Significance

We present a coordinated petrologic, mineral chemistry, and multi-isotopic investigation of individual chondrules to further elucidate the origins and formation histories of planetary materials. We show chondrules from certain meteorites that accreted in the outer Solar System contain an assortment of both inner and outer Solar System material, as well as previously unidentified material. The outward transport of inner Solar System material places important constraints on dynamical models, as outward transport in the disk was thought possible only if significant barriers (e.g., Jupiter) to radial transport of materials do not exist. We show this “barrier” is either not completely impermeable to transport of millimeter-sized materials or additional mechanisms are required to transport materials to the outer Solar System.

Keywords: chondrules, bulk meteorites, isotope anomalies, disk transport, disk mixing

Abstract

Dynamic models of the protoplanetary disk indicate there should be large-scale material transport in and out of the inner Solar System, but direct evidence for such transport is scarce. Here we show that the ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O systematics of large individual chondrules, which typically formed 2 to 3 My after the formation of the first solids in the Solar System, indicate certain meteorites (CV and CK chondrites) that formed in the outer Solar System accreted an assortment of both inner and outer Solar System materials, as well as material previously unidentified through the analysis of bulk meteorites. Mixing with primordial refractory components reveals a “missing reservoir” that bridges the gap between inner and outer Solar System materials. We also observe chondrules with positive ε50Ti and ε54Cr plot with a constant offset below the primitive chondrule mineral line (PCM), indicating that they are on the slope ∼1.0 in the oxygen three-isotope diagram. In contrast, chondrules with negative ε50Ti and ε54Cr increasingly deviate above from PCM line with increasing δ18O, suggesting that they are on a mixing trend with an ordinary chondrite-like isotope reservoir. Furthermore, the Δ17O-Mg# systematics of these chondrules indicate they formed in environments characterized by distinct abundances of dust and H2O ice. We posit that large-scale outward transport of nominally inner Solar System materials most likely occurred along the midplane associated with a viscously evolving disk and that CV and CK chondrules formed in local regions of enhanced gas pressure and dust density created by the formation of Jupiter.

Chemical and isotopic signatures of primitive meteorites provide a powerful means to trace the earliest history of planet formation in our Solar System (1). Nucleosynthetic anomalies in 50Ti and 54Cr have been identified among major meteorite classes that distinguish planetary materials into two groups, noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorites (2–5). Bulk meteorites and their components also show a significant variability in the mass-independent fractionation of O isotopes, which could have resulted from photochemical reactions that occurred heterogeneously across the protoplanetary disk (6). Several other isotope systems have now been found to show a similar dichotomy between noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorites and, collectively, may not be easily explained by thermal processing of isotopically anomalous presolar carriers or addition of early-formed Ca- and Al-rich inclusions (CAIs) (7). Instead, most studies have proposed that the dichotomy was caused by spatial differences in isotopic signatures during the earliest stage of disk evolution (5, 7, 8), such that the isotopic signatures of noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorites represent those of inner and outer disk materials, respectively.

Nucleosynthetic anomalies in 50Ti and 54Cr associated with bulk meteorites reflect the average composition of solids that were accreted onto their parent asteroids from local regions within the disk. However, local regions within the disk may actually be composed of solids with diverse formation histories and, thus, distinct isotope signatures, which can only be revealed by studying individual components in primitive chondritic meteorites (e.g., chondrules). Chondrules are millimeter-sized spherules that evolved as free-floating objects processed by transient heating in the protoplanetary disk (1) and represent a major solid component (by volume) of the disk that is accreted into most chondrites. The nucleosynthetic anomalies in 50Ti and 54Cr of individual chondrules are, in most cases, similar to those of their bulk meteorites (9–12), which suggests a close relation between the regions where chondrules formed and where they accreted into their asteroidal parent bodies. However, exceptions to this observation are chondrules in CV chondrites, which display the entire range of 50Ti and 54Cr observed for all bulk meteorite groups (9, 11). Previous Cr isotope studies that have observed this larger isotopic range in CV chondrules have proposed that these chondrules or their precursor materials originated from a wide (not local) spatial region of the protoplanetary disk and were transported to CV chondrite accretion regions (9). In contrast, Ti isotope studies have suggested that the wide range of isotope anomalies observed in individual CV chondrules could be explained by the admixture of CAI-like precursor materials with highest nucleosynthetic 50Ti and 54Cr anomaly, which are abundant in CV chondrites (11).

Resolving these two competing interpretations would significantly improve our understanding of the origin of the isotopic dichotomy observed for bulk meteorites and provide constraints on the disk transport mechanism(s) responsible for the potential mixing of material with different formation histories. However, in earlier studies, Ti and Cr isotopes were not obtained from the same chondrules, which is required to uniquely identify their precursor materials and associated formation histories. Also absent in earlier studies is documentation of the properties (petrographic and geochemical) of individual chondrules that provide a valuable aid in interpreting Ti and Cr isotope data. Thus, we designed a coordinated chemical and Ti-Cr-O isotopic investigation of individual chondrules extracted from Allende (CV) and Karoonda (CK) chondrites (3). While the 50Ti and 54Cr of chondrules tracks the average composition of solids, the analyses of O isotopes and mineral chemistry of major Mg silicates (olivine and pyroxene) is useful to distinguish chondrules that are similar to those in ordinary chondrites (13–16) as well as precursor materials that may have formed in regions of the disk with variable redox conditions or with distinct proportions of anhydrous dust versus H2O ice (17). A significant number of high-precision Ti and Cr isotope analyses of bulk meteorites were also obtained for both carbonaceous and noncarbonaceous meteorites to help define the bulk meteorite 50Ti-54Cr systematics of known planetary materials.

Results

Bulk Meteorite 50Ti and 54Cr Isotopes.

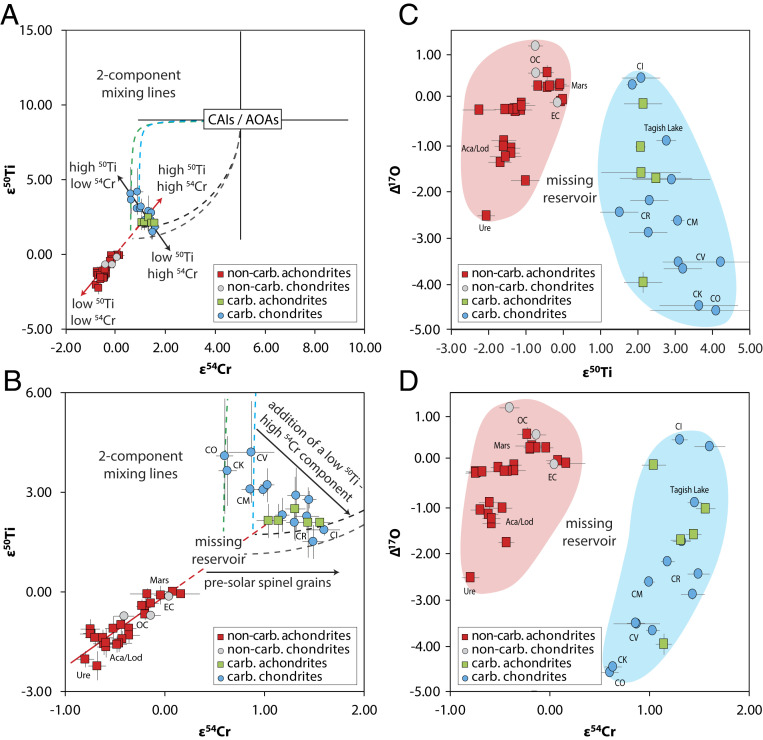

We obtained analyses of Ti and Cr isotopic compositions (reported as ε50Ti and ε54Cr, which are parts per 10,000 deviations from a terrestrial standard) for 30 bulk meteorites, all of which have mass-independent O isotope analyses reported as Δ17O [a vertical deviation from the terrestrial fractionation line in parts per 1,000 (18)] previously reported (Dataset S1 and Fig. 1). The data clearly define two distinct isotopic groups: 1) noncarbonaceous meteorites, including enstatite chondrites (ECs), ordinary chondrites (OCs), and most differentiated meteorites known as achondrites (e.g., Moon, Mars, Vesta, angrites, ureilites, acapulcoites, lodranites, and winonaites) and 2) carbonaceous meteorites [including carbonaceous chondrites and several ungrouped achondrites (19)]. These two groups display orthogonal trends and are isolated from each other by a large area in ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O isotope space that is devoid of any bulk meteorite compositions (shown as “missing reservoir” in Fig. 1). This paucity of samples remains even after including analyses from our expanded dataset. Previous work (2) calculated a linear regression through the noncarbonaceous meteorites using the data available at the time, which intersected the field defined by carbonaceous meteorites at approximately the composition of CI chondrites, an endmember of the carbonaceous meteorite field. However, when a linear regression is calculated through our expanded set of ε50Ti and ε54Cr of noncarbonaceous meteorites, the extrapolation of the regression intersects the middle of the bulk carbonaceous meteorite composition region, close to the CM chondrites and their immediate neighbors (Fig. 1B). This is markedly different from the previous study that proposed an intersection at one of the endmember locations of the carbonaceous region, near CI chondrites (2).

Fig. 1.

The ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O isotopic compositions of bulk carbonaceous and noncarbonaceous meteorites. (A,B) Data for ε50Ti and ε54Cr from this study are shown in Dataset S1. Literature data for ε50Ti and ε54Cr are from refs. 19–25. (C, D) Literature Δ17Ο data are from refs. 26–42. Error bars are either the internal 2 SE or external 2 SD, whichever is larger. Note that noncarbonaceous meteorites are characterized by a strong positive linear correlation in the ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O isotope space, while carbonaceous meteorites are characterized by a strong negative correlation in ε50Ti-ε54Cr (A, B) and ε50Ti-Δ17O (C) isotope spaces but a positive correlation in 54Cr-Δ17O (D) isotope space. Also shown (A) is the average ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic composition of “normal” CAIs. Error bars represent the overall range of reported normal CAI values. Dashed blue and green lines (A, B) represent a two-component mixing line between the average value of “normal” CAIs and extension of the noncarbonaceous line. Dashed black and gray lines represent a two-component mixing line between the average value of AOAs and extension of the noncarbonaceous line. The red line represents a linear regression through noncarbonaceous meteorites, ostensibly inner Solar System materials (gray circles and red squares), calculated using Isoplot version 4.15. Note that the linear regression through noncarbonaceous meteorites intersects carbonaceous chondrite field near CM chondrites ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotope space (A, B). The “missing reservoir” denotes the region between noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorite groups that lacks any reported bulk meteorite data. (B) Zoomed-in view of A. Legend abbreviations: carb., carbonaceous; noncarb., noncarbonaceous; EC, enstatite chondrite; OC, ordinary chondrite; Ure, ureilite; Aca/Lod (acapulcoite/lodranite).

Mineral Chemistry and Textures of Selected Chondrules.

The ferromagnesian chondrules studied here include porphyritic olivine (PO), porphyritic olivine-pyroxene (POP), and barred olivine (BO). Additionally, one chondrule from Allende is an Al-rich chondrule. The Mg# (defined as Mg# = [MgO]/[MgO + FeO] in molar percent) of Allende chondrules spans from 83 to 99.5 (Dataset S2). The olivine Cr2O3 content in the Allende chondrules in this study is mostly greater than 0.1%, which is different from the typically <0.1% Cr2O3 reported for Allende chondrules. Following the method of ref. 43, the average olivine Cr2O3 contents for seven Allende chondrules with forsterite (Mg2SiO4) content Fo <97 is calculated to be 0.20 ± 0.34 wt % (2 SD) (Dataset S6), which is similar to unequilibrated ordinary chondrites (UOCs) with subtype 3.1. It is likely that the large chondrules selected in this study (diameters of 2 to 3 mm; SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S3) were less affected by thermal metamorphism than typical Allende chondrules. Three BO chondrules have Mg# 83 to 90, which are rare in CV chondrites (14, 16, 44), though they are similar to several FeO-rich BO chondrules studied for O isotopes by ref. 45. The Al-rich chondrule (Allende 4327-CH8) contains abundant Ca-rich plagioclase and zoned Ca-pyroxene. Chondrules in Karoonda are all olivine-rich and show homogeneous olivine compositions (Datasets S2 and S6). Their primary Mg# was subsequently modified during parent body metamorphism due to fast Fe–Mg exchange in olivine, though original porphyritic or barred olivine textures were preserved (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S4).

Multi-isotope Systematics of Individual Chondrules.

The ε50Ti and ε54Cr analyses of individual chondrules in CV and CK chondrites show a large range from –2.3 to +3.6 and from –0.7 to +1.2, respectively (Datasets S2 and S3). These observed ranges are consistent with previous studies (2, 9–12) and span the entire range of isotopic compositions exhibited by bulk meteorite measurements. The Al-rich chondrule, Allende 4327-CH8, has an ε50Ti value of +8.4 ± 0.3, similar to the ε50Ti observed in CAIs (2, 46). The ε54Cr values of chondrules from CR, L, and EH chondrites show a narrow range within each meteorite and are consistent with those of bulk meteorites (Dataset S3), in contrast to the results from CV and CK chondrites.

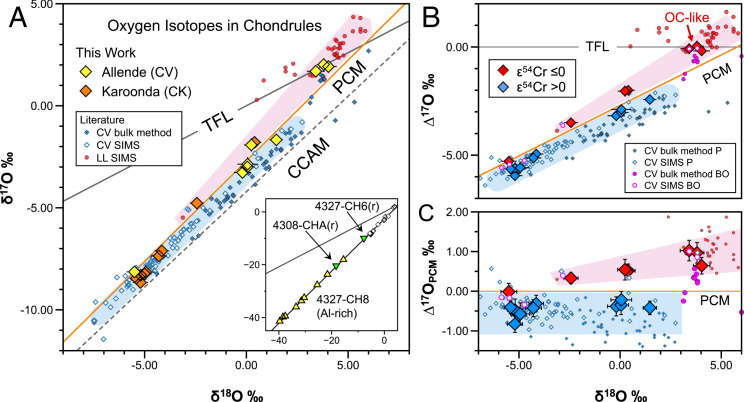

Most chondrules (excluding Allende 4327-CH8) are internally homogenous with Δ17O varying from –5‰ to 0‰ (Dataset S2). On a three-isotope diagram (δ17O versus δ18O in the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water scale where δ represents deviation from a standard in parts per 1,000; Fig. 2A), individual chondrules plot close to the primitive chondrule mineral (PCM) line (47) and are generally consistent with chondrules in CV chondrites (14, 16, 44, 45, 48, 49). Several FeO-rich BO chondrules plot very close to the terrestrial fractionation line, which is in good agreement with similar BO chondrules studied in refs. 16, 44, 45. Their O isotope ratios are similar to FeO-rich chondrules in Kaba by ref. 14 and Y-82094 (an ungrouped carbonaceous chondrite) by ref. 13, which are considered to have ordinary chondrite chondrule-like O isotope ratios (50). The Al-rich chondrule Allende 4327-CH8 is the only chondrule in this study that showed significant internal heterogeneity in O isotopes, with δ17,18O values approaching ∼ –40‰ (Fig. 2 A, Inset), the lowest values of which are close to those observed for CAIs and amoeboid olivine aggregates (AOAs) (51). Fig. 2 shows that, in detail, many chondrules in this study as well as CV chondrules in the literature plot slightly below the PCM line, while others including FeO-rich BO chondrules plot above the PCM line and trend toward ordinary chondrite chondrule data (50). This small difference becomes a more notable division when chondrules are sorted by their ε50Ti or ε54Cr (Fig. 2 B and C); chondrules above the PCM line all have negative ε54Cr, and those below the PCM line have positive ε54Cr (Fig. 2 B and C). It should be noted, however, that this division about the PCM line cannot be universally applied to the bulk meteorites data as ureilites, for example, which have negative 50Ti and 54Cr isotopic compositions, plot well below the PCM line.

Fig. 2.

Oxygen isotope ratios of chondrules from Allende and Karoonda meteorites with known 54Cr and 50Ti isotope anomalies. (A) Mean oxygen isotope ratios of individual chondrules from multiple SIMS analyses (Dataset S2). Terrestrial fractionation line (TFL; ref. 18), carbonaceous chondrite anhydrous mineral line (CCAM; ref. 52) and PCM line (47) are shown as reference. Oxygen isotope analyses of individual chondrules using bulk methods for CV (45, 48, 49), using SIMS for CV (14, 16, 44), and LL (50) are shown. Error bars are at 95% confidence level. Blue and pink shaded areas represent two linear trends among Allende and Karoonda chondrules, those that plot parallel to the PCM line along with the majority of literature CV chondrule data (blue) and those that plot toward LL chondrule data above the PCM line (pink). (Inset) The 16O-rich relict olivine grains in Allende 4327-CH6 and 4308-CHA chondrules (green downward triangles) and individual data from Al-rich chondrule Allende 4327-CH8 (yellow upward triangles) that show heterogenous oxygen isotope ratios (Dataset S4). For simplicity, only TFL and PCM line are shown in the inset. (B) Mass independent fractionation ∆17O (= δ17O – 0.52 × δ18O) of individual chondrules in Allende and Karoonda plotted against δ18O. Chondrules with negative ε54Cr (red diamonds) plot above the PCM line toward LL chondrule data (pink shaded region), while those with positive ε54Cr (blue diamonds) plot slightly below and parallel to the PCM line, along with majority of CV chondrules in the literature (blue shaded region). Three BO chondrules plotted on TFL are regarded as ordinary chondrite-like chondrules. Literature data of BO chondrules in CV (open and filled pink circles using bulk methods and SIMS) often show oxygen isotope ratios above the PCM line. (C) Deviation of ∆17O relative to the PCM line (∆17OPCM = δ17O – 0.987 × δ18O + 2.70). Chondrules with positive ε54Cr show a constant offset from the PCM line (∼–0.5‰), indicating that they are on the slope ∼1.0 in the oxygen three-isotope diagram. In contrast, chondrules with negative ε54Cr (and ε50Ti) increasingly deviate from the PCM line with increasing δ18O, suggesting that they are on the mixing trend with an ordinary chondrite-like isotope reservoir.

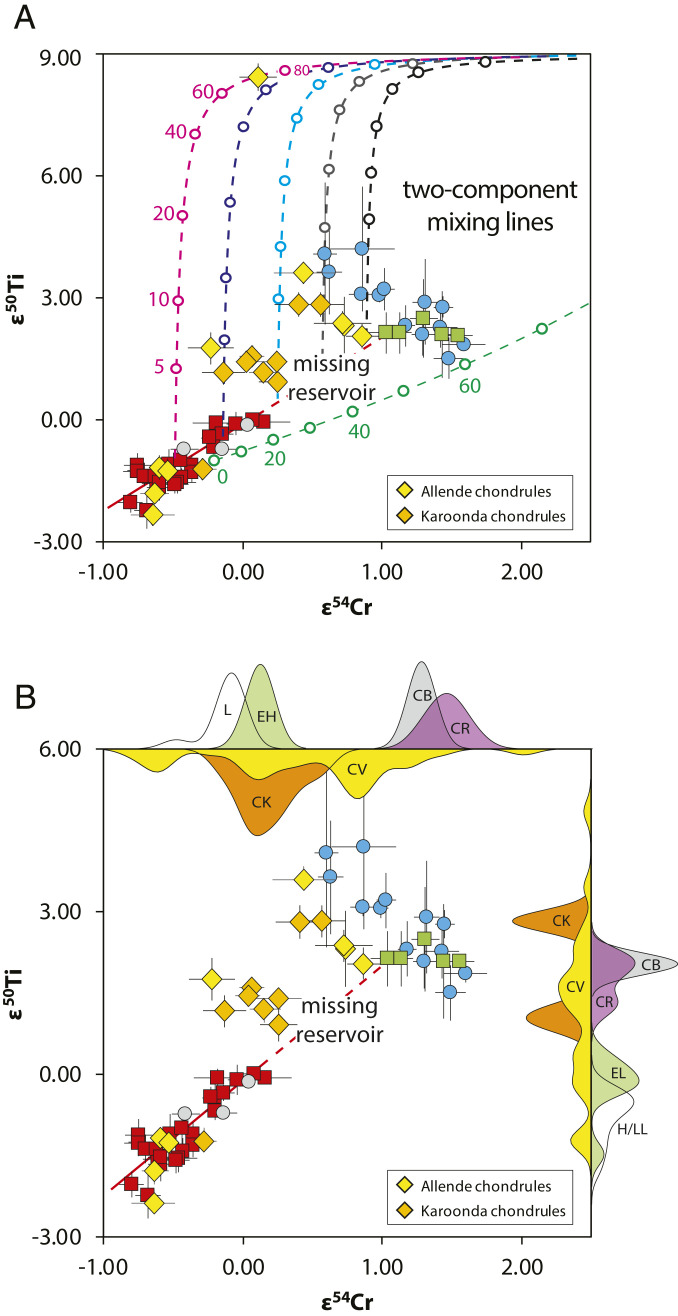

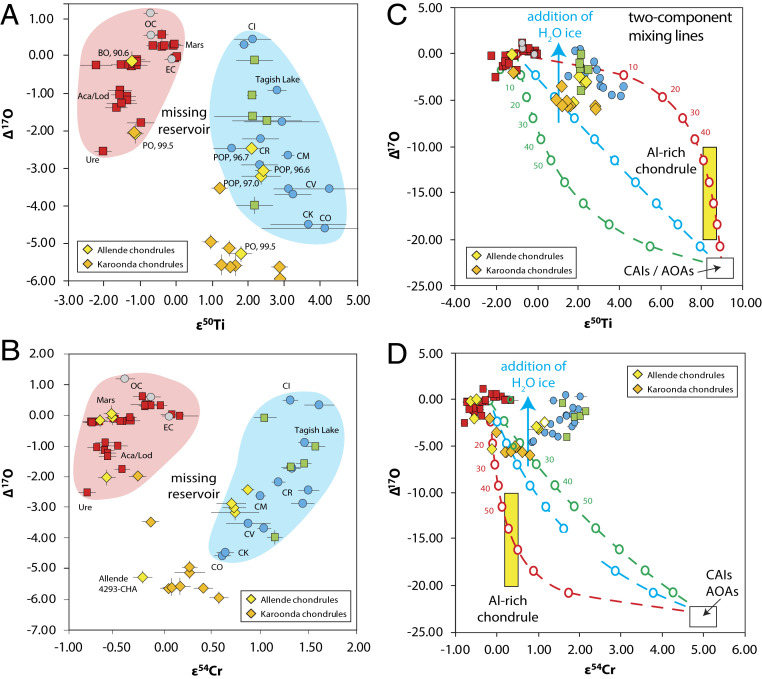

By combining Ti-Cr-O isotope systems of Allende and Karoonda chondrules (Figs. 3 and 4), these chondrules are grouped into three general “clusters” that display distinct isotope signatures: 1) similar to bulk carbonaceous meteorites, 2) within noncarbonaceous meteorite field, and 3) near the missing reservoir with slightly positive ε50Ti ∼ +1 to 2, ε54Cr ∼ 0, and Δ17O ∼ –5‰. Such distinct groups cannot be identified from a single isotope system. Although the total ranges of ε50Ti and ε54Cr are slightly smaller for chondrules in Karoonda than those in Allende, both chondrule datasets vary similarly in multi-isotope systematics, suggesting that both Ti and Cr in the bulk chondrules and olivine O isotopes retained their primary isotope signatures even with the mild metamorphic conditions experienced by CK4 chondrites. The Al-rich chondrule (Allende 4327-CH8) shows an intermediate Ti and Cr isotopic composition, which may be caused by the mixing of CAI-like precursors in the chondrule (2), consistent with its Al-rich mineralogy and low δ18O and δ17O values approaching those of CAIs (Figs. 3A and 4 C and D).

Fig. 3.

The ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic compositions of individual chondrules. (A) The ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic compositions of bulk meteorites (Fig. 1) and individual chondrules from CV (Allende; yellow diamonds) and CK (Karoonda; orange diamonds) chondrites. Bulk meteorite symbols are the same as in Fig. 1. Error bars are either the internal 2 SE or external 2 SD, whichever is larger. Each of the multicolored dashed lines with tick marks represents a two-component mixing line between either the average value of “normal” CAIs (the five concave down curves) or AOAs with relatively low Ti/Cr ratios (the green semilinear curve) and members of the extended noncarbonaceous meteorite group (Fig. 1). Note that these mixing lines project to an endmember characterized by an inner Solar System noncarbonaceous composition that extends to and bridges the carbonaceous chondrite field, filling the “missing reservoir” shown in Fig. 1. (B) Zoomed-in view of A. Also shown are kernel density plots of individual chondrules including our data here as well as literature data (2, 9–12) constructed using the MATLAB ksdensity function with bandwidths of 0.2 and 0.1 for ε50Ti and ε54Cr isotopic compositions, respectively. Note the limited range in ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic compositions of individual chondrules from CR, CB, enstatite, and ordinary chondrites (outside Fig. 2B axes) relative to chondrules from CV and CK chondrites (inside Fig. 2B axes). Data obtained from this study are shown in Datasets S1–S3.

Fig. 4.

The ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O isotopic compositions of bulk meteorites and individual chondrules. The ε50Ti-Δ17O (A and C) and ε54Cr-Δ17O (B and C) isotope systematics of bulk meteorites (see Fig. 1) and individual chondrules from CV (Allende) and CK (Karoonda) chondrites. Color symbols are the same as in Fig. 1. Error bars are either the internal 2 SE or external 2 SD, whichever is larger. Several individual chondrules are characterized by isotopic compositions that plot within the missing reservoir or outside the regions defined by noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorites. (C and D) Zoomed-out views of A and B. The Δ17O isotopic composition of the Al-rich chondrule from Allende (4327-CH8) is variable S4 (Dataset S4) and therefore displayed as a yellow bar covering the entire range. Also labeled is Allende chondrule 4293-CHA. The red curve represents mixing with a “typical” CAI Ti/Cr ratio as one endmember (though this could also be an AOA depending on what that AOA is actually composed of). The blue curve represents mixing with a “typical” AOA Ti/Cr ratio as one endmember (though this could also be a CAI depending on what that CAI is actually composed of). The green curve represents mixing with an “olivine-rich” AOA with elevated Cr contents as one endmember. These three curves show that the vast majority of our “intermediate” chondrule data can be explained by mixing “average” noncarbonaceous material with either CAIs or AOAs, while the rest of our chondrules could just be reprocessed carbonaceous or noncarbonaceous materials.

Discussion

Mixing Model and the Missing Reservoir.

The distinct grouping of noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous meteorites in ε50Ti-ε54Cr space was proposed to result from the addition of refractory inner Solar System dust such as CAIs to CAI-free outer Solar System matrix, as represented by CI chondrites (2). This two-component mixing (2) is predicated on a regression line intersecting the carbonaceous meteorite trend at the bulk, CAI-free CI chondrite composition (2). However, with our newly acquired bulk meteorite data (Dataset S1), Fig. 1 reveals that an updated linear extrapolation of only the noncarbonaceous meteorites intersects the middle of the region defined by the bulk carbonaceous meteorites, close to CM chondrites and their immediate neighbor, but not CI chondrites, which was a requirement of previous models (2).

Importantly, theoretical mixing trajectories of noncarbonaceous endmembers with CAI-like dust (2) do not allow the resulting isotopic compositions for bulk carbonaceous meteorites to plot below the linear extrapolation of the noncarbonaceous meteorites (Figs. 1 and 3). Therefore, adding CAI-like components to the linear noncarbonaceous trend (2, 11) cannot account for the entire carbonaceous chondrite trend (which includes most CR chondrites, CI and CB chondrites, and Tagish Lake). Rather, carbonaceous members that plot below the noncarbonaceous extension line (Figs. 1 and 3) require mixing either with AOA-like materials that are characterized by positive ε50Ti and ε54Cr values (e.g., forsterite-bearing CAIs like SJ101; ref. 53) with relatively low Ti/Cr ratios or a hypothetical presolar component characterized by a relatively low ε50Ti and high ε54Cr values. Future work should continue to search for possible presolar materials that may be characterized by depleted ε50Ti and enriched ε54Cr signatures. This component of the carbonaceous meteorite trend may also reflect the addition of Cr-rich spinel grains that are characterized by large excesses in ε54Cr (e.g., ref. 54) to materials that lie on the extension of the noncarbonaceous line. In this scenario, bulk meteorite values would shift horizontally (because spinel contains a negligible amount of Ti) to this region of carbonaceous materials.

The wide range in the isotopic composition of individual chondrules from Allende and Karoonda demonstrates that these chondrules formed from a variety of materials including noncarbonaceous meteorite-like dust, carbonaceous meteorite-like dust, CAI- or AOA-like dust, and dust from a reservoir with intermediate ε50Ti and ε54Cr values that is not apparent from the analysis of only bulk meteorites (Figs. 1, 3, and 4). A single Al-rich chondrule (4327-CHA) is a prime example of a mixture between (75%) CAIs and (25%) noncarbonaceous materials, characterized by excesses in both ε50Ti and ε54Cr isotopic compositions of 8.42 and 0.11, respectively (Fig. 3A). Significant addition of a CAI precursor component to this chondrule is also evident from abundant 16O-rich relict olivine grains in this Al-rich chondrule that show variable Δ17O values from −10‰ down to −21‰, similar to those of CAIs (Figs. 2 A, Inset and 4 C and D and Dataset S4). Mixing between CAIs and less refractory materials is also consistent with observations of relict CAIs inside chondrules (55–57) and the extremely low Δ17O values of some chondrule spinel grains (13, 58, 59) as well as the texture and chemical composition of relict grains with surrounding chondrule glass (60, 61).

Several chondrules from both CV and CK chondrites that have intermediate ε50Ti and ε54Cr values and lie slightly above the linear extrapolation of the noncarbonaceous field (e.g., Fig. 3A) may reflect two-component mixing between either CAIs or AOA-like precursors and the extended noncarbonaceous reservoir (Fig. 3A). AOAs are inferred to have formed from the same isotopic reservoirs as CAIs (e.g., ref. 51) but are less refractory than CAIs, meaning lesser amount of Ti but more Cr than CAIs (62). The mixing trajectory with AOAs should result in a mixing line with a lower or even an opposite curvature compared to that of CAIs depending in the exact nature of the Ti/Cr ratios (Figs. 1 A and B, 3A, and 4 C and D). Although the ε50Ti and ε54Cr values of AOAs have not been measured, it is reasonable to assume AOAs have ε50Ti and ε54Cr composition similar to that of CAIs (including forsterite-bearing CAIs; 53) given that AOAs and CAIs are observed to have similar Δ17O values (51). AOAs are abundant in CV chondrites and are often considered to be precursors of chondrules that contain 16O-rich relict olivine (e.g., ref. 63). Based upon the observations that the majority of chondrules in the CV chondrites plot on mixing lines between materials of non-carbonaceous composition and the more refractory CAI and AOA-like compositions (Figs. 3 and 4), it can be inferred that the vast majority of CV chondrite chondrules are representative of mixtures of at least two distinct precursor reservoirs.

Thermal Processing and Unmixing?

Our results indicate the noncarbonaceous trend is unlikely related to thermal processing (often referred to as “unmixing”) of isotopically distinct dust (2, 9). For thermal processing to result in the linear trend observed for the noncarbonaceous meteorites, the elemental Ti/Cr ratios of the dust being processed would have to remain unfractionated. However, Ti and Cr are characterized by very different volatilities and carrier phases, and therefore thermal processing of dust is unlikely to result in the linear trend in ε50Ti and ε54Cr space. Bulk carbonaceous and noncarbonaceous materials also display a continuum in their Δ17O values, that is, their Δ17O values overlap each other and lack any indication of clustering into distinct Δ17O groups (Fig. 1 C and D). This demonstrates that, while the variability observed in the ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic compositions of bulk meteorites is due to dust that accreted to form planetesimals, the Δ17O values reflect additional components that did not significantly affect ε50Ti-ε54Cr isotopic compositions (e.g., H2O ice, hydrated minerals, and organics).

Chondrule Formation Environment.

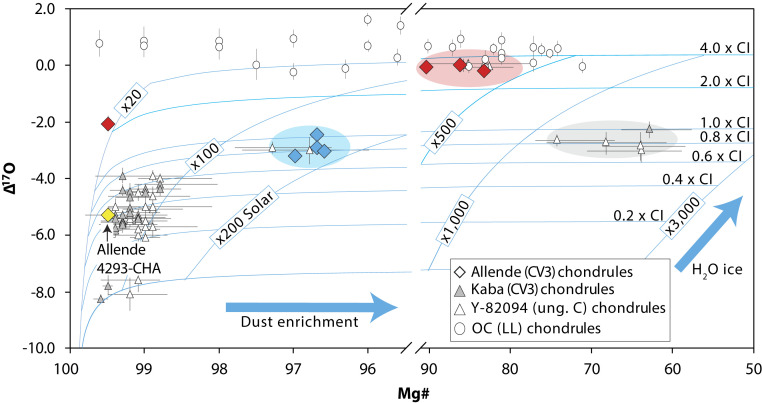

Allende chondrules show a range of diversity in both Mg# and Δ17O (Fig. 5 and Datasets S2 and S4) similar to those of CV and other carbonaceous chondrites, such as Y-82094 and Kaba (13, 14). By adapting a mass balance model for chondrule O isotope under the existence of 16O-poor H2O ice in carbonaceous chondrite-forming regions (14, 17), the formation environment of each chondrule can be estimated. One Allende chondrule (Allende 4293-CHA) is characterized by a Mg# ∼ 99.5 and Δ17O ∼ –5.3‰ (Fig. 5), which corresponds to an environment with relatively low dust enrichment and an abundance of 16O-poor H2O ice associated with its precursor materials (≤100 times Solar and ≤0.6 times CI, respectively; ref. 14). Chondrules with high Mg# (>98) and Δ17O ∼ –5‰ are the most common type of chondrules in CV chondrites (14, 16) (also in SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The same chondrule (Allende 4293-CHA) has isotopic values of ε50Ti =1.8 and ε54Cr = –0.2, which fall between the noncarbonaceous and carbonaceous groups (Fig. 3), where no bulk meteorite data were previously observed. Chondrules with positive ε50Ti and ε54Cr values, similar to bulk carbonaceous meteorites, have lower Mg# ∼ 97 and Δ17O ∼ –3‰ (Fig. 5), consistent with a formation environment characterized by higher abundances of H2O ice (∼0.8 times CI) with relatively higher dust enrichments (100 to 200 times Solar).

Fig. 5.

Oxygen isotope ratios of Allende chondrules versus their Mg#. Chondrules from Allende (CV3) (this study), Kaba (CV3) (14), ungrouped Y-82094 (13), and (LL) ordinary chondrites (50) Bishinpur, Semarkona, and Krymka are plotted. Curves are from the O isotope mixing model with variable ratios of water ice enhancement factors relative to CI chondritic proportions and under variable dust enrichment factors relative to Solar abundance. See Methods for more details about the mixing model. Allende chondrule data with noncarbonaceous, carbonaceous, or missing reservoir ε50Ti- ε54Cr signatures are represented by red, blue, and yellow diamonds, respectively. These chondrules as well as majority of chondrules from other CV3 chondrites plot along the model curves, suggesting that they formed in the environments with variable 16O-poor water ice and dust enrichment.

Other Allende chondrules with higher Δ17O (–2 to 0‰) are those with negative ε50Ti and ε54Cr values. They plot above the model curve for the CI chondritic H2O ice abundance (4 times CI) and at low to relatively high dust enrichments (∼20 times Solar for Allende 4327-CH6 and approaching ∼500 times Solar for BO chondrules). However, their O isotopic compositions are fractionated above the PCM line (Fig. 2 B and C) toward the region occupied by ordinary chondrites (50), which may represent mixing with ordinary chondrite-like dust, but not with 16O-poor H2O ice as in the model assumption. If these chondrules were formed in the environments similar to those of ordinary chondrite chondrule formation, the mass balance model in Fig. 5 may not be relevant to estimate the ice enhancement factor and would have higher dust-enrichment factors than the estimates (Methods).

Radial Transport in the Protoplanetary Disk.

Our data suggest that CV and CK chondrites, which are interpreted to have accreted in the outer Solar System (5), collected materials that originated from a variety of Solar System reservoirs, as evidenced by the Ti and Cr isotopic composition of their constituent chondrules. It has been proposed that radial transport of materials from the inner to outer Solar System may occur in viscously evolving disks, where flow along the disk midplane (also known as meridional flow) transports inner Solar System dust to larger orbital distances (64–67), as far out as the Kuiper Belt, before slowly drifting back toward the Sun. The outward transport of inner Solar System dust in viscously evolving disks is only possible if significant barriers to radial transport of materials (e.g., gaps and pressure bumps) do not exist; for example, giant planets such as Jupiter have yet to grow to sufficient size to limit diffusive transport between the inner and outer Solar System along the disk midplane. Once Jupiter formed, inner Solar System dust previously transported to the outer Solar System could have become trapped while remaining inner Solar System materials would have been prevented from any further transport beyond Jupiter (64, 68, 69).

Jupiter Maintains the Great Isotopic Dichotomy.

In this scenario, if the inner Solar System had become devoid of CAIs [having been accreted onto the Sun or transported beyond Jupiter (64)], then meteorites like ordinary and enstatite chondrites forming inside of Jupiter’s orbit would primarily accrete material defining a very narrow range in their ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O-Mg# compositions (e.g., ordinary and enstatite chondrite chondrules). The dust in this region would be characterized by deficits in ε50Ti and ε54Cr that is accompanied by a relatively high but still limited range in Δ17O (similar to chondrules from ordinary chondrites). Alternatively, the relatively high Δ17O values could have resulted from interactions with H2O ice transported inward prior to the formation of Jupiter.

In contrast, carbonaceous chondrites meteorites that formed just outside of Jupiter’s orbit (e.g., CV and CK parent bodies) could have accreted inner Solar System dust, CAI- and/or AOA-like dust, and less refractory outer Solar System material (64, 70). If this is correct, chondrules that formed from dust in this region would then display a very broad range in their observed ε50Ti-ε54Cr-Δ17O isotopic compositions, for example as seen in the Allende and Karoonda chondrules, where the resulting composition depends on the relative proportion of inner versus outer Solar System materials incorporated into each individual chondrule. A pressure maximum just outside the orbit of Jupiter could also have trapped locally variable amounts of 16O-poor H2O ice, resulting in chondrule formation under variable redox conditions. Incorporation of this H2O ice during chondrule formation would not only increase the bulk Δ17O value of a chondrule but also lower its bulk Mg#, due to oxidation of Fe to FeO (Fig. 5).

Permeable Barrier and Crossing the Gap.

Al-Mg ages of ordinary chondrite-like chondrules in Acfer 094 (a most primitive carbonaceous chondrite) suggest these chondrules formed in inner disk regions 1.8 My after CAIs and more than 0.4 to 0.8 My prior to the rest of the chondrules in the same meteorite (15). The discovery of noncarbonaceous-like chondrules and their mixing with CAIs and/or AOAs in CV chondrites in this study, together with chondrules from Acfer 094, collectively suggest transport from the inner to the outer Solar System was a far more frequent and protracted processes. Outward transport is not limited to just CAIs and AOAs at the earliest stages of disk evolution. This delayed timing (>1.8 My after CAIs) of outward transport of ordinary chondrite-like, inner Solar System material is interesting as it has been proposed that Jupiter formed in less than 1 My (8); if ordinary chondrite-like chondrules were transported from the inner to the outer Solar System after this time then it means either the formation of Jupiter did not create a barrier completely impermeable to outward flow along the midplane at this time (at least for materials of this size with diameters of ∼2 to 3 mm) or some material was transported above this barrier by disk winds. An alternative to gap permeability is that our understanding of chondrule chronology is in question due to potential heterogeneity of 26Al distribution in the early Solar System allowing age uncertainties up to two half-lives of 26Al (cf. figure 6 in ref. 19).

The dust farther out in the Solar System than CV and CK parent bodies displays a relatively narrow range in ε50Ti-ε54Cr, perhaps similar to that observed for CR chondrite chondrules (Fig. 3B; ref. 9 and this study). Chondrules from CR chondrites (17) also show systematically lower Mg# and higher Δ17O values than those in CV chondrites (14, 16), most likely due to enhancement of 16O-poor H2O ice in the outer Solar System. What distinguishes CR chondrites from other carbonaceous chondrites is that their parent body formed late, greater than 4 My after CAIs, as indicated from many chondrules with no resolvable 26Mg excess (70). Chondrite parent bodies in the inner disk were likely formed by ∼2.5 Ma (64), when transport of noncarbonaceous chondrules to the outer disk would have stopped. Therefore, it is likely that CR chondrite accreted largely carbonaceous chondrules of local origin after ∼4 Ma in the outer Solar System, and almost no noncarbonaceous chondrules accreted into the CR chondrite parent body.

Our results, which link Ti, Cr, and O isotope systematics with the mineral chemistry of chondrules, reveal that, in the context of current dynamical models, large-scale outward transport of inner Solar System materials occurred in the protoplanetary disk, resulting in complex mixing of multiple components in the accretion region of some chondrite parent bodies.

Methods

Selections of Chondrules for Isotope Analyses.

Ten chondrules from Allende (CV3) and nine chondrules from Karoonda (CK4) were selected for coordinated isotopic (Cr, Ti, and O), petrologic, and mineral chemistry analyses (Datasets S2, S4, S5, and S6), together with 31 bulk rock carbonaceous and noncarbonaceous chondrites and achondrite meteorites (Dataset S1). An additional 28 chondrules from Allende (CV3), EET 92048 (CR2), Xinglongquan (L3), and Qingzhen (EH3) were analyzed for Cr isotopes (Dataset S3), which include three Allende chondrules that were also analyzed for Ti isotopes (Dataset S2). The mean diameters of chondrules in CV and CK chondrites are typically ∼900 µm and indistinguishable between CV and CK (71). For the purpose of obtaining enough Cr and Ti for isotopic analyses, large Allende chondrules with diameters of 1.5 mm to 3 mm were used. Diameters of Karoonda chondrules used in this work are also relatively larger than mean diameters, from 1 mm to 1.5 mm. While both Allende and Karoonda meteorites experienced mild thermal metamorphism in their parent bodies with petrologic types of 3.6 and 4, respectively, both Cr and Ti isotopes in these relatively large chondrules should be preserved within each chondrule against diffusional exchange in their parent bodies. All of these chondrules were scanned individually at high resolution using computed tomography at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. The selected chondrules were broken in two; one half was mounted in an epoxy thick section and the other half (3 to 27 mg) was used for Cr and Ti isotope analyses.

Major Element Analyses.

Electron microprobe analysis (EPMA) maps were acquired at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) using epoxy sections for 19 chondrules in Allende and Karoonda (Datasets S2 and S6). Additional data are curated as part of the AMNH meteorite collection (http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/6952). X-ray mapping, and analyses of silicates and metal grains were performed for 19 chondrules in Allende and Karoonda using the five-spectrometer CAMECA SX100 electron probe microanalyzer at AMNH. Maps 512 × 512 pixels in size were acquired for Na, Mg, Al, Si, S, Ca, Fe, and Ni, as well as the back-scattered electron signal, in stage mode with 1-µm beam, 3- to 5-µm step, and typically 20-ms dwell time per pixel. Combined elemental maps with virtual colors, such as Mg-Ca-Al for red-green-blue, are examined and used to identify phases and their two-dimensional mode in each chondrule, including olivine, high-Ca and low-Ca pyroxene, feldspar, spinel, mesostasis, metal, and sulfide.

Ti and Cr Isotope Analyses.

Material for bulk isotopic analyses were prepared from interior, fusion-crust free chips of each sample. Interior chips ranging in mass from 10 to 100 mg were gently crushed and homogenized in an agate mortar and pestle. An aliquot (ranging from 10 to 30 mg for bulk meteorites and 3 to 27 mg for chondrules) of the homogenized powders were placed in polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) Parr capsules along with a 3:1 mixture of ultraclean HF:HNO3. The PTFE capsule was placed into a stainless-steel jacket and heated in an oven at 190 °C for 96 h. This high-temperature pressure dissolution procedure ensures digestion of all phases, including refractory phases such as chromite and spinel. After dissolution, the sample solution was dried down and treated by alternating 6 M HCl and concentrated HNO3 to break down any fluorides formed during the dissolution process. The sample was then brought back up in 1 mL of 6 M HCl for the Cr separation chemistry using the procedure previously described by ref. 72. This chemical separation procedure utilizes a sequential three-column procedure (one anion resin column followed by two cation resin columns). After Cr was removed from the sample matrix, the remaining material were then processed through a sequence of columns to isolate Ti following the procedure described by ref. 73. The Ti yields after processing through the entire column procedure were >98%. All chemical separation was completed in a clean laboratory facility at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis).

Chromium isotopic ratios were determined using a Thermo Triton Plus thermal ionization mass spectrometer at UC Davis. Purified Cr was loaded onto outgassed tungsten filament with a load of 1 to 3 µg per filament depending on the amount of Cr available from the sample. The Cr was loaded across four filaments for a total load of 4 to 12 µg of Cr. The four sample filaments were bracketed by four filaments (two before and two after) loaded with the NIST SRM 979 Cr standard with the same loading amount as the sample. Each filament run consists of 1200 ratios with 8-s integration times. Signal intensity of 52Cr was set to 10, 8, or 6 V (±10%) for 3-, 2-, and 1-µg Cr loads, respectively. A baseline was measured every 25 ratios along with a rotation of the amplifiers. A gain calibration was completed at the start of every filament. Instrumental mass fractionation was corrected for using an exponential law and a 50Cr/52Cr ratio of 0.051859 (74). The 54Cr/52Cr ratios are expressed in parts per 10,000 deviation (ε-notation) from the measured NIST SRM 979 standard as ε54Cr.

Titanium isotopic ratios were measured using a Thermo Neptune Plus multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS) at UC Davis. Samples were introduced into the MC-ICPMS using a Nu Instruments DSN-100 desolvating nebulizer. The interface was equipped with a standard H-type skimmer cone and a Jet-style sample cone. Typical intensity for 48Ti was 25 V using a 1011-ohm resistor for a 1-ppm solution run in high-resolution mode. The isotope ratios were measured in a multidynamic routine with 44Ca+, 46Ti+, 47Ti+, 48Ti+, 49Ti+, and 50Ti+ in step 1 and 49Ti+, 51V+, and 53Cr+ in step 2. Ratios were internally normalized to a 49Ti/47Ti ratio of 0.749766 (75). The 50Ti/47Ti ratios are expressed in parts per 10,000 deviation (ε-notation) from the Ti terrestrial standard as ε50Ti.

SIMS O Isotope Analyses.

The O isotopic composition of olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts in chondrules from minimally thermally and aqueously altered meteorites is indistinguishable from that of the glassy mesostasis (e.g., ref. 47). However, glass and plagioclase in chondrules from most unequilibrated chondrites are different from those of olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts due to low-temperature O isotope exchange with 16O-poor fluid (16, 44, 50). Due to extremely slow O isotope diffusion rates of olivine and pyroxene, they preserve the O isotope signature at the time of chondrule formation even in type 4 chondrites (76). Thus, we have analyzed the O isotope ratios of olivine or pyroxene phenocrysts by using secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) in chondrules from Allende (CV3) and Karoonda (CK4) to represent their primary O isotope signatures.

Nineteen chondrules from Allende and Karoonda were remounted into eight 25-mm round epoxy sections with San Carlos olivine standard (SC-Ol, 51) grains for the SIMS O isotope analyses at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. This was done to ensure the best-quality O three-isotope analyses. As many as three chondrules were mounted together in a single epoxy mount. Scanning electron microscope images were obtained for remounted samples using the Hitachi S-3400N at the University of Wisconsin–Madison prior to SIMS analyses. Eight olivine and/or pyroxene grains per chondrule were selected for SIMS analyses. For each grain, semiquantitative energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analyses were acquired (15 keV, 30-s detection time) and applied for matrix corrections during SIMS analyses (discussed below). In the case of BO and PO chondrules, all grains selected were olivine, while a representative selection of both pyroxene and olivine was determined for POP chondrules.

Oxygen three-isotope analyses were performed using the IMS 1280 at the WiscSIMS laboratory under multicollector Faraday cup detections (13–17, 44, 47, 50). The Cs+ primary beam was set to ∼12-µm diameter and 3-nA intensity, which resulted in secondary 16O– intensities of ∼3.5 × 109 counts per second. The contribution of tailing 16O1H– ions on the 17O– signal was negligible (<0.1‰). Each single spot analysis took 7 min, with a typical external precision of ∼0.3‰, ∼0.4‰, and ∼0.4‰ (2 SD) for δ18O, δ17O, and Δ17O (= δ17O – 0.52 × δ18O), respectively. The mass resolving power (MRP at 10% peak height) was set at ∼5,000 for 17O and ∼2,200 for 16O and 18O. Instrumental biases of olivine and pyroxene relative to the SC-Ol standard were calibrated using multiple standards (Fo60, Fo100, En85, En97, and diopside) with known O isotope ratios that cover the range of compositions of the unknowns (50). The results are presented in Datasets S2, S4, and S5.

Mg# of Olivine and Pyroxene in Each Chondrule.

For 10 Allende chondrules selected for coordinated petrology-isotope study, we estimated primary Mg# ([MgO]/[MgO + FeO] molar percent) of olivine and pyroxene using EPMA major element analyses (Dataset S6). The Mg# of olivine and pyroxene reflect the oxidation state of iron (Fe/FeO) and total iron content during chondrule formation (17), which helps us to determine the environment experienced during chondrule formation, such as oxygen fugacity. FeO-poor olivine grains in Allende chondrules sometimes show FeO enrichment toward the grain boundary, which might be caused by Fe–Mg diffusion during the thermal metamorphism on the parent body. Therefore, for chondrules with high Mg# (>95), we compared Mg# of multiple olivine and low-Ca pyroxene analyses from a single chondrule and applied either the maximum Fo contents of olivine or the maximum Mg# of low-Ca pyroxene, whichever was the highest, to be representative Mg# for the chondrule (13, 16).

Oxygen Isotope Mixing Model for Chondrules in a Dust-Enriched System.

A study by ref. 17 constructed a mass balance model to relate O isotope ratios (Δ17O) and Mg# of CR chondrite chondrules that show negative correlation between Δ17O and Mg# as a function of dust-enrichment factor and ratio of H2O ice to anhydrous silicate dust. Here, the modified model by ref. 14 was used to explain Δ17O versus Mg# relationship for chondrules in CV3 (Fig. 5). The model assumes that dust-enriched system consists of solar gas (Δ17O = –28.4‰), anhydrous silicate dust (–8.0‰), organic matters (+11.8‰), and H2O ice (+2.0‰). The model estimates oxygen fugacity relative to iron-wüstite (IW) buffer as a function of system atomic (H/O) and (C/O) ratios for given dust-enrichment factor relative to solar composition and H2O ice enhancement relative to that of CI composition dust (17). The Mg# of mafic silicates are estimated as a function of oxygen fugacity. The Δ17O value is estimated as mass balance of four components with distinct Δ17O values. This model is not applicable to chondrules in ordinary chondrites that do not show a correlation between Mg# and Δ17O (50). If ordinary chondrite-like chondrules formed under the presence of H2O ice, flat Δ17O values against Mg# indicate that H2O ice had Δ17O very similar to those of dust and the Δ17O values would not be sensitive to abundance of H2O ice in the chondrule precursors. For chondrules that formed under dry environments, dust-enrichment factors are estimated from chondrule Mg# using the case with 0 × CI ice enhancement factor in the model. However, if chondrule precursors are depleted in total iron relative to CI abundance, the estimated dust-enrichment factors would be underestimated.

Ti-Cr-O Isotope Mixing Models.

Two-component isotope mixing models in Figs. 3 and 4 were constructed using CAI and noncarbonaceous endmembers. CAIs were assumed to have ε50Ti, ε54Cr, and Δ17O values of 9, 5, and −25, respectively. The ratio of Ti, Cr, and O between CAI and noncarbonaceous endmembers was assumed to be ∼10, ∼0.05, and ∼1, respectively. These isotopic and elemental ratios where held constant and mixing lines were constructed to fit through (or close to) the individual chondrule data by adjusting the ε50Ti, ε54Cr, and Δ17O values of the noncarbonaceous endmember. The ε50Ti and ε54Cr of AOAs was assumed to be similar to CAIs, for example forsterite-bearing CAIs (53). However, these curves are expected to be less hyperbolic than the CAI versus noncarbonaceous endmember mixing curves because the elemental ratios of Ti, Cr, and O between the AOAs and noncarbonaceous endmembers is less extreme (62).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Nehru Cherukupalli (AMNH) for separating chondrules and Brian Hess for SIMS sample preparation. Additional chondrules were provided by the late Ian D. Hutcheon and the University of Alberta. The study was funded by NASA Emerging Worlds Grant NNX16AD34G awarded to Q.-Z.Y., NNX14AF29G to N.T.K. and NNX16AD37G to D.S.E. WiscSIMS is partly supported by NSF (EAR13-55590).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2005235117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the paper, SI Appendix, and Datasets S1–S6.

References

- 1.Krot A. N., Keil K., Scott E. R. D., Goodrich C. A., Weisberg M. K., “Classification of meteorites” in Treatise on Geochemistry, Davis A. M., Ed. (Elsevier, ed. 2, 2014), pp. 83–128. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trinquier A. et al., Origin of nucleosynthetic isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Science 324, 374–376 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin Q.-Z. et al., “53Mn-53Cr systematics of Allende chondrules and ε54Cr-Δ17O correlations in bulk carbonaecous chondrites” in Lunar Planetary Science Conference XL, (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin L., Alexander C. M. O’D., Carlson R. W., Horan M. F., Yokoyama T., Contributors to chromium isotope variation of meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 1122–1145 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren P. H., Stable-isotopic anomalies and the accretionary assemblage of the Earth and Mars: A subordinate role for carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 311, 93–100 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKeegan K. D. et al., The oxygen isotopic composition of the Sun inferred from captured solar wind. Science 332, 1528–1532 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruijer T. S., Kleine T., Borg L. E., The great isotopic dichotomy of the early Solar System. Nat. Astron. 4, 32–40 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruijer T. S., Burkhardt C., Budde G., Kleine T., Age of Jupiter inferred from the distinct genetics and formation times of meteorites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6712–6716 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen M. B., Wielandt D., Schiller M., Van Kooten E. M. M. E., Bizzarro M., Magnesium and 54Cr isotope compositions of carbonaceous chondrite chondrules - Insights into early disk processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 191, 118–138 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Kooten E. M. M. E. et al., Isotopic evidence for primordial molecular cloud material in metal-rich carbonaceous chondrites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2011–2016 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber S., Burkhardt C., Budde G., Metzler K., Kleine T., Mixing and Transport of Dust in the early solar nebula as inferred from titanium isotope variations among chondrules. Astrophys. J. 841, L17 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebert S. et al., Ti isotopic evidence for a non-CAI refractory component in the inner Solar System. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 498, 257–265 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tenner T. J., Kimura M., Kita N. T., Oxygen isotope characteristics of chondrules from the Yamato-82094 ungrouped carbonaceous chondrite: Further evidence for common O-isotope environments sampled among carbonaceous chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 52, 268–294 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hertwig A. T., Defouilloy C., Kita N. T., Formation of chondrules in a moderately high dust enriched disk: Evidence from oxygen isotopes of chondrules from the Kaba CV3 chondrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 224, 116–131 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hertwig A. T., Makoto K., Ushikubo T., Defouilloy C., Kita N. T., The 26Al-26Mg systematics of FeO-rich chondrules from Acfer 094: Two chondrule generations distinct in age and oxygen isotope ratios. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 253, 111–126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertwig A. T., Kimura M., Defouilloy C., Kita N. T., Oxygen isotope systematics of chondrule olivine, pyroxene, and plagioclase in one of the most pristine CV3Red chondrites (Northwest Africa 8613). Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 54, 2666–2685 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenner T. J., Nakashima D., Ushikubo T., Kita N. T., Weisberg M., Oxygen isotope ratios of FeO-poor chondrules in CR3 chondrites: Influences of dust enrichment and H2O during chondrule formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 148, 228–250 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clayton R. N., Mayeda T. K., Goswami J. N., Olsen E. J., Oxygen isotope studies of ordinary chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 2317–2337 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanborn M. E. et al., Carbonaceous achondrites Northwest Africa 6704/6693: Milestones for early Solar System chronology and genealogy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 245, 577–596 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trinquier A., Birck J., Allègre C.-J., Widespread 54Cr heterogeneity in the inner solar system. Astron. J. 655, 1179–1185 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinquier A., Birck J.-L., Allègre C. J., Göpel C., Ulfbeck D., 53Mn-53Cr systematics of the early Solar System revisited. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 5146–5163 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leya I., Schönbächler M., Wiechert U., Krähenbühl U., Halliday A. N., Titanium isotopes and the radial heterogeneity of the solar system. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 266, 233–244 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodrich C. A. et al., Petrogenesis and provenance of ungrouped achondrite Northwest Africa 7325 from petrology, trace elements, oxygen, chromium and titanium isotopes, and mid-IR spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 203, 381–403 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S. et al., Evidence for a multilayered internal structure of the chondritic acapulcoite-lodranite parent asteroid. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 242, 82–101 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herd C. D. K. et al., The Northwest Africa 8159 martian meteorite: Expanding the martian sample suite to the early Amazonian. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 218, 1–26 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunch T. E., Irving A. J., Rumble D. III, Korotev R. L., “Evidence for a carbonaceous chondrite parent body with near-TFL oxygen isotopes from unique metachondrite Northwest Africa 2788” in American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting (2006), pp. P51E–1246.

- 27.Ruzicka A., Grossman J. N., Bouvier A., Herd C. D. K., Agee C. B., The meteoritical bulletin, No. 102. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 1662 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connolly H. C. Jr. et al., The meteoritical bulletin, No. 93, 2008 March. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 43, 571–632 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardner-Vandy K. G. et al., The Tafassasset primitive achondrite: Insights into initial stages of planetary differentiation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 85, 142–159 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irving A. J. et al., Northwest Africa 6704: A unique cumulate permafic achondrite containing sodic feldspar, awaruite, and “fluid” inclusions, with an oxygen isotopic composition in the acapulcoites-lodranite field. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 74, 5231 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton R., Mayeda T., Oxygen isotope studies of carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 2089–2104 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrader D. L. et al., The formation and alteration of the Renazzo-like carbonaceous chondrites I: Implications of bulk-oxygen isotopic composition. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 308–325 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell S. S. et al., The meteoritical bulletin, No. 89, 2005 September. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 40, A201–A263 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clayton R. N., Mayeda T. K., Formation of ureilites by nebular processes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 52, 1313–1318 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clayton R. N., Mayeda T. K., Oxygen isotope studies of achondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 1999–2017 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruzicka A., Grossman J. N., Garvie L., The meteoritical bulletin, No. 100, 2014 June. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 49, E1–E101 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agee C. B. et al., Unique meteorite from early Amazonian Mars: Water-rich basaltic breccia Northwest Africa 7034. Science 339, 780–785 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irving A. J., Bunch T. E., Rumble D. III, Larson T. E., Metachondrites: Recrystallized and/or residual mantle rocks from multiple, large chondritic parent bodies. 68th Annual Meteoritical Society Meeting, 5218 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziegler R. A. et al., Petrology, geochemistry, and likely provenance of unique achondrite Graves Nunataks 06128. Lunar Planetary Science Conference XXXIX, 2456 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tait A. W., Tomkins A. G., Godel B. M., Wilson S. A., Hasalova P., Investigation of the H7 ordinary chondrite, Watson 012: Implications for recognition and classification of Type 7 meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 134, 175–196 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irving A. J. et al., “Collisional distruption of a layered, differentiated CR parent body containing metamorphic and igneous lithologies overlain by a chondritic vaneer” in Lunar Planetary Science Conference XLV, (2014), p. 2465. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown P. G. et al., The fall, recovery, orbit, and composition of the Tagish Lake meteorite: A new type of carbonaceous chondrite. Science 290, 320–325 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grossman J. N., Brearley A. J., The onset of metamorphism in ordinary and carbonaceous chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 40, 87–122 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudraswami N. G., Ushikubo T., Nakashima D., Kita N. T., Oxygen isotope systematics of chondrules in the Allende CV3 chondrite: High precision ion microprobe studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 7596–7611 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clayton R. N. et al., “Oxygen isotopic composition of chondrules in Allende and ordinary chondrites” in Chondrules and Their Origins, King E. A., Ed. (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 1983), pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torrano Z. A. et al., Titanium isotope signatures of calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions from CV and CK chondrites: Implications for early Solar System reservoirs and mixing. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 263, 13–30 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ushikubo T., Kimura M., Kita N. T., Valley J. W., Primordial oxygen isotope reservoirs of the solar nebula recorded in chondrules in Acfer 094 carbonaceous chondrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 90, 242–264 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rubin A. E., Wasson J. T., Clayton R. N., Mayeda T. K., Oxygen isotopes in chondrules and coarse-grained chondrule rims from the Allende meteorite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 96, 247–255 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones R. H. et al., Oxygen isotope heterogeneity in chondrules from the Mokoia CV3 carbonaceous chondrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 3423–3438 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kita N. T. et al., High precision SIMS oxygen three isotope study of chondrules in LL3 chondrites: Role of ambient gas during chondrule formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6610–6635 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ushikubo T., Tenner T. J., Hiyagon H., Kita N. T., A long duration of the 16O-rich reservoir in the solar nebula, as recorded in fine-grained refractory inclusions from the least metamorphosed carbonaceous chondrites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 201, 103–122 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clayton R. N., Onuma N., Grossman L., Mayeda T. K., Distribution of the pre-solar component in Allende and other carbonaceous chondrites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 34, 209–224 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simon J. I. et al., Calcium and titanium isotope fractionation in refractory inclusions: Tracers of condensation and inheritance in the early solar protoplanetary disk. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 472, 277–288 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dauphas N. et al., Neutron-rich chromium isotope anomalies in supernova nanoparticles. Astrophys. J. 720, 1577–1591 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krot A. N., Keil K., Anorthite-rich chondrules in CR and CH carbonaceous chondrites: Genetic link between Ca, Al-rich inclusions and ferromagnesian chondrules. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 37, 91–111 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krot A. N., Hutcheon I. D., Keil K., Anorthite-rich chondrules in the reduced CV chondrites: Evidence for complex formation history and genetic links between CAIs and ferromagnesian chondrules. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 37, 155–182 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krot A. N. et al., Ca,Al-rich inclusions, amoeboid olivine aggregates, and Al-rich chondrules from the unique carbonaceous chondrite Acfer 094: I. Mineralogy and petrology. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 2167–2184 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maruyama S., Yurimoto H., Sueno S., Oxygen isotope evidence regarding the formation of spinel-bearing chondrules. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 169, 165–171 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maruyama S., Yurimoto H., Relationships among O, Mg isotopes and the petrography of two spinel-bearing chondrules. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3943–3957 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Libourel G., Krot A. N., Laurent T., Role of gas-melt interaction during chondrule formation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 251, 232–240 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Libourel G., Portail M., Chondrules as direct thermochemical sensors of solar protoplanetary disk gas. Sci. Adv. 4, r3321 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komatsu M. et al., Mineralogy and petrography of amoeboid olivine aggregates from the reduced CV3 chondrites Efremovka, Leoville and Vigarano: Products of nebular condensation, accretion and annealing. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 629–641 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marrocchi Y. et al., Formation of CV chondrules by recycling of amoeboid olivine aggregate-like precursors. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 247, 121–141 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desch S. J., Kalyaan A., Alexander C. M. O., The effect of Jupiter’s formation on the distribution of refractory elements and inclusions in meteorites. Astrophys. J. 238, 11 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cuzzi J. N., Davis S. S., Dobrovolskis A. R., Blowing in the wind. II. Creation and redistribution of refractory inclusions in a turbulent protoplanetary nebula. Icarus 166, 385–402 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ciesla F. J., Outward transport of high-temperature materials around the midplane of the solar nebula. Science 318, 613–615 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ciesla F. J., The distributions and ages of refractory objects in the solar nebula. Icarus 208, 455–467 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kretke K. A., Lin D. N. C., Grain retention and formation of planetesimals near the Snow line in MRI-driven turbulent protoplanetary disks. Astrophys. J. 664, L55–L58 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bockelée–Morvan D., Gautier D., Hersant F., Huré J.-M., Robert F., Turbulent radial mixing in the solar nebula as the source of crystalline silicates in comets. Astron. Astrophys. 384, 1107–1118 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schrader D. L. et al., Distribution of 26Al in the CR chondrite chondrule-forming region of the protoplanetary disk. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 201, 275–302 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedrich J. M. et al., Chondrule size and related physical properties: A compilation and evaluation of current data across all meteorite groups. Chemie der Erde Geochem. 75, 419–443 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamakawa A., Yamashita K., Makishima A., Nakamura E., Chemical separation and mass spectrometry of Cr, Fe, Ni, Zn, and Cu in terrestrial and extraterrestrial materials using thermal ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 81, 9787–9794 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang J., Dauphas N., Davis A. M., Pourmand A., A new method for MC-ICPMS measurement of titanium isotopic composition: Identification of correlated isotope anomalies in meteorites. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 26, 2197–2205 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shields W. R., Murphy T. J., Catanzaro E. J., Garner E. L., Absolute isotopic abundance ratios and the atomic weight of a reference sample of chromium. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand., A Phys. Chem. 70A, 193–197 (1966). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niederer F., Papanastassiou D., Wasserburg G., Absolute isotopic abundances of Ti in meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 49, 835–851 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 76.McDougal D. et al., Intermineral oxygen three-isotope systematics of silicate minerals in equilibrated ordinary chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 52, 2322–2342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the paper, SI Appendix, and Datasets S1–S6.