Abstract

The etiology of CNS diseases including multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis remains elusive despite decades of research resulting in treatments with only symptomatic effects. In this study, we provide evidence that a metabolic shift from glucose to lipid is a key mechanism in neurodegeneration. We show that, by downregulating the metabolism of lipids through the key molecule carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1), it is possible to reverse or slowdown disease progression in experimental models of autoimmune encephalomyelitis-, SOD1G93A and rotenone models, mimicking these CNS diseases in humans. The effect was seen both when applying a CPT1 blocker or by using a Cpt1a P479L mutant mouse strain. Furthermore, we show that diet, epigenetics, and microbiota are key elements in this metabolic shift. Finally, we present a systemic model for understanding the complex etiology of neurodegeneration and how different regulatory systems are interconnected through a central metabolic pathway that becomes deregulated under specific conditions.

Subject terms: Demyelinating diseases, Motor neuron disease, Neurodegenerative diseases, Experimental models of disease, Preclinical research, Drug development

Introduction

In the last decades, the incidence of central nervous system (CNS) diseases including multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) have been increasing1–3. CNS diseases, specifically neurodegenerative diseases, have a pronounced impact on the patient’s quality of life and represent a major economic and emotional burden to both close relatives and society at large. The etiology and pathogenesis of CNS diseases remain elusive. Consequently, few treatment options exist, and no cure is yet available for those aforementioned CNS disorders. Treatments are mainly limited to partial symptomatic relief, but progression and the long-term outcome often remain unimproved.

Though seemingly individual conditions, several CNS diseases share common etiological and pathological pathways involved in onset and progression such as inflammation, oxidative stress, demyelination, dysbiosis in the gut and changes in metabolism1,3–5. Moreover, we know that increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), triglycerides and total cholesterol levels, and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol are also associated with disease progression6–8. Thus, we propose a novel perspective for looking at MS, ALS and PD pathogenesis through a systemic perspective with focus on the role of dysregulated metabolism in these conditions. In MS, several mechanisms of immunoreactivity have been proposed such as molecular mimicry, bystander activation, and altered peptide ligand1. However, studies indicate that upregulated lipid metabolism, and changes in the lipid binding protein of myelin could be the trigger of disease leading to the activation, and ultimately dysregulation, of the immune system9–11. The activation of immune cells such as microglia, can lead to the production of reactive oxygen species, and thereby oxidative stress12,13. Moreover, a shift to lipid metabolism has been found to drive activity of immune cells and inflammation14,15. In PD, several mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration such as mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress are linked to the metabolism of lipids16. Furthermore, PD patients have lower serum levels of lipids, which indicates a potential role of metabolic alterations in disease onset, since a higher level of lipids in serum has been found associated with a low prevalence of PD6. In ALS, various disease mechanisms causing irreversible damage to motor neurons such as endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and glutamate excitotoxicity have also been suggested17. A higher level of triglycerides have been associated with longer survival rates in ALS patients18. In accordance, ALS-mouse models revealed that a decrease in lipids level could lead to disease progression and that lipid metabolism is upregulated prior to disease8,19,20. Based on this evidence, our approach is to investigate neurodegenerative, pathological changes in lipid metabolism using in vivo models of MS, ALS, and PD. Specifically, we aimed at investigating the role of a key mitochondrial molecule, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1), involved in the regulation of both lipids and glucose, and how its activity in the CNS could impact disease development and progression.

To maintain the homeostasis of energy in the brain, a balance between the oxidation of glucose and that of fatty acids is required21. Fatty acid oxidation occurs through the uptake of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA), facilitated by fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs)22. Following the uptake, LCFA are converted to acyl-CoA by the acyl-CoA synthase activity of the FATPs21. Due to the impermeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane to fatty acyl-CoA, a carnitine shuttle, CPT1, is needed to convert acyl-CoA into acyl-carnitine. This is followed by the second step within the inner mitochondrial membrane, where CPT2 reconverts acyl-carnitine into acyl-CoA and carnitine21. This underpins the clear-cut function of the mitochondria, and specifically CPT1 and CPT2, to permit β-oxidation of fatty acids, which is necessary for the production of acetyl-CoA used in ATP production by the Krebs cycle21,23.

Energy metabolism is crucial to cell and organ function, but metabolic pathways have often been overlooked in studies relating to CNS injuries and diseases. We designed a series of experiments to understand how dysfunctions in metabolic pathways are involved in the progression, etiology, and onset of neurodegeneration with a focus on MS, ALS, and PD. Here, we present evidence of common pathogeneses and consequently provide a target to act on disease modifying mechanisms in addition to control of symptoms. We hypothesize that metabolic dysregulation is the basis for development and progression of several CNS diseases, specifically those leading to neurodegeneration. Specifically, we propose that the dysregulation is—to some degree—a consequence of a shift from glucose to lipid metabolism, which affects several pathways involved in the etiology and progression of CNS diseases. This metabolic shift can be a consequence of several factors: genetic predisposition, environmental factors or most likely, a combination of both. In this study, we have tested our hypothesis by pharmacologically blocking CPT1 with the antagonist, etomoxir, and genetically by producing a rodent model with a Cpt1a mutation. The mutation mimics a known human mutation found in the Inuit population, shown to lower the efficiency of CPT1A from 100 to 22%. This study provides further evidence on the role of metabolic alterations and the effect of targeting CPT1 in MS, ALS, and PD through in vivo studies.

Results

Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CPT1 ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induction and symptoms

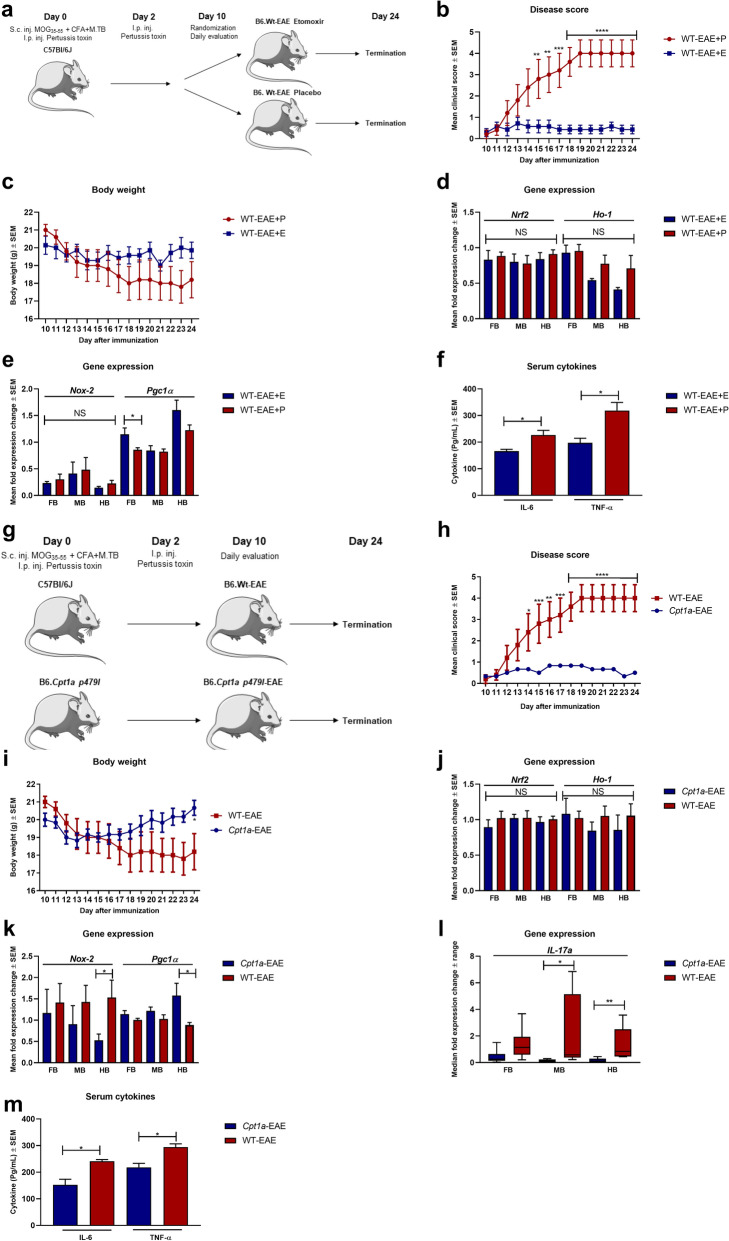

An increased expression of CPT1A has been demonstrated in MS patients and EAE models24,25. Consequently, the effect of pharmacological inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir was evaluated in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) animal model of MS (Fig. 1a). Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein35–55 (MOG35–55) immunized C57bl/6J female mice receiving etomoxir (WT-EAE + E) (n = 7) showed a significant decreased mean clinical score compared to the mice receiving placebo treatment (WT-EAE + P) (n = 5) (Fig. 1b) and no decrease in body weight (Fig. 1c). Following the animal experiments, we conducted RT-qPCR to evaluate whether etomoxir changed the gene expression of markers of oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in the fore-, mid-, and hindbrain. Interestingly, we found that etomoxir-treated mice had a tendency towards lower gene expression of Ho-1 and Nox-2 in the brain (Fig. 1d,e), although it did not reach statistical significance. However, etomoxir-treated mice had statistical higher expression of Pgc1α (Fig. 1e) in the forebrain, indicating amelioration of mitochondrial dysfunction at least in some parts of the brain. To evaluate whether etomoxir treatment had affected the inflammatory response, we evaluated serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-α and found that etomoxir-treated mice had significantly lower levels of both cytokines (Fig. 1f). This indicates that downregulation of CPT1 lipid metabolism affects several key processes in the disease progression of EAE.

Figure 1.

The efficacy of pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CPT1 in EAE models of MS. (a) Experimental setup for the EAE-etomoxir study in female C57Bl/6J mice. (b) Disease score of WT-EAE-E (n = 7) and WT-EAE (n = 5) mice. (c) Body weight of WT-EAE-E (n = 7) and WT-EAE (n = 5) mice. (d) Mean fold gene expression change of IL-17α in FB, MB and HB of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice at day 24. (e) Mean fold gene expression change of Nrf2 and Ho-1 in FB, MB and HB of WT-EAE-E (n = 7) and WT-EAE-P (n = 5) mice at day 24. (f) Cytokine level of IL-6 and TNF-α in serum of WT-EAE-E (n = 3) and WT-EAE-P (n = 3) mice at day 24. (g) Experimental setup for the Cpt1a-EAE study comparing Cpt1a-mutant mice with C57Bl/6J female mice. (h) Disease score of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice from day 10. (i) Body weight of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice from day 10. (j) Mean fold gene expression change of Nrf2 and Ho-1 in FB, MB and HB of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice at day 24. (k) Mean fold gene expression change Nox-2 and Pgc1α1 in FB, MB and HB of WT-EAE-E (n = 7) and WT-EAE-P (n = 5) mice at day 24. (l) Mean fold gene expression change of Nox-2 and Pgc1α1 in FB, MB and HB of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice at day 24. (m) Cytokine level of IL-6 and TNF-α in serum of WT-EAE (n = 3) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 4) mice at day 24. Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Abbreviations: Cpt1a, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a with a p479l mutation; E, etomoxir; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; WT, wild type; FB, forebrain; MB, midbrain; HB, hindbrain; MOG, Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein35–55 (MOG35–55), CFA, Complete Freund's Adjuvant; S.c., Subcutaneous; I.p., Intraperitoneal; Inj., Injection; SEM: standard error of the mean. We acknowledge Servier Medical Art for the mouse illustration, which can be found at: https://smart.servier.com/ with the following license; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. No changes were made to the drawing.

To further assess the contribution of CPT1A in the development of EAE, we generated Cpt1a-mutated mice26 and compared these with WT mice. Both WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) female mice were immunized with MOG35–55 (Fig. 1g). The results showed that the WT-EAE mice presented worsening of mean clinical scores of up to 4, compared to the Cpt1a-EAE mice with a mean clinical score of 0.5. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant from day 14 of the experiment and onwards (Fig. 1h). The body weight was also used as a hallmark to evaluate the effect of EAE immunization. The body weight in the group of WT-EAE mice (n = 5) decreased from day 10 to day 24, and was significantly different from the body weight of the Cpt1a-EAE mice (n = 6) at the last day of the experiment (Fig. 1i). Based on the clinical effects, we evaluated whether the Cpt1a-mutation changed gene expression of markers of oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and inflammation in the fore-, mid-, and hindbrain of both WT-EAE and Cpt1a-EAE mice. The Cpt1a-EAE group had lower expression of Ho-1, and significantly lower expression of Nox-2 in the hindbrain (Fig. 1j–k). This indicated that the Cpt1a mutation affected oxidative stress. Moreover, the Cpt1a-EAE group had significantly higher expression of Pcg1α in the hindbrain (Fig. 1k) indicating that the downregulation of CPT1A lipid metabolism resulted in amelioration of mitochondrial dysfunction. The Cpt1a-EAE group had significantly lower IL-17α expression in the mid-, and hindbrain (Fig. 1l). This was consistent with lower serum levels of IL-6 and TNF- α in serum compared to WT-EAE mice (Fig. 1m). This indicated that downregulation of CPT1A activity was able to diminish inflammation.

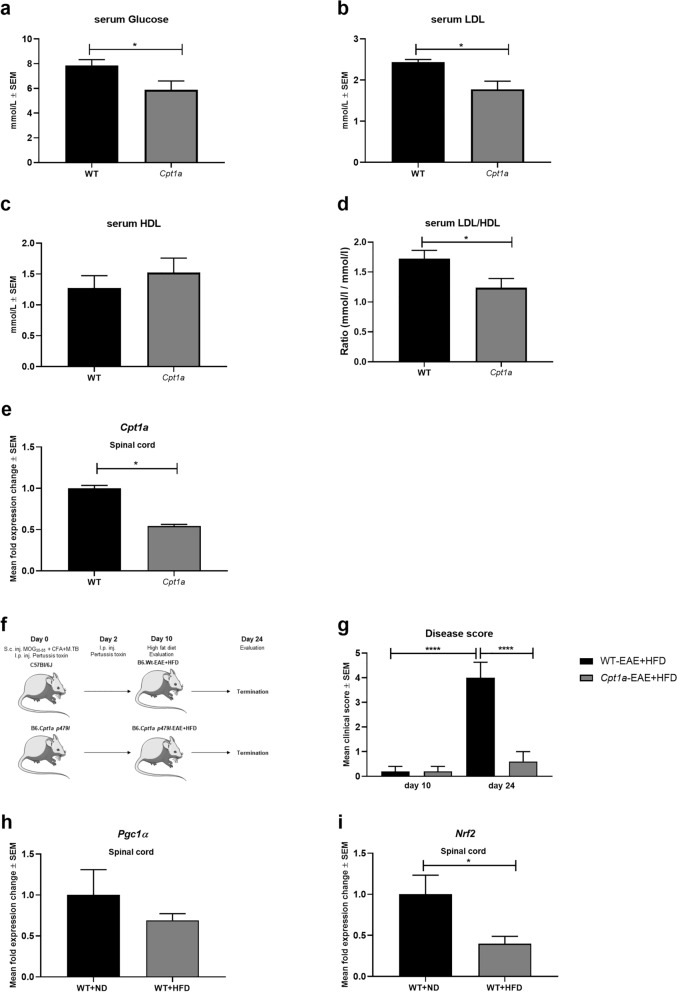

Cpt1a mutation provides resistance to high fat diet accelerated EAE induction and symptoms

The Cpt1a-mutated mouse model resembles the human CPT1A mutation found in the Inuit population living in Canada and Greenland. The CPT1A nucleotide mutation located at position 1436 C > T predicting a substitution of proline to leucine at codon 479 (P479L)27 resulting in a residual activity of 22% of the CPT1A protein28. In accordance with this, we have found that Cpt1a-mutated mice have changes in glucose, LDL and HDL levels (Fig. 2a–d) and that Cpt1a-mutated mice have decreased Cpt1a expression in the spinal cord (Fig. 2e). High-fat diet (HFD) is associated with increased disease severity of both MS and EAE by changes in metabolism, inflammation and oxidative stress26. Specifically HFD has been found to upregulate CPT1A lipid metabolism29. Therefore, we investigated the effect of HFD in the EAE model using female Cpt1a and WT mice (Fig. 2f). The results showed that the mean clinical scores of the WT-EAE + HFD female mice (n = 5) increased significantly from day 10, at which the mice were subjected to the HFD, until day 24. Additionally, the mean clinical scores were significantly lower for the Cpt1a-EAE + HFD mice (n = 6) at day 24 compared to WT-EAE + HFD (Fig. 2g). Interestingly, we have found that female WT mice receiving HFD for 10 weeks have decreased expression of Nrf2 and Pgc1α in the spinal cord compared to WT + ND mice (Fig. 2h–i). The data of low disease induction in the Cpt1a-EAE mice found in this study (Fig. 2c–e) support the findings of low prevalence of MS in this northern indigenous population compared to the non-indigenous population in Canada30,31.

Figure 2.

Cpt1a-mutated mice have changes in serum metabolites and high fat diet affects disease progression in EAE mouse model, and gene expression in spinal cord. (a) Glucose level in serum from Cpt1a-mutated male mice (n = 12) and WT mice (n = 15). (b) LDL level in serum from Cpt1a-mutated male mice (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 5). (c) HDL level in serum from Cpt1a-mutated male mice (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 5). (d) LDL/HDL ratio in serum from Cpt1a-mutated male mice (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 5). (e) Mean fold gene expression change of Cpt1a in spinal cord of female WT- (n = 3) and Cpt1a-mutated mice (n = 3). (f) Experimental setup for the high fat diet Cpt1a-EAE and WT-EAE study comparing the effect of HFD on EAE disease progression. (g) Efficacy of high-fat diet on EAE disease severity of WT-EAE (n = 5) and Cpt1a-EAE (n = 6) mice from day 10 to day 24. (h) Mean fold gene expression change of Pgc1α in spinal cord of female WT- (n = 3) and Cpt1a-mutated mice (n = 3). (i) Mean fold gene expression change of Nrf2 in spinal cord of female WT-ND (n = 4) and WT-HFD mice (n = 4). Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (*p < 0.05). Abbreviations: Cpt1a, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a with a p479l mutation; ND, normal diet, HFD, high fat diet. E, etomoxir; P, placebo; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; MOG, Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein35–55 (MOG35–55), CFA, Complete Freund's Adjuvant; S.c., Subcutaneous; I.p., Intraperitoneal; Inj., Injection; WT, wild type. SEM: standard error of the mean. We acknowledge Servier Medical Art for the mouse illustration, which can be found at: https://smart.servier.com/. License; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. No changes were made to the drawing.

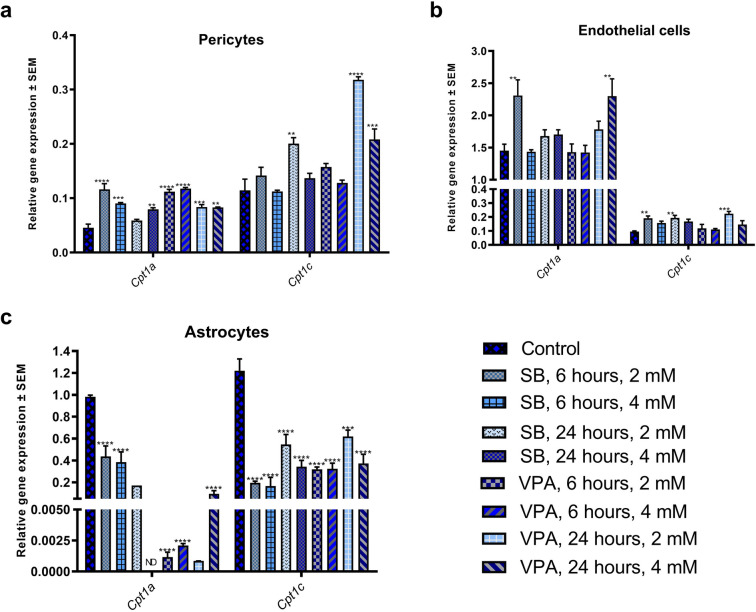

Cpt1a is epigenetically regulated in the rat blood brain barrier

Cpt1a gene is a key regulator of long chain fatty acids metabolism. The transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the Cpt1a in every living organism facilitate adaptation to the changing environment, especially to diet. Recently, Moody et al. provided evidence for epigenetic regulation of Cpt1a by DNA methylation and histone modifications in liver of rats fed HFD32. The human study of blood samples from the great Dutch famine also showed regulation of Cpt1a by DNA methylation33. The Blood Brain Barrier (BBB) is the tight epithelium regulating the influx of, among others, metabolites into the brain. Therefore, we used primary BBB-associated cells (endothelium, astrocytes, pericytes) obtained from rats to investigate the effect of two histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), valproic acid (VPA) and sodium butyrate (SB), on the expression of Cpt1a gene. Cpt1a exhibited significant expression changes in response to both HDACi in the pericytes (Fig. 3a), endothelium (Fig. 3b), and astrocytes (Fig. 3c). As expected, both HDACi led to the increased expression of the Cpt1a in pericytes and endothelial cells through augmented histone acetylation. Unexpectedly, expression of Cpt1a almost disappeared in the astrocytes. More investigation of the role of histone acetylation levels must be done to understand the precise mechanism of HDACi effect on the Cpt1a promoter.

Figure 3.

Expression of Cpt1a and Cpt1c in primary rat BBB-associated cells following treatment with VPA and SB. (a) Relative gene expression of Cpt1a and Cpt1c in pericytes following treatment with VPA and SB. (b) Relative gene expression of Cpt1a and Cpt1c in endothelial cells following treatment with VPA and SB. (c) Relative gene expression of Cpt1a and Cpt1c in astrocytes following treatment with VPA and SB. Data expressed as relative expression to reference genes β-actin and Hprt1 ± SEM. Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Abbreviations: SB, sodium butyrate; VPA, valproic acid. SEM: standard error of the mean.

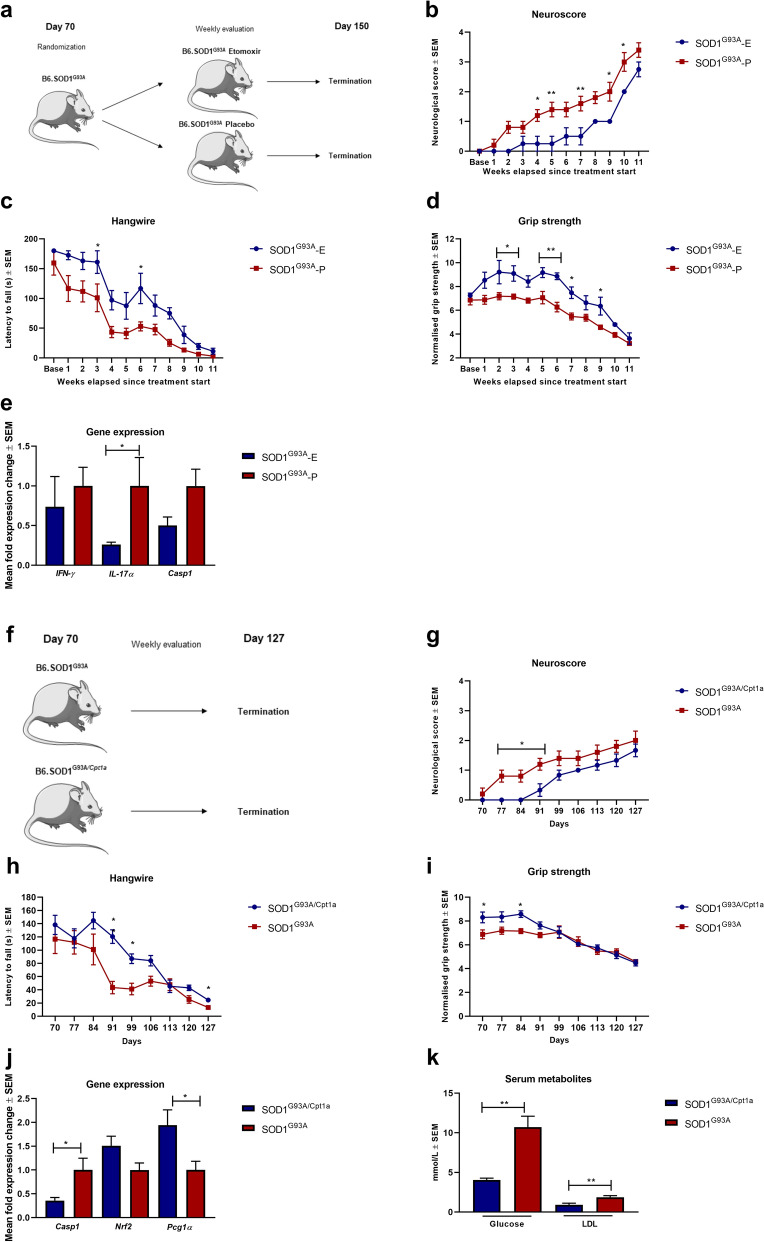

Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CPT1 downregulates disease progression in SOD1G93A mice reflected on neurological scores and gene expression

Several studies have shown that both ALS patients and animal models mimicking ALS have a dysregulated metabolism of lipids19,34. CPT1A and CPT1B are upregulated in the SOD1 mouse model mimicking familial ALS20,35. Therefore, we tested the effect of pharmacological inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir in the SOD1G93A model. The SOD1G93A female mice (n = 9) were randomized into treatment with either etomoxir (5 mg/kg) (n = 4) or placebo (olive oil) (n = 5) from day 70 (baseline) (Fig. 4a). The SOD1G93A mice receiving etomoxir (SOD1G93A-E) showed significantly lower mean neurological score, increased grip strength, and higher latency to fall on the hangwire test compared to mice treated with placebo (SOD1G93A-P) (Fig. 4b–d). Following the SOD1G93A etomoxir experiment, we assessed gene expression in the lumbar spinal cord of the animals to evaluate whether the downregulation of CPT1 affected inflammatory markers. We found that etomoxir-treated SOD1G93A mice had a tendency towards lower expression of Ifn-ϒ, Casp1, and significant lower expression of IL-17α (Fig. 4e). This indicated that downregulation of CPT1 reduces inflammation. These findings support previously presented data that dysregulated metabolism is most likely associated with ALS36.

Figure 4.

The efficacy of pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CPT1 in SOD1G93A model of ALS. (a) Experimental setup for the SOD1G93A-etomoxir study using female mice. (b) Neuroscore of female SOD1G93A-E (n = 4) and SOD1G93A-P (n = 5) mice. (c) Latency to fall on the hang-wire test of female SOD1G93A-E (n = 4) and SOD1G93A-P (n = 5) mice. (d) Normalized grip strength of female SOD1G93A-E (n = 4) and SOD1G93A-P (n = 5) mice. (e) Mean fold expression change of Ifn-ϒ, Il-17α and Casp1 in spinal cord of SOD1G93A-E and SOD1G93A-P mice (n = 3–4). (f) Experimental setup for the SOD1G93A/Cpt1a study comparing heterozygote Cpt1a mutation with SOD1G93A female mice without mutation. (g) Neuroscore of SOD1G93A (n = 5) and SOD1G93A/Cpt1a (n = 6) mice. (h) Latency to fall on the hangwire test of SOD1G93A (n = 5) and SOD1G93A/Cpt1a (n = 6) mice. (i) Normalized grip strength of SOD1G93A (n = 5) and SOD1G93A/Cpt1a (n = 6) mice. (j) Mean fold expression change of Casp1, Nrf2 and Pgc1α in spinal cord of SOD1G93A and SOD1G93A/Cpt1a (n = 3–4). (k) Level of glucose and LDL in serum SOD1G93A and SOD1G93A/Cpt1a (n = 4) mice. Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Abbreviations: SOD1G93A, superoxide dismutase 1 glycine 93 changed to alanine; Cpt1a, heterozygote carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a with a p479l mutation; E, etomoxir; P, placebo. ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. SEM: standard error of the mean. We acknowledge Servier Medical Art for the mouse illustration, which can be found at: https://smart.servier.com/ with the following license; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. No changes were made to the drawing.

To assess the role of CPT1A in the development and progression of ALS, we generated a SOD1G93A mouse model with a heterozygote Cpt1a P479L mutation (SOD1G93A/Cpt1a) with 66% CPT1A activity compared to the wildtype CPT1A (Fig. 4f). The development and progression of disease in the female SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice (n = 6) were compared to SOD1G93A mice (n = 5) from day 70. The SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice had a significantly lower disease score, higher normalized grip strength and a higher latency to fall on the hang-wire test compared to SOD1G93A mice in the early symptomatic stage of the disease but not later (Fig. 4g–i). Following termination of the animal experiments, we assessed changes in gene expression in the lumbar spinal cord to evaluate inflammation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial functioning. We found that SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice had significantly lower Casp1 expression, higher Nrf2 and significantly higher Pgc1α expression (Fig. 4j). This indicates that SOD1G93A/Cpt1a had lower inflammation, better oxidative stress defense and mitochondrial biogenesis. Further, we assessed the levels of glucose and LDL in the serum of SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice and compared these to SOD1G93A mice to assess whether the Cpt1a mutation affected the metabolism. Interestingly, we found that SOD1G93A/Cpt1a had significantly lower levels of glucose and LDL (Fig. 4k). This indicates that CPT1A lipid metabolism plays a role in the development and progression of the disease.

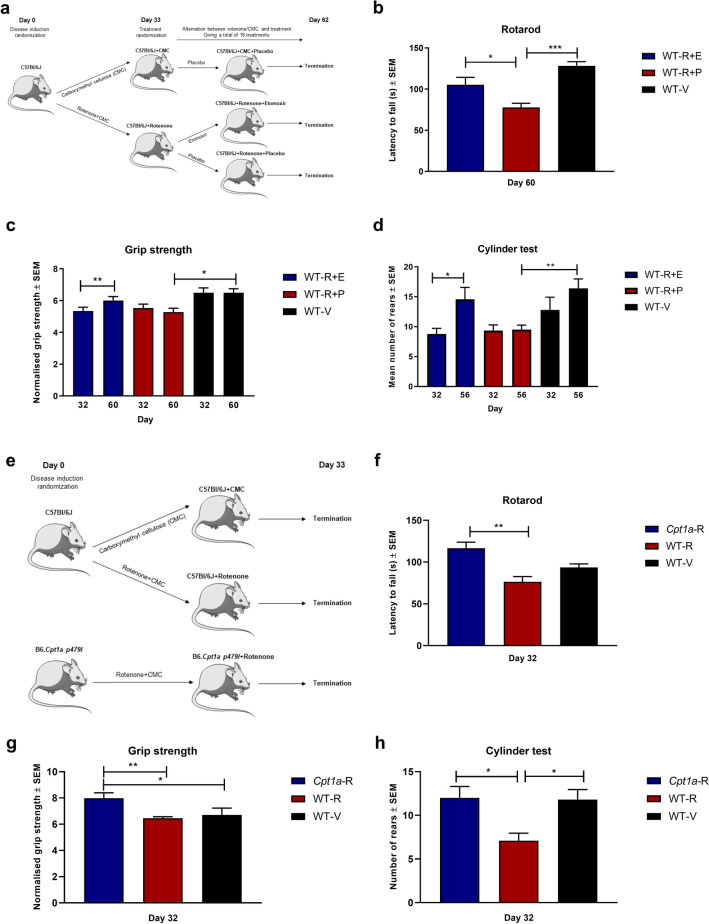

Inhibition of CPT1 and CPT1A reverses disease progression in a chronic rotenone animal model mimicking Parkinson’s disease

Metabolic dysregulation was shown in several studies in both PD patients and animal models of PD (toxic and genetic)6,37. Furthermore, studies have found that β-oxidation is upregulated in PD patients38,39. Rotenone is a pesticide which blocks the mitochondrial complex 1 and has been shown to upregulate CPT1. Therefore, the effect of pharmacological inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir was evaluated in a chronic rotenone mouse model using C57Bl/6J male mice (Fig. 5a). Mice were randomized into a rotenone regimen (30 mg/kg daily, n = 20) or vehicle (0.5% Carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt; CMC, n = 5) for 32 days. The vehicle group served as healthy controls. At day 32, the mice were evaluated for symptoms. Two mice did not develop symptoms of PD, and was removed before initiation of treatment. The rotenone-induced mice were randomized into treatment with etomoxir (5 mg/kg, WT-R + E, n = 9) or placebo (olive oil, WT-R + P, n = 9) (Fig. 5a). The mice receiving CMC were treated with placebo (WT-V). The mice received 18 days of treatment over a period of 30 days (Fig. 5a). The WT-R + E mice had a significantly higher latency to fall on the rotarod compared to WT-R-P mice at day 60 (Fig. 5b). Moreover, etomoxir-treated mice had a significant increase in normalized grip strength compared to day 32 (Fig. 5c) and sensorimotor function in the cylinder test (Fig. 5d). These findings indicate that inhibition of CPT1 could restore motor- and sensorimotor function in the rotenone-induced PD-like C57Bl/6J mouse model.

Figure 5.

The efficacy of pharmacological and genetic inhibition of CPT1 in rotenone models of PD. (a) Experimental setup for the chronic rotenone mouse model treated with etomoxir using male C57Bl/6J mice. (b) Latency to fall of the rotarod at day 60 for WT-R-E (n = 9), WT-R-P (n = 9) and WT-V (n = 5). (c) Normalized grip strength for WT-R-E (n = 9), WT-R-P (n = 9) and WT-V (n = 5) at day 32 before treatment and at day 60. (d) Number of rears in the cylinder test for WT-R-E (n = 9), WT-R-P (n = 6) and WT-V (n = 5) at day 32 before treatment and at day 56. (e) Experimental setup for the chronic rotenone mouse model using Cpt1a-mutated mice and male C57Bl/6J mice. (f) Latency to fall of the rotarod at day 32 for Cpt1a-R (n = 7), WT-R-P (n = 10) and WT-V (n = 5). (g) Normalized grip strength at day 32 for Cpt1a-R (n = 7), WT-R-P (n = 10) and WT-V (n = 5). (h) Number of rears in the cylinder test at day 32 for Cpt1a-R (n = 5), WT-R-P (n = 10) and WT-V (n = 5). Asterisks indicate the level of statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Abbreviations: Cpt1a, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a with a p479l mutation; R, rotenone; E, etomoxir; P, placebo; V, vehicle; WT, wild type. PD: Parkinson’s’ Disease. SEM: standard error of the mean. We acknowledge Servier Medical Art for the mouse illustration, which can be found at: https://smart.servier.com/ with the following license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. No changes were made to the drawing.

To investigate whether CPT1A activity contributed to development of PD, we compared the Cpt1a-mutated male mice with WT male mice for sensitivity to chronic rotenone induced disease (Fig. 5e). Cpt1a-mutated mice (Cpt1a-R, n = 7) and wildtype C57Bl/6J mice (WT-R, n = 10) received rotenone for 32 days (Fig. 5e). Further, wildtype C57Bl/6J mice received treatment with vehicle (WT-v, n = 5) for 32 days. The vehicle group served as healthy controls. At day 32, Cpt1a-R mice had a significantly higher latency to fall on the rotarod (Fig. 5f), a significantly higher normalized grip strength (Fig. 5g), and a significantly higher sensorimotor function in the cylinder test (Fig. 5h) compared to WT-R mice. This finding highlights that Cpt1a-mutated mice, which have a down-regulated lipid metabolism, were resistant to rotenone-induced PD. However, more mechanistic studies are warranted.

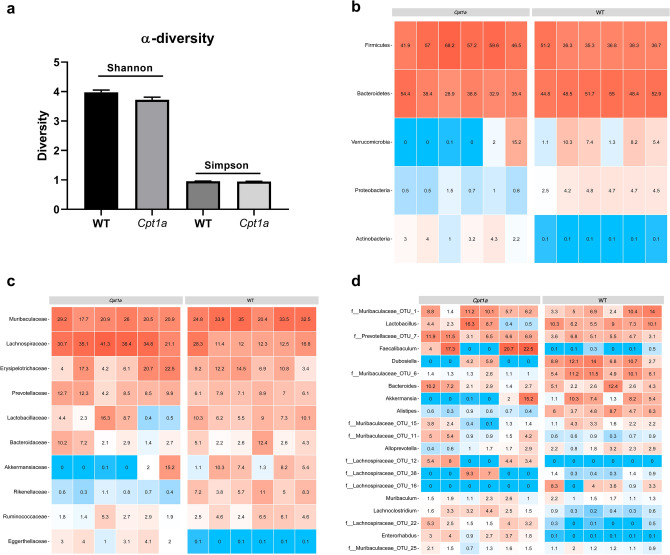

Cpt1a-mutated mice have alternations in the gut microbiome

The role of gut microbiota in the development and progression of CNS diseases has been intensively studied in the last decade40. Based on our findings in the EAE (Fig. 1), SOD1G93A (Fig. 4) and chronic rotenone mouse models (Fig. 5), were Cpt1a-mutated mice showed resistance towards disease induction- and progression. We hypothesized that the Cpt1a p479l mutation might have affected the gut microbiota composition. To test this hypothesis, 16S rRNA sequencing were performed on fecal samples from male Cpt1a p479l mutated mice (n = 6) and male C57Bl/6J mice (n = 6). First, we assessed α-diversity using Shannon and Simpson index and found no differences between the groups (Fig. 6a). Next, we constructed heat maps at the phylum-, family- and genus level (Fig. 6b–d). At the phylum level, the 5 most abundant bacterial communities were firmicutes, bacteroidetes, verrucomicrobia, proteobacteria and actinobacteria (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, the abundance of verrucomicrobia and proteobacteria were remarkably low in the Cpt1a-mutated- compared to the WT mice, where actinobacteria were more prevalent. Following this, we constructed a heat map at the family level illustrating the 10 most abundant communities (Fig. 6c). Lachnospiraceae was remarkably more abundant in the Cpt1a-mutated mice, whereas akkermansiaceae- and rikenellaceae were less abundant. Subsequently, we assessed the 20 most prevalent bacterial communities at the genus level (Fig. 6d). Interestingly, the Cpt1a-mutated mice had higher abundance of faecalibaculum- and lower abundance of akkermansia-, alistepes communities compared to WT mice (Fig. 6d). Following the heap map analyses, we assessed significant differences at the genus level between Cpt1a-mutated- and WT mice and found 132 communities with significant differences between the two groups (Supplementary Table 1). This is the first time that CPT1A activity has been shown to affect the gut microbiota composition.

Figure 6.

Cpt1a-mutated mice have changes in their gut microbiota compared to WT mice. (a) Shannon and Simpson α-diversity measures in male Cpt1a-mutated (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 6). (b) The five most abundant bacterial communities at phyla level in male Cpt1a-mutated (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 6). (c) The ten most abundant bacterial communities at family level in male Cpt1a-mutated (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 6). (d) The 20 most abundant bacterial communities at genus level in male Cpt1a-mutated (n = 6) and WT mice (n = 6). Heat maps illustrate the relative abundance of the bacterial communities. Abbreviations: Cpt1a, carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a with a p479l mutation; WT, wild type.

Discussion

Neurodegenerative diseases such as MS, ALS, and PD, have a complex, and as of yet, unresolved origin and pathogenesis. As a result, only treatments that address specific symptoms exists at the moment. Here, we have presented that MS, ALS, and PD are characterized by local, and systemic changes in metabolism. Based on a CPT1A mutation found in the Inuit population, which seems to confer resistance to neurodegeneration by reducing CPT1A activity by 78%, we decided to test the effect of CPT1A de-activation in neurodegeneration in two ways: by pharmacologically blocking CPT1, and by creating a new Cpt1a p479l mice26. The findings from this study revealed that the Cpt1a-mutated mice are resistant to the development of not only EAE, but also PD and to some extent ALS. In addition, we tested the efficacy of a CPT1-antagonist, etomoxir, on the same animal models mimicking MS, ALS, and PD and revealed that it could reverse disease progression (Figs. 1, 4, 5).

CPT1, in its three isoforms, is regulated by the Peroxisome Proliferator Activated-Receptors (PPARs) in a tissue-dependent manner41–43. PPARs are regulators of multiple pathways including glucose- and lipid metabolism and the immune system44–46. As heterodimers with retinoid X receptor, they target genes that are involved in the regulation of mitochondrial- and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation, fatty acid transport, glucose transport and apolipoprotein synthesis and inflammatory enzymes. Furthermore, they regulate oxidants and chemoattractant ligands, differentiation and recruitment of T cells and cell apoptosis among others47,48. PPARs have been associated with CNS diseases in humans and in vivo models including MS, EAE, ALS, SOD1G93A, PD, and rotenone models49–53. Interestingly, several studies have shown that PPAR-α and PPAR-ϒ agonists ameliorate disease or disease progression in EAE-, rotenone-, and the SOD1G93A mouse models through mechanisms such as decreased demyelination, inhibition of Th1 differentiation and IFN-ϒ production54–56. Moreover, PPAR-α- and ϒ agonists decrease oxidative stress and increase mitochondrial biogenesis through Pgc1α in these models52,57. Etomoxir, our CPT1-antagonist, has been shown to upregulate PPAR-α58 and PPAR-ϒ59, which could explain the positive clinical effects seen in the EAE- (Fig. 1), SOD1G93A (Fig. 4) and rotenone (Fig. 5) models following treatment. Furthermore, Pgc1α was upregulated following etomoxir treatment (Fig. 1e) and Cpt1a mutation (Fig. 1k, 4j) indicating that downregulation of the metabolism of lipids by CPT1 has a positive effect through PGC1α.

Inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir has been shown to downregulate the production of reactive oxygen species60. We found a tendency towards a decreased gene expression of Nox-2 and Ho-1 in the hindbrain in the EAE models following downregulation of CPT1, and CPT1A (Fig. 1d–e,k). Nox-2 and Ho-1 have previously been found upregulated in MS, and EAE61,62. We also found, a tendency towards, upregulation of Nrf2, previously shown to protect against oxidative stress and correlated with disease activity in SOD1G93A model, in the SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice (Fig. 4j)63.

We have also previously shown that blocking CPT1 using etomoxir reduces demyelination, and increase apoptosis of MOG specific T-cells, decreases production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-17, and decrease production of IL-664,65. We found that Il-17α expression was significantly downregulated in the mid-, and hindbrain of EAE-Cpt1a mice (Fig. 1i) and SOD1G93A mice following etomoxir treatment (Fig. 4e). This indicates that downregulation of the metabolism of lipids through CPT1 results in a dampening of inflammation, which is supported by lower IL-6 and TNF-α levels in serum from the EAE experiments (Fig. 1f,m) and lower inflammatory gene expression in the spinal cord from the SOD1G93A experiments (Fig. 4e,j). Several studies have shown that metabolism plays a central role in the regulation of immune cells14,64,66. Some studies involved the use of etomoxir which was shown to downregulate the inflammatory properties of classical dendritic cells (DC) and increase insulin sensitivity by upregulating the metabolism of glucose through GLUT415,67,68. Correspondingly, we found that Cpt1a-mutated mice presented with changes in serum glucose, and lipoproteins in serum indicating changes in metabolism (Fig. 2a–d). These changes were most profound in the disease progression in the SOD1G93A/Cpt1a study (Fig. 4k).

Multiple factors can upregulate the metabolism of lipids through CPT1, such as a diet rich in high saturated fat and refined sugars. Multiple studies have found that HFD increases disease activity in EAE, ALS, and PD in vivo models69,70. Remarkably, here we found that Cpt1a-EAE mice receiving HFD had significantly lower disease activity compared to WT-EAE mice receiving HFD (Fig. 2g). We hypothesized that this severe disease progression could be due to several factors such as dysregulated mitochondrial function (Figs. 1k, 2h), decreased oxidative defense mechanisms (Figs. 1k, 2i), and inflammation (Fig. 2i) in WT-EAE mice receiving HFD. Another factor that could upregulate CPT1 lipid metabolism might be chronic hyperactivation of the HPA-axis leading to high levels of circulating corticosteroids, which has been reported for MS, ALS and PD71–73. The chronic hyperactivation of the HPA-axis results in glucocorticoid receptor resistance and runaway inflammation due to the failure of the negative glucocorticoid feedback mechanism74. Furthermore, dysregulation of the HPA-axis results in diminished secretion of insulin, and insulin resistance, resulting in a shift from glucose metabolism to lipid metabolism. In turns, this leads to more inflammation and catabolism of nearby lipids for energy gain75.

Our data also indicates that Cpt1a expression also regulates the function of the endothelial cells of the blood brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is crucial for healthy brain function, but remains a big challenge in drug delivery76. Many neurodegenerative diseases such as MS, ALS, and PD exhibit compromised BBB. The etiology of the leaky BBB is multifactorial and remains very partially understood. Here, we showed that the expression of Cpt1a in response to commonly prescribed drugs, VPA, and another HDACi inhibitor SB, affects BBB-associated cells (Fig. 3). Cpt1a expression increases significantly in pericytes and endothelial cells in response to treatment with VPA and SB, which is likely to lead to an increase in lipid metabolism at the blood–brain transition zone (Fig. 3a,b). Astrocytes, however, show different Cpt1a expression profiles depending on environmental and treatment cues, which might indicate that epigenetic mechanisms could be cell-specific (Fig. 3c). Recently, changes in the Cpt1a promoter epigenetic profile were reported in the livers of rats exposed to HFD, which supports the possibility that lipid metabolism can also have influence on the function and integrity of BBB32. Changes in histone H3 methylation significantly affected binding of the transcription factor PPARα to the Cpt1a promoter32. Moreover, acute hyperglycemia—due to an imbalanced glucose/lipid metabolism—has been shown to cause persistent epigenetic changes, including changes to Cpt1a77. These data, together with the data presented here, indicate that Cpt1a does respond to metabolic state through epigenetic processes32.

Our study has also shown that mice with a Cpt1a mutation exhibited a shift in their microbiota. The gut microbiota has been correlated with the development or protection from CNS diseases and with the modulation of the HPA-axis response from early life78,79. Furthermore, stimulates the intestinal gluconeogenesis, modulates glucose- and lipid metabolism, and plays a role in insulin resistance and inflammation80. Transplantation of feces from patients with neurodegenerative diseases exacerbates disease severity in animal models mimicking these diseases81,82. This indicates that the gut microbiome affects the CNS through involvement of systemic mechanisms. Our data confirms this link between the microbiota and the metabolism by showing that the de-activation of CPT1A modulates the gut microbiota (Fig. 6b–d). Interestingly, we found that several of the significantly changed bacterial communities between Cpt1a-mutated mice and WT mice have been reported to play a role in CNS diseases (Supplementary Table 1). Alistipes communities have been found significantly increased in humans with mood disorders83 and were correlated with the volatile fatty acids and cortisol levels84. Further, a higher abundance of Alistipes has been associated with type 2 diabetes85. Lachnospiraceae communities have been found decreased in CNS diseases and were generally more abundant in the Cpt1a mutant mice (Fig. 6c)86. Interestingly, Akkermansia communities have been found to increase the gut permeability and are correlated with PD disease severity and was less abundant in the Cpt1a-mutant mice (Fig. 6c–d)87. Faecalibaculum communities were significantly more abundant in the Cpt1a-mutant mice (Supplementary Table 1) and have been found decreased in multiple CNS diseases86. The bacterial genus Blautia has been found with anti-inflammatory properties and those were significantly higher in the Cpt1a-mutant mice (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, Blautia has been found to be decreased in PD patients5. Moreover, Rikenellaceae communities were significantly decreased in the Cpt1a-mutant mice (Fig. 6c). Interestingly, Rikenellaceae has been found elevated following HFD88. In addition, the gut microbiota is directly coupled with the diet of the animal or patient. A shift in microbiota has been seen in people under a western diet with high levels of fats and refined carbohydrates89. Through our study, we have confirmed that a high fat diet worsens disease severity and progression. The important question remains unanswered on whether the microbiota is changed due to the diet or due to the disease, and whether the disease is induced due to the change in microbiota or due to the diet itself. Our study indicates that it is the former: the CPT1A-mediated lipid metabolism modifies and possibly regulates the microbiota in the gut. Our data also confirms that there is a strong association between microbiota, diet, and disease development or progression. This suggests an important link between these environmental cues and the regulation of gut microbiota.

Based on the data presented here, we therefore suggest a new model to explain the development and progression of CNS diseases in which an imbalance between the metabolism of lipids and glucose is at the root of neurodegeneration (Fig. 7). A healthy state requires a homeostatic equilibrium between the HPA axis, immune system, microbiota, mitochondrial functioning, metal metabolism, redox state, and glucose-lipid metabolism. Our new model visualizes the possible interplay between these complex processes, and shows that, when imbalanced, they raise the likelihood of CNS disease development. Our study confirms that neurodegeneration is a multifactorial process: no single mechanism seems capable of explaining the complex nature of neurodegeneration in diseases such as MS, ALS, and PD. However, our experiments highlighted a key node in maintaining homeostasis: the activity of CPT1. This is the first time that a common, critical, and underlying pathological mechanism has been established for several neurodegenerative diseases based on experimental data. This model provides an open platform for future experiments and therapeutic targets.

Figure 7.

Novel proposed framework of CNS-related disease pathogeneses. We acknowledge Maria Rasmussen for drawing the figure.

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that CPT1 is a potential key candidate for the regulation of neurodegeneration, acting as the gate-keeper molecule in the homeostasis of lipid and glucose metabolism. Through pharmacological and animal model-based inhibition of CPT1, we have clearly shown that blocking the dysregulated metabolism of lipids offer profound beneficial effects in EAE, SOD1G93A/Cpt1a and rotenone diseases models through decreased inflammation, oxidative stress and increased mitochondrial biogenesis. Importantly, have demonstrated that MS, ALS, and PD, seems to share a common dysregulated metabolism of lipids. We have provided evidence that Cpt1a is epigenetically regulated, and that CPT1A lipid metabolism modulates the gut microbiome. Furthermore, we have proposed a new model to understand and target neurodegenerative diseases in future experiments.

Methods

Animals

The animal experiments were conducted according to NIH guidelines and were approved by the Danish National Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation (Mouse EAE: 2017-15-0201-01240, mouse ALS: 2017-15-0202-00088, mouse PD: 2017-15-0201-01328). All animals were housed in IVC cages and maintained under standardized conditions with a 12 h light–dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water.

Generation of Cpt1a P479L mice

To examine the role of CPT1A activity, a mouse line (B6J-Cpt1a < em1Nki >) expressing the Inuit mutant allele Cpt1a P479L (Cpt1a < em1Nki > , MGI number: 5810634) was generated and genotyped as previously described26.

Generation of SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice

To test the role of Cpt1a activity in the Sod1 g93a mouse model, mimicking ALS, we generated SOD1G93A mice with a Cpt1a point mutation. Briefly, B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J90 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Main, USA). Mice were acclimated for 3 weeks at 21 °C and kept in a high barrier facility (The Rodent Facility, Aalborg University Hospital). B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J males were crossed with homozygote B6J-Cpt1a < em1Nki > female mice. Litters were genotyped using DNA extracted from ear punch tissue using DNA kit (Zymo Research). Mice were genotyped by RT-qPCR using for the expression of the Sod1 g93a mutation using primer sequences: (SOD1G93A forward: GGG AAG CTG TTG TCC CAA G, SOD1G93A reverse: CAA GGG GAG GTA AAA GAG AGC, Internal positive control forward: CAC GTG GGC TCC AGC ATT, Internal positive control reverse: TCA CCA GTC ATT TCT GCC TTT G) (TAG Copenhagen) and the previously mentioned primer sequences for Cpt1a p479l26. RT-qPCR was performed as described below. SOD1G93A female mice with a heterozygote Cpt1a p479l mutation (SOD1G93A/Cpt1a) (n = 6) was used in subsequent experiment.

EAE experiments

Sex is known to affect susceptibility to specific diseases and because women are more susceptible to the development of MS, female mice were used in the EAE models1.To test the effect of blocking CPT1 by a CPT1-blocker, an EAE model was used26. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Janvier Laboratory (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) and were acclimated for 3 weeks at 21 °C in a high barrier before initiating experiment and kept in the Animal Facility at Aalborg University. The 8-week-old C57BL76J female mice (n = 12) were anesthetized with isoflurane and immunized subcutaneously in the base of the tail with 200 μg MOG35–55 (Pepmic) emulsified in complete Freund´s adjuvant (CFA) (Becton Dickinson) containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Becton Dickinson). All mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 500 ng pertussis toxin (Sigma-Aldrich) on the day of immunization and 2 days later. The mice were monitored daily and weighed and scored clinically according to a scale from 0 to 526. The mice were not permitted to lose more than 20% body weight and to go beyond score 4. Mice (n = 7) were treated with etomoxir25 (5 mg/kg) (Meta-IQ ApS) or placebo (olive oil) treatment (n = 5) from day 10. To test whether CPT1a activity modulated EAE disease severity, we conduct an animal experiments using female Cpt1a-mutated mice. Eight-week-old C57BL76J female mice (n = 5) and Cpt1a p479l female mice (n = 6) were induced with EAE as described above. The mice were assessed daily for animal welfare, weighed and scored clinically according to a scale from 0 to 526. The mice were not permitted to lose more than 20% body weight and to go above a clinical score of 4. Further, to test the effect of high fat diet, 8-week-old C57BL76J female mice (n = 5) and Cpt1a p479l female mice (n = 6) were induced with EAE as described above and from day 10, the mice received high-fat diet (HFD) (kcal% respectively: protein 20, carbohydrate 20, fat 60, Brogaarden, Denmark; based on D12492 research diets, New Brunswick, USA) throughout the experiments.

SOD1 G93A experiments

Humans with SOD1 mutations have an approximately female/male ratio of 1 and because of this females were chosen for the SOD1G93A model17.To test whether blocking CPT1 could modulate disease progression in ALS, we used the SOD1 G93A mouse model. B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Main, USA)90. Mice were kept in a high barrier facility (The Animal Facility, Aalborg University). B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J male mice were breed with C57Bl/6J female mice. Genotypes were evaluated using DNA extracted from ear tissue punches. RT-qPCR was performed using previously described primer sequences according to protocol91. Transgenic SOD1G93A female mice were used for experiments (n = 14). SOD1G93A mice were randomized into treatment with either etomoxir (5 mg/kg dissolved in olive oil) or placebo (olive oil) daily by oral gavage from day 70 (baseline) (Fig. 4a). SOD1G93A mice were evaluated with a neurological score system weekly as previously described92 and weighted two times a week. SOD1G93A mice and ALS patients’ losses muscle strength as the disease progresses and therefore muscle strength were assessed weekly using a grip strength meter (Bioseb, France). Grip strength were measured in grams and normalized to weight according to protocol93. Furthermore, neurological function and muscle strength were assessed using the hang-wire test as previously described92,93. Briefly, mice were put on a wire lid and gently turn upside down. The time until the mice fell down was measured (latency to fall), cutoff time was set to 180 s. Each mice performed three trails and the highest value was used for statistics as previously described92,94. Mice were euthanized when they reached a neurological score of 4 or above or if they had a weight loss of 20% or more according to ethical guidelines. The SOD1G93A/Cpt1a mice (n = 6) were evaluated with the same procedures from day 70 until day 127 (Fig. 4f).

Rotenone experiments

Men have a higher incidence of PD compared to women and, accordingly, we conducted our chronic rotenone model using male mice3. To assess whether blockage of CPT1 or CPT1A activity had a role in PD, we used a chronic rotenone mouse model as previously described95. Rotenone has been shown to upregulate lipid metabolism through CPT196. Briefly, C57BL/6J male mice were obtained from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France). Mice were acclimated for 3 weeks at 21 °C in a high barrier animal facility. Cpt1a p479l mice were generated and breed as previously described26. Mice were 9 weeks old when the experiment initiated. Mice were weighted once a week throughout the experiments.

Rotenone is a pesticide and has been used in several animal models of PD53,95,97,98. We used a chronic oral gavage, dosing regimen similar to the process reported by others95,97. Mice were randomized into a group receiving 30 mg/kg rotenone (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 83-79-4) suspended in 0.5% Carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt (CMC) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 9004-32-4) or a group receiving CMC as vehicle daily.. Animals were evaluated by grip strength test as previously described93. Rotarod test (Rotamex-5 RotaRod, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, Ohio, USA) with an acceleration from 4 to 40 RPM over 180 s. Mice were acclimatized to the rotarod over three consecutive days. Each mouse was tested 3 times to obtain a mean latency to fall (s). Mice were evaluated for sensorimotor symptoms by the cylinder test as previously described99.

For the etomoxir treatment experiment the following groups were used: wildtype mice receiving rotenone (n = 20), and wildtype mice receiving vehicle (n = 5) for 32 days. Animals, which did not show sign of disease defined by the presence of minimum two of the following factors: lower grip strength, lower latency to fall on the rotarod and/or lower number of rears in the cylinder test compared to the healthy control group, was excluded from treatment groups (n = 2) at day 32. At day 33 12 weeks old C57BL/6J mice receiving rotenone were randomized into two groups (Fig. 4a). One receiving etomoxir at 5 mg/kg dissolved in olive oil (n = 9) and another receiving only olive oil as placebo (n = 9). At this point, the daily administration of rotenone was changed to every second day. This intervention was given every second day in between the rotenone and CMC administration, day 33, 35 etc. At day 62, the experiment ended. Thus, making it a total of 43 rotenone administrations spanning along 61 days. The etomoxir intervention group had 18 administrations of etomoxir over a span of 28 days, receiving etomoxir without rotenone intervention from day 50 until 56 and again form day 58 to 60. Animals were evaluated for rotenone induced behavioral deficits at day 32 and day 60, except for the cylinder test which was conducted at day 32 and day 56.

The following groups were used in the Cpt1a-mutant experiment; Cpt1a-mutant mice receiving rotenone (n = 7), wildtype mice receiving rotenone (n = 10), and wildtype mice receiving vehicle (n = 5) for 32 days (Fig. 4e). Animals were evaluated for rotenone induced behavioral deficits using rotarod, grip strength, and cylinder test at day 32.

Chronic high fat diet model and Cpt1a mutant versus wildtype experiment

10 week old female C57BL/6J mice (n = 8) from our animal facility were randomized into receiving either normal diet (kcal% respectively: protein 29, carbohydrate 65.5, fat 5.5, Brogaarden, Denmark) or HFD (kcal% respectively: protein 20, carbohydrate 20, fat 60, Brogaarden, Denmark; based on D12492 research diets, New Brunswick, USA) for 10 weeks as previously described100. After 10 weeks the mice were terminated and spinal cord tissue were quickly harvested and stored at − 80 °C until further analyses. For assessment for differences in serum glucose, LDL, and HDL we used 10 weeks old C57Bl/6J (n = 15), and Cpt1a mutant male mice (n = 12). Blood was sampled by retroorbital puncture, and serum was obtained as described below.

Serum glucose, LDL and HDL analyses

Animals were placed in cages without access to food for 1 h before termination. Blood were obtained from animals and placed at room temperature for minimum 40 min. Afterwards samples were centrifuged at 3500 g for 15 min and the supernatant was transferred and stored at − 80 °C until further analyses. Serum analyses of glucose- (Crystal Chem, Cat. 81692), LDL- (Crystal Chem, Cat. 79980) and HDL- (Crystal Chem, Cat. 79990) levels were performed using commercial mouse assay kits according to the manufactures protocol. Samples- and standards were run in duplicates and were analyzed using a multiplate reader (PerkinElmer). Concentrations were estimated according to standard curve methods as described in the manufacture’s protocols.

Gene expression analyses in EAE- and SOD1G93A models

RNA was extracted from the hindbrain, midbrain and frontal lobe for the EAE studies and lumbar spinal cord for the SOD1G93A experiments as previously described26. cDNA was synthesized as previously described according to the manufactures protocol26. Reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed as previously described using β-actin as housekeeping gene26. Samples were run in triplicates for the EAE studies and duplicates for the SOD1G93A, Cpt1a versus WT and chronic high fat diet model. Following RT-qPCR fold gene expression was determined using 2−∆∆CT method as previously described26. Nox-2, Ho-1, Nrf2- and Pgc1α primer sequences were as previously described26. The following primers were purchased from QIAGEN; Casp1 (PPM02921E), Il-17α (PPM03023A-200), Ifn-ϒ (PPM03121A-200).

ELISA

ELISA was performed using commercial kits for IL-6 (Invitrogen, Cat. 88-7064) and TNF-α (Invitrogen, Cat. 88-7324). Procedures were done according to manufactures protocols. Standards- and samples were run in duplicates. OD values were read at 450 nm using a multiplatereader (PerkinElmer). Calculation of concentrations were done according to manufactures protocol using standard curve methods.

Microbiota analyses

To assess whether CPT1a activity had any impact on gut microbiome community, we investigated changes in the gut microbiota using male Cpt1a-muated mice and male wildtype mice. Briefly, fecal samples were collected from 12 week old male Cpt1a mice and male wildtype C57Bl/6J mice from Aalborg University animal facility and quickly stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Animals were housed together under identical conditions (bedding, pellets, water and ventilation). 16S rRNA analyses were performed by DNASense APS (Aalborg, Denmark).

DNA extraction

DNA extraction was performed using the standard protocol for FastDNA Spin kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals) with the following exceptions. 500 L of sample, 480 L Sodium Phosphate Buffer and 120 L MT Buffer were added to a Lysing Matrix E tube. Bead beating was performed at 6 m/s for 4 × 40 s. Gel electrophoresis using Tapestation 2200 and Genomic DNA screentapes (Agilent) was used to validate product size and purity of a subset of DNA extracts. DNA concentration was measured using Qubit dsDNA HS/BR Assay kit (Thermo Scientific).

Bacterial and Archaeal community analysis targeting 16S V4 rRNA

Bacteria and Archaea, 16S rRNA region V4 sequencing libraries were adapted by a custom protocol established on an Illumina protocol (Illumina, 2015) . Extracted DNA (maximum 10 ng) was used as template for Polymerase Chain Reaction amplification of the Bacteria and Archaea, 16S rRNA gene region V4 amplicons. Each Polymerase Chain Reaction reaction (25µL) contained dNTPs (100 M of each), MgSO4 (1.5 mM), Platinum Taq DNA polymerase HF (0.5 U/reaction), Platinum High Fidelity buffer (1X) (Thermo Scientific) and tailed primer mix (400 nM of each forward and reverse primer). Polymerase Chain Reaction was done with the following settings: denaturation at 95 C for 2 min, 30 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s, 72° C for 50 s) and a terminal elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. Polymerase Chain Reaction reactions were performed in duplicate for each sample and the duplicates were pooled following Polymerase Chain Reaction. The forward and reverse tailed primers were designed according to101 and contain primers targeting the Bacteria and Archaea, 16S rRNA gene region V4: [806RB] GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT and [515FB GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA]102. The amplicon libraries were purified based to the manufactures protocol using Agencourt Ampure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) with a sample bead to ratio of 5:4. DNA was eluted in 25 µL of nuclease free water (QIAGEN). DNA concentration was confirmed using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Gel electrophoresis using Tapestation 2200 and D1000/High sensitivity D1000 screentapes (Agilent) was used to validate product size and purity of a subset of sequencing libraries. Sequencing libraries were established from the cleaned amplicon libraries using a second Polymerase Chain Reaction. Each reaction (25 µL) contained PCRBIO HiFi buffer (1x), PCRBIO HiFi Polymerase (1 U/reaction) (PCRBiosystems), adaptor mix (400 nM of each forward and reverse) and up to 10 ng of amplicon library template. Polymerase Chain Reaction was done as follows: denaturation at 95 C for 2 min, 8 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 60 s) and a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. The final sequencing libraries were purified according to the manufactures protocol using Agencourt Ampure XP Beads (Beckman Coulter) with a sample to bead ratio of 5:4. DNA was eluted in 25 µL of nuclease free water (QIAGEN). DNA concentration was quantified using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Gel electrophoresis using Tapestation 2200 and D1000/High sensitivity D1000 screentapes (Agilent,) was used to validate product size and purity of a subset of sequencing libraries.

The purified libraries were pooled in equiM concentrations and diluted to 2 nM. The samples were sequenced paired-end (2 × 300 bp) on a MiSeq (Illumina, USA). Sequencing was performed using Reagent kit version 3 (Illumina, USA) following the Illumina guidelines for preparing and loading samples on the MiSeq. > 10% PhiX control library was spiked in to overcome low complexity issues often observed with amplicon samples103.

Bioinformatic processing

Forward and reverse reads were trimmed for quality using Trimmomatic v. 0.32104 with the settings SLIDINGWINDOW:5:3 and MINLEN: 225 . The trimmed forward and reverse reads were merged using FLASH v. 1.2.7105 with the settings -m 10 -M 250. The trimmed reads were dereplicated and formatted for use in the UPARSE workflow106. The dereplicated reads were clustered, using the usearch v. 7.0.1090 -cluster_otus command with default settings. OUT abundances were estimated using the usearch v. 7.0.1090 -usearch_global command with -id 0.97 -maxaccepts 0 -maxrejects 0. Taxonomy was assigned using the RDP classifier107 as implemented in the parallel_assign_taxonomy_rdp.py script in QIIME108, using—confidence 0.8 and the SILVA database, release 132109. The results were analysed in R v. 3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2017) through the Rstudio IDE using the ampvis package v.2.4.2103.

Primary cell cultures and treatment

Brain capillary endothelial cells (BCEC) and pericytes were isolated from 2 to 3 weeks old Sprague–Dawley rats. Primary BCECs were cultured in DMEM/Nutrient F-12 Ham (Invitrogen, Cat. 31331-028) with 10% plasma derived bovine serum (First Link, Wolverhampton, United Kingdom, UK), insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (1:100) (Sigma Aldrich I1884), gentamicin sulphate (10 μg/ml), and basic fibroblast growth factor (1 ng/ml) (Roche). To ensure a pure BCEC culture, puromycin (1 μl/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the medium.

Primary astrocytes were isolated from neonatal Sprague–Dawley rats and cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Cat. 10106-169), fetal calf serum (10%) (Gibco, Cat. 10106-169), and gentamicin sulphate (10 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 17-518Z).

After cell culturing the cells were either used as control cells (n = 3) and/or were treated with and sodium butyrate (2 mM) (SB) (Sigma-Aldrich) or sodium valproate (4 mM) (VPA) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6- and 24 h (all treatments n = 3). VPA is specific for histone deacetylase (HDAC) class I and IIa, whereas SB inhibits HDAC class IV alongside class I and IIa110.

RNA purification cDNA synthesis

RNA from all samples was purified using AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini kit (QIAGENgen, Cat. 80204) followed by genomic DNA contamination removal using a DNase kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat. EN0525). cDNA was synthesized using Maxima H Minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, Cat. K1651).

RT-qPCR

Reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using an AriaMX qPCR machine (Agilent). The following primers were used: Cpt1a (QIAGEN), Cpt1c (QIAGEN), Hprt1 (5′TGCAGACTTTGCTTTCCTTGGTCA3′, 5′-TGGCCTGTATCCAACACTTCGAG3′) All samples were run in triplicates. The relative expression of the Cpt1a was calculated according to previously published methods111.

Statistics

Data was evaluated for normality using Shapiro–wilk test and Q/Q-plots. If normality was present unpaired t tests, ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test, ordinary two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons post hoc test, or repeated measures (RM) two-way ANOVA followed by either Tukey’s, Sidak’s or Bonferroni multiple comparisons post hoc test were used to assess statistical significance. If the criteria of normality was not met, a non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was performed. The fold of gene expression was calculated according to previously published methods111. All statistics were performed using Graph Pad Prism software. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM, unless otherwise stated. To evaluate possible outliers, a Grubbs test was performed, and outliers were removed. P-values of 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Aage and Johanne Louis-Hansens Foundation (17-2B-1297) and Gangstedfoundation (A33337) for providing funding for M.S.T and Lundbeck Foundation for funding for A.S.M. (R191-2015-1118). We acknowledge Svend Andersen Foundation for providing funding for D.C.A. We acknowledge DNASense APS (Aalborg, Denmark) for assisting with 16s rRNA sequencing. We thank Meta-IQ ApS (Aarhus, Denmark) for providing etomoxir.

Author contributions

M.S.T., A.S.M., D.C.A, K.M. and M.-L.N.S. performed the animal experiments. J.L. and K.J. performed the epigenetic experiments. M.S.T. planned the 16S rRNA experiments, performed ELISA-, serum-, and RT-qPCR experiments for the Cpt1a-mutant, SOD1G93A, and WT-HFD model. A.S.M. performed RT-qPCR experiments for the EAE models. M.S.T., A.S.M and J.L. performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. M.S.T. revised the manuscript and prepared final figures. L.J.K., C.E.J.P. and I.J.H. developed the Cpt1a-mutated mice. M.K.E.O wrote, A.C., P.G, and J.D.V.N. wrote, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Data are available upon relevant request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-72638-8.

References

- 1.Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:545–558. doi: 10.1038/nri3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancuso R, Navarro X. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: current perspectives from basic research to the clinic. Prog. Neurobiol. 2015;133:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Es MA, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390:2084–2098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu S, et al. The progress of gut microbiome research related to brain disorders. J. Neuroinflam. 2020;17:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1655-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo X, et al. The serum lipid profile of Parkinson’s disease patients: a study from China. Int. J. Neurosci. 2015;125:838–844. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2014.979288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pradat PF, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010;11:166–171. doi: 10.3109/17482960902822960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergani A, et al. Increased peripheral lipid clearance in an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:1571–1580. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700017-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reale M, Sanchez-Ramon S. Lipids at the cross-road of autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017;24:176–192. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666161123093606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jurewicz A, Domowicz M, Galazka G, Raine CS, Selmaj K. Multiple sclerosis: presence of serum antibodies to lipids and predominance of cholesterol recognition. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017;95:1984–1992. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corthals AP. Multiple sclerosis is not a disease of the immune system. Q. Rev. Biol. 2011;86:287–321. doi: 10.1086/662453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haider L, et al. Oxidative damage in multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain. 2011;134:1914–1924. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang P, Xie K, Wang C, Bi J. Oxidative stress induced by lipid peroxidation is related with inflammation of demyelination and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Eur. Neurol. 2014;72:249–254. doi: 10.1159/000363515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Windt GJW, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8 + T cell memory development. Immunity. 2012;36:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu CC, Atencio AE, Gallucci S. Inhibition of fatty acid metabolism by etomoxir or TOFA suppresses murine dendritic cell activation without affecting viability. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2019;41:361–369. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2019.1616754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bose A, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016;139:216–231. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown RH, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:162–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1603471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng P, Zhou X. Causal effects of blood lipids on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a Mendelian randomization study. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019;28:688–697. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodge JC, et al. Metabolic signatures of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveal insights into disease pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308421110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palamiuc L, et al. A metabolic switch toward lipid use in glycolytic muscle is an early pathologic event in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015;7:526–546. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houten SM, Wanders RJA. A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9061-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell RW, On NH, Del Bigio MR, Miller DW, Hatch GM. Fatty acid transport protein expression in human brain and potential role in fatty acid transport across human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J. Neurochem. 2011;117:735–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Leij FR, Huijkman NCA, Boomsma C, Kuipers JRG, Bartelds B. Genomics of the human carnitine acyltransferase genes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000;71:139–153. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieury A, et al. Tissue remodeling in periplaque regions of multiple sclerosis spinal cord lesions. Glia. 2014;62:1645–1658. doi: 10.1002/glia.22705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mørkholt AS, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 inhibits and reverses experimental autoimmune encephalitis in rodents. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0234493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mørkholt AS, et al. CPT1A plays a key role in the development and treatment of multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat. Protocol. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajakumar C, et al. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase IA polymorphism P479L is common in Greenland Inuit and is associated with elevated plasma apolipoprotein A-I. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:1223–1228. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900001-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Collins SA, et al. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A) P479L prevalence in live newborns in Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;101:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun HY, Lee T, Jeong Y. High-fat diet increases fat oxidation and promotes skeletal muscle fatty acid transporter expression in exercise-trained mice. J. Med. Food. 2020;23:281–288. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2019.4651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saeedi J, Rieckmann P, Yee I, Tremlett H. Characteristics of multiple sclerosis in aboriginals living in British Columbi, Canada. Mult. Scler. J. 2012;18:1239–1243. doi: 10.1177/1352458512436595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck CA, Metz LM, Svenson LW, Patten SB. Regional variation of multiple sclerosis prevalence in Canada. Mult. Scler. 2005;11:516–519. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1192oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moody L, Xu GB, Chen H, Pan YX. Epigenetic regulation of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (Cpt1a) by high fat diet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2019;1862:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tobi EW, et al. DNA methylation signatures link prenatal famine exposure to growth and metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasco H, et al. Lipidomics reveals cerebrospinal-fluid signatures of ALS. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17389-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szelechowski M, et al. Metabolic reprogramming in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22318-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tracey TJ, Steyn FJ, Wolvetang EJ, Ngo ST. Neuronal lipid metabolism: multiple pathways driving functional outcomes in health and disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:1–25. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunn L, et al. Dysregulation of glucose metabolism is an early event in sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burté F, et al. Metabolic profiling of Parkinson’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Mov. Disord. 2017;32:927–932. doi: 10.1002/mds.26992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okuzumi A, et al. Metabolomics-based identification of metabolic alterations in PARK2. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019;6:525–536. doi: 10.1002/acn3.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia W, Li H, Zhao L, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiota: a potential new territory for drug targeting. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:123–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lodhi IJ, Semenkovich CF. Peroxisomes: a nexus for lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Cell Metab. 2014;19:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krishnan J, et al. Activation of a HIF1α-PPARγ axis underlies the integration of glycolytic and lipid anabolic pathways in pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. Cell Metab. 2009;9:512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grimaldi B, et al. PER2 controls lipid metabolism by direct regulation of PPARγ. Cell Metab. 2010;12:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bocher V, Pineda-Torra I, Fruchart JC, Staels B. PPARs: transcription factors controlling lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002;967:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khovidhunkit W, et al. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J. Lipid Res. 2004;45:1169–1196. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R300019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang JK, et al. Retinoid X receptor gamma signaling accelerates CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barish GD, et al. PPARδ regulates multiple proinflammatory pathways to suppress atherosclerosis. PNAS. 2008;105:4271–4276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711875105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall MG, Quignodon L, Desvergne B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta in the brain: facts and hypothesis. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:780452. doi: 10.1155/2008/780452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu J, Racke MK, Drew PD. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha agonist fenofibrate regulates IL-12 family cytokine expression in the CNS: relevance to multiple sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2007;103:1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drew PD, Xu J, Racke MK. PPAR-gamma: therapeutic potential for multiple sclerosis. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:627463. doi: 10.1155/2008/627463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiaei M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Huntington’s disease. PPAR Res. 2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/418765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carta AR, Pisanu A, Carboni E. Do PPAR-gamma agonists have a future in parkinson’s disease therapy? Parkinsons Dis. 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/689181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corona JC, de Souza SC, Duchen MR. PPARγ activation rescues mitochondrial function from inhibition of complex I and loss of PINK1. Exp. Neurol. 2014;253:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niino M, et al. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BLr6 mice by an agonist of peroxisome. J. Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(01)00285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Natarajan C, Bright JJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist inhibit experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by blocking IL-12 production, IL-12 signaling and Th1 differentiation. Genes Immun. 2002;3:59–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanakasabai S, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ agonists inhibit T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th17 responses in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Immunology. 2010;130:572–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benedusi V, Martorana F, Brambilla L, Maggi A, Rossi D. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) controls natural protective mechanisms against lipid peroxidation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:35899–35911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rupp H, Rupp TP, Maisch B. Fatty acid oxidation inhibition with PPARα activation (FOXIB/PPARα) for normalizing gene expression in heart failure? Cardiovasc. Res. 2005;66:423–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng S, et al. Fatty acid oxidation inhibitor etomoxir suppresses tumor progression and induces cell cycle arrest via PPARγ-mediated pathway in bladder cancer. Clin. Sci. 2019;133:1745–1758. doi: 10.1042/CS20190587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown ZJ, et al. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase gene upregulation by linoleic acid induces CD4+ T cell apoptosis promoting HCC development. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0687-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ravelli KG, et al. Nox2-dependent neuroinflammation in an EAE model of multiple sclerosis. Transl. Neurosci. 2019;10:1–9. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2019-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakrabarty A, Emerson MR, LeVine SM. Heme oxygenase-I in SJL mice with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Mult. Scler. 2003;9:372–381. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms928oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo Y, et al. The modest impact of transcription factor Nrf2 on the course of disease in an ALS animal model. Lab. Investig. 2013;93:825–833. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shriver LP, Manchester M. Inhibition of fatty acid metabolism ameliorates disease activity in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2011;1:79. doi: 10.1038/srep00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mørkholt AS, Wiborg O, Nieland JGK, Nielsen S, Nieland JD. Blocking of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 potently reduces stress-induced depression in rat highlighting a pivotal role of lipid metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Der Windt GJW, et al. CD8 memory T cells have a bioenergetic advantage that underlies their rapid recall ability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:14336–14341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221740110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Giles DA, Duncker PC, Wilkinson NM, Washnock-Schmid JM, Segal BM. CNS-resident classical DCs play a critical role in CNS autoimmune disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2018;128:5322–5334. doi: 10.1172/JCI123708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Timmers S, et al. Augmenting muscle diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol content by blocking fatty acid oxidation does not impede insulin sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:11711–11716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206868109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]