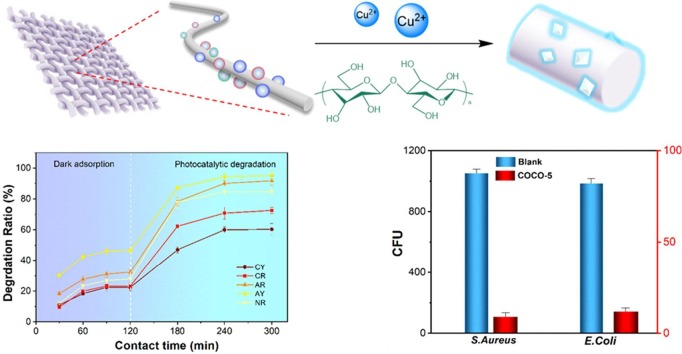

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Nanocellulose, Cuprous oxide, Cotton fabric, Photocatalytic degradation, Antibacterial activity

Highlights

-

•

In-situ synthesis of cuprous oxide (Cu2O) on cotton and coating with nanocellulose, the Cu2O crystal structures was ideal octahedron and not easy to ditch.

-

•

COCO-5 exhibited high photocatalytic degradation of dyes, and the catalytic degradation process was monitored by comprehensive technical tests.

-

•

COCO-5 exhibited highly effective antibacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli.

-

•

COCO-5 maintained high stability after multiple photocatalytic degradation of dyes or antibacterial tests, and the mechanical properties of this composite had not decreased.

Abstract

In this study, the cotton fabrics/cuprous oxide-nanocellulose (Cu2O-NC) flexible and recyclable composite material (COCO) with highly efficient photocatalytic degradation of dyes and antibacterial properties was fabricated. Using flexible cotton fabrics as substrates, Cu2O were in-situ synthesized to make Cu2O uniformly grew on cotton fibers and were wrapped with NC. The photocatalytic degradation ability of COCO-5 was verified by use methylene blue (MB), the degradation rate was as high as 98.32%. The mechanism of COCO-5 photocatalysis and the process of dye degradation were analyzed by using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum, transient photocurrent response (TPR) spectrum, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and ion chromatography (IC). This study analyzed the complete path from electron excitation to dye degradation to harmless small molecules. Qualitative and quantitative experiments demonstrate that COCO-5 has high antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli, the highest antibacterial rate can reach 93.25%. Finally, the stability of COCO-5 was verified by recycling and mechanical performance tests. The textile-based Cu2O functionalized material has photocatalytic degradation and antibacterial properties, and the preparation process is simple and convenient for repeated use, so it has great potential in wastewater treatment containing dyes and bacteria.

1. Introduction

The citizens of the bustling metropolis drink clean, non-toxic tap water, but water pollution is still a major threat to human survival in underdeveloped areas [1], [2]. There is always a tendency for industrial areas to migrate to less developed regions because of low labor costs and relatively weak environmental regulations [3], [4]. In particular, the recent COVID-19 outbreak reminds people that the threat of microorganisms and viruses to humans is also huge. It is better to develop an inexpensive material to eliminate the source of disease, that is, water pollution. The dyes in wastewater can kill aquatic plants and plankton, causing ecosystem collapse, which is very difficult to recover. If organism (including humans) drink wastewater containing dyes for a long time, even at lower concentrations, they can cause cancer [5], [6], [7], [8]. Wastewater containing a large amount of bacteria is a hotbed of disease, which not only causes various diseases, but also promotes bacterial growth and contaminates more water and water containers [9], [10], [11]. Therefore, researchers have been investing a lot of energy in the research of wastewater treatment materials.

Nanocellulose (NC) is an ideal environmentally and friendly material, it is green, sustainable and cheap. NC can be derived from plants, bacteria and marine shellfish, which have the advantages of being degradable, flexible, hydrophilic and rich in surface groups [12], [13]. NC has used as an interface “bridge” between inorganic nanomaterials and polymer materials, so NC is an ideal choice in interface chemistry of composite materials [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Cu2O is a semiconductor material because it has a narrow band gap and a suitable conduction band to facilitate absorption of visible light and exhibits photocatalytic properties, which can be used in the field of photocatalytic degradation of dyes [19], [20]. On the other hand, Cu is abundant in nature, inexpensive, and is suitable for a large amount of synthesis. These advantages make Cu2O industrial applications more preferred than similar photocatalysts such as TiO2 [21], [22], [23], [24]. Yu et al. [25] used solvothermal method to prepare Zn-doped Cu2O nanoparticles with various crystal structures, and explored the effect of Zn doping on the structure and properties of Cu2O. Their samples used for photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin, and the highest degradation rate reached 94.6%. However, the crystal structure of Zn-doped Cu2O is not clearly resolved, and it is difficult for the nanoparticles to be recycled result in secondary pollution. Nie et al. [26] incorporated Cu2O nanoparticles and graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets into microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) foam for photocatalytic degradation of MB. The use of GO improves the dispersibility of Cu2O and promotes itself stratification. Although the degradation rate is improved, the dispersion of physically mixed nanoparticles is still not satisfactory and the cost of GO is too high.

This work in propose to provide a solution that is simple to fabricate, low in cost, and recyclable. In this study, Cu2O was synthesized in-situ on cotton fabrics, NC as a “bridge” to make the dispersion of Cu2O very uniform, and not easy to fall off. The use of cotton fabrics as a substrate allows the composite to be easily reused. Among them, COCO-5 was capable of photocatalytic degradation of 98.32% MB and was capable of degrading 85% MB after repeated use for 5 times. On the other hand, COCO-5 can deal with a wide range of dyes and exhibits strong recyclable photocatalytic degradation of complex dye wastewater. The mechanisms of photocatalytic degradation were analyzed using techniques such as EPR, TPR, FTIR and IC. Combine multiple test results to demonstrate a complete dye degradation pathway. Further, COCO-5 showed excellent antibacterial ability, and the antibacterial rates against S. aureus and E. coli reached 93.25 and 89.73%, respectively, and the antibacterial rate after 5 cycles of S. aureus was still 80.99%. Through the mechanical property test, the cotton fabrics as the base material did not exhibit mechanical failure during the recycling process. In summary, this study developed a kind of recyclable cotton fabrics/Cu2O-NC composite materials with promising capabilities for dye wastewater treatment and antimicrobial applications. In-situ synthesis of nano-functional particles based on textile materials is a promising process route, and the ideal recyclable nanocomposites can be prepared by combining different organic–inorganic materials.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials.

Cotton fabrics were fabricated in our textile laboratory. Acrylic acid (AA), acrylamide (AM), Cellulose powder, hydroxylamine hydrochloride (HH, NH2OH·HCl), copper sulfate (CuSO4), ammonium persulfate (APS), ethanol, urea, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and methylene blue (MB) were purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Chemical modification of cotton fabrics and preparation of NC.

Immersed 2 cm × 2 cm cotton fabrics in the mixed solution containing 3 M AA and 3 M AM, stirred the reaction at 45 °C for 1 h, then taken out the cotton fabrics, washed it gently 5 times with deionized water, and put it in a vacuum oven to dry for 4 h. NC was obtained by dissolving cellulose powder in an alkaline urea solution (7 wt% NaOH and 12 wt% urea solution). After the reaction, the NC solutions were filtered and freeze-dried (-70 °C, 72 h) to obtain dry NC.

2.3. In-situ synthesis of octahedral Cu2O on cotton fibers.

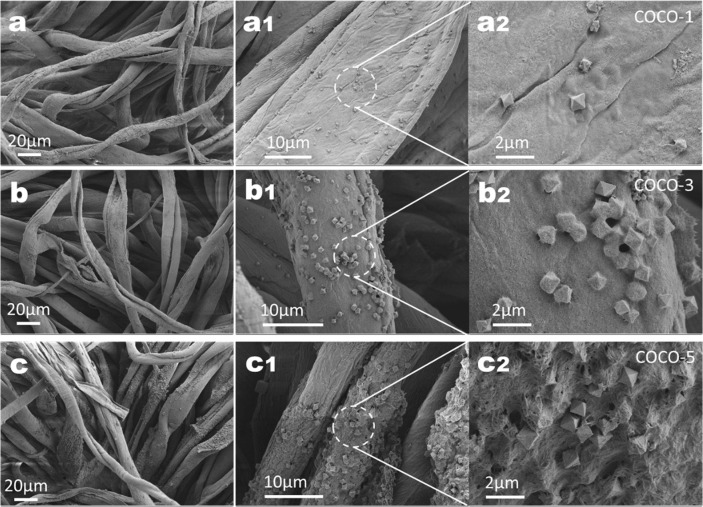

First prepare 5, 10, and 15 mM CuSO4 solutions, immersed the three chemically modified cotton fabrics in these three solutions, and then used NaOH to adjust the pH of all solutions to about 12, correspondingly added 1, 3 and 5 g NC to the CuSO4 solution in the above order (the amount of NC added were determined after preliminary experiment optimization). Next, prepared 5, 10, and 15 mL of 0.8 M HH solution, added them to the corresponding precursor solution described above, and stired the reaction at 45° C for 1 h. In this process, CuSO4 were reduced to Cu2O in brick-red by HH. After the reaction, the brick-red cotton fabrics were taken out, and the three samples were gently washed three times with ethanol, and then transferred to a vacuum oven for drying for 12 h. Finally, according to the added amount of NC mass, the three samples were named as COCO-1, COCO-3, COCO-5. The reaction mechanism is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of in-situ synthesis of Cu2O on cotton fiber.

2.4. Characterizations.

The microscopic morphology and elemental composition of the synthesis were characterized using an Ultra 55 field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The composite structure of Cu2O/NC was characterized using a JEOL 2100 transmission electron microscope (TEM). The contents of Cu2O on textile fabric were quantified through Sollar M6 atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) with air-acetylene flame. Separate hollow cathode lamps radiating at wavelengths of (Cu) 224.8 were used to determine the amount of Cu. The crystal structure was characterized using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD). The chemical functional group structure was characterized using a Nicolet 5700 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, K-Alpha) data was obtained using an electronic spectrometer. The ultraviolet absorption spectrum was characterized using a UV–visible (UV–Vis) spectrometer. The ion chromatography (IC) was carried out with instruments of Metrohm. Free radicals in the system were detected using a Bruker A300 electronic paramagnetic resonance (EPR). The transient photocurrent response (TPR) spectrum was tested using a Zahner Zennium electrochemical station. The mechanical properties were measured on Instron mechanical testing equipment.

2.5. Photocatalytic performance of dyes degradation.

Prepared 200 ppm MB solution, take three 200 mL MB solution into the beaker, put as-prepared COCO-5 (2 × 2 cm) into the beaker respectively and were stored in the dark under magnetic stirring for 120 min to reach absorption–desorption equilibrium. Subsequently, the photocatalytic reaction was performed by exposing the solution to the 350 W xenon lamp coupled with the UV cutoff filter (λ > 400 nm). The photocatalytic reactions were carried out for 120 min under irradiation. Degradation rate (%) of MB, calculated as:

| (1) |

where C0 is the initial MB concentration (ppm), and Ct is the MB concentration (ppm) at time t. The photocatalytic degradation process of other dyes (i.e. cationic yellow, cationic red, anionic red, anionic yellow, neutral red) is consistent with this. All experiments of photocatalytic degradation of dyes were carried out three times, and the average value was taken.

2.6. Antibacterial performance

Escherichia coli (E. coli, ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, ATCC 27217) were used as model Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The plate colony counting method is used to study the antibacterial ability of samples. All materials used in the antimicrobial activity test need to be sterilized in an autoclave, and the experimental operation should be carried out in a clean bench. Approximately 5 × 107 CFU/mL for bacteria and 1 × 107 CFU/mL for yeast at 37 °C for 14 h to count the amount of viable microorganism colonies. Transfer 50 μL of bacterial strains to 50 mL liquid culture medium and add Incubate in a shaking incubator at 37 °C at 100 rpm for 24 h. Then, the activated bacteria were dispensed into 50 μL of liquid culture medium, which respectively contained 0.2 mg samples, and nothing was used as a blank sample for another 24 h culture. Dilute various bacterial solutions to 100 times, and then spread 20 μL of the diluted bacterial solutions evenly on the LB agar plate. The antibacterial activity of these substances can be observed by the number of colonies, and all tests are repeated at least 3 times. Microbial colonies or average colony forming units (CFU), the equation is as follows [27], [28]:

| (2) |

where N0 is the mean number of bacteria on the pure liquid medium with full cells, and N1 is the mean number of bacteria on the COCO-5.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Morphological observation

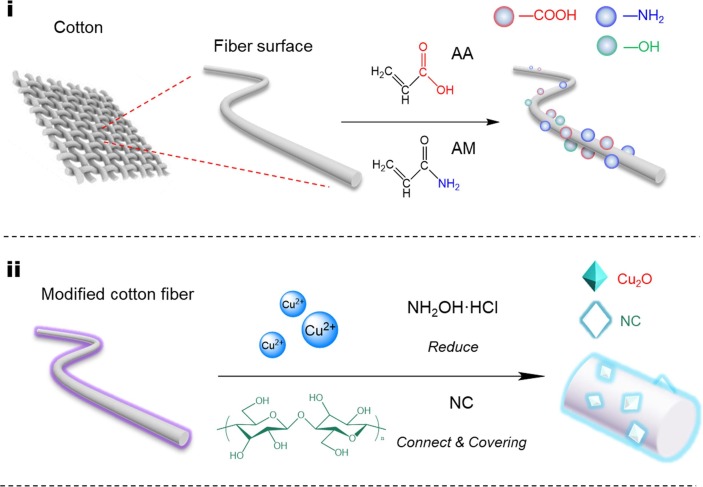

Firstly, the Cu2O-NC composite sample without cotton fabrics was prepared, and its micro composite structure and crystal structure were analyzed by TEM. As can be seen from Fig. 2 a, Cu2O were dispersed in the middle of the NC and had quadrilateral or elliptical structures of varying sizes, with Cu2O having diameter of between about 20–40 nm. The (1 0 0) and (2 0 0) crystal planes of Cu2O were observed under high resolution TEM, and their interplanar spacings were 0.30 and 0.21 nm, respectively (Fig. 2b) [29], [30]. The above observations prove that the Cu2O prepared by the research method has good structures and NC assists in the dispersion of Cu2O.

Fig. 2.

(a-b) TEM images of Cu2O/NC and the lattice lines exhibited at high magnification.

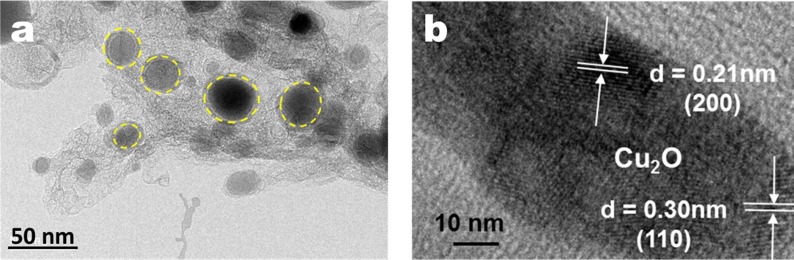

In order to explore the optimal synthesis conditions, the concentration of CuSO4 and NC were adjusted to prepare Cu2O in-situ on the surface of cotton fabrics. Some significant differences in Cu2O content of three samples was observed by FE-SEM (Fig. 3 ). The COCO-1 cotton fibers were loaded with only a small amount of Cu2O-NC, and most of the cotton fibers were bare. At high magnification, it can be seen that the Cu2O of octahedral structure were scattered on the surface of the fibers and is not wrapped by the NC (Fig. 3a-a2). Fig. 3b-b2 showed that the Cu2O on the cotton fiber of COCO-3 were obviously increased, and the distribution was relatively uniform. The Cu2O portion of the cotton fibers were wrapped by the NC, which helped prevent Cu2O from falling off easily, but some of the Cu2O were exposed. COCO-5 achieved an ideal composite structure, cotton fibers had been densely attached by Cu2O-NC, while NC coated most of the Cu2O on the surface of the fiber with some pores (Fig. 3c-c2). NC were clustered together again through the hydrogen bonds network on the cotton fibers, leaving some pores while constructing the NC three-dimensional network, which was conducive to the reaction of the liquid phase with the encapsulated Cu2O. Furthermore, the AAS was utilized to accurate analyze content of Cu2O on composite sample for COCO-1, COCO-3 and COCO-5 was 15.78, 21.38, and 30.27 mg/g, corresponding to the FE-SEM analyses. Notably, sample COCO-5 showed the highest Cu2O content when obtained with the highest concentration of synthetic raw material. On the other hand, combined with some preliminary experiments (including photocatalytic degradation of dyes and antibacterial tests), the COCO-5 was the idea sample for the recyclable photocatalytic and antimicrobial applications.

Fig. 3.

FE-SEM images of (a-a2) COCO-1, (b-b2) COCO-3 and (c-c2) COCO-5.

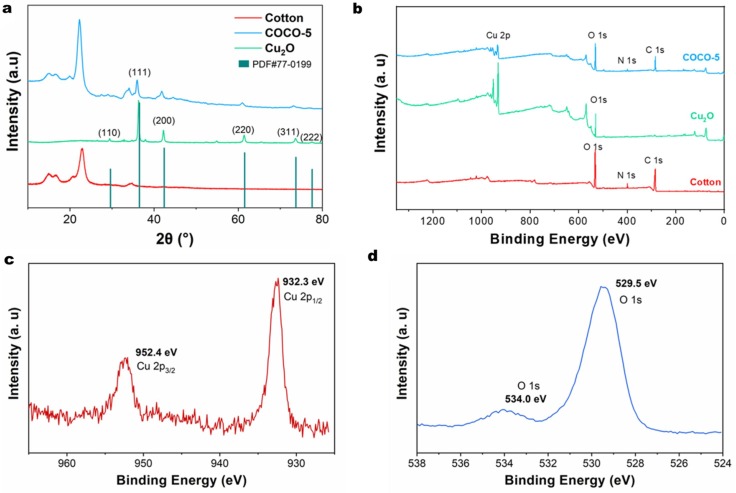

3.2. Crystal structure and chemical composition analysis

As shown in Fig. 4 , XRD patterns and XPS spectra were used to analyze the crystal structures of Cu2O and the composite structures of Cu2O/ cotton fabrics. Fig. 4a clearly shows the XRD patterns of the crystal structures of COCO-5 and pure Cu2O. The diffraction peaks observed at 2θ = 29.36°, 36.45°, 42.38°, 61.57°, 73.69° and 77.65° correspond to the (1 1 0), (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), (3 1 1) and (2 2 2) crystal planes of Cu2O (JCPDS no: 77–0199) [31], [32], respectively, as indicated in the Fig. 4a. This is the XRD diffraction patterns of the crystal structures of octahedral Cu2O [33], [34]. At the same time, the growth of octahedral Cu2O in the FE-SEM images was verified (Fig. 3c2). The intensities of the diffraction peaks of COCO-5 is higher than that of pure Cu2O, which because the cotton fiber as a growth substrate promotes the formation of better Cu2O crystal structures [35]. The TEM images of Fig. 2 also confirmed this phenomenon, in the absence of cotton fabrics as a growth substrate, the crystal structures of Cu2O were close to an ellipse rather than a regular octahedron. In contrast, there is no Cu2O crystal diffraction peak on the cotton fabrics because the pure cotton does not carry any Cu2O [36]. Fig. 4b is XPS analysis of cotton fabrics, Cu2O and COCO-5. The peaks of C 1 s, N 1 s and O 1 s were detected at 285.4, 399.7 and 532.2 eV in cotton fabrics, and the peaks of O 1 s and Cu 2p were detected at 529.5 and 931.7 eV in Cu2O, and the above four peaks appeared simultaneously in COCO-5 [37], [38]. In detail, on the XPS spectrum of Cu 2p (Fig. 4c), the peaks located at 932.3 and 952.4 eV are ascribed to the Cu 2p1/2 and Cu 2p3/2 [39]. In Fig. 4d, the O 1 s can be fitted into 529.5 and 534.0 eV, which were attributed to lattice oxygen of Cu–O bonds and surface-adsorbed oxygen species [40]. The results of XRD and XPS prove that Cu2O and cotton fabrics can be well combined with the assistance of NC.

Fig. 4.

(a) XRD patterns and (b) XPS spectra of COCO-5, Cu2O and cotton fabrics. (c) Cu 2p and (d) O 1 s spectra of COCO-5.

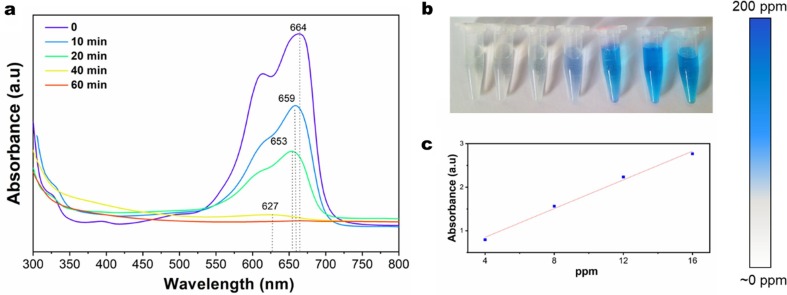

3.3. Photocatalytic degradation of MB and its mechanism analysis

COCO-5 verified its photocatalytic performance by degrading MB under irradiation with a xenon light, and the concentration of MB was monitored by UV–vis, as shown in Fig. 5 . Five reaction times were set to degrade MB using COCO-5, which were 0, 10, 20, 40 and 60 min, respectively (Fig. 5a). The concentration of MB after degradation was then calculated from the corresponding absorption intensity in the standard curve (Fig. 5b-c). From the UV–vis absorption peak (Fig. 5a), the absorption peaks at 664 nm of MB were be weaker and blue-shifted, and the color of the MB solution also changed from blue to colorless. This indicates that the reduction of the chromophore group can determine the occurrence of degradation, and the blue shift of the peak indicated that the energy required for the electronic transition increases to form an intermediate product [41]. After 60 min, almost no MB was left in solution (1.68%), COCO-5 shown excellent photocatalytic degradation property. More importantly, COCO-5 can be easily taken out after photocatalytic degradation of MB, avoiding the problem of secondary pollution, this is a simple and effective solution for photocatalytic degradation of dyes.

Fig. 5.

(a) UV–vis spectra and (b) optical image of MB after different photocatalytic degradation time, (c) UV–vis standard curve with concentrations corresponding to absorbance. The right color ruler is the correspondence between colors and concentrations.

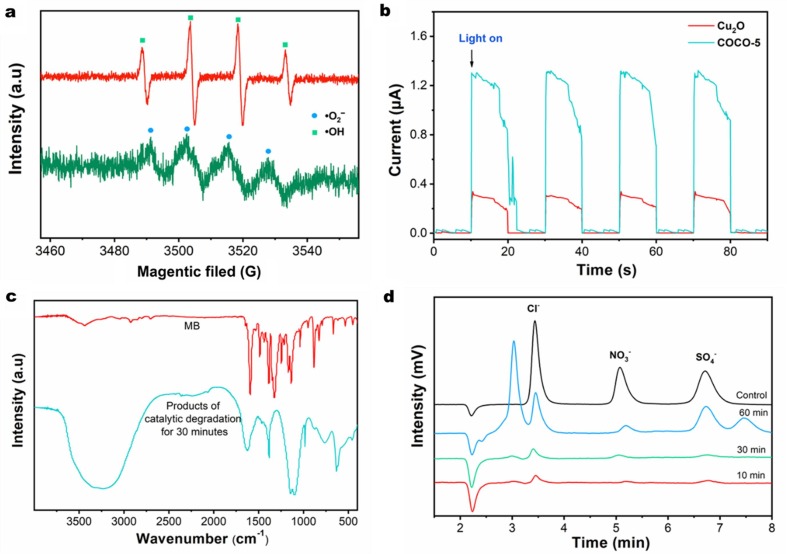

A comprehensive test analysis was carried out on the mechanism and process of photocatalytic degradation of MB by COCO-5. Fig. 6 a shows the presence of free radicals in the COCO-5 catalytic system by EPR spectroscopy. Four characteristic peaks of •OH and four characteristic peaks of •O2 – can be observed by analysis, indicating that •OH and •O2 – radicals will play a major role in the process of degradation [42]. Fig. 6b is a TPR spectrum of COCO-5 and pure Cu2O turned on and off under visible light. Compared to Cu2O, COCO-5 had a stronger photocurrent response and was stable. This shows that the photo-electric charge separation rate of COCO-5 was higher than that of pure Cu2O, and the good dispersion of Cu2O on cotton fibers accelerated the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes, which made COCO-5 have high photocatalytic activity [43]. Fig. 6c is a FTIR spectra of MB before and after degradation. Compared to MB, products had a –OH characteristic peak at 3300 cm−1, a –NO2 characteristic peak at 1630 cm−1, 1649 cm−1 was an organic nitrate characteristic peak, the 1100 and 1150 cm−1 characteristic peak were the hydroxyl deformation vibration on secondary and tertiary carbons. A strong absorption peak of N-O at the 870 cm−1 indicated that the degradation product had been degraded into a simple carbon chain. In particular, the presence of –NO2 also demonstrates the oxidative degradation of MB molecules [44], [45]. The IC (Fig. 6d) further demonstrates this result and will be explained in detail in conjunction with the mechanism explained in the next section.

Fig. 6.

(a) EPR spectra of COCO-5 with visible light irradiation, •O2– in methanol dispersions and •OH in aqueous dispersions, (b) transient photocurrent response (TPR) spectra of Cu2O and COCO-5, (C) FTIR spectra of MB and products of photocatalytic degradation for 30 min, and (d) ion chromatography (IC) of degradation products.

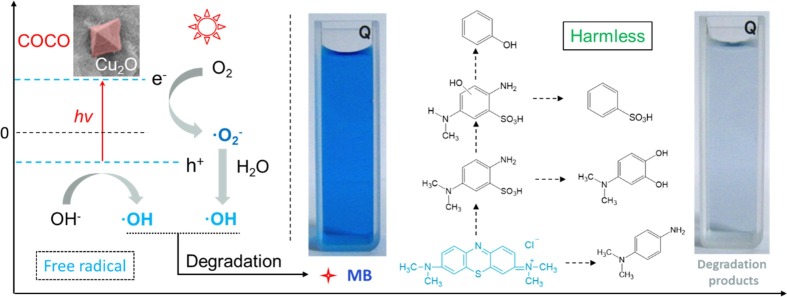

In theory, the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of Cu2O are calculated according to the following equations: EVB = κ − E0 + 0.5Eg and ECB = EVB − Eg, where E VB and E CB are the VB and CB potentials respectively, E 0 is the energy of free electrons on the hydrogen scale (ca. 4.5 eV), E g is the band gap energy, and κ is the electronegativity computed from the geometric mean of the electronegativities for the constituent atoms. Therefore, the CB and VB potentials of Cu2O are approximately −0.28 and 1.92 eV, respectively. During visible light irradiation of COCO-5, a series of physicochemical reactions occurred in the surface of COCO-5 and solution (Fig. 7 ), including: i, Cu2O absorbed energy (hv) to generate electrons (e-) and holes (h+), and these e- and h+ react further with oxygen and water to produce superoxide radicals (•O2 –) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), related free radical reactions are as follows:

Fig. 7.

Schematic illustration of visible light irradiated COCO-5 to generate free radicals and MB degradation process.

Cu2O + hv → Cu2O (e-, h+) (3)

O2 + e- → •O2 – (4)

H2O + h+ → •OH + H+ (5)

•O2 – + H+ + e- → H2O2 (6)

H2O2 + e- → •OH + OH– (7)

ii, firstly, the ·OH radical attacks the -S = bond and the -N = bond of MB to interrupt the MB molecule. Secondly, under the function of •O2 – and •OH, the MB split product is oxidized to phenol, diphenol, etc., because phenol and diphenol have an electron donor –OH present on the benzene ring, which is beneficial to •OH electrical attacks, especially in the presence of –OH on the ortho and para positions. Phenol can be oxidized to hydroquinone, catechol, resorcinol, etc., and diphenol can be quickly oxidized to benzoquinone. In the third step, the intermediate product of the aromatic ring is further oxidized by •OH into a short-chain carboxylic acid such as fumaric acid, oxalic acid, formic acid, etc., and these short-chain carboxylic acids can be rapidly degraded into CO2 and H2O [46], [47], [48], [49]. Analysis of the IC verified this degradation process (Fig. 6d). Eventually, under this series of physicochemical reactions, MB is degraded and water is harmless. The gradual degradation process is shown in Fig. 7.

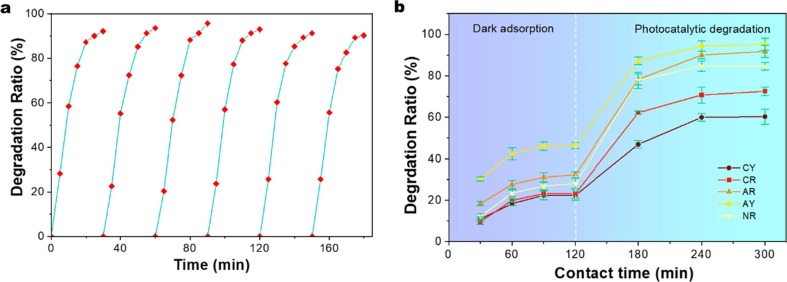

One of the advantages of this study is that it can be easily reused because it is easy to remove the COCO-5 from the liquid. Six photocatalytic degradation cycles were set to test the stability of COCO-5. We performed the cycling tests of sample by simply washing with distilled water for the next cycle of photocatalytic. It can be seen from Fig. 8 a that the photocatalytic activity of COCO-5 can still be maintained above 85% after 6 cycles, which indicates that it has good durability. This performance is significantly better than the Cu2O photocatalytic material without the cotton fabrics [50], [51], which indicates that the cotton fiber is a good matrix to promote stability, and NC helps Cu2O to anchor better on the fiber. Fig. 8b shows the photocatalytic degradation properties of COCO-5 for a variety of dyes, including CY (cationic yellow), CR (cationic red), AR (anionic red), AY (anionic yellow) and NR (neutral red). At first step, the concentration of the five dyes decreased by 10–50% when in the dark treatment environment (purple part). In this 120 min, COCO-5 mainly showed the ability to adsorb dyes. In the second step (light blue part), the species dye were rapidly degraded under visible light irradiation, and COCO-5 mainly exhibited photocatalytic degradation properties. This situation indicates that COCO-5 can degrade the chromophore groups (azo group) of a variety of dyes [52], their molecular formula is shown in the Fig. S1 (Supplementary data,) thereby having the potential to handle complex dye wastewater.

Fig. 8.

(a) Cycle photocatalytic degradation of MB by COCO-5, and (b) photocatalytic activity of COCO-5 to a variety of dyes (CY: cationic yellow; CR: cationic red; AR: anionic red; AY: anionic yellow; NR: neutral red).

3.4. Antibacterial performance test

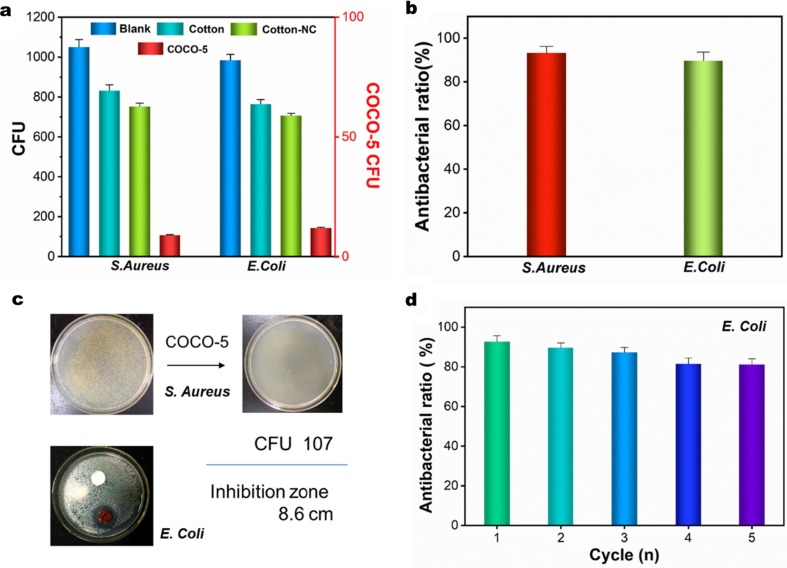

Generally, Cu2O has strong antibacterial properties, so the samples in this study have also been tested for antibacterial. Similarly, the antibacterial properties of COCO-5 in the aqueous phase can be easily reused. S. Aureus and E. Coli were used to represent Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. COCO-5 was tested for antimicrobial property using plate colony counting method. Fig. 9 a shows that the CFU on the medium after being treated with COCO-5 for 30 min had dropped to 107 (S. Aureus) and 143 (E. Coli), and the blank (nothing on it) CFU were still 1050 and 984 (Fig. 9c). At the same time, we prepared pure cotton and cotton-NC composite fabrics to test the antibacterial properties. The results showed that the antibacterial properties of pure cotton and cotton-NC composite fabrics were not excellent. Although their tested CFU was lower than that of the blank control group, they were all at a high CFU value, which did not achieve the desired antibacterial effect. The antibacterial rates (AR) of COCO-5 to S. Aureus and E. Coli reached 93.25 and 89.73%, respectively (Fig. 9b). This indicates that the cotton fabrics loaded with Cu2O had a strong antibacterial activity. Usually, the Cu2O surface could generate hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with antibacterial effect, and H2O2 binds to the bacterial cell membrane to affect its permeability and respiratory function, leading to bacterial apoptosis [53]. Photos of CFU reduction of S. aureus and a significant inhibition zone of E. Coli can be seen in Fig. 9c. The maximum inhibition zone of COCO-5 against E. Coli was 8.6 cm, showing an excellent antibacterial effect. The COCO-5 reuse ability was verified by 5 E. Coli antibacterial cycles (Fig. 9d). After 5 cycles, the antibacterial rate of COCO-5 to E. Coli was still maintained at 80.99%, showing excellent stability.

Fig. 9.

(a) Bacterial reduction of COCO-5, cotton fabrics, cotton fabrics-NC and blank (nothing on it) samples, (b) antibacterial rate of COCO-5 against S. Aureus and E. Coli, (c) Photos of the bacterial CFU reduction of S. Aureus and the zone of inhibition of E. Coli, and (d) antibacterial ratio to E. Coli of COCO-5 after 5 cycles.

3.5. Mechanical stability test

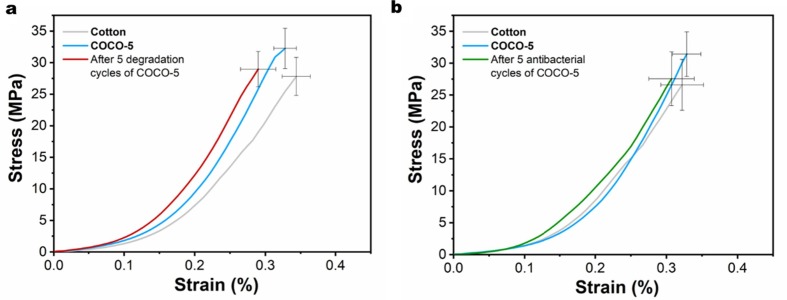

The stability after multiple cycles of COCO-5 was also verified by mechanical performance testing (Fig. 10 ). Divided into two groups tested mechanical properties of cotton fabrics, unused COCO-5 and COCO-5 used five times. In the first group (Fig. 10a), compared to cotton fabrics and unused COCO-5, the stress and strain of COCO-5 after photocatalytic degradation (5 times) decreased slightly, which may be due to the visible light radiation that reduces the mechanical properties of the cotton fibers[54], [55]. In the second group (Fig. 10b), the stress and strain of COCO-5 decreased slightly after antibacterial experiments (5 cycles) compared to the unused COCO-5. This may be because the bacterial medium weakened the strength and toughness of cotton fibers. However, compared with pure cotton fabric, the difference in COCO-5 stress and strain after 5 antibacterial experiments was slight, which verified the durability of COCO-5 in mechanical properties.

Fig. 10.

Stress–strain curves: (a) cotton fabrics, unused COCO-5 and COCO-5 after 5 photocatalytic degradation cycles of dyes, (b) cotton fabrics, unused COCO-5 and COCO-5 after 5 antibacterial cycles.

4. Conclusion

In this study, Cu2O was synthesized in-situ on cotton fabrics and used NC as “bridge”, which ensured the good dispersion of Cu2O and allowed it to be recycled. The fabricated cotton fabrics/Cu2O-NC composite material can efficiently degrade the dye by photocatalysis, and is also an ideal antibacterial material. A variety of technical tests have analyzed the photocatalytic degradation mechanism of cotton fabrics/Cu2O-NC, and the practicality of this research strategy has been illustrated by recycle using. In-situ synthesis of nano-functional particles based on textile materials is a promising process route, and the ideal recyclable nanocomposites can be prepared by combining different organic–inorganic materials.

5. Credit author statement

Xiuping Su: synthesized the composite materials and wrote the paper. Wei Chen: measured the antibacterial experiments. Yanna Han: designed and supervised the experiments. Duanchao Wang: synthesized the composite materials and wrote the paper. Juming Yao: designed and supervised the experiments.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of competing interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Technology Planning Project of Shaoxing (2018C30012; 2017B70069), the National Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (GG19E030011), and the Project of Shaoxing University Yuanpei College (KY2018Z01).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147945.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Barnett J., Rogers S., Webber M., Finlayson B., Wang M. Sustainability: transfer project cannot meet China's water needs. Nature. 2015;527:295–297. doi: 10.1038/527295a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song M., Wang R., Zeng X. Water resources utilization efficiency and influence factors under environmental restrictions. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018;184:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashino T., Otsuka K. Springer; 2016. Industrial districts in history and the developing world. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngo T.H., Hien T.T., Thuan N.T., Minh N.H., Chi K.H. Atmospheric PCDD/F concentration and source apportionment in typical rural Agent Orange hotspots, and industrial areas in Vietnam. Chemosphere. 2017;182:647–655. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miklos D., Remy C., Jekel M., Linden K.G., Drewes J.E., Hubner U. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment – A critical review. Water Res. 2018;139:118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu J., Zhang P., An W., Liu L., Liang Y., Cui W. In-situ Fe-doped g-C3N4 heterogeneous catalyst via photocatalysis-Fenton reaction with enriched photocatalytic performance for removal of complex wastewater. Applied Catalysis B-environmental. 2019;245:130–142. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi W., Ren H., Li M., Shu K., Xu Y., Yan C., Tang Y. Tetracycline removal from aqueous solution by visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation with low cost red mud wastes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;382 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y., Chen M., Liu H., Zhu Y., Wang D., Yan M. Adsorptive removal of dye and antibiotic from water with functionalized zirconium-based metal organic framework and graphene oxide composite nanomaterial Uio-66-(OH)2/GO. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;525 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown E.D., Wright G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegab H.M., ElMekawy A., Zou L., Mulcahy D., Saint C.P., Ginic-Markovic M. The controversial antibacterial activity of graphene-based materials. Carbon. 2016;105:362–376. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Podporska-Carroll J., Myles A., Quilty B., McCormack D.E., Fagan R., Hinder S.J., Dionysiou D.D., Pillai S.C. Antibacterial properties of F-doped ZnO visible light photocatalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017;324:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim H.J., Yim E.C., Kim J.H., Kim S.J., Park J.Y., Oh I.K. Bacterial nano-cellulose triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy. 2017;33:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W., Li B., Meng M., Cui Y., Wu Y., Zhang Y., Dong H., Feng Y. Bimetallic Au/Ag decorated TiO2 nanocomposite membrane for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline and bactericidal efficiency. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;487:1008–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D.C., Yu H.Y., Qi D., Ramasamy M., Yao J.M., Tang F., Tam K.C., Ni Q.Q. Supramolecular Self-assembly of 3D Conductive Cellulose Nanofiber Aerogels for Flexible Supercapacitors and Ultrasensitive Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:24435–24446. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b06527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S., Lu A., Zhang L. Recent advances in regenerated cellulose materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016;53:169–206. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nechyporchuk O., Belgacem M.N., Bras J. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: A review of recent advances. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016;93:2–25. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rol F., Belgacem M.N., Gandini A., Bras J. Recent advances in surface-modified cellulose nanofibrils. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019;88:241–264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kracher D., Scheiblbrandner S., Felice A.K., Breslmayr E., Preims M., Ludwicka K., Haltrich D., Eijsink V.G., Ludwig R. Extracellular electron transfer systems fuel cellulose oxidative degradation. Science. 2016;352:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo J., Steier L., Son M.K., Schreier M., Mayer M.T., Grätzel M. Cu2O nanowire photocathodes for efficient and durable solar water splitting. Nano Lett. 2016;16:1848–1857. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b04929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales-Guio C.G., Liardet L., Mayer M.T., Tilley S.D., Grätzel M., Hu X. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen production in alkaline solutions using Cu2O coated with earth-abundant hydrogen evolution catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:664–667. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S., Parlett C.M., Isaacs M.A., Jowett D.V., Douthwaite R.E., Cockett M.C., Lee A.F. Facile synthesis of hierarchical Cu2O nanocubes as visible light photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B. 2016;189:226–232. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee A., Libera J.A., Waldman R.Z., Ahmed A., Avila J.R., Elam J.W., Darling S.B. Conformal nitrogen-doped TiO2 photocatalytic coatings for sunlight-activated membranes. Adv. Sustainable Systems. 2017;1:1600041. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Errokh A., Ferraria A.M., Conceicao D.S. Controlled growth of Cu2O nanoparticles bound to cotton fibres. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;141:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia Y.M., He Z.M., Su J.B., Tang B., Liu Y. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of Z-scheme Cu2O/Bi5O7I nanocomposites. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018;29:15271–15281. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X., Zhang J., Zhang J., Niu J., Zhao J., Wei Y., Yao B. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using Zn-doped Cu2O particles: analysis of degradation pathways and intermediates. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;374:316–327. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie J., Li C.Y., Jin Z.Y., Hu W.T., Wang J.H., Huang T., Wang Y. Fabrication of MCC/Cu2O/GO composite foam with high photocatalytic degradation ability toward methylene blue. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;223 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D.C., Yu H., Song M.L., Yang R.T., Yao J.M. Superfast adsorption-disinfection cryogels decorated with cellulose nanocrystal/zinc oxide nanorod clusters for water-purifying microdevices. ACS Sustainable Chemistry Engineering. 2017;5:6776–6785. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W., Feng H.M., Liu J.G., Zhang M.T., Liu S., Feng C., Chen S.G. A photo catalyst of cuprous oxide anchored MXene nanosheet for dramatic enhancement of synergistic antibacterial ability. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;386 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L.H., Sui Y.M., Zhao W.Y., Fu W.Y., Yang H.B., Zhang L., Zhou X.M., Cheng S.L., Ma J.W., Zhao H., Li M.H. One-pot shorter time synthesis of Cu2O particles and nanoframes with novel shapes. CrystEngComm. 2011;13:6265–6270. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X.H., Xue J.B., Zhou W., Zhang Y.G., Jiang D.H., Wu L.Q. Photocatalytic performance enhancement of CuO/Cu2O heterostructures for photodegradation of organic dyes: Effects of CuO morphology. Applied Catalysis B Environmental An International Journal Devoted to Catalytic Science & Its Applications. 2017;211:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Z.M., Tang B., Su J.B., Xia Y.M. Fabrication of novel Cu2O/Bi24O31Br 10 composites and excellent photocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018;29:19544–19553. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia Y.M., He Z.M., Su J.B., Hu K.J. Construction of novel Cu2O/PbBiO2Br composites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics: Mater Electron. 2019;30:9843–9854. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H.L., Sato R., Yamaguchi A., Kimura M., Haruta M., Kurata H., Teranishi T. Formation of pseudomorphic nanocages from Cu2O nanocrystals through anion exchange reactions. Science. 2016;351:1306–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Y.C., Hsu L.C., Lin C.Y., Chiang C.L., Chou C.M., Wu W.W., Chen S.Y., Lin Y.G. Sandwich-nanostructured n-Cu2O/AuAg/p-Cu2O Photocathode with Highly Positive Onset Potential for Improved Water Reduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:38625–38632. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b11737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li P., Li D., Liu L., Li A., Luo C., Xiao Y., Hu J., Jiang H., Zhang W. Concave structure of Cu2O truncated microcubes: PVP assisted 100 facet etching and improved facet-dependent photocatalytic properties. CrystEngComm. 2018;20:6580–6588. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed H.B., Emam H.E. Layer by layer assembly of nanosilver for high performance cotton fabrics. Fibers Polym. 2016;17:418–426. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Permyakova A.A., Herranz J., El Kazzi M., Diercks J.S., Povia M., Mangani L.R., Horisberger M., Pătru A., Schmidt T.J. On the Oxidation State of Cu2O upon Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: An XPS Study. ChemPhysChem. 2019;20:3120–3127. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201900468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaviyarasan K., Anandan S., Mangalaraja R.V., Sivasankar T., Ashokkumar M. Sonochemical synthesis of Cu2O nanocubes for enhanced chemiluminescence applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;29:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui W.Q., An W.J., Liu L., Hu J.S., Liang Y.H. Novel Cu2O quantum dots coupled flower-like BiOBr for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminant. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014;280:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao X., Yang H., Cui Z., Li R., Feng W. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of Ag-Bi4Ti3O12 nanocomposites prepared by a photocatalytic reduction method. Mater. Technol. 2017;32:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma A., Dutta R.K. Studies on the drastic improvement of photocatalytic degradation of acid orange-74 dye by TPPO capped CuO nanoparticles in tandem with suitable electron capturing agents. RSC Adv. 2015;5:43815–43823. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo B., Xu D., Li D., Wu G., Wu M., Shi W., Chen M. Fabrication of a Ag/Bi3TaO7 plasmonic photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity for degradation of tetracycline. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:17061–17069. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b03535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu W., Moehl T., Cui W., Wick-Joliat R., Zhu L., Tilley S.D. Extended Light Harvesting with Dual Cu2O-Based Photocathodes for High Efficiency Water Splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018;8:1702323. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chithambararaj A., Sanjini N., Bose A.C., Velmathi S. Flower-like hierarchical h-MoO3: new findings of efficient visible light driven nano photocatalyst for methylene blue degradation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013;3:1405–1414. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen M.L., Zhang F.J., Oh W.C. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by CNT/TiO2 composites prepared from MWCNT and titanium n-butoxide with benzene. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2008;45:651–657. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rauf M.A., Meetani M.A., Khaleel A., Ahmed A. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue using a mixed catalyst and product analysis by LC/MS. Chem. Eng. J. 2010;157:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houas A., Lachheb H., Ksibi M., Elaloui E., Guillard C., Herrmann J.M. Photocatalytic degradation pathway of methylene blue in water. Appl. Catal. B. 2001;31:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia S., Zhang L., Pan G., Qian P., Ni Z. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue with a nanocomposite system: synthesis, photocatalysis and degradation pathways. PCCP. 2015;17:5345–5351. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03877k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia Y.M., He Z.M., Hu K.J., Tang B., Su J.B., Liu Y., Li X.P. Fabrication of n-SrTiO3/p-Cu2O heterojunction composites with enhanced photocatalytic performance. J. Alloy. Compd. 2018;753:356–363. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L., Yang W., Sun W., Li Q., Shang J.K. Creation of Cu2O@ TiO2 composite photocatalysts with p–n heterojunctions formed on exposed Cu2O facets, their energy band alignment study, and their enhanced photocatalytic activity under illumination with visible light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:1465–1476. doi: 10.1021/am505861c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu L., Qi Y., Hu J., Liang Y., Cui W. Efficient visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and enhanced photostability of core@ shell Cu2O@ g-C3N4 octahedra. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015;351:1146–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jian L., Cai D., Su G., Lin D., Lin M., Li J., Liu J., Wan X., Tie S., Lan S. The accelerating effect of silver ion on the degradation of methyl orange in Cu2O system. Appl. Catal. A. 2016;512:74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu W., Zhao W., Wu Y., Zhou C., Li L., Liu Z., Dong J., Zhou K. Antibacterial behaviors of Cu2O particles with controllable morphologies in acrylic coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019;465:279–287. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiener J., Chládová A., Shahidi S., Peterová L. Effect of UV irradiation on mechanical and morphological properties of natural and synthetic fabric before and after nano-TiO2 padding. Autex Research Journal. 2017;17:370–378. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shokrieh M.M., Bayat A. Effects of ultraviolet radiation on mechanical properties of glass/polyester composites. J. Compos. Mater. 2007;41:2443–2455. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.