Abstract

Background

Black and Latina women in New York City are twice as likely to experience a potentially life-threatening morbidity during childbirth than White women. Health care quality is thought to play a role in this stark disparity, and patient-provider communication is one aspect of health care quality targeted for improvement. Perceived health care discrimination may influence patient-provider communication but has not been adequately explored during the birth hospitalization.

Purpose

Our objective was to investigate the impact of perceived racial-ethnic discrimination on patient-provider communication among Black and Latina women giving birth in a hospital setting.

Methods

We conducted four focus groups of Black and Latina women (n=27) who gave birth in the past year at a large hospital in New York City. Moderators of concordant race/ethnicity asked a series of questions on the women’s experiences and interactions with health care providers during their birth hospitalizations. One group was conducted in Spanish. We used an integrative analytic approach. We used the behavioral model for vulnerable populations adapted for critical race theory as a starting conceptual model. Two analysts deductively coded transcripts for emergent themes, using constant comparison method to reconcile and refine code structure. Codes were categorized into themes and assigned to conceptual model categories.

Results

Predisposing patient factors in our conceptual model were intersectional identities (eg, immigrant/Latina or Black/Medicaid recipient), race consciousness (“…as a woman of color, if I am not assertive, if I am not willing to ask, then they will not make an effort to answer”), and socially assigned race (eg, “what you look like, how you talk”). We classified themes of differential treatment as impeding factors, which included factors overlooked in previous research, such as perceived differential treatment due to the relationship with the infant’s father and room assignment. Themes for differential treatment co-occurred with negative provider communication attributes (eg, impersonal, judgmental) or experience (eg, not listened to, given low priority, preferences not respected).

Conclusions

Perceived racial-ethnic discrimination during childbirth influences patient-provider communication and is an important and potentially modifiable aspect of the patient experience. Interventions to reduce obstetric health care disparities should address perceived discrimination, both from the provider and patient perspectives.

Keywords: Racial Discrimination, Health Care, Communication, Obstetrics

Introduction

Racial-ethnic disparities in maternal mortality are currently in the spotlight and health care is under scrutiny.1 We found that Black and Latina women in New York City were three and two times as likely as White women to experience severe maternal morbidity, defined as a potentially life-threatening event, during childbirth.2,3 Moreover, we found that Black and Latina women within hospitals were at higher risk than White women even after risk-adjustment, pointing to the need to investigate sources of differential quality of care.4 Evidence exists that Black and Latina women are also at increased risk of other adverse outcomes that may be influenced in part by obstetric care,5 including cesarean delivery,6 pain management,7 and postpartum health.8 Provider bias9 and communication10 have been proposed as potential targets for hospital-based interventions, yet evidence linking these factors to maternal health care disparities is lacking.

Perceived racial-ethnic discrimination in health care, defined as a patient’s perception of the differential allocation or quality of services based on race or ethnicity, is recognized as an important factor in health care quality.11,12 Racial-ethnic discrimination not specific to health care and its adverse impact on pregnancy outcomes is well-explored.13 In contrast, perceived racial-ethnic discrimination in the obstetric health care setting has received little attention. One survey found twice as many Black and Latina women as White women were treated poorly, and that poorer treatment was associated with provider communication during prenatal care, but did not examine communication during childbirth.14 Previous qualitative research in California regarding women’s experiences of health care during pregnancy and child birth has revealed perceived differential treatment and communication among women of color.15,16 However, these studies had a broad scope and did not focus specifically on childbirth hospitalization. Given the current focus on provider bias and communication as targets for intervention in maternity hospitals,9,10 a deeper understanding of how Black and Latina women perceive differential treatment during childbirth and how these perceptions impact communication is needed.

Our objective was to investigate patient-provider communication during childbirth among Black and Latina women from the perspective of Critical Race Theory (CRT). CRT focuses on the social construction of race and recognizes the pervasiveness of structural racism.17 CRT has gained traction as a framework by population health researchers to understand the influence of race and ethnicity on health,18-20 and has been suggested as a lens to understand relationship‐centered care and improve clinical experiences for pregnant Black people.21 As a starting conceptual framework, we incorporated three CRT concepts – intersectionality, race consciousness, and socially assigned race – into a common model of health care use, the behavioral model for vulnerable populations (BMVP).18 Intersectionality posits that multiple identities such as race, gender and class can form unique identities to reflect interlocking systems of privilege and oppression.22 Race consciousness is one’s explicit acknowledgment of the workings of race and racism in social contexts,18 and may be important in the perception of racial discrimination.23,24 Finally, socially assigned race, or the social interpretation of how one looks, may be important in understanding patient-provider interaction.25 We posited that analyzing Black and Latina women’s experiences of care during their birth hospitalization through the CRT lens would elucidate mechanisms by which perceived health care discrimination influence patient-provider communication.

Methods

We conducted four focus groups (n=27). Two groups of Black women were conducted in English, one group of Latina women was conducted in English, and a second in Spanish. Eligibility criteria included: gave birth in the past year; spoke English or Spanish; and self-identified as either Black or Latina. We sent invitation letters to women who gave birth in the study hospital in 2018 and who also attended prenatal care at the same hospital’s clinic, which serves women with public insurance. Interested women emailed or called the study coordinator and were screened for eligibility. Participants were offered a $100 gift card for their participation. All materials were translated into Spanish.

The focus groups took place in the study hospital in an area of the floor separate from patient care. The study moderators consented the women prior to the start of the focus group and collected demographic information. Groups lasted from 90 minutes to 2 hours. Discussions were recorded, transcribed, and translated to English (when applicable).

The research team developed a discussion guide containing a series of questions on the women’s experiences during their birth hospitalization, communication with providers, and if they perceived differential treatment for any reason. Women were not asked specifically about racial-ethnic discrimination so that reasons for any differential treatment could emerge from the women themselves. Examples of questions include: “Was there a doctor, nurse, or other health care provider during your time in the hospital with whom you felt uncomfortable asking questions? Tell me more about this experience.”; “Can you describe any time during your care you may have felt you were treated differently from other women? Why do you think you were treated differently?” Moderators were of a similar racial-ethnic background as study participants and were trained in the content of the discussion guide.

The Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai approved this study. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Two analysts coded transcripts for emergent themes, using the constant comparison method to reconcile and refine code structure. Coding was initially blind followed by open coding. Analysts shared findings and attained a consensus to label themes. Themes that were closely related were merged. Analysts categorized themes into existing conceptual framework domains through an iterative consensus process and added new domains when necessary. Coding and analysis were conducted in Dedoose.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the focus group participants are shown in Table 1. Most women were between the ages of 25-35 (63%) and obtained either a bachelor’s degree (33%) or high school diploma (30%). A range of parity was represented, with equal numbers of women having one, two, or three or more children. Most women were born in the United States (70%).

Table 1. Characteristics of focus group participants.

| Characteristic | Total, n=27 | Black, n=11 | Latina, n=16 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age, yrs. | |||

| < than 24 | 5 (19) | 3 (27) | 2 (13) |

| 25-34 | 17 (63) | 5 (45) | 12 (75) |

| 35-44 | 4 (15) | 3 (27) | 1 (6) |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| High school diploma | 8 (30) | 5 (45) | 3 (19) |

| Some college | 2 (7) | 1 (9) | 1 (6) |

| Associate’s degree | 5 (19) | 4 (36) | 1 (6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 9 (33) | 1 (9) | 8 (50) |

| Missing | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (13) |

| Number of children | |||

| 1 | 8 (30) | 4 (36) | 4 (25) |

| 2 | 8 (30) | 4 (36) | 4 (25) |

| 3 or more | 10 (37) | 3 (27) | 7 (44) |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Country of birth | |||

| United States | 19 (70) | 10 (91) | 9 (56) |

| Other | 7 (26) | 1 (9) | 6 (38) |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Years in the US (denominator is foreign-born women) | |||

| <10 years | 4 (57) | 1 (100) | 3 (50) |

| >10 years | 3 (43) | 0 | 3 (50) |

Domains and Themes

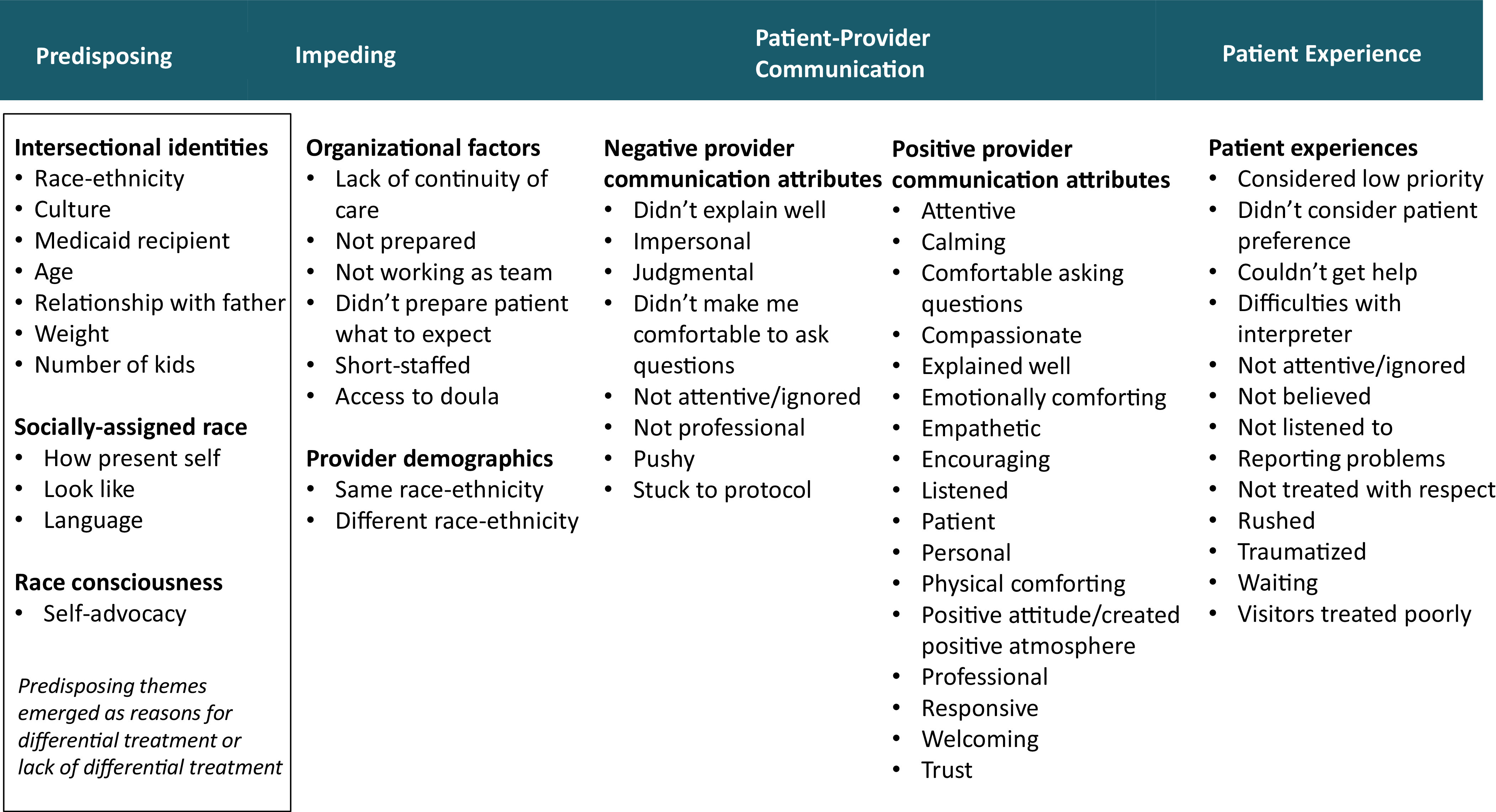

The conceptual model with emergent themes is displayed in Figure 1. CRT concepts were situated as starting predisposing domains: “Intersectional identities,” “Socially assigned race,” and “Race-consciousness.” Enabling/impeded domains that emerged during analysis were: “Organizational factors” and “Physician characteristics.” Communication outcome domains were divided into “Positive provider communication attributes” and “Negative provider communication attributes.” Patient experiences were grouped together under one domain.

Figure 1. Conceptual frameworka of perceived racial-ethnic discrimination in obstetric care and themes from focus groups of Black and Latina women.

a. Framework is adapted from the Behavioral Model of Vulnerable Populations using concepts from Critical Race Theory

The domain “Intersectional identities” contained themes of self-identified characteristics that women described as reasons for differential treatment. Sometimes women spoke specifically about being Black or Latina.

“I would ask myself whether it was because I was a Latina. If [the doctor would] ask that question to another person.”

Sometimes women discussed differential treatment not only because of their race-ethnicity but that of their husband’s as well.

“… as Latina, and with an Afro-American husband, the nurses came in with a preset mind about us. And that bothered me… I told [the nurse], you’re making me feel ashamed when you’re trying to help me. And I see how they treat someone else from another culture, and it’s not the same.”

The importance of the father in differential treatment came across also because of their relationship with their baby’s father. After one woman stated she felt treated differently because she wasn’t married to the father of her baby, a second woman agreed and described how she felt the nurse was being judgmental about their relationship:

“And when [my husband] came to see me, the nurse said [to him], oh, your daughter’s mom or your wife?”

Age was also a perceived reason for differential treatment, both young age and older age.

“[The nurses] were super dismissive. … Maybe I look younger than what I am and you’re looking at it as we’ll come back to you or whatever. At the end of the day, I’m a patient. I’m your patient and you’re supposed to put your patient first.”

“So when [the staff signing me in] asked me oh, you’re 30 and this is your first child? It’s like oh my God, you’re like kind of old. You should be knowing what’s going on at 30.”

Finally, women identified themselves by the type of insurance they had, for example, Medicaid. Insurance type was described as a reason women felt they were treated differently.

“I think that they shouldn’t let it be known to people [that it is an issue what type of insurance they have] because regardless of if it’s coming from my pocket or a private pocket, you’re still being paid for my stay, right?”

The domain “socially assigned race” included themes that described situations in which women felt providers were making assumptions about their race or ethnicity, which in turn played heavily into women’s perceptions of how they were treated. Emergent themes included how women presented themselves, what they looked like, and language spoken.

“I feel that sometimes [doctors treat you different because of] the way you look.”

“[The nurses would] speak Spanish to me. When I’d [answer] them in English, to them, it was like, oh, okay, and the tone of how they would tell me things would change.”

Women’s awareness of what it meant to be a woman of color came through in their discussions.

“I think as a woman of color, if I am not assertive, if I am not willing to ask, then they will not make an effort to answer. I have that constantly in my mind [and] I see [that] in my life just in general, the difference between behaviors of people that are White next to people that are of color.”

“I think if I wasn’t as assertive in asking questions of what’s occurring in the procedure, I think I wouldn’t have had - - the answers that I was seeking. If I would have stayed quiet, then I think [the doctor] just would have gone through the bullshit.”

We situated the domain “organizational factors” as impeding factors in the conceptual framework. This domain included themes in which women discussed organization-level factors involved in their care. Having a doula present at childbirth was expressed as something that bridged communication with the health care providers.

“I [had] a doula. Communication with the doctors [was] very protocol, like ‘Hey, this is what we’re going to do now.’ And then I would say, ‘I don’t want to do anything like that,’ so with the help of my doula then I was able to have that communication with the doctors.”

Several women expressed that continuity of care, ie, seeing the same doctor at delivery as they had during prenatal care, helped to establish trust.

“…it feels good to say, ‘Oh, I actually know somebody. I have a doctor.’ …I’m connected to you in some way and I trust you.

Provider demographics was another domain included as impeding factors. We asked women if they felt it was important if their provider was of the same race or ethnicity as themselves, although in some cases this arose prior to our question. Some women felt treated well by providers who were of the same racial or ethnic background.

“I think that it is important [that a doctor is of the same racial or ethnic background], not only because of the language, but I think that in my experience, a doctor from another race may have an idea about you because they see many different women. I am Latina, you are Latina, we are very different, but we are the same in a different way.

However, some women emphasized that differential treatment could happen from providers of the same race/ethnicity.

“I think because [the nurses] were African American, they weren’t as attentive to me, as I felt they were to other patients that were walking by and had a question.”

The domain “negative provider attributes” included examples of poor communication style of doctors, nurses, and staff. All negative communication themes co-occurred with differential treatment themes with the exception of “stuck to protocol.” One negative communication theme that stood out was “impersonal”:

“I felt like [the doctor] was trying to take control over my experience. I felt that she wasn’t really empathetic with what was going on.”

“… we are all humans and we are going through something life-changing, [a woman] needs to feel like she is wanted and that she’s valued.”

Some women felt like it was difficult to ask questions.

“Sometimes it is just easier to look it up or easier to ask my mom or somebody in my family - - [it] shouldn’t be that way. I feel like [the doctors] should communicate [what] was going on.”

The domain “positive communication attributes” included many themes that emerged as women discussed their experiences during delivery and postpartum. Women encountered many positive communication attributes that they valued, including emotionally comforting, calming, attentive, and explaining well.

“I think [my doctors] were still really concerned about my health so they were- they communicated with me. …I had thousands of questions … they took time to answer, and made me feel comfortable.”

Empathy and humanism arose numerous times when women expressed what they wanted from a provider.

“The other thing is empathy, like I said, instead of sympathy. I don’t want you to look down on me, I want you to look at me as what would I want if this was me.”

Positive communication attributes were associated with equal treatment.

“If you have humanity… if you’re aware of what’s happening to the person who was in labor who was going through this and you can relate and you can empathize, it really doesn’t matter what race you are.”

Patient Experiences

Negative experience themes included being considered a low priority, not being able to get help, being ignored, not listened to, not believed, not treated with respect, rushed, not having their preferences considered, being traumatized, and having their visitors treated poorly. For example, one woman described not being able to get help:

“If you call [nursing assistants] to help you, they don’t even, sometimes, listen to you. One day I … was thinking I’m going to die. I called the … nursing assistant …to come and help... I see in her face that she doesn’t even want to try to help me.”

Not being listened to, or even if listened to, not believed, and not treated with respect arose as negative patient experiences. In the following excerpt, all three themes arose in the same story:

“… I felt as if [the doctor] didn’t listen to me, what I was telling [him] about my body. [He] kept on telling me, but I can give you medicine for the pain, to calm down. I said, but I’m calmed. I don’t need medicine. And I think that the doctor that kept on seeing me, he didn’t have respect for my body.”

One woman who experienced both providers who did and didn’t listen well expressed,

“Just because you have ears doesn’t mean you can hear. You can tell when people are listening to what you’re sharing.”

Discussion

We found that Black and Latina women’s perceptions of differential treatment during childbirth were rooted in complex identities, race consciousness, and socially assigned race. Our findings build on recent qualitative research that has unearthed themes describing perceived racial-ethnic discrimination during obstetric care, eg, disrespect, in which women described being dismissed and treated rudely because of their race.15,16 Researchers have also theorized how interactions with health care providers influence the ability of women of color to control their pregnancy and childbirth experiences.16 We add to this literature by placing themes of differential treatment within a framework of CRT and by providing rich description of communication and experience outcomes.

Analysis of our focus group discussions from the point of intersectional identities brought to light new findings, one of which is the central role the father of the baby plays in a woman’s own identity. Fathers arose in discussions both as a subject of bias (eg, women perceived being judged due to their relationship status), and also as a receipt of bias (eg, several women perceived their partners or family were treated differently by providers or staff than those of other women). Research has found that a father’s satisfaction during childbirth is correlated with the mother’s satisfaction, and the needs of fathers are not always being met.26 To date, little attention has been paid as to their role in provider bias and perceived racial-ethnic discrimination. Our study demonstrates that the father of the baby is interwoven in the mother’s identity, whether or not he is present, and interventions to improve the care of women of color and/or reduce bias should consider the role of the father.

We found qualitative evidence that women felt the racial or ethnic identity assigned by providers influenced their treatment of women. This evidence is in line with previous research that found that socially assigned identity had a greater association with health care discrimination than did self-identity.27 In our study, sometimes women expressed they did not experience any differential treatment, but at the same time attributed it to the fact that as a woman of color they knew they needed to act or present themselves a certain way. This hypervigilance to racial microaggression has been identified as a factor impacting the delivery of patient-centered care,28 and could be present as a stressor influencing health care communication and experience, either in parallel with or independent of perceived provider bias.

We identified impeding factors that could be points of intervention to buffer perceptions of differential treatment, for example, access to a doula. Women with a doula present described improved communication and ability to control their childbirth experience. Doula care has long been discussed as a potential way to improve quality of care, in particular for patients facing social disadvantages.29 Other organization of care factors such as continuity of care bolstered women’s trust. Women expressed how seeing the same midwife or obstetrician at delivery who provided their care during pregnancy improved communication and experience. This is supported by the literature; continuity of obstetric care has been associated with perceived quality of care.30 These findings suggest that overall improvement of organization of care may reduce the opportunity for differential treatment, and improve perceptions of fairness and trust.

In addition to organization of care, the race-ethnicity of the provider was an impeding factor, but not always how we expected based on previous literature.31 Although some women expressed being able to communicate better with providers of a similar racial or ethnic background, others felt it was providers with similar background, either Black or Latina, who treated them poorly due to their race-ethnicity. Caution should therefore be made to not make assumptions regarding the impact of provider-patient racial-ethnic concordance on women’s perceptions of racial-ethnic discrimination.

Positive provider communication attributes in our focus group discussion appeared to be associated with lack of differential treatment, or possibly to buffer it. This idea supports Hardeman et al’s proposition that relationship-centered care, in which all participants appreciate the importance of their relationships with each other, with an emphasis on emotional support and empathy, may be an antidote to structural racism.21 Empathy and other communication qualities emerging in our focus groups are in line with previous research on patient-reported outcomes associated with satisfaction during the delivery hospitalization.32 However, it is unclear if improving quality of care along these dimensions will reduce perceived differential treatment independent of specific interventions tackling provider bias.

Our findings have implications for the measurement of perceived racial-ethnic discrimination in obstetric care. Women were sometimes reluctant to attribute perceived differential treatment to race-ethnicity, but instead attributed it to another factor. Therefore, a two-step attribution process in which women are first asked if they were treated differently and then asked why, would likely be more sensitive to provider bias. Also, questions on socially assigned race and race consciousness should accompany assessment of perceived racial-ethnic discrimination, as these may modify any association with health care outcomes.

Our study also has implications for patient experience metrics, and motivates the question if perceived discrimination should be a domain of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS®).33 A goal of HCAHPS is to measure quality of care from the patient perspective, and HCAHPS surveys serve as quality improvement metrics and are part of CMS reimbursement. Currently perceived health care discrimination is not included, and further research is needed to understand if doing so would improve the assessment of equitable care beyond existing measures.

Study Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Our study sample consisted of urban Black and Latina women, and may not be generalizable to other populations. Our sample also did not include women with private insurance. However, 69% of Black and 78% of Latina women delivering in NYC are insured by Medicaid or other public insurance.34 Also, women who agree to participate in a focus group discussion may not represent all birthing people. Future quantitative research based on a random sample is needed to improve generalizability and to rigorously test hypotheses of the influence of perceived differential treatment on maternal health outcomes. We also acknowledge the limitation of our application of CRT concepts to study perceived racial-ethnic discrimination. Central to CRT is the idea that racism is structural and pervasive and not limited to individual acts; yet, by asking women about differential treatment, our focus group discussions shifted to perceptions of individuals and experiences.

Conclusion

Perceived racial-ethnic discrimination during childbirth influenced patient-provider communication. Differential treatment was attributed to complex identities, and race consciousness and socially assigned race shaped women’s experiences. Organization of care and positive communication practices may serve to mitigate or prevent perceived racial-ethnic discrimination. Interventions to reduce obstetric health care disparities should address perceived health care discrimination, both from the provider and patient perspectives.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Hospitals Insurance Company and the Blavatnik Family Foundation for funding this study.

References

- 1.Callaghan WM. Maternal mortality: addressing disparities and measuring what we value. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(2):274-275. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003678 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):143-152. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Severe maternal morbidity among Hispanic women in New York City: investigation of health disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(2):285-294. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, et al. Race and ethnicity, medical insurance, and within-hospital severe maternal morbidity disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(2):285-293. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335-343. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janevic T, Egorova NN, Zeitlin J, Balbierz A, Hebert PL, Howell EA. Examining trends in obstetric quality measures for monitoring health care disparities. Med Care. 2018;56(6):470-476. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson JD, Asiodu IV, McKenzie CP, et al. Racial and ethnic inequities in postpartum pain evaluation and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(6):1155-1162. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant A, Blake-Lamb T, Hatoum I, Kotelchuck M. The postpartum visit: predictors, disparities and opportunities. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:74S-75S. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/01. AOG.0000483710.53534.56 [DOI]

- 9.Jain JA, Temming LA, D’Alton ME, et al. SMFM Special Report: Putting the “M” back in MFM: Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: A call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):B9-B17. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain J, Moroz L. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(5):323-328. 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paradies Y, Truong M, Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):364-387. 10.1007/s11606-013-2583-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, et al. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953-966. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black LL, Johnson R, VanHoose L. The relationship between perceived racism/discrimination and health among black American women: A review of the literature from 2003 to 2013. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(1):11-20. 10.1007/s40615-014-0043-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Patient-reported communication quality and perceived discrimination in maternity care. Med Care. 2015;53(10):863-871. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper N, Williams S, Rand L, Franck L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. 2018;201:127-135. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman MR, Oseguera T, McLemore MR, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Franck LS, Lyndon A. Information and power: women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Soc Sci Med. 2019;238:112491. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgado R, Stefancic J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical Race Theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1)(suppl 1):S30-S35. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390-1398. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham L, Brown-Jeffy S, Aronson R, Stephens C. Critical race theory as theoretical framework and analysis tool for population health research. Crit Public Health. 2011;21(1):81-93. 10.1080/09581596.2010.493173 10.1080/09581596.2010.493173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardeman RR, Karbeah J, Kozhimannil KB. Applying a critical race lens to relationship-centered care in pregnancy and childbirth: an antidote to structural racism. Birth. 2020;47(1):3-7. 10.1111/birt.12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality-an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267-1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):1079-1092. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200-208. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CP, Truman BI, Elam-Evans LD, et al. Using “socially assigned race” to probe white advantages in health status. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):496-504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howarth AM, Scott KM, Swain NR. First-time fathers’ perception of their childbirth experiences. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(7):929-940. 10.1177/1359105316687628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepanikova I, Oates GR. Dimensions of racial identity and perceived discrimination in health care. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(4):501-512. 10.18865/ed.26.4.501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman L, Stewart H. Microaggressions in clinical medicine. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2018;28(4):411-449. 10.1353/ken.2018.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozhimannil KB, Vogelsang CA, Hardeman RR, Prasad S. Disrupting the pathways of social determinants of health: doula support during pregnancy and childbirth. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(3):308-317. 10.3122/jabfm.2016.03.150300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perdok H, Verhoeven CJ, van Dillen J, et al. Continuity of care is an important and distinct aspect of childbirth experience: findings of a survey evaluating experienced continuity of care, experienced quality of care and women’s perception of labor. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):13. 10.1186/s12884-017-1615-y 10.1186/s12884-017-1615-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornton RLJ, Powe NR, Roter D, Cooper LA. Patient-physician social concordance, medical visit communication and patients’ perceptions of health care quality. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e201-e208. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregory KD, Korst LM, Saeb S, et al. Childbirth-specific patient-reported outcomes as predictors of hospital satisfaction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(2):201.e1-201.e19. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein E, Farquhar M, Crofton C, Darby C, Garfinkel S. Measuring hospital care from the patients’ perspective: an overview of the CAHPS Hospital Survey development process. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 2):1977-1995. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00477.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Summary of Vital Statistics 2018 City of New York. New York: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; 2019. [Google Scholar]