Abstract

The spontaneous eye blink rate (EBR) has been linked to different cognitive processes and neurobiological factors. It has also been proposed as a putative index for striatal dopaminergic function. While estradiol is well-known to increase dopamine levels through multiple mechanisms, no study up to date has investigated whether the EBR changes across the menstrual cycle. This question is imperative however, as women have sometimes been excluded from studies using the EBR due to potential effects of their hormonal profile. Fifty-four women were tested for spontaneous EBR at rest in three different phases of their menstrual cycle: during menses (low progesterone and estradiol), in the pre-ovulatory phase (when estradiol levels peak and progesterone is still low), and during the luteal phase (high progesterone and estradiol). No significant differences were observed across the menstrual cycle and Bayes factors show strong support for the null hypothesis. Instead, we observed high intra-individual consistency of the EBR in our female sample. Accordingly, we strongly encourage including female participants in EBR studies, regardless of their cycle phase.

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour, Cognitive neuroscience, Oculomotor system

Introduction

For more than 70 years1, the spontaneous eye blink rate (EBR) has been used as a physiological measure related to diverse neurocognitive and biological factors2. These factors range from individual genetic make-up3 and neuropsychiatric disorders4, to psychological personality traits5,6, attentional regulation7, learning processes8,9, cognitive flexibility3,10 and other executive functions11. Some of these effects have been suggested to reflect dopaminergic functioning12–14. Given its non-invasive nature, the EBR has been used as a proxy for striatal dopamine (DA) levels as an alternative to direct measurements like positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT)15.

Converging evidence from animal and human studies show a positive correlation of the EBR to DA levels in the striatum. For instance, the EBR correlates positively with DA levels in the caudate nucleus of non-human primates16. A number of studies have shown that DA agonists and antagonists increase and decrease EBRs, respectively, both in animals17–20, and healthy humans21–23. Likewise, studies in human patients with abnormal dopaminergic function show a reduced EBR for Parkinson’s disease4,12,24 and increased EBR for schizophrenia25,26 and Tourette syndrome27. Additionally, reduced EBR has been proposed as putative index for reduced D2/3-receptor availability, in relation to chronic drug consumption28, increased alcohol/nicotine use, and gambling problem severity29 However, little is known about the neural circuitry underlying inter-individual differences in the EBR. Kaminer et al.19 suggested a model for humans and rodents, in which the trigeminal complex is altered by striatal DA levels, changing the EBR. This relation to the dopaminergic system is not without inconsistencies and some studies reported evidence to the contrary30,31. A causal relationship has recently been established between the right angular gyrus and the EBR32. The gray matter volume in the right angular gyrus was positively correlated to the EBR, and a disruption of activity in this area by transcranial magnetic stimulation decreased the EBR.

Independently of the neural basis of the EBR, several factors have been consistently reported to modulate it. Among others, the EBR has been observed to change following a circadian33 and seasonal rhythm34, during different cognitive states35 and with age, although not in a consistent pattern for the latter. An increase from childhood to maturity appears to be steady11,36–38, but results are inconsistent regarding the age-related decline. Specifically, age seems to interact with sex, another factor reported to modulate the EBR. Around menopause, women experience a significant drop in EBR, whereas in men, the EBR decreases steadily39. Although sex differences are not consistently reported6,11,40–42, studies demonstrating a main effect of sex, usually report higher EBR in women than in men3,8,9,43–45. Some of these effects have been attributed to endogenous variations in ovarian hormone levels of women throughout their life span39. Furthermore, endogenous fluctuations in ovarian hormones across the menstrual cycle have been assumed to play a role in EBR modulation46. However, the relationship of the EBR to such endogenous hormone fluctuations has never been explicitly researched.

Indeed, both estradiol and progesterone have neuroactive effects and are known to modulate dopaminergic functioning47. Specifically, estradiol increases the synthesis, release, reuptake and turnover of DA in the prefrontal cortex and the striatum and modifies basal firing rates of dopaminergic neurons48–52. Research on progesterone’s effects on the other hand, is inconsistent and scarce53. For instance, in the striatum, progesterone has been shown either to potentiate and enhance estrogenic actions, or to oppose them (thus inhibiting DA release); depending on the mode of administration, concentration and prior administration of oestrogens54,55. While these effects are well-known, especially in animal research, up to date no study has investigated the EBR across the menstrual cycle. In naturally cycling women, ovarian hormone levels fluctuate over approximately 28–29 days and three different hormonal milieus can be distinguished. At the beginning, during menses, circulating levels of estradiol and progesterone are still low. Then estradiol starts to rise and peaks right before ovulation, while progesterone is still low. After ovulation, the luteal phase is characterized by increasing levels of progesterone and medium estradiol levels56. However, some of the studies including the EBR as putative index for DA system only include males5,29,57, and others explicitly state that female sex hormones could affect their measurements58. This sex bias towards male subjects is even more pronounced in animal research (16,59 in monkeys19, in rodents). Human EBR studies that include women do not control for menstrual cycle9,45, or do so very loosely34.

Given this conjuncture in which no research has been carried out to date, but still scientists face the decision on how to deal with female subjects, it is of the uttermost importance to determine if and how the EBR changes across the menstrual cycle. Based on previous literature supporting the enhancing effect of estradiol on striatal DA function, and the positive relationship between the latter and the EBR, we expect the EBR to increase during the pre-ovulatory phase, when estradiol is high and progesterone low.

Materials and methods

Participants

Eighty-three young healthy right-handed women were recruited from the University of Salzburg and through social media, as well as from the samples of previous studies. Twenty-nine participants were excluded prior to analyses because of inconsistencies between hormone values and cycle phase as calculated based on self-reports (see “Hormone analysis” section). Therefore, analyses were performed in 54 women with an age range between 18 and 35 years (Mage = 23.95, SD = 3.68). We specifically used this range in order to maintain the sample as homogeneous as possible, given that sex hormones levels vary after 35 years old60, and an EBR decline has been related to perimenopause in women39. All of them had a regular menstrual cycle (Mcycle length = 28.63 days, SD = 2.24) and had not used hormonal contraceptives within the previous 6 months. Regular menstrual cycle was defined as ranging between 21 and 35 days and a variability of cycle length between individual cycles of less than 7 days56. Other exclusion criteria were neurological, psychiatric or endocrine disorders, and being under medication treatment.

Ethics statement

Experiments were approved by the local ethics committee and were conducted in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), and all participants gave their informed written consent to participate in the study. Upon arrival at the lab, participants were assigned a subject ID (VP001, VP002, etc.), which was used throughout the study.

Procedure

Three different sessions were scheduled for each participant, time-locked to their menstrual cycle, in order to study each of the hormonal milieus, as described in61. Therefore, appointments were scheduled (i) during menses (low progesterone and estradiol), (ii) in the pre-ovulatory phase (when estradiol levels peak and progesterone is still low), and (iii) during the mid-luteal phase (high progesterone and estradiol), order counter-balanced. For cycle phase estimation, cycle-length was estimated based on participants self-reports of the onsets of their last three menstrual periods. Since irrespective of cycle length, the duration of the luteal phase is relatively stable around 14 days56, ovulation was estimated to fall 14 days before the onset of next menses. Menses sessions spanned from the first to the seventh day of menstruation (Mday = 3.78, SD = 1.37) depending on the individual cycle length. Pre-ovulatory sessions were scheduled 2–3 days before the expected date of ovulation and confirmed by commercially available urinary ovulation tests (PREGNAFIX) (Mday = 12.26, SD = 2.29). Mid-luteal sessions were scheduled in a window ranging from day 3 post ovulation to 3 days before the onset of the next menstruation (Mday = 21.67, SD = 2.83). Cycle phases were additionally confirmed by salivary hormone levels and participants were excluded if the levels were not as expected for both hormonal values: estradiol not the lowest during menses and progesterone not the highest during luteal phase (see “Hormone analysis” section).

Given that eye blink rate (EBR) is supposed to be stable during daytime, but increases in the evening33, every session took place between 8 am and 5.30 pm. The three sessions of each participant were scheduled approximately at the same time of the day, and time was included as a control variable into the analyses to avoid any confounding effect (see “Statistical analyses” section). Before each session, participants filled in a brief questionnaire concerning food, sports, sleeping habits, and possible ongoing stressors. Spontaneous EBR was recorded as follows. Participants were seated 1 m from a white wall with a black cross at their eyes height and asked to fix their gaze in resting conditions. Vertical and horizontal electro-oculograms (EOGs) were recorded with an EEG system (actiCAP, Brain Products GmbH, Germany) at a sampling rate of 500 Hz and impedances kept under 50 kΩ. Active skin electrodes were placed above the right orbita and at the outer canthi from both eyes, referenced against an electrode below the right orbita, and with a grounding electrode placed on the forehead. Each eye blink was defined as an amplitude wave with a voltage change of 100 µV in a time interval of 500 ms62. The recording lasted six consecutive minutes and the EBR was defined as the average number of blinks per minute. Signals were amplified using an ActiCHamp Amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Germany) and the posterior analysis of the recorded blinks was performed online with Brain Vision Analyzer 2.1 (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany). Two independent observers visually scored the number of blinks for the 6 min segment with an inter-rater reliability of 99% (Cronbach's α > 0.99). After excluding two observations in which the participants blinked at an abnormally high rate (more than 3 SD), EBR ranged from 1.17 to 49.17. Removal of outliers did not produce any substantial changes in the cycle phase effect.

Hormonal analysis

In order to assess estradiol and progesterone levels procedure was followed as described in63. Two saliva samples, each of 2 ml volume, were collected one before and the second after each session and stored in a freezer at − 20 °C immediately after collection. Prior to analysis solid particles were removed by centrifugation (3000 rpm for 15 min, then 3000 rpm for 10 min). Saliva from the two samples was pooled before the analyses to provide a more stable assessment for the average of the hormone levels. Estradiol and progesterone levels were quantified using ELISA kits from DeMediTec Diagnostics, Kiel, Germany. Sensitivity was 0.6 pg/ml for estradiol and 5.0 pg/ml for progesterone. According to the information provided by the manufacturer intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) was between 2.4% and 8.3% for estradiol and between 6.0 and 9.6% for progesterone. Inter-assay CV was between 2.8% and 12.0% for estradiol and between 8.6 and 10.1% for progesterone. All samples were run in duplicates and assessment of samples with more than 25% variation between duplicates was repeated. Hormone values were used to exclude participants with a mismatch between the actual and expected hormonal profile. Due to insufficient sample volume, there were two missing values for the hormone levels. Each missing value belonged to two different participants and neither of them corresponded to the luteal phase.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in R 3.6.2 (https://www.R-project.org/)64 using nlme65 and BayesFactor packages with default non-informative priors66. The variable time of the day ranged from 8.00 am to 5.30 pm, and was converted into a categorical variable by splitting it into four groups, according to the quartiles of the sample (i.e., p25 = 11:50 am, p50 = 1:00 pm, p75 = 2:30 pm). Moreover, for subsequent modeling, metric variables were standardized prior to the respective analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

At first, to explore the menstrual cycle effects on the EBR, a linear mixed model was fitted to the data, using EBR as dependent variable, cycle phase and time of the day as fixed effects, age as a fixed covariate, and participant number (PNr) as random effect, respectively. Formally, this corresponds to the model equation

where Yijkl is the eye blink rate of the l-th observation, μ is the population mean, Pi is the random effect of participant i, Cj is the fixed effect of cycle number (j = 1, 2, 3), and Tk denotes the fixed effect corresponding to time of the day (k = 1, 2, 3, 4). Finally, the age of participant i is denoted by Ai, and εijkl is the residual (or error) term. Our main interest lies on testing the effect of cycle phase, adjusting for the other variables included in the model. An unspecific covariance structure was chosen, thereby allowing for heteroscedasticity and varying correlations between cycle phases. Analogous models, yet with eye blink rate being replaced by estradiol and progesterone, respectively, were used for assessing changes in hormone levels across the menstrual cycle.

We accounted for multiple testing by using the package multcomp67 for conducting all-pairwise comparisons between cycle phases. Moreover, since the sample sizes were somewhat limited, the assumptions of linearity and normality were difficult to assess in a reliable way. Therefore, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis by using the RM function in the MANOVA.RM68 package in R. The underlying model also allows for including within- and between-subject factors, with the only difference compared to the linear mixed model that age had to be dichotomized by applying a median split. We extracted the ANOVA-type (AT) and the Wald-type (WT) permutation test statistics with the corresponding p-values, because these tests are expected to perform well even under violations of the normality assumption69.

In order to further examine the potential impact of cycle phase on EBR, we additionally applied a Bayesian approach, comparing the specific models of interest (i.e., with and without cycle phase). The Bayes factor (BF) quantifies the relative likelihood of the observed data under two competing models. Let H0 denote the null hypothesis (i.e., model without cycle phase), and H1 the alternative hypothesis (model including the cycle phase), respectively. Then, the BF is defined as follows70:

To test the random effect of the participant number (PNr) we compared the full model H1 to a model without participant number H0′, as described in66. When using the BayesFactor package, the number of iterations for Monte Carlo sampling was set to the default value (i.e., 10,000)66.

Results

Overall, the sample consisted of n = 54 women with a mean age of about 24 years. Further descriptive statistics regarding basic variables, the hormone levels and the eye blink rates are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data, hormone levels and eye blink rate during each cycle phase.

| Sample (n = 54) | Age (y.o.) | Cycle length (days) | First session | Cycle day of assesment | Estradiol (pg/ml) | Progesterone (pg/ml) | Eye Blink Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menses | 23.95 0.50 | 28.63 0.31 | 22 | 3.78 0.19 | 2.98 0.15 | 72.51 8.93 | 15.48 1.56 |

| Pre-ovulatory | 20 | 12.26 0.32 | 3.50 0.19 | 93.80 12.12 | 16.14 1.81 | ||

| Luteal | 12 | 21.67 0.40 | 3.69 0.19 | 283.98 33.38 | 16.11 1.59 |

Values are presented as mean standard error of the mean (M SEM) for the final sample of n = 54.

Endocrine results

Estradiol was significantly higher in the pre-ovulatory phase and luteal phase compared to menses (p < 0.001; for details see Tables S1, S2 in the supplement), yet did not differ significantly between pre-ovulatory and luteal phase (p = 0.325). Progesterone was significantly higher in the luteal phase compared to menses and pre-ovulatory phases (p < 0.001; for details see Tables S3, S4 in the supplement), but did not differ significantly between the pre-ovulatory phase and menses (p = 0.130).

Menstrual cycle changes in spontaneous eye blink rate

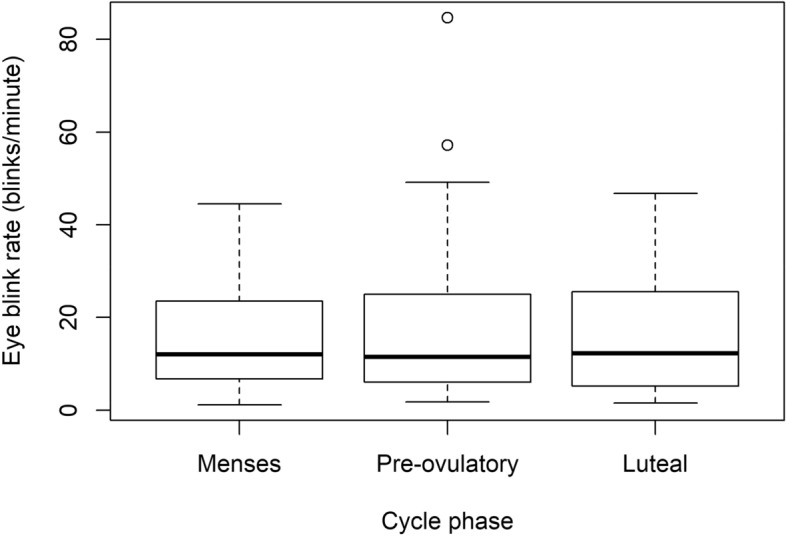

No significant differences in EBR were found across the menstrual cycle, nor changes related to the time of the day or age (Fig. 1, Table 2). The standard deviation corresponding to the random subject effect was equal to 0.856, and the residual standard deviation was 0.4904. Multiple pairwise comparisons between cycle phases revealed that the most pronounced, yet non-significant difference between EBRs occurred between menses and pre-ovulatory phases (Table 3). Moreover, the results from the analysis using the MANOVA.RM package were overall in line with the findings from the linear mixed model, including a non-significant effect of the cycle phase (WTS, p = 0.620 and ATS, p = 0.621). The trend observed for age in the linear mixed model was not corroborated by the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 1.

Bloxplot of the eye blink rate along the menstrual cycle (outliers included): Blinks per minute along the three cycle phases did not change significantly (p = 0.421).

Table 2.

Linear mixed model results for the fixed effects, using eye blink rate as outcome variable.

| Variable | F value | DFn, DFd | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of the day | 0.947 | 3, 101 | 0.421 |

| Age | 4.004 | 1, 52 | 0.051 |

| Cycle phase | 1.080 | 2, 101 | 0.343 |

F value ANOVA test statistic, DFn numerator degrees of freedom, DFd denominator degrees of freedom.

Table 3.

All-pairwise comparisons of eye blink rates between cycle phases.

| Comparison | Mean difference (95% CI) | Test statistic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| P minus M | 0.137 (− 0.082, 0.355) | 1.466 | 0.306 |

| L minus M | 0.060 (− 0.129, 0.249) | 0.741 | 0.738 |

| L minus P | − 0.077 (− 0.267, 0.114) | − 0.944 | 0.611 |

Mean differences and confidence intervals (CI) refer to differences in (standardized) eye blink rates.

M menses, P pre-ovulatory, L luteal.

p values and confidence intervals have been adjusted for multiple comparisons.

In order to quantify the support of a model without cycle phase relative to a model including it (i.e., the “full model”, see “Statistical analyses” section) we applied a Bayesian approach. The resulting Bayes Factor BF01(H0/H1) = 6.410 ± 3.41% again indicated that cycle phase did not play a significant role with respect to eye blink rate, instead providing substantial evidence71 for the model without cycle phase. Finally, in order to corroborate the intra-subject consistency of the EBR (between-session reliability, Cronbach’s α > 0.90), we quantified the support of a model without the participant number relative to a model including it. The resulting BF0′1(H0′/H1) = 9.422 e−27 ± 2.46%, indicated very strong evidence in favor of the random effect of the PNr in the EBR71,72.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore the spontaneous eye blink rate (EBR) across the menstrual cycle. Given that the EBR has been implicated in dopamine-dependent cognitive processes2 and estradiol has been shown to enhance dopamine levels48–52, we hypothesized that EBR would increase during the high estradiol pre-ovulatory cycle phase. Contrary to our expectations, we observed substantial evidence supporting a model without the cycle phase over the model including it71–73. We also provided very strong and decisive support71,72 for the intra-subject consistency of the EBR in women, and thus, we conclude that the fluctuation of endogenous ovarian hormone levels is not reflected on EBR measurements along the menstrual cycle.

Although changes in the EBR depending on women’s hormonal status have been previously reported, like in women on the contraceptive pill41 or postmenopausal women39, the subtle variation of endogenous hormones during the reproductive age does not seem to impact the EBR. Accordingly, we did not find any relation of the EBR measures across the cycle phases to estradiol or progesterone levels. Even when hormonal changes across the menstrual cycle have been linked to different dopamine (DA) baseline levels74,75, the EBR does not seem sensitive to those changes, probably given its high intra-subject consistency. Moreover, the sensitivity of the EBR as a physiological measure for striatal DA levels is still under debate. Although inter-individual variation in the EBR has been consistently linked to dopaminergic functioning2, it remains a highly unspecific, though non-invasive, measure. On one hand, converging evidence from animal and human research attributes the relationship between EBR and DA to the tonic striatal levels and D2 type receptor44,59,76,77, mainly expressed in striatum78. On the other hand, some PET studies in humans did not find a relation between EBR and DA synthesis capacity31 or D2/3-receptor availability30. More recently, in a pharmacological study, Chakroun et al.58 found no modulation of the EBR by L-dopa (DA precursor) and haloperidol (D2 receptor antagonist).

More importantly, the present results do not support the exclusion of female participants when using the EBR. Women continue to form the smaller proportion of subjects in scientific research, and, while in animal research sex and endocrine status is usually controlled, this does not apply to humans. Paradoxically, studies including human and non-human species, controlled for sex in animals, but not in humans19. Despite some inconsistent results6,11,40–42, strong evidence points to higher EBR in women compared to men (see review46), which could reflect the higher extracellular baseline levels of DA in women79. Given these possible sex differences and the impact of sex hormones on the DA system, especially important for DA-dependent neuropsychiatric syndromes80, women should be included in future studies and the factor sex should be taken into account. Although in a previous study we used the EBR during menses as a cautionary measure63, the present results evidence the stability of the EBR also across the menstrual cycle.

Conclusions

In summary, EBR appears to be highly stable within healthy young women and a noisy putative measure for striatal dopaminergic functioning, probably reflecting a trait-like stability more than dynamic changes42,59. The present study shows that a possible effect derived from the endogenous fluctuation of sex hormones can no longer be used as deterrence against including female participants. Therefore, we strongly encourage researchers to include women, regardless of their cycle phase, in future EBR research.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Assoz.-Prof. Wolfgang Trutschnig for his help and assistance during the data analyses. We also thank the students of Belinda Pletzer for their assistance during participant’s recruitment and data acquisition, and the PREGNAFIX ovulation tests company ATT Drogerievertriebs GmbH, for donating ovulation tests. Furthermore, we thank all participants for their time and willingness to contribute to this study.

Author contributions

B.P. designed and made the concept of the study. E.H. was responsible for data acquisition. Analysis and interpretation of the data was performed by E.H. and B.P., and revised by G.Z. E.H. drafted the manuscript, which was revised and approved by B.P. and G.Z. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), PhD Programme “Imaging the Mind: Connectivity and Higher Cognitive Function” [W 1233-G17], and P28261 Single Investigator Project. GZ was supported by the WISS 2025 project 'IDA-Lab Salzburg' (20204-WISS/225/197-2019 and 20102-F1901166-KZP).

Data availability

Data and scripts will be openly available at https://webapps.ccns.sbg.ac.at/OpenData/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Esmeralda Hidalgo-Lopez, Email: esmeralda.hidalgolopez@sbg.ac.at.

Belinda Pletzer, Email: Belinda.Pletzer@sbg.ac.at.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72749-2.

References

- 1.Ostow M, Ostow M. The frequency of blinking in mental illness: A measurable somatic aspect of attitude. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1945;102:294–301. doi: 10.1097/00005053-194509000-00012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckstein MK, Guerra-Carrillo B, Miller Singley AT, Bunge SA. Beyond eye gaze: What else can eyetracking reveal about cognition and cognitive development? Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2017;25:69–91. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreisbach G, et al. Dopamine and cognitive control: The influence of spontaneous eyeblink rate and dopamine gene polymorphisms on perseveration and distractibility. Behav. Neurosci. 2005;119:483–490. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karson CN, Burns RS, LeWitt PA, Foster NL, Newman RP. Blink rates and disorders of movement. Neurology. 1984;34:677–678. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franks CM. Ocular movements and spontaneous blink rate as functions of personality. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1963;16:178. doi: 10.2466/pms.1963.16.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbato G, della Monica C, Costanzo A, De Padova V. Dopamine activation in neuroticism as measured by spontaneous eye blink rate. Physiol. Behav. 2012;105:332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh J, Han M, Peterson BS, Jeong J. Spontaneous eyeblinks are correlated with responses during the stroop task. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Slooten JC, Jahfari S, Knapen T, Theeuwes J. Individual differences in eye blink rate predict both transient and tonic pupil responses during reversal learning. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0185665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Slooten JC, Jahfari S, Theeuwesu J. Spontaneous eye blink rate predicts individual differences in exploration and exploitation during reinforcement learning. BioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/661553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pajkossy P, Szollosi Á, Demeter G, Racsmány M. Physiological measures of dopaminergic and noradrenergic activity during attentional set shifting and reversal. Front. Psychol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang T, et al. Dopamine and executive function: Increased spontaneous eye blink rates correlate with better set-shifting and inhibition, but poorer updating. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015;96:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karson CN. Spontaneous eye-blink rates and dopaminergic systems. Brain. 1983;106:643–653. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens JR. Eye blink and schizophrenia: Psychosis or tardive dyskinesia? Am. J. Psychiatry. 1978;135:223–226. doi: 10.1176/ajp.135.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karson CN, Dykman RA, Paige SR. Blink rates in schizophrenia. Schizoph. Bull. 1990;16:345. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willeit M, et al. In vivo imaging of dopamine metabolism and dopamine transporter function in the human brain. Neuromethods. 2016;118:203–220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3765-3_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor JR, et al. Spontaneous blink rates correlate with dopamine levels in the caudate nucleus of MPTP-treated monkeys. Exp. Neurol. 1999;158:214–220. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korsgaard S, Gerlach J, Christensson E. Behavioral aspects of serotonin-dopamine interaction in the monkey. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;118:245–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elsworth JD, et al. D1 and D2 dopamine receptors independently regulate spontaneous blink rate in the vervet monkey. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;259:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaminer J, Powers AS, Horn KG, Hui C, Evinger C. Characterizing the spontaneous blink generator: An animal model. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11256–11267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6218-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleven MS, Koek W. Differential effects of direct and indirect dopamine agonists on eye blink rate in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1211–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blin O, Masson G, Azulay J, Fondarai J, Serratrice G. Apomorphine-induced blinking and yawning in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1990;30:769–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strakowski SM, Sax KW. Progressive behavioral response to repeated d-amphetamine challenge: Further evidence for sensitization in humans. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;44:1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(97)00454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strakowski S, Sax K, Setters M, Keck P. Enhanced response to repeated d-amphetamine challenge: Evidence for behavioral sensitization in humans. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;40:872. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00497-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korosec M, Zidar I, Reits D, Vanderwerf F, Evinger C. FC101 Reflex blink effects on smooth pursuit maintenance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen EYH, Lam LCW, Chen RYL, Nguyen DGH. Blink rate, neurocognitive impairments, and symptoms in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;40:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung V, Chen EY, Chen RY, Woo MF, Yee BK. A comparison between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls on the expression of attentional blink in a rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) paradigm. Schizophr. Bull. 2002;28:443–458. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen DJ, Detlor J, Young JG, Shaywitz BA. Clonidine ameliorates Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1980;37:1350–1357. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780250036004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowal MA, Colzato LS, Hommel B. Decreased spontaneous eye blink rates in chronic cannabis users: Evidence for striatal cannabinoid-dopamine interactions. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathar D, Wiehler A, Chakroun K, Goltz D, Peters J. A potential link between gambling addiction severity and central dopamine levels: Evidence from spontaneous eye blink rates. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13371. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31531-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dang LC, et al. Spontaneous eye blink rate (EBR) is uncorrelated with dopamine D2 receptor availability and unmodulated by dopamine agonism in healthy adults. eNeuro. 2017 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0211-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sescousse G, et al. Spontaneous eye blink rate and dopamine synthesis capacity: Preliminary evidence for an absence of positive correlation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018;47:1081–1086. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano T. The right angular gyrus controls spontaneous eyeblink rate: A combined structural MRI and TMS study. Cortex. 2017;88:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbato G, et al. Diurnal variation in spontaneous eye-blink rate. Psychiatry Res. 2000;93:145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbato G, Cirace F, Monteforte E, Costanzo A. Seasonal variation of spontaneous blink rate and beta EEG activity. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fogarty C, Stern JA. Eye movements and blinks: Their relationship to higher cognitive processes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1989;8:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-8760(89)90017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zametkin AJ, Stevens JR, Pittman R. Ontogeny of spontaneous blinking and of habituation of the blink reflex. Ann. Neurol. 1979;5:453–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.410050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruz AAV, Garcia DM, Pinto CT, Cechetti SP. Spontaneous eyeblink activity. Ocular Surf. 2011;9:29–41. doi: 10.1016/S1542-0124(11)70007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacher LF. Development and manipulation of spontaneous eye blinking in the first year: Relationships to context and positive affect. Dev. Psychobiol. 2014;56:783–796. doi: 10.1002/dev.21148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen WH, Chiang TJ, Hsu MC, Liu JS. The validity of eye blink rate in Chinese adults for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2003;105:90–92. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(02)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berenbaum H, Williams M. Extraversion, hemispatial bias, and eyeblink rates. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1994;17:849–852. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(94)90052-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yolton DP, et al. The effects of gender and birth control pill use on spontaneous blink rates. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1994;65:763–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kruis A, Slagter HA, Bachhuber DRW, Davidson RJ, Lutz A. Effects of meditation practice on spontaneous eyeblink rate. Psychophysiology. 2016 doi: 10.1111/psyp.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Müller J, et al. Dopamine and cognitive control: The prospect of monetary gains influences the balance between flexibility and stability in a set-shifting paradigm. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:3661–3668. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hua JPY, Kerns JG. Differentiating positive schizotypy and mania risk scales and their associations with spontaneous eye blink rate. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bentivoglio AR, et al. Analysis of blink rate patterns in normal subjects. Mov. Disord. 1997;12:1028–1034. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jongkees BJ, Colzato LS. Spontaneous eye blink rate as predictor of dopamine-related cognitive function—A review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;71:58–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoest KE, Quigley JA, Becker JB. Rapid effects of ovarian hormones in dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens. Horm. Behav. 2018;104:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becker JB. Direct effect of 17β-estradiol on striatum: Sex differences in dopamine release. Synapse. 1990;5:157–164. doi: 10.1002/syn.890050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bazzett TJ, Becker JB. Sex differences in the rapid and acute effects of estrogen on striatal D2dopamine receptor binding. Brain Res. 1994;637:163–172. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker JB. Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1999;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker JB, Rudick CN. Rapid effects of estrogen or progesterone on the amphetamine-induced increase in striatal dopamine are enhanced by estrogen priming: A microdialysis study. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1999;64:53–57. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00091-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tansey EM, Arbuthnott GW, Fink G, Whale D. Oestradiol-17β increases the firing rate of antidromically identified neurones of the rat neostriatum. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;37:106–110. doi: 10.1159/000123527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun J, Walker AJ, Dean B, van den Buuse M, Gogos A. Progesterone: The neglected hormone in schizophrenia? A focus on progesterone-dopamine interactions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;74:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cabrera R, Díaz A, Pinter A, Belmar J. In vitro progesterone effects on 3H-dopamine release from rat corpus striatum slices obtained under different endocrine conditions. Life Sci. 1993;53:1767–1777. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90164-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dluzen DE, Ramirez VD. Intermittent infusion of progesterone potentiates whereas continuous infusion reduces amphetamine-stimulated dopamine release from ovariectomized estrogen-primed rat striatal fragments superfused in vitro. Brain Res. 1987;406:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90762-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fehring RJ, Schneider M, Raviele K. Variability in the phases of the menstrual cycle. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:376–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doughty MJ, Naase T, Button NF. Frequent spontaneous eyeblink activity associated with reduced conjunctival surface (trigeminal nerve) tactile sensitivity. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009;247:939–946. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-1028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chakroun K, Mathar D, Wiehler A, Ganzer F, Peters J. Dopaminergic modulation of the exploration/exploitation trade-off in human decision-making. BioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/706176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Groman SM, et al. In the blink of an eye: Relating positive-feedback sensitivity to striatal dopamine d2-like receptors through blink rate. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:14443–14454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3037-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee SJ, Lenton EA, Sexton L, Cooke ID. The effect of age on the cyclical patterns of plasma LH, FSH, oestradiol and progesterone in women with regular menstrual cycles. Hum. Reprod. 1988 doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hidalgo-Lopez E, Pletzer B. Individual differences in the effect of menstrual cycle on basal ganglia inhibitory control. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:11063. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47426-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colzato LS, Van Den Wildenberg WPM, Van Wouwe NC, Pannebakker MM, Hommel B. Dopamine and inhibitory action control: Evidence from spontaneous eye blink rates. Exp. Brain Res. 2009;196:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1862-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hidalgo-Lopez E, Pletzer B. Interactive effects of dopamine baseline levels and cycle phase on executive functions: The role of Progesterone. Front. Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2018). Accessed 27 Sept 2019.

- 65.Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. R Core Team. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–148. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (2020). Accessed 27 Sept 2019.

- 66.Morey, R. D., Rouder, J. N. & Jamil, T. Package ‘ BayesFactor ’. BayesFactor: Computation of Bayes Factors for Common Designs. R package version 0.9.12–4.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=BayesFactor (2018). Accessed 27 Sept 2019.

- 67.Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometr. J. 2008 doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Friedrich, S., Konietschke, F. & Pauly, M. MANOVA.RM: Analysis of multivariate data and repeated measures designs. R package version 0.3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MANOVA.RM. (2018). Accessed 27 Sept 2019.

- 69.Friedrich S, Brunner E, Pauly M. Permuting longitudinal data in spite of the dependencies. J. Multivar. Anal. 2017;153:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmva.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jarosz AF, Wiley J. What are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting bayes factors. J. Probl. Solving. 2014;7:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995 doi: 10.2307/2291091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jeffreys H. Theory of Probability. Oxford: Clarendon; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dienes Z. Using Bayes to get the most out of non-significant results. Front. Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colzato LS, Hommel B. Effects of estrogen on higher-order cognitive functions in unstressed human females may depend on individual variation in dopamine baseline levels. Front. Neurosci. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobs E, D’Esposito M. Estrogen shapes dopamine-dependent cognitive processes: Implications for women’s health. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:5286–5293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6394-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Slagter HA, Georgopoulou K, Frank MJ. Spontaneous eye blink rate predicts learning from negative, but not positive, outcomes. Neuropsychologia. 2015;71:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Slooten JC, Jahfari S, Knapen T, Theeuwes J. How pupil responses track value-based decision-making during and after reinforcement learning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63:182–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Riccardi P, et al. Sex differences in the relationship of regional dopamine release to affect and cognitive function in striatal and extrastriatal regions using positron emission tomography and [18F]fallypride. Synapse. 2011 doi: 10.1002/syn.20822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hartung CM, Widiger TA. Gender differences in the diagnosis of mental disorders: Conclusions and controversies of the DSM-IV. Psychol. Bull. 1998;123:260–278. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and scripts will be openly available at https://webapps.ccns.sbg.ac.at/OpenData/.