Highlights

-

•

Langerhans` Cell Histiocytosis is a rare disease involving proliferation of Langerhans-type cells, which shares immunophenotypic and ultrastructural similarities.

-

•

LCH occurs dominantly in pediatric ages and involve cranium, pelvis, vertebrae, ribs, tubular bones and so forth.

-

•

It is diagnosed by the means of histologic, immunochemical analysis.

-

•

We encountered a very rare case of solitary LCH in an adult’s clavicle.

-

•

We concluded LCH must be suspected as a diagnosis and ruled out when encountering primary tumorous lesion.

Abbreviations: LCH, Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis

Keywords: Diagnosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Clavicle, Tumorous lesion, Biopsy

Abstract

Introduction

Langerhans` Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease involving proliferation of Langerhans-type cells, which shares immunophenotypic and ultrastructural similarities. In this article, we report a case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in solitary involvement of clavicle of adult male.

Presentation of case

A 21-year-old male visited outpatient department on account of solitary palpable tumorous lesion in right clavicle. The lesion was found 2 weeks before the visit, and it triggered pain but no tenderness. Findings on X-ray, and CT were suggestive of homogeneous osteolytic lesion of the clavicle, and hot uptake was found in right clavicle on bone scan which is commensurate with site of the lesion. Based on findings on MRI, Ewing's sarcoma, osteomyelitis and malignant hematologic malignancies were initially suspected for differential diagnosis. For the purpose of excision and histologic analysis, excisional biopsy was performed. Biopsy concluded with diagnosis of LCH.

Discussion

LCH is widely renowned for its frequent occurrence in pediatric ages, and it occurs usually between ages of one and four. It occasionally occurs in adults. LCH in skeletal system usually involves cranium, vertebrae, rib and so forth. It is very rare for LCH to occur exclusively in clavicle when it involves skeletal system.

For diagnosis of LCH, sole imaging studies are inadequate, and histologic, immunochemical analyses are confirmative modalities. Treatment of LCH is not currently standardized.

Conclusions

Most of the solitary tumorous lesions in clavicle in adults call for various differential diagnoses. LCH should be considered in the diagnosis of a adult patient with a clavicle mass.

1. Introduction

Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease involving proliferation of Langerhans-type cells, which shares immunophenotypic and ultrastructural similarities. It can be found in every organ of the body, and is considered to be predominantly occur in childhood [1,2]. In the case of single-system LCH, the most commonly involved organ is the skeleton [3]. The mainly involved parts are cranium, pelvis, vertebrae, ribs, tubular bones and so forth [4]. We herein aim to report a rare case of LCH in the adult clavicle with a review of the literatures. This article has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

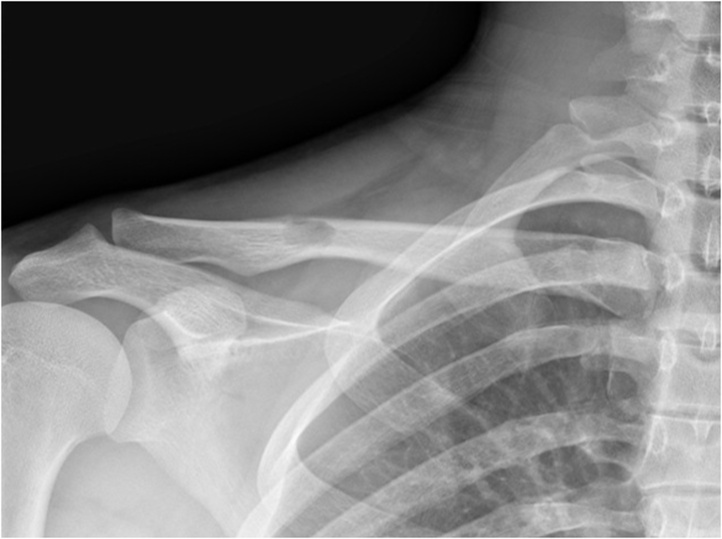

A 21-year-old man presented with a palpable mass on his right clavicle without any previous medical history. The patient had a healthy figure with a height of 170.2 cm and a weight of 71 kg (BMI 24.5Kg/m2), and was non-smoker and social drinker. The mass on the right clavicle was palpable 2 weeks before admission, bulging upwards on the middle portion of the right clavicle. Upon physical examination, the mass was measured to be about 3 cm in size, and painful but non-tender. Imaging studies were planned for further evaluation. On the simple radiograph (Fig. 1) and the computed tomography(Fig. 2), an osteolytic lesions with the size of 1.6 cm in diameter was observed at the midportion of right clavicle, accompanied by periosteal reaction.

Fig. 1.

Radiograph of the right clavicle at the initial X-ray: Anteroposterior view : an approximately 1.6 cm sized osteolytic lesion is seen.

Fig. 2.

CT reconstruction images show an approximately 1.6 cm sized osteolytic (a), and a disruption of the upper cortex in the diaphysis of the Rt. Clavicle(b).

In the whole-body bone scan, partial increase in uptake rate on the right clavicle was found, while no increase in other sites (Fig. 3). On the T2-weighted magnetic resonance image, a 1.6 cm-sized, homogeneously enhanced mass was found at the periphery of the midportion of the right clavicle (Fig. 4). The findings of cortical bone destruction were not prominent, while the findings of MRI suggested the possibilities of Ewing’s sarcoma, malignant hematologic malignancy (especially multiple myeloma) and osteomyelitis.

Fig. 3.

On Bone scan, focal hot uptake is noted in the right clavicle.

Fig. 4.

Shoulder MRI. An low intensity lesion is noted at the mid shaft of right clavicle of T1-WI (a), high intensity lesion in T2-WI (b), and high intensity lesion in enhanced T1 -WI (c). Multiple Lymph node enlargement is also observed in the right neck and axillary areas.

An incisional biopsy was performed on the mass for histologic confirmation. In intraoperative frozen section examination, the mass was suspected to be an inflammatory lesion, and not a tumor. The cells were positive for CD1a, CD68, and S-100 on immunohistochemical staining in formalin-fixed tissue. With these overall findings, the patient was confirmed with a diagnosis of LCH (Fig. 5). The patient underwent curettage of the lesion and autologous iliac bone graft.

Fig. 5.

(A) Histologic examination of resected specimen reveals fibro-osseous tissue replaced by dense inflammatory cell infiltrations (H&E, x100).

(B) At high power view, some characteristic Langerhans cells with distinct acidophilic cytoplasm were noted in the background of a heterogeneous admixture of eosinophils, plasma cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes (H&E, x400).

(C) Immunohistochemical study shows strong membranous positivity of CD1a and (D) cytoplasmic positivity of S-100 (x200).

Discomforts on the right clavicle improved after the surgery, and the patient was treated with adjuvant radiation therapy. At 10 months postoperative follow-up, the radiologic findings suggested that surgical site was sufficiently healed with no evidence of recurrence even in other sites of the body (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Post operative radiograph of the right clavicle taken 10 months after surgery: Anteroposterior view: osteolytic lesion disappeared and consolidation of bone graft with significant homogeneity.

3. Discussion

LCH is characterized by abnormal proliferation of Langerhans cells associated with eosinophils, formerly called Histiocytosis-X. It may involve almost all organs in the body, including skin, liver, spleen, lung and lymph nodes and can be classified as Letterer-Siwe, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, and eosinophilic granuloma (unifocal LCH with a solitary bone lesion) depending on the clinical symptoms [4]. In the case of single-system LCH, the most commonly involved organ is the skeletal system [3]. The involvement of the skeletal system by LCH may occur in single- or multiple-form, with single lesions to be more commonly found [6]. The most common site of involvement is the flat bone, especially the skull, which is followed by the pelvic bone, the vertebra, the mandible, and the rib among the flat bones [4]. The LCH cases with sole involvements of clavicles are rarely reported worldwide. More than one third of LCH involving the skeletal system were found to involve the long bone, and the commonly involved long bone is the femur, humerus and tibia [7]. LCH is commonly found in all ages, but is predominantly found in childhood. The most prevalent age of the disease is between 1–4 years old [1,2]. Incidence of the disease in children is reported to be 2–10 per million, while that of the adults to be lower, 1–2 per million [8]. With investigation on the differences in the involved skeletal sites between adults and children, it is found that in adults, the skull, ribs, jaw, femur and pelvic bone in order were most commonly affected sites, while skull, femur, jaw, pelvic bone and spine in order in children [6].

For differential diagnosis of solitary tumorous lesion in clavicle, malignant tumors such as Ewing’s sarcoma, plasmacytoma or benign tumors such as need to be considered and no single disease was predominant diagnosis [9,10]. However, Ke Ren et al. stated that primary clavicular tumor or tumor like lesion must be suspected for eosinophilic granuloma as a major pathological type which accounts for 18.5 % of all cases in an analysis of 206 east Asian population with solitary tumorous lesion in clavicle [11]. It is essential for surgeons to take LCH into consideration for diagnosis of primary clavicular tumor lesion.

The main clinical manifestations of patients diagnosed with LCH involving bones are regional pain, and edema with pain in adjacent soft tissue. For example, with involvement of jaw, soft tissue swelling, loosened teeth and avulsed teeth can be observed, while with involvement of spine vertebral, the collapse of vertebral body caused by osteolysis may result in vertebral plana [1,4]. In the case of our patient, regional pain and edema on adjacent soft tissue were observed.

The most basic examination to evaluate skeletal mass is plain radiography. The imaging findings can vary depending on the affected site and stage of the lesion. Bone involvement can be found as a round or elliptical osteolytic lesion. The margin of lesion can be either clear or unclear. Since a lesion, especially when it is of an acute onset, can be more fast-growing and observed to be osteolytic lesion with indistinct margin, it is necessary to differentiate the lesion from malignant lesions such as Ewing's sarcoma or infectious lesions such as osteomyelitis [4,6].

Computed tomography may also help determine the presence of periosteal destruction and surrounding soft tissue involvement, but may not differentiate it from osteomyelitis and Ewing's sarcoma. On the other hand, magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in identifying bone marrow involvement and lesion invasion into the surrounding soft tissue, and differentiating it from inflammatory/infectious diseases [4]. In this case, homogeneous osteolytic lesion and a punctate shape of lesion in the cavernous bone in the clavicle were observed on simple radiograph. On magnetic resonance imaging, a low signal was observed on the T1-weighted images, a high signal on the T2-weighted images, and a high signal on the enhancement images. No signs of periosteal new bone formation were observed. Since there were limitations with clinical and imaging findings to making a definite diagnosis, the diagnosis of the lesion was confirmed by incisional biopsy.

The diagnosis of LCH can be confirmed by histological examination and immunohistochemical staining. Proliferation of Langerhans cells with characteristic morphological features and immunophenotypes are histologically observed. Langerhans cells are 12–15 μm in diameter and have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The nucleus has an irregular pattern of nuclear membrane with a large number of wrinkles smooth chromatin and indistinct nucleolus. Eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils are present in the surrounding tissues with varied ratio [3]. The S-100 and CD1 positivitivity of Langerhans cells in immunohistochemical staining is a necessary finding for the diagnosis [4]. Although the findings of Birbeck granule in cytoplasm under electron microscope observation can be helpful, due to many limitations in diagnosis using electron microscopy, Langerin (CD207) has been recently used as a new immunostaining marker [3,12]. In the case of our patient, a large number of characteristic Langerhans cells were observed at high magnification and positivity for CD1a and S-100 immunostaining helped confirm the diagnosis of LCH.

The treatment of LCH is not standardized because of its broad clinical spectrum, but it can be determined depending on the extent of disease involvement [4]. In a case of single-system LCH, especially a single lesion in the skeletal system, the treatment strategy is determined according to the location of the lesion and the clinical condition [2]. In asymptomatic cases, it may resolve spontaneously, or with percutaneous biopsy. Single-site bone lesion can be treated with adequate bone curettage, and CT-guided methylprednisolone injection can be performed in some cases. Systemic treatment with vinblastine or prednisolone may be used for multiple bone involvement [4].

In cases that Ukada et al. reported in 2015, symptoms were relieved by bone curettage combined with biopsy [13] and in cases Shaowu et al. reported in 2014, internal fixation with plate was performed on clavicles in addition to bone curettage with biopsy [14].

In the present case, the patient was given an explanation of the treatment method, and after that, consent was sought and proceed bone curettage and autogenous iliac bone graft. Callus formation and periosteal reaction around the curettage site were found on the follow-up simple radiographic examination. Radiologic findings of bone union on graft site were observed at 10 months postoperative follow-up.

4. Conclusion

The authors reported a very rare case of LCH in adult in clavicle. On account of frequent involvement sites and ages of LCH, solitary tumorous lesion in an adult’s clavicle can be easily mistaken for other diagnoses such as eosinophilic granuloma and so forth. Most of the solitary tumorous lesions in clavicle in adults call for various differential diagnoses. Therefore, Langerhans` Cell Histiocytosis should be considered in the diagnosis of a adult patient with a clavicle mass.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

This Work (2018R1D1A1B07049185) was Supported by the Basic Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education Science and Technology.

Ethical approval

This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Gyeongsang National University Hospital.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-chief of this journal.

Author contribution

MG carried out medical management and the writing of the manuscript. DC arranged the data needed to wrist a manuscript. JS performed the histological examination of the patient. DH has given expert opinion and final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Registration of research studies

-

1

Name of the registry:

-

2

Unique identifying number or registration ID:

-

3

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):

Guarantor

The authors declare that they guarant responsibility.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank our patient for allowing us to publish this case report.

Contributor Information

Myung-Geun Song, Email: piano10000@naver.com.

Dae-Cheol Nam, Email: ortho87@naver.com.

Jong Sil Lee, Email: jongsil25@gnu.ac.kr.

Dong-Hee Kim, Email: dhkim8311@gnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Egeler R.M., D’Angio G.J. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J. Pediatr. 1995;127(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howarth D.M., Gilchrist G.S., Mullan B.P., Wiseman G.A., Edmonson J.H., Schomberg P.J. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer. 1999;85(10):2278–2290. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2278::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harmon C.M., Brown N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic review and molecular pathogenetic update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015;139(10):1211–1214. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0199-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azouz E.M., Saigal G., Rodriguez M.M., Podda A. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr. Radiol. 2005;35(2):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A.J., Orgill D.P. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilpatrick S.E., Wenger D.E., Gilchrist G.S., Shives T.C., Wollan P.C., Unni K.K. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X) of bone. A clinicopathologic analysis of 263 pediatric and adult cases. Cancer. 1995;76(12):2471–2484. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951215)76:12<2471::aid-cncr2820761211>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stull M.A., Kransdorf M.J., Devaney K.O. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Radiographics. 1992;12(4):801–823. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.12.4.1636041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Demellawy D., Young J.L., de Nanassy J., Chernetsova E., Nasr A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a comprehensive review. Pathology. 2015;47(4):294–301. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapoor S., Tiwari A., Kapoor S. Primary tumours and tumorous lesions of clavicle. Int. Orthop. 2008;32(6):829–834. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0397-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith J., Yuppa F., Watson R.C. Primary tumors and tumor-like lesions of the clavicle. Skeletal Radiol. 1988;17(4):235–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren K., Wu S., Shi X., Zhao J., Liu X. Primary clavicle tumors and tumorous lesions: a review of 206 cases in East Asia. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2012;132(6):883–889. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satter E.K., High W.A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a review of the current recommendations of the Histiocyte Society. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2008;25(3):291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Udaka T., Susa M., Kikuta K., Nishimoto K., Horiuchi K., Sasaki A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the clavicle in an adult: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Oncol. 2015;8(3):426–431. doi: 10.1159/000441415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S., Zhang W., Na S., Zhang L., Lang Z. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the clavicle: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93(20):e117. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.