ABSTRACT

Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is produced by granulosa cells of pre-antral and small antral ovarian follicles. In polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), higher levels of serum AMH are usually encountered due to the ample presence of small antral follicles and a high AMH production per follicular unit which have led to the proposal of AMH as a serum diagnostic marker for PCOS or as a surrogate for polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM). However, heterozygous coding mutations of the AMH gene with decreased in vitro bioactivity have been described in some women with PCOS. Such mutation carriers have a trend toward reduced serum AMH levels compared to noncarriers, although both types of women with PCOS have similar circulating gonadotropin and testosterone (T) levels. This report describes a normal-weight woman with PCOS by NIH criteria with severely reduced AMH levels (index woman with PCOS). Our objective was to examine the molecular basis for her reduced serum AMH levels and to compare her endocrine characteristics to similar-weight women with PCOS and detectable AMH levels. Twenty normoandrogenic ovulatory (control) and 13 age- and BMI-matched women with PCOS (19–35 years; 19–25 kg/m2) underwent transvaginal sonography and serum hormone measures including gonadotropins, sex hormone-binding globulin, total and free T, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, estrone, estradiol and AMH. The latter was measured by ELISA (Pico-AMH: Ansh Labs, Webster, TX, USA). Women with PCOS and detectable AMH had higher serum AMH (10.82 (6.74–13.40) ng/ml, median (interquartile range)), total and free T (total T: 55.5 (49.5–62.5) ng/dl; free T: 5.65 (4.75–6.6) pg/ml) levels and greater total antral follicle count (AFC) (46 (39–59) follicles) than controls (AMH: 4.03 (2.47–6.11) ng/ml; total T: 30 (24.5–34.5) ng/dl; free T: 2.2 (1.8–2.45) pg/ml; AFC 16 (14.5–21.5) follicles, P < 0.05, all values), along with a trend toward LH hypersecretion (P = 0.06). The index woman with PCOS had severely reduced serum AMH levels (∼0.1 ng/ml), although she also had a typical NIH-defined PCOS phenotype resembling that of the other women with PCOS and elevated AMH levels. All women with PCOS, including the index woman with PCOS, exhibited LH hypersecretion, hyperandrogenism, reduced serum estrogen/androgen ratios and PCOM. A homozygous Ala515Val variant (rs10417628) in the mature region of AMH was identified in the index woman with PCOS. Recombinant hAMH-515Val displayed normal processing and bioactivity, yet had severely reduced immunoactivity when measured by the commercial pico-AMH ELISA assay by Ansh Labs. In conclusion, homozygous AMH variant rs10417628 may severely impair serum AMH immunoactivity without affecting its bioactivity or PCOS phenotypic expression. Variants in AMH can interfere with serum AMH immunoactivity without affecting the phenotype in PCOS. This observation can be accompanied by discordance between AMH immunoactivity and bioactivity.

Keywords: anti-Müllerian hormone, gene mutations, variants, polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperandrogenism

Introduction

As a homodimeric glycoprotein of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) is produced by granulosa cells of pre-antral and small antral ovarian follicles. Binding of AMH to the AMH-specific type 2 receptor (AMHR2) initiates the AMH signaling pathway by activating a serine/threonine kinase receptor complex with type 2 (i.e. AMHR2) and type 1 (i.e. activin receptor-like kinase) components, which then phosphorylates the downstream SMAD proteins (Cate et al., 1986; Gouedard et al., 2000; di Clemente et al., 2003, 2010; Shi and Massague, 2003; Broekmans et al., 2008; Pierre et al., 2016). For this to occur, AMH is initially translated as an inactive homodimeric precursor that contains a N-terminal pro-region and a smaller C-terminal mature domain (Pierre et al., 2016). The homodimeric precursor (covalent form) undergoes obligatory cleavage between its pro-region and mature domain but remains associated (noncovalent form) until it binds to AMHR2 to initiate intracellular signaling (di Clemente et al., 2010; Pierre et al., 2016).

Within the ovary, AMH inhibits primordial follicle recruitment and impairs both FSH-stimulated small antral follicle development and aromatase activity (Vigier et al., 1989; di Clemente et al., 1992; Andersen and Byskov, 2006; Broekmans et al., 2008; Catteau-Jonard and Dewailly, 2013). AMH in mice also inhibits Leydig cell androgen synthesis, suggesting that AMH in women could inhibit ovarian theca cell androgen synthesis through transcriptional CYP17A1 repression (Teixeira et al., 1999, 2001).

Theoretically, therefore, such an inhibitory paracrine interaction of granulosa cell AMH on theca cell androgen synthesis could have important implications for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the most common endocrinopathy of reproductive-aged women characterized by ovarian hyperandrogenism, oligo-anovulation and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) (Dumesic et al., 2015). Normally, serum AMH levels in women with PCOS are increased above normal values due to exaggerated numbers of small antral follicles that overexpress AMH per granulosa cell (Pigny et al., 2003; Pellatt et al., 2007). However, serum AMH levels are not currently recommended as an alternative for detecting PCOM or as a single test for diagnosing PCOS until there is improved standardization of assays and established cutoff levels based upon large scale validation (Teede et al., 2018, 2019). Moreover, PCOS-specific AMH- and AMHR2-related genetic mutations have been identified in approximately 7% of a cohort of over 600 women with PCOS, of which 3% involved heterozygous coding mutations of the AMH gene associated with reduced in vitro bioactivity (Gorsic et al., 2017, 2019). Within this cohort, carriers of some of these PCOS-specific AMH mutations versus noncarriers also had a trend toward reduced serum AMH levels, but without exaggerated LH hypersecretion or hyperandrogenemia (Gorsic et al., 2017, 2019). Furthermore, undetectable serum AMH levels have been reported in another woman with PCOS, menstrual irregularity and hyperandrogenemia, although further details of her clinical manifestations are unclear (Grbavac et al., 2018).

We recently identified severely reduced serum AMH levels in a normal-weight woman with PCOS by NIH criteria. This report examines the molecular basis for reduced serum AMH levels and its relationship to clinical and biochemical manifestations in this individual relative to a cohort of other normal-weight women with NIH-defined PCOS and elevated serum AMH levels, as defined by age- and BMI-matched normoandrogenic ovulatory women.

Case report

Case description

A 27-year-old G1P1001 normal-weight White woman with PCOS was enrolled in our NIH-funded study (P50 HD071836) regarding endocrine-metabolic dysfunction in PCOS (Dumesic et al., 2016). She had menstrual irregularity, hyperandrogenemia and PCOM, with ≥20 small antral follicle count (AFC) per ovary. Her past medical history was unremarkable except for attention deficit disorder. She had one Cesarean section at term without complications and gave up the neonate for adoption. She was allergic to amoxicillin and occasionally used alcohol and tobacco cigarettes. Her family history was unknown because she was adopted. Physical exam was unremarkable. Her serum hormone measures are depicted in Table I, along with her severely reduced serum AMH levels (∼0.1 ng/ml).

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of normal-weight controls, women with PCOS and an index woman with PCOS and severely reduced serum AMH levels.

| Controls median* (quartiles) | PCOS median* (quartiles) | P-value | Index PCOS woman (Rank/14)** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCOS cohort vs controls | ||||

| Patient characteristics | n = 21 | n = 13 | n = 1 | |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 4.03 (2.47–6.11) | 10.82 (6.74–13.40) | <0.001 | 0.10 (1) |

| E2/Total T | 2 (1.05–3.83) | 1.04 (0.92–1.16) | 0.006 | 0.85 (4) |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 5.3 (4.6–7) | 5.70 (4.80–5.90) | 0.834 | 5.60 (5) |

| AFC | 16 (14.5–21.5) | 46 (39–59) | <0.001 | 43 (6) |

| DHEAS (µg/dl) | 165 (116–202) | 217 (197–272) | 0.018 | 239 (9) |

| E1/A4 | 0.46 (0.37–0.77) | 0.35 (0.30–0.41) | 0.055 | 0.38 (9) |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 71 (47–81) | 47 (34–61) | 0.12 | 60 (10) |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 60 (34–97) | 56 (41–67) | 0.675 | 76 (11) |

| Free T (pg/ml) | 2.2 (1.8–2.45) | 5.65 (4.75–6.60) | <0.001 | 7 (11) |

| Total T (ng/dl) | 30 (24.5–34.5) | 55.5 (49.5–62.5) | <0.001 | 89 (12) |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 7.8 (5.7–10.5) | 13.3 (6.8–14.7) | 0.055 | 23.9 (13) |

| A4 (ng/dl) | 111 (90–142) | 191 (134–230) | 0.004 | 380 (14) |

| E1 (pg/ml) | 58 (44–80) | 59 (53–73) | 0.506 | 145 (14) |

Median compared between groups using the Wilcoxon test.

Patient characteristics are sorted by rank of the PCOS index woman within the PCOS cohort.

A4, androstenedione; AFC, antral follicle count; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; E1, estrone; E2, estradiol; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; T, testosterone.

Conversion to SI units: T (×0.0347 nmol/l), free T (×3.47 pmol/l), A4 (×0.0349 nmol/l), DHEAS (×0.0271 µmol/l), E1 (×3.699 pmol/l), E2 (×3.67 pmol/l), LH (×1.0 IU/l), FSH (×1.0 IU/l).

Study participants

Approval by the UCLA Institutional Review Board was obtained. Thirteen normal-weight women with PCOS (in addition to the index woman with PCOS) and 21 normoandrogenic ovulatory (control) women (19–35 years; 19–25 kg/m2) who participated in the NIH study noted above also were studied (Dumesic et al., 2016). Control women had normal menstrual cycles at 21- to 35-day intervals and a luteal phase progesterone (P4) level without hirsutism, acne or alopecia, while women with PCOS were diagnosed by 1990 NIH criteria as previously described (Dumesic et al., 2015, 2016).

Antral follicle count

Transvaginal ultrasound ovarian imaging using a 4- to 8-mHz vaginal probe was performed in the early follicular phase in control women or during a period of amenorrhea in all women with PCOS. The total AFC (2–9 mm in diameter) of each ovary was determined by one investigator (D.A.D).

Blood sampling

Blood sampling was performed in the follicular phase in control women or during documented oligo-anovulation by serum P4 levels in women with PCOS. Fasting blood samples were collected to measure AMH, LH, FSH, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), total and free testosterone (T), androstenedione (A4), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2).

Hormone and metabolite assay

Serum levels of DHEAS, A4, total T and E1 were measured by LC-MS/MS (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 5.4% and 5.5% for DHEAS, 3.8% and 5.2% for A4, 10.7% and 9.5% for total T and 3% and 14.7% for E1. Free T was calculated from the concentrations of total T, SHBG and albumin. The intra- and inter-assay CVs for free T were 5.0% and 7.8%, respectively.

Serum determinations of LH, FSH and E2 were done by electrochemiluminescence and performed at the UCLA Center for Pathology Research Services. The intra- and inter-assay CVs were 2.8% and 2.6% for LH, 2.8% and 2.6% for FSH and 7% and 3.6% for E2, respectively.

AMH assays

Serum AMH levels were measured by ELISA (Ansh Labs, Webster, TX, USA) in the Endocrine Technologies Core (ETC) at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) following manufacturer’s instructions. The assay range was 0.084–14.2 ng/ml with a limit of detection of 0.023 ng/ml. Ansh Labs supplies two controls with the kit, Control I and Control II. For Control I, intra-assay CVs ranged from 2.1% to 8.8% and the inter-assay CV was 8.2%. For Control II, intra-assay CVs ranged from 1.2% to 6.1% and the inter-assay CV was 11.9%. Using an in-house nonhuman primate serum quality control pool with each assay, the intra-assay CVs ranged from 0.9% to 7.6%, and the inter-assay CV for this pool was 11.6%.

Molecular analysis

From the index woman with PCOS and the 10 normal-weight women with PCOS and detectable AMH, DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leucocytes using Magnetic Separation Module 1 from Chemagen (Baesweiler, Germany). Polymerase chain reaction amplification and direct sequencing of the AMH gene (all 5 exons with flanking sequences) was performed as described previously (van der Zwan et al., 2012). The Human Genome Variant Society (HGVS) nomenclature was applied for nucleotide numbering (http://www.hgvs.org/varnomen) (den Dunnen et al., 2016). Due to the reported 3% prevalence of heterozygous AMH variants in women with PCOS (Gorsic et al., 2017, 2019), we did not genotype the other study subjects since the probability of detecting an AMH variant among the small number of remaining subjects was less than 1%.

Production of recombinant human AMH (hAMH)

To introduce the variant into the pcDNA3.1-hAMH expression vector, quick-change site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to the protocol of Stratagene. Expression plasmids without (RAQR) or with an optimized cleavage site (RARR) were used. HEK293 cells were transfected with the hAMH-515Ala and hAMH-515Val expression plasmids. Cell lysates and supernatants were collected from transiently or stably transfected cells as described previously (Kevenaar et al., 2008). Recombinant human AMH samples were measured by the pico-AMH ELISA assay (Ansh Labs, Webster, TX, USA) (supernatants and cell lysates) and by an automated AMH assay (Fujirebio Lumipulse G1200, Fujirebio Europe) (supernatants only).

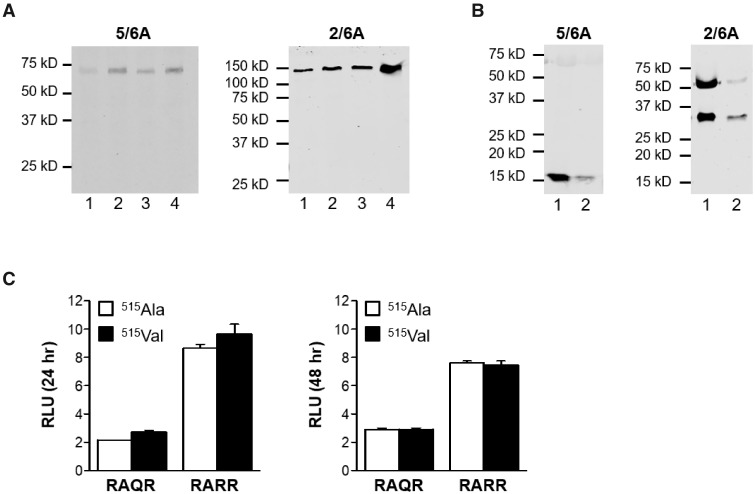

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis and visualization of the AMH protein was performed as described previously (Kevenaar et al., 2008). The mouse monoclonal antibodies 5/6A (recognizing the C-terminal mature region) and 2/6A (recognizing the N-terminal pro-region) were used as primary antibodies, and the Alexa Fluor-800 goat anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands) served as a secondary antibody (Kevenaar et al., 2008).

Cell transfections

The mouse granulosa cell line KK-1 (Kananen et al., 1995), stably transfected with an AMHR2 expression plasmid, was used to analyze AMH-induced luciferase activity as described previously with slight modifications (Kevenaar et al., 2008). In brief, KK-1 cells, cultured in DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies, Inc., Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands) with 10% v/v fetal calf serum, were seeded at 70% confluency in a T25 culture flask and transfected with the BRE-Luc reporter plasmid (2 µg) (Korchynskyi and ten Dijke, 2002), the pRL-SV40 plasmid (1 µg) (internal control for transfection efficiency), together with the hAMH-515Ala or hAMH-515Val expression plasmids (1 µg) using Fugene HD transfection reagent (Promega, Benelux, Leiden, The Netherlands). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were seeded into 24-well plates. Next, cells were cultured in 0.2% fetal calf serum containing medium for 24 or 48 h, followed by luciferase activity measurement using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay (Promega, Benelux, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

A Wilcoxon rank-sum test compared the clinical characteristics of women with PCOS and controls, excluding the index woman with PCOS and reduced serum AMH levels. The same clinical characteristics of the index woman with PCOS and reduced serum AMH levels were then individually ranked in order of magnitude relative to the other women with PCOS. Differences in in vitro responses between the two AMH variants were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with P < 0.05 being considered statistically significant (GraphPad Prism, Version 5, GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics

As expected, serum AMH levels in the cohort of normal-weight women with PCOS were significantly elevated compared to serum AMH levels in control women. The same women with PCOS had significantly higher circulating total and free T, A4 and DHEAS levels accompanying a trend toward LH hypersecretion and also had significantly greater total ovarian AFC than control women (Table I). Serum FSH, E2 and E1 levels were similar in both female groups; serum E2 to T and E1 to A4 ratios were lower in these women with PCOS than controls. Serum SHBG levels also tended to be reduced in these women with PCOS compared to controls (Table I).

The index woman with PCOS and reduced serum AMH levels had similar circulating total and free T levels, and total ovarian AFC compared to the above cohort of women with PCOS and elevated serum AMH levels. She had the highest serum A4 and E1 levels and the second to highest serum LH level of all studied women with PCOS. However, compared to the other women with PCOS and elevated serum AMH, the index woman with PCOS and reduced serum AMH levels had similar serum FSH, E2, DHEAS and SHBG levels as well as comparable serum E2 to T and E1 to A4 ratios.

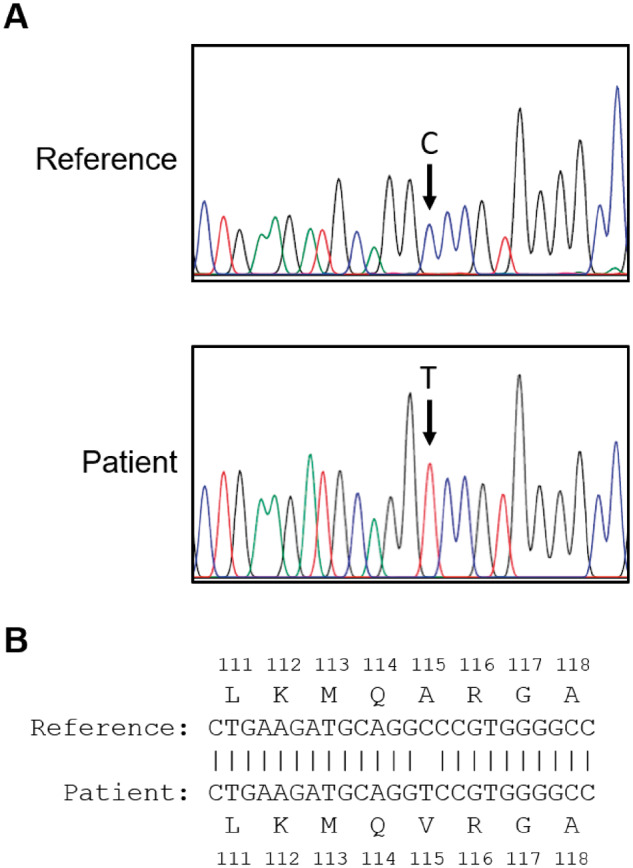

Sequence analysis

Based on the severely reduced AMH levels in the index woman with PCOS, a variant in the AMH gene was suspected. Upon direct gene sequencing of this woman with PCOS and 10 normal-weight women with PCOS and elevated AMH, a homozygous single base pair substitution was identified in exon 5 (NG_012190.1:g.7705C>T, p.(Ala515Val)) of the index woman with PCOS (Fig. 1A and B). No AMH variants were identified in the studied normal-weight women with PCOS and elevated AMH. This identified variant rs10417628 from the index woman with PCOS and reduced serum AMH levels had a reported minor allele frequency of 0.01–0.02 in European populations (Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP). Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information).

Figure 1.

DNA sequence analysis. (A) Sequence chromatograms of AMH of the woman with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and severely reduced serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and a control woman with PCOS. The arrow indicates the location of the mutation. (B) Nucleotide sequence alignment with predicted amino acid sequence corresponding to position g.7705 and flanking sequences.

Functional analysis

To determine the functional impact of p.(Ala515Val), the variant was introduced into an hAMH expression plasmid containing either the original (wild type) (RAQR) or optimized cleavage site (RARR), which allows for efficient cleavage of AMH as described previously (Nachtigal and Ingraham, 1996). Analysis of the hAMH content in cell lysates and supernatants of cells stably transfected with these expression plasmids by pico-AMH ELISA revealed that hAMH-515Val was undetectable in cell lysates, while only very low levels were detected in the supernatants of hAMH-515Val compared to hAMH-515Ala expressing cells. These results were independent of the presence of the optimized cleavage site (Table II). Supernatants of hAMH-RARR yielded a higher AMH content compared to hAMH-RAQR expressing cells, which is in line with the presence of the optimized cleavage site (Table II). Surprisingly, Western blot analysis did not reveal any difference in AMH processing. In cell lysates, both hAMH-515Ala and hAMH-515Val were detected as a monomeric precursor protein of 75 kD using the mature region-specific antibody and as a dimeric precursor of 150 kD using the pro-region-specific antibody (Fig. 2A). In supernatants, AMH could only be detected in hAMH-RARR expressing cells (Fig. 2B), reflecting the improved cleavage of AMH with an optimized cleavage site. Both hAMH-RARR-515Ala and hAMH-RARR-515Val were fully cleaved as indicated by the detection of the C-terminal mature region, and the N-terminal pro-region together with an additional band as a result of the potential second cleavage site in the pro-region (Fig. 2B). To detect AMH in the supernatant, we used a pool of stably transfected cells, which explains the differences in intensities.

Table II.

Effect of Ala515Val mutation on AMH production.

| hAMH-RAQR-515Ala | hAMH-RAQR-515Val | hAMH-RARR-515Ala | hAMH-RARR-515Val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lysate* (ng/ml) | 62.68 | Non-detected | 1027.12 | Non-detected |

| Supernatant* (ng/ml) | 8486.5 | 83.08 | 91361.95 | 122.41 |

| Supernatant# (ng/ml) | 94.6 | 181.7 | 2431.7 | 182.8 |

AMH was measured in cell lysates and supernatants of HEK293 cells stably transfected with hAMH-515Ala or hAMH-515Val expression constructs without (RAQR) or with (RARR) the optimized cleavage site using the picoAMH assay (Ansh Labs), indicated by*, or the automated Lumipulse G1200 (Fujirebio), indicated by #.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis and bioactivity of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) proteins AMH-515Ala and AMH-515Val. Western analysis of HEK293 cells expressing the hAMH variants without (RAQR) or with (RARR) the optimized cleavage site were analyzed. The mature region-specific 5/6A antibody recognizes the AMH precursor protein (75 kD) and the cleaved C-terminal mature protein (∼15 kD). The pro-region-specific 2/6A antibody recognizes the dimeric AMH precursor protein (150 kD) and the cleaved N-terminal pro-region (∼57 kD). The relative molecular masses (kD) of the protein marker are indicated on the left. No difference was observed in processing of the AMH variants. Cell lysates (A) Lane 1: hAMH-RAQR-515Ala; lane 2: hAMH-RAQR-515Val; lane 3: hAMH-RARR-515Ala; lane 4: hAMH-RARR-515Val. Supernatants (B) Lane 1: hAMH-RARR-515Ala; lane 2: hAMH-RARR-515Val. (C) Analysis of AMH-515Ala and AMH-515Val bioactivity. KK1/AMHR2 cells were transiently transfected with the AMH-responsive BRE-Luc reporter plasmid together with the hAMH variants without (RAQR) or with (RARR) the optimized cleavage site. Luciferase was measured after 24 and 48 h incubation. No differences were observed in luciferase stimulation by both variants. Data are presented as relative luciferase units (RLU) expressed relative to the empty vector control. Data points are the mean ± SEM of triplicates of a representative experiment, which was repeated at least three times.

Since Western blot analysis suggested that the hAMH-515Val protein was produced, we next determined the effect of this variant on the bioactivity of AMH. Co-transfection of the hAMH expression plasmids with the AMH-responsive BRE-Luc reporter showed that the bioactivity of recombinant hAMH-515Val did not differ from recombinant hAMH-515Ala (Fig. 2C). Transfection of different concentrations of the expression plasmids did not affect the results (data not shown) nor the duration of stimulation (Fig. 2C). Transfection with hAMH-RARR plasmids resulted in a stronger luciferase response due to increased production of cleaved AMH.

Since hAMH-515Val protein was produced and had a similar bioactivity as hAMH-515Ala, but was undetected by ELISAs from Ansh Labs, we questioned whether the immunoactivity of the 515Val variant of AMH was affected. Therefore, we next measured AMH content in an independent batch of supernatants using an AMH assay from a different manufacturer, the automated Fujirebio Lumipulse G1200, which uses different antibodies (Table II). Using this assay, both the hAMH-RAQR variants were detected at nearly comparable levels. The difference in values for the hAMH-RARR variants is explained by supernatants obtained from a stable cell line (hAMH-RARR-515Ala) vs. transiently transfect cells (hAMH-RARR-515Val protein).

Discussion

This is the first report to our knowledge of a normal-weight woman with PCOS who was homozygous for the AMH rs10417628 variant and had severely reduced serum AMH levels that coexisted with a PCOS phenotype typical of other age- and BMI-matched women with PCOS. A missense variant in exon 5 of the AMH gene involving the mature domain of the AMH protein impaired serum AMH detection by a commercial picoAMH ELISA assay. Recombinant AMH, into which this variant was introduced, also was undetected in the picoAMH ELISA but was recognized using a different AMH ELISA and showed normal AMH bioactivity in vitro, which explains why this PCOS variant carrier had a PCOS phenotype similar to that of the other women with PCOS.

Eighteen heterozygous PCOS-specific AMH coding mutations have previously been identified, 17 of which have shown both reduced function in vitro by luciferase assay and impaired CYP17 transcription inhibition in mouse Leydig MA-10 cells (Gorsic et al., 2017). Of these 17 AMH coding mutations, one occurred in the mature region and sixteen occurred in the pro-region, likely affecting protein processing and/or bioactivity. In addition to AMH per se, several other loss-of-function mutations of the AMH signaling cascade also have been implicated in the etiology of PCOS (Gorsic et al., 2019), including three noncoding mutations upstream of AMH, one missense mutation in AMHR2 and 16 noncoding/splicing mutations involving AMHR2 (Gorsic et al., 2019). Such loss-of-function AMH-related mutations, could theoretically exaggerate hyperandrogenism in PCOS mutation carriers versus PCOS noncarriers (Rouiller-Fabre et al., 1998; Teixeira et al., 1999, 2001; Trbovich et al., 2001; Laurich et al., 2002; Gorsic et al., 2017; Kano et al., 2017), agreeing with findings in sheep that AMH knockdown by active immunization markedly increases ovarian follicle A4 levels (Campbell et al., 2012).

Several lines of clinical evidence, however, support sufficient circulating bioactive AMH in this index woman with PCOS and homozygous AMH variant rs10417628 to successfully inhibit CYP17A1 expression, suppress FSH-stimulated aromatase activity and block early ovarian folliculogenesis. First, serum T and free T levels were not exaggerated in the index woman with PCOS versus similar-weight women with PCOS and detectable AMH, consistent with similar findings among women with PCOS with and without coding heterozygous AMH mutations (Gorsic et al., 2017). Second, LH hypersecretion appeared similar between the index woman with PCOS and the other women with PCOS, suggesting that androgen inhibition of steroid negative feedback on LH and/or hypothalamic AMH action on LH are intact within the entire PCOS cohort (McCartney et al., 2002; Tata et al., 2018). Third, total ovarian AFC in the index woman with PCOS was similar to those of the other women with PCOS, implying comparable AMH inhibition of FSH-stimulated small antral follicle development; this contrasts with complete loss of AMH function in animal models whereby exacerbated ovarian follicular recruitment accompanies increased numbers of small antral follicles (Durlinger et al., 1999; Campbell et al., 2012). Finally, although serum levels of aromatizable A4 and its product E1 were highest in the index woman with PCOS, perhaps from enhanced adrenal responsiveness to adrenocorticotrophic hormone or other factors, comparable serum E2 levels and serum estrogen to androgen ratios in the index woman with PCOS versus the other women with PCOS implies similar AMH inhibition of CYP17A1 and aromatase activities among the entire PCOS cohort (Vigier et al., 1989; di Clemente et al., 1992; Chang and Dumesic, 2018).

The homozygous AMH variant rs10417628 in our index woman with PCOS, along with its recombinant mutant AMH protein, may have impaired antibody-epitope recognition of AMH by a commercial picoAMH ELISA assay, thereby severely reducing serum AMH immunoactivity without significantly altering its bioactivity. Epitopes for the antibodies used in the picoAMH ELISA assay by Ansh and the Gen II assay (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) have been studied by linear peptide screen (Robertson et al., 2014). In the Ansh lab assay, the capture antibody (Ab24) maps to epitope region 358–369, which is in the N-terminal region. The detector antibody (Ab32) yields strongest binding to epitope region 491–502, which is in the C-terminal region of the mature region of AMH. In this regard, the AMH mutation in our index woman with PCOS, previously unseen in over 600 women with PCOS (Gorsic et al., 2017, 2019), was identified at position 515 and close to the epitope of the detector antibody of the Ansh assay.

In contrast, the specific epitopes of the antibody pair used in the Gen II assay are not exactly known. However, they do not map to linear peptide sequences (Robertson et al., 2014), suggesting that these antibodies recognize conformational epitopes in AMH, emphasizing the three-dimensional structure of AMH as an important element of its immunoactivity. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the antibodies of the commercial picoAMH ELISA assay also were affected by additional conformational epitopes.

The discrepancy between AMH immunoactivity in vivo and bioactivity in vitro raises concern regarding the accuracy of serum AMH immunoactivity as a reliable marker of AMH bioactivity. In further support of this concern, previous reports have shown detectable serum AMH levels in PCOS carriers of heterozygous dominant-negative AMH mutations with impaired AMH bioactivity in vitro (Gorsic et al., 2019), and in boys with homozygous AMH mutations and persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (Josso et al., 2013). Fortunately, the prevalence of such PCOS-related heterozygous AMH variants is low (Gorsic et al., 2017, 2019), while homozygous AMH variants are even more unusual.

In conclusion, a homozygous AMH variant rs10417628 in a woman with a classical PCOS phenotype can severely impair serum AMH immunoactivity without affecting AMH bioactivity in vitro. We recommend that when undetectable or severely reduced serum AMH levels are found in a patient with PCOS, an AMH variant should be considered and a different AMH assay could be ordered to further analyze the serum AMH immunoactivity. A larger cohort of PCOS carriers of AMH variants will be required to fully understand how various alterations in AMH structure and/or function contribute to AMH immunodetection and PCOS phenotypic expression.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karla Largaespada for subject recruitment strategies and administrative responsibilities that were crucial for the successful studies of the normal-weight PCOS subjects. We thank Dr Sjoerd van den Berg (Department of Clinical Chemistry, Erasmus MC) for the additional automated AMH measurements.

Authors’ roles

L.R.H.: Substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. J.A.V.: Substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. A.M.: Substantial contributions to acquisition and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. G.C.: Substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. T.R.G.: Substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published. D.A.D.: Substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health (NIH) under awards P50HD071836 and P51 ODO11092 for the Endocrine Technologies Support Core (ETSC) through the Oregon National Primate Research Center; statistical analyses was supported by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR001881; and the Santa Monica Bay Woman’s Club. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of interest

J.A.V. receives royalties for the initial development of AMH assay, which are paid to the institute/lab, with no personal financial gain. Rest of authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Andersen CY, Byskov AG.. Estradiol and regulation of anti-Mullerian hormone, inhibin-A, and inhibin-B secretion: analysis of small antral and preovulatory human follicles’ fluid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:4064–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans FJ, Visser JA, Laven JS, Broer SL, Themmen AP, Fauser BC.. Anti-Mullerian hormone and ovarian dysfunction. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2008;19:340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Clinton M, Webb R.. The role of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) during follicle development in a monovulatory species (sheep). Endocrinology 2012;153:4533–4543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate RL, Mattaliano RJ, Hession C, Tizard R, Farber NM, Cheung A, Ninfa EG, Frey AZ, Gash DJ, Chow EP. et al. Isolation of the bovine and human genes for Mullerian inhibiting substance and expression of the human gene in animal cells. Cell 1986;45:685–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catteau-Jonard S, Dewailly D.. Pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome: the role of hyperandrogenism. Front Horm Res 2013;40:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang R, Dumesic D.. Polycystic ovary syndrome and hyperandrogenic states In Strauss JI,, Barbieri R (eds). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Management. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2018, 520–555. [Google Scholar]

- Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP). Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information. NLoM. (dbSNP Build ID: 153). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/dbSNP.

- den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, Roux AF, Smith T, Antonarakis SE, Taschner PE.. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat 2016;37:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Clemente N, Ghaffari S, Pepinsky RB, Pieau C, Josso N, Cate RL, Vigier B.. A quantitative and interspecific test for biological activity of anti-Müllerian hormone: the fetal ovary aromatase assay. Development 1992;114:721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Clemente N, Jamin SP, Lugovskoy A, Carmillo P, Ehrenfels C, Picard JY, Whitty A, Josso N, Pepinsky RB, Cate RL.. Processing of anti-Müllerian hormone regulates receptor activation by a mechanism distinct from TGF-beta. Mol Endocrinol 2010;24:2193–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Clemente N, Josso N, Gouedard L, Belville C.. Components of the anti-Mullerian hormone signaling pathway in gonads. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003;211:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumesic DA, Akopians AL, Madrigal VK, Ramirez E, Margolis DJ, Sarma MK, Thomas AM, Grogan TR, Haykal R, Schooler TA. et al. Hyperandrogenism accompanies increased intra-abdominal fat storage in normal weight polycystic ovary syndrome women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:4178–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumesic DA, Oberfield SE, Stener-Victorin E, Marshall JC, Laven JS, Legro RS.. Scientific statement on the diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and molecular genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr Rev 2015;36:487–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlinger AL, Kramer P, Karels B, de Jong FH, Uilenbroek JT, Grootegoed JA, Themmen AP.. Control of primordial follicle recruitment by anti-Mullerian hormone in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology 1999;140:5789–5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsic LK, Dapas M, Legro RS, Hayes MG, Urbanek M.. Functional genetic variation in the anti-Mullerian hormone pathway in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:2855–2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsic LK, Kosova G, Werstein B, Sisk R, Legro RS, Hayes MG, Teixeira JM, Dunaif A, Urbanek M.. Pathogenic anti-Mullerian hormone variants in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:2862–2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouedard L, Chen YG, Thevenet L, Racine C, Borie S, Lamarre I, Josso N, Massague J, di Clemente N.. Engagement of bone morphogenetic protein type IB receptor and Smad1 signaling by anti-Mullerian hormone and its type II receptor. J Biol Chem 2000;275:27973–27978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbavac I, Zec I, Ljiljak D, Rakos Justament R, Bukovec Megla Z, Kuna K.. Undetectable serum levels of anti-Mullerian hormone in women with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome during in vitro fertilization and successful pregnancy outcome: case report. Acta Clin Croat 2018;57:177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josso N, Rey RA, Picard JY.. Anti-Müllerian hormone: a valuable addition to the toolbox of the pediatric endocrinologist. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:674105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananen K, Markkula M, Rainio E, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Huhtaniemi IT.. Gonadal tumorigenesis in transgenic mice bearing the mouse inhibin alpha-subunit promoter/simian virus T-antigen fusion gene: characterization of ovarian tumors and establishment of gonadotropin-responsive granulosa cell lines. Mol Endocrinol 1995;9:616–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Sosulski AE, Zhang L, Saatcioglu HD, Wang D, Nagykery N, Sabatini ME, Gao G, Donahoe PK, Pepin D.. AMH/MIS as a contraceptive that protects the ovarian reserve during chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017;114:E1688–E1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevenaar ME, Laven JS, Fong SL, Uitterlinden AG, de Jong FH, Themmen AP, Visser JA.. A functional anti-Müllerian hormone gene polymorphism is associated with follicle number and androgen levels in polycystic ovary syndrome patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1310–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korchynskyi O, ten Dijke P.. Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J Biol Chem 2002;277:4883–4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurich VM, Trbovich AM, O'Neill FH, Houk CP, Sluss PM, Payne AH, Donahoe PK, Teixeira J.. Mullerian inhibiting substance blocks the protein kinase A-induced expression of cytochrome p450 17alpha-hydroxylase/C(17-20) lyase mRNA in a mouse Leydig cell line independent of cAMP responsive element binding protein phosphorylation. Endocrinology 2002;143:3351–3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney CR, Eagleson CA, Marshall JC.. Regulation of gonadotropin secretion: implications for polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med 2002;20:317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigal MW, Ingraham HA.. Bioactivation of Mullerian inhibiting substance during gonadal development by a kex2/subtilisin-like endoprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:7711–7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellatt L, Hanna L, Brincat M, Galea R, Brain H, Whitehead S, Mason H.. Granulosa cell production of anti-Mullerian hormone is increased in polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre A, Racine C, Rey RA, Fanchin R, Taieb J, Cohen-Tannoudji J, Carmillo P, Pepinsky RB, Cate RL, di Clemente N.. Most cleaved anti-Mullerian hormone binds its receptor in human follicular fluid but little is competent in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:4618–4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigny P, Merlen E, Robert Y, Cortet-Rudelli C, Decanter C, Jonard S, Dewailly D.. Elevated serum level of anti-Müllerian hormone in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: relationship to the ovarian follicle excess and to the follicular arrest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:5957–5962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DM, Kumar A, Kalra B, Shah S, Pruysers E, Vanden Brink H, Chizen D, Visser JA, Themmen AP, Baerwald A.. Detection of serum anti-Müllerian hormone in women approaching menopause using sensitive anti-Müllerian hormone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Menopause 2014;21:1277–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller-Fabre V, Carmona S, Merhi RA, Cate R, Habert R, Vigier B.. Effect of anti-Mullerian hormone on Sertoli and Leydig cell functions in fetal and immature rats. Endocrinology 1998;139:1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Massague J.. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 2003;113:685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata B, Mimouni NEH, Barbotin AL, Malone SA,, Loyens A, Pigny P, Dewailly D, Catteau-Jonard S, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Piltonen TT. et al. Elevated prenatal anti-Mullerian hormone reprograms the fetus and induces polycystic ovary syndrome in adulthood. Nat Med 2018;24:834–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teede H, Misso M, Tassone EC, Dewailly D, Ng EH, Azziz R, Norman RJ, Andersen M, Franks S, Hoeger K. et al. Anti-Mullerian Hormone in PCOS: A Review Informing International Guidelines. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2019;30:467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman RJ, International PN.. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1602–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira J, Fynn-Thompson E, Payne AH, Donahoe PK.. Mullerian-inhibiting substance regulates androgen synthesis at the transcriptional level. Endocrinology 1999;140:4732–4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira J, Maheswaran S, Donahoe PK.. Mullerian inhibiting substance: an instructive developmental hormone with diagnostic and possible therapeutic applications. Endocr Rev 2001;22:657–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trbovich AM, Sluss PM, Laurich VM, O'Neill FH, MacLaughlin DT, Donahoe PK, Teixeira J.. Mullerian Inhibiting Substance lowers testosterone in luteinizing hormone-stimulated rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:3393–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwan YG, Bruggenwirth HT, Drop SL, Wolffenbuttel KP, Madern GC, Looijenga LH, Visser JA.. A novel AMH missense mutation in a patient with persistent Mullerian duct syndrome. Sex Dev 2012;6:279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigier B, Forest MG, Eychenne B, Bezard J, Garrigou O, Robel P, Josso N.. Anti-Mullerian hormone produces endocrine sex reversal of fetal ovaries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989;86:3684–3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.