Abstract

Background

In spine surgery, surgical site infection (SSI) is one of the main perioperative complications and is associated with a higher patient morbidity and longer patient hospitalization. Most factors associated with SSI are connected with asepsis during the surgical procedure and thus with contamination of implants and instruments used which can be caused by pre- and intraoperative factors. In this systematic review we evaluate the current literature on these causes and discuss possible solutions to avoid implant and instrument contamination.

Methods

A systematic literature search of PubMed addressing implant, instrument and tray contamination in orthopaedic and spinal surgery from 2001 to 2019 was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines. All studies regarding implant and instrument contamination in orthopaedic surgery published in English language were included.

Results

Thirty-five studies were eligible for inclusion and were divided into pre- and intraoperative causes for implant and instrument contamination. Multiple studies showed that reprocessing of medical devices for surgery may be insufficient and lead to surgical site contamination. Regarding intraoperative causes, contamination of gloves and gowns as well as contamination via air are the most striking factors contributing to microbial contamination.

Conclusions

Our systematic literature review shows that multiple factors can lead to instrument or implant contamination. Intraoperative causes of contamination can be avoided by implementing behavior such as changing gloves right before handling an implant and reducing the instruments’ intraoperative exposure to air. In avoidance of preoperative contamination, there still is a lack of convincing evidence for the use of single-use implants in orthopaedic surgery.

Keywords: Implant contamination, Sterilization, Single-use implants, Spinal surgery, Bacteria

Background

In the past few years, the number of spine surgeries performed worldwide has been steadily increasing [1, 2]. One of the main perioperative complications in orthopaedic surgery is surgical site infection (SSI). In spinal surgery, surgical site infection occurs in 2 to 13% and is associated with an increase in patient morbidity, revision surgery, extended hospitalization and health care costs [3, 4]. Factors associated with SSI are the procedures performed, surgical environment and technique, reprocessing procedures of implants and instruments, postoperative measures, and the patients’ immunity. Most of these factors rely on asepsis rather than increasing or decreasing a patient’s immunity [5].

For surgical procedures, the reprocessing of medical products such as surgical instruments or implants by the sterilization processing department is a key process in standard clinical practice and is thought to be essential in the prevention of SSI. As part of this process, surgical instruments and implants are decontaminated, washed, reassembled, labelled, sterilized and redistributed. Since only a small portion of processed implants is used during surgery, these implants are reprocessed multiple times before surgically being implanted in a patient. Even though this is standard clinical practice, little is known about the long-term behavior of reprocessed products especially regarding their contamination. Additionally, despite efforts to reduce the risk of contamination during surgery, correct handling of implants and instruments continues to constitute a challenge and thereby a possible threat to patient safety.

Multiple studies have been conducted on the causes of implant and instrument contamination. Based on their findings, these causes can be divided into two groups: intraoperative contamination for example via air or gloves versus preoperative contamination due to inadequate reprocessing. We conducted this systematic review to evaluate these sources of implant contamination and discuss possible solutions both pre- and intraoperatively to avoid implant and instrument contamination, which in turn leads to higher patient safety during surgery.

Methods

In September 2019 we conducted a systematic literature search of PubMed addressing implant, instrument and tray contamination in orthopaedic and spinal surgery. The systematic review has been reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement [6]. See Table 1 for search terms used. Inclusion criteria comprised studies published in English and studies performed on humans in vivo. Studies in other fields than orthopaedics were excluded as well as studies which did not focus on causes of contamination. Case reports, review articles, technical notes, opinions of experts, and letters to the editors were also excluded. The selected studies’ abstracts were screened and if found inadequate, the full text was evaluated.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Search # | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | Implant or instrument or tray and contamination and orthopedics |

| #2 | Implant or instrument or tray and contamination and spine |

| #3 | Implant or instrument or tray and contaminated and orthopedics |

| #4 | Implant or instrument or tray and contaminated and spine |

| #5 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 |

Results

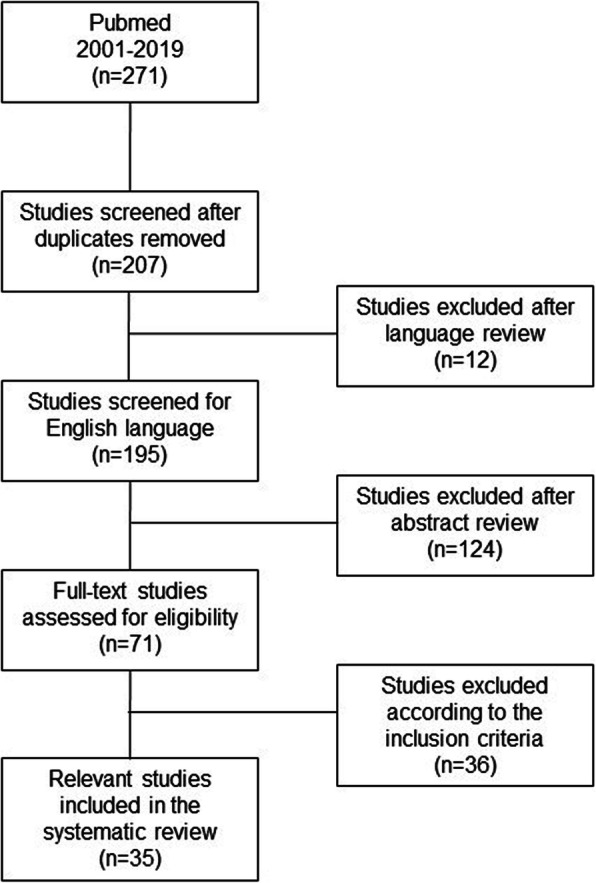

A flow chart of our literature research was created using the PRISMA guidelines (Fig. 1). We identified 271 potential studies via our search strategy. Fifty-four studies were duplicates and thus excluded. Another 12 studies were excluded because they were not written in English. We then excluded 124 studies after reviewing title and abstract. The 71 remaining studies were then assessed for eligibility. Finally, we selected 35 studies for inclusion in our systematic review and divided them into pre- and intraoperative causes of implant and instrument contamination (Tables 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the literature research using the PRISMA guidelines

Table 2.

Included studies on preoperative sources of implant contamination

| Study | Source of contamination | Study size | Main results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative sources of implant contamination | ||||

| Agarwal et al. (2019a) [7] | Pedicle screws |

1. 6 pedicle screws 2. 1 implant tray with 164 pedicel screws |

1. 3 types of contaminants: corrosion, saccharide of unknown origin, soap residue 2. observed reprocessing time was < 2 h |

Repeatedly reprocessed pedicle screws may be source of SSI |

| Pinto et al. (2010) [8] | Surgical implants | 227 samples (76 from clean surgeries, 76 from contaminated surgeries, 75 from infected surgeries) | 47% microbial contamination of implants in clean surgeries, 70% in contaminated, and 80% in infected surgeries | Most of the microorganisms recovered are covered by the cleaning and sterilization process; antibiotic prophylaxis is important in clean surgeries |

| Lopes et al. (2019) [9] | FMRs and DGs | 9 FMRs and 9 DGs (3 rinsing, 3 manual cleaning, 3 manual plus automated cleaning) | 100% ATP contamination in rinsed only with 2–2.5 log10 fold reduction after manual or manual plus automated cleaning; soil present in all groups | Reusable surgical instruments show residual biological soil after reprocessing, which may have an adverse effect on patient outcome |

| Costa et al. (2018) [10] | FMRs, DGs, and single-use screws in clinical use for > 1 year | 73 FMRs (16 ATP, 8 CFU, 40 visual, 9 SEM), 19 DGs (8 ATP, 8 visual, 3 SEM), 123 screws (24 CFU, 90 visual, 9 SEM) |

1. FMRs: 75% showed ATP, 85% visible soil, 63% protein after cleaning 2. DGs: 38% showed ATP, 100% soil after cleaning 3. Screws: Biofilm and soil were visible after cleaning |

Ineffectiveness of manual reprocessing and reprocessing practices threatens patient safety |

| Smith et al. (2018) [11] | Surgical drills | 15 cannulated drill bits (3 per group) | 2 negative controls showed contaminant bacteria; 1 experimental drill showed inoculation bacteria | Standard autoclave sterilization may be inefficient and delay of reprocessing may increase the risk of resistant contamination |

| Mayer et al. (2016) [12] | Femoral BHs | 2 femoral BHs | Complete eradication at all target locations | Adequate decontamination of BHs can be achieved after steam sterilization |

| Bundgaard et al. (2019) [13] | Scissors, knife shafts, puncture cannulae | Not clear | All sterilized instruments showed protein residues below the accepted threshold regardless of holding time | No association between residual protein and holding time |

| Mont et al. (2013) [14] | Saws, cutting guides, trays | 202 patients treated with conventional instruments, 205 patients treated with single-use instruments | Single-use instrumentation led to a significant reduction of compromised pans from 7 to 1%; decrease in contamination in 57% | Single-use instruments will play an increasing role in orthopaedic surgery |

BH broach handle, CFU colony forming unit, DG depth gauge, FMR flexible medullary reamer, SEM scanning electron microscopy

Table 3.

Included studies on intraoperative sources of implant contamination

| Study | Source of contamination | Study size | Main results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative sources of implant contamination | ||||

| Surgical instrument trays | ||||

| Waked et al. (2007) [15] | Surgical instrument trays | 90 sterilization wraps | Detection rates ranged from 7 to 97% | Substantial perforations in sterilization wraps may be missed |

| Mobley and Jackson 3rd. (2018) [16] | Surgical instrument trays | 20 sterilization wraps | Overall 56% accuracy | Current method for assessing sterility is inadequate |

| Surgical equipment | ||||

| Radcliff et al. (2013) [17] | Preoperative in-room time | 7991 spine surgeries including 276 SSIs | ART was significantly higher in patients with infection (68 vs. 61 min); significant increase in infection rate if ART was > 1 h | Preoperative in-room time is a risk factor for SSI |

| Blom et al. (2000) [18] | Surgical drapes | 24 agar plates covered with 7 types of surgical drapes | All of the reusable woven drapes allowed bacterial penetration; non-woven drapes were impermeable apart from one | Recommendation for non-woven disposable drapes over woven drapes |

| Lankester et al. (2002) [19] | Surgical gowns | 40 surgical gowns of 2 types | Disposable gowns showed less bacterial penetration than reusable gowns in all tested regions | Reusable gowns may be unsuitable for use in orthopaedic implant surgery |

| Ward Sr et al. (2014) [20] | Surgical gloves and gowns |

1. 102 surgical team members 2. 251 surgical team members |

1. 31 vs. 7% baseline bacterial contamination in cloth gowns vs. paper gowns 2. 23% of surgeons retaining outer gloves had positive glove contamination vs. 13% of those exchanging gloves |

Recommendation for disposable paper gowns and outer glove exchange just before handling implant materials |

| Klaber et al. (2019) [21] | Surgical gowns | 140 surgical gowns | Bacterial contamination in 12% of surgical gowns (4% in total hip arthroplasty vs. 22% in spine and knee surgery) | Higher surgical gown contamination during non-arthroplasty procedures |

| Wichmann et al. (2019) [22] | Surgical gloves | 43 pairs of knitted cotton outer gloves | 9% of gloves yielded > 100 CFU under aerobic conditions, 14% under anaerobic conditions | Low microbial contamination of knitted cotton outer gloves, but relevant proportion showing contamination above minimal thresholds |

| Amirfeyz et al. (2007) [23] | Theatre shoes | 50 outside shoes, 50 theatre shoes morning and 50 end of day | Microbial growth in 90% of outside shoes, 68% of theatre shows in the morning, and 56% of theatre shoes end-of-day | Recommendation for dedicated theatre shoe use and good floor washing protocol |

| Implant exposure to air | ||||

| Bible et al. (2013) [24] | Coverage of implants | 105 surgical trays (54 uncovered vs. 51 covered trays) | Overall 10% contamination with 2% of covered vs. 17% of uncovered implants | Coverage of implants significantly reduces their contamination |

| Dalstrom et al. (2008) [25] | Coverage of implants | 45 surgical trays (15 uncovered and no traffic, 15 uncovered and traffic, 15 covered) | Microbial growth in 4% at 30 min to 30% at 4 h of uncovered trays vs. 0% in covered trays | Coverage of implants significantly reduces their contamination; microbial growth correlated with the duration of open exposure |

| Menekse et al. (2015) [26] | Coverage of implants | 42 surgical trays (20 uncovered vs. 22 covered) | Microbial growth in 55% vs. 18% in uncovered and covered trays, respectively, after 120 min | Coverage of implants significantly reduces their contamination; microbial growth correlated with the duration of open exposure |

| Uzun et al. (2019) [27] | Coverage of implants | 60 surgical trays (30 uncovered vs. 30 covered) | Statistically significant difference in contamination at all time points | Coverage of implants significantly reduces their contamination; microbial growth correlated with the duration of open exposure |

| Agarwal et al. (2019b) [28] | Usage of an impermeable guard | 10 sterile packaged pedicle screws (5 with and 5 without an intraoperative guard) | All samples without guard showed bacterial growth; none with guard | Using an intraoperative guard provides higher asepsis |

| Smith et al. (2009) [29] | Individual packaging | 50 screw packets | Microbial growth on 48% of packet exteriors and in 14% of acts of opening | Individual packaging of screws is a potential risk factor for contamination |

| Surgical environment | ||||

| Andersson et al. (2012) [30] | Door openings, number of persons in the OR | 30 orthopaedic surgeries in 3 ORs | Positive correlation between CFU and door openings and CFU and number of persons in the OR | Negative impact of traffic flow and number of persons present in the OR |

| Perez et al. (2018) [31] | Door openings, number of persons in the OR | 48 orthopaedic and general surgeries | Positive correlation between CFU and door openings and number of persons in the OR | Negative impact of traffic flow and number of persons present in the OR |

| Knobben et al. (2006) [32] | Door openings, number of persons in the OR, airflow systems | 207 orthopaedic surgeries | Under original conditions 33% of contamination and 11% of SSI, after disciplinary measures and LAF installation 9 and 1% of SSI | Systemic and behavioral changes significantly decrease bacterial contamination and SSI |

| Andersson et al. (2014) [33] | Airflow systems | 63 orthopaedic implant surgeries (30 DV, 33 LAF) | Bacterial growth > 10 CFU/m3 in 1% of LAF ORs and 57% of DV ORs | LAF ORs offer high-quality air during surgery |

| Sadrizadeh et al. (2014) [34] | Airflow systems | Physical model | Reduction of airborne and sedimenting bacteria-carrying particles by MLAF | MLAF may be an option to reduce the level of microbial contamination |

| Sossai et al. (2011) [35] | Airflow systems | 34 total knee arthroplasties (17 with MLAF, 17 without) | Reduction of bacterial count from 24 CFU/m3 without MLAF to 4 CFU/m3 with MLAF | MLAF may be an option to reduce the level of microbial contamination |

| Noguchi et al. (2017) [36] | Airborne particles | 3 patterns of physical movements | Large number of particles when unfolding surgical gown, removing gloves, and putting arms through gown sleeves; LAF reduced particles | Unnecessary actions should be avoided and LAF potentially reduces bacterial contamination |

| Richard and Bowen (2017) [37] | OR surfaces | 13 surfaces in 6 orthopaedic ORs | Bioburden detectable on all included surfaces | Detection of environmental trouble spots in the OR possible with ATP bioluminescence |

| Supportive equipment | ||||

| Ahmad et al. (2011) [38] | Supports | 40 supports used in 20 hip arthroplasty procedures | 85% of anterior and 50% of posterior supports showed bacterial colonisation | High bacterial load on supports may contribute to higher infection rates |

| Ranawat et al. (2004) [39] | Pressure sore prevention pads | 13 pressure sore prevention pads | 85% of pads showed bacterial growth | Use of pressure sore prevention pads should be closely reviewed |

| Ahmed et al. (2009) [40] | Tourniquets | 20 tourniquets | All tourniquets were contaminate with 9 to > 385 CFU | Tourniquets should be cleaned before every surgery |

ART anesthesia ready time, CFU colony forming units, DV displacement ventilation system, LAF laminar airflow ventilation system, MLAF mobile laminar airflow ventilation system, OR operating room, SSI surgical site infection

Preoperative sources of implant contamination

Agarwal et al. recently published a study examining the presence of residual non-microbial contaminants and/or foreign material in pedicle screws after they had been sterilized. Optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy were used in order to identify contaminants on six pedicle screws from four different trays of sterilized implants. In this study, corrosion, saccharides, soap residues and salt residues were found on the examined pedicle screws. According to the authors, finding saccharides was associated with biofilm and the presence of endotoxins. In a second step, the authors analyzed the manufacturer’s guideline regarding the reprocessing recommendations and compared these to their real-time observation of the procedure. Interestingly, the manufacturer recommended at least 19 man-hours for reprocessing of an implant tray with 164 pedicle screws whereas the actually observed reprocessing time was less than 2 hours [7].

Other recent studies also focus on this problem of non-microbial as well as microbial contamination of surgical implants. The importance of reprocessing was emphasized by Pinto et al., who showed in 227 samples that 47% of surgical instruments were contaminated after clean surgery, 70% after contaminated surgery, and 80% after infected surgery [8]. In a smaller study, Lopes et al. investigated the problem of implant contamination after reprocessing by contaminating different reusable surgical instruments with sheep blood and Staphylococcus aureus before repeating different cleaning methods 20 times. Afterwards, they measured adenoside triphosphate (ATP), the microbial load, residual protein as well as soil and biofilm presence and were able to show that independent of the cleaning methods used soil or biofilms were evident on the cleaned surgical instruments [9]. Similar results were shown by Costa et al. who assessed 215 surgical instruments, which had been in clinical use for over a year, for residual ATP, protein, bacterial contamination, endotoxin and biofilm. After sterilization, biofilm and soil were still detectable by electron microscopy [10]. A study by Smith et al. implicated that standard sterilization of cannulated drills may ineffectively sterilize cannulated drills and thus lead to bacterial contamination of these instruments [11]. However, Mayer et al. showed in two femoral broach handles that an adequate decontamination of these instruments can be achieved in both the disassembled and the assembled state [12]. Bundgaard et al. also did not identify protein residues over the threshold even after prolonged holding times of used medical equipment [13]. In knee arthroplasty, it was shown that a decrease in contamination was achieved when using single-use instead of reusable instruments, which in most cases was due to fewer torn wraps in the single-use group [14].

Intraoperative sources of implant contamination

Incorrect or insufficient reprocessing of implants and instruments is not the only source of medical products’ contamination and thereby surgical site infection. The common practice of operating room (OR) personnel evaluating sterile wraps for breaches before using contained instruments is questioned by Waked et al., who found that even bigger wrap defects are missed in 18% [15]. More than 10 years later, Mobley and Jackson showed similar results with an overall accuracy of 56.1%, still suggesting that this practice of assessing sterility is inadequate [16]. Another source of surgical site infection is anesthesia ready time with a significantly higher infection rate in patients with anesthesia ready time longer than 1 hour [17].

However, there have been numerous studies on how to improve intraoperative sterility. Blom et al. showed bacterial penetration in all re-usable woven drapes while disposable drapes were impermeable [18]. Multiple studies recommend the use of disposable paper gowns due to a higher permeability of bacteria and thus a higher contamination rate in reusable gowns [19, 20]. Despite these recommendations, in 2019 Klaber et al. still found a bacterial contamination rate of 12% in 140 surgical gowns in different orthopaedic surgeries, ranging from 4.1% in hip surgery to 21.7% in spine and knee surgery [21].

With operation time the contamination rate of surgical gloves increases significantly, which is why change of surgical gloves before handling implants in order to minimize contamination is recommended [20]. In 43 knitted cotton outer gloves, Wichmann et al. found contamination above the estimated thresholds for implant-associated infection in a relevant proportion of examined gloves [22]. A study by Amirfeyz et al. focused on the contamination of theatre shoes and found significantly higher contamination of outdoor shoes compared to theatre shoes but no difference in samples taken from theatre shoes in the morning versus in the evening. The authors suggest that efficient floor cleaning therefore is important in order to keep shoe contamination levels low [23].

Another source of contamination during surgery is exposure of the used implants and instruments to air. Bible et al. obtained samples from 105 surgical trays at the end of an operation and compared their contamination to that of the paper outer wraps of the trays as well as to samples taken immediately after opening the tray. They were able to show a contamination rate of 2.0% of covered implants versus 16.7% of uncovered implants [24]. Dalstrom et al. did a comparable study in which they examined the contamination of 45 surgical trays at different time points after opening. Here, they were able to show that culture positivity directly correlated with the time the trays were openly exposed. Covering the surgical trays led to a significant reduction in contamination rates [25–27]. Using a guard in order to shield screws and other implants intraoperatively led to a reduction in bioburden compared to unguarded screws as shown by Agarwal et al. in 10 sterile packaged pedicle screws in 2019 [28]. Simply individually packaging screws might in fact lead to infection as suggested by Smith et al. who showed that in seven out of 50 cases, opening these screw-packets over a draped instrument table yielded bacterial growth. This however was not statistically significant [29].

Multiple studies have shown that optimizing the surgical environment leads to a reduced risk of surgical site infections. Positive correlations was found between the total colony-forming units (CFU) per operation and total traffic flow per operation, the number of persons present in the operating room, and the number of door openings [30, 31]. Additionally, in 207 surgeries Knobben et al. also showed that a number of disciplinary measures and the installation of a new laminar flow system lead to a decrease of instrument contamination from over 32.9 to 8.6% and a decrease in superficial surgical site infections from 11.4 to 1.4% [32]. The importance of air flow was also emphasized by other studies, which showed that laminar air flow or mobile laminar airflow units are able to reduce bacterial-carrying particles downstream of the surgical team and the mean bacterial count in the surgical wound [33–36].

Using ATP bioluminecence technology, Richard and Bowen found bioburden in 13 different operating room surfaces, including the OR preparation table and Bovie machine buttons. However, they did not correlate these findings with microbiology cultures or clinical infections [37]. Numerous studies have found that surgical tools such as supports used for patient positioning, pressure core prevention pads, and tourniquets were contaminated mostly with coagulase-negative staphylococci [38–40].

Discussion

The literature evaluated in this systematic review shows that implant and instrument contamination before or during surgery is a well- and long-known problem, which may cause SSI and thereby lead to higher patient morbidity and longer patient hospitalization. While preoperatively mainly inadequate reprocessing was identified as a cause of implant contamination, intraoperatively, a variety of factors may threaten surgical asepsis. Most importantly, aseptic handling of all implants and instruments needs to be ensured. The abovementioned studies indicate that there is a need for improvement in the intraoperative handling of sterile medical products. Thus, different approaches need to be taken in order to prevent SSI.

As shown by multiple studies, an important factor of implant and instrument contamination is their exposure to air, which is why the duration of this exposure needs to be as short as possible and laminar airflow ventilation systems should be installed [24–27]. Additionally, surgical equipment including gloves and gowns play an important role in bacterial contamination. Several authors recommend the use of disposable gowns over reusable ones as they allow lower bacterial penetration [18–20]. To avoid the introduction of cutaneous bacteria from the patient’s skin into the surgical field, gloves should be changed right before handling implants. In their review on this subject, Agarwal et al. additionally list different techniques such as dipping implants in vancomycin or betadine, direct ultraviolet light exposure or covering implants with drapes, all of which yet need to be further examined regarding their ability to reduce SSI [41]. It is also important to point out that to date there is no convincing evidence regarding the relationship between contaminated implants or instruments and the actual development of SSI. Thus, despite its possibly detrimental effect on patient outcome, the extent of the problem remains unclear.

The included preoperative causes of implant contamination raise the question whether the commonly used process of sterilization is an effective way to decontaminate previously used medical products and to what extent screws, plates and other implantable items can be reprocessed at all. The abovementioned study by Agarwal et al. introduces two problems in the reprocessing procedure: 1) In the clinic, recommended reprocessing guidelines may be difficult to implement, especially considering the hospitals’ budgets. 2) Clinically feasible reprocessing may be insufficient in decontaminating medical products [7].

Due to these concerns regarding proper reprocessing of medical products, in the past few years prepackaged, sterile, single-use implants have become increasingly interesting. Not only does the repeated reprocessing of medical products lead to product contamination but the manufacturers’ guidelines often are impractical in the clinic. Thus, the reprocessing of certain medical implants has been banned in some countries such as Scotland and Japan and has been replaced by the use of disposable instruments [42].

However, many of the studies performed in this field are directly sponsored by the industry [43] or conducted by authors with conflicting interests [7]. Only a few small unbiased studies regarding the use of single-use instruments exist. In one of them, Litrico et al. showed in a prospective bi-centric study that the use of single-use surgical instruments in short instrumented spinal fusion surgery led to a reduction of SSI from 6% with reusable instrumentation to 2% with single-use instrumentation. At the same time, clinical outcomes were similar. The authors therefore concluded that wrapping screws and rods in sterile packs until insertion into the patient reduces infection rates by a reduction of exposure and of repetitive hospital sterilization [44].

As there still is a lack of larger studies and meta-analyses, so far no convincing evidence exists regarding the benefit of single-use instruments in orthopaedic surgery. Reprocessing of medical devices is, however, associated with risks and problems, which surgeons need to be aware of in order to guarantee patient safety. Here, more detailed and realizable instructions need to be provided by every manufacturer and training of reprocessing personnel needs to be improved. Most importantly however, ensuring a safe condition of the products used in surgery is not simply the manufacturers’ or the sterilization processing departments’ duty but also one of the personnel in the operating room.

While implant and instrument contamination plays a crucial role in the development of SSI, other risk factors need to be kept in mind to best prevent SSI. In spine surgery, these include not only patient-related factors such as age, comorbidities, smoking, or obesity but also surgery-related factors such as surgical approach, operation time, and blood loss [45–47]. To reduce SSI, the avoidance of implant and instrument contamination therefore needs to be accompanied by a multitude of strategies. As recommended by Anderson et al., patient selection and optimization prior to hospitalization including glycemic control and smoking cessation, perioperative antibiotics, skin antisepsis, and postoperative optimization of patient and wound care need to be implemented [48].

Conclusion

The studies evaluated in this review provide evidence for multiple pre- and intraoperative causes for implant and instrument contamination. However, there have only been few studies on the relationship between contaminated implants or instruments and the actual development of SSI. Thus, the extent of the problem needs to be further investigated in order to provide specific solutions. Knowing of the frequency of contaminations and thereby the possibility of infections, more attention should be drawn to the condition of implants and instruments and known strategies should be implemented in daily clinical practice.

At the same time, the extension of single-use implants and instruments needs to be further studied. As shown by this review, errors in reprocessing are not the only causes of implant contamination and therefore it still needs to be shown that single-use implants actually lead to fewer postoperative infections. Thus, critical analyses not sponsored by the industry regarding the reduction of surgical site infection and regarding cost development are still needed before an unbiased recommendation for the use of these products can be given.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ART

Anesthesia ready time

- ATP

Adenoside triphosphate

- CFU

Colony-forming units

- DG

Depth gauge

- DV

Displacement ventilation

- FMR

Flexible medullary reamer

- LAF

Laminar airflow ventilation system

- MLAF

Mobile laminar airflow ventilation system

- OR

Operating room

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- SSI

Surgical site infection

Authors’ contributions

FS and RA performed the literature search. FS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CP, MP and RA revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Friederike Schömig, Email: friederike.schoemig@charite.de.

Carsten Perka, Email: carsten.perka@charite.de.

Matthias Pumberger, Email: matthias.pumberger@charite.de.

Rudolf Ascherl, Email: rudolf.ascherl@t-online.de.

References

- 1.Pumberger M, Chiu YL, Ma Y, Girardi FP, Mazumdar M, Memtsoudis SG. National in-hospital morbidity and mortality trends after lumbar fusion surgery between 1998 and 2008. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94(3):359–364. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B3.27825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sivasubramaniam V, Patel HC, Ozdemir BA, Papadopoulos MC. Trends in hospital admissions and surgical procedures for degenerative lumbar spine disease in England: a 15-year time-series study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009011. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClelland S, 3rd, Takemoto RC, Lonner BS, Andres TM, Park JJ, Ricart-Hoffiz PA, Bendo JA, Goldstein JA, Spivak JM, Errico T. Analysis of postoperative thoracolumbar spine infections in a prospective randomized controlled trial using the centers for disease control surgical site infection criteria. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:14. doi: 10.14444/3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasliwal MK, Tan LA, Traynelis VC. Infection with spinal instrumentation: review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4(Suppl 5):S392–S403. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.120783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal A, Schultz C, Goel VK, Agarwal AK, Anand N, Garfin SR, Wang JC. Implant prophylaxis: the next best practice toward asepsis in spine surgery. Global Spine J. 2018;8(7):761–765. doi: 10.1177/2192568218762380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ionnidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal A, Schultz C, Agarwal AK, Wand JC, Garfin SR, Anand N. Harboring contaminant in repeatedly reprocessed pedicle screws. Global Spine J. 2019;9(2):173–178. doi: 10.1177/2192568218784298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto FM, de Souza RQ, da Silva CB, Mimica LM, Graziano KU. Analysis of the microbial load in instruments used in orthopedic surgeries. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(3):229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes LKO, Costa DM, Tipple AFV, Watanabe E, Castillo RB, Hu H, Deva AK, Vickery K. Complex design of surgical instruments as barrier for cleaning effectiveness, favouring biofilm formation. J Hosp Infect. 2019;193(1):e53–e60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa DM, Lopes LKO, Vickery K, Watanabe E, Vasconcelos LSNOL, de Paula MC, Melo DS, Hu H, Deva AK, Tipple AFV. Reprocessing safety issues associated with complex-design orthopaedic loaned surgical instruments and implants. Injury. 2018;49(11):2005–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith K, Araoye I, Gilbert S, Waites K, Camins B, Conklin M, Ponce B. Is retained bone debris in cannulated orthopedic instruments sterile after autoclaving? Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(9):1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer RR, Bederman SS, Colin VM, Berger MM, Cesario TC, Schwarzkopf R. Risk of contamination in assembled vs disassembled instruments in hip arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplast. 2016;31(8):1746–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bundgaard K, Sorensen EE, Ripadal K, Christensen AE, Schonheyder HC. Challenging the six-hour recommendation for reprocessing sterilizable medical equipment. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mont MA, Johnson AJ, Issa K, Pivec R, Blasser KE, McQueen D, Puri L, Dethmers DA, Miller DW, Ireland PH, Shurman JR, Bonutti P. Single-use instrumentation, cutting blocks, and trials decrease contamination during total knee arthroplasty: a prospective comparison of navigated and nonnavigated cases. J Knee Surg. 2013;26(4):285–290. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waked WR, Simpson AK, Miller CP, Magit DP, Grauer JN. Sterilization wrap inspections do not adequately evaluate instrument sterility. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:207–211. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318065b0bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mobley KS, Jackson JB., 3rd A prospective analysis of clinical detection of defective wrapping by operating room staff. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(7):837–839. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radcliff KE, Rasouli MR, Neusner A, Kepler CK, Albert TJ, Rihn JA, Hilibrand AS, Vaccaro AR. Preoperative delay of more than 1 hour increases the risk of surgical site infection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(15):1318–1323. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828f1f0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blom A, Estela C, Bowker K, MacGowan A, Hardy JR. The passage of bacteria through surgical drapes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(6):405–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lankester BJ, Bartlett GE, Garneti N, Blom AW, Bowker KE, Bannister GC. Direct measurement of bacterial penetration through surgical gowns: a new method. J Hosp Infect. 2002;50(4):281–285. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward WG, Sr, Cooper JM, Lippert D, Kablawi RO, Neiberg RH, Sherertz RJ. Glove and gown effects on intraoperative bacterial contamination. Ann Surg. 2014;259(3):591–597. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a6f2d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klaber I, Ruiz P, Schweitzer D, Lira MJ, Botello E, Wozniak A. Contamination rate of the surgical gowns during hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139(7):1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00402-019-03211-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wichmann T, Moriarty TF, Keller I, Pfister S, Deggim-Messmer V, Gautier E, Kalberer F, Koch PP, Wahl P. Prevelance and quantification of contamination of knitted cotton outer gloves during hip and knee arthroplasty surgery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139(4):451–459. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-3061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amirfeyz R, Tasker A, Ali S, Bowker K, Blom A. Theatre shoes – a link in the common pathway of postoperative wound infection? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(6):605–608. doi: 10.1308/003588407X205440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bible JE, O’Neill KR, Crosby CG, Schoenecker JG, McGirt MJ, Devin CJ. Implant contamination during spine surgery. Spine J. 2013;13:637–640. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalstrom DJ, Venkatarayappa I, Manternach AL, Palcic MS, Heyse BA, Prayson MJ. Time-dependent contamination of opened sterile operating-room trays. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):1022–1025. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menekse G, Kuscu F, Suntur BM, Gezercan Y, Ates T, Ozsoy KM, Okten AI. Evaluation of the time-dependent contamination of spinal implants: prospective randomized trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40(16):1247–1251. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uzun E, Misir A, Ozcamdalli M, Kizkapan EE, Cirakli A, Calgin MK. Time-dependent surgical instrument contamination begins earlier in the uncovered table than in the covered table. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019. 10.1007/s00167-019-05607-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Agarwal A, Lin B, Wang JC, Schultz C, Garfin SR, Goel VK, Anand N, Agarwal AK. Efficacy of intraoperative implant prophylaxis in reducing intraoperative microbial contamination. Global Spine J. 2019;9(1):62–66. doi: 10.1177/2192568218780676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith G, Vindenes F, Keijzers G, Rando A. Potential for infection in orthopaedic practice due to individually packaged screws. Injury. 2009;40(2):163–165. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersson AE, Bergh I, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Nilsson K. Traffic flow in the operating room: an explorative and descriptive study on air quality during orthopedic trauma implant surgery. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(8):750–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez P, Holloway J, Ehrenfeld L, Cohen S, Cunningham L, Miley GB, Hollenbeck BL. Door openings in the operaing room are associated with increased environmental contamination. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(8):954–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knobben BA, van Horn JR, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Evaluation of measures to decrease intra-operative bacterial contamination in orthopaedic implant surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson AE, Petzold M, Bergh I, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Nilsson K. Comparison between mixed and laminar airflow systems in operating rooms and the influence of human factors: experiences from a Swedish orthopedic center. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(6):665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadrizadeh S, Tammelin A, Nielsen PV, Holmber S. Does a mobile laminar airflow screen reduce bacterial contamination in the operating room? A numerical study using computational fluid dynamics technique. Patient Saf Surg. 2014;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sossai D, Dagnino G, Sanguineti F, Franchin F. Mobile air flow screen for additional operating room ventilation: reduction of intraoperative bacterial contamination during total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol. 2011;12(4):207–211. doi: 10.1007/s10195-011-0168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noguchi C, Koseki H, Horiuchi H, Yonekura A, Tomita M, Higuchi T, Sunaawa S, Osaki M. Factors contributing to airborne particle dispersal in the operating room. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0275-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard RD, Bowen TR. What orthopaedic operating room surfaces are contaminated with bioburden? A study using the ATP bioluminescence assay. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(7):1819–1824. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5221-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad R, Tham J, Nagvi SGA, Butt U, Dixon J. Supports used for positioning of patients in hip arthroplasty: is there an infection risk? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(2):130–132. doi: 10.1308/003588411X12851639107755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ranawat VS, Dowell JK, Teare EL. Pressure sore prevention pads as an infective source in orthopaedic theatres. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(4):318–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed SMY, Ahmad R, Case R, Spencer RF. A study of microbial colonisation of orthopaedic tourniquets. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91(2):131–134. doi: 10.1308/003588409X359402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal A, Schultz C, Goel VK, Agarwal AK, Anand N, Garfin SR, Wang JC. Implant prophylaxis: the next best practice toward asepsis in spine surgery. Global Spine J. 2018;8(7):761–765. doi: 10.1177/2192568218762380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burns H. Migration to single-use pre-sterilised individually wrapped small orthopaedic implants in NHS Scotland. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Attard A, Tawy GF, Simons M, Riches P, Rowe P, Biant LC. Health costs and efficiencies of patient-specific and single-use instrumentation in total knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8(2):e000493. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litrico S, Recanati G, Gennari A, Maillot C, Saffarini M, Le Huec JC. Single-use instrumentation in posterior lumbar fusion could decrease incidence of surgical site infection: a prospective bi-centric study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s00590-015-1692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meng F, Cao J, Meng X. Risk factors for surgical site infections following spinal surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1862–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pull ter Gunne AF, Mohamed AS, Skolasky RL, van Laarhoven CJ, Cohen DB. The presentation, incidence, etiology, and treatment of surgical site infections after spinal surgery. Spine. 2010;35(13):1323–1328. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bcde61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schimmel JJ, Horsting PP, de Kleuver M, Wonders G, van Limbeek J. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections after spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(10):1711–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson PA, Savage JW, Vaccaro AR, et al. Prevention of surgical site infection in spine surgery. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:S114–S123. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.