensin gene promoter and found that both proteins are co-expressed in the medulla, the pons, the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the hippocampus; additionally, other regions only expressed the ACE2 protein. Interestingly, ACE2 protein is predominant but not exclusive of neurons; astrocytes and glial cells also express it [68, 75, 76]. Additionally, it is possible that the brain endothelium expresses the ACE2 protein since recent studies demonstrated the susceptibility to the infection of endothelial cells in other tissues [66, 77].

The virus surface–anchored spike protein (S) mediates the SARS-CoV-2 entry to the target cell. Protein S contains a receptor-binging domain (RBD) that specifically recognizes the ACE2. The RBD shows a hidden position in SARS-CoV-2 that lead to poor recognition of the host receptor; however, this problem is overcome with an ACE2 high binding affinity and a furin motif that allows its spike to be pre-activated. Therefore, pro-protein convertase furin (PCF) plays an essential role in virus’ membrane fusion [78, 79]. PCF is a ubiquitously expressed subtilisin-related serine protease and member of the pro-protein convertase family that functions within the secretory and endocytic pathways and at the cell surface, cleaving pro-proteins. PCF has several substrates that include growth factors, receptors, coagulation proteins, plasma proteins, extracellular matrix components, and protease precursors (e.g., matrix metalloproteases). PCF activity contributes to numerous functions in CNS and also is involved in chronic pathological conditions [80]. PCF cleavage of viral envelope glycoproteins is necessary for the propagation of many lipid-enveloped viral pathogens. Accordingly, sequence alignment indicates that the PCF cleavage site in S protein is essential in CoV evolution [81]. Notably, the PCF cleavage site is involved in pathogenicity and modulates neuro-virulence. Some mutations in PCF induce severe encephalitis and break the BBB [82], while others lead to reduced neurotropism and limited dissemination within the CNS [83]. Therefore, evidence supports that SARS-CoV-2 can reach SNC and infect brain cells through S protein binding to ACE2 and modification by PCF.

SARS-CoV-2 and the Function of the BBB

The microvascular endothelial cells that form the BBB protect the CNS from a wide variety of toxins and microorganisms found in the blood. These cells express tight junction proteins that limit the movement between adjacent cells and are through specific transporters and receptor proteins that control entry and exit of molecules coming from the blood toward the brain parenchyma [84]. Therefore, the study of the damage induced to microvascular endothelial cells represents the central framework for understanding the molecular mechanisms of virus infection in the CNS [85, 86].

Disruption of the BBB occurs upon infection with several recognized neurotropic viruses. Arbovirus that belongs to the Flaviviridae family, such as the West Nile Virus and the Zika virus, can induce damage in the BBB caused by the host cell’s response to viral factors. Experiments carried out using in vitro and in vivo models of the BBB have demonstrated that these viruses replicate in the brain microvascular endothelial cells and induce down-regulation and degradation of tight junction proteins leading to disruption of the BBB [87–90]. Similarly, Bleau et al. [91] evaluated the ability of CoV to enter the CNS, using the highly hepatotropic mouse hepatitis virus type 3 and the weakly hepatotropic mouse hepatitis type A59. The type 3-infected mice showed brain invasion that correlated with enhanced BBB permeability. The effect was associated with decreased expression of the zona occludens protein 1, the VE-cadherin, and the occludin. Since CoV are molecularly related in its mode of replication, it is speculated that other types of CoV use a similar mechanism of action to infect the brain microvascular endothelial cells [92, 93]. Importantly, it has been identified the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the brain microvascular endothelial cells in frontal lobe tissue obtained at postmortem examination from a patient with COVID-19 [94]. Besides, viral particles and viral genome sequences of SARS-CoV have been detected in the cytoplasm of neurons of the brain, mainly in the hypothalamus and the cortex [44, 95]. This evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 crosses the BBB as well as others HCoV.

Therefore, infection by several respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, affects the integrity of the BBB through different mechanisms. The virus causes direct cell stress, associated with most of the cytotoxic effects that lead to degeneration of infected cells, for example, SARS-CoV induces apoptosis [96]. Endothelial cells activation as part of the inflammatory response causes an increase in the expression of proteases, such as matrix metalloproteinase, that promotes the degradation of the tight junction proteins [97]. However, it is probable that the inflammatory response plays the most important role in the induction of the damage to BBB.

The Inflammatory Response

The regular activity of neuroinflammation is mainly to restore the homeostasis in the brain [98]. However, prolonged CNS inflammation and systemic inflammatory response as a result of a wide variety of pathologies such as viral infections may influence the BBB integrity and further outcome in neurological disorders [99, 100]. Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 could cause damage to the BBB through the activation of the inflammatory immune response associated with a dysregulation around this process [101].

Activation of the microvascular endothelial cells has been associated with changes in BBB permeability. For example, during physiological conditions, immune cell migration into the CNS is rigorously controlled by mechanisms that operate at the level of the BBB. Notably, migration of circulating immune cells into the CNS is low and restricted to specific innate and adaptative immune cell subsets, such as lymphocytes, macrophages, and antigen presenting cells as dendritic cells that maintain immune surveillance in the CNS [102]. However, during viral infections, the migration of immune cells is increased. This is supported by histopathologic examination of the brain tissue in patients with SARS-CoV, where pathological infiltration of CD68+ monocytes/macrophages and CD3+ T lymphocytes has been found in the brain mesenchyme [95]. Similarly, the infiltration process, related to interactions between the β1 and β2 integrins expressed on leukocytes and their ligands [i.e., intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM): ICAM-1, ICAM-2, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1)] present on the surface of the microendothelial cells, that induce extravasation across the BBB under inflammatory conditions has been reported [103–107]. Evidence suggests that infection and activation of the microvascular endothelial cells by typical neurotrophic viruses increased endothelial adhesion molecules expression [88]. This condition facilitates the trafficking of viruses-infected immune cells into the CNS via the ‘Trojan horse’ mechanism [88].

Likewise, during viral replication in the host cells, the damage is caused because SARS-CoV-2 is a cytopathic virus that induces the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [108]. DAMPs are endogenous molecules released from damaged cells that interact with molecules called pattern-recognition receptor (PRR) that induce in the neighboring epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages a state of high inflammation [109].

Once the virus interacts with the host cells, the viral genome and viral proteins can also be recognized by PRRs and activated the immune response. Different PRRs recognize SARS-CoV-2, for example, the Toll-like receptors (TLR), which are molecules expressed in many cell lines, including endothelial cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 induce several pathways of activation that produce proinflammatory cytokines and other antiviral molecules to control the infection. However, this response can be dysregulated and exacerbated cytokines production [110]. Also, NOD-like receptor (NLR), other PRR, activates the inflammasome complex and induces the activation state in some cell types such as macrophages and epithelial and even in the microvascular endothelial cells leading to high production of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18. Nevertheless, this mechanism needs to be studied in detail for the new CoV [111].

On the other hand, the viral RNA activates typical molecules such as the retinoic acid inducible gene 1 and the melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 and induces an antiviral state, in which interferons (IFN) are secreted (mainly IFN type I and III). Interferons are molecules important to clearance the viral infection to prevent viruses from replicating [112, 113]. In patients with COVID-19, high levels of IFN, especially IFN I, are detected; this molecule blocks the viral replication in adjacent cells and produces some effects against the viral infection such as the induction of interferon-stimulated gene expression, the stimulation of cytokines production, and the activation of immune response cells (i.e., macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils) [112, 114]. Other CoV infections have a similar response [115, 116].

Furthermore, patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 have increased levels of several cytokines and chemokines: TNF-α, IFN-γ, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, and the granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; importantly, high levels of IL-6 have been linked to a worse prognosis in COVID-19 patients [116, 117]. This high production and misbalance of all these molecules is defined as cytokines storm (CS), which could be an essential factor to cause disruption of the BBB [110]. Interestingly, CS induces the activation of platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages; additionally, some of these molecules can interact with the complement and the coagulation systems and contribute to the pathogenic inflammation [117].

Furthermore, some chemokines can attract some innate immune response cells such as monocytes, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, and T cells [118] and induce the production others cytokines such as the monocyte chemotactic protein-1, the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, the macrophages inflammatory protein 1-α, and IL-10 that recruit lymphocytes and monocytes and initiate the humoral response. Together, all these mechanisms can contribute to the severity of neurological symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the BBB [30].

Other physiological disturbances in COVID-19 patients such as thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia (CD8+ T, CD4+ T, Treg cells, and platelets), and eosinopenia have also been describing. Blood samples and spleen and lymph nodes present these types of dysregulation due to the recruited cells to the infected sites to control the viral replication (Table 3) [119, 120]. Also, several patients present high levels of D-dimer in the early stage of the infection (Table 3). This molecule is an important marker in the disorder of coagulation. It represents a thrombotic state that leads to embolic vascular events and can produce venous clots and induce brain damage [121]. Therefore, COVID-19 patients with high inflammation trigger excessive thrombin production that inhibits fibrinolysis and activates the complement pathways leading thromboinflammation, microthrombin deposition, and microvascular dysfunction associated with damage of the BBB [122, 123].

Table 3.

Laboratory findings in neurological manifestation in COVID-19

| Author | Manifestation | Laboratory finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avula et al. | Stroke | - Lymphopenia | [46, 48] |

| - Elevated C-reactive [26 mg/dl (0.04 mg/dl)] | |||

| - Elevated D-dimer [mean 8704 ng/ml (< 880 ng/ml) | |||

| - Elevated lactate dehydrogenase (712 U/L) | |||

| Oxley et al. | - D-dimer [5972 ng/ml (0–500 ng/ml)] | ||

| Moringuchi et al. | Meningoencephalitis | - Elevated neutrophil | [45] |

| - Increased C-reactive protein | |||

| Guitierrez-Ortiz et al. | Guillain-Barré syndrome | - Lymphopenia (1000 cells/μl) | [50, 51, 54] |

| - Leucopenia (3100/cells/μl) | |||

| - Elevated C-reactive protein (2.8 mg/dl) | |||

| - Positive GD1b-IgG ganglioside antibody | |||

| Virani et al. | - Lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia | ||

| Zhao et al. | - Lymphocytopenia [0.52 × 109/L (1.1–3.2 × 109/L)] | ||

| - Thrombocytopenia [113 × 109/L (125–3000 × 109/L)] |

An unexplored mechanism that could produce damage in the BBB is the adaptative immune response. The generation of antibodies (Abs) against SARS-CoV-2 can cross-react with some molecules of the brain microvascular endothelial cells and produce damage through the activation of the complement system (C3 and C4 proteins). Also, Ab-dependent enhancement phenomenon can increase the infection and contribute to the injury. This process has been extensively studied in Dengue and Zika virus infection, where the Abs produced in the first exposure can cross-react in a second exposure and enhance the infection instead of neutralizing it [124, 125]. Additionally, the Abs can generate an autoimmune attack and interact with the virus forming immune complexes and induce the complement system activation [126].

Recently, some studies showed that the cellular immune response could be central to determine the disease condition. Several viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, can activate CD4+ and CD8+ and induce clonal expansion, specific cell effectors, and cellular memory [127, 128]. Also, T cells can cross-react inducing a state of protection observed in unexposed people with SARS-CoV-2 [129, 130]. Finally, more studies around the interaction with SARS-CoV-2 and the host immune system need to be clarified. Research around the mechanisms involved in inflammation response can allow the development of strategies that might help to mitigate the health consequence of this pandemic.

Neurological Implications of BBB Disruption by SARS-CoV-2

As previously discussed, multiple respiratory viruses can affect the CNS. For example, the mouse hepatitis virus induces inflammation, BBB damage, and demyelination in rat models [131]. Likewise, a case report of HCoV-OC43 detected in nasopharyngeal and cerebral spinal fluid samples from a child patient exhibited acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, a low-prevalence CNS disease that induces demyelination [132]. The H1N1 virus, the causative agent of high mortality rates, also presented neurological complications. A retrospective study of the clinical files of 55 patients infected with H1N1 detected 50% of visible neurological symptoms [133]. Interestingly, most patients with neurological manifestations due to H1N1 infection manifested brain edema [134]. Importantly, in autopsy studies, patients with SARS-CoV showed endothelial activation associated with the loss of cerebral vascular integrity displaying multifocal hemorrhage [135]. Histological examination of brain tissue specimens of patients with SARS-CoV infection also showed neuronal degeneration, necrosis, edema, extensive glial cell hyperplasia, and cellular infiltration of the vascular walls by monocytes and lymphocytes [40].

With this background, several studies have attempted to characterize the neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2. An increasing number of individual case reports have emerged describing acute neurological disorders ranging from Guillain-Barré syndrome and acute myelitis to acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy [136]. Although the long-term neurological implications of SARS-CoV-2 infection are still unknown, important clues suggest that complications of the disease are related to CNS invasion by damaging the BBB.

Neurological Implications of BBB Disruption by SARS-CoV-2 in Long-Term Dementia

There is a very complex interaction between the brain cells and the cerebral vasculature. Consequently, preservation of the cerebrovascular function and its integrity has a central role in this sophisticated communication. Additionally, any derangements can have deleterious acute and chronic consequences such as the development of neurodegenerative diseases and dementia [137].

Infectious agents have been suspected as contributing factors to dementia, especially in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Interestingly, the BBB disruption appears to be an early feature of this disease [138]. For instance, Bell et al. [139] demonstrated that BBB breakdown was derived in neurotoxic proteins infiltration (e.g., amyloid-β peptides, the hallmark of AD), affecting neurons and either initiating or exacerbating neurodegeneration. Also, Ueno et al. [140] using experimental animal models exhibiting some phenotypes of vascular dementia showed that BBB damage might be related to amyloid-β peptides accumulation. Accordingly, damage induced to the BBB by infectious agents might trigger neurodegenerative diseases in predisposed patients [141]. Therefore, viral infections such as SARS-CoV-2 could be associated with an increased risk of AD development and a faster rate of cognitive decline in older populations.

AD in systemic virus infection is an example of a condition that is primarily neurodegenerative; however, in many cases, it is not clear whether BBB changes are the cause or the effect of a neuropathology. Furthermore, it is possible that the BBB anomalies and the disease drive each other in a self-perpetuating manner, contributing to damage progression [142]. As mentioned, acute and chronic systemic inflammation accelerates the progress of AD [143]. Also, a 5-year follow-up study showed that viral infections, like the induced by cytomegalovirus, are linked with faster cognitive decline and development of AD [144]. Furthermore, systemic inflammation in AD is associated with several BBB changes, which further favor amyloid-β peptides accumulation into the brain because the injury alters the influx and efflux of the peptides [145]; correspondingly, systemic inflammation accelerates hippocampal amyloid-β peptides deposition [146]. Therefore, dysfunction of the BBB might play a significant role in the pathogenesis of vascular dementia induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection, but further observations are needed.

Additionally, damage to the BBB is not the only mechanism where SARS-CoV-2 infection can result in dementia. Some data suggest that amyloid-β protein possesses antimicrobial and antiviral activity in vitro [147]. Therefore, the presence of insoluble deposits of amyloid-β peptides could be a factor (e.g., genetic predisposing) that alter the response to viral SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, it is conceivable that SARS-CoV-2 contributes to BBB damage and also creates a feed-forward effect whereby pathogen-induced damage favors a further spread of the pathogen’s transit zones and even the sequential development of the pathology associated to AD [138].

On the other hand, individuals with AD are more vulnerable to the effects of peripheral infection, especially SARS-CoV-2, mainly due to the association of physical comorbidities. It is more probable that these individuals have cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and pneumonia [148]. Besides, there is an overall decrease in naive T cell diversity after the age of 65 [149–151]; this can limit the capacity of the individual to induce a sufficient immune response to infection. Together, these data indicate the vulnerability of these patients to infection.

Neurological Implications of BBB Disruption by SARS-CoV-2 in Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the CNS, characterized by several pathological processes, including inflammation, trans-endothelial migration, demyelination, axonopathy, and neuron loss mediated by immune cells [152]. MS represents a neurological disease where an infectious agent plays a triggering role, being viruses the most likely culprit in genetically predisposed individuals [141]. There is a presumption that several neurotropic viruses using similar mechanisms could be involved in MS pathogenesis [153]. Some viruses that have been implicated in the development of MS include herpes viruses, paramyxoviruses, picornaviruses, as well as viruses that classically affect the respiratory system such as influenza virus [154].

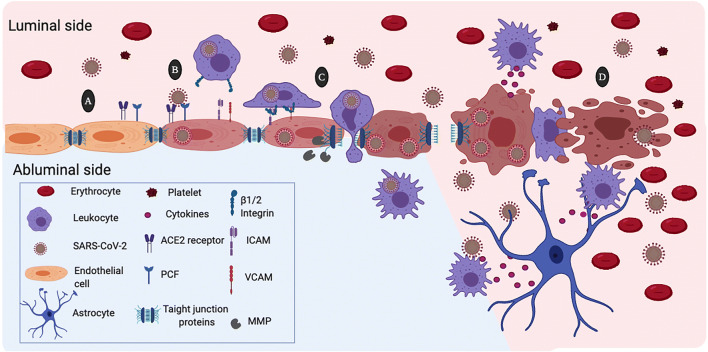

A critical step in the pathogenesis of MS is the infiltration of autoreactive CD4+ T-lymphocytes into the CNS after activation in the periphery. Evaluation of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), Th1 cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-12), and Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10) in sera collected from SARS patients within 2 days of hospital admission showed a substantial elevation of IL-12, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IFN-γ [155]. Also, Sonar et al. [156] revealed that IFN-γ favored the trans-endothelial migration of CD4+ T cells from the apical (luminal side) to the basal side (abluminal side) of the endothelial monolayer (Fig. 2). Besides, using multicolor immunofluorescence and confocal microscopic analysis, these authors indicated that IFN-γ induce relocalization of ICAM-1, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, zona occludens protein 1, and VE-cadherin in the endothelial cells. These findings reveal that the IFN-γ produced during the response to infection and inflammation could contribute to the disruption of the BBB and promote CD4+ T cells brain migration. Interestingly, BBB disruption appears in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a typical MS model, and the clinical severity is linked to the degree of BBB integrity [157]. Furthermore, imaging studies showed BBB disruption in normal-appearing white matter in MS [158]. This data is important since BBB breakdown precedes the development of new MS lesions [159]. In summary, it is possible that the damage caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection to the endothelial cells also causes loss of the BBB integrity, favoring MS progression.

Fig. 2.

Possible mechanism of damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by the action of SARS-CoV-2. a Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the pro-protein convertase furin (PCF) in the membrane of the brain microvascular endothelial cells facilitates SARS-CoV-2 infection. b SARS-CoV2 infection activates the brain microendothelial cells inducing high expression of the vascular and the intercellular adhesion molecules (VCAM and ICAM). Likewise, SARS-CoV-2 induces the expression and activation matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) that degrade tight junctions proteins. c Recognition of ICAM and ICAM through the β1 and β2 integrins causes binding of circulating leukocytes to endothelial cells that lead transcellular extravasation. This process facilitate viral entrance to the cerebral parenchyma through the “Trojan horse” mechanism. d SARS-CoV-2 viral replication induces endothelial cell contraction and lysis. Increased permeability of the BBB allows extravasation of plasma proteins and blood cells. Activation of leukocytes and platelets contributes to the BBB damage. Besides, endothelial cell death disturbs the microenvironment of the brain parenchyma allowing free passage of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and infection of other cells of the central nervous system

Conclusion

Recent information has shown the SARS-CoV-2 ability to infect CNS cells, especially the brain microvascular endothelial cells of the BBB. This situation explains the neurological symptoms observed during infection and reveals the possible consequences of viral infection. Although it is too early to elucidate the long-term side effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the background obtained with other respiratory viruses suggests that SARS-CoV-2 might induce permanent sequelae in the CNS through damage to the BBB, including dementia in predisposed patients. Furthermore, the proinflammatory state, due to viral infection seems to be the general mechanism involved in the induction of BBB damage. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this evidence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) for the scholarship No. 413994 assigned to Iván M. Alquisiras Burgos, doctoral student from Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biomédicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). We also thank the postdoctoral fellowship program DGAPA-UNAM assigned to Irlanda Peralta Arrieta at FES-Iztacala, UBIMED, and postdoctoral fellowship N° SECTEI/138/2019 from Mexico City assigned to Luis Alonso Palomares.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to research data and discussion of the content, wrote and reviewed the article, and edited the manuscript before submission.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forni D, Cagliani R, Clerici M, Sironi M. Molecular evolution of human coronavirus genomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25(1):35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai ACK, Zhou J, Liu W, Bi Y, Gao GF. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt H-R, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RAM, Berger A, Burguière A-M, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra J-C, Müller S, Rickerts V, Stürmer M, Vieth S, Klenk H-D, Osterhaus ADME, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen Y-M, Wang W, Song Z-G, Hu Y, Tao Z-W, Tian J-H, Pei Y-Y, Yuan M-L, Zhang Y-L, Dai F-H, Liu Y, Wang Q-M, Zheng J-J, Xu L, Holmes EC, Zhang Y-Z. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, To KK-W. Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC-Y, Poon RW-S, Tsoi H-W, Lo SK-F, Chan K-H, Poon VK-M, Chan W-M, Ip JD, Cai J-P, Cheng VC-C, Chen H, Hui CK-M, Yuen K-Y. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si H-R, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang C-L, Chen H-D, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang R-D, Liu M-Q, Chen Y, Shen X-R, Wang X, Zheng X-S, Zhao K, Chen Q-J, Deng F, Liu L-L, Yan B, Zhan F-X, Wang Y-Y, Xiao G-F, Shi Z-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam TT-Y, Shum MH-H, Zhu H-C, Tong Y-G, Ni X-B, Liao Y-S, Wei W, Cheung WY-M, Li W-J, Li L-F, Leung GM, Holmes EC, Hu Y-L, Guan Y. Identification of 2019-nCoV related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins in southern China. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.2002.2013:945485. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.13.945485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, Zhou N, Zhang X, Zou J-J, Li N, Guo Y, Li X, Shen X, Zhang Z, Shu F, Huang W, Li Y, Zhang Z, Chen R-A, Wu Y-J, Peng S-M, Huang M, Xie W-J, Cai Q-H, Hou F-H, Chen W, Xiao L, Shen Y. Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583(7815):286–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Biol. 2020;30(7):1346–1351.e1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Gayle AA, Wilder-Smith A, Rocklöv J (2020) The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med 27(2). 10.1093/jtm/taaa021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Chen J. Pathogenicity and transmissibility of 2019-nCoV—A quick overview and comparison with other emerging viruses. Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Liao X, Qian S, Yuan J, Wang F, Liu Y, Wang Z, Wang FS, Liu L, Zhang Z. Community transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Shenzhen, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1320–1323. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong SWX, Tan YK, Chia PY, Lee TH, Ng OT, Wong MSY, Marimuthu K. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):589–594. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1831–1833.e1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z-M, Fu J-F, Shu Q. New coronavirus: new challenges for pediatricians. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):222–222. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00346-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z-M, Fu J-F, Shu Q, Chen Y-H, Hua C-Z, Li F-B, Lin R, Tang L-F, Wang T-L, Wang W, Wang Y-S, Xu W-Z, Yang Z-H, Ye S, Yuan T-M, Zhang C-M, Zhang Y-Y. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):240–246. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun D, Li H, Lu X-X, Xiao H, Ren J, Zhang F-R, Liu Z-S. Clinical features of severe pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan: a single center's observational study. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):251–259. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei M, Yuan J, Liu Y, Fu T, Yu X, Zhang Z-J. Novel coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1313–1314. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.W-j G, Ni Z-y HY, Liang W-h, C-q O, He J-x, Liu L, Shan H, C-l L, Hui DSC, Du B, L-j L, Zeng G, Yuen K-Y, R-c C, C-l T, Wang T, P-y C, Xiang J, S-y L, Wang J-l, Liang Z-j, Y-x P, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu Y-h, Peng P, Wang J-m, J-y L, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng Z-j, S-q Q, Luo J, C-j Y, Zhu S-y, N-s Z. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, Satlin MJ, Campion TR, Nahid M, Ringel JB, Hoffman KL, Alshak MN, Li HA, Wehmeyer GT, Rajan M, Reshetnyak E, Hupert N, Horn EM, Martinez FJ, Gulick RM, Safford MM. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, Lang C, Huang D, Sun Q, Xiong Y, Huang X, Lv J, Luo Y, Shen L, Yang H, Huang G, Yang R. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in Northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):797–806. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Tang Y, Mo Y, Li S, Lin D, Yang Z, Yang Z, Sun H et al (2020) A diagnostic model for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based on radiological semantic and clinical features: A multi-center study. Eur Radiol. 10.1007/s00330-020-06829-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Cheng Z, Lu Y, Cao Q, Qin L, Pan Z, Yan F, Yang W. Clinical features and chest CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a single-center study in Shanghai, China. Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215(1):121–126. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eliezer M, Hautefort C, Hamel A-L, Verillaud B, Herman P, Houdart E, Eloit C. Sudden and complete olfactory loss of function as a possible symptom of COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(7):674–675. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klopfenstein T, Kadiane-Oussou NJ, Toko L, Royer PY, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, Zayet S. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50(5):436–439. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, Nortley R, Wiethoff S, Bharucha T, Jayaseelan DL, Kumar G, Raftopoulos RE, Zambreanu L, Vivekanandam V, Khoo A, Geraldes R, Chinthapalli K, Boyd E, Tuzlali H, Price G, Christofi G, Morrow J, McNamara P, McLoughlin B, Lim ST, Mehta PR, Levee V, Keddie S, Yong W, Trip SA, Foulkes AJM, Hotton G, Miller TD, Everitt AD, Carswell C, Davies NWS, Yoong M, Attwell D, Sreedharan J, Silber E, Schott JM, Chandratheva A, Perry RJ, Simister R, Checkley A, Longley N, Farmer SF, Carletti F, Houlihan C, Thom M, Lunn MP, Spillane J, Howard R, Vincent A, Werring DJ, Hoskote C, Jäger HR, Manji H, Zandi MS. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: Clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain J Neurol. 2020;8:awaa240. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: A review. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):1018–1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohmwald K, Gálvez NMS, Ríos M, Kalergis AM (2018) Neurologic alterations due to respiratory virus infections. Front Cell Neurosci 12(386). 10.3389/fncel.2018.00386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Ding Y, Wang H, Shen H, Li Z, Geng J, Han H, Cai J, Li X, Kang W, Weng D, Lu Y, Wu D, He L, Yao K. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): A report from China. J Pathol. 2003;200(3):282–289. doi: 10.1002/path.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montalvan V, Lee J, Bueso T, De Toledo J, Rivas K. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 and other coronavirus infections: a systematic review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;194:105921. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arbour N, Côté G, Lachance C, Tardieu M, Cashman NR, Talbot PJ. Acute and persistent infection of human neural cell lines by human coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 1999;73(4):3338–3350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.4.3338-3350.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacomy H, Talbot PJ. Vacuolating encephalitis in mice infected by human coronavirus OC43. Virology. 2003;315(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, Zou W, Zhan J, Wang S, Xie Z, Zhuang H, Wu B, Zhong H, Shao H, Fang W, Gao D, Pei F, Li X, He Z, Xu D, Shi X, Anderson VM, Leong ASY. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, Sakata H, Kondo K, Myose N, Nakao A, Takeda M, Haro H, Inoue O, Suzuki-Inoue K, Kubokawa K, Ogihara S, Sasaki T, Kinouchi H, Kojin H, Ito M, Onishi H, Shimizu T, Sasaki Y, Enomoto N, Ishihara H, Furuya S, Yamamoto T, Shimada S. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avula A, Nalleballe K, Narula N, Sapozhnikov S, Dandu V, Toom S, Glaser A, Elsayegh D. COVID-19 presenting as stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al Saiegh F, Ghosh R, Leibold A, Avery MB, Schmidt RF, Theofanis T, Mouchtouris N, Philipp L, Peiper SC, Wang Z-X, Rincon F, Tjoumakaris SI, Jabbour P, Rosenwasser RH, Gooch MR. Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery &. Psychiatry. 2020;91(8):846–848. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, De Leacy RA, Shigematsu T, Ladner TR, Yaeger KA, Skliut M, Weinberger J, Dangayach NS, Bederson JB, Tuhrim S, Fifi JT. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duong L, Xu P, Liu A. Meningoencephalitis without respiratory failure in a young female patient with COVID-19 infection in downtown Los Angeles, early April 2020. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:33–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Méndez-Guerrero A, Rodrigo-Rey S, San Pedro-Murillo E, Bermejo-Guerrero L, Gordo-Mañas R, de Aragón-Gómez F, Benito-León J. Miller fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology. 2020;95(5):e601–e605. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao H, Shen D, Zhou H, Liu J, Chen S. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):383–384. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sedaghat Z, Karimi N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: a case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;76:233–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, Ruiz L, Invernizzi P, Cuzzoni MG, Franciotta D, Baldanti F, Daturi R, Postorino P, Cavallini A, Micieli G. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2574–2576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Virani A, Rabold E, Hanson T, Haag A, Elrufay R, Cheema T, Balaan M, Bhanot N. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. IDCases. 2020;20:e00771–e00771. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID-19–associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: imaging features. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E119–E120. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubé M, Le Coupanec A, Wong AHM, Rini JM, Desforges M, Talbot PJ. Axonal transport enables neuron-to-neuron propagation of human coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 2018;92(17):e00404–e00418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00404-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spindler KR, Hsu TH. Viral disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20(6):282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albright AV, Soldan SS, González-Scarano F. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus-induced neurological disease. J Neuro-Oncol. 2003;9(2):222–227. doi: 10.1080/13550280390194073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Desforges M, Miletti TC, Gagnon M, Talbot PJ. Activation of human monocytes after infection by human coronavirus 229E. Virus Res. 2007;130(1–2):228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Z, Liu T, Yang N, Han D, Mi X, Li Y, Liu K, Vuylsteke A et al (2020) Neurological manifestations of patients with COVID-19: potential routes of SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion from the periphery to the brain. Front Med:1–9. 10.1007/s11684-020-0786-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Walls AC, Park Y-J, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292.e286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li W, Zhang C, Sui J, Kuhn JH, Moore MJ, Luo S, Wong S-K, Huang IC, Xu K, Vasilieva N, Murakami A, He Y, Marasco WA, Guan Y, Choe H, Farzan M. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005;24(8):1634–1643. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abiodun OA, Ola MS. Role of brain renin angiotensin system in neurodegeneration: An update. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(3):905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ou Z, Jiang T, Gao Q, Tian Y-Y, Zhou J-S, Wu L, Shi J-Q, Zhang Y-D. Mitochondrial-dependent mechanisms are involved in angiotensin II-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2016;17(4):1470320316672349. doi: 10.1177/1470320316672349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen R, Wang K, Yu J, Chen Z, Wen C, Xu Z (2020) The spatial and cell-type distribution of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in human and mouse brain. bioRxiv:2020.2004.2007.030650. doi:10.1101/2020.04.07.030650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G, Tan W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lavoie JL, Cassell MD, Gross KW, Sigmund CD. Adjacent expression of renin and angiotensinogen in the rostral ventrolateral medulla using a dual-reporter transgenic model. Hypertension. 2004;43(5):1116–1119. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000125143.73301.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stornetta RL, Hawelu-Johnson CL, Guyenet PG, Lynch KR. Astrocytes synthesize angiotensinogen in brain. Science (New York, NY) 1988;242(4884):1444–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.3201232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dzau VJ, Ingelfinger J, Pratt RE, Ellison KE. Identification of renin and angiotensinogen messenger RNA sequences in mouse and rat brains. Hypertension. 1986;8(6):544–548. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.8.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gembardt F, Sterner-Kock A, Imboden H, Spalteholz M, Reibitz F, Schultheiss H-P, Siems W-E, Walther T. Organ-specific distribution of ACE2 mRNA and correlating peptidase activity in rodents. Peptides. 2005;26(7):1270–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, Clark KL. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2002;532(1):107–110. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chappell MC, Brosnihan KB, Diz DI, Ferrario CM. Identification of angiotensin-(1-7) in rat brain. Evidence for differential processing of angiotensin peptides. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(28):16518–16523. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)84737-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bodiga VL, Bodiga S. Renin angiotensin system in cognitive function and dementia. Asian J Neurosci. 2013;2013:102602. doi: 10.1155/2013/102602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gowrisankar YV, Clark MA. Angiotensin II regulation of angiotensin-converting enzymes in spontaneously hypertensive rat primary astrocyte cultures. J Neurochem. 2016;138(1):74–85. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Albini A, Di Guardo G, Noonan DM, Lombardo M. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE-2, is expressed on many different cell types: implications for ACE-inhibitor- and angiotensin II receptor blocker-based cardiovascular therapies. Intern Emerg Med. 2020;15(5):759–766. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bestle D, Heindl MR, Limburg H, van TVL, Pilgram O, Moulton H, Stein DA, Hardes K, Eickmann M, Dolnik O, Rohde C, Becker S, Klenk H-D, Garten W, Steinmetzer T, Böttcher-Friebertshäuser E (2020) TMPRSS2 and furin are both essential for proteolytic activation and spread of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway epithelial cells and provide promising drug targets. bioRxiv:2020.2004.2015.042085. doi:10.1101/2020.04.15.042085

- 79.Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, Geng Q, Auerbach A, Li F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581(7807):221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thomas G. Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(10):753–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jin X, Xu K, Jiang P, Lian J, Hao S, Yao H, Jia H, Zhang Y, Zheng L, Zheng N, Chen D, Yao J, Hu J, Gao J, Wen L, Shen J, Ren Y, Yu G, Wang X, Lu Y, Yu X, Yu L, Xiang D, Wu N, Lu X, Cheng L, Liu F, Wu H, Jin C, Yang X, Qian P, Qiu Y, Sheng J, Liang T, Li L, Yang Y. Virus strain from a mild COVID-19 patient in Hangzhou represents a new trend in SARS-CoV-2 evolution potentially related to Furin cleavage site. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1474–1488. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1781551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheng J, Zhao Y, Xu G, Zhang K, Jia W, Sun Y, Zhao J, Xue J, Hu Y, Zhang G. The S2 subunit of QX-type infectious bronchitis coronavirus spike protein is an essential determinant of Neurotropism. Viruses. 2019;11(10):972. doi: 10.3390/v11100972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Le Coupanec A, Desforges M, Meessen-Pinard M, Dubé M, Day R, Seidah NG, Talbot PJ. Cleavage of a neuroinvasive human respiratory virus spike glycoprotein by proprotein convertases modulates neurovirulence and virus spread within the central nervous system. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(11):e1005261–e1005261. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood–brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282(21):4067–4079. doi: 10.1111/febs.13412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Besancon E, Guo S, Lok J, Tymianski M, Lo EH. Beyond NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors: Emerging mechanisms for ionic imbalance and cell death in stroke. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(5):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O'Donnell ME. Chapter four - blood–brain barrier Na transporters in ischemic stroke. In: Davis TP, editor. Advances in Pharmacology. Cambridge: Academic press; 2014. pp. 113–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chiu C-F, Chu L-W, Liao I-C, Simanjuntak Y, Lin Y-L, Juan C-C, Ping Y-H (2020) The mechanism of the Zika virus crossing the placental barrier and the blood-brain barrier. Front Microbiol 11(214). 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Verma S, Lo Y, Chapagain M, Lum S, Kumar M, Gurjav U, Luo H, Nakatsuka A, Nerurkar VR. West Nile virus infection modulates human brain microvascular endothelial cells tight junction proteins and cell adhesion molecules: Transmigration across the in vitro blood-brain barrier. Virology. 2009;385(2):425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leda AR, Bertrand L, Andras IE, El-Hage N, Nair M, Toborek M. Selective disruption of the blood-brain barrier by Zika virus. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2158. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wells AI, Coyne CB. Type III interferons in antiviral defenses at barrier surfaces. Trends Immunol. 2018;39(10):848–858. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bleau C, Filliol A, Samson M, Lamontagne L. Brain invasion by mouse hepatitis virus depends on impairment of tight junctions and beta interferon production in brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Virol. 2015;89(19):9896–9908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01501-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Brison E, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;807:75–96. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-1777-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guo Y, Korteweg C, McNutt MA, Gu J. Pathogenetic mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, Gordon RE, Reidy J, Lednicky J, Sordillo EM, Fowkes M. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):699–702. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu J, Zhong S, Liu J, Li L, Li Y, Wu X, Li Z, Deng P, Zhang J, Zhong N, Ding Y, Jiang Y. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the brain: Potential role of the chemokine mig in pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(8):1089–1096. doi: 10.1086/444461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Stodola JK, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Human coronaviruses: Viral and cellular factors involved in neuroinvasiveness and neuropathogenesis. Virus Res. 2014;194:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suen WW, Prow NA, Hall RA, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Mechanism of West Nile virus neuroinvasion: a critical appraisal. Viruses. 2014;6(7):2796–2825. doi: 10.3390/v6072796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xanthos DN, Sandkühler J. Neurogenic neuroinflammation: inflammatory CNS reactions in response to neuronal activity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(1):43–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Almutairi MM, Gong C, Xu YG, Chang Y, Shi H. Factors controlling permeability of the blood-brain barrier. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(1):57–77. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Erickson MA, Dohi K, Banks WA. Neuroinflammation: a common pathway in CNS diseases as mediated at the blood-brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2012;19(2):121–130. doi: 10.1159/000330247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang H, Zhou P, Wei Y, Yue H, Wang Y, Hu M, Zhang S, Cao T, Yang C, Li M, Guo G, Chen X, Chen Y, Lei M, Liu H, Zhao J, Peng P, Wang C-Y, Du R. Histopathologic changes and SARS-CoV-2 immunostaining in the lung of a patient with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(9):629–632. doi: 10.7326/M20-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Engelhardt B, Ransohoff RM. Capture, crawl, cross: the T cell code to breach the blood–brain barriers. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(12):579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gorina R, Lyck R, Vestweber D, Engelhardt B. β<sub>2</sub> integrin–mediated crawling on endothelial ICAM-1 and ICAM-2 is a prerequisite for transcellular neutrophil diapedesis across the inflamed blood–brain barrier. J Immunol. 2014;192(1):324–337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hermand P, Huet M, Callebaut I, Gane P, Ihanus E, Gahmberg CG, Cartron JP, Bailly P. Binding sites of leukocyte beta 2 integrins (LFA-1, mac-1) on the human ICAM-4/LW blood group protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(34):26002–26010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Majerova P, Michalicova A, Cente M, Hanes J, Vegh J, Kittel A, Kosikova N, Cigankova V, Mihaljevic S, Jadhav S, Kovac A. Trafficking of immune cells across the blood-brain barrier is modulated by neurofibrillary pathology in tauopathies. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0217216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Randi AM, Hogg N. I domain of beta 2 integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 contains a binding site for ligand intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(17):12395–12398. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99884-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.van Wetering S, van den Berk N, van Buul JD, Mul FP, Lommerse I, Mous R, ten Klooster JP, Zwaginga JJ, Hordijk PL. VCAM-1-mediated Rac signaling controls endothelial cell-cell contacts and leukocyte transmigration. Am J Phys Cell Phys. 2003;285(2):C343–C352. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00048.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Park WB, Kwon NJ, Choi SJ, Kang CK, Choe PG, Kim JY, Yun J, Lee GW, Seong MW, Kim NJ, Seo JS, Oh MD. Virus isolation from the first patient with SARS-CoV-2 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(7):e84. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yilla M, Harcourt BH, Hickman CJ, McGrew M, Tamin A, Goldsmith CS, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ. SARS-coronavirus replication in human peripheral monocytes/macrophages. Virus Res. 2005;107(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azkur D, Sokolowska M, van de Veen W, Brüggen M-C, O'Mahony L, Gao Y, Nadeau K, Akdis CA. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]