Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a highly prevalent neurodegenerative disease characterized by Aβ accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation. Epidemiological evidence for a negative correlation between cancer and AD has led to the proposed use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as dasatinib and masitinib for AD, with reported beneficial effects in the AD brain. The TKI vatalanib inhibits angiogenesis by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). Although changes in VEGF and VEGFR have been documented in AD, the effect of vatalanib on AD pathology has not been investigated. In this study, the effects of vatalanib on tau phosphorylation and Aβ accumulation in 5xFAD mice, a model of AD, were evaluated by immunohistochemistry. Vatalanib administration significantly reduced tau phosphorylation at AT8 and AT100 by increasing p-GSK-3β (Ser9) in 5xFAD mice. In addition, vatalanib reduced the number and area of Aβ plaques in the cortex in 5xFAD mice. Our results suggest that vatalanib has potential as a regulator of AD pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Tau, Amyloid beta, 5xFAD mice, Vatalanib, Vascular endothelial growth factor, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common progressive neurodegenerative disease. The accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the brain is the neuropathological hallmark of AD. Aβ plaques are formed from the accumulation of Aβ produced by sequential cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) via β- and γ-secretase, and NFTs are aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau, which normally functions in microtubule stabilization. Aβ plaque and NFT levels are both discriminators of and contributors to AD progression and are closely correlated with cognitive impairment in AD subjects [1]. Although AD and cancer share aging as a common factor, accumulating epidemiological evidence indicates a negative correlation between cancer and AD. This evidence has led to the proposed repurposing of cancer drugs of various mechanisms of action for the treatment of AD [2]. These cancer drugs include tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as dasatinib, masitinib, and imatinib, which have been shown to have therapeutic effects on the pathogenesis of AD [3–5].

Vatalanib, a small-molecule anticancer drug that inhibits angiogenesis (Fig. 1a), is a broad-spectrum TKI that exerts its effects by occupying the ATP-binding sites of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1–3 (VEGFR1–3), platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα), and c-KIT [6]. VEGF and VEGFR have been implicated in angiogenesis as well as blood–brain-barrier (BBB) permeability and microglial chemotaxis in AD pathology [7–9]. VEGF levels are increased in the peripheral blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and microglia of patients with AD and are correlated with the clinical severity of AD [8, 10, 11], and VEGF and VEGFR expression are also increased in AD animal models [12]. However, the effect of vatalanib on tau phosphorylation and Aβ accumulation in the AD brain has not been studied.

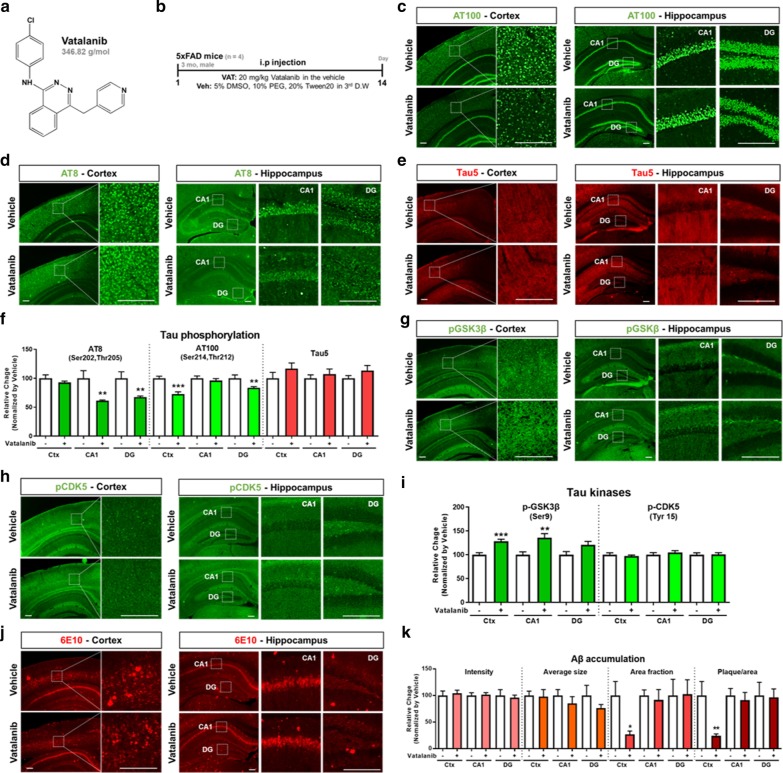

Fig. 1.

Changes in tau phosphorylation and Aβ plaque levels in vatalanib-injected 5xFAD mice. a Molecular structure and weight of vatalanib. b 3-month-old male 5xFAD mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle (Veh) or vatalanib (VAT; 20 mg/kg) daily for 14 days and subsequently sacrificed for histological analysis (see Materials and Methods in Additional file 1). c–f Representative images of immunohistochemical staining with tau phosphorylation-related antibodies in vatalanib-injected 5xFAD mice: anti-AT8 (c), anti-AT100 (d),and anti-Tau-5 (e) (n = 4 mice/group). g–i Representative images of immunohistochemical staining with tau kinase-related antibodies in vatalanib-injected 5xFAD mice: anti-p-GSK-3β (g) and anti-p-CDK5 (h) (n = 4 mice/group). j Representative images of immunohistochemical staining with an anti-6E10 antibody in vatalanib-injected 5xFAD mice. k Quantification of Ab intensity, average size, area fraction, and number of Ab plaques per area from (j) (n = 4 mice/group). All histological quantification results for the vatalanib-treated group (+) were normalized by the vehicle-treated group (−). Scale bar = 200 μm. *p < 0.05; *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle-treated group. N = number of groups

To investigate the effect of vatalanib on the AD brain, we administered 20 mg/kg of vatalanib daily for 14 days to 3-month-old 5xFAD mice, a model of AD (Fig. 1b). Eight hours after the last injection, the mice were fixed via sequential cardiac perfusion with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde, and immunofluorescence staining was performed using AT100 (Ser202 and Thr205), AT8 (Ser214 and Thr212), and Tau5 (total tau) antibodies to visualize tau phosphorylation (Fig. 1c–e). Histological quantification of the fluorescence intensity of tau phosphorylation (Fig. 1f) revealed a significant decrease in AT8 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus (CA1 and DG) of vatalanib-treated 5xFAD mice compared with vehicle-treated 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1c, f). The fluorescence intensity of AT100 was also significantly decreased in the cortex and hippocampus DG of vatalanib-treated 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1d, f). However, the fluorescence intensity of Tau5 was not altered by the administration of vatalanib (Fig. 1e, f). Thus, vatalanib administration in 5xFAD mice significantly reduced phospho-tauSer202, Thr205 and phospho-tauThr212, Ser214 without altering total tau levels.

To investigate the molecular mechanism by which vatalanib modulates tau phosphorylation in 5xFAD mice, immunofluorescence staining was performed with antibodies against p-GSK-3β and p-CDK5, the major molecules involved in tau phosphorylation (Fig. 1g, h). Histological quantification of the fluorescence intensity of tau kinases (Fig. 1i) revealed a significant increase in p-GSK-3βSer9 in the cortex and hippocampus CA1 of vatalanib-administered 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1g, i). However, another major tau kinase, p-CDK5, was not altered by the administration of vatalanib in 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1h, i). It is well known that the constitutive activity of GSK-3β is inhibited by GSK-3β (Ser9) phosphorylation. Therefore, our results suggest that increased phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Ser9) may have contributed to the reduction of tau phosphorylation by vatalanib administration.

To investigate the accumulation of Aβ, another histopathological feature of AD, immunofluorescence staining was performed in vatalanib-treated mice using a 6E10 antibody that labels Aβ1–16 as an epitope (Fig. 1j). To evaluate the effect of vatalanib on Aβ accumulation in 5xFAD mice, the fluorescence intensity, area fraction and average size of Aβ plaques and the number of Aβ plaques per area were quantified based on 6E10 immunoreactivity (Fig. 1k). Although vatalanib administration did not alter the fluorescence intensity of Aβ plaques in 5xFAD mice, the area fraction of Aβ plaques in the cortex was significantly reduced. The number of Aβ plaques per area in the cortex was also significantly reduced in vatalanib-administered 5xFAD mice. However, the average size of Aβ plaques was not altered by vatalanib administration in 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1k).

In summary, we evaluated the effects of vatalanib on AD pathology in 5xFAD mice. Previous studies have demonstrated that both AT8- and AT100-labeled phospho-tau epitopes are elevated in the AD brain [13, 14]. In addition, 5xFAD mice have been reported to exhibit hyperphosphorylation of tau and decreased p-GSK-3β (Ser9) [15]. In the present study, administration of vatalanib attenuated tau phosphorylation at AT8 and AT100 in 5xFAD mice, and these changes were accompanied by increased GSK-3βSer9 phosphorylation (Fig. 1c–i). These results indicate that vatalanib differentially regulates tau phosphorylation by modulating the GSK-3β phosphorylation epitope in 5xFAD mice. While vatalanib administration had no effect on Aβ fluorescence intensity or Aβ plaque size, the number of Aβ plaques excluding intracellular Aβ in the cortex was significantly decreased in 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1k). Considering that 3- to 4-month-old 5xFAD mice predominantly accumulate Aβ in the deep cortical layer and subiculum and not the hippocampus, it is reasonable that vatalanib has an inhibitory effect on Aβ accumulation in the cortex [16]. It is possible that long-term administration of vatalanib might inhibit Aβ accumulation according to age. Interestingly, a recent study found that Aβ oligomers activate microglial cells in a tyrosine kinase-dependent manner [17]. In addition, since VEGF and VEGFR are involved in BBB permeability and microglial chemotaxis, future studies will address whether vatalanib affects neuroinflammatory responses and BBB integrity in 5xFAD mice [7–9]. Moreover, we will evaluate the effects of vatalanib on tauopathy, basal behavior, and cognitive impairment in a mouse model of AD (e.g., PS19 Tau Tg or 5xFAD mice) and identify the mechanism by which vatalanib alters tau phosphorylation as well as synaptic function. In conclusion, intraperitoneal injection of vatalanib in 3-month-old 5xFAD mice reduced Aβ plaque levels and tau phosphorylation, and thus vatalanib may be a drug candidate for Ab-and/or tau-associated diseases, including AD.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.: Materials and methods.

Acknowledgements

Confocal microscopy (Nikon, TI-RCP) data were acquired at the Advanced Neural Imaging Center at the Korea Brain Research Institute (KBRI).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Amyloid β

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- APP

Amyloid precursor protein

- CDK-5

Cyclin-dependent kinase-5

- DG

Dentate gyrus

- GSK-3β

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangle

- PDGFRα

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Authors’ contributions

SGJ and HSH conceived and participated in the design of the study. SGJ, HJL, HP and KMH performed in vivo experiments and histological analysis. SGJ and HSH wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the KBRI basic research program through KBRI funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (Grant numbers 20-BR-02-15, 20-BR-02-20, and 20-BR-03-02) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (Grant number 2019R1A2B5B01070108). This study was partially supported by Whanin Pharm Co., Ltd. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) (Grant number 20190058).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Korea Brain Research Institute (KBRI) (Assigned No. IACUC-2016-0013, IACUC-19-00049, IACUC-19-00042).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13041-020-00673-7.

References

- 1.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanni C, Masi M, Racchi M, Govoni S. Cancer and Alzheimer's disease inverse relationship: an age-associated diverging derailment of shared pathways. Mol Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagalo I, Rusiecka I, Kocic I. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor as a new therapy for ischemic stroke and other neurologic diseases: is there any hope for a better outcome? Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:836–844. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150518235504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhawan G, Combs CK. Inhibition of Src kinase activity attenuates amyloid associated microgliosis in a murine model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflamm. 2012;9:117. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piette F, Belmin J, Vincent H, Schmidt N, Pariel S, Verny M, Marquis C, Mely J, Hugonot-Diener L, Kinet JP, et al. Masitinib as an adjunct therapy for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3:16. doi: 10.1186/alzrt75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood JM, Bold G, Buchdunger E, Cozens R, Ferrari S, Frei J, Hofmann F, Mestan J, Mett H, O'Reilly T, et al. PTK787/ZK 222584, a novel and potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, impairs vascular endothelial growth factor-induced responses and tumor growth after oral administration. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2178–2189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz de Almodovar C, Lambrechts D, Mazzone M, Carmeliet P. Role and therapeutic potential of VEGF in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:607–648. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu JK, Cho T, Choi HB, Wang YT, McLarnon JG. Microglial VEGF receptor response is an integral chemotactic component in Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2888-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange C, Storkebaum E, de Almodovar CR, Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. Vascular endothelial growth factor: a neurovascular target in neurological diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:439–454. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corsi MM, Licastro F, Porcellini E, Dogliotti G, Galliera E, Lamont JL, Innocenzi PJ, Fitzgerald SP. Reduced plasma levels of P-selectin and L-selectin in a pilot study from Alzheimer disease: relationship with neuro-degeneration. Biogerontology. 2011;12:451–454. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SJ, Park MH, Han C, Yoon K, Koh YH. VEGFR2 alteration in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18042-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muche A, Bigl M, Arendt T, Schliebs R. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA, VEGF receptor 2 (Flk-1) mRNA, and of VEGF co-receptor neuropilin (Nrp)-1 mRNA in brain tissue of aging Tg2576 mice by in situ hybridization. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;43:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng-Fischhofer Q, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Illenberger S, Godemann R, Mandelkow E. Sequential phosphorylation of Tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and protein kinase A at Thr212 and Ser214 generates the Alzheimer-specific epitope of antibody AT100 and requires a paired-helical-filament-like conformation. Eur J Biochem. 1998;252:542–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownlees J, Irving NG, Brion JP, Gibb BJ, Wagner U, Woodgett J, Miller CC. Tau phosphorylation in transgenic mice expressing glycogen synthase kinase-3beta transgenes. NeuroReport. 1997;8:3251–3255. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Nishizaki T. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser396 occurs in the much earlier stage than appearance of learning and memory disorders in 5XFAD mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014;274:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, et al. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhawan G, Floden AM, Combs CK. Amyloid-beta oligomers stimulate microglia through a tyrosine kinase dependent mechanism. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2247–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1.: Materials and methods.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.